Abstract

Despite the recognition of two-dimensional (2D) systems as emerging and scalable host materials of single-photon emitters or spin qubits, the uncontrolled, and undetermined chemical nature of these quantum defects has been a roadblock to further development. Leveraging the design of extrinsic defects can circumvent these persistent issues and provide an ultimate solution. Here, we established a complete theoretical framework to accurately and systematically design quantum defects in wide-bandgap 2D systems. With this approach, essential static and dynamical properties are equally considered for spin qubit discovery. In particular, many-body interactions such as defect–exciton couplings are vital for describing excited state properties of defects in ultrathin 2D systems. Meanwhile, nonradiative processes such as phonon-assisted decay and intersystem crossing rates require careful evaluation, which competes together with radiative processes. From a thorough screening of defects based on first-principles calculations, we identify promising single-photon emitters such as SiVV and spin qubits such as TiVV and MoVV in hexagonal boron nitride. This work provided a complete first-principles theoretical framework for defect design in 2D materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optically addressable defect-based qubits offer a distinct advantage in their ability to operate with high fidelity under room temperature conditions1,2. Despite the tremendous progress made in years of research, systems that exist today remain inadequate for real-world applications. The identification of stable single-photon emitters (SPEs) in 2D materials has opened up a new playground for novel quantum phenomena and quantum technology applications, with improved scalability in device fabrication and leverage in doping spatial control, qubit entanglement, and qubit tuning3,4. In particular, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) has demonstrated that it can host stable defect-based SPEs5,6,7,8 and spin triplet defects9,10. However, persistent challenges must be resolved before 2D quantum defects can become the most promising quantum information platform. These challenges include the undetermined chemical nature of existing SPEs7,11, difficulties in the controlled generation of desired spin defects, and scarcity of reliable theoretical methods which can accurately predict critical physical parameters for defects in 2D materials due to their complex many-body interactions.

To circumvent these challenges, the design of promising spin defects by high-integrity theoretical methods is urgently needed. Introducing extrinsic defects can be unambiguously produced and controlled, which fundamentally solves the current issues of the undetermined chemical nature of existing SPEs in 2D systems. As highlighted by refs. 2,12, promising spin qubit candidates should satisfy several essential criteria: deep defect levels, stable high spin states, large zero-field splitting (ZFS), efficient radiative recombination, high intersystem crossing (ISC) rates, and long spin coherence and relaxation time. Using these criteria for theoretical screening can effectively identify promising candidates but requires theoretical development of first-principles methods, significantly beyond the static and mean-field level. For example, accurate defect charge transition levels in 2D materials necessitates careful treatment of defect charge corrections for removal of spurious charge interactions13,14,15 and electron correlations for non-neutral excitation, e.g. from GW approximations15,16 or Koopmans-compliant hybrid functionals17,18,19,20. Optical excitation and exciton radiative lifetime must account for defect–exciton interactions, e.g. by solving the Bethe–Salpeter equation (BSE), due to large exciton-binding energies in 2D systems21,22. Spin-phonon relaxation time calls for a general theoretical approach to treat complex symmetry and state degeneracy of defective systems, along the line of recent development based on ab-initio density matrix approach23. Spin coherence time due to the nuclei spin and electron spin coupling can be accurately predicted for defects in solids by combining first-principles and spin Hamiltonian approaches24,25. In the end, nonradiative processes, such as phonon-assisted nonradiative recombination, have been recently computed with first-principles electron–phonon couplings for defects in h-BN26, and resulted in less competitive rates than corresponding radiative processes. However, the spin–orbit-induced ISC as the key process for pure spin state initialization during qubit operation has not been investigated for spin defects in 2D materials from first-principles in-depth.

This work has developed a complete theoretical framework which enables the design of spin defects based on the critical physical parameters mentioned above and highlighted in Fig. 1a. We employed state-of-the-art first-principles methods, focusing on many-body interaction such as defect–exciton couplings and dynamical processes through radiative and nonradiative recombinations. We developed a methodology to compute nonradiative ISC rates with an explicit overlap of phonon wavefunctions beyond current implementations in the Huang–Rhys approximation27. We showcase the discovery of transition metal complexes such as Ti and Mo with a vacancy (TiVV and MoVV) to be spin triplet defects in h-BN, and the discovery of SiVV to be a bright SPE in h-BN. We predict TiVV and MoVV are stable triplet defects in h-BN (which is rare considering the only known such defect is \({\,\text{V}}_{\text{B}\,}^{-}\)28) with large ZFS and spin-selective decay, which will set 2D quantum defects at a competitive stage with NV center in diamond for quantum technology applications.

a Schematic of the screening criteria and workflow developed in this work, where we first search for defects with stable triplet ground state, followed by large zero-field splitting (ZFS), then "bright'' optical transitions between defect states required for SPEs or qubit operation by photon, and at the end large intersystem crossing rate (ISC) critical for pure spin state initialization. b Divacancy site in h-BN corresponding to adjacent B and N vacancies (denoted by VB and VN). c Top-view and d side-view of a typical doping configuration when placed at the divacancy site, denoted by XVV. Atoms are distinguished by color: gray = N, green = B, purple = Mo, blue = Ti, red = X (a generic dopant).

Results

In the development of spin qubits in 3D systems (e.g. diamond, SiC, and AlN), defects beyond sp dangling bonds from N or C have been explored. In particular, large metal ions plus anion vacancy in AlN and SiC were found to have potential as qubits due to triplet ground states and large ZFS29. Similar defects may be explored in 2D materials30, such as the systems shown in Fig. 1b–d. This opens up the possibility of overcoming the current limitations of the uncontrolled and undetermined chemical nature of 2D defects, and unsatisfactory spin-dependent properties of existing defects. In the following, we will start the computational screening of spin defects with static properties of the ground state (spin state, defect formation energy, and ZFS) and the excited state (optical spectra), then we will discuss dynamical properties including radiative and nonradiative (phonon-assisted spin conserving and spin-flip) processes, as the flow chart shown in Fig. 1a. We will summarize the complete defect discovery procedure and discuss the outlook at the end.

Screening triplet spin defects in h-BN

To identify stable qubits in h-BN, we start by screening neutral dopant-vacancy defects for a triplet ground state based on total energy calculations of different spin states at both semi-local Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) and hybrid functional levels. We considered the dopant substitution at a divacancy site in h-BN (Fig. 1b) for four different elemental groups. The results of this procedure are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 and Note 1. With additional supercell tests in Supplementary Table 2, our screening process finally yielded that only MoVV and TiVV have a stable triplet ground state. We further confirmed the thermodynamic charge stability of these defect candidates via calculations of defect formation energy and charge transition levels. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, both TiVV and MoVV defects have a stable neutral (q = 0) region for a large range of Fermi levels (εF), from 2.2 to 5.6 eV for MoVV and from 2.9 to 6.1 eV for TiVV. These neutral states will be stable in intrinsic h-BN systems or with weak p-type or n-type doping (see Supplementary Note 2).

With a confirmed triplet ground state, we next computed the two defects’ ZFS. A large ZFS is necessary to isolate the ms = ± 1 and ms = 0 levels even at zero magnetic field allowing for controllable preparation of the spin qubit. Here we computed the contribution of spin–spin interaction to ZFS by implementing the plane-wave-based method developed by Rayson et al. (see the “Methods” section for details of implementation and benchmark on NV center in diamond)31. Meanwhile, the spin–orbit contribution to ZFS was computed with the ORCA code. We find that both defects have sizable ZFS including both spin–spin and spin–orbit contributions (axial D parameter) of 19.4 GHz for TiVV and 5.5 GHz for MoVV, highlighting the potential for the basis of a spin qubit with optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) (see Supplementary Note 3 and Fig. 2). They are notably larger than previously reported values for ZFS of other known spin defects in solids29, although at a reasonable range considering large ZFS values (up to 1000 GHz) in transition-metal complex molecules32.

Screening SPE defects in h-BN

To identify SPEs in h-BN, we considered a separate screening process of these dopant-vacancy defects, targeting those with desirable optical properties. Namely, an SPE efficiently emits a single photon at a time at room temperature. Physically this corresponds to identifying defects that have a single bright intra-defect transition with a high quantum efficiency (i.e. much faster radiative rates than nonradiative ones), for example current SPEs in h-BN have radiative lifetimes ~1–10 ns and quantum efficiency over 50%33,34.

Using these criteria we screened the defects by computing their optical transitions and radiative lifetime at random phase approximation (RPA) (see Supplementary Note 4, Fig. 3, and Table 3). This offers a cost-efficient first-pass to identify defects with bright transition and short radiative lifetime as potential candidates for SPEs. From this procedure, we found that CVV(T), SiVV(S), SiVV(T), SVV(S), GeVV(S), and \({{\rm{Sn}}}_{{\rm{VV}}}\)(S) could be promising SPE defects ((T) denotes triplet; (S) denotes singlet), with a bright intra-defect transition and radiative lifetimes on the order of 10 ns, at the same order of magnitude of the SPEs’ lifetime observed experimentally34. Among these, SiVV(S) has the shortest radiative lifetime, and in addition, Si has recently been experimentally detected in h-BN with samples grown in chemical vapor deposition (the ground state of SiVV is also singlet)35. Hence we will focus on SiVV as an SPE candidate in the following sections as we compute optical and electronic properties at higher level of theory from many-body perturbation theory including accurate electron correlation and electron–hole interactions. Note that CVV (commonly denoted CBVN) has also been suggested to be an SPE source in h-BN36.

Single-particle levels, optical spectra, and radiative lifetime

The single-particle energy levels of TiVV, MoVV, and SiVV are shown in Fig. 2. These levels are computed by many-body perturbation theory (G0W0) for accurate electron correlation, with hybrid functional (PBE0(α), α = 0.41 based on the Koopmans’ condition17) as the starting point to address self-interaction errors for 3d transition metal defects37,38. For example, we find that both the wavefunction distribution and ordering of defect states can differ between PBE and PBE0(α) (see Supplementary Figs. 4–6). The convergence test of G0W0 can been found in Supplementary Fig. 7, Note 5, and Table 4. Importantly, the single particle levels in Fig. 2 show there are well-localized occupied and unoccupied defect states in the h-BN bandgap, which yield the potential for intra-defect transitions.

Single-particle defect levels (horizontal black lines) of the a TiVV, b MoVV, and c SiVV defects in h-BN, calculated at G0W0 with PBE0(α) starting wavefunctions. The blue/red area corresponds to the valence/conduction band of h-BN. States are labeled by their ordering and representation within the CS group with up/down arrows indicating spin and filled/unfilled arrows indicating occupation. A red arrow is drawn to denote the intra-defect optical transition found in Fig. 3. Defect wavefunctions at PBE0(α) are shown with an isosurface value of 10% of the maximum. The blue and yellow color denotes different signs of wavefunctions.

Obtaining reliable optical properties of these two-dimensional materials necessitates solving the BSE to include excitonic effects due to their strong defect–exciton coupling, which is not included in RPA calculations (see comparison in Supplementary Fig. 8 and Table 5)39,40,41,42. The BSE optical spectra are shown for each defect in Fig. 3a–c (the related convergence tests can be found in Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). In each case, we find an allowed intra-defect optical transition (corresponding to the lowest energy peak as labeled in Fig. 3a–c, and red arrows in Fig. 2). From the optical spectra we can compute their radiative lifetimes as detailed in the “Methods” section on “Radiative recombination”. We find the transition metal defects’ radiative lifetimes (tabulated in Table 1) are long, exceeding μs. Therefore, they are not good candidates for SPE. In addition, while they still are potential spin qubits with optically allowed intra-defect transitions, optical readout of these defects will be difficult. Referring to Table 1 and the expression of radiative lifetime in Eq. (9) we can see this is due to their low excitation energies (E0, in the infrared region) and small dipole moment strength (\({\mu }_{\mathrm {e-h}}^{2}\)). The latter is related to the tight localization of the excitonic wavefunction for TiVV and MoVV (shown in Fig. 3d–f), as strong localization of the defect-bound exciton leads to weaker oscillator strength43.

Absorption spectra of the a TiVV, b MoVV, and c SiVV defects in h-BN at the level of G0W0 + BSE@PBE0(α). The left and right panels provide absorption spectra for two different energy ranges, where the former is magnified by a factor of 40 for TiVV and MoVV and a factor of 5 for SiVV for increasing visibility. A spectral broadening of 0.02 eV is applied. The exciton wavefunctions of d TiVV, e MoVV and f SiVV are shown on the right for the first peak.

On the other hand, the optical properties of the SiVV defect are quite promising for SPEs, as Fig. 3c shows it has a very bright optical transition in the ultraviolet region. As a consequence, we find that the radiative lifetime (Table 1) for SiVV is 22.8 ns at G0W0 + BSE@PBE0(α). We note that although the lifetime of SiVV at the level of BSE is similar to that obtained at RPA (13.7 ns), the optical properties of 2D defects at RPA are still unreliable, due to the lack of excitonic effects. For example, the excitation energy (E0) can deviate by ~1 eV and oscillator strengths (\({\mu }_{{\mathrm {e-h}}}^{2}\)) can deviate by an order of magnitude (more details can be found in Supplementary Table 5). Above all, the radiative lifetime of SiVV is comparable to experimentally observed SPE defects in h-BN34, showing that SiVV is a strong SPE defect candidate in h-BN.

Multiplet structure and excited-state dynamics

Finally, we discuss the excited-state dynamics of the spin qubit candidates TiVV and MoVV defects in h-BN, where the possibility of ISC is crucial. This can allow for polarization of the system to a particular spin state by optical pumping, required for realistic spin qubit operation.

An overview of the multiplet structure and excited-state dynamics is given in Fig. 4 for the TiVV and MoVV defects. For both defects, the system will begin from a spin-conserved optical excitation from the triplet ground state to the triplet excited state, where next the excited state relaxation and recombination can go through several pathways. The excited state can directly return to the ground state via a radiative (red lines) or nonradiative process (dashed dark blue lines). For the TiVV defect shown in Fig. 4a, we find the system may relax to another excited state with lower symmetry through a pseudo-Jahn–Teller distortion (PJT; solid dark blue lines), and ultimately recombine back to the ground state nonradiatively. Most importantly, a third pathway is to nonradiatively relax to an intermediate singlet state through a spin–flip ISC and then again recombine back to the ground state (dashed light-blue lines). This ISC pathway is critical for the preparation of a pure spin state, similar to the NV center in diamond. Below, we will discuss our results for the lifetime of each radiative or nonradiative process, in order to determine the most competitive pathway under the operation condition.

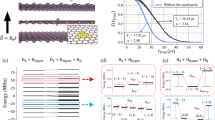

Multiplet structure and related radiative and nonradiative recombination rates of the a TiVV defect and the b MoVV defect in h-BN, computed at T = 10 K. The radiative process is shown in red with zero-phonon line (ZPL) and radiative lifetime (τR); the ground state nonradiative recombination (τNR) is denoted with a dashed line in dark blue; and finally the intersystem crossing (ISC) to the singlet state from the triplet excited state is shown in light blue. The zero-field splitting (D) is denoted by the orange line. For the TiVV defect, the pseudo-Jahn–Teller (PJT) process is shown with a solid line in dark blue.

Direct radiative and nonradiative recombination

First, we will consider the direct ground state recombination processes. Figure 5 shows the configuration diagram of the TiVV and MoVV defects. The zero-phonon line (ZPL) for direct recombination can be accurately computed by subtracting its vertical excitation energy computed at BSE (0.56 eV for TiVV and 1.08 eV for MoVV) by its relaxation energy in the excited state (i.e. Franck–Condon shift44, ΔEFC in Fig. 5). This yields ZPLs of 0.53 and 0.91 eV for TiVV and MoVV, respectively. Although this method accurately includes both many-body effects and Franck–Condon shifts, it is difficult to evaluate ZPLs for the triplet to singlet-state transition currently. Therefore, we compared it with the ZPLs computed by the constrained occupation DFT (CDFT) method at PBE. This yields ZPLs of 0.49 and 0.92 eV for TiVV and MoVV, respectively, which are in great agreement with the ones obtained from BSE excitation energies subtracting ΔEFC above. Lastly, the radiative lifetimes for these transitions are presented in Table 1 as discussed in the earlier section, which shows TiVV and MoVV have radiative lifetimes of 195 and 33 μs, respectively (red lines in Fig. 4).

Configuration diagram of the a TiVV defect and b MoVV defect in h-BN. The potential energy surfaces for each state are as follows: the triplet ground state in black, triplet excited state in blue, and for the TiVV defect the pseudo-Jahn–Teller triplet excited state in red. The zero-phonon lines (ZPL) are given as the energetic separation between the minima of the respective potential energy surfaces, along with the corresponding Huang–Rhys factors (S). The dashed black line represents the vertical excitation energy between triplet ground and excited states, and ΔEFC represents relaxation energy to equilibrium geometry at the excited state.

In terms of nonradiative properties, the small Huang–Rhys (Sf) for the \(|_{1}^{3}A^{\prime\prime} \rangle\) to \(|_{0}^{3}A^{\prime\prime} \rangle\) the transition of the TiVV defect (0.91) implies extremely small electron–phonon coupling and potentially an even slower nonradiative process. On the other hand, Sf for the \(|_{1}^{3}A\rangle\) to \(|_{0}^{3}A\rangle\) the transition of the MoVV defect is sizable (22.05) and may indicate a possible nonradiative decay. Following the formalism presented in ref. 26, we computed the nonradiative lifetime of the ground state direct recombination (T = 10 K is chosen to compare with the measurement at cryogenic temperatures45). Consistent with their Huang–Rhys factors, the nonradiative lifetime of TiVV is found to be 10 s, while the nonradiative lifetime of the MoVV defect is found to be 0.02 μs. The former lifetime is indicative of a forbidden transition; however, the TiVV defect also possesses a PJT effect in the triplet excited state (red curve in Fig. 5a). Due to the PJT effect, the excited state (CS, \(|_{1}^{3}A^{\prime\prime}\rangle\)) can relax to lower symmetry (C1, \(|_{1}^{3}A\rangle\)) with a nonradiative lifetime of 394 ps (solid dark blue line in Fig. 4a, additional details see Supplementary Note 9 and Fig. 11). Afterward, nonradiative decay from \(|_{1}^{3}A\rangle\) to the ground state (\(|_{0}^{3}A^{\prime\prime} \rangle\)) (dashed dark blue line in Fig. 4a) exhibits a lifetime of 0.044 ps due to a large Huang–Rhys factor (14.95).

Spin–orbit coupling (SOC) and nonradiative ISC rate

Lastly, we considered the possibility of an ISC between the triplet excited state and the singlet ground state for each defect, which is critical for spin qubit application. In order for a triplet to singlet transition to occur, a spin-flip process must take place. For ISC, typically SOC can entangle triplet and singlet states yielding the possibility for a spin-flip transition. To validate our methods for computing SOC (see the “Methods” section), we first computed the SOC strengths for the NV center in diamond. We obtained SOC values of 4.0 GHz for the axial λz and 45 GHz for non-axial λ⊥ in fair agreement with previously computed values and experimentally measured values27,46. We then computed the SOC strength for the TiVV defect (λz = 149 GHz, λ⊥ = 312 GHz) and the MoVV defect (λz = 16 GHz, λ⊥ = 257 GHz). The value of λ⊥ in particular leads to the potential for a spin-selective pathway for both defects, analogous to NV center in diamond.

To compute the ISC rate, we developed an approach which is a derivative of the nonradiative recombination formalism presented in Eq. (11):

Compared with previous formalism27, this method allows different values for initial state vibrational frequency (ωi) and final state one (ωf) through explicit calculations of phonon wavefunction overlap. Again to validate our methods we first computed the ISC rate for NV center in diamond. Using the experimental value for λ⊥ we obtain an ISC rate for NV center in diamond of 2.3 MHz which is in excellent agreement with the experimental value of 8 and 16 MHz45. In final, we obtain an ISC time of 83 ps for TiVV and 2.7 μs for MoVV as shown in Table 2 and light blue lines in Fig. 4.

The results of all the nonradiative pathways for the two spin defects are summarized in Table 2 and are displayed in Fig. 4 along with the radiative pathway. We begin by summarizing the results for TiVV first and then discuss MoVV below. In short, for TiVV the spin conserved optical excitation from the triplet ground state \(|_{0}^{3}A^{\prime\prime} \rangle\) to the triplet excited state \(|_{1}^{3}A^{\prime\prime} \rangle\) cannot directly recombine nonradiatively due to a weak electron–phonon coupling between these states. In contrast, a nonradiative decay is possible via its PJT state (\(|_{1}^{3}A\rangle\)) with a lifetime of 394 ps. Finally, the process of ISC from the triplet excited state \(|_{1}^{3}A^{\prime\prime}\rangle\) to the singlet state (\(|_{0}^{1}A^{\prime} \rangle\)) is an order of magnitude faster (i.e. 83 ps) and is in-turn a dominant relaxation pathway. Therefore the TiVV defect in h-BN is predicted to have an expedient spin purification process due to a fast ISC with a rate of 12 GHz. We note that while the defect has a low optical quantum yield and is predicted to not be a good SPE candidate, it is still noteworthy, as to date the only discovered triplet defect in h-BN is the negatively charged boron vacancy, which also does not exhibit SPE and has similarly low quantum efficiency9. Meanwhile, the leveraged control of an extrinsic dopant can offer advantages in spatial and chemical nature of defects.

For the MoVV defect, its direct nonradiative recombination lifetime from the triplet excited state \(|_{1}^{3}A\rangle\) to the ground state \(|_{0}^{3}A\rangle\) is 0.02 μs. While the comparison with its radiative lifetime (33 μs) is improved compared to the TiVV defect, it still is predicted to have low quantum efficiency. However, again the ISC between \(|_{1}^{3}A\rangle\) and \(|_{0}^{1}A\rangle\) is competitive with a lifetime of 2.7 μs. This rate (around MHz) is similar to diamond and implies a feasible ISC. Owing to its more ideal ZPL position (~1eV) and improved quantum efficiency, optical control of the MoVV defect is seen as more likely and may be further improved by other methods such as coupling to optical cavities47,48 and applying strain5,26.

Discussion

In summary, we proposed a general theoretical framework for identifying and designing optically addressable spin defects for the future development of quantum emitter and quantum qubit systems. We started by searching for defects with triplet ground state by DFT total energy calculations which allow for rapid identification of possible candidates. Here we found that the TiVV and MoVV defects in h-BN have a neutral triplet ground state. We then computed ZFS of secondary spin quantum sublevels and found they are sizable for both defects, larger than that of NV center in diamond, enabling possible control of these levels for qubit operation. In addition, we screened for potential SPEs in h-BN based on allowed intra-defect transitions and radiative lifetimes, leading to the discovery of SiVV. Next, the electronic structure and optical spectra of each defect were computed from many-body perturbation theory. Specifically, the SiVV defect is shown to possess an exciton radiative lifetime similar to experimentally observed SPEs in h-BN and is a potential SPE candidate. Finally, we analyzed all possible radiative and nonradiative dynamical processes with first-principles rate calculations. In particular, we identified a dominant spin-selective decay pathway via ISC at the TiVV defect which gives a key advantage for initial pure spin state preparation and qubit operation. Meanwhile, for the MoVV defect, we found that it has the benefit of improved quantum efficiency for more realistic optical control.

This work emphasizes that the theoretical discovery of spin defects requires careful treatment of many-body interactions and various radiative and nonradiative dynamical processes such as ISC. We demonstrate the high potential of extrinsic spin defects in 2D host materials as qubits for quantum information science. Future work will involve further examination of spin coherence time and its dominant decoherence mechanism, as well as other spectroscopic fingerprints from first-principles calculations to facilitate experimental validation of these defects.

Methods

First-principles calculations

In this study, we used the open source plane-wave code Quantum ESPRESSO49 to perform calculations on all structural relaxations and total energies with optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt (ONCV) pseudopotentials50 and a wavefunction cutoff of 50 Ry. A supercell size of 6 × 6 or higher was used in our calculations with a 3 × 3 × 1 k-point mesh. Charged cell total energies were corrected to remove spurious charge interactions by employing the techniques developed in refs. 15,51,52 and implemented in the JDFTx code53. The total energies, charged defect formation energies and geometry were evaluated at the PBE level54. Single-point calculations with k-point meshes of 2 × 2 × 1 and 3 × 3 × 1 were performed using hybrid exchange-correlation functional PBE0(α), where the mixing parameter α = 0.41 was determined by the generalized Koopmans’ condition as discussed in refs. 17,20. Moreover, we used the YAMBO code55 to perform many-body perturbation theory with the GW approximation to compute the quasi-particle correction using PBE0(α) eigenvalues and wavefunctions as the starting point. The RPA and BSE calculations were further solved on top of the GW approximation for the electron–hole interaction to investigate the optical properties of the defects, including absorption spectra and radiative lifetime.

Thermodynamic charge transition levels and defect formation energy

The defect formation energy (FEq) was computed for the TiVV and MoVV defects following:

where Eq is the total energy of the defect system with charge q, Epst is the total energy of the pristine system, μi and ΔNi are the chemical potential and change in the number of atomic species i, and εF is the Fermi energy. A charged defect correction Δq was computed for charged cell calculations by employing the techniques developed in refs. 15,51. The chemical potential references are computed as \({\mu }_{{\mathrm {Ti}}}={E}_{{\mathrm {Ti}}}^{{\mathrm {bulk}}}\) (total energy of bulk Ti), \({\mu }_{{\mathrm {Mo}}}={E}_{{\mathrm {Mo}}}^{{\mathrm {bulk}}}\) (total energy of bulk Mo), \({\mu }_{{\mathrm {BN}}}={E}_{{\mathrm {BN}}}^{{\mathrm {ML}}}\) (total energy of monolayer h-BN). Meanwhile the corresponding charge transition levels of defects can be obtained from the value of εF where the stable charge state transitions from q to \(q^{\prime}\).

Zero-field splitting

The first-order ZFS due to spin–spin interactions was computed for the dipole–dipole interactions of the electron spin:

Here, μ0 is the magnetic permeability of vacuum, ge is the electron gyromagnetic ratio, \({\hbar}\) is the Planck’s constant, s1, s2 is the spin of first and second electron, respectively, and r is the displacement vector between these two electron. The spatial and spin dependence can be separated by introducing the effective total spin S = ∑isi. This yields a Hamiltonian of the form \({H}_{{\mathrm {ss}}}={{\bf{S}}}^{{\mathrm {T}}}\hat{{\bf{D}}}{\bf{S}}\), which introduces the traceless ZFS tensor \(\hat{{\bf{D}}}\). It is common to consider the axial and rhombic ZFS parameters D and E which can be acquired from the \(\hat{{\bf{D}}}\) tensor:

Following the formalism of Rayson et al. 31, the ZFS tensor \(\hat{{\bf{D}}}\) can be computed with periodic boundary conditions as

Here the summation on pairs of i, j runs over all occupied spin-up and spin-down states, with χij taking the value +1 for parallel spin and −1 for anti-parallel spin, and Ψij(r1, r2) is a two-particle Slater determinant constructed from the Kohn–Sham wavefunctions of the ith and jth states. This procedure was implemented as a post-processing code interfaced with Quantum ESPRESSO. To verify our implementation is accurate, we computed the ZFS of the NV center in diamond which has a well-established result. Using ONCV pseudopotentials, we obtained a ZFS of 3.0 GHz for NV center, in perfect agreement with previous reported results29. For heavy elements such as transition metals, spin–orbit (SO) coupling can have substantial contribution to ZFS. Here, we also computed the SO contribution of the ZFS as implemented in the ORCA code56,57 (additional details can be found in Supplementary Note 10, Fig. 12, and Table 6).

Radiative recombination

In order to quantitatively study radiative processes, we computed the radiative rate ΓR from Fermi’s Golden Rule and considered the excitonic effects by solving BSE58:

Here, the radiative recombination rate is computed between the ground state G and the two-particle excited state S(Qex), \({1}_{{q}_{L},\lambda }\) and 0 denote the presence and absence of a photon, HR is the electron–photon coupling (electromagnetic) Hamiltonian, E(Qex) is the exciton energy, and c is the speed of light. The summation indices in Eq. (8) run over all possible wavevector (qL) and polarization (λ) of the photon. Following the approach described in ref. 58, the radiative rate (inverse of radiative lifetime τR) in SI unit at zero temperature can be computed for isolated defect–defect transitions as

where e is the charge of an electron, ϵ0 is vacuum permittivity, E0 is the exciton energy at Qex = 0, nD is the reflective index of the host material and \({\mu }_{{\mathrm {e-h}}}^{2}\) is the modulus square of exciton dipole moment with length2 unit. Note that Eq. (9) considers defect–defect transitions in the dilute limit; therefore the lifetime formula for zero-dimensional systems embedded in a host material is used8,59 (also considering nD is unity in isolated 2D systems at the long-wavelength limit). We did not consider the radiative lifetime of TiVV defect at a finite temperature because the first and second excitation energy separation is much larger than kT. Therefore a thermal average of the first and higher excited states is not necessary and the first excited state radiative lifetime is nearly the same at 10 K as zero temperature.

Phonon-assisted nonradiative recombination

In this work, we compute the phonon-assisted nonradiative recombination rate via a Fermi’s golden rule approach:

Here, ΓNR is the nonradiative recombination rate between electron state i in phonon state n and electron state f in phonon state m, pin is the thermal probability distribution of the initial state \(\left|{\mathrm {in}}\right\rangle\), He−ph is the electron–phonon coupling Hamiltonian, g is the degeneracy factor and Ein is the energy of vibronic state \(\left|{\mathrm {in}}\right\rangle\). Within the static coupling and one-dimensional (1D) effective phonon approximations, the nonradiative recombination can be reduced to:

Here, the static coupling approximation naturally separates the nonradiative recombination rate into phonon and electronic terms, Xif and Wif, respectively. The 1D phonon approximation introduces a generalized coordinate Q, with effective frequency ωi and ωf. The phonon overlap in Eq. (12) can be computed using the quantum harmonic oscillator wavefunctions with Q−Qa from the configuration diagram (Fig. 5). Meanwhile the electronic overlap in Eq. (13) is computed by finite difference using the Kohn–Sham orbitals from DFT at the Γ point. The nonradiative lifetime τNR is given by taking the inverse of the rate ΓNR. Supercell convergence of phonon-assisted nonradiative lifetime is shown in Supplementary Note 11 and Table 7. We validated the 1D effective phonon approximation by comparing the Huang–Rhys factor with the full phonon calculations in Supplementary Table 8.

SOC constant

SOC can entangle triplet and singlet states yielding the possibility for a spin–flip transition. The SOC operator is given to zero-order by60

where c is the speed of light, me is the mass of an electron, p and S are the momentum and spin of electron i and V is the nuclear potential energy. The spin–orbit interaction can be rewritten in terms of the angular momentum L and the SOC strength λ as60

where λ⊥ and λz denote the non-axial and axial SOC strength, respectively. The SOC strength was computed for the TiVV and MoVV defect in h-BN using the ORCA code by TD-DFT56,61. More computational details can be found in Supplementary Note 10.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study and the code for the first-principles methods proposed in this study are available from the corresponding author (Yuan Ping) upon reasonable request.

References

Koehl, W. F., Buckley, B. B., Heremans, F. J., Calusine, G. & Awschalom, D. D. Room temperature coherent control of defect spin qubits in silicon carbide. Nature 479, 84–87 (2011).

Weber, J. et al. Quantum computing with defects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8513–8518 (2010).

Liu, X. & Hersam, M. C. 2D materials for quantum information science. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 669–684 (2019).

Aharonovich, I. & Toth, M. Quantum emitters in two dimensions. Science 358, 170–171 (2017).

Mendelson, N., Doherty, M., Toth, M., Aharonovich, I. & Tran, T. T. Strain-induced modification of the optical characteristics of quantum emitters in hexagonal boron nitride. Adv. Mater. 32, 1908316 (2020).

Feldman, M. A. et al. Phonon-induced multicolor correlations in hBN single-photon emitters. Phys. Rev. B 99, 020101 (2019).

Yim, D., Yu, M., Noh, G., Lee, J. & Seo, H. Polarization and localization of single-photon emitters in hexagonal boron nitride wrinkles. ACS Appl. Mater. Int. 12, 36362–36369 (2020).

Mackoit-Sinkevičienė, M., Maciaszek, M., Van de Walle, C. G. & Alkauskas, A. Carbon dimer defect as a source of the 4.1 eV luminescence in hexagonal boron nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 212101 (2019).

Kianinia, M., White, S., Fröch, J. E., Bradac, C. & Aharonovich, I. Generation of spin defects in hexagonal boron nitride. ACS Photonics 7, 2147–2152 (2020).

Turiansky, M., Alkauskas, A. & Walle, C. Spinning up quantum defects in 2D materials. Nat. Mater. 19, 487–489 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Nonmagnetic quantum emitters in boron nitride with ultranarrow and sideband-free emission spectra. ACS Nano 11, 6652–6660 (2017).

Ivády, V., Abrikosov, I. A. & Gali, A. First principles calculation of spin-related quantities for point defect qubit research. npj Comput. Mater. 4, 1–13 (2018).

Komsa, H.-P., Berseneva, N., Krasheninnikov, A. V. & Nieminen, R. M. Charged point defects in the flatland: accurate formation energy calculations in two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031044 (2014).

Wang, D. et al. Determination of formation and ionization energies of charged defects in two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 196801 (2015).

Wu, F., Galatas, A., Sundararaman, R., Rocca, D. & Ping, Y. First-principles engineering of charged defects for two-dimensional quantum technologies. Phys. Rev. Mater. 1, 071001 (2017).

Govoni, M. & Galli, G. Large scale GW calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 2680–2696 (2015).

Smart, T. J., Wu, F., Govoni, M. & Ping, Y. Fundamental principles for calculating charged defect ionization energies in ultrathin two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 124002 (2018).

Nguyen, N. L., Colonna, N., Ferretti, A. & Marzari, N. Koopmans-compliant spectral functionals for extended systems. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021051 (2018).

Weng, M., Li, S., Zheng, J., Pan, F. & Wang, L.-W. Wannier Koopmans method calculations of 2D material band gaps. J. Chem. Phys. Lett. 9, 281–285 (2018).

Miceli, G., Chen, W., Reshetnyak, I. & Pasquarello, A. Nonempirical hybrid functionals for band gaps and polaronic distortions in solids. Phys. Rev. B 97, 121112 (2018).

Refaely-Abramson, S., Qiu, D. Y., Louie, S. G. & Neaton, J. B. Defect-induced modification of low-lying excitons and valley selectivity in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 167402 (2018).

Gao, S., Chen, H.-Y., Bernardi, M. Radiative properties and excitons of candidate defect emitters in hexagonal boron nitride. Preprint at arXiv:2007.10547 (2020).

Xu, J., Habib, A., Kumar, S., Wu, F., Sundararaman, R. & Ping, Y. Spin-phonon relaxation from a universal ab initio density-matrix approach. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–10 (2020).

Seo, H., Falk, A. L., Klimov, P. V., Miao, K. C., Galli, G. & Awschalom, D. D. Quantum decoherence dynamics of divacancy spins in silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–9 (2016).

Ye, M., Seo, H. & Galli, G. Spin coherence in two-dimensional materials. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 1–6 (2019).

Wu, F., Smart, T. J., Xu, J. & Ping, Y. Carrier recombination mechanism at defects in wide band gap two-dimensional materials from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 100, 081407 (2019).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. Ab initio calculation of spin–orbit coupling for an NV center in diamond exhibiting dynamic Jahn–Teller effect. Phys. Rev. B 96, 081115 (2017).

Gottscholl, A. et al. Initialization and read-out of intrinsic spin defects in a van der Waals crystal at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 19, 540–545 (2020).

Seo, H., Ma, H., Govoni, M. & Galli, G. Designing defect-based qubit candidates in wide-gap binary semiconductors for solid-state quantum technologies. Phys. Rev. Mater. 1, 075002 (2017).

Turiansky, M. E., Alkauskas, A., Bassett, L. C. & Walle, C. G. Dangling bonds in hexagonal boron nitride as single-photon emitters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 127401 (2019).

Rayson, M. & Briddon, P. First principles method for the calculation of zero-field splitting tensors in periodic systems. Phys. Rev. B 77, 035119 (2008).

Zolnhofer, E. M. et al. Electronic structure and magnetic properties of a titanium (II) coordination complex. Inorg. Chem. 59, 6187–6201 (2020).

Tran, T. T. et al. Robust multicolor single photon emission from point defects in hexagonal boron nitride. ACS Nano 10, 7331–7338 (2016).

Schell, A. W., Takashima, H., Tran, T. T., Aharonovich, I. & Takeuchi, S. Coupling quantum emitters in 2D materials with tapered fibers. ACS Photonics 4, 761–767 (2017).

Ahmadpour Monazam, M. R., Ludacka, U., Komsa, H.-P. & Kotakoski, J. Substitutional Si impurities in monolayer hexagonal boron nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 071604 (2019).

Sajid, A. & Thygesen, K. S. VNCB defect as source of single photon emission from hexagonal boron nitride. 2D Mater. 7, 031007 (2020).

Fuchs, F., Bechstedt, F., Shishkin, M. & Kresse, G. Quasiparticle band structure based on a generalized Kohn–Sham scheme. Phys. Rev. B 76, 115109 (2007).

Bechstedt, F. Many-Body Approach to Electronic Excitations (Springer-Verlag, 2016).

Ping, Y., Rocca, D. & Galli, G. Electronic excitations in light absorbers for photoelectrochemical energy conversion: first principles calculations based on many body perturbation theory. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 2437–2469 (2013).

Rocca, D., Ping, Y., Gebauer, R. & Galli, G. Solution of the Bethe–Salpeter equation without empty electronic states: application to the absorption spectra of bulk systems. Phys. Rev. B 85, 045116 (2012).

Ping, Y., Rocca, D., Lu, D. & Galli, G. Ab initio calculations of absorption spectra of semiconducting nanowires within many-body perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 85, 035316 (2012).

Ping, Y., Rocca, D. & Galli, G. Optical properties of tungsten trioxide from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 87, 165203 (2013).

Hours, J., Senellart, P., Peter, E., Cavanna, A. & Bloch, J. Exciton radiative lifetime controlled by the lateral confinement energy in a single quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 71, 161306 (2005).

Van de Walle, C. G. & Neugebauer, J. First-principles calculations for defects and impurities: applications to III-nitrides. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 3851–3879 (2004).

Goldman, M. L. et al. Phonon-induced population dynamics and intersystem crossing in nitrogen-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 145502 (2015).

Bassett, L. C. et al. Ultrafast optical control of orbital and spin dynamics in a solid-state defect. Science 345, 1333–1337 (2014).

Kim, S. et al. Photonic crystal cavities from hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–8 (2018).

Zhong, T. et al. Optically addressing single rare-earth ions in a nanophotonic cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 183603 (2018).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Hamann, D. R. Optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085117 (2013).

Sundararaman, R. & Ping, Y. First-principles electrostatic potentials for reliable alignment at interfaces and defects. J. Chem. Phys. 146, 104109 (2017).

Wang, D. & Sundararaman, R. Layer dependence of defect charge transition levels in two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. B 101, 054103 (2020).

Sundararaman, R., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Schwarz, K. A., Gunceler, D., Ozhabes, Y. & Arias, T. JDFTx: software for joint density-functional theory. SoftwareX 6, 278–284 (2017).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Marini, A., Hogan, C., Grüning, M. & Varsano, D. Yambo: an ab initio tool for excited state calculations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 1392–1403 (2009).

Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2, 73–78 (2012).

Neese, F. Calculation of the zero-field splitting tensor on the basis of hybrid density functional and Hartree–Fock theory. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 164112 (2007).

Wu, F., Rocca, D. & Ping, Y. Dimensionality and anisotropicity dependence of radiative recombination in nanostructured phosphorene. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 12891–12897 (2019).

Gupta, S., Yang, J.-H. & Yakobson, B. I. Two-level quantum systems in two-dimensional materials for single photon emission. Nano Lett. 19, 408–414 (2018).

Maze, J. R. et al. Properties of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond: the group theoretic approach. N. J. Phys. 13, 025025 (2011).

de Souza, B., Farias, G., Neese, F. & Izsák, R. Predicting phosphorescence rates of light organic molecules using time-dependent density functional theory and the path integral approach to dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 1896–1904 (2019).

Towns, J. et al. XSEDE: accelerating scientific discovery. Comput. Sci. Eng. 16, 62–74 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Susumu Takahashi for helpful discussions. This work is supported by the National Science Foundation under grant nos. DMR-1760260, DMR-1956015, and DMR-1747426. Part of this work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. T.J.S. acknowledges the LLNL Graduate Research Scholar Program and funding support from LLNL LDRD 20-SI-004. This research used resources of the Scientific Data and Computing center, a component of the Computational Science Initiative, at Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704, the lux supercomputer at UC Santa Cruz, funded by NSF MRI grant AST 1828315, the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) which is supported by National Science Foundation Grant No. ACI-154856262.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.P. established the theoretical models and supervised the project, T.J.S. and K.L. performed the calculations and data analysis, Y.P. and J.X. discussed the results, and all authors participated in the writing of this paper. T.J.S. and K.L. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smart, T.J., Li, K., Xu, J. et al. Intersystem crossing and exciton–defect coupling of spin defects in hexagonal boron nitride. npj Comput Mater 7, 59 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00525-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00525-5

This article is cited by

-

Coherent control of an ultrabright single spin in hexagonal boron nitride at room temperature

Nature Communications (2023)

-

First-principles theory of extending the spin qubit coherence time in hexagonal boron nitride

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022)

-

Spin-defect qubits in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides operating at telecom wavelengths

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Nuclear spin polarization and control in hexagonal boron nitride

Nature Materials (2022)

-

Transition metal impurities in silicon: computational search for a semiconductor qubit

npj Computational Materials (2022)