Abstract

Fault-tolerant quantum computing relies on the ability to detect and correct errors, which in quantum error correction codes is typically achieved by projectively measuring multi-qubit parity operators and by conditioning operations on the observed error syndromes. Here, we experimentally demonstrate the use of an ancillary qubit to repeatedly measure the ZZ and XX parity operators of two data qubits and to thereby project their joint state into the respective parity subspaces. By applying feedback operations conditioned on the outcomes of individual parity measurements, we demonstrate the real-time stabilization of a Bell state with a fidelity of F ≈ 74% in up to 12 cycles of the feedback loop. We also perform the protocol using Pauli frame updating and, in contrast to the case of real-time stabilization, observe a steady decrease in fidelity from cycle to cycle. The ability to stabilize parity over multiple feedback rounds with no further reduction in fidelity provides strong evidence for the feasibility of executing stabilizer codes on timescales much longer than the intrinsic coherence times of the constituent qubits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The inevitable interaction of quantum mechanical systems with their environment renders quantum information vulnerable to decoherence.1,2,3 Quantum error correction aims to overcome this challenge by redundantly encoding logical quantum states into a larger-dimensional Hilbert space and performing repeated measurements to detect and correct for errors.4,5,6,7 For sufficiently small error probabilities of individual operations, logical errors are expected to become increasingly unlikely when scaling up the number of physical qubits per logical qubit.8,9 As the concept of quantum error correction provides a clear path toward fault tolerant quantum computing,10 it has been explored in a variety of physical systems ranging from nuclear magnetic resonance,11 to trapped ions12,13,14,15 and superconducting circuits, both for conventional16,17,18,19 and for continuous variable-based encoding schemes.20

Quantum error correction typically relies on the measurement of a set of commuting multi-qubit parity operators, which ideally project the state of the data qubits onto a subspace of their Hilbert space—known as the code space—without extracting information about the logical qubit state.7 A change in the outcome of repeated parity measurements signals the occurrence of an error, which brings the state of the qubits out of the code space. Such errors can either be corrected for in real-time by applying conditional feedback, or by keeping track of the measurement outcomes in a classical register to reconstruct the quantum-state evolution in post processing. The latter approach—also known as Pauli frame updating21—has the advantage of avoiding errors introduced by imperfect feedback and additional decoherence due to feedback latency. Real-time feedback, on the other hand, could be beneficial in the presence of asymmetric relaxation errors, by preferentially mapping the qubits onto low energy states, which are more robust against decay.22 There are also important instances in which knowledge of the measurement results is required in real time to correctly choose subsequent operations, e.g., for the realization of logical non-Clifford gates,7 for measurement-based quantum computing,23,24 and for stabilizing quantum states in cavity systems.20,25 Therefore, parity measurements, conditional feedback, and Pauli frame updating are all important elements for fault-tolerant quantum computing, and are explored very actively.

Parity detection has previously been studied with superconducting circuits both with and without the use of ancillary qubits. Joint dispersive readout26,27 and the quantum interference of microwave signals28,29 were used to deterministically generate Bell states, and their stabilization was achieved by autonomous feedback based on reservoir engineering.17 Moreover, a recent theoretical proposal presented a protocol for direct weight-4 parity detection.30 However, the most common approach for parity detection uses an ancillary qubit onto which the parity of the data qubits is mapped, and then projectively measured by reading out the ancillary state.31 By using two ancillary qubits, the simultaneous measurement of the XX and ZZ parity operators of two data qubits was demonstrated.32 Furthermore, ancilla-based parity detection has enabled the realization of a three-qubit bit flip code,18 a five-qubit repetition code,19 and the measurement of multi-qubit parity operators for three33 and four34 data qubits. Repeated parity detection was also achieved using joint dispersive readout35 and for the cat code.36

In most previous implementations of ancilla-based parity detection, changes in the measured parity were accounted for in post processing rather than actively compensated for using feedback. Conditional feedback, however, was previously used in superconducting circuits to initialize and reset qubit states,37,38 to demonstrate a deterministic quantum teleportation protocol,39 to create and stabilize entanglement conditioned on a joint dispersive readout,27,35 and to extend the lifetime of a qubit-state encoded as a cat state in a superconducting cavity.20

Here, we report on the experimental realization of repeated ancilla-based XX and ZZ parity detection of two superconducting qubits. We perform real-time conditional feedback to stabilize the data qubits in a Bell state and to actively reset the ancillary qubit to the ground state, see Fig. 1. Our results are, thus, closely related to the recent experiments realized in a trapped ion system.40 We note that similar experiments using Pauli frame updating rather than real-time feedback have been performed in parallel with our work.41

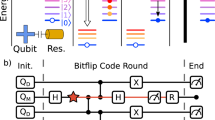

a Joint eigenstates of the parity operators ZZ and XX for the four different combinations of eigenvalues. Mapping to the target state |Φ+〉 is achieved by applying a π-rotation to qubit D2 around the x-axis (z-axis), if ZZ (XX) is measured to be −1. b Gate sequence of the parity stabilization protocol which deterministically projects the qubits onto a unique Bell state. Vertical lines with dots represent conditional phase gates, \(R_y^\theta\) are rotations about the y-axis by an angle θ. Conditional feedback operations are indicated by a double line connected to a measurement operation. The vertical bars indicate a repetition of either the ZZ, or the combined ZZ (1.) and XX (2.) parity detection and feedback

Results

The objective of the protocol is to stabilize two data qubits D1 and D2 in a target Bell state, chosen to be \(|\Phi ^ + \rangle = (|00\rangle + |11\rangle )/\sqrt 2\), for which both the XX and the ZZ parity are even, i.e., take the value +1, see Fig. 1a. We initially prepare both data qubits in an equal superposition state by applying a rotation \(R_y^\theta\) to both qubits with an angle θ = π/2 around the y-axis. We then map the parity of the joint state of D1 and D2 onto the ancillary qubit A by applying two controlled NOT gates—decomposed into conditional phase gates42 and single-qubit rotations—with the ancillary qubit as the target controlled by each of the data qubits. The subsequent measurement of A probabilistically yields the measurement result |0〉 (|1〉) for the ancilla qubit state, indicating the parity operator eigenvalue +1 (−1) and, ideally, projecting the joint state of D1 and D2 into the corresponding even (odd) parity subspace spanned by the basis states |00〉 and |11〉 (|01〉 and |10〉). The probability for each outcome depends on the input state, and is ideally 50% when initializing both qubits in an equal superposition state. After the measurement of A, we map the state of the data qubits into the even parity subspace by flipping the state of D2 with a \(R_x^\pi\) pulse if the parity measurement yields −1.37 In this case, we also reset the ancillary qubit to the ground state in preparation for the next round of parity detection.

Similarly, we perform XX parity measurements by changing the basis of D1 and D2 before and after the parity stabilization sequence with \(R_y^{ \pm \pi /2}\)-pulses, see Fig. 1b. By choosing a feedback protocol that stabilizes both the XX and the ZZ parity to be even, we project the two data qubits onto the unique Bell state \(|\Phi ^ + \rangle = (|00\rangle + |11\rangle )/\sqrt 2\) in two subsequent rounds of parity feedback. Repeating these two parity stabilization steps sequentially ideally stabilizes this Bell state indefinitely. The main requirements for the realization of this protocol are (i) high fidelity and fast readout of the ancillary qubit with little disturbance of the data qubits, (ii) high fidelity single- and two-qubit gates, (iii) low latency classical electronics to perform conditional feedback with delay times much shorter than the qubit coherence times, and (iv) the absence of leakage into non-computational states.

We implement this parity stabilization protocol on a small superconducting quantum processor consisting of a linear array of four transmon qubits, of which each pair of nearest neighbors is coupled via a detuned resonator,43 see Fig. 2. Each qubit has individual charge (pink) and flux control lines (green) to perform single-qubit gates and to tune the qubit transition frequency. Each of the four qubits is coupled to an individual readout circuit used for probing the state of the qubits by frequency multiplexed dispersive readout through a common feedline (purple).44 Further details of the device and its fabrication are discussed in the Methods section. We mount this four-qubit device at the base plate of a cryogenic measurement setup, equipped with input and output lines, specified in Supplementary Note 2, for microwave control and detection.

False-colored micrograph of the four-qubit device used in this work, with transmon qubits shown in yellow, coupling resonators in cyan, flux lines for single-qubit tuning in green, charge lines for single-qubit manipulation in pink, a common feedline for readout in purple, and transmission line resonators for readout and for Purcell filtering in red and blue, respectively

For our experiments, we use the three qubits labeled D1, A, and D2 in Fig. 2. We perform single-qubit gates in 50 ns using DRAG pulses45 with an average gate error of 0.3% characterized by randomized benchmarking.46 The average error remains below 0.38% for all qubits when characterized by simultaneous randomized benchmarking,47 which indicates small crosstalk of the single-qubit gates. Single-qubit gate fidelities are mostly limited by the coherence times, which range from 14 to 23 μs (15 to 22 μs) for T1 (\(T_2^{\mathrm{E}}\)), see Supplementary Table 1. Conditional phase gates are realized with flux pulses on the data qubits in ~180 ns, by tuning the |11〉 state into resonance with the |20〉 state for a full period of the resonant exchange interaction,42 see also Supplementary Note 2. By calibrating and correcting for flux pulse distortion, we achieve two-qubit gate fidelities of 98.8% (99.4%) for the gate between D1 and A (D2 and A) characterized using quantum process tomography,48 while the gate fidelity limit due to decoherence is calculated to be 99.2% (99.5%). The dynamical phases acquired during the flux pulses are compensated using virtual-Z gates.49 Using a readout pulse length of 200 ns and an integration time of 400 ns, see the Methods section, we achieve an average probability for correct readout assignment close to 99% when reading out all three qubits simultaneously.

We characterize the coherent part of the parity detection algorithm by performing quantum-state tomography of all three qubits prior to the first readout of A. Accounting for finite readout fidelity, we average this data to obtain the expectation values for all multi-qubit Pauli operators \(\hat P\) (Fig. 3a). The overall three-qubit state fidelity F = 〈ψ|ρ|ψ〉 ≈ 94%, estimated based on the most likely density matrix ρ reconstructed from the measured Pauli sets, is in good agreement with the fidelity of 92.8%, calculated using a master equation simulation accounting for qubit decoherence and residual ZZ coupling (for details, see Supplementary Note 3). The finite XY correlations, which are well reproduced by the numerical simulations, are due to the residual ZZ coupling between the data qubits and the ancillary qubit with rates 110 and 370 kHz for D1 and D2, respectively, which we do not compensate for during the coherent part of the protocol. A reduction of residual ZZ coupling could, e.g., be achieved with alternative coupling schemes featuring larger on–off ratios.50,51,52

Ideal (black frame), simulated (red frame), and measured (blue) expectation values of multi-qubit Pauli operators \(\hat P\) for a the three-qubit state prior to the first ancilla readout in the basis of D1, A, D2, b, c the state of D1 and D2 conditioned on the respective measurement outcome of A, when simultaneously measuring all three qubits, d the unconditional state after the first ZZ parity measurement and conditional feedback, and e after one round of consecutive ZZ and XX parity stabilization. The quoted fidelities are calculated from the most likely density matrix reconstructed based on the measured Pauli sets. Vertical dashed lines separate the single-qubit operators from two-qubit (and three-qubit) correlations

In a next step, we characterize the state of D1 and D2 conditioned on the outcome of the first ancilla measurement using two-qubit state tomography, see Fig. 3b, c. In this experiment, both D1 and D2 are read out simultaneously with A. For both parity measurement outcomes +1 and −1, projecting D1 and D2 into the even and odd parity Bell state |Φ+〉 and |Ψ+〉, respectively, we find the resulting fidelities (93.8% and 92.9%) to be close to the ones obtained by projecting the reconstructed three-qubit state onto the corresponding two-qubit subspaces (95.9% and 93.4%). This level of agreement is consistent with the high readout assignment probability of 98.7% of the ancillary qubit. Most importantly, we find the outcome of the ancilla measurement to correlate very well with the sign of the resulting ZZ correlations of the data qubits, indicating that the parity measurement is highly projective. More specifically, we find 〈ZZ〉 = +0.86 (−0.89) conditioned on having measured A in the ground (excited) state.

To prepare the specific target state \(|\Phi ^ + \rangle = (|00\rangle + |11\rangle )/\sqrt 2\) deterministically, we apply a π-pulse to qubit D2 if the ancilla measurement yields an odd parity −1, compare circuit diagram in Fig. 1b. Alternatively, we could prepare the state \(|\Psi ^ + \rangle = (|10\rangle + |01\rangle )/\sqrt 2\), by changing the condition for feedback, i.e., applying the feedback pulse if the parity is even. The feedback scheme chosen here, maps the odd-parity state characterized in Fig. 3c to the even-parity state in Fig. 3b. Indeed, the resulting unconditional state has a fidelity of 86.7% indicating that we correctly prepare the desired target state, see Fig. 3d. According to the comparison with master equation simulations (see Supplementary Note 3 for details), the reduced fidelity is dominated by qubit decoherence during the delay time of 1 μs between the parity detection and the application of the feedback pulse to D2. We partly mitigate the dephasing and the residual ZZ interaction by applying four dynamical decoupling pulses using the Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) protocol to the data qubits during the feedback delay time, see pulse sequence in Supplementary Note 2. We observe deterministic phase shifts of both data qubits after completion of the ancilla readout, which we attribute to a measurement-induced Stark shift due to the off-resonant driving of coupling resonators by the ancilla readout pulse.53 We compensate for these phase shifts by inserting virtual-Z gates after the ancilla readout. However, we possibly overcorrect this source of error and, thus, observe smaller phase errors (〈XY〉 and 〈YX〉) in the experiment than expected from simulations (Fig. 3d).

We emphasize that the XX and YY correlations, measured after the ZZ parity check (Fig. 3d), are a consequence of the specific initial state (|00〉 + |01〉 + |10〉 + |11〉)/2, which we prepare prior to mapping onto the even ZZ parity subspace. For the more general case of, e.g., a mixed initial state, we observe a nearly vanishing 〈XX〉 correlation of 0.011 after mapping onto the even ZZ subspace, as expected. Creating and stabilizing finite XX [and YY = −(XX)(ZZ)] correlations, therefore requires a consecutive measurement of the commuting XX parity operator and the projection of D1 and D2 into the corresponding subspace. We achieve this by enclosing the ZZ parity stabilization pulse sequence in appropriately chosen basis change rotations, see Fig. 1b. The resulting state has a fidelity of 74.5% compared with the target state |Φ+〉 (Fig. 3e), close to the simulated value of 75.8%. From simulations, we find that the reduction in fidelity relative to the previous round of parity feedback is dominated by the additional dephasing of data qubits during the XX stabilization cycle.

Most importantly, we also demonstrate the repeatability of parity detection and stabilization which is a crucial requirement for quantum error correction. Specifically, we characterize the evolution of the prepared quantum state for up to 12 cycles of ZZ or XX parity stabilization sequences. We first repeatedly measure the ZZ parity and stabilize the state in the even ZZ subspace. In this case, we observe a decrease of the measured Bell-state fidelity to ~50% after N = 12 cycles (green points in Fig. 4a). This experimental observation is in agreement with master equation simulations and due to the decoherence of the initial 〈XX〉 correlations, which are not stabilized by the repeated ZZ parity checks, see green symbols in Fig. 4c. When the ZZ parity stabilization is paired with a subsequent XX parity stabilization, we observe the expected unconditional stabilization of the target Bell state. Already after a single pair of stabilization cycles (N = 2), the Bell-state fidelity reaches a steady-state value of ~74%, which is maintained for all subsequent stabilization cycles. In agreement with simulations, the 〈XX〉 correlations are now stabilized as well and they take higher values than 〈ZZ〉 because we characterize the state only after stabilizing each even N rounds of feedback, i.e., after stabilizing XX.

a Measured (dots and squares) and simulated (solid and dashed lines) |Φ+〉 state fidelity F after N rounds of ZZ parity stabilization (green), and when iterating between ZZ and XX (blue). b, c Measured and simulated expectation values 〈ZZ〉 and 〈XX〉 for the same two experiments in a. d Measured (dots and squares) and simulated (solid and dashed lines) Bell-state fidelity after N rounds of ZZ parity stabilization (brown), and when iterating between ZZ and XX (purple) using Pauli frame updates (PFU) of the data qubits rather than real-time feedback. e, f Measured and simulated expectation values 〈ZZ〉 and 〈XX〉 for the same experiments as in d

To gain further insights into the feedback process, we also perform the experiment using Pauli frame updates (PFU) rather than applying feedback pulses to the data qubits while still using feedback for resetting the ancilla qubit. Here, we keep track of the parity measurements in software, and apply Pauli frame updating to stabilize the target subspaces. The gate sequence is then equivalent to Fig. 1, but feedback is only used for resetting the ancilla qubit after each parity measurement. As the ancilla is reset in every stabilization round, the Pauli frame update is only conditioned on the last two (one) parity measurements when stabilizing both ZZ and XX (only ZZ) as these two (one) measurements completely determine the corresponding Pauli frame. Thus, if the last ZZ (XX) outcome is −1, we apply a \(R_x^\pi\) (\(R_z^\pi\)) rotation to the Pauli operators of the state tomography of D2 before averaging the data and reconstructing the most likely density matrix.

In Fig. 4d, we observe that the initial-state fidelity is slightly above the one of the active stabilization protocol in Fig. 4a; however, the fidelity now decreases when repeating the protocol. In the end, we observe a 10% lower Bell-state fidelity after N = 12 cycles, half of which is expected from simulations. We attribute the decrease in fidelity to the asymmetry of relaxation errors.22 When the data qubits are not actively stabilized in the even subspaces of the parity operators, the ancilla qubit ends up in the |1〉-state more often. Thus, during the feedback delay, there is a higher chance of T1-errors on the ancilla qubit, which will propagate into the next parity measurement cycle. We also expect that the residual ZZ errors, when the ancilla is in the excited state, lead to accumulated phase errors in 〈XX〉 when only stabilizing ZZ, see Fig. 4f. These accumulated errors are observed in the data and are reproduced in the simulations. Beyond the errors predicted by the simulations, we observe an additional decay of the 〈ZZ〉 correlations. While these errors are significantly larger than expected from simulations, they could be explained by additional measurement-induced transitions from the |1〉-state to the second-excited state of the ancilla qubit during readout. A systematic characterization of leakage errors, caused by both measurement-induced mixing54 and two-qubit gates,55 could be an interesting topic for future investigations.41

Discussion

In conclusion, we demonstrated the stabilization of a Bell state by repeated parity detection combined with conditional real-time feedback. More generally, our experiment demonstrates the use of projective stabilizer measurements to establish coherence between multiple qubits. The measurement acts selectively on the ancilla qubit avoiding measurement-induced dephasing of the data qubits by using individual Purcell filters. Our comparison with Pauli frame updating provides evidence for potential advantages of real-time feedback control for quantum error correction by avoiding errors due to relaxation of the ancilla qubits, a topic to be further investigated. From numerical simulations, by excluding decoherence from the simulation, we find that our protocol stabilizes the target state at 94.9% fidelity limited by readout errors and residual ZZ coupling. Thus, the measured steady-state fidelity is mainly limited by decoherence during the feedback delay time of 1 μs, which we expect to further decrease in the future by reducing the latency of feedback electronics38 and the readout duration.56,57,58,59 Our results constitute an important step toward the real-time stabilization of entangled multi-qubit states beyond Bell states using higher-weight parity detection33,34 as required, for example, in quantum error correction codes, such as the Bacon-Shor code60 and the surface code.8,9

Methods

Sample design and fabrication

The device in Fig. 2 of the main text consists of four qubits coupled to each other in a linear chain. All resonators, coupling capacitors, control lines, and qubit islands are fabricated from a 150 nm thin niobium film sputtered onto a high-resistivity intrinsic silicon substrate, which is patterned using photolithography and reactive ion etching. We further add airbridges to the device to establish a well-connected ground plane across the chip. The Josephson junctions of the qubits are fabricated using electron-beam lithography and shadow evaporation of aluminum. As shown in Fig. 5b, the junctions are arranged in a SQUID loop (blue) and contacted to the niobium film (gray and yellow) using an additional bandage of aluminum (red).61,62

False-colored optical micrographs of characteristic elements of the device. a Data qubit D1 (yellow) coupled to its readout resonator (red). The readout resonator is coupled to the feedline (purple) through a Purcell filter (blue). b Close-up of the SQUID (blue) contacted to the ground plane (light gray) and the qubit capacitor (yellow) using aluminum bandages (red). c Input capacitor Cin of the feedline and coupling capacitor Cκ to one of the Purcell filters. d Coupling resonator (cyan) consisting of three segments with indicated impedances

The qubits are connected via a readout resonator and a Purcell filter to a common feedline used for frequency multiplexed readout, see Fig. 5a and ref. 44 for details of this readout architecture. The capacitive coupling elements between the Purcell filters and the feedline, see Fig. 5c, are designed to have a larger minimal feature size of 6 μm, compared with the 3 μm of our standard interdigitated capacitors, making their capacitance, and thus the frequencies and linewidths of the Purcell filters, less sensitive to slight variations in the photolithography process. The qubits are designed to have a charging energy of 270 MHz set by the total capacitance of the qubit island. An asymmetric SQUID reduces their sensitivity to flux noise.63 From a fit to the measured qubit frequencies as a function of magnetic flux bias, we extract a SQUID asymmetry of ~1:8 for all three qubits. To achieve a large mutual inductance of M ≈ 1.6 pH, we place the SQUID close to the shorted end of the flux line.

Qubit–qubit interactions are mediated by transmission line resonators, see Fig. 5d. Since the coupling strength J is proportional to the impedance of the coupling resonator,43,64 we increase the characteristic impedance for segments of the transmission line resonator to Z0 ≈ 80 Ω compared with the standard value of 50 Ω. We achieve this increase in impedance by increasing the separation between center conductor and ground plane, which results in a smaller capacitance per unit length. The center segment is kept at the standard value of 50 Ω to accommodate an airbridge crossing the resonator to connect the ground planes on both sides of the coupler. The resulting qubit–qubit exchange rate is measured to be J10↔01/2π ≈ 3.8(3.4) MHz at the interaction point of the two-qubit gates between qubits D1 (D2) and A. In addition, we characterized the qubit parameters using standard spectroscopy and time-domain measurements, see Supplementary Note 1.

Readout characterization

With the dispersive shifts χ and the resonator linewidths κeff listed in Supplementary Table 1, we measure correct readout assignment probabilities of ~99%, for both individual and multiplexed readout, the agreement of which indicates low readout crosstalk.44 For this readout, we used a 200 ns long, square-shaped readout pulse. Due to the finite response time of the readout resonator, the resulting output signal is ~400 ns long. In order to maximize distinguishability between the states, we use a 400 ns long mode-matched filter for integrating this signal.44 More specifically, we also characterize the multi-qubit-state assignment and find a probability of more than 95% to correctly assign any three-qubit state, see Fig. 6. We also extract the average cross-measurement-induced dephasing rate, \({\bar{\mathrm \Gamma }}_{ij}\), from the loss of contrast in the Ramsey signal of qubit Qi when interleaving a readout pulse on qubit Qj between two Ramsey pulses.44,65 We find that the probability of inducing a phase error on the data qubits due to the ancilla readout pulse is <0.3%, see Fig. 7. We observe, however, that the readout of qubit A induces a deterministic phase shift on qubits D1 and D2 of 33.4° and 33.2°, respectively, which we attribute to measurement-induced Stark shifts from off-resonantly driving the coupling resonators. In the parity stabilization protocol, we compensate for these phase shifts using virtual-Z gates.49

Data availability

The data produced in this work is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gardiner, C. W. & Zoller, P. Quantum Noise: A Handbook of Markovian and Non-Markovian Quantum Stochastic Methods with Applications to Quantum Optics (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004).

Haroche, S. & Raimond, J.-M. Exploring the Quantum: Atoms, Cavities, and Photons, 1st edn (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006).

Schlosshauer, M. Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007).

Shor, P. W. Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory. Phys. Rev. A 52, R2493–R2496 (1995).

Steane, A. Multiple-particle interference and quantum error correction. Proc. R. Soc. A 452, 2551–2577 (1996).

Lidar, D. A. & Brun, T. A. Quantum Error Correction (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2013).

Terhal, B. M. Quantum error correction for quantum memories. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 307–346 (2015).

Raussendorf, R. & Harrington, J. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with high threshold in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 190504 (2007).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M. & Cleland, A. N. Surface codes: towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 86, 032324 (2012).

Gottesman, D. An introduction to quantum error correction and fault-tolerant quantum computation. In Proc. Symposia in Applied Mathematics (ed. Lomonaco, S. J. Jr.), 13–58, (American Mathematical Society, Washington D.C., 2010).

Cory, D. G. et al. Experimental quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 2152–2155 (1998).

Chiaverini, J. et al. Realization of quantum error correction. Nature 432, 602–605 (2004).

Schindler, P. et al. Experimental repetitive quantum error correction. Science 332, 1059–1061 (2011).

Lin, Y. et al. Dissipative production of a maximally entangled steady state of two quantum bits. Nature 504, 415–418 (2013).

Barreiro, J. T. et al. An open-system quantum simulator with trapped ions. Nature 470, 486–491 (2011).

Reed, M. D. et al. Realization of three-qubit quantum error correction with superconducting circuits. Nature 482, 382–385 (2012).

Shankar, S. et al. Autonomously stabilized entanglement between two superconducting quantum bits. Nature 504, 419–422 (2013).

Ristè, D. et al. Detecting bit-flip errors in a logical qubit using stabilizer measurements. Nat. Commun. 6, 6983 (2015).

Kelly, J. et al. State preservation by repetitive error detection in a superconducting quantum circuit. Nature 519, 66 (2015).

Ofek, N. et al. Extending the lifetime of a quantum bit with error correction in superconducting circuits. Nature 536, 441–445 (2016).

Knill, E. Quantum computing with realistically noisy devices. Nature 434, 39–44 (2005).

O’Brien, T. E., Tarasinski, B. & DiCarlo, L. Density-matrix simulation of small surface codes under current and projected experimental noise. npj Quantum Inf. 3, 39 (2017).

Raussendorf, R. & Briegel, H. J. A one-way quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5188–5191 (2001).

Briegel, H. J., Browne, D. E., Dür, W., Raussendorf, R. & Van den Nest, M. Measurement-based quantum computation. Nat. Phys. 5, 19–26 (2009).

Sayrin, C. et al. Real-time quantum feedback prepares and stabilizes photon number states. Nature 477, 73–77 (2011).

Lalumière, K., Gambetta, J. M. & Blais, A. Tunable joint measurements in the dispersive regime of cavity qed. Phys. Rev. A 81, 040301 (2010).

Ristè, D. et al. Deterministic entanglement of superconducting qubits by parity measurement and feedback. Nature 502, 350–354 (2013).

Roch, N. et al. Observation of measurement-induced entanglement and quantum trajectories of remote superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 170501 (2014).

Roy, A., Leghtas, Z., Stone, A. D., Devoret, M. & Mirrahimi, M. Continuous generation and stabilization of mesoscopic field superposition states in a quantum circuit. Phys. Rev. A 91, 013810 (2015).

Royer, B., Puri, S. & Blais, A. Qubit parity measurement by parametric driving in circuit QED. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau1695 (2018).

Saira, O.-P. et al. Entanglement genesis by ancilla-based parity measurement in 2d circuit qed. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 070502 (2014).

Córcoles, A. D. et al. Demonstration of a quantum error detection code using a square lattice of four superconducting qubits. Nat. Commun. 6, 6979 (2015).

Blumoff, J. Z. et al. Implementing and characterizing precise multiqubit measurements. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031041 (2016).

Takita, M. et al. Demonstration of weight-four parity measurements in the surface code architecture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 210505 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Comparing and combining measurement-based and driven-dissipative entanglement stabilization. Phys. Rev. X 6, 011022 (2016).

Sun, L. et al. Tracking photon jumps with repeated quantum non-demolition parity measurements. Nature 511, 444–448 (2014).

Ristè, D., van Leeuwen, J. G., Ku, H.-S., Lehnert, K. W. & DiCarlo, L. Initialization by measurement of a superconducting quantum bit circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 050507 (2012).

Salathé, Y. et al. Low-latency digital signal processing for feedback and feedforward in quantum computing and communication. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 034011 (2018).

Steffen, L. et al. Deterministic quantum teleportation with feed-forward in a solid state system. Nature 500, 319–322 (2013).

Negnevitsky, V. et al. Repeated multi-qubit readout and feedback with a mixed-species trapped-ion register. Nature 563, 527–531 (2018).

Bultink, C. C. et al. Protecting quantum entanglement from qubit errors and leakage via repetitive parity measurements. arXiv preprint arXiv,1905.12731 (2019).

DiCarlo, L. et al. Demonstration of two-qubit algorithms with a superconducting quantum processor. Nature 460, 240–244 (2009).

Majer, J. et al. Coupling superconducting qubits via a cavity bus. Nature 449, 443–447 (2007).

Heinsoo, J. et al. Rapid high-fidelity multiplexed readout of superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 034040 (2018).

Motzoi, F., Gambetta, J. M., Rebentrost, P. & Wilhelm, F. K. Simple pulses for elimination of leakage in weakly nonlinear qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 110501 (2009).

Magesan, E., Gambetta, J. M. & Emerson, J. Scalable and robust randomized benchmarking of quantum processes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 180504 (2011).

Gambetta, J. M. et al. Characterization of addressability by simultaneous randomized benchmarking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 240504 (2012).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000).

McKay, D. C., Wood, C. J., Sheldon, S., Chow, J. M. & Gambetta, J. M. Efficient z gates for quantum computing. Phys. Rev. A 96, 022330 (2017).

McKay, D. C., Naik, R., Reinhold, P., Bishop, L. S. & Schuster, D. I. High-contrast qubit interactions using multimode cavity qed. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 080501 (2015).

Yan, F. et al. Tunable coupling scheme for implementing high-fidelity two-qubit gates. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 054062 (2018).

Zhang, G., Mundada, P. S. & Houck, A. A. Suppression of qubit crosstalk in a tunable coupling superconducting circuit. https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04182 (2018).

Pechal, M. et al. Geometric phase and nonadiabatic effects in an electronic harmonic oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 170401 (2012).

Sank, D. et al. Measurement-induced state transitions in a superconducting qubit: Beyond the rotating wave approximation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 190503 (2016).

Rol, M. A. et al. A fast, low-leakage, high-fidelity two-qubit gate for a programmable superconducting quantum computer. https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.02492 (2019).

McClure, D. T. et al. Rapid driven reset of a qubit readout resonator. Phys. Rev. Appl. 5, 011001 (2016).

Bultink, C. C. et al. Active resonator reset in the nonlinear dispersive regime of circuit QED. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 034008 (2016).

Boutin, S., Andersen, C. K., Venkatraman, J., Ferris, A. J. & Blais, A. Resonator reset in circuit qed by optimal control for large open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. A 96, 042315 (2017).

Walter, T. et al. Rapid, high-fidelity, single-shot dispersive readout of superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 7, 054020 (2017).

Bacon, D. Operator quantum error-correcting subsystems for self-correcting quantum memories. Phys. Rev. A 73, 012340 (2006).

Dunsworth, A. et al. Characterization and reduction of capacitive loss induced by sub-micron josephson junction fabrication in superconducting qubits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 022601 (2017).

Nersisyan, A. et al. Manufacturing low dissipation superconducting quantum processors. https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.08042 (2019).

Hutchings, M. D. et al. Tunable superconducting qubits with flux-independent coherence. Phys. Rev. Appl. 8, 044003 (2017).

Koch, J. et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the Cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A 76, 042319 (2007).

Bultink, C. C. et al. General method for extracting the quantum efficiency of dispersive qubit readout in circuit qed. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 092601 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank A. Blais, B. Royer, J. M. Renes, and J. Home for valuable feedback on the paper and J. Butscher, F. Bruckmaier, and M. Bild for contributions to the experimental setup and the control software. The authors acknowledge financial support by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), via the U.S. Army Research Office grant W911NF-16-1-0071, by the National Centre of Competence in Research Quantum Science and Technology (NCCR QSIT), a research instrument of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the EU Flagship on Quantum Technology H2020-FETFLAG-2018-03 project 820363 OpenSuperQ and by ETH Zurich. The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors, and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of the ODNI, IARPA, or the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.K.A., A.R., S.K., J.H., A.W. and C.E. designed the experiment. C.K.A. designed the device and A.R., S.K., J.-C.B. and M.G. fabricated the device. C.K.A., A.R., S.L., S.K. and J.H. set up the experiment and wrote the experimental control software. C.K.A., A.R. and S.L. carried out the experiment, analyzed all data, and produced all figures. C.K.A. and S.L. performed the numerical simulations. A.W. and C.E. supervised the work. C.K.A., A.W. and C.E. wrote the paper with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andersen, C.K., Remm, A., Lazar, S. et al. Entanglement stabilization using ancilla-based parity detection and real-time feedback in superconducting circuits. npj Quantum Inf 5, 69 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0185-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0185-4

This article is cited by

-

Fast joint parity measurement via collective interactions induced by stimulated emission

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Encoding a magic state with beyond break-even fidelity

Nature (2024)

-

Strong parametric dispersive shifts in a statically decoupled two-qubit cavity QED system

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Realizing a deep reinforcement learning agent for real-time quantum feedback

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Realization of a quantum neural network using repeat-until-success circuits in a superconducting quantum processor

npj Quantum Information (2023)