Abstract

Short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) prescriptions and associated outcomes were assessed in 1440 patients with asthma from the SABA use IN Asthma (SABINA) III study treated in primary care. Data on asthma medications were collected, and multivariable regression models analysed the association of SABA prescriptions with clinical outcomes. Patients (mean age, 47.9 years) were mostly female (68.6%); 58.3% had uncontrolled/partly controlled asthma and 38.8% experienced ≥1 severe exacerbation (reported in 39% of patients with mild asthma). Overall, 44.9% of patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters (over-prescription) and 21.5% purchased SABA over-the-counter. Higher SABA prescriptions (vs 1−2 canisters) were associated with significantly decreased odds of having at least partly controlled asthma (6–9 and 10–12 canisters) and an increased incidence rate of severe exacerbations (10–12 and ≥13 canisters). Findings revealed a high disease burden, even in patients with ‘mild’ asthma, emphasising the need for local primary care guidelines based on international recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common chronic conditions affecting over 300 million people worldwide1,2. Despite the availability of a range of effective treatment options, asthma continues to impose a significant socioeconomic burden on patients and healthcare systems worldwide3. Although healthcare policies and evidence-based treatment recommendations at both national and international levels are available to guide clinical practice, asthma remains uncontrolled in a considerable proportion of patients4,5.

Among all healthcare practitioners (HCPs), primary care physicians (PCPs) represent the first point of contact for most patients with asthma6. Consequently, they play an essential role in the holistic management of asthma7,8 and are uniquely positioned to exert a major influence on asthma care3,6. Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognises that healthcare systems with strong primary care services are crucial to improve treatment outcomes and deliver comprehensive care9. However, the availability of good-quality primary care remains highly variable, with the WHO reporting that the average health spending per person in 2017 was approximately 70 times lower in low income countries (US $41) than in high income countries (US $2937)10. Moreover, results from a systematic review reported that in 18 countries representing approximately 50% of the global population, PCPs spent 5 min or less per consultation with their patients11. In addition, PCPs are often faced with a multitude of challenges, particularly diagnostic uncertainties in patients with mild asthma12,13 or those with normal lung function parameters14. Additionally, implementation of evidence-based recommendations in the primary care setting may be hindered by factors such as non-availability of diagnostic resources in many geographical regions, limited time for in-depth diagnostic assessments, and lack of specific primary care guidelines6,7,15,16.

Inappropriate use of asthma medications17, in the form of excessive use of short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs), possibly combined with underuse of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)16,18,19,20, remains a major challenge in respiratory care, contributing to poor treatment outcomes21. Therefore, following a landmark update in 201922, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) no longer recommends as-needed SABA without concomitant ICS for patients ≥12 years of age3. These updated treatment recommendations largely impact PCPs who represent the frontline of patient management. However, PCPs are often not familiar with GINA23, and there is often a time lag between revised GINA recommendations and updates to local guidelines. This may contribute to clinical practices not being aligned with the latest treatment recommendations, resulting in PCPs prescribing SABAs to patients at the time of asthma diagnosis, thereby delaying the initiation of regular preventer medication24. In addition, most patients with asthma have mild disease and are therefore commonly prescribed SABA-only treatment25. However, all patients, including those with mild asthma, are at risk of exacerbations3, with clinical trial data reporting that patients with mild asthma using as-needed SABA experience a 60% higher rate of moderate-to-severe exacerbations than those receiving ICS-containing treatment26. Therefore, a detailed understanding of SABA prescription practices across asthma severities in primary care, including the potential impact of SABA over-the-counter (OTC) purchase, would be of considerable value, particularly in less well-resourced countries where current data on SABA use are lacking.

To continue to assess the global extent of SABA use and its clinical consequences, the SABA use IN Asthma (SABINA) III (International) study was initiated in 24 countries across 5 continents in 8351 patients treated by both PCPs and specialists. Results reported that more than a third of patients with asthma were over-prescribed SABAs (≥3 canisters) in the 12 months prior to study entry27. Moreover, SABA over-prescription was associated with poor asthma-related health outcomes27. To better understand how asthma is managed globally in the primary care setting, we assessed prescriptions of SABA and other asthma medications (including ICS-containing treatments and oral corticosteroids [OCS]), OTC purchases of SABA, and clinical outcomes associated with SABA prescriptions in the cohort of patients from the SABINA III study who were treated by PCPs.

Results

Study population and patient characteristics

Of the 8351 patients in the SABINA III study, 17.2% (n = 1440) were managed exclusively by PCPs. Patients had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 47.9 (16.73) years (Table 1). The majority of patients were female (68.6%), had a body mass index (BMI) of ≥25 kg/m2 (63.8%), and had never smoked (78.7%). Over one-third of patients (35.5%) reported no healthcare reimbursement.

Disease characteristics

The mean duration of asthma was 17.2 years (Table 2). Investigator-classified mild (GINA treatment steps 1–2) and moderate-to-severe (steps 3–5) asthma was reported in 51.7 and 48.3% of patients, respectively. Overall, 41.2% of patients had no comorbidities, with 41.4% reporting 1–2 comorbidities,. Patients reported a mean (SD) of 1.0 (2.42) severe asthma exacerbation in the 12 months preceding study initiation, with 38.8 and 12.3% of patients experiencing ≥1 and ≥3 severe exacerbations, respectively.

A similar proportion of patients with mild and moderate-to-severe asthma experienced ≥1 (39.0 and 38.4%, respectively) and ≥3 (13.7 and 10.8%, respectively) severe asthma exacerbations in the previous 12 months. The level of asthma symptom control was assessed as well controlled in 41.7%, partly controlled in 34.9%, and uncontrolled in 23.3% of patients.

SABA prescriptions

Overall, 44.9% of patients received prescriptions for ≥3 SABA canisters in the 12 months prior to study entry, and 26.3% received prescriptions for ≥10 SABA canisters; 33.4% of patients were not prescribed any SABA canisters (Fig. 1). Prescription of ≥3 and ≥10 SABA canisters was higher in patients with mild asthma (53.7 and 30.0%, respectively) than in those with moderate-to-severe asthma (35.2 and 22.3%, respectively).

aInvestigator-classified asthma severity was guided by GINA 2017 treatment steps. Investigators were guided by GINA 2017 treatment steps either in the study protocol or via a pop-up window in the eCRF. Missing data: n = 4, mild asthma; n = 31, moderate-to-severe asthma. eCRF electronic case report form, GINA Global Initiative for Asthma, OTC over the counter, PCP primary care physician, SABA short-acting β2-agonist, SABINA SABA use IN Asthma.

Altogether, 12.7% of patients were prescribed SABA monotherapy, all of whom had mild asthma (Table 3). Among these patients, 60.6 and 45.0% were prescribed ≥3 and ≥10 SABA canisters in the 12 months prior to the study visit, respectively (Fig. 2). More than half of all patients (54.7%) were prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance therapy in the previous 12 months (Table 3). Among these patients, 69 and 38.2% were prescribed ≥3 and ≥10 SABA canisters, respectively (Fig. 2). A comparable proportion of patients with mild and moderate-to-severe asthma were prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance therapy (55.5 and 54.7%, respectively). Prescription of ≥3 SABA canisters was also comparable among patients with mild and moderate-severe asthma (71.8 and 65.9%, respectively).

aSABA monotherapy was prescribed only to patients with mild asthma. bInvestigator-classified asthma severity was guided by GINA 2017 treatment steps. Investigators were guided by GINA 2017 treatment steps either in the study protocol or via a pop-up window in the eCRF. Missing data: n = 3, patients with mild asthma prescribed SABA alone; n = 1, patient with mild asthma prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance treatment; n = 31, patients with moderate-to-severe asthma prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance treatment. eCRF electronic case report form, GINA Global Initiative for Asthma, PCP primary care physician, SABA short-acting β2-agonist, SABINA SABA use IN Asthma.

SABA obtained OTC without prescriptions

In those countries where SABA was available OTC without a prescription, 21.5% of patients purchased SABA OTC, of whom 40.5 and 6.5% purchased ≥3 and ≥10 SABA canisters, respectively. Among patients who purchased SABA OTC (n = 309), 57.9% had received SABA prescriptions as well (Supplementary Fig. 1); 72.7% for ≥3 canisters and 39.1% for ≥10 canisters in the previous 12 months.

Prescriptions for asthma medications other than SABA

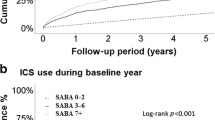

Overall, 31% of patients were prescribed maintenance therapy in the form of ICS, with a mean (SD) of 7.2 (7.0) ICS canisters in the preceding 12 months (Table 4A). An ICS/long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) was prescribed to 49.4% of patients (Table 4B).

In the 12 months prior to study entry, 21.5% of patients were prescribed OCS burst treatment (Table 4C). OCS burst prescriptions were common across all SABA categories and asthma severities, regardless of asthma treatments prescribed in the previous 12 months (Supplementary Fig 2). Overall, across most SABA prescription categories (1–2, 3–5, 6–9, and 10–12 canisters), a higher proportion of patients with mild asthma (ranging from 12 to 17.7%) were prescribed OCS bursts compared with those with moderate-to-severe asthma (ranging from 4.3 to 15.1%).

Association of SABA prescriptions with asthma-related health outcomes

Disposition of patients included in the secondary analysis is shown in Supplementary Fig 3. The pre-specified regression analyses, adjusted for pre-specified covariates and potential confounders, showed that prescription of 10–12 and ≥13 SABA canisters (vs 1–2 canisters) in the previous 12 months was associated with a 49% (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25–1.79; P < 0.0001) and 90% (adjusted IRR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.49–2.41; P < 0.0001) significantly increased incidence rate of severe exacerbations, respectively. Further details are provided in Fig. 3.

Note: ORs were adjusted for age, country, sex, and smoking as pre-specified covariates; and GINA step by investigator, healthcare insurance, education level, comorbidities, duration of asthma, and BMI as potential confounders. IRRs were adjusted for age, country, sex, and smoking as pre-specified covariates; and duration of asthma and BMI as potential confounders. BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, GINA Global Initiative for Asthma, IRR incidence rate ratio, OR odds ratio, PCP primary care physician, SABA short-acting β2-agonist, SABINA SABA use IN Asthma.

Compared with prescription of 1–2 SABA canisters, prescription of 6–9 and 10–12 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months was associated with a 47% (odds ratio [OR], 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31–0.89; P = 0.016) and 57% (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.26–0.71; P = 0.001) significantly lower odds of having at least partly controlled asthma (partly controlled plus well-controlled asthma), respectively. Further details are provided in Fig. 3.

Key differences between the SABINA III PCP cohort and the overall SABINA III population

Data were generally consistent between the two populations, although there were a few exceptions (Supplementary Table 1). Compared with the overall SABINA III population, the PCP cohort had more patients with no healthcare reimbursement (35.5% vs 27.3%). Moreover, fewer patients treated by PCPs, compared with the overall SABINA III population, had ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation (38.8% vs 45.4%). In contrast to the high proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma in the overall SABINA III population (76.5%)27, the PCP cohort had a more balanced distribution (mild asthma, 51.7%; moderate-to-severe asthma, 48.3%).

Of those patients prescribed SABA monotherapy, a higher proportion in the PCP cohort compared with the overall SABINA III population27 were prescribed ≥3 (60.6% vs 53.6%) and ≥10 (45.0% vs 29.9%) SABA canisters in the 12 months prior to study entry. Although prescriptions for SABA in addition to maintenance therapy were comparable between the PCP cohort and overall SABINA III population (54.7% vs 58.0%, respectively)27, a higher proportion of patients treated in primary care were prescribed ≥3 (69% vs 61.7%) and ≥10 (38.2% vs 29.3%) SABA canisters.

Discussion

This large cross-sectional study in 24 countries provides valuable real-world insights into the management of asthma in primary care at a global scale. Although most patients were prescribed maintenance therapy in the form of ICS or ICS/LABA fixed-dose combination, SABA over-prescription was common, even in patients with mild asthma. Approximately half (44.9%) of all patients were prescribed SABA in excess of current treatment recommendations (≥3 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months), which was associated with poor asthma-related health outcomes, both in terms of increased incidence of severe exacerbations and poor asthma control.

In line with previous studies19,20, SABA over-prescription in primary care was high, with a greater proportion of patients in the PCP cohort being prescribed ≥3 and ≥10 SABA canisters (both as monotherapy and in addition to maintenance therapy) compared with the overall SABINA III population27. Notably, SABA over-prescription was more common in patients with mild asthma, suggesting potential under-estimation of asthma severity in patients with milder disease or the inappropriate management of patients with ‘mild’ asthma, resulting in poor symptom control.

Additionally, OTC purchase of SABA was common in primary care, with 21.5% of patients purchasing SABA OTC without a prescription in the preceding 12 months. Among patients with both SABA OTC purchase and prescriptions, most had already been prescribed ≥3 (72.7%) and ≥10 (39.1%) canisters, a trend that was more apparent in patients with mild than moderate-to-severe asthma (24.1% vs 18.4%). Since SABA OTC purchase has been associated with under-treatment of asthma28, healthcare policy makers and national governments should collaborate effectively to improve access to affordable care and regulate SABA OTC purchase to ensure optimal asthma care.

The prescription of OCS bursts was common across all SABA prescription categories and asthma severities, especially in patients prescribed 1–2 SABA canisters and those with mild asthma. SABA overuse and high exposure to OCS have been associated with insufficient prescription of maintenance therapy29, whilst increasing OCS prescriptions (≥4 per year) is associated with deleterious adverse events regardless of dose, duration, or continuous sporadic use30. Hence, there is an urgent need to reduce inappropriate prescribing of both SABA and OCS and to accurately document prescriptions, dispensing and use of OCS for worsening asthma symptoms, and managing exacerbations. To this end, in those countries with adequate healthcare services and where physicians have sufficient time to engage in behaviour change counselling, PCPs could provide patients with self-management training to help them recognise symptom worsening and provide instructions on appropriate use of reliever and maintenance medication, as well as OCS3.

Findings from this PCP cohort revealed that higher SABA prescriptions were, with a few exceptions, significantly associated with an increase in the rate of severe exacerbations (10–12 and ≥13 canisters) and lower odds of achieving at least partly controlled asthma (6–9 and 10–12 canisters). Although results from the overall SABINA III study showed a statistically significant association between increasing SABA prescriptions and poor asthma-related outcomes across all SABA categories27, this was not observed in this PCP cohort, likely due to the smaller patient population. However, findings from a larger cohort of patients (>570,000) in the United Kingdom (UK) who were treated in primary care (SABINA I)18 were consistent with those reported in SABINA III. Nonetheless, SABA prescription patterns in the PCP cohort were in line with the overall SABINA III population, highlighting the importance of monitoring both SABA prescriptions and SABA use to identify patients at increased risk of exacerbations, especially those under-prescribed ICS. Indeed, over-prescription of SABAs and insufficient provision of ICS-containing treatments have been identified as preventable causes of death from asthma16. Following the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) in the UK, the Royal College of Physicians (London) in its report titled ‘Why asthma still kills’ recommends that PCPs have an oversight of the patient’s entire prescription history so that SABA over-prescription can be closely monitored31.

Most patients treated in primary care were prescribed maintenance medication, either ICS or fixed-dose combinations of ICS/LABA. However, patients were prescribed a mean of 7.2 canisters of ICS in the previous 12 months. This quantity suggests potential under-prescription on the basis that one canister per month is considered good clinical practice3, and most patients were not prescribed multiple maintenance treatments, although in some cases, single ICS inhalers provide a ≥2-month supply. In addition, the majority of patients with mild asthma were prescribed ICS at a medium dose (57.6%) instead of the recommended low dose3. Taken together, these findings demonstrate the need for better alignment of both reliever and maintenance medication prescription practices with GINA recommendations by adapting asthma management guidelines to the primary care setting. Most currently available guidelines are complex, long, and generally biased towards a secondary care perspective7, which may limit their utility and has led the GINA committee to acknowledge the difficulty in implementing their recommendations in primary care3; therefore, their adaptation for PCPs to ensure wider acceptance22,32 would be of considerable value.

Consistent with earlier studies33,34,35,36, the level of asthma control in patients treated by PCPs was poor, suggesting that identification of patients with suboptimal asthma control remains a challenge in primary care. Our findings revealed that 57.2% of patients with mild disease reported having uncontrolled/partly controlled asthma, potentially due to inadequate treatment, and suggestive of under-recognition of both disease control and underlying asthma severity. Indeed, both PCPs33,37,38 and patients5 tend to overestimate the level of asthma control, leading to under-treatment of the disease37. Moreover, patients often perceive control as symptom relief and/or management of exacerbations, reflective of crisis-oriented disease management39, which may further contribute to SABA over-reliance. This could also account for the high SABA OTC purchase observed in this cohort of patients treated by PCPs, particularly in those with mild asthma. Consequently, use of objective and validated tools, such as the Asthma Control Test (ACT) and the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)3, can assist PCPs in promptly identifying patients who may require a more detailed assessment, thereby addressing the discrepancy between perceived and actual disease control.

Poor asthma control translated into a high disease burden in this PCP cohort, with more than a third of patients (38.8%) experiencing ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation in the preceding 12 months. Moreover, 39.0 and 13.7% of patients with mild asthma experienced ≥1 and ≥3 severe asthma exacerbations, respectively. SABA over-prescription is a modifiable risk factor for exacerbations40, with results from a SABINA study conducted in the UK reporting that SABA over-prescription was associated with a 20% increased rate of exacerbations in patients with mild asthma, even after adjusting for various confounding factors18. Another possible explanation for this high disease burden is that healthcare reimbursement was not available to a substantial proportion of patients overall (35.5%), including a higher proportion of patients with mild than with moderate-to-severe asthma (43.1% vs 27.5%). Inadequate healthcare insurance coverage and limited access to healthcare continue to be major barriers in accessing cost-effective treatments in many of the countries included in this study1,41 and have been associated with a reduced use of regular preventive care, increased use of emergency care42, and consistently poorer quality of asthma care, including a lower likelihood of receiving ICS43. Furthermore, the high cost of maintenance medication, such as ICS/LABA combination inhalers, can limit its use, especially in low- and middle-income countries where access to affordable medicines represents an unmet need1,41.

Overall, our findings reveal that PCPs need to reconsider approaches for managing asthma effectively, particularly in relation to the regular monitoring of both asthma control and SABA prescriptions/use to identify patients at risk of poor health outcomes. Importantly, PCPs need to ensure an accurate evaluation of underlying asthma severity so that appropriate treatment may be initiated or maintained through a step-wise process.

Since many patients with mild asthma remain uncontrolled, frequently have poor treatment adherence and often underestimate the seriousness of their condition, some PCPs could play a role in establishing asthma action plans25, discussing treatment-related issues, providing educational support and, if available, referring patients to HCPs trained in asthma education3. Although patients recognise early signs of asthma worsening, their initial response is frequently to increase SABA rather than ICS intake. Therefore, symptom-based use of a fast-acting β2-agonist and ICS combination as the default reliever option44, which relies on patients’ inherent symptom relief–seeking behaviour45 and is supported by GINA3, offers a viable asthma management strategy to overcome poor adherence since these medications are available in most primary care and low-income settings44.

Dispensing/prescription of excess SABA inhalers should be identified as a sign of poorly controlled asthma31. Therefore, putting practice systems in place whereby PCPs receive notifications from pharmacies for SABA inhalers supplied without a prescription would serve as a useful reminder to proactively review asthma control31. Since PCP consultation times can adversely affect patient care11, approaches such as arranging appointments so that they do not occur simultaneously, organising regular reviews in advance, and improving the system for scheduling walk-in patients could further optimise efficiency in the primary care setting46.

Since poor asthma-related health outcomes in primary care have been attributed to gaps between evidence-based recommendations and clinical practice33,47, further improvements may be achieved by increasing awareness of the latest treatment recommendations and coordinating multidisciplinary care involving a closer collaboration between PCPs and other HCPs17,48. While pharmacists can help monitor prescriptions, educate patients on the benefits of ICS-containing medications, and encourage them to seek medical advice before dispensing SABA OTC, address factors such as poor adherence and incorrect inhaler technique, identify patients at risk of suboptimal control and teach self-management strategies to achieve asthma control17,49, a greater involvement of specialists can help with referrals48, especially following an exacerbation16. In addition, quality improvement strategies, including professional development initiatives, audits, and feedback interventions, can assist in closing the gap between best practices and care delivery, thereby improving treatment outcomes50 without impacting workload51.

Since primary care is the cornerstone of a strong healthcare system9, it is essential that PCPs build strong partnerships with patients through shared decision-making, provision of training on self-management3 and effective communication skills to increase patient satisfaction, improve health outcomes3 and reduce healthcare resource utilisation52 without increasing the consultation time53. Notably, compared with patients who receive usual care, those who have greater involvement in treatment-related decisions through shared decision-making, where clinicians and patients negotiate a treatment regimen that accommodates patient goals and preferences, report significantly better clinical outcomes, in terms of quality of life, asthma-related healthcare utilisation, rescue medication use, lung function, and the likelihood of well-controlled asthma54. Therefore, PCPs can play a major part in encouraging patients to participate in treatment-related decisions and communicate their expectations and concerns3.

This study is not without limitations. Prescription data were used as a surrogate for actual medication use and do not provide information on medication adherence, potentially leading to an under-estimation or over-estimation of SABA use. Although OCS bursts were likely prescribed for managing asthma exacerbations, the association between SABA prescriptions and OCS bursts was not analysed. As asthma severity was classified by investigators (guided by GINA 2017 treatment steps), the underlying disease severity may have been misdiagnosed in some patients. However, a global, 3-year, prospective observational study of patients with asthma and/or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) from real-world clinical practice demonstrated that investigator-classified disease severity was associated with several clinical and spirometric factors, including exacerbation history and symptom burden, in patients with asthma55. Owing to its observational nature, the study may also be prone to bias, e.g. therapies may be differently prescribed depending on disease severity56. In addition, as data for OTC purchase of SABA were self-reported, these findings may also be prone to recall bias56. Finally, as patients at many sites were predominantly recruited by specialists, results may not reflect primary care practices across all participating countries. However, aggregated data from 1440 patients across 24 countries, with a balanced distribution of those with mild and moderate-to-severe asthma, provide an understanding of global asthma management practices in the primary care setting.

In conclusion, results from 1440 patients from the SABINA III study treated in primary care reported that SABA prescriptions were common, with approximately one in every two patients being prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in the 12 months prior to the study visit (defined as over-prescription). Unregulated access to SABA was also common, with over one-fifth of patients purchasing SABA OTC, of whom approximately 40% purchased ≥3 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months. Among patients who purchased SABA OTC, most were already receiving SABA prescriptions, of whom over 70.0% received prescriptions for ≥3 SABA canisters. Higher SABA prescriptions (vs 1–2 canisters) were associated with poor asthma-related health outcomes. Prescription of OCS bursts was common across all SABA prescription categories, even in patients with low SABA prescriptions and mild asthma, regardless of asthma medications prescribed in the preceding 12 months. In addition, the level of asthma control was poor, with less than 50% of patients reporting well controlled asthma. Overall, these findings suggest misdiagnosis of disease severity and inappropriate prescribing practices, both of which are an important public health concern, necessitating professional development initiatives at the primary care level to reduce the burden of asthma. Policy changes to regulate SABA prescriptions and OTC purchase, while ensuring access to asthma medications, may help ensure that clinical practices are aligned with the current evidence-based treatment recommendations. Reducing SABA over-reliance at the primary care level and per current evidence-based guidelines may result in improved clinical outcomes.

Methods

Study design

SABINA III was a multi-country, observational, cross-sectional study conducted in 24 countries27. Patients were recruited from March 2019 to January 2020. Retrospective data from existing medical records and patient data collected during a study visit were entered into an eCRF. Data on exacerbation history and comorbidities and information on prescriptions for asthma medications were entered in the eCRF by physicians based on patient medical records. At the study visit, physicians also enquired as to whether patients had experienced exacerbations that were not captured in their medical records. Findings from the cohort of patients treated by PCPs are presented here.

The primary objective of the study was to describe SABA prescription patterns in the asthma patient population treated by PCPs at an aggregated multi-country level. The secondary objective was to determine the associations between SABA prescriptions and asthma-related health outcomes. In addition, prescriptions of OCS in patients stratified by SABA prescription categories (1–2 vs 3–5, 6–9, 10–12, and ≥13 canisters), investigator-classified asthma severity, and SABA monotherapy and ICS-containing treatments were evaluated post hoc.

The study was conducted in accordance with the study protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki, and local ethics committees. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal guardians per country regulations.

Study population

Eligible patients included those aged ≥12 years, with a documented diagnosis of asthma, ≥3 consultations with their HCP, and medical records containing data for ≥12 months prior to the study visit. Patients with a diagnosis of other chronic respiratory diseases, such as COPD, or with an acute or chronic condition that, in the opinion of the investigator, would limit their ability to participate in the study were excluded. Potential study sites were selected using purposive sampling with the aim of obtaining a sample representative of asthma treatment patterns within each participating country by a national coordinator, who also facilitated the selection of investigators.

Study variables

SABA prescriptions in the 12 months before the study visit were recorded and categorised as 0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–12, and ≥13 canisters. Prescription of ≥3 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months was defined as over-prescription57. For consistency across the whole SABINA programme, one SABA canister was assumed to contain 150 inhalations57. ICS canister prescriptions in the 12 months before the study visit were recorded and expressed according to the average daily dose (low, medium, or high).

Secondary variables included investigator-classified asthma severity (guided by GINA 2017 treatment steps [steps 1−2: mild asthma; steps 3−5: moderate-to-severe asthma] either in the study protocol or via a pop-up window in the eCRF)40, asthma duration, and prescriptions for asthma medications in the 12 months prior to the study visit (SABA monotherapy, SABA in addition to maintenance therapy, ICS or fixed-dose combination of ICS/LABAs, and OCS burst treatment [defined as a short course of intravenous corticosteroids or OCS administered for 3−10 days or a single dose of an intramuscular corticosteroid to treat an exacerbation]). All patients were also asked about pharmacy purchases of OTC SABA without a prescription, irrespective of whether individual countries permitted SABA purchase OTC; these data were subsequently entered in the eCRF by the investigator. Other variables, including healthcare insurance (not reimbursed, partially reimbursed, or fully reimbursed), education level (primary and secondary school, high school or university and/or post-graduate education), BMI, number of comorbidities, and smoking status, were also recorded.

Outcomes

Asthma symptom control was evaluated according to the GINA 2017 assessment for asthma control40 and categorised as well controlled, partly controlled, and uncontrolled. Severe exacerbations in the preceding 12 months were based on the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society recommendations58 and defined as a deterioration in asthma resulting in hospitalisation or emergency room treatment or the need for intravenous corticosteroids or OCS for ≥3 days or a single dose of an intramuscular corticosteroid.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted at the overall country-aggregated population level. The association of SABA prescriptions (1–2 vs 3–5, 6–9, 10–12, and ≥13 canisters) in the previous 12 months with the incidence rate of severe exacerbations and the odds of achieving at least partly controlled asthma (uncontrolled asthma as the reference) was analysed using negative binomial and logistic regression models, respectively.

The regression models, based on complete-case analyses, were adjusted for pre-specified covariates and potential confounders (based on the literature and modelling data from SABINA I18). Both ORs and IRRs were adjusted for the same pre-specified covariates (age, country, sex, and smoking as pre-specified covariates); however, the adjustments differed in the potential confounders used in the two regression models (GINA step by investigator, healthcare insurance, education level, comorbidities, duration of asthma, and BMI were used for ORs, while duration of asthma and BMI were used for IRRs [age, duration of asthma, and BMI as continuous variables; others as categorical or ordinal variables]). Patients with zero SABA prescriptions were excluded from the analyses as it was not possible to determine the alternative reliever medication used. To ensure that the overall SABINA III study was adequately powered, the aim was to enrol up to 500 patients from each participating country, with 20−25 patients recruited from each participating site. All statistical tests were two-sided at a 5% level of significance and were performed using R statistical software (version 3.6.0).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.

References

Global Asthma Network (GAN). The Global Asthma Report 2018. http://www.globalasthmareport.org [Accessed March 22, 2021] (2018).

World Health Organization. Asthma. Key Facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma [Accessed May 22, 2022] (2022).

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. http://ginasthma.org/ [Accessed June 20, 2022] (2022).

Laforest, L. et al. Management of asthma in patients supervised by primary care physicians or by specialists. Eur. Respir. J. 27, 42–50 (2006).

Price, D., Fletcher, M. & van der Molen, T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: The REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 24, 14009 (2014).

Levy, M. L. et al. International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) Guidelines: Diagnosis of respiratory diseases in primary care. Prim. Care Respir. J. 15, 20–34 (2006).

Fletcher, M. J. et al. Improving primary care management of asthma: Do we know what really works? NPJ Prim. Care. Respir. Med. 30, 29 (2020).

Honkoop, P. J. et al. Adaptation of a difficult-to-manage asthma programme for implementation in the Dutch context: A modified e-Delphi. NPJ Prim. Care. Respir. Med. 27, 16086 (2017).

World Health Organization. Primary healthcare. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care [Accessed April 22, 2021] (2021).

World Health Organization. Global spending on health: A world in transition. https://www.who.int/health_financing/documents/health-expenditure-report-2019.pdf [Accessed June 22, 2021] (2019).

Irving, G. et al. International variations in primary care physician consultation time: A systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open 7, e017902 (2017).

Chapman, K. R. Impact of ‘mild’ asthma on health outcomes: Findings of a systematic search of the literature. Respir. Med. 99, 1350–1362 (2005).

Tirimanna, P. R. et al. Prevalence of asthma and COPD in general practice in 1992: Has it changed since 1977? Br. J. Gen. Pract. 46, 277–281 (1996).

Yeh, S. Y. & Schwartzstein, R. Asthma, Health and Society (eds Harver, H. & Kotses, H.) (Springer, 2009).

Levy, M. L. Guideline-defined asthma control: A challenge for primary care. Eur. Respir. J. 31, 229–231 (2008).

Levy, M. L. The national review of asthma deaths: What did we learn and what needs to change? Breathe 11, 14–24 (2015).

Bosnic-Anticevich, S. Z. Asthma management in primary care: Caring, sharing and working together. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 1043–1046 (2016).

Bloom, C. I. et al. Asthma-related health outcomes associated with short-acting beta2-agonist inhaler use: An observational UK Study as part of the SABINA Global Program. Adv. Ther. 37, 4190–4208 (2020).

Hull, S. A. et al. Asthma prescribing, ethnicity and risk of hospital admission: An analysis of 35,864 linked primary and secondary care records in East London. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 26, 16049 (2016).

Yang, J. F. et al. Insights into frequent asthma exacerbations from a primary care perspective and the implications of UK National Review of Asthma Deaths recommendations. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 28, 35 (2018).

Anis, A. H. et al. Double trouble: Impact of inappropriate use of asthma medication on the use of health care resources. CMAJ 164, 625–631 (2001).

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. http://ginasthma.org/ [Accessed March 22, 2021] (2019).

Nguyen, V. N., Nguyen, Q. N., Le An, P. & Chavannes, N. H. Implementation of GINA guidelines in asthma management by primary care physicians in Vietnam. Int. J. Gen. Med. 10, 347–355 (2017).

Kaplan, A. et al. GINA 2020: Potential impacts, opportunities and challenges for primary care. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.12.035 (2020).

Ding, B. & Small, M. Disease burden of mild asthma: Findings from a cross-sectional real-world survey. Adv. Ther. 34, 1109–1127 (2017).

O’Byrne, P. M. et al. Inhaled combined budesonide-formoterol as needed in mild asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1865–1876 (2018).

Bateman, E. D. et al. Short-acting β2-agonist prescriptions are associated with poor clinical outcomes of asthma: The multi-country, cross-sectional SABINA III study. Eur. Respir. J. 59, 2101402 (2022).

Gibson, P. et al. Association between availability of non-prescription beta 2 agonist inhalers and undertreatment of asthma. BMJ 306, 1514–1518 (1993).

Sa-Sousa, A. et al. High oral corticosteroid exposure and overuse of short-acting beta-2-agonists were associated with insufficient prescribing of controller medication: a nationwide electronic prescribing and dispensing database analysis. Clin. Transl. Allergy 9, 47 (2019).

Sullivan, P. W., Ghushchyan, V. H., Globe, G. & Schatz, M. Oral corticosteroid exposure and adverse effects in asthmatic patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141, 110–116 e117 (2018).

Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills? National Review of Asthma Deaths. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills. [Accessed March 22, 2021] (2015).

Boulet, L. P. et al. A guide to the translation of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) strategy into improved care. Eur. Respir. J. 39, 1220–1229 (2012).

Chapman, K. R., Boulet, L. P., Rea, R. M. & Franssen, E. Suboptimal asthma control: Prevalence, detection, and consequences in general practice. Eur. Respir. J. 31, 320–325 (2008).

Mintz, M. et al. Assessment of asthma control in primary care. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 25, 2523–2531 (2009).

Magnoni, M. S. et al. Asthma control in primary care: The results of an observational cross-sectional study in Italy and Spain. World Allergy Organ. J. 10, 13 (2017).

Stallberg, B. et al. Asthma control in primary care in Sweden: a comparison between 2001 and 2005. Prim. Care Respir. J. 18, 279–286 (2009).

Baddar, S., Jayakrishnan, B., Al-Rawas, O., George, J. & Al-Zeedy, K. Is clinical judgment of asthma control adequate?: A prospective survey in a tertiary hospital pulmonary clinic. Sultan. Qaboos. Univ. Med. J. 13, 63–68 (2013).

Boulet, L. P., Phillips, R., O’Byrne, P. & Becker, A. Evaluation of asthma control by physicians and patients: Comparison with current guidelines. Can. Respir. J. 9, 417–423 (2002).

Price, D. et al. Time for a new language for asthma control: results from REALISE Asia. J. Asthma Allergy 8, 93–103 (2015).

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. http://ginasthma.org/ [Accessed March 22, 2021] (2017).

Asher, I. et al. Calling time on asthma deaths in tropical regions-how much longer must people wait for essential medicines? Lancet Respir. Med. 7, 13–15 (2019).

Davidson, A. E., Klein, D. E., Settipane, G. A. & Alario, A. J. Access to care among children visiting the emergency room with acute exacerbations of asthma. Ann. Allergy 72, 469–473 (1994).

Ferris, T. G. et al. Insurance and quality of care for adults with acute asthma. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 17, 905–913 (2002).

Shaw, D. E. et al. Balancing the needs of the many and the few: Where next for adult asthma guidelines? Lancet Respir. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00021-7 (2021).

McIvor, A. & Kaplan, A. A call to action for improving clinical outcomes in patients with asthma. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 30, 54 (2020).

Ahmad, B. A., Khairatul, K. & Farnaza, A. An assessment of patient waiting and consultation time in a primary healthcare clinic. Malays. Fam. Phys. 12, 14–21 (2017).

Price, C. et al. Large care gaps in primary care management of asthma: A longitudinal practice audit. BMJ Open 9, e022506 (2019).

Yawn, B. P. & Wechsler, M. E. Severe asthma and the primary care provider: Identifying patients and coordinating multidisciplinary care. Am. J. Med. 130, 1479 (2017).

Armour, C. L. et al. Using the community pharmacy to identify patients at risk of poor asthma control and factors which contribute to this poor control. J. Asthma 48, 914–922 (2011).

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Closing the quality gap: A critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/asthmagap.pdf [Accessed March 22, 2021] (2007).

Evans, A. et al. Strategies that promote sustainability in quality improvement activities for chronic disease management in healthcare settings: A practical perspective. Qual. Prim. Care. 28, 55–60 (2020).

Cabana, M. D. et al. Impact of physician asthma care education on patient outcomes. Pediatrics 117, 2149–2157 (2006).

Clark, N. M. et al. The clinician-patient partnership paradigm: Outcomes associated with physician communication behavior. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila). 47, 49–57 (2008).

Wilson, S. R. et al. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181, 566–577 (2010).

Reddel, H. K. et al. Heterogeneity within and between physician-diagnosed asthma and/or COPD: NOVELTY cohort. Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.03927-2020 (2021).

Roche, N. et al. Quality standards for real-world research. Focus on observational database studies of comparative effectiveness. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 11, S99–S104 (2014).

Cabrera, C. S. et al. SABINA: Global programme to evaluate prescriptions and clinical outcomes related to short-acting beta2-agonist use in asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 55, 1901858 (2020).

Reddel, H. K. et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Asthma control and exacerbations: Standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 180, 59–99 (2009).

Acknowledgements

AstraZeneca funded all the SABINA studies and was involved in designing the study, developing the study protocol, conducting the study, and performing the analyses. AstraZeneca was given the opportunity to review the manuscript before submission and funded medical writing support. Writing and editorial support was provided in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3) and fully funded by AstraZeneca.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.P. contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. K.H. contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. J.D. contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. S.W.T. contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. C.J.M. contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. H.K.F. contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. M.J.H.I.B. designed the study and contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.P. has an advisory board membership with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Circassia, Viatris, Mundipharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Thermo Fisher; consultancy agreements with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Viatris, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Mundipharma, Novartis, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Theravance; grants and unrestricted funding for investigator-initiated studies (conducted through Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd) from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Circassia, Viatris, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Theravance, and UK National Health Service; payment for lectures/speaking engagements from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Viatris, Mundipharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva Pharmaceuticals; payment for travel/accommodation/meeting expenses from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Circassia, Mundipharma, Novartis, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Thermo Fisher; funding for patient enrolment or completion of research from Novartis; stock/stock options from AKL Research and Development Ltd., which produces phytopharmaceuticals; owns 74% of the social enterprise Optimum Patient Care Ltd (Australia and UK) and 74% of Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd (Singapore); 5% shareholding in Timestamp, which develops an adherence monitoring technology; is a peer reviewer for grant committees of the UK Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme and Health Technology Assessment; and was an expert witness for GlaxoSmithKline. K.H. reports personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Chiesi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Teva, Cipla, OPCA, Asthma Australia, and Spirometry Learning Australia, outside the submitted work. J.D. has nothing to disclose. S.W.T. has nothing to disclose. C.J.M. has nothing to disclose. H.K.F. is an employee of AstraZeneca. M.J.H.I.B. was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time this study was conducted.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Price, D., Hancock, K., Doan, J. et al. Short-acting β2-agonist prescription patterns for asthma management in the SABINA III primary care cohort. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 32, 37 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-022-00295-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-022-00295-7

This article is cited by

-

Effect of Individual Patient Characteristics and Treatment Choices on Reliever Medication Use in Moderate-Severe Asthma: A Poisson Analysis of Randomised Clinical Trials

Advances in Therapy (2024)

-

The Association Between Short-Acting β2-Agonist Over-Prescription, and Patient-Reported Acquisition and Use on Asthma Control and Exacerbations: Data from Australia

Advances in Therapy (2024)

-

Beware SABA Overuse: a Message from the Global SABINA Program

Current Treatment Options in Allergy (2023)

-

Over-the-counter use of short-acting beta-2 agonists: a systematic review

Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice (2022)