Abstract

Quantum mechanical simulations that include the effects of the liquid environment are highly relevant for the characterization of solid-liquid interfaces, which is crucial for the design of a wide range of devices. In this work we present a rigorous and systematic study of the band alignment of semiconductors in aqueous solutions by contrasting a range of hybrid explicit/implicit models against explicit atomistic simulations based on density-functional theory. We find that consistent results are obtained provided that the first solvation shell is treated explicitly. Interestingly, the first molecular layer of explicit water is only relevant for the pristine surfaces without dissociatively adsorbed water, hinting at the importance of saturating the surface with quantum mechanical bonds. By referencing the averaged electrostatic potentials of explicit and implicit water against vacuum, we provide absolute alignments, finding maximal differences of only \(\sim\) 0.1–0.2 V. Furthermore, the implicit reference potential is shown to exhibit an intrinsic offset of −0.33 V with respect to vacuum, which is traced back to the absence of an explicit water surface in the implicit model. These results pave the way for accurate simulations of solid-liquid interfaces using minimalistic explicit/implicit models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atomistic insight into the structure, composition and properties of solid-liquid interfaces is paramount for our understanding of the stability or performance of materials in many technological devices, such as chemical sensors, batteries, or fuel cells. Very often, such detailed knowledge can only be obtained from atomistic simulations or from a combination of theory and experiments (e.g., interpretation of spectroscopic measurements). Accounting for the presence of the liquid environment introduces significant challenges for such simulations, due to the large compositional and configurational space, in particular for electrochemical solid-liquid interfaces, where the stability of an interface composition is also influenced by the energetics of the long-range space-charge layers in the electrolyte over distances that are often out of reach for purely atomistic interface models.1,2

Recently, several studies have shown that coupling density-functional theory (DFT) to implicit solvation models can successfully mimic solvation-related effects.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 In these cases, the explicit electrolyte solution (e.g., water with ions) is substituted by a mean-field description of the solvent, where the liquid is modelled via a polarizable continuum or via joint density-functional theory.3,4,6,7,8,9 Computational costs are highly reduced not only because of smaller quantum mechanical systems but also because thermodynamic averaging of the liquid degrees of freedom is substituted by the response of the continuum model. Reasonable agreement between implicit descriptions of water and experiment is typically found for simulations of metallic slabs with respect to interfacial structure, capacitance, potential of zero charge, and interface energetics,1,4,5,6,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 which is related to limited water ordering for ambient temperatures on metals.18,19,20 For multicomponent semiconductor-water interfaces, on the other hand, rather strong surface-water interactions are more common21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 inducing very interface-specific properties of the solvation shell, where the general applicability of implicit solvation is yet to be tested.

In this work we test protocols to simulate accurately the band alignment of semiconductors leveraging implicit solvation models, and validate these against explicit simulations for the following semiconductors in water: (rutile) r-TiO\({}_{2}\)(110) and CdS(10\(\bar{1}\)0) with molecularly adsorbed water, GaN(10\(\bar{1}\)0) with dissociatively adsorbed water and (anatase) a-TiO\({}_{2}\)(101), GaAs(110) and GaP(110) with either of these two possibilities. All these terminations were previously found to be stable or meta-stable.29 We will show that it is necessary to describe the first solvation shell explicitly in order to capture interfacial potential drops accurately within an implicit model. Furthermore, we find that the electrostatic potential in the bulk of the implicit model is approximately 0.33 eV below the vacuum level for SCCS3 solvation, which can be explained by the absence of an explicit water surface in implicit models. The presented results provide a guideline for accurate simulations of electrochemical solid-liquid interfaces in implicit environments and new insights in the effects and properties of interfacial water layers and in the extent that they can be described by continuum models.

Results

Simulation protocol

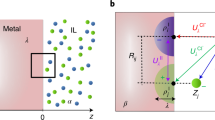

The approaches adopted for the determination of band alignment at semiconductor-water interfaces are schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. For both interface models, explicit (e) and implicit (i), we simulate an explicit semiconductor slab with potential adsorbates (e.g., explicit water molecules) immersed in an explicit aqueous or an implicit environment. In order to determine the band alignment on an absolute scale (e.g., w.r.t. vacuum or SHE) three potential offsets need to be known: They are marked as e1-e3/i1-i3 in Fig. 1 and correspond to the position of the bands, e.g., the bottom of the conduction band \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{c}}}\), w.r.t. the average bulk electrostatic potential \({V}_{{\rm{SC}}}\) (e1/i1), the alignment of \({V}_{{\rm{SC}}}\) w.r.t. the average bulk water potential \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}\) (e2/i2) and the position of \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}\) w.r.t. an absolute reference, most conveniently vacuum (e3/i3).

Schematics of band alignment at semiconductor-water interfaces using explicit and implicit descriptions for liquid water. Three separated calculations marked as e1–e3 and i1–i3 are needed to assess the band position on an absolute potential scale e.g., the vacuum level (gray dashed) including 1 the position of semiconductor band edges \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{C}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}\)/\({\epsilon }_{{\rm{C}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\) (brown lines) relative to the average potential in the bulk semiconductor, 2 the potential drop across the interfaces (green, black), and 3 the alignment of the average electrostatic potentials in the regions of water far away from the interfaces \({V}_{{\rm{w}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}\)/\({V}_{{\rm{w}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\) w.r.t. to vacuum

Whereas bulk simulations (e1/i1) are equivalent for explicit and implicit models, the alignment of \({V}_{{\rm{SC}}}\) with respect to the water average \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}\)(e2/i2) is different, due to the fact that the main electrostatic contribution of the average potential in explicit water—the quadrupole contribution 30,31—is missing in typical implicit models and due to different interface models used, e.g., with varying amount of explicitly treated interfacial water. Based on the properties of interfacial water from all-explicit ab-initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations (see below), we construct representative interface models with 0–3 explicit interfacial water layers by removal of appropriate H\({}_{2}\)O molecules from all-explicit AIMD trajectories. Subsequently, the potential offsets are determined by SCF calculations based on density-functional theory from the average electrostatic potential alignment \({V}_{{\rm{SC}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}\) w.r.t. \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}\) for the all-explicit model and \({V}_{{\rm{SC}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\) w.r.t. \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\) for the interfaces with reduced number of molecules embedded in an implicit environment. The final absolute alignment w.r.t. vacuum (e3/i3) is determined by studying explicit water slabs in vacuum and in implicit water. As we are in this work mainly interested in the accuracy of the alignment of electrostatic potentials which semilocal functionals can provide accurately,29 we restrict our analysis to the PBE32 exchange-correlation functional.

Interfacial water properties and interface model construction

Due to strong surface-water interactions for semiconductors the theoretical description of hydration traditionally discriminates between properties of primary and secondary hydration shells,23,25 where the latter is dominated by generic water-water interactions presumably amenable to continuum models. In contrast, the primary hydration shell (2–4 Å) with the first layer of adsorbed H\({}_{2}\)O is known to be very surface-specific and dominated by enthalpic interactions with the solid surface.22,24 In order to understand better the properties of interfacial water at the studied surfaces we performed a combined analysis of cumulative and molecule-specific descriptors, in particular the planar average of the water-related oxygen density (Fig. 2a) and a molecular entropy descriptor \(S\) (Fig. 2c), with:

The probabilities \({p}_{i}\) describe the sampling of the degrees of freedom of the H\({}_{2}\)O molecule and are estimated from histograms with bins \(i\) in the 6-dimensional molecular configuration space as visualized in Fig. 2b): the position in space r, the orientation of the molecular dipole \(\Omega\) and the rotational alignment \(\phi\) of the normal to the H–O–H plane. More technical details are given in section B of the Supplementary Information. \(S\) can be used to characterize the properties of water molecules, where small numerical values correspond to less mobile, more strongly bound H\({}_{2}\)O as it relates to narrower probability distributions \(p\). Due to limited simulation time scales (4–10 ps) no exchange of molecules between the individual water layers is observed.

Interfacial water properties for r-TiO\({}_{2}\) with molecularly adsorbed water. a Time-averaged oxygen density for water-related H\({}_{2}\)O. b Studied molecular degrees of freedom and marginal probability distributions \(p\) (histograms). Isotropic analysis of orientations was obtained by binning on a spherical surface, composed of 320 equal, equilateral triangles. c Individual and density-averaged molecular entropies \(S\) (see text for the definition) indicate distinct properties only for the first solvent shell

According to the molecular entropy-based analysis—as shown clearly for r-TiO\({}_{2}\) with molecularly adsorbed water in Fig. 2c)—only the molecules of the first water layer—if associated with the first, pronounced oxygen density peak (Fig. 2a)—show a distinctly different behavior than bulk-like water in the center of the water slab. H\({}_{2}\)O molecules in the additional layers are found to be not significantly different from bulk ones (Fig. 2c). Similar results are found for the other systems with the first density peak being significantly more pronounced for the pristine surfaces with molecularly adsorbed water indicating a qualitative difference in the interaction of passivated and unpassivated surfaces with the first molecular water layer (see section B of the Supplementary Information).

Based on these observations, we chose to define a water layer by the number of water molecules within the first density peak \({N}_{l}\) (for non-dissociated water). In this setup, \(n\) water layers correspond to the collection of the \(n\times {N}_{l}\) water molecules closest to the surface. This coincides mostly with minima in the observed O-density and is associated with a “discontinuous jump” in the average distance to the surface between the \(n\times {N}_{l}\)th and the \(n\times {N}_{l}+1\)st water molecule. We note in passing that—although well defined in the simulations here—a separation of the first water layer and the oxide surface can be ambiguous.26,27

Absolute level alignment

Step e1/i1

The position of conduction and valence band edges with respect to the average electrostatic potential are calculated for the bulk materials using the lattice constants of ref. 29 and reported in section C in the Supplementary Information.

Step e2/i2

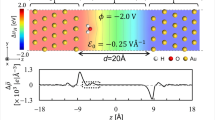

Averaged electrostatic potentials for a CdS \((10\bar10)\) slab in water are plotted in Fig. 3 where semi-transparent lines show the planar and ensemble average of the electrostatic potential and solid lines the macroscopic average, as determined from appropriately averaging the spatial variation of the potential (see Methods). \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}\) corresponds to the macroscopic average of the electrostatic potential in the center of water and \({V}_{{\rm{SC}}}\) to the average in the central 2 Å (marked with a cross in Fig. 3b). As remarked before, the average electrostatic potential inside bulk explicit water \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}\) is qualitatively and quantitatively different from an implicit electrostatic potential \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\) due to the presence/absence of electronic and nuclear charge density. However, if the different interface models considered here were equally suited to determine band positions, a consistent offset \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}={V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}-{V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\) should be observed across all surface terminations, when aligning corresponding systems with respect to the electrostatic potential in the center of the semiconductor slabs (cf. Fig. 3). Figure 4a summarizes the variation of the so-determined offset \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}={V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}-{V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\) for all considered systems, where a dissociated water layer is counted as an explicit layer. The bar heights indicate the estimated errors (see Methods). \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}\) is found to be nearly independent of the specific material and number of explicitly treated water molecules as long as one or more layers of water are treated explicitly. The average of \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}\) from the simulations with at least one explicit water layer is \(2.97\pm 0.05\) V; if the results with only one explicit layer are averaged (ignoring the results for a-TiO\({}_{2}\)(mol)) the offset is nearly equivalent with \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}=3.00\pm 0.10\) V. In contrast, calculations with zero explicit water give significantly different and inconsistent results.

a Planar ensemble average (semi-transparent) and macroscopic average (solid lines) of the electrostatic potential for CdS \((10\bar10)\) slabs in water. b Focus on the potential offsets. The macroscopic average \({V}_{{\rm{SC}}}\) in the central 2 Å of the slab is taken as a reference for determining the offset of the electrostatic potentials in the water regions \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}\) (implicit water: gray, red, orange with 0, 1, 2 explicit layers; explicit water: blue)

a Offset of implicit and explicit water potentials \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}={V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}-{V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\). \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}\) is nearly independent of the specific interface model (number of explicit water layers and material—see legend in panel b as long as one or more layers are treated explicitly. The structure of the first water layer is indicated by the labels mol (molecular water) and diss (dissociated water); the potential offset of −2.97 V is the average for results beyond 1 explicit layer. b Contributions to the potential offsets from the polarization potential of the implicit model. Bar heights indicate the 95% confidence interval. The gray horizontal bars are 0.4 V wide and are introduced as an aid to compare the different scales of panels a and b

It is worth noting that anatase TiO\({}_{2}\) with molecularly adsorbed water is a problematic case for the implicit procedure, with only few converging SCFs based on which we report averages, as already reported in ref. 33 and in private communications with other researchers. We speculate that this is due to surface Ti ions, whose electronic structure is extremely sensitive to the environment, making self-consistency more challenging. The reported results need to be taken with care due to possible biases for the small converged subset of calculations.

The fact that \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}\) shows negligible variations of \(\sim 0.2\) V (horizontal gray area in Fig. 4a) while the polarization potential contributions from the implicit model vary significantly (\(\sim 1\) V, Fig. 4b) indicates that the electrostatic response properties at the explicit/implicit interfaces are modelled accurately.

Step e3/i3

\({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}({\rm{abs}})\) on the absolute scale can be determined from the alignment of bulk explicit water with \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}({\rm{abs}})={V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}({\rm{abs}})-\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}\). \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}({\rm{abs}})\) is determined most conveniently from simulations of explicit water slabs in vacuum (trajectory taken from ref. 31, last 17 ps) and found to be −3.30 V here (Fig. 5a). The apparent difference to results from ref. 31 (−3.68 V) is due to different pseudopotentials used and the ENVIRON-specific electrostatic potentials with smeared nuclei (see Methods). A combination of the absolute alignment of explicit water \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}({\rm{abs}})=-3.30\) V with the above determined average \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}={V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}-{V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}=-2.97\) V yields an absolute alignment of the implicit potential \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}({\rm{abs}})=-0.33\) V.

a Absolute alignment of explicit water \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}\) from AIMD trajectories for a 25 Å thick water slab in vacuum (ref. 31). b The relative alignment of \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}\) for random water slabs (see text) in implicit solvation leads to a potential offset \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}={V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}-{V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}=-2.97\) V in perfect agreement with the results determined from averaging the offsets in Fig. 4. CB and VB edges are reported as averaged levels from the electronic states of the slab simulations and by introducing the respective bulk levels shifted to the ES average

It is important to note that this alignment is based on the well-behaved models whose explicit/implicit interface is in fact always a water/water interface. This points towards the offset \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}-{V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\) being a generic offset between implicit and explicit water. To test this hypothesis, we constructed random explicit/implicit water heterostructures with random interfaces from a bulk water AIMD trajectory (from ref. 31, 64 H\({}_{2}\)O molecules, V = (12.42 Å)\({}^{3}\), 13 ps). Random water slabs were constructed by choosing time steps at random, the x,y,z lattice directions shuffled and flipped at random and a vacuum layer of 12.42 Å introduced finally at a random position along the new z direction and respecting molecular integrity based on oxygen positions. As evidenced by the more detailed analysis presented in section E in the Supplementary Information, we tested also other construction protocols for water/water interfaces finding however very consistent results: the potential offset at explicit/implicit water/water interfaces is in average \(-2.97\pm 0.03\) V, which yields an absolute alignment of the implicit water potential of \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}({\rm{abs}})=-0.33\pm 0.04\) V w.r.t. vacuum (Fig. 5b) in perfect agreement with the result based on the semiconductor systems.

In order to understand better the origin of this offset in the implicit simulations we studied in addition the alignment of the random water slabs in vacuum. We find the electrostatic potential of random water slabs in vacuum slightly less negative as compared to the real water slab in agreement with the results of ref. 31 (\(-0.15\) V as compared to \(-0.25\pm 0.07\) V here). This offset is related to the specific, non-random ordering of water molecules at a water-vacuum interface and was referred to as the water surface dipole contribution in ref. 31. Along these lines of reasoning, we argue that the very similar observed absolute offset of \({V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}=-0.33\) V is mainly due to the absence of an explicit water-vacuum interface in the implicit simulations, which would contribute to the potential drop against vacuum.

Semiconductor level alignment w.r.t. SHE

The absolute alignments of the PBE band gaps are plotted in Fig. 6 for all interface models and materials based on above results and the SHE potential assumed at –4.44 V w.r.t. vacuum. Fig. 6 shows that apart from the case of a-TiO\({}_{2}\)(mol) where results might be unreliable, no significant increase in accuracy for the potential alignment is observed when including water layers beyond the first solvation shell. It should be mentioned that more realistic absolute band positions could be achieved by determining the bulk levels using an exchange-correlation functional that reproduces band gaps more accurately than PBE; this was, however, not the main point of interest here and thus not performed in this study.

Position of the PBE band gap for the studied systems w.r.t. to the SHE level (−4.44 V w.r.t. vacuum, potentials for hydrogen and oxygen evolution are plotted as red, dashed horizontal lines) with the number of explicitly treated water molecules increasing from left to right for each system. All-implicit and all-explicit results are indicated in red (hatched) and blue (dotted), respectively

Discussion

The findings of this work suggest that the absolute alignment of electrostatic potentials at semiconductor-water interfaces can be determined with an accuracy of \(\sim 0.1-0.2\) V across different materials and interface terminations using the SCCS implicit water model provided that the first water layer is simulated explicitly. On the other hand, simulations without inclusion of explicit water might very likely exhibit alignment errors of 1 V or more, which should be kept in mind when doing band alignment studies with implicit models. The importance of explicit interfacial water was also pointed out by others.34,35

We think the observed pattern that explicit water molecules need to be included particularly on top of unpassivated surfaces reflects a general principle that interfacial electrostatic potential drops are described correctly whenever the QM-implicit interface exhibits no unsaturated dangling bonds, which can influence close-by solvent molecules in a very specific way, not captured in implicit models. This agrees with the discussion in section C of the Supplementary Information which demonstrates clear differences in the properties for the first undissociated interfacial water layer on top of pristine surfaces and the H/OH terminated surfaces with dissociatively adsorbed water. On the other hand, the relative insensitivity of alignments with at the same time strongly varying implicit-model-related polarization contributions (Fig. 4) suggests that the SCCS model is indeed able to mimic accurately all generic solvent-related screening properties at explicit/implicit water interfaces.

The determined absolute alignment of the electrostatic potential inside the implicit region puts the SHE level at −4.11 eV w.r.t. the implicit level of the SCCS model, which allows an accurate definition of the absolute electrode potential in future simulations with implicit solvent regions as e.g., relevant in grand canonical simulations of electrochemical interfaces.1,36 The final step to develop an accurate simulation protocol for solid-liquid interfaces with implicit models will be to assess and validate ab-initio molecular dynamics simulations for mixed explicit/implicit models, which we will address in the future.

Methods

Computational setup

The fully equilibrated molecular dynamics trajectories used in this work were obtained in ref. 29 and ref. 31 by Born-Oppenheimer AIMD simulations in the NVT ensemble at 350 K with a time step of 0.5 fs and using a liquid water-adapted rVV10 functional,37 that accounts for nonlocal van der Waals interactions.38,39 For the nine selected interface terminations timeframes of 4–10 ps were carefully chosen such that no drifts of potential or change of interfacial composition are present in the trajectories and 100–150 snapshots randomly chosen from a subset of structures composed of each 50th MD step (\(\Delta t\) = 25 fs). DFT-based SCF calculations of fully explicit and explicit/implicit systems were performed using the ENVIRON40 module of Quantum ESPRESSO41 and PBE32 as exchange-correlation functional. As we are mainly interested here in demonstrating and testing the consistency of calculations for potential offsets at interfaces within implicit solvation models, we restrict the analysis to PBE, which underestimates band gaps but has been shown to reproduce potential offsets in good agreement with more advanced functionals and methods.29 We use pseudopotentials from the SSSP library42 (v0.7, PBE, efficiency) with wavefunction and density cutoffs of 45 and 360 Ry, respectively, and \(\Gamma\)-point-only sampling for the MD snapshots with a minute cold smearing43 of 0.001 Ry. The simulations were managed with the materials informatics infrastructure AiiDA.44 For the implicit model we use the SCCS formulation of the dielectric cavity3,45,46 as implemented in ENVIRON with the chosen meta-parameters tuned for correct solvation energetics of explicit H\({}_{2}\)O in the implicit model (env_static_permittivity = 78.3, env_pressure = −0.35 GPa, env_surface_tension = 50 dyn/cm, rhomax = 0.005 a.u., rhomin = 0.0001 a.u.). As recently shown,33 it is necessary to construct a solvent-aware SCCS boundary in order to prevent artificial dielectric pockets. Here, we use the optimized threshold value of 0.75 (see ref. 33). Calculations in slab geometry with implicit regions are typically non-symmetric which is why we applied the dipole correction and extended the list of calculations used for final analysis with mirror symmetric copies of structures and derived quantitities e.g., electrostatic potentials. It is important to note here that the charge density of atomic nuclei is smeared out in ENVIRON, which renormalizes the total quadrupole moment of the simulation cell and thus the average electrostatic potential. As a result, electrostatic potentials and electronic level positions are different from the standard Quantum ESPRESSO results, and the reported potential offsets (1–3) are ENVIRON-specific and not necessarily transferable, which is also true for results obtained with other codes or pseudopotentials. Yet, all observable quantities (e.g. band alignment of slabs in vacuum) will be consistent across codes and pseudopotentials when performed correctly (see also section A of the Supplementary Information). PBE band gaps and band alignment with respect to the average electrostatic potential were calculated for the bulk materials using the lattice constants of ref. 29 and a k-point sampling with Monkhorst-Pack meshes corresponding to a k-point distances of \(\le\)0.2 \({\mathring{\rm{A}} }^{-1}\)

Averaging of electrostatic potentials

Macroscopic averages of electrostatic potentials are determined by applying an appropriately normalized, top-hat smoothing filter with a width corresponding to the central semiconductor layer along the z direction to the planar ensemble average of the interfacial systems. Inside the water region the top-hat filter is switched to a smooth version (combination of Gaussian error functions) with individually tuned width and smoothness, to give nearly constant water electrostatic potentials in the center of the explicit water region. In this way both the potential in the center of the semiconductor and in the fully explicit water region can be accurately averaged as they become essentially flat. Individual error bars are approximated by 1.96 \(\times\) the standard error of the mean (95% confidence interval, with \({\rm{SEM}}=\sigma /\sqrt{n}\); \(\sigma\)= the standard deviation, \(n\)= number of structures). Errors of sums/differences (e.g., \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{W}}}={V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{ex}}}-{V}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{im}}}\)) are approximated by the root of the sum of squared individual errors. See also section D in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The AIMD trajectories used in this work are available via the Materials Cloud data repository (https://archive.materialscloud.org/), under following DOIs https://doi.org/10.24435/materialscloud:2019.0029/v1 and https://doi.org/10.24435/materialscloud:2019.0030/v1.

References

Hörmann, N. G., Andreussi, O. & Marzari, N. Grand canonical simulations of electrochemical interfaces in implicit solvation models. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 041730 (2019).

Nattino, F., Truscott, M., Marzari, N. & Andreussi, O. Continuum models of the electrochemical diffuse layer in electronic-structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 041722 (2019).

Andreussi, O., Dabo, I. & Marzari, N. Revised self-consistent continuum solvation in electronic-structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 064102 (2012).

Letchworth-Weaver, K. & Arias, T. A. Joint density functional theory of the electrode-electrolyte interface: application to fixed electrode potentials, interfacial capacitances, and potentials of zero charge. Phys. Rev. B 86, 075140 (2012).

Bonnet, N. & Marzari, N. First-principles prediction of the equilibrium shape of nanoparticles under realistic electrochemical conditions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 086104 (2013).

Mathew, K., Sundararaman, R., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Arias, T. A. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit solvation model for density-functional study of nanocrystal surfaces and reaction pathways. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 084106 (2014).

Ringe, S., Oberhofer, H. & Reuter, K. Transferable ionic parameters for first-principles Poisson-Boltzmann solvation calculations: Neutral solutes in aqueous monovalent salt solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 146, 134103 (2017).

Jinnouchi, R. & Anderson, A. B. Electronic structure calculations of liquid-solid interfaces: Combination of density functional theory and modified poisson-boltzmann theory. Phys. Rev. B 77, 245417 (2008).

Fisicaro, G., Genovese, L., Andreussi, O., Marzari, N. & Goedecker, S. A generalized Poisson and Poisson-Boltzmann solver for electrostatic environments. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 014103 (2016).

Dabo, I., Cancès, E., Li, Y. L. & Marzari, N. Towards First-principles Electrochemistry. arXiv 0901.0096 (2008).

Dabo, I., Li, Y., Bonnet, N. & Marzari, N. in Ab Initio Electrochemical Properties of Electrode Surfaces ch. 13, 415–431 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).

Sakong, S., Naderian, M., Mathew, K., Hennig, R. G. & Groß, A. Density functional theory study of the electrochemical interface between a pt electrode and an aqueous electrolyte using an implicit solvent method. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 234107 (2015).

Sakong, S., Forster-Tonigold, K. & Groß, A. The structure of water at a Pt(111) electrode and the potential of zero charge studied from first principles. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 194701 (2016).

Hansen, M. H. & Rossmeisl, J. ph in grand canonical statistics of an electrochemical interface. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 29135–29143 (2016).

Sundararaman, R. & Schwarz, K. Evaluating continuum solvation models for the electrode-electrolyte interface: Challenges and strategies for improvement. J. Chem. Phys. 146, 084111 (2017).

Huang, J. et al. Potential-induced nanoclustering of metallic catalysts during electrochemical co2 reduction. Nat. Commun. 9, 3117 (2018).

Gauthier, J. A. et al. Challenges in modeling electrochemical reaction energetics with polarizable continuum models. ACS Catal. 9, 920–931 (2019).

Schnur, S. & Groß, A. Properties of metal-water interfaces studied from first principles. N. J. Phys. 11, 125003 (2009).

Groß, A. et al. Water structures at metal electrodes studied by ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. J. Electrochem. Soc. 161, 3015–3020 (2014).

Biswas, R. & Bagchi, B. Anomalous water dynamics at surfaces and interfaces: synergistic effects of confinement and surface interactions. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30, 013001 (2018).

Kerisit, S., Cooke, D. J., Spagnoli, D. & Parker, S. C. Molecular dynamics simulations of the interactions between water and inorganic solids. J. Mater. Chem. 15, 1454–1462 (2005).

Feibelman, P. J. The first wetting layer on a solid. Phys. Today 63, 34–39 (2010).

Zemb, T. & Parsegian, V. A. Editorial overview: hydration forces. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 16, 515–516 (2011).

Parsegian, V. & Zemb, T. Hydration forces: observations, explanations, expectations, questions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 16, 618–624 (2011).

Björneholm, O. et al. Water at interfaces. Chem. Rev. 116, 7698–7726 (2016).

McBriarty, M. E. et al. Dynamic stabilization of metal oxide-water interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2581–2584 (2017).

McBriarty, M. E., Stubbs, J. E., Eng, P. J. & Rosso, K. M. Electrochemical interfaces: Potential-specific structure at the hematite-electrolyte interface. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1870054 (2018).

Monroe, J. I. & Shell, M. S. Computational discovery of chemically patterned surfaces that effect unique hydration water dynamics. PNAS 115, 8093–8098 (2018).

Guo, Z., Ambrosio, F., Chen, W., Gono, P. & Pasquarello, A. Alignment of redox levels at semiconductor-water interfaces. Chem. Mater. 30, 94–111 (2018).

Leung, K. Surface potential at the air-water interface computed using density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 496–499 (2010).

Ambrosio, F., Guo, Z. & Pasquarello, A. Absolute energy levels of liquid water. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 3212–3216 (2018).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Andreussi, O. et al. Solvent-aware interfaces in continuum solvation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 1996–2009 (2019).

Ping, Y., Sundararaman, R. & Goddard, W. A. III Solvation effects on the band edge positions of photocatalysts from first principles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 30499–30509 (2015).

Blumenthal, L., Kahk, J. M., Sundararaman, R., Tangney, P. & Lischner, J. Energy level alignment at semiconductor-water interfaces from atomistic and continuum solvation models. RSC Adv. 7, 43660–43670 (2017).

Sundararaman, R., Goddard, W. A. & Arias, T. A. Grand canonical electronic density-functional theory: algorithms and applications to electrochemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 146, 114104 (2017).

Miceli, G., deGironcoli, S. & Pasquarello, A. Isobaric first-principles molecular dynamics of liquid water with nonlocal van der Waals interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 034501 (2015).

Vydrov, O. A. & Van Voorhis, T. Nonlocal van der Waals density functional: the simpler the better. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 244103 (2010).

Sabatini, R., Gorni, T. & deGironcoli, S. Nonlocal van der Waals density functional made simple and efficient. Phys. Rev. B 87, 041108 (2013).

ENVIRON package. https://gitlab.com/olivieroandreussi/Environ.

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Prandini, G., Marrazzo, A., Castelli, I. E., Mounet, N. & Marzari, N. Precision and efficiency in solid-state pseudopotential calculations. npj Comput. Mater. 4, 72 (2018).

Marzari, N., Vanderbilt, D., DeVita, A. & Payne, M. C. Thermal contraction and disordering of the Al(110) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 3296–3299 (1999).

Pizzi, G., Cepellotti, A., Sabatini, R., Marzari, N. & Kozinsky, B. Aiida: automated interactive infrastructure and database for computational science. Comput. Mater. Sci. 111, 218–230 (2016).

Dupont, C., Andreussi, O. & Marzari, N. Self-consistent continuum solvation (SCCS): the case of charged systems. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 214110 (2013).

Andreussi, O. & Marzari, N. Electrostatics of solvated systems in periodic boundary conditions. Phys. Rev. B 90, 245101 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge partial financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) through the NCCR MARVEL and the EU through the MAX CoE for e-infrastructure. This work was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS) under project IDs s836 and s879 and the computing facilities of SCITAS, EPFL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.G.H. proposed the study, executed the presented simulations, and prepared the initial manuscript. Z.G. and F.A. performed the explicit AIMD simulations. N.G.H., O.A., A.P., and N.M. discussed the results and contributed to the writing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41524_2019_238_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Information: Absolute band alignment at semiconductor-water interfaces using explicit and implicit descriptions for liquid water

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hörmann, N.G., Guo, Z., Ambrosio, F. et al. Absolute band alignment at semiconductor-water interfaces using explicit and implicit descriptions for liquid water. npj Comput Mater 5, 100 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0238-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0238-4

This article is cited by

-

Electronic structure of aqueous two-dimensional photocatalyst

npj Computational Materials (2021)

-

Kinetic photovoltage along semiconductor-water interfaces

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Electrosorption at metal surfaces from first principles

npj Computational Materials (2020)