Abstract

Spectroscopy is a widely used experimental technique, and enhancing its efficiency can have a strong impact on materials research. We propose an adaptive design for spectroscopy experiments that uses a machine learning technique to improve efficiency. We examined X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) spectroscopy for the applicability of a machine learning technique to spectroscopy. An XMCD spectrum was predicted by Gaussian process modelling with learning of an experimental spectrum using a limited number of observed data points. Adaptive sampling of data points with maximum variance of the predicted spectrum successfully reduced the total data points for the evaluation of magnetic moments while providing the required accuracy. The present method reduces the time and cost for XMCD spectroscopy and has potential applicability to various spectroscopies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spectroscopy (X-ray, optical, infra-red, electron, etc.) is a popular and important experimental technique for materials analyses and investigations on the fundamental properties of materials.1,2,3,4,5,6 Large amounts of samples and experimental data need to be measured and treated for materials research and development. Therefore, there is a strong demand for high-throughput measurement to reduce the time and cost of spectroscopy experiments. In a conventional spectroscopy experiment, a large amount of data points is usually measured with sufficient measurement time to obtain a spectrum with an adequate signal-to-noise ratio. Often, the quality of a spectrum is determined according to the experimenter’s experience.

Although there are single-shot spectroscopy experiments like wavelength-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy,7 many kinds of spectroscopy need point-by-point measurement with scanning energy or wavelength. One can not obtain whole spectrum until the end of the experiment in such sequential point-by-point measurement and one can obtain parameters by analysis as a post-process after the measurement. Modern experiments like scanning X-ray micro-spectroscopy takes relatively long measurement time per energy because it takes scanning image at each energy point.8 Therefore, an efficient measurement by reducing energy data points based on the intelligent design of experiments is needed. At present, regression models are used to realise precise predictions thanks to advances in machine learning techniques, and such techniques can be applied to the intelligent design of spectroscopy experiments.9,10

Machine learning techniques have recently been introduced to materials science.11 Materials informatics12 is regarded as the fourth paradigm in the field of materials science following the previous paradigms of experiment, theory, and computation.13 In materials informatics, statistics and/or machine learning techniques are necessary to derive or predict target data from big data in an efficient manner. Bayesian optimisation has been applied to the high-throughput prediction of new materials.14,15 However, this kind of sampling optimisation strategy has never been applied to spectroscopic measurement. Bayesian optimisation can be applied when an optimisation objective can be defined as a functional to be modelled. Because our aim in this study was to optimise the measurement strategy for approximating the spectrum, instead of a Bayesian optimisation in which the Gaussian process16 is used as a fundamental modelling tool, we utilised the Gaussian process and its predictive variance to design efficient measurement strategies. Gaussian process regression is also known as kriging and is used in geostatistics to predict a geographic surface from an interpolation of discrete observation data.17

Generally, a spectrum is represented as a nonlinear function of energy or wavelength. The Gaussian process is a generalised linear model that can approximate such nonlinear spectral shapes by linear regression in feature space. The Gaussian process predicts a spectrum by tuning hyper-parameters through the learning of previous data of the spectrum. Moreover, not only the expectation value of the prediction but also the variance can be evaluated. Thus, the certainty of the prediction can be evaluated, and the efficiency of the adaptive sampling of new data points can be optimised.

In order to assess its applicability to spectroscopy, we applied Gaussian process modelling to X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) spectroscopy. XMCD spectroscopy is an experimental technique for quantitatively evaluating the orbital and spin magnetic moments of a material.18,19,20 These magnetic moments are related to the quantities evaluated from the X-ray absorption spectrum (XAS) and XMCD spectrum based on magneto–optical sum rules.21,22,23 Thus, XMCD spectroscopy is suitable for the quantitative assessment of the performance of a spectrum predictor modelled with Gaussian process.

In this paper, we propose an adaptive design for XMCD spectroscopy experiments that uses a machine learning technique. The XMCD spectrum is predicted by Gaussian process modelling with learning of an experimental spectrum. Adaptive sampling reduces the total data points for the evaluation of magnetic moments while maintaining the required accuracy.

Results

Strategies for the adaptive design of an XMCD spectroscopy experiment

Figure 1 shows comparison between conventional XMCD experiment and the adaptively designed XMCD experiment. In a conventional XMCD experiment, measurement and analysis are independent. Therefore, one can evaluate the magnetic moments after the measurement. On the other hand, in an adaptively designed XMCD experiment, one can evaluate magnetic moments in sampling-by-sampling regime. First, initial data points are sampled to obtain an experimental discrete spectrum as the training data set. Next, a spectrum is continuously predicted by Gaussian process modelling fitted to the training data set. Then, magnetic moments are evaluated from the predicted XMCD and XAS spectra. The experiment is stopped if the values of the magnetic moments satisfy the convergence criterion. Otherwise, new data points are sampled, and the spectrum is predicted again. Note that no prior knowledge is included in the modelling.

Comparison between conventional XMCD experiment and the adaptively designed XMCD experiment. (left) Flowchart for conventional XMCD spectroscopy experiment. First, data points are sampled to obtain a spectrum for opposite directions of X-ray polarisations or magnetisation directions at each energy point. Next, magnetic moments are evaluated from the experimental spectra. (right) Flowchart for the adaptive design of the XMCD spectroscopy experiment. First, initial data points are sampled to obtain an experimental spectrum as the training data set for opposite directions of X-ray polarisations or magnetisation directions at each energy point. Next, the Gaussian process (GP) model predicts the spectra, and magnetic moments are evaluated from the predicted spectra. The convergence of values of the magnetic moments are checked in order to determine whether to sample new data points and return to predicting spectra or stop the experiment. We examined two and three options for sampling initial data points and selecting new sampling point, respectively

We used Sm M4,5 XMCD and XAS spectra of SmCo5 to assess the applicability of Gaussian process modelling. We examined two sampling conditions for the initial data points: (1) Equally sampled 30 data points from the pre-edge to the post-edge of the Sm M4,5 absorption edges (1060–1130 eV). (2) Intensively sampled 30 data points at the M5 and M4 peaks (15 data points for each); this is because the peak positions of a specific element are usually known beforehand.

We examined three methods for the selection of new sampling data points: (1) Sample the data point with maximum variance (max. var.) of the predicted spectrum, (2) random sampling, and (3) random sampling weighted with variance (i.e., a data point with large variance has a high possibility of being sampled). Hereafter, this sampling method is called ‘weighted sampling’. Note that random sampling and weighted sampling were examined 50 times with different random numbers and averaged for all examinations.

Magnetic moments should converge if the variation in the magnetic moments is less than 0.5% for five successive times. If the convergence criterion is not satisfied, a new sampling point is selected and sampled with the methods described above.

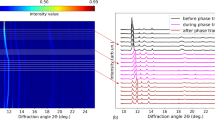

XMCD and XAS spectra measured in a conventional experiment

First, Fig. 2 shows the Sm M4,5 XMCD and XAS spectra of SmCo5 obtained in a conventional experiment. These spectra were obtained by counting transmitted X-rays through the specimen. In total, 216 data points were measured for the energy range of 1060–1130 eV. Both the XMCD and XAS spectra were similar to those of trivalent Sm ion that have been reported previously.24,25 To evaluate the magnetic moments by the magneto–optical sum rules, the integral values of the XMCD spectrum p, q and integral value of the XAS spectrum r need to be calculated. The red solid lines in Fig. 2 represent the energy-integration spectra for XMCD and XAS. The p value was taken at 1096 eV to be p = 0.39, and the q and r values were taken at 1130 eV to be q = 2.06 and r = 16.3, respectively. By applying the magneto–optical sum rules, we obtained the orbital magnetic moment mo = 2.27μB, spin magnetic moment ms = −2.34μB, and their ratio mo/ms = −0.97. We assumed the number of 4f holes to be n = 9 for the trivalent Sm ion. Note that the magnetic dipole moment is effectively included in ms. In this study, these values of magnetic moments were used as a reference for the optimisation by Gaussian process modelling.

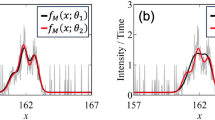

XMCD spectra predicted by the Gaussian process model

Figure 3a–f shows the typical XMCD spectra predicted by the Gaussian process model. The initial 30 data points were equally separated and artificially extracted from the experimental XMCD spectrum shown in Fig. 2a. The predicted spectra (blue solid curves) for different numbers of total energy points are shown for comparison. Variances in the predicted spectra (red solid curves) became large between the observed data points, as clearly shown in Fig. 3a. The data point with the maximum variance of the predicted spectrum was adaptively sampled. By increasing the observed data points, the total variance of the predicted spectra became smaller, and the spectral shape of the predicted spectrum became similar to that of the experimental spectrum.

a–f XMCD spectra predicted by the Gaussian process model with the equally separated initial data points (black filled circles in a) and maximum variance point sampling. Sm M4,5 XMCD spectra for a 30, b 35, c 40, d 50, e 60, and f 70 total data points. The black dashed and blue solid curves represent the true (experimental) spectrum and predicted spectrum by the GP model, respectively. The open circles represent observed data points. The red solid curves indicate the variance with the 95% confidence interval (±2σ) of the predicted spectrum. g–k Results for the adaptive design of the XMCD spectroscopy experiment where the initial data points had equal separation. g Orbital magnetic moment mo, h spin magnetic moment ms, and i their ratio mo/ms plotted as functions of the total data points. The red, blue, and green markers represent the methods for data point sampling: maximum variance (max. var.), random, and random sampling weighted by variance, respectively. The black solid and dashed lines represent the reference value and 5% deviations, respectively. j Total data points to convergence values of mo, ms, and mo/ms for different sampling methods. k Deviations of mo, ms, and mo/ms from their values in the conventional experiment

Figure 4a–f shows another example of the XMCD spectra predicted by the Gaussian process model. The initial 30 data points were intensively sampled around the main peaks. In Fig. 4a, the predicted spectrum approximates the experimental spectra very well for peak regions. However, the predicted spectrum largely deviates from the experimental spectra for non-peak regions and variance is very large. The total variance of the predicted spectra became smaller with increasing the data points, however the deviation from the experimental spectrum in non-peak regions is large even for 50 pts (Fig. 4d) as compared to that of the case of initial data points with equal separation (Fig. 3d).

a–f XMCD spectra predicted by the Gaussian process model with the initial data points intensively sampled around peaks (black filled circles in a) and maximum variance point sampling. Sm M4,5 XMCD spectra for a 30, b 35, c 40, d 50, e 60, and f 70 total data points. The black dashed and blue solid curves represent the true (experimental) spectrum and predicted spectrum by the GP model, respectively. The open circles represent observed data points. The red solid curves indicate the variance with the 95% confidence interval (±2σ) of the predicted spectrum. g–k Results for the adaptive design of the XMCD spectroscopy experiment with the initial data points intensively sampled around peaks. g Orbital magnetic moment mo, h spin magnetic moment ms, and i their ratio mo/ms plotted as functions of the total data points. The red, blue, and green markers represent the methods for data point sampling: maximum variance (max. var.), random, and random sampling weighted by variance, respectively. The black solid and dashed lines represent the reference value and 5% deviations, respectively. j Total data points to convergence values of mo, ms, and mo/ms for different sampling methods. k Deviations of mo, ms, and mo/ms from their values in the conventional experiment

Results for the adaptive design of the XMCD spectroscopy experiment

Figures 3g–k and 4g–k show the results for the adaptive design of the XMCD spectroscopy experiment. Figure 3g–i shows the results for the initial data points with equal separation. The orbital magnetic moment, spin magnetic moment, and their ratio from the predicted spectrum are plotted as functions of the total data points. True values for the magnetic moments and the ±5% errors are indicated by black solid and dashed lines, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3g, the orbital magnetic moment converged to the true value at around 40 total data points with maximum variance sampling. Random sampling showed poor convergence to the true value even with 100 total data points. Weighted sampling behaved halfway between maximum variance sampling and random sampling and showed good convergence to the true value. As shown in Fig. 3h, the spin magnetic moment almost fell within ±5% of the true value with the initial 30 data points. It showed moderate convergence to the true value as the number of data points was increased. As shown in Fig. 3i, the ratio between the orbital and spin magnetic moments had the same tendency as the orbital magnetic moment for different sampling methods. Maximum variance sampling rapidly converged to the true value around 40 data points. Figure 3j shows the total number of data points for the various sampling methods to satisfy the convergence criterion. All sampling methods satisfied the convergence criterion at about 50 points. Random sampling seemed to converge with the minimum number of data points for mo and mo/ms. However, the deviation of the converged value of the magnetic moment from the true value was very large compared to those of maximum variance sampling and weighted sampling, as shown in Fig. 3k.

Figure 4g–i shows the results for the initial data points with intensive sampling around peaks. As shown in Fig. 4g, the orbital magnetic moment was within ±5% of the true value with the initial 30 data points. However, the value was overestimated as the number of data points was increased with all sampling methods. The deviation from the true value was largest for maximum variance sampling at around 40–50 data points. As shown in Fig. 4h, the spin magnetic moment greatly deviated from the true value with the initial 30 data points. The value converged to the true value as the number of data points was increased. As shown in Fig. 4i, the orbital to spin magnetic moment ratio also greatly deviated from the true value with the initial 30 data points and converged as the number of data points was increased. As shown in Fig. 4j, the total number of data points for convergence was more than the initial data points with equal separation.

This comparison of the results revealed that Gaussian process modelling works well for initial data points with equal separation. Sampling data points with the maximum variance of a predicted spectrum results in the convergence of magnetic moments with the minimum number of total data points and good accuracy.

Validation of the present method

Gaussian process modelling was found to work well at approximating Sm M4,5 XMCD and XAS spectra with complex spectral shapes. To validate the method, we applied it to the Fe and Co L2,3 XMCD and XAS spectra of FeCo alloy. Those spectra were measured by total electron yield method. Measurement method and electron transition is totally different between previous Sm M4,5 and present Fe and Co L2,3 spectra. The results are shown in Fig. 5. The initial 10 data points were equally separated within the energy range of the Fe and Co L2,3 absorption edges, respectively. The overall trends for the magnetic moments versus the total number of data points were the same as those of Sm M4,5 XMCD. The maximum variance sampling converged to the magnetic moments with the minimum number of total data points and minimum deviation compared to the other sampling methods for Fe. Deviation from the true values for weighted sampling is smaller than max. var. sampling for Co. This is considered as the effect of the average of 50 trials. Thus, the present method also works well for the Fe and Co L2,3 XMCD spectra.

Results for the adaptive design of an XMCD spectroscopy experiment applied to a–e the Fe L2,3 and f–j the Co L2,3 XMCD spectra where the initial data points had equal separation. a,f Orbital magnetic moment mo, b,g spin magnetic moment ms, and c,h their ratio mo/ms plotted as functions of the total number of data points. The red, blue, and green markers represent the method for data point sampling: maximum variance (max. var.), random, and random sampling weighted by variance, respectively. The black solid and dashed lines represent the reference value and 5% deviations, respectively. d,i Total data points for the values of mo, ms, and mo/ms to converge with different sampling methods. e,j Deviations of mo, ms, and mo/ms from their values in the conventional experiment. Inset in b shows the Fe L2,3 XMCD spectrum with initial data points (black filled circles). The black dashed and blue solid curves represent the true (experimental) spectrum and predicted spectrum by the GP model, respectively. The red solid curves indicate the variance with the 95% confidence interval (±2σ) of the predicted spectrum

As described above, the present method is valid for XMCD spectra for completely different absorption edges, compounds, instruments, and measurement methods. Generally, we do not know the spectral shapes of X-ray absorption and XMCD spectra of unknown materials, however the method is useful to predict the magnetic moments with required accuracy. Note that the present method is not the method to predict detailed spectral shapes of X-ray absorption and XMCD spectra of unknown materials, but to predict magnetic moments with required accuracy under the reduced measurement time. In other words, magneto–optical sum rules are robust for fine structures of the spectra to evaluate the magnetic moments.

Selection of the correlation function

Choice of the correlation function is an essential issue in Gaussian process modelling. We examined exponential and Matérn correlation functions with various parameters as well as the Gaussian correlation functions, which we already shown the results above. We applied Gaussian process modelling with various correlation functions to the Sm M4,5 XMCD and XAS spectra. We tried the best method for initial sampling (i.e., equally separated data points) and adaptive sampling (i.e., sampling data points with maximum variance) for the exponential and Matérn correlation functions. As shown in Fig. 6, mo, ms, and mo/ms values converge to the true value by increase of total data points. Gaussian, exponential and Matérn correlation functions with k = 0.5 show similar tendency in particular for mo. However, convergence to the true value of Gaussian correlation function seems faster than other correlation functions for ms and mo/ms. On the other hand, Matérn correlation functions with k = 1, 1.5 and 2 deviates from true values in fewer data points and abruptly converges. Therefore, we concluded the Gaussian correlation function is the best for the present method.

Results for the adaptive design of an XMCD spectroscopy experiment for Sm M4,5 XMCD spectrum by the Gaussian process modelling with various correlation functions: Gaussian (same as in Fig. 3), exponential, and Matérn. a Orbital magnetic moment mo, b spin magnetic moment ms, and c their ratio mo/ms plotted as functions of the total number of data points. Initial data points are equally separated and adaptive sampling of the data point with the maximum variance was applied. Parameters are set to p = 1 for the exponential correlation function and k = 0.5,1,1.5,2 for the Matérn correlation function

Discussion

Generally, peaks are considered to be more important than non-peak regions of a spectrum. Modern XMCD experimental instruments allow intensive sampling of specific energy ranges; i.e., higher density around the peaks and lower density in non-peak regions. By considering such a situation, we examined the case when initial data points are intensively sampled at peaks. The convergence of the magnetic moments was worse than that of initial data points separated equally as shown in Fig. 4. This is because of the large variance in the non-peak regions of the predicted spectrum. Therefore, the equally separated sampling is better than the intensive sampling around the peaks, which is against our intuition, for the present method which predicts the spectra by Gaussian process modelling.

Gaussian process modelling has several favourable properties. First, under mild regularity conditions, the Gaussian process model asymptotically obtains an optimal functional relationship that minimises the gap between the true response y(x) and prediction \(\hat y(x)\). Second, when there are a finite number of observations as in real situations, the average of the squared error (i.e., generalisation error) between the true response and prediction by the Gaussian process model is known to show a roughly linear decrease for small n. As the number of observations is increased, the rate of decay of the generalisation error becomes slower than 1/n.26,27 This was also observed in our experimental results (not shown).

Gaussian process modelling offers accurate functional form estimation with point-wise confidence values. However, inference based on the Gaussian process requires storing and inverting the Gram matrix, which typically scales as O(n3). For large problems, storing and inverting a large-size matrix are prohibitive, and a large number of approximation methods have been developed to deal with this computational problem, such as the Nyström method.28 In our problem though, the number of energy points to be evaluated is 216 at most; hence, all of the computation can be done without resorting to approximation methods. If we use our proposed method for larger problems with many energy points, conventional approximation methods for the Gaussian process can be readily combined with our method to reduce the computational and storage costs.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the adaptive design of an XMCD spectroscopy experiment with Gaussian process modelling. The Gaussian process was found to successfully predict the nonlinear spectral shapes of the XMCD spectrum. Magnetic moments can be evaluated from the predicted spectra with the required level of accuracy. The present method reduces the total number of data points for measurement as well as the time and cost of an XMCD spectroscopy experiment. This method has potential applicability to various spectroscopy. It drastically reduces measurement time for point-by-point measurement, such as scanning transmission X-ray microscopy with scanning energy points around absorption edges.

Methods

XAS and XMCD experiments

Sm M4,5 XMCD and XAS spectra of SmCo5 were obtained by using a scanning transmission X-ray microscope (STXM)29 at the BL-13A of the Photon Factory, Institute of Materials Structure Science, High Energy Accelerator Research Organization, Japan. A SmCo5 specimen for the STXM experiment was prepared from a thermally demagnetised bulk material by using a micro-fabrication technique. In the STXM experiment at the Photon Factory, XMCD spectra are obtained as a difference of two X-ray absorption spectra for right-handed and left-handed elliptically polarised X-rays that are measured over the entire spectrum for fixed polarisation. Details of the STXM experiment are described in the literature.30 Fe and Co L2,3 XMCD and XAS spectra of FeCo alloy were measured at BL-14 of Hiroshima Synchrotron Radiation Center (HSRC), Hiroshima University, Japan.31 Spectra were obtained with the total electron yield method by measuring the sample drain current. In the XMCD experiment at HSRC, polarisation of the incident X-ray was fixed and the relative direction of the external magnetic field was switched parallel and antiparallel to the X-ray polarisation at each energy point. Details of the XMCD experiment at HSRC are described in the literature.32

Magneto–optical sum rules

The orbital magnetic moment (mo) and spin magnetic moment (ms) were calculated by applying the magneto–optical sum rules to the XMCD and XAS spectra. Experimentally obtained XMCD and XAS spectra were integrated along the energy axis to evaluate p, q, and r. p and q were obtained from the XMCD spectrum, and r was obtained from the XAS spectrum. The magneto–optical sum rules relate these values to the magnetic moments. For the 3d–4f transition (M4,5 edges) of rare earth elements such as Sm, the orbital sum rule is given as follows 21,22,24:

where mo is the orbital magnetic moment and μB and n are the Bohr magneton and number of holes in the 4f orbital, respectively. The spin sum rule for the 3d–4f transition is given as follows:

where ms is the spin magnetic moment and \(\left\langle {T_{\mathrm{z}}} \right\rangle\) is the expectation value of the magnetic dipole moment. For the magneto–optical sum rules for 2p–3d transition (L2,3 edges), see.23

Gaussian process for approximating continuous spectrum

We explain the Gaussian process modelling and how the relevant parameters are estimated below by using the observed data points. For details on Gaussian process modelling, see ref. 16. Our implementation of the proposed method is based on the R33 package GPfit.34 Let the i-th energy and corresponding output spectral be denoted by x i and y i = y(x i ), respectively. The observed data points are denoted by \(X = (x_1, \ldots ,x_n)^{\rm T} \in {\Bbb R}^n\), and the corresponding responses are denoted by Y = y(X) = (y1,…,y n )Τ. The relation between the energy and output (e.g., XAS or XMCD spectrum) is modelled as

where μ is the overall mean and z(x i ) is a Gaussian process with \({\Bbb E}[z(x_i)] = 0,{\mathrm{Var}}(z(x_i)) = \sigma ^2\), and \({\mathrm{Cov}}(z(x_i),z(x_j)) = \sigma ^2R_{ij}\). In the Gaussian processing model, y(X) is assumed to have a multivariate normal distribution \({\it{{\cal N}}}({\mathbf{1}}_n\mu ,\sigma ^2R)\), where 1 n is an n × 1 vector of all ones, and R is the correlation matrix with elements R ij . There were several choices for the correlation structure; we used the most popular Gaussian correlation function defined by

where \(\theta \in [0,\infty )\) is a hyper-parameter to be tuned. The maximum likelihood estimates of the mean and variance parameters are functions of the hyper-parameter θ and are obtained by using the observed data points X and responses Y as follows:

These estimates are plugged into the log-likelihood function of the Gaussian process model to estimate the hyper-parameter θ:

By using \(\hat \mu ,\hat \sigma\), and R (calculated using the optimised parameter \(\theta ^ \ast = {\mathrm{argmax}}_{\theta \in [0,\infty )}log(L_\theta )\)), the best predictor \(\hat y\) for a newly observed point \(x^ \ast\) is obtained as follows:

with the mean squared error

where r = (r1(x*),…,r n (x*))Τ and r i (x*) = Cor(z(x*),z(x i )). The mean squared error s2 is used as the criterion for selecting the next energy to be examined.

To optimise the hyper-parameter θ, we used a multi-start gradient ascent to maximise the likelihood. In our implementation, we randomly selected 200 starting points of the hyper-parameter and used the quasi-Newton method (L-BFGS-B algorithm) with 200 different initial points. Then, we chose the results with the maximum likelihood value.

In order to investigate the effect of the choice of the correlation function for Gaussian process modelling, we tried other correlation functions as shown below. One is an exponential correlation function

with p = 1. Note that the exponential correlation function with p = 2 is equivalent for the Gaussian correlation function. Another is a Matérn correlation function

where ν = (2k + 1)/2 with k = 0.5,1,1.5,2 and κ ν is the modified Bessel function of order ν.

Typical computational time for Gaussian process modelling of an XMCD spectrum in the present study is 0.03 to 0.2 s by using a laptop with a 3.3 GHz Intel Core i7 CPU.

Data availability

The data and codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Hollas, J. M. Modern Spectroscopy. (Wiley, West Sussex, 2004).

Stöhr, J. NEXAFS Spectroscopy. (Springer, Berlin, 1996).

Hüfner, S. Photoelectron Spectroscopy–Principles and Applications. (Springer, New York, 1995).

Stuart, B. H. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications. (Wiley, West Sussex, 2004).

Nasu, N. in Mössbauer Spectroscopy–Tutorial Book (eds Yoshida, Y. & Langouche, G.) (Springer, Heidelberg, 2013).

Egerton, R. F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope. (Springer, New York, 2011).

Matsushita, T. & Phizackerley, R. P. A fast X-ray absorption spectrometer for use with synchrotron radiation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 20, 2223–2228 (1981).

Hitchcock, A. P. in Handbook of Nanoscopy (eds Van Tendeloo, G., Van Dyck, D. & Pennycook, S. J.) (Wiley, Weinheim, 2012).

Mueller, T., Kusne, A. G. & Ramprasad, R. in Reviews in Computational Chemistry, Vol. 29 (eds Parrill, A. L. & Lipkowitz, K. B.) (Wiley, Hoboken, 2015).

Burnaex, E. & Panov, M. in Statistical Learning and Data Sciences (eds Gammerman, A., Vovk, V. & Papadopoulos, H.) (Springer, Cham, 2015).

Lookman, T. et al. in Information Science for Materials Discovery and Design (eds Lookman, T., Alexander, F. J. & Rajan, K.) (Springer, Cham, 2016).

Rajan, K. Materials informatics. Mater. Today 8, 38–45 (2005).

Agrawal, A. & Choudhary, A. N. Perspective: materials informatics and big data: realization of the ‘fourth paradigm’ of science in materials science. APL Mater. 4, 053208 (2016).

Seko, A., Maekawa, T., Tsuda, K. & Tanaka, I. Machine learning with systematic density-functional theory calculations: application to melting temperatures of single- and binary-component solids. Phys. Rev. B 89, 054303 (2014).

Seko, A. et al. Prediction of low-thermal-conductivity compounds with first-principles anharmonic lattice-dynamics calculations and Bayesian optimization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 205901 (2015).

Rasmussen, C. E. & Williams, C. K. I. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2006).

Oliver, M. A. Kriging: a method of interpolation for geographical information systems. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 4, 313–332 (1990).

Stöhr, J. & Siegmann, H. C. Magnetism—From Fundamentals to Nanoscale Dynamics (Springer, Berlin, 2006).

Stöhr, J. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy of transition metal thin films. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 75, 253–272 (1995).

van der Laan, G. & Figueroa, A. I. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism—a versatile tool to study magnetism. Coord. Chem. Rev. 277-278, 95–129 (2014).

Thole, B. T., Carra, P., Sette, F. & van der Laan, G. X-Ray circular dichroism as a probe of orbital magnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 1943–1946 (1992).

Carra, P., Thole, B. T., Altarelli, M. & Wang, X. X-ray circular dichroism and local magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 694–697 (1993).

Chen, C. T. et al. Experimental confirmation of the X-ray magnetic circular dichroism sum rules for iron and cobalt. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 152–155 (1995).

Qiao, S. et al. Direct evidence of ferromagnetism without net magnetization observed by x-ray magnetic circular dichroism. Phys. Rev. B 70, 134418 (2004).

Dhesi, S. S. et al. Spin- and orbital-moment compensation in the zero-moment ferromagnet Sm0.974Gd0.026Al2. Phys. Rev. B 82, 180402 (2010).

Williams, C. K. I. & Vivarelli, F. Upper and lower bounds on the learning curve for Gaussian processes. Mach. Learn. 40, 77–102 (2000).

Sollich, P. & Halees, A. Learning curves for Gaussian process regression: approximations and bounds. Neural Comput. 14, 1393–1428 (2002).

Williams, C. & Seeger, M. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 13 (eds Leen T. K., Dietterich, T. G. & Tresp, V.) (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2001).

Takeichi, Y. et al. Design and performance of a compact scanning transmission X-ray microscope at the Photon Factory. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 87, 013704 (2016).

Ueno, T., Hashimoto, A., Takeichi, Y. & Ono, K. Quantitative magnetic-moment mapping of a permanent-magnet material by X-ray magnetic circular dichroism nano-spectroscopy. AIP Adv. 7, 056804 (2017).

Sawada, M. et al. XMCD experimental station optimized for ultrathin magnetic films at HiSOR-BL14. AIP Conf. Proc. 1234, 939–942 (2010).

Ueno, T. et al. Coverage-dependent magnetic properties of Ni ultrathin films on Pd(001) investigated using X-ray magnetic circular dichroism. Appl. Phys. Express 7, 063006 (2014).

R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016) https://www.R-project.org/.

MacDonald, B., Ranjan, P. & Chipman, H. GPfit: an R package for fitting a Gaussian process model to deterministic simulator outputs. J. Stat. Softw. 64, 1–23 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Part of this work was supported by the Elements Strategy Initiative Center for Magnetic Materials (ESICMM) under the outsourcing project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. This work was supported in part by ‘Materials Research by Information Integration’ Initiative (MI2I) project of the Support Program for Starting Up Innovation Hub from Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST). The authors thank Shin-Etsu Chemical Co., Ltd., for providing SmCo5 material. T.U. thanks Prof. Yoshifumi Ueda for his support with the preparation of the FeCo sample. The STXM experiment was performed with the approval of the Photon Factory Program Advisory Committee (Proposal No. 2015MP004). The XAS and XMCD experiments were performed at HSRC with the approval of the Proposal Assessing Committee (Proposal No. 11-B-14). T.U. acknowledges the support of JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15K17458. H.H. is supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 16K16108 and 25120011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.U., H.H., and K.O. wrote the manuscript. T.U. and H.H. performed the computation of the Gaussian process modelling. T.U., A.H., Y.T., and K.O. performed the STXM experiment at the Photon Factory. T.U. and M.S. performed the XAS and XMCD experiments at HSRC. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ueno, T., Hino, H., Hashimoto, A. et al. Adaptive design of an X-ray magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy experiment with Gaussian process modelling. npj Comput Mater 4, 4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-017-0057-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-017-0057-4

This article is cited by

-

Bayesian active learning with model selection for spectral experiments

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Autonomous atomic Hamiltonian construction and active sampling of X-ray absorption spectroscopy by adversarial Bayesian optimization

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Active learning by query by committee with robust divergences

Information Geometry (2023)

-

Bayesian optimization with experimental failure for high-throughput materials growth

npj Computational Materials (2022)

-

Automated stopping criterion for spectral measurements with active learning

npj Computational Materials (2021)