Abstract

Despite national recommendations, most patients with asthma are not given a written action plan . The objectives were to ascertain physicians’ endorsement of potential enablers to providing a written action plan, and the determinants and proportion, of physician-reported use of a written action plan. We surveyed 838 family physicians, paediatricians, and emergency physicians in Quebec. The mailed questionnaire comprised 102 questions on asthma management, 11 of which pertained to written action plan and promising enablers. Physicians also selected a case vignette that best corresponded to their practice and reported their management. The survey was completed by 421 (56%) physicians (250 family physicians, 115 paediatricians and 56 emergency physicians); 43 (5.2%) reported providing a written action plan to ≥70% of their asthmatic patients and 126 (30%) would have used a written action plan in the selected vignette. Most (>60%) physicians highly endorsed the following enablers: patients requesting a written action plan, adding a blank written action plan to the chart, receiving a copy of the written action plan completed by a consultant, receiving a monetary compensation for its completion, and having another healthcare professional explain the completed written action plan to patients. Four determinants were significantly associated with providing a written action plan: being a paediatrician (RR:2.1), treating a child (RR:2.0), aiming for long-term asthma control (RR:2.5), and being aware of national recommendations to provide a written action plan to asthmatic patients (RR:2.9). A small minority of Quebec physicians reported providing a written action plan to most of their patients, revealing a huge care gap. Several enablers to improve uptake, highly endorsed by physicians, should be prioritised in future implementation efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most patients with asthma have poor or suboptimal control of their disease with frequent symptoms, activity limitation, exacerbations, and health care resources consumption.1, 2 To maximise asthma control, international and national asthma guidelines recommend self-management asthma education, regular medical review, and the provision of a written action plan (WAP).3–5 A WAP is a personalised document that details how to maintain asthma control, what to do when losing control (i.e., when and what medication to increase or commence), and when to seek medical attention in case of loss of control.3 Strong evidence supports the beneficial effect on health outcomes of asthma education that included the provision of a WAP.6, 7 Importantly, randomised paediatric trials confirmed the individual contribution of WAP itself to increase treatment adherence, reduce exacerbations, and improve control of asthma, whether the WAP was used as an adjunct to asthma education,8, 9 or alone upon discharge from the emergency department.10 Yet, while patients have strongly endorsed their usefulness,11, 12 less than 30% of patients with asthma presenting to the acute care setting13, 14 or in general population surveys own a WAP15, 16.

To address this large care gap and increase the use of a WAP, successful implementation entails a higher provision of WAP by health care professionals and a better use of the WAP by patients and families with asthma. Most implementation trials have targeted patients and caregivers to promote the use of a WAP,17 with few aiming to facilitate the provision of a WAP by physicians.17, 18 Yet, multiple obstacles faced by physicians to provide a WAP have been identified: lack of time, lack of integration in the clinical routine, poor access to structured WAP templates, forgetfulness, lack of monetary compensation, and low perceived usefulness.19–21 To address the former three obstacles, a structured three-colour zone WAP was designed in triplicate, including the prescription, a chart copy, and the patient’s take-home plan, thus allowing simultaneous writing of all documents.22 The WAP combined with a prescription was shown to be effective in improving the quality of physician prescriptions, increasing patient adherence to prescriptions, and improving patient outcomes.23 Sponsored by the national institute of excellence in health and social services in Quebec, Canada, this WAP has been distributed freely to Quebec health care professionals since 2008. Unfortunately, availability and efficacy is generally insufficient to ensure implementation,24 as interventions shown effective in a trial setting may be difficult to implement in clinical practice.25 A successful implementation strategy must overcome the key barriers, facilitate behavioural changes, and offer acceptable, and effective implementation solutions.26 A novel approach to identify promising strategies consists in asking physicians to propose enablers perceived or experienced as effective and implementable in their own practice. Shown highly successful,27 this approach has lead to both important practice changes and improved health outcomes.27, 28 Along these lines, a number of enablers to facilitate the provision of the WAP were identified by physicians during individual qualitative interviews; the main ones pertained to clinic reorganisation of care and improved inter-professional asthma management.29

The main objective of this study was to ascertain physicians’ endorsement of promising enablers as identified by fellow physicians in the first phase of this research programme,29 to facilitate the provision of a WAP (Table 1). Secondary objectives aimed to identify the proportion of physicians reporting using a WAP and the determinants of the provision of this plan by physicians.

Results

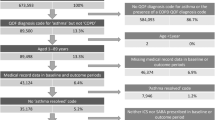

The survey was sent to 838 physicians, of whom 90 were found to be ineligible (retired, on leave or not seeing patients with asthma). Of the remaining 748 potentially eligible physicians, 421 (56%) physicians (250 family physicians, 115 paediatricians and 56 emergency physicians) returned the completed questionnaire (Fig. 1). Non-respondents were similar to respondents in their practice setting (rural vs. urban) and specialty, but differed significantly in sex (43% vs. 31% males, P < 0.001) and years of practice (20 vs. 13, P < 0.001). Respondents were predominantly female (69%), practicing in an urban (93%) and non-academic (56%) setting, and in practice for a median of 13 (5–21) years.

Only 43 (5.20%; 95% CI 2.71%, 7.68%) responders reported providing a WAP to 70% or more of their patients with asthma in their usual practice; they represented 27% of paediatricians, 4% of family physicians and less than 2% of emergency physicians. Approximately 60% of participants selected one of the acute care vignettes, with the remaining non-acute clinic vignettes equally distributed between the paediatric and adult cases.

Only 38.7% (32.8%, 44.5%) of physicians (61% of paediatricians, 38% of family physicians and 25% of emergency physicians) were aware of Canadian and international guidelines recommending the provision of a WAP to each patient. When notified of this recommendation, 58.7% (52.8%, 64.7%) of physicians (59% of family physicians, 49% of paediatricians and 39% of emergency physicians) expressed a high interest in attending a training session on how to efficiently complete and explain a WAP for patients.

Of the seven most promising enablers,29 five that were highly endorsed by the majority of responders as likely to increase their WAP use were: patients requesting a WAP, the addition of a blank copy of the WAP to the medical chart prior to the medical visit, receiving a copy of the WAP completed by the specialist or consultant, and the explanation to the patient of the WAP completed by the physician by a paramedical health professional and not by the physician himself. In addition, 67.3% (61.7, 73.0) of physicians stated that a monetary incentive would increase their provision of a WAP. Access to a WAP version for completion by computer and modification of the existing WAP were the only two enablers that were not highly endorsed (Fig. 2).

The graph depicts the proportion of physicians who reported, on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 0 to 6, whether the proposed enabler would change their use of a WAP. Answers 0 to 2 (would decrease use) represented by black (0), dark grey (1) and pale grey (2) bars; answer 3 (would not change use) is depicted by vertical lines displayed equally on either side of the central vertical line; and answers 4 to 6 (would increase use) are depicted by horizontal lines (4); diagonal lines (5), and white bars (6). The proportion of physicians responding 5 or 6, indicative of high endorsement of an experienced or anticipated increase in WAP use, is depicted in the bolded rectangular box and reported in the column on the right side, for each enabler

A total of 126 (30%) physicians would have provided a WAP to the patient in the selected case vignette; they are hereafter considered as ‘intenders’. Overall, four determinants were strongly associated (Odds ratio, OR > 2.0) with the intention to use a WAP in the case vignette, namely the selection of a paediatric vignette, having long-term control as a treatment goal, being aware of national recommendations to provide a WAP to each patient with asthma to be reviewed at each visit, and being a paediatrician (Table 2), The latter three determinants held true for the subgroup of physicians who choose one of the two paediatric case vignettes, whereas female physicians and awareness of national recommendations were the two main determinants in those that selected an adult vignette. Emergency physicians were the lowest intended providers of WAP (OR, 0.31 95% CI 0.11, 0.93).

Discussion

Main findings

In this group of randomly selected Quebec physicians, barely 5% reported routinely providing a WAP to their patients with asthma. About a third of them would have provided a WAP to the poorly controlled patient presented in the selected case vignette. To facilitate uptake of the WAP, physicians highly endorsed simple approaches to facilitate access to the WAP at the point of care, inter-professional management, the provision of monetary compensation, and patient request as key enablers to facilitate their provision of a WAP.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

Despite guidelines recommending its use for more than a decade,3–5 the proportion of physicians reporting regular use of a WAP for their patients with asthma remains abysmal. As the study did not focus on barriers but rather on potential solutions, the reason for such low use remains to be clarified. However, the intended use in the patient depicted in the case vignette was higher (30%), perhaps because of perceived higher need in view of their poor control. Indeed, physicians have consistently reported their selective use of WAP in patients they perceived more likely of benefitting because of more severe disease.29 The infrequent reported provision of WAP by physicians is concordant with the patient-reported WAP ownership rarely exceeding 30%, including among poorly controlled patients.15, 16, 30, 31 Even in the respiratory clinic of tertiary care centres, ownership of a WAP by asthmatic patients is often suboptimal at less than 50%.11

Of the seven enablers previously proposed by physicians in the first phase of this research programme,29 all but two were highly endorsed by physicians as likely to improve their delivery of WAP. Most physicians did not believe that a change in the template of the WAP, sponsored by the national institute of excellence in health and social services in Quebec, was required, perhaps due to the highly consultative approach to its development, the well-endorsed structured template, and the time saving by simultaneous writing of the patient’s take-home WAP, chart copy, and prescription.22 Access to a computerised version of the WAP was perceived as useful by just 45% of physicians, perhaps because of a low use of electronic medical records (EMR) at the time of this survey (not documented) or the inconvenience of having to print for patients both the prescription and coloured WAP version from the EMR (in absence of governmental-approved electronic transmission). This contrasts with the strikingly high-achieved provision rate (>93%) of WAP to children discharged from hospital, when it was integrated into the electronic medical record.32

In contrast, a simple practice organisation change, such as adding the WAP in the patient medical chart prior to the visit, was reported to be highly effective to increase physician’s personal use of the WAP. Consistent with the literature recognising the power of prompting on physician behaviour in general and for WAP in particular, a majority of respondents claimed that patient requests would markedly increase their provision of a WAP. Such an approach has been shown effective when the target behaviour has not been integrated into usual practice because of forgetfulness or inertia rather than non-agreement.33 Similarly, receiving the WAP completed by a specialist for a common patient suggests a domino effect of the positive example set by the specialist. Sending a copy of the WAP along with the consultation report and/or asking the patient to bring the WAP to the family physician are two readily implementable solutions. Indeed, the great majority of family physicians follow specialists’ recommendations and believe that consultants improve their own medical knowledge.34 With a lack of time reported as a key barrier to providing a WAP,20 the availability of a trained paramedical health professional (e.g., a nurse, respiratory technician or pharmacist) to explain the WAP to the patient, rather than the physician himself providing the explanation, was rated as a strong enabler, underlying the importance of inter-professional asthma management.18

Admitting their low awareness of guideline recommendations to provide or review the WAP at each visit, the overwhelming majority of physicians expressed a strong interest in attending a training session on how to efficiently complete and explain the WAP. These collective findings attest to the physicians’ general agreement with the four elements identified as likely to promote asthma plan delivery in Ring and colleagues’ theoretical model of action plan implementation, namely activities to support professional education, parent/carer education, partnership working, and communication.18 Finally, consistent with an American survey, in which half of physicians reported that the lack of a financial compensation was a barrier in providing adequate education to a patient newly diagnosed with asthma,20 most physicians indicated that a monetary incentive would positively affect their provision of a WAP, as shown in the Australia asthma 3+ visit plan.35 In several large health care systems, monetary incentives to pay physicians for their performance have shown increased efficiency and modest improvements in outcomes, but have raised issues regarding the validity of quality indicators on which to gauge performance, in this case WAP in paper or electronic version, and the added administrative requirements.36

Four determinants were strongly and independently linked to the physicians’ intention to provide a WAP. By far, the strongest determinant of the intention was the awareness of guideline recommendations, which was associated with a 3-fold higher odd of intention. Surprisingly and in contrast to other physician self-reports,31 the overwhelming majority of Quebec physicians caring for patients with asthma, primarily family physicians and emergency physicians, were unaware of the national and international recommendations to provide a WAP to each patient with asthma.37 Clearly, consensus guidelines have not adequately reached family physicians and emergency physicians. This reality calls for more effective strategies, such as delivering brief recommendations to clinicians via email.38 A novel finding was the strong association, independent from specialty, between the physician’s therapeutic objective to achieve long-term asthma control and the provision of a WAP, underlying the importance of disseminating this message to all physicians, irrespective of practice settings and specialty.

In line with previous reports,15, 39, 40 WAP was more frequently provided to children than adults in the case vignettes and more often used by paediatricians than by family physicians or emergency physicians. This begs the question as to whether the streetlight coloured WAP may be considered too childish for adults or whether written communication is perceived as less necessary in adults than children. While the effectiveness of asthma education including a WAP has been clearly established in both adults and children6, 7, 41, 42, the independent contribution of the WAP has only been demonstrated in children23 and is currently under review in adults,43 perhaps adding to the common, yet unproven, perception that these documents may not be useful or adapted for use by adults.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study must be interpreted in light of the following limitations. With a 56% participation rate, some of the analyses might have been underpowered, as we did not meet our target sample size. Also, we cannot rule out the possibility of a selection bias, as responders were more frequently women with fewer years of practice than non-responders and thus who might have been trained under more recent guidelines. This over representation of women and younger physicians selection bias is consistent with other studies done in the form of physician surveys.44 As for any survey, the findings represent reported intention, not observed practice. However, in view of the very low reported use of WAP, a social desirability bias is very unlikely. As we did not ask about reasons for non-use of the WAP, we cannot exclude the possibility that it may be due to perceived ineffectiveness or irrelevance to the physician clientele as frequently reported in qualitative studies.21, 31 Yet, the most highly endorsed enablers are targeting barriers faced by intended users rather than in non-intenders, suggesting a high receptivity of responders. Moreover, the high endorsement of enablers among all physicians, irrespective of their intended use or not of the WAP, suggests wide applicability.

The physicians we surveyed worked in a publicly funded health setting with free access to medical care, and where all patients are insured for their medication, either publically or privately. Asthma education centres with paramedical health care professionals and WAPs are readily available in Quebec caution is warranted before generalisation to other settings.

Implications for future research, policy and practice

Highly endorsed enablers offer the means to increase WAP use by physicians. These include patient-prompting, consultants’ sharing with primary care providers of the WAP issued to their patients, organisational changes to facilitate WAP access at the point of care, delegating to paramedical healthcare professionals the explanation of the WAP, and financial incentives.

Conclusion

In view of the very low reported use of the WAP by Quebec physicians, interventions to increase the awareness of guideline recommendations, of the importance of seeking long-term asthma control, and of the value of WAP in adults and in the acute care settings are likely to increase the intention to use WAP.

Methods

This paper reports a survey of randomly selected physicians in the province of Quebec, Canada and represents the second phase of a mixed methods research programme. In the first phase of the study,29 qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted in 42 physicians which identified 867 enablers of optimal asthma management including the use of WAP. Enablers were most frequently endorsed by interviewed physicians were reviewed using a 2-step Delphi approach by seven co-authors with different specialties to identify enablers most likely to be implementable for the questionnaire. The survey was then pretested in six physicians.

The research ethics board of the Sainte-Justine university health centre approved the study. The study was endorsed by the Institut national d’excellence en santé et services sociaux (INESSS), the Association des pédiatres du Québec, the Association des spécialistes en médecine d’urgence du Québec, and the Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec. Participants were notified by an information letter of study objectives; consent was assumed if they completed and returned the questionnaire.

Our survey methods have been described in details elsewhere.45 Briefly, participants were randomly selected from the list provided by the Collège des médecins du Québec, using a stratified sampling procedure based on specialty. Physicians were eligible if they were registered as family physicians, paediatricians, or emergency physicians in active practice in 2013 and reported seeing patients with asthma. As the INESSS has made available a WAP for asthma attacks since 2007, we specifically wished to include emergency physicians who often see patients during the initial exacerbation leading to the diagnosis of asthma and for subsequent exacerbations requiring health care consumption. Physicians who were retired, in training, or who had participated in the pre-test of the questionnaire or in phase-1 qualitative interviews29 were excluded and replaced.

The questionnaire was comprised of 102 questions. The first two sections included physician demographics and four case vignettes of a poorly controlled patient (a child or an adult presenting in a clinic or in an acute care setting) from which physicians chose the one vignette most closely representing their practice setting to anchor their treatment recommendations and means of communicating them to their patients. The next three sections pertained to beliefs, knowledge, and perceived facilitators regarding: the prescription of long-term inhaled corticosteroids; the provision of a WAP; and views on the expansion of pharmacists’ professional activities. The current article focuses on the 11 questions pertaining specifically on the WAP and seven promising enablers to increase WAP uptake in daily practice (Table 1).

Using the modified tailored design method, a written pre-notification letter was sent. Ten days later, we sent an information letter, the questionnaire, a copy of the WAP combined with a prescription,22, 46 a 25$ monetary incentive, and a pre-paid, pre-addressed return envelope. A reminder/thank you postal card was sent on day 21, followed by a second copy of the questionnaire on day 37 to the non-responders. Up to three phone calls were made to non-responders starting on day 38.

Statistics

A sample size of 500 physicians was required to obtain a 95% confidence interval of ± 0.10 for endorsement proportions of 50%. Assuming a 60% response rate, we send the questionnaire to 838 physicians.

The distribution of endorsement of enablers was reported as the percentage (95% CI), after adjustment for the stratified sampling by specialty with greater weight given to the responses of family physicians (91%), vs. paediatricians (7.6%) and emergency physicians (1.4%) to reflect the actual distribution of these specialties in the province of Quebec. We classified physicians as being in strong agreement with promising enablers if they responded 5 or 6 on the 7-point scale (0 to 6) or 4 or 5 on a 6-point scale (0 to 5) or yes to direct question. We displayed endorsement of enablers with diverging stacked bars charts. We further explored potential determinants of the provision of a WAP to the patient described in the clinical vignette using bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models. Potential determinants included: physician demographics, practice characteristics, and responses to case vignettes. As sampling was stratified by specialty, specialty was forced into all models. All tests were two-sided with estimates presented with 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were performed on SAS® software (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC 27513, USA). An OR with a 95% confidence interval between 0.9 and 1.1 was deemed indicative of equivalence. P-values less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance, with no correction for multiple testing.

References

Fitzgerald, J. M., Boulet, L. P., McIvor, R. A., Zimmerman, S. & Chapman, K. R. Asthma control in Canada remains suboptimal: The Reality of Asthma Control (TRAC) study. Can. Resp. J. 13, 253–259 (2006).

Rabe, K. F., Adachi, M. & Lai, C. K. et al. Worldwide severity and control of asthma in children and adults: The global asthma insights and reality surveys. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 114, 40–47 (2004).

GINA Global initiative for asthma P. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Global initiative for asthma 2015: http://www.ginasthma.org/.

British thoracic society Scottish intercollegiate guidelines network. British thoracic society Scottish intercollegiate guidelines network. British guideline on the management of asthma. Thorax. 69, i1–i192 (2014).

Lougheed, M. D., Lemiere, C. & Ducharme, F. M. et al. Canadian thoracic society 2012 guideline update: diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Can Resp. J. 19, 127–164 (2012).

Gibson, P. G., Coughlan, J., Abramson, M., Bauman, A., Hensley, M. J. & Walters, E. J. Self management education and regular practionner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane. Database. Syst. Rev. 4, CD001117 (1999).

Guevara, J. P., Wolf, F. M., Grum, C. M. & Clark, N. M. Effects of educational interventions for self management of asthma in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. Med. J. 326, 1308–1309 (2003).

Agrawal, S. K., Singh, M., Mathew, J. L. & Malhi, P. Efficacy of an individualized written home-management plan in the control of moderate persistent asthma: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta. Paediatr. 94, 1742–1746 (2005).

Zemek, R., Bhogal, S. K. & Ducharme, F. M. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining written action plans in children: what is the plan?. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 162, 157–163 (2008).

Ducharme F. M., Noya F., Rich H., et al. Randomized controlled trial of a multi-faceted intervention initiated in the emergency department (ED) to improve asthma control. Pediatr. Acad. Soc. 14, 52 (2009).

Beauchesne, M. F., Levert, V., El Tawil, M., Labrecque, M. & Blais, L. Action plans in asthma. Can. Resp. J. 13, 306–310 (2006).

Sulaiman, N. D., Barton, C. A. & Abramson, M. J. et al. Factors associated with ownership and use of written asthma action plans in North-West Melbourne. Prim. Care. Resp. J. 13, 211–217 (2004).

Camargo, C. A. Jr., Reed, C. R., Ginde, A. A., Clark, S., Emond, S. D. & Radeos, M. S. A prospective multicenter study of written action plans among emergency department patients with acute asthma. J. Asthma. 45, 532–538 (2008).

Cross, E., Villa-Roel, C. & Majumdar, S. R. et al. Action plans in patients presenting to emergency departments with asthma exacerbations: frequency of use and description of contents. Can. Respir. J. 21, 351–356 (2014).

CDC. Asthma facts. CDC’s national asthma control program Grantees. 2013:1015. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/pdfs/asthma_facts_program_grantees.pdf. (accessed Jan 2016)

Statistics ABo. Australian health survey: health service usage and health related actions 2011-2012. In: 43640DO007. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4364.0.55.002/Main+Features12011-12?OpenDocument (accessed Nov 1, 2016).

Ring, N., Malcolm, C. & Wyke, S. et al. Promoting the use of personal asthma action plans: a systematic review. Prim. Care. Respir. J. 16, 271–283 (2007).

Ring, N., Jepson, R. & Pinnock, H. et al. Developing novel evidence-based interventions to promote asthma action plan use: a cross-study synthesis of evidence from randomised controlled trials and qualitative studies. Trials. 13, 216 (2012).

Sheares, B. J., Du, Y., Vazquez, T. L., Mellins, R. B. & Evans, D. Use of written treatment plans for asthma by specialist physicians. Pediatr. Pulm. 42, 348–356 (2007).

Damon, S. A. & Tardif, R. R. Asthma education: different viewpoints elicited by qualitative and quantitative methods. J. Asthma. 52, 314–317 (2015).

Tan, N. C., Tay, I. H., Ngoh, A. & Tan, M. A qualitative study of factors influencing family physicians’ prescription of the written asthma action plan in primary care in Singapore. Singapore. Med. J. 50, 160–164 (2009).

Ducharme, F. M., Noya, F. & McGillivray, D. et al. Two for one: a self-management plan coupled with a prescription sheet for children with asthma. Can. Respir. J. 15, 347–354 (2008).

Ducharme, F. M., Zemek, R. L. & Chalut, D. S. et al. Written action plan in pediatric emergency room improves asthma prescribing, adherence and control. Am. Rev. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 183, 195–203 (2010).

Grimshaw, J. M., Thomas, R. E. & MacLennan, G. et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health. Technol. Assess. 8, iii–72 (2004).

Ring, N., Jepson, R. & Hoskins, G. et al. Understanding what helps or hinders asthma action plan use: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature. Patient. Educ. Couns. 85, e131–e143 (2011).

French, S. D., Green, S. E. & O’Connor, D. A. et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the theoretical domains framework. Implement. Sci. 7, 1–8 (2012).

Bhogal, S., McGillivray, D. & Bourbeau, J. et al. Focusing the focus group: impact of the awareness of major factors contributing to non-adherence to acute paediatric asthma guidelines. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 17, 160–167 (2010).

Zemek, R., Plint, A. & Osmond, M. H. et al. Triage nurse-initiation of corticosteroids in pediatric asthma is associated with improved ED efficiency. Pediatr. 129, 671–680 (2012).

Lamontagne, A. J., Pelaez, S. & Grad, R. et al. Facilitators and solutions for practicing optimal guided asthma self-management: the physician perspective. Can. Resp. J. 20, 285–293 (2013).

Cabana, M. D., Chaffin, D. C., Jarlsberg, L. G., Thyne, S. M. & Clark, N. M. Selective provision of asthma self-management tools to families. Pediatrics. 121, e900–e5 (2008).

Wiener-Ogilvie, S., Pinnock, H., Huby, G., Sheikh, A., Partridge, M. R. & Gillies, J. Do practices comply with key recommendations of the British asthma guideline? If not, why not?. Prim. Care. Respir. J. 16, 369–377 (2007).

Patel, S. J., Longhurst, C. A. & Lin, A. et al. Integrating the home management plan of care for children with asthma into an electronic medical record. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient. Saf. 38, 359–365 (2012).

Carlsen, B., Glenton, C. & Pope, C. Thou shalt versus thou shalt not: a meta-synthesis of GPs’ attitudes to clinical practice guidelines. Brit. J. Gen. Pract. 57, 971–978 (2007).

Berendsen, A. J., Kuiken, A., Benneker, W. H., Meyboom-de Jong, B., Voorn, T. B. & Schuling, J. How do general practitioners and specialists value their mutual communication? A survey. BMC. Health. Serv. Res. 9, 1–9 (2009).

Zwar, N. A., Comino, E. J., Hasan, I. & Harris, M. F. General practitioner views on barriers and facilitators to implementation of the asthma 3+ Visit Plan. Med. J. Aust. 183, 64–67 (2005).

Abduljawad, A. & Al-Assaf, A. F. Incentives for better performance in health care. Sultan. Qaboos. Univ. Med. J. 11, 201–206 (2011).

Lavoie, K. L., Rash, J. A. & Campbell, T. S. Changing provider behavior in the context of chronic disease management: focus on clinical inertia. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 6, 263–283 (2017). In press.

Grad, R., Pluye, P. & Repchinsky, C. et al. Physician assessments of the value of therapeutic information delivered via e-mail. Can. Fam. Physician. 60, e258–e62 (2014).

McNally, A. J., Frampton, C., Garrett, J. & Pattemore, P. Application of asthma action plans to childhood asthma: national survey repeated. N. Z. Med. J. 117, U932 (2004).

Prevention CfDCa. Asthma facts CDC’s national asthma control program grantees. (U.S. Department of health and human services, centers for disease control and prevention: Atlanta, GA, 2013).

Pinnock, H. & Thomas, M. Does self-management prevent severe exacerbations? Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 21, 95–102 (2015).

Boyd, M. L. T., McKean, M. C., Gibson, P. G., Ducharme, F. M. & Haby, M. Interventions for educating children who are at risk of asthma-related emergency department attendance. Cochrane. Database. Syst. Rev. 2, CD001290 (2009).

Evans J. W. D., et al. Personalised asthma action plans for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, Art. No.: CD011859 (2015).

Flanigan T. & McFarlane, E. S. Conducting survey research among physicians and other medical professionals: a review of current literature. Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods Section (AAPOR ’08) 2008, May:4136–4147.

Ducharme, F. M., et al. Enablers of physician prescription of a long-term asthma controller in patients with persistent asthma. Can. Resp. J. ID 4169010 (2016).

Action Plan for Asthma. https://www.inesss.qc.ca/en/publications/publications/publication.html?PublicationPluginController%5Bcode%5D=FICHE&PublicationPluginController%5Buid%5D=221&cHash=359e5d436ae7913d20f4afdb91e86116. (Accessed Mar 13 2015) (2011).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a grant (#233813) awarded through a peer-review process by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, Canada. We acknowledge the support of the Fonds de la Recherche du Québec en Santé for the infrastructure support provided to the Research Institutes of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine (CHUSJ). Simon Bacon was supported by a Chercheur-Boursier salary award from the Fonds de la Recherche du Québec en Santé and Kim Lavoie, by a New investigator award from the Canadian Institute of Health Research. We are indebted to Hélène Guay from the Institut national d’excellence en soins et services de santé for providing feedback on the interview questions pertaining to the WAP, Lucie Bergeron and Johanne St-Pierre for providing the list of the Collège des médecins du Québec, Benoît Mâsse for preparing the randomisation list, and Katia Lessard, Megan Jensen, Marie-France Goyer, Bhupendrasinh Chauhan and Annie Théorêt for assisting with the mailing of questionnaires and phoning of participants. This work was funded through a research grant (no 233813) of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). This work was presented in part at the annual Conference of the Respiratory Quebec Network in November 2015, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. This project was funded by a grant (#233813) awarded through a peer-review process by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Francine M. Ducharme conceived the protocol, obtained funding, oversaw the study, and assumes the overall responsibility for it. Lucie Blais, Simon L. Bacon, Pierre Ernst, Roland Grad, Kim L. Lavoie, and Martha L. McKinney contributed in the design and interpretation of the study results. Alexandrine J. Lamontagne coordinated the study. Eve Desplats analysed the data. Fabienne Djandji interpreted the data and draughted the manuscript under Ducharme’s supervision. All read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Francine M. Ducharme designed the WAP endorsed by the Institut national d’excellence en soins et services de santé and conducted a trial testing its efficacy. Other autors declare no conflict of interest with regards to this article.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Djandji, F., Lamontagne, A.J., Blais, L. et al. Enablers and determinants of the provision of written action plans to patients with asthma: a stratified survey of Canadian physicians. npj Prim Care Resp Med 27, 21 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0012-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0012-3

This article is cited by

-

A systematic review on the effectiveness and impact of clinical decision support systems for breathlessness

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2022)

-

IMP2ART systematic review of education for healthcare professionals implementing supported self-management for asthma

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2018)

-

Solving the mystery of the yellow zone of the asthma action plan

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2018)

-

Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI): enhancing reporting to improve care

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2017)