Abstract

Stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (sTILs) are important prognostic and predictive biomarkers in triple-negative (TNBC) and HER2-positive breast cancer. Incorporating sTILs into clinical practice necessitates reproducible assessment. Previously developed standardized scoring guidelines have been widely embraced by the clinical and research communities. We evaluated sources of variability in sTIL assessment by pathologists in three previous sTIL ring studies. We identify common challenges and evaluate impact of discrepancies on outcome estimates in early TNBC using a newly-developed prognostic tool. Discordant sTIL assessment is driven by heterogeneity in lymphocyte distribution. Additional factors include: technical slide-related issues; scoring outside the tumor boundary; tumors with minimal assessable stroma; including lymphocytes associated with other structures; and including other inflammatory cells. Small variations in sTIL assessment modestly alter risk estimation in early TNBC but have the potential to affect treatment selection if cutpoints are employed. Scoring and averaging multiple areas, as well as use of reference images, improve consistency of sTIL evaluation. Moreover, to assist in avoiding the pitfalls identified in this analysis, we developed an educational resource available at www.tilsinbreastcancer.org/pitfalls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the complexity of the immune system and intricate interplay between tumor and host antitumor immunity, detection of stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (sTILs), as quantified by visual assessment on routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides, has emerged as a robust prognostic and predictive biomarker in triple-negative and HER2-positive breast cancer1,2,3. Stromal TILs are defined as mononuclear host immune cells (predominantly lymphocytes) present within the boundary of a tumor that are located within the stroma between carcinoma cells without directly contacting or infiltrating tumor cell nests. Stromal TILs are reported as a percentage, which refers to the percentage of stromal area occupied by mononuclear inflammatory cells over the total stromal area within the tumor (i.e., not the percentage of cells in the stroma that are lymphocytes). Intratumoral TILs (iTILs), on the other hand, are defined as lymphocytes within nests of carcinoma having cell-to-cell contact with no intervening stroma. Initial studies of TILs in breast cancer evaluated stromal and intratumoral lymphocytes separately and while both correlated with outcome, sTILs were more prevalent, more variable in amount and shown to be more reproducibly assessed4,5,6,7. As such, recommendations for standardized assessment of TILs in breast cancer by the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group (also referred to as TIL-Working Group, or TIL-WG in the manuscript; www.tilsinbreastcancer.org) recommend assessing sTILs whilst strictly adhering to the definition as outlined above8.

Stromal TILs are prognostic for disease-free and overall survival in early triple-negative breast cancers treated with standard anthracycline-based adjuvant chemotherapy4,5,6,9,10. High levels of sTILs are associated with improved outcome and increased response to neoadjuvant therapy in both triple-negative and HER2-positive breast cancers7,11,12,13,14. Recently, experts at the 16th St. Gallen International Breast Cancer Conference endorsed routine reporting of sTILs in triple-negative breast cancer15. Studies involving or evaluating prognosis should now include the evaluation of sTILs.

The expanding role sTILs play in breast cancer research, prognosis and increasingly patient management, is predicated on accurate assessment of sTILs. The pivotal studies cementing the prognostic and predictive role of sTILs have been performed by visual assessment on H&E-stained slides according to published recommendations8. In the future, advances in machine learning may open the door to automated sTIL assessment16. Until that point, however, the onus for accurate sTIL assessment falls upon the pathologist.

Management of breast cancer is continually evolving. In contrast to the excisional biopsies of previous decades, an initial diagnosis of breast cancer is now routinely rendered on needle biopsy specimens. These small biopsies are particularly susceptible to influence of tumor heterogeneity, limited tumor sampling and technical artifacts such as crushing. Studies assessing concordance of TILs between core needle biopsies and matched surgical specimens (lumpectomy or mastectomy) report higher average TIL counts (4.4–8.6% higher) in the surgical specimens17,18. The difference in TIL scores between biopsies and surgical specimens was found to be reduced when the number of cores was increased18, suggesting tumor heterogeneity as a contributing factor. Not specifically addressed was the tissue reaction and inflammatory infiltrate associated with the biopsy procedure itself. No increase in TIL scores within the surgical specimens was seen when surgery was performed within 4 days of the biopsy procedure. Conversely, surgery performed more than 4 days post biopsy was an independent factor correlating with higher TILs in the surgical specimen17. This corresponds to the timing of chronic inflammatory infiltrates in wound healing. It should be noted, however, that in most contemporary practice settings the delay between biopsy and surgery is several weeks and per the recommended guidelines, areas of scarring should be excluded from sTIL assessment. The inflammation associated with wound healing is physically limited closely to the healing area and does not spread extensively into the tumor itself or surrounding stroma. Thus the impact of the biopsy procedure on sTIL levels in the surgical specimen is likely minimal.

Routine use of neoadjuvant therapy is increasingly common in triple-negative and HER2-positive breast cancers. These trends necessitate that sTIL assessment be performed on small biopsy samples and, in the absence of complete pathological response, on postneoadjuvant excision specimens without compromising accuracy. High levels of sTILs in residual tumor post neoadjuvant therapy is associated with improved outcome in TNBC19,20. As neoadjuvant samples possess distinct challenges, separate recommendations for assessing TILs in residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy have been published21.

Breast cancers show wide variation in morphology, particularly in tumor cellularity and amount of tumor stroma. Two tumors of the same size may exhibit the same absolute numbers of stromal lymphocytes but have a different percentage of sTILs due to the stromal content as a proportion of tumor area. High-grade tumors can show extensive central necrosis with only a thin rim of viable tumor resulting in minimal assessable tumor stroma even in large resection specimens. Other inflammatory cells are not infrequently seen infiltrating tumor stroma, including neutrophils, eosinophils and macrophages, resulting in a more cellular appearance and rendering assessment of stromal TIL density more challenging. Apoptotic cells can mimic lymphocytes. Poor fixation and technical artifacts in cutting and staining are recognized to compromise sTIL assessment. Ill-defined tumor borders and widely separated nests of tumor result in variability in defining what constitutes tumor stroma. Preexisting lymphocytic aggregates surrounding normal ducts and lobules, vessels or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) can also confound assessment. Heterogeneity in sTIL distribution both within the tumor and at the invasive front versus the central tumor all contribute to variation in pathologist sTIL assessment.

In an effort to identify the sources of variation in assessment of sTILs, we analyzed data and images from three-ring studies performed by TIL-WG pathologists specifically evaluating concordance in sTIL evaluation in breast cancer22,23. Based on the findings of this analysis we designed an educational resource available via the International Immuno-Oncology Working Group website at www.tilsinbreastcancer.org/pitfalls to assist pathologists in avoiding the different types of pitfalls identified. In addition, we evaluated the impact of sTIL discrepancy on outcome estimation using the data of a pooled analysis of 9 phase III clinical trials9.

Results

Identification of cases demonstrating variability using ring studies by the TIL-Working Group

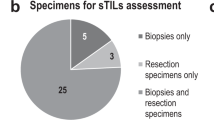

Three-ring studies evaluating concordance of sTIL assessment in breast cancer were analyzed (Fig. 1). In the first ring study, 32 pathologists evaluated 60 scanned breast cancer core biopsy slides22. This international group of pathologists from 11 different countries were all members of the TIL Working Group. Some had a special interest or subspecialty training in breast pathology, while others were general surgical pathologists, illustrating the wide applicability of the approach. The only instructions given to the scoring pathologists were to read and use the TIL assessment guidelines published by the TIL working group8. The second ring study was an extension of the first study using a more formalized approach. A subset of 28 of the original 32 pathologists participated and scored 60 different scanned breast cancer core biopsy slides. In this study, each pathologist identified and scored at least three separate 1 mm2 regions on each slide, representing the range of sTIL variability and averaged the results into a final score. Additionally, reference images representing different sTIL percentages were integrated into the evaluation process (Fig. 2)22. The last ring study was performed by six TIL-WG pathologists who independently scored 100 scanned whole section (excision specimen) breast cancer cases23.

Raw data and original scanned images from 3 previously performed ring studies were evaluated (shaded Box 1).

Available at www.tilsinbreastcancer.org.

In total, results from 220 slides were included for statistical analysis (60 each from ring studies 1 and 2, and 100 from ring study 3). The standard deviation for sTIL scores for each slide is shown in Fig. 3. When comparing across studies, ring study 2 shows the least variation in sTIL scores between pathologists. The cases with the 10% greatest standard deviation were identified (Fig. 3 red squares) and the original scanned slides of the cases were reviewed to identify factors contributing to discordant sTIL assessment in these cases. Additionally, in Ring Study 1, a single outlier case in the low sTIL range was also evaluated (Fig. 3a black triangle). From Ring Study 3, three additional cases showing large standard deviation were also included in the scanned slide assessment (Fig. 3c black triangles). Overall, a total of 26 original scanned images were reviewed by ZK (ring studies 1 and 2) and RK (ring study 3) from cases identified as particularly problematic (i.e., showing high variability) in sTIL assessment.

a Ring study 1, 32 pathologists evaluated 60 scanned core biopsy specimens. b Ring study 2, 28 pathologists evaluated 60 scanned core biopsy specimens. c Ring study 3, 6 pathologists evaluated 100 scanned whole section specimens. 10% of cases in each study showing the greatest variability in sTIL scores are shown as red squares. Black triangles identify additional cases identified for slide assessment.

Analysis of scoring variance between pathologists

Table 1 shows the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and concordance rate among pathologists for each of the 3 studies. The ICC is the proportion of total variance (in measurements across patients and laboratories) that is attributable to the biological variability among patients’ tumors, while 1 – ICC is the proportion attributable to pathologist variability. The ICC has a range from 0 to 1 with a score of 1 having the maximum agreement. Concordance rates were evaluated comparing different sTIL cutpoints: <1 vs ≥1%; <5 vs ≥5%; <10 vs ≥10%; <30 vs ≥30%; <75 vs ≥75% for each pathologist by comparing all pairs of pathologists.

The ICC was highest in ring study 2 compared to the other studies. Ring study 2 specifically sought to mitigate effects of sTIL heterogeneity with assessment of 3 separate areas and intra-pathologist scoring bias by necessitating use of standardized percentage sTIL reference images.

Evaluation of sources of variability in the three-ring studies

The scanned images of the H&E-stained slides from the most discordant cases in each of the 3 ring studies were evaluated to identify the histological factors contributing to the variation in sTIL assessment. In total 26 original scanned images were reviewed—7 from ring study 1, 6 from ring study 2 and 13 from ring study 3. Often multiple factors were present in each slide.

Heterogeneity in sTIL distribution

Heterogeneity in sTIL distribution was identified as a major contributing factor in all of the ring studies and as the most prevalent challenge in ring studies 1 and 2 (Table 2; Fig. 4). Based on review of the most variable cases, increased sTIL density at the leading edge versus central tumor were contributing factors in 43%, 17% and 54% of cases in ring studies 1 through 3, respectively (Fig. 4a); and marked heterogeneity of sTIL density within the tumor was identified in 29% cases in ring study 1 only (Fig. 4b). Whereas in ring studies 1 and 3 pathologists provided a global sTIL assessment based simply on the published scoring recommendations8, ring study 2 specifically addressed the issue of sTIL heterogeneity by requiring separate scoring of at least 3 distinct areas of the tumor representing the range of sTIL density. Additionally, matching the tumor area observed with reference percent sTIL images were a necessary part of the evaluation. Our analysis supports that scoring and averaging multiple areas aids in providing a more consistent result between pathologists. One issue not resolved by this technique is the scenario of a tumor comprised of variably spaced apart clusters of epithelial cells with a dense lymphocytic aggregate associated with each cluster of epithelial nests but sparse infiltrate between the clusters (Fig. 4c). This pattern was identified as a contributing factor in 29% of highly discordant cases in ring study 1, 50% of discordant cases in ring study 2 and no cases in ring study 3. There appears to be uncertainty amongst pathologists in this situation as to whether to only include the stroma associated with—but not touching—tumor epithelium (showing high sTIL density) or all stroma within the tumor mass including stroma intervening between spaced apart clusters of malignant epithelium (showing low sTIL density). This uncertainty increases variability in sTIL assessment and would be reduced by strict adherence to the definition of sTILs provided in the introduction. All stroma within a single tumor is to be included within the sTIL assessment. In this situation, both the higher density areas in close proximity to tumor cells and the lower density areas located between epithelial clusters should be included. One notable exception is a tumor with a central hyalinized scar, where the acellular scar tissue should be excluded from sTIL assessment.

Different examples of heterogeneity include a increased sTILs at the leading edge (blue arrow) compared to the central tumor (yellow arrow); b marked heterogeneity in sTIL density within the tumor; and c variably spaced apart clusters of cancer cells with a dense tight lymphocytic infiltrate separated by collagenous stroma with sparse infiltrate.

Technical factors

Technical factors were the next largest source of discordance (Table 3; Fig. 5). Poor quality slides with histological artifacts, as can be seen secondary to prolonged ischemic time, poor fixation, issues during processing, embedding or microtomy were identified as a contributing factor for discordance in 85% of the most discordant scanned slides from ring study 3 (Fig. 5a). In contrast, this was not deemed a contributing factor in any of the cases from ring studies 1 or 2. These results are highly skewed based on the studies assessed. Ring study 3 used a subset of H&E slides from NSABP-B31, an older completed trial evaluating benefit of trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer, which started accrual in February 2000 across multiple centers. These were excision specimens undergoing local community tissue processing. Variable ischemic and fixation times subsequently affected the integrity of stromal connective tissue which is critical in sTIL assessment. Ring studies 1 and 2 used pretherapeutic core biopsies from the neoadjuvant GeparSixto trial, which accrued between August 2011 and December 2012. Fixation and ischemic time are less likely to have been an issue in these samples, which (i) as biopsy samples are immediately placed in formalin without requirement for serial sectioning and can be processed in a timely fashion and (ii) were procured at a time when the preanalytic variables had become substantially better understood and new recommendations widely adopted. Not to mention, H&E stains fade with passage of time, which itself impacts the ability to produce quality scanned images. In the current era, with awareness and adoption of standardization and monitoring of preanalytical and analytical variables, poor quality H&E slides should no longer be acceptable. Nonetheless, challenges remain and variations in practice can result in poorly processed specimens that are likely to directly and negatively impact sTIL assessment. Crush artifact, which is more commonly seen in core biopsy samples, was seen in 1 case overall in ring study 1 (14%) (Fig. 5b).

Out-of-focus scans were identified in 1 case each in ring study 1 (14%) and ring study 2 (17%) (Fig. 5c). In clinical practice, particularly as sTILs are poised to impact patient management, an out-of-focus slide should be rescanned before scoring. Notably, this highlights an obstacle to incorporation of whole slide imaging in routine practice. Consistent focus quality remains an issue requiring dedicated support staff for loading, scanning, reviewing and rescanning if necessary24.

Including wrong area or cells

Variability in defining the tumor boundary and scoring stroma outside of the tumor boundary appears to have been a contributing factor for variation in 33% of highly discordant cases in ring study 2 and 15% of cases in ring study 3 (Table 4; Fig. 6a). The discordant cases also highlighted situations of including lymphocytes associated with DCIS (2 cases ring study (RS)1, 1 case RS2) (Fig. 6a), lymphocytes associated with a component of the tumor showing features of an encapsulated papillary carcinoma (1 case RS1) (Fig. 6b), and lymphocytes associated with benign terminal duct lobular units (1 case RS1) (Fig. 6d). Difficulty distinguishing iTILs from sTILs factored into 2 cases (29%) in ring study 1 and 1 case (17%) in ring study 2 (Fig. 7a). Also identified in ring study 1 was 1 case (14%) with prominent stromal neutrophils (Fig. 7b) and 1 case (14%) with stromal histiocytes (Fig. 7c). It is important to assess slides at a sufficiently high power to be able to differentiate between types of immune cells. Neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, and histiocytes/macrophages are all excluded from sTIL assessment. Two independent cases in ring study 1 demonstrated misinterpretation of apoptotic cells for lymphocytes (Fig. 7d) and artefactual falling apart of tumor cell nests along the edge of a core biopsy mimicking the discohesive appearance of TILs (Fig. 7e). Both are previously noted examples of histomorphologic challenges.

Scenarios where there may be challenges in deciding which areas to score include a difficulty defining the tumor boundary (dashed line) and including fibrous scars (yellow arrow) or lymphoid aggregates (blue arrow) beyond the invasive front; b including lymphocytes surrounding ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) which may be difficult to distinguish from invasive carcinoma; c including lymphocytes associated with an encapsulated papillary carcinoma component of a tumor; and d including lymphocytes surrounding benign glands. Shown is invasive carcinoma (yellow arrows) surrounding a benign lobule with associated lymphocytes; adjacent benign lobules (blue arrows) show dense lymphoid aggregates identify the lymphocytic infiltrate to be related to the entrapped lobule rather than the carcinoma.

Limited stroma within tumor for evaluation

An added factor identified was the presence of minimal stroma in the tumor for assessment (Table 5; Fig. 8a). This was identified as a contributing factor in 46% of cases in ring study 3. In a variation, 1 case (14%) in ring study 1 showed extensive tumor necrosis with decreased available stroma for assessment (Fig. 8b). Two cases (15%) of mucinous tumors, each with minimal stroma to assess were identified in ring study 3 (Fig. 8c).

Clinical significance of variability in sTIL assessment by pathologists

The online triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)-prognosis tool (www.tilsinbreastcancer.org) that contains cumulative data of 9 phase III TNBC-trials9, was used to analyze the impact of variation in sTIL assessments (using the sTIL-scores of this analysis) on outcome. The impact on outcome of different sTIL levels is represented in Fig. 9, showing a prototypical example of a 60-year-old patient with a histological grade 3 triple-negative breast carcinoma, measuring between 2 and 5 cm (pT2) and showing 30% sTILs. Assuming she is node negative, if a pathologist properly quantifies the percentage of sTILs, the 5-years invasive disease-free survival (iDFS) is estimated at 76%. If the pathologist deviates down 10% in scoring sTILs (i.e., 20% sTILs), the 5-years iDFS decreases to 73%. Conversely, if the pathologist deviates up 10% in scoring sTILs (i.e., 40% sTILs), the 5-years iDFS goes up to 79%. These differences are modest from a purely prognostic viewpoint, although larger variations would lead to more pronounced differences in outcome estimation. If cutpoints are used to decide on therapy, on the other hand, variation in values around the cut point (as reflected in the concordance rates in Table 1 and Supplemental material) may impact clinical management. Additional examples of outcome estimation as a function of sTILs are provided in the Supplemental material.

Shown is the variation in estimated outcome based on sTIL assessment for a 60-year-old patient with a histological grade 3 tumor, 2–5cm in size and receiving anthracycline+taxane based chemotherapy. Presuming a true value for sTILs of 30%, changes in estimated 5-year iDFS for 5, 10, and 20% deviations (increase and decrease) in sTIL assessments are represented with 95% confidence bands. (All calculations were performed using the online triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)-prognosis tool9 available at www.tilsinbreastcancer.org).

A new resource for pathologists

To assist pathologists in avoiding the different types of pitfalls in the assessment of sTILs identified in this analysis, we have developed an educational tool available via the International Immuno-Oncology Working Group website at www.tilsinbreastcancer.org/pitfalls. Both conventional pictures of microscopic slides and digitized whole slide images (WSIs) of biopsies and surgical resection specimens of breast and other cancers are available to illustrate the described pitfalls. At this point in time, we have included several examples of each of the pitfalls. In the future, we intend to add extra illustrative examples to make this collection a ‘living’ library and continuously evolving learning tool for the pathology community. We invite the pathology community to provide examples of challenging cases for TIL evaluation via the website.

Discussion

In the current study, we evaluated factors which serve to increase the interobserver variability of manual sTILs assessment. The data were analyzed as both continuous and categorical variables. Despite the challenges pathologists face in scoring sTILs, the reported prognostic and predictive value of sTILs remains consistent across multiple datasets analyzed by independent investigators9,25. On the individual patient level, however, we have shown that discrepancies in sTILs scoring between pathologists results in different individual outcome estimations, requiring refinements in the paradigm to maximize benefit and minimize risk.

Notable strengths of this study include the evaluation of both core biopsy and excision specimens, which reflect the reality of clinical practice in which sTIL assessment will be performed. Analyzing the concordance rates across various cutpoints allows us to inform regarding reproducibility to aid in educated cut point selection for future trials. If a singular cutpoint is used, variation in values around that cutpoint can result in misassignment. However, in the setting of an understanding of the scoring error, the cutpoint can be adjusted to a range such that below is X, above is Y and between is indeterminate, and based on a strategy of risk management the overall risk is mitigated. The extensive reference images in this manuscript, as well as the online education resource with further examples (www.tilsinbreastcancer.org/pitfalls), are a valuable reference guide to the pathology community.

A limitation to consider is the poor quality of many of the slides from the excision specimen sections in ring study 3 that were identified as showing the highest discordance. This skewed the evaluation towards technical factors, which are likely to be less of an issue in contemporary clinical practice, but are of relevance in retrospective analyses from older clinical trials. Nonetheless, if presented with such a case in practice, only intact, morphologically assessable areas should be included in sTIL score. If applicable, one could attempt recutting and staining a new slide or selecting a different block for assessment. This information further bolsters the demands for optimal tissue handling and processing.

Among the sources of variability identified, the greatest challenge appears to be dealing with heterogeneous distribution of sTILs. This issue was partially mitigated in ring study 2 which required assessment and averaging of at least 3 separate areas of tumor. The areas were selected by the pathologist to reflect the range of sTIL density and could be within a single core or across separate cores depending on the case. One may postulate that the increased experience of having participated in ring study 1 accounts for the greater concordance in ring study 2; however, the pathologists in ring study 3 had participated in the previous two ring studies and nonetheless showed lower ICC and concordance rates than ring study 2. Ring study 3 was the only study using whole sections compared to core biopsies in the other two studies. One could consider that the increased area of tumor in an excision specimen could lead to increased discordance26. In reality, however, many of the core biopsy cases contained multiple tissue cores per slide with multiple separate fragments of tumor, which likely negated any benefit of smaller tumor area. Although the recommendation to score multiple areas and average them in the setting of a heterogeneous tumor is within the published recommendation guidelines8, the software in ring study 2 made this a firm requirement. Similarly, use of reference % sTIL images is recommended in the guideline but was a mandatory component of ring study 2. We identified these two key recommendations from the scoring guidelines as having a major impact on consistency of results. These two relatively simple steps: scoring multiple areas in heterogeneous tumors and always using reference images (to minimize personal assessment bias to always “score high” or “score low”)27 substantially improve concordance. This re-enforces the central importance of adhering to recommendations in the scoring guidelines. Once factors of heterogeneity are excluded, taking the time to evaluate slides at a sufficiently high power to distinguish lymphocytes from other immune cells as well as mimics can further improve concordance. Being cognizant of lymphoid aggregates around benign ducts and lobules, vessels and DCIS outside of the tumor will help identify these as unrelated to the invasive carcinoma when present within the tumor boundary where these lymphoid aggregates should be excluded from sTIL assessment.

Demonstration of the reproducibility of sTILs scoring is essential for widespread adoption. The importance of sTILs as a biomarker is being increasingly recognized resulting in recommendations by multiple respected groups. The 2019 St. Gallen Panel recommended that sTILs be routinely characterized in TNBC for their prognostic value8,15. As of yet, however, insufficient data exists to recommend sTILs as a test to guide systemic treatment. In addition, the latest iteration of the WHO Classification of Breast Tumours also includes information on sTILs28.

Stromal TIL-assessment by pathologists is now recognized as an analytically and clinically validated biomarker. There is Level 1B evidence that high levels of sTILs are associated with improved outcome and an enhanced response to neoadjuvant therapy in triple-negative and HER2-positive breast cancers7,11,12,13,14,29, and are prognostic for disease-free and overall survival in early triple-negative breast cancers treated with standard anthracycline-based adjuvant chemotherapy4,6,9. Clinical utility [likelihood of improved outcomes from use of the biomarker test compared to not using the test]30 remains to be defined. A recent retrospective study demonstrated that patients with Stage I TNBC with >30% sTILs had excellent survival outcomes (5-year overall survival rate of 98% [95%CI: 95% to 100%]) in the absence of chemotherapy31, paving the way for future randomized trials of chemotherapy de-escalation in early TNBC.

Clinical utility for sTILs is also likely to come from cancer immunotherapy, a rapidly emerging field aimed at augmenting the power of a patient’s own immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. The immune system is able to impart selective pressure on cancer cells resulting in immune-evading clones. Stromal TILs can identify tumors amenable to immunotherapies targeting immunosuppression32. Checkpoint inhibitors of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) are promising therapeutic interventions, however predicting tumor response to these agents remains challenging33. There is increasing hesitation about the utility of the current predictive biomarker PD-L1 expression by IHC. The utility of PD-L1 IHC is undermined by the well-characterized geographic and temporal heterogeneity and dynamic expression on tumor or tumor-infiltrating immune cells34. Technical differences, variable expression and variation in screening thresholds for PD-L1 expression across assays pose additional limitations. Studies have shown that although pathologists can score PD-L1 on tumor cells with high concordance, even with training they are not concordant in scoring PD-L1 on immune cells35,36,37. There are emerging data that sTILs, as assessed by the consensus-method defined by the TIL Working Group, are predictive for response to checkpoint-inhibition in metastatic triple-negative and HER2-positive breast cancer38,39. The response rate is linear with increasing sTILs related to a higher response rate39. Further investigations are ongoing.

As we look to the future, automated sTIL assessment holds the promise of adding complementarity to the current pathological evaluation of breast cancers. A heterogeneous pattern of lymphocyte infiltration may be better addressed with computational pathology methods40,41. Further, there is some evidence that the spatial distribution of TILs may provide additional prognostic information42. One study reported improved prognosis and response to chemotherapy in TNBC with a diffuse, homogeneous lymphocyte distribution versus a heterogeneous distribution43. This requires further evaluation. Lymphocytes are particularly well-suited to image analysis, as it is easier to recognize these small blue dark cells against a stromal background than, for example, to distinguishing malignant cells from normal epithelium. There is a surge in the development of machine learning methods for TIL assessment44. The histopathologic diagnostic responsibility will continue to reside with the pathologist. Image analysis and computation pathology, which are proven to be faster and more reproducible, are adjuncts that aid the pathologist but do not replace the function of histopathologic interpretation. Until these tools are available, the well-educated and well-trained pathologist is the best approach. Rigorous training, evaluation and practice are well documented to result in improved intra- and inter-pathologist reproducibility. It is hoped that by highlighting the specific pitfalls in sTIL assessment in this manuscript – the forewarned pathologist is the forearmed pathologist. Ongoing efforts to ensure reliable and reproducible reporting of sTILs are a key step in their smooth progression into the routine clinical management of breast cancer.

Methods

Identification of cases demonstrating variability using ring studies by the TIL-Working Group

We identified 3 ring studies evaluating concordance of sTIL assessment in breast cancer performed by TIL-WG pathologists, for which we could obtain individual pathologist data and images22,23. The ring studies were performed on clinical trials material. All participating patients gave written informed consent to sample collection and the use of these samples for translational biomarker research, as approved by the Ethics Commission of the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin. All relevant ethical regulations have been complied with for this study. In ring study 1, 32 pathologists evaluated 60 scanned breast cancer core biopsy slides22. Scores were missing for 5 slides; the missing values were replaced by the mean of the 31 remaining scores. Ring study 2 was an extension of the first study. A subset of 28 of the original 32 pathologists participated and scored 60 different scanned breast cancer core biopsy slides22. Ring study 3 was performed by six TIL-WG pathologists who independently scored 100 scanned whole slide breast cancer cases23. In total, 220 slides were included. For each individual slide, the variability (standard deviation) among pathologists was measured from individual sTILs scores. The slides with the highest 10% standard deviation were identified for evaluation.

Statistical analysis of scoring variance between pathologists

The R software environment was used for statistical computing and graphics (version 3.5.0). Scoring variance among pathologists was analyzed using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). ICC estimates and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated based on individual-pathologist rating (rather than average of pathologists), absolute-agreement (i.e., if different pathologists assign the same score to the same patient), 2-way random-effects model (i.e., both pathologists and patients are treated as random samples from their respective populations)45. To compute ICC, we used the “aov” function to fit the data with a two-way random effect ANOVA model (readers and cases). We followed Fleiss and Shrout’s method to approximate the ICC confidence intervals46. We created custom code for the concordance analysis. Concordance rates for all pairs of pathologists were calculated at several sTIL density cutpoints: <1 vs ≥1%; <5 vs ≥5%; <10 vs ≥10%; <30 vs ≥30%; <75 vs ≥75%. Specifically, each concordance was the percent agreement from the 2 × 2 table created from each cutpoint and pair of readers. The analyses were performed and confirmed independently by two separate groups (RE & SM; Gustave Roussy) and (BDG & WC; FDA). Details of the concordance analysis are presented in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Evaluation of sources of variability in the three-ring studies

Slides for ring study 1 and 2 were Whole Slide Images (WSI) and were viewed using a virtual microscope program (CognitionMaster Professional Suite; VMscope GmbH). Each slide identified as showing the top 10% discordance, as well as specifically chosen cases (1 outlier low sTIL case in ring study 1 and 3 additional high discordance cases from ring study 3) were examined in order to identify potential confounding factors for routine sTIL assessment.

Clinical significance of variability in sTIL assessment by pathologists

The impact of variation in sTILs on outcome estimation was evaluated using the online triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)-prognosis tool (www.tilsinbreastcancer.org) that contains cumulative data of 9 phase III TNBC-trials. The sTIL scores of this analysis were used as the ground truth. Specifically, different patient profiles were defined based on standard clinicopathological factors: age, tumor size, number of positive nodes, tumor histological grade and treatment. For a specific patient profile and a value of sTIL, the tool was used to calculate the 5-year invasive disease-free survival (iDFS). The iDFS is defined as the date of first invasive recurrence, or second primary or death from any cause.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The histology images supporting Fig. 2 and Figs. 4–8, are publicly available in the figshare repository, as part of this record: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1190776847. Data supporting Fig. 3, Tables 1–5 and Supplementary Tables 1–3 are not publicly available in order to protect patient privacy. These datasets can be accessed on request from Dr. Roberto Salgado, upon the completion of a Data Usage Agreement, according to policies from the German Breast Group and NSABP, as described in the data record above. Figure 9 and supplementary figures 1–8, were generated using the publicly available prognosis tool at www.tilsinbreastcancer.org/, which utilises datasets from a pooled analysis of 9 phase 3 breast cancer trials, including BIG 02-98, ECOG 1199, ECOG 2197, FinHER, GR, IBCSG 22-00, IEO, PACS01 and PACS04 (https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01010). This paper is intended to serve as a practical reference for practicing pathologists.

Code availability

The code is available from the corresponding author by request.

References

Savas, P. et al. Clinical relevance of host immunity in breast cancer: from TILs to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 13, 228–241 (2016).

Hammerl, D. et al. Breast cancer genomics and immuno-oncological markers to guide immune therapies. Semin Cancer Biol. 52, 178–188 (2018).

Hudecek, J. et al. Application of a risk-management framework for integration of stromal Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes in clinical trials. npj Breast Cancer https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-020-0155-1 (2020).

Adams, S. et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancers from two phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trials: ECOG 2197 and ECOG 1199. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 2959–2966 (2014).

Loi, S. et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are prognostic in triple negative breast cancer and predictive for trastuzumab benefit in early breast cancer: results from the FinHER trial. Ann. Oncol. 25, 1544–1550 (2014).

Loi, S. et al. Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trial in node-positive breast cancer comparing the addition of docetaxel to doxorubicin with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: BIG 02-98. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 860–867 (2013).

Denkert, C. et al. Tumor-associated lymphocytes as an independent predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 105–113 (2010).

Salgado, R. et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann. Oncol. 26, 259–271 (2015).

Loi, S. et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis: a pooled individual patient analysis of early-stage triple-negative breast cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 559–569 (2019).

Dieci, M. V. et al. Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in two phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trials. Ann. Oncol. 26, 1698–1704 (2015).

Denkert, C. et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol. 19, 40–50 (2018).

Denkert, C. et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without carboplatin in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive and triple-negative primary breast cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 983–991 (2015).

Issa-Nummer, Y. et al. Prospective validation of immunological infiltrate for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-negative breast cancer-a substudy of the neoadjuvant GeparQuinto trial. PLoS One 8, e79775 (2013).

West, N. R. et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes predict response to anthracycline-based chemotherapy in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 13, R126 (2011).

Burstein, H. J. et al. Estimating the benefits of therapy for early stage breast cancer The St Gallen International Consensus Guidelines for the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2019. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1541–1557 (2019).

Amgad, M. et al. Report on computational assessment of Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes from the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker WorkingGroup. npj Breast Cancer https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-020-0154-2 (2020).

Huang, J. et al. Changes of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes after core needle biopsy and the prognostic implications in early stage breast cancer: a retrospective study. Cancer Res Treat. 51, 1336–1346 (2019).

Cha, Y. J. et al. Comparison of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes of breast cancer in core needle biopsies and resected specimens: a retrospective analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 171, 295–302 (2018).

Luen, S. J. et al. Prognostic implications of residual disease tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and residual cancer burden in triple-negative breast cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 30, 236–242 (2019).

Luen, S. L., Salgado, R. & Loi, S. Residual disease and immune infiltration as a new surrogate endpoint for TNBC post neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Oncotarget 10, 4612–4614 (2019).

Dieci, M. V. et al. Update on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer, including recommendations to assess TILs in residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy and in carcinoma in situ: A report of the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group on Breast Cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 52, 16–25 (2018).

Denkert, C. et al. Standardized evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer: results of the ring studies of the international immuno-oncology biomarker working group. Mod. Pathol. 29, 1155–1164 (2016).

Kim, R. S. et al. Stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in NRG oncology/NSABP B-31 adjuvant trial for early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst 111, 867–871 (2019).

Boyce, B. F. An update on the validation of whole slide imaging systems following FDA approval of a system for a routine pathology diagnostic service in the United States. Biotech. Histochem. 92, 381–389 (2017).

Loi, S. Host antitumor immunity plays a role in the survival of patients with newly diagnosed triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 2935–2937 (2014).

Gavrielides, M. A., Conway, C., O’Flaherty, N., Gallas, B. D. & Hewitt, S. M. Observer performance in the use of digital and optical microscopy for the interpretation of tissue-based biomarkers. Anal. Cell Pathol. (Amst.) 2014, 157308 (2014).

Gavrielides, M. A., Gallas, B. D., Lenz, P., Badano, A. & Hewitt, S. M. Observer variability in the interpretation of HER2/neu immunohistochemical expression with unaided and computer-aided digital microscopy. Arch. Pathol. Lab Med. 135, 233–242 (2011).

WHO classification of tumours editorial board. Breast Tumours. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed., vol. 2) (International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France, 2019).

Simon, R. M., Paik, S. & Hayes, D. F. Use of archived specimens in evaluation of prognostic and predictive biomarkers. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 101, 1446–1452 (2009).

Hayes, D. F. et al. Tumor marker utility grading system: a framework to evaluate clinical utility of tumor markers. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 88, 1456–1466 (1996).

Park, J. H. et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1941–1949 (2019).

Esteva, F. J., Hubbard-Lucey, V. M., Tang, J. & Pusztai, L. Immunotherapy and targeted therapy combinations in metastatic breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 20, e175–e186 (2019).

Gong, J., Chehrazi-Raffle, A., Reddi, S. & Salgia, R. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive review of registration trials and future considerations. J. Immunother. Cancer 6, 8 (2018).

Balar, A. V. & Weber, J. S. PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies in cancer: current status and future directions. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 66, 551–564 (2017).

Hirsch, F. R. et al. PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry Assays for Lung Cancer: Results from Phase 1 of the Blueprint PD-L1 IHC Assay Comparison Project. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12, 208–222 (2017).

Tsao, M. S. et al. PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry Comparability Study in Real-Life Clinical Samples: Results of Blueprint Phase 2 Project. J. Thorac. Oncol. 13, 1302–1311 (2018).

Rimm, D. L. et al. A prospective, multi-institutional assessment of four assays for PD-L1 expression in NSCLC by immunohistochemistry. JAMA Oncol. 3, 1051–1058 (2017).

Loi, S. et al. Phase Ib/II study evaluating safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab and trastuzumab in patients with trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: Results from the PANACEA (IBCSG 45-13/BIG 4-13/KEYNOTE-014) study. Cancer Res. 78(4 Suppl):Abstract nr GS2-06. (2018)

Loi, S. et al. LBA13Relationship between tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) levels and response to pembrolizumab (pembro) in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC): Results from KEYNOTE-086. Ann Oncol. 28 (suppl_5), v605–v649 (2017).

Corredor, G. et al. Spatial architecture and arrangement of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for predicting likelihood of recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 1526–1534 (2019).

Bera, K., Velcheti, V. & Madabhushi, A. Novel quantitative imaging for predicting response to therapy: techniques and clinical applications. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 38, 1008–1018 (2018).

Saltz, J. et al. Spatial organization and molecular correlation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes using deep learning on pathology images. Cell Rep. 23, 181–193 (2018). e7.

Hida, A. I. et al. Diffuse distribution of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes is a marker for better prognosis and chemotherapeutic effect in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 178, 283–294 (2019).

Klauschen, F. et al. Scoring of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes: From visual estimation to machine learning. Semin Cancer Biol. 52, 151–157 (2018).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163 (2016).

Fleiss, J. L. & Shrout, P. E. Approximate interval estimation for a certain intraclass correlation coefficient. Psychometrika 43, 259 (1978).

Kos, Z. et al. Metadata supporting data files in the published article: pitfalls in assessing stromal tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (sTILs) in breast cancer. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11907768 (2020).

Acknowledgements

R.S. is supported by a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF, grant No. 17-194). S.L. is supported by the National Breast Cancer Foundation of Australia Endowed Chair (NBCF-17-001) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, New York (BCRF-19-102). S.G. is supported by Susan G Komen Foundation (CCR18547966) and a Young investigator Grant from Breast Cancer Alliance. T.O.N. receives funding support from the Canadian Cancer Society. A.M. acknowledges research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers 1U24CA199374-01, R01CA202752-01A1, R01CA208236-01A1, R01 CA216579-01A1, R01 CA220581-01A1, 1U01 CA239055-01, National Center for Research Resources under award number 1 C06 RR12463-01, VA Merit Review Award IBX004121A from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service, the DOD Prostate Cancer Idea Development Award (W81XWH-15-1-0558), the DOD Lung Cancer Investigator-Initiated Translational Research Award (W81XWH-18-1-0440), the DOD Peer Reviewed Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-16-1-0329), the Ohio Third Frontier Technology Validation Fund and the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation Program in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and the Clinical and Translational Science Award Program (CTSA) at Case Western Reserve University. J.S. received funding from NCI grants UG3CA225021 and U24CA215109. C.S. is a Royal Society Napier Research Professor; this work was supported by the Francis Crick Institute that receives its core funding from Cancer Research UK (FC001169, FC001202), the UK Medical Research Council (FC001169, FC001202), and the Wellcome Trust (FC001169, FC001202); C.S. is also funded by Cancer Research UK (TRACERx and CRUK Cancer Immunotherapy Catalyst Network), the CRUK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence, Stand Up 2 Cancer (SU2C), the Rosetrees Trust, Butterfield and Stoneygate Trusts, NovoNordisk Foundation (ID16584), the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF); the research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) Consolidator Grant (FP7-THESEUS-617844), European Commission ITN (FP7-PloidyNet 607722), ERC Advanced Grant (PROTEUS) has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 835297), Chromavision—this project has received funding from the European’s Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 665233); support was also provided to C.S. by the National Institute for Health Research, the University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre, and the Cancer Research UK University College London Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre. R.K. and K.P.-G. acknowledge research leading to or reported in this publication was supported by NCI U10CA180868, -180822, UG1-189867, and U24-196067 the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and Genentech.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors made a substantial contribution to the conception or design of the work and/or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of the data. All authors participated in either drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final completed version of this paper and assume accountability for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.E. is on the Roche advisory board and has reported honoraria from Amgen, Novartis and Roche. A.J.L. is a consultant for BMS, Merck, AZ/Medimmune, and Genentech. R.S. reports research funding from Roche, Puma, Merck; advisory board and consultancy for BMS; travel funding from Roche, Merck, and Astra Zeneca. S.G. reports Lab research funding from Lilly, Clinical research funding from Eli Lilly and Novartis and is a Paid advisor to Eli Lilly, Novartis, and G1 Therapeutics. J.v.d.L. is member of the scientific advisory boards of Philips, the Netherlands and ContextVision, Sweden and receives research funding from Philips, the Netherlands and Sectra, Sweden. S.A. reports Research funding to institution from Merck, Genentech, BMS, Novartis, Celgene and Amgen and is an uncompensated consultant /steering committee member for Merck, Genentech and BMS. T.O.N. has consulted for Nanostring and received compensation and has intellectual property rights/ownership interests from Bioclassifier LLC [not related to the subject material under consideration]. S.L. receives research funding to institution from Novartis, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Merck, Roche-Genentech, Puma Biotechnology, Pfizer and Eli Lilly, has acted as consultant (not compensated) to Seattle Genetics, Pfizer, Novartis, BMS, Merck, AstraZeneca and Roche-Genentech and acted as consultant (paid to her institution) to Aduro Biotech. S.R.L. has received travel and educational funding from Roche/Ventana. A.M. is an equity holder in Elucid Bioimaging and in Inspirata Inc., a scientific advisory consultant for Inspirata Inc, has served as a scientific advisory board member for Inspirata Inc, Astrazeneca, Bristol Meyers-Squibb and Merck, has sponsored research agreements with Philips and Inspirata Inc, is involved in a NIH U24 grant with PathCore Inc, and 3 different R01 grants with Inspirata Inc. and his technology has been licensed to Elucid Bioimaging and Inspirata Inc. G.C. is on the advisory boards of Roche, BMS, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics and Ellipsis, and reports personal fees from Roche, BMS, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, and Ellipsis, outside of the submitted work. J.H. is the director and owner of Vivactiv Ltd. J.H. is the director and owner of Slide Score B.V. F.P.L. reports funding from Astrazeneca, BMS, Roche, MSD, Pfizer, Novartis, Sanofi, Eli Lilly. J.B. reports consultancies from Insight Genetics, BioNTech AG, Biotheranostics, Pfizer, RNA Diagnostics and OncoXchange, research funding from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Genoptix, Agendia, NanoString Technologies, Stratifyer GmbH and Biotheranostics, applied for patents, including Jan 2017: Methods and Devices for Predicting Anthracycline Treatment Efficacy, US utility—15/325,472; EPO—15822898.1; Canada—not yet assigned; Jan 2017: Systems, Devices and Methods for Constructing and Using a Biomarker, US utility—15/328,108; EPO—15824751.0; Canada—not yet assigned; Oct 2016: Histone gene module predicts anthracycline benefit, PCT/CA2016/000247; Dec 2016: 95‐Gene Signature of Residual Risk Following Endocrine Treatment, PCT/CA2016/000304; Dec 2016: Immune Gene Signature Predicts Anthracycline Benefit, PCT/CA2016/000305. M.A.S. reports consulting work for Achilles Therapeutics. C.S. reports receipt of grants/research support from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, BMS and Ventana; receipt of honoraria, consultancy, or SAB Member fees from Pfizer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, BMS, Celgene, AstraZeneca, Illumina, Sarah Canon Research Institute, Genentech, Roche-Ventana, GRAIL, Medicxi; Advisor for Dynamo Therapeutics; Stock shareholder in Apogen Biotechnologies, Epic Bioscience, GRAIL; Co-Founder & stock options in Achilles Therapeutics. A.H.B. is the co-founder and CEO of PathAI. J.K. is an employee of PathAI. D.D. is on the advisory board for Oncology Analytics, Inc, and a consultant for Novartis. D.L.R. is on the advisory board of Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Cell Signaling Technology, Cepheid, Daiichi Sankyo, GSK, Konica/Minolta, Merck, NanoString, Perkin Elmer, Ventana, Ultivue; receives research support from Astra Zeneca, Cepheid, Navigate BioPharma, NextCure, Lilly, Ultivue; instrument support from Ventana, Akoya/Perkin Elmer, NanoString; paid consultant for Biocept; received travel honoraria from BMS, founder and equity holder for PixelGear and received royalty from Rarecyte. A.T. reports benefits from ICR’s Inventors Scheme associated with patents for one of PARP inhibitors in BRCA1/2 associated cancers, as well as honoraria from Pfizer, Vertex, Prime Oncology, Artios, honoraria and stock in InBioMotion, honoraria and financial support for research from AstraZeneca, Medivation, Myriad Genetics and Merck Serono. This work includes contributions from, and was reviewed by, individuals at the FDA. This work has been approved for publication by the agency, but it does not necessarily reflect official agency policy. Certain commercial materials and equipment are identified in order to adequately specify experimental procedures. In no case does such identification imply recommendation or endorsement by the FDA, nor does it imply that the items identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose. This work includes contributions from, and was reviewed by, individuals who received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kos, Z., Roblin, E., Kim, R.S. et al. Pitfalls in assessing stromal tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (sTILs) in breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 6, 17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-020-0156-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-020-0156-0

This article is cited by

-

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in HER2-positive breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and dual HER2-blockade

npj Breast Cancer (2024)

-

Evaluation of the prognostic potential of histopathological subtyping in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma

Virchows Archiv (2024)

-

Clinicopathological and molecular predictors of [18F]FDG-PET disease detection in HER2-positive early breast cancer: RESPONSE, a substudy of the randomized PHERGain trial

European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (2024)

-

PROACTING: predicting pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer from routine diagnostic histopathology biopsies with deep learning

Breast Cancer Research (2023)

-

Image analysis-based tumor infiltrating lymphocytes measurement predicts breast cancer pathologic complete response in SWOG S0800 neoadjuvant chemotherapy trial

npj Breast Cancer (2023)