Abstract

Ultrathin two-dimensional (2D) metal oxyhalides exhibit outstanding photocatalytic properties with unique electronic and interfacial structures. Compared with monometallic oxyhalides, bimetallic oxyhalides are less explored. In this work, we have developed a novel top-down wet-chemistry desalination approach to remove the alkali-halide salt layer within the complicated precursor bulk structural matrix Pb0.6Bi1.4Cs0.6O2Cl2, and successfully fabricate a new 2D ultrathin bimetallic oxyhalide Pb0.6Bi1.4O2Cl1.4. The unlocked larger surface area, rich bimetallic active sites, and faster carrier dynamics within Pb0.6Bi1.4O2Cl1.4 layers significantly enhance the photocatalytic efficiency for atmospheric CO2 reduction. It outperforms the corresponding parental matrix phase and other state-of-the-art bismuth-based monometallic oxyhalides photocatalysts. This work reports a top-down desalination strategy to engineering ultrathin bimetallic 2D material for photocatalytic atmospheric CO2 reduction, which sheds light on further constructing other ultrathin 2D catalysts for environmental and energy applications from similar complicate structure matrixes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultrathin two-dimensional nanomaterials (UTNs) with a typical thickness down to a few nanometres have preserved significant advantages for energy catalysis, environmental remediation, and optoelectronic applications1,2. Benefited from their large surface area, well-defined interfacial structure, intrinsic quantum-confined electrons, and tunable band structures, UTNs have been recognized as a class of very promising photocatalysts for CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR)3,4. With this regard, tremendous research works have been devoted to constructing UTNs with well-defined chemical composition and crystal/electronic structures1,5. Among all the reported UTNs, metal oxyhalide UTNs are of particular interest for CO2RR, benefiting from the heterogeneity of chemical bonding within their crystal structure, as both the covalent metal-oxygen bonding and soft ionic metal-halide bonding are co-existing within the 2D layer. Anisotropic charge distribution between the metal-oxygen layer and metal-halogen slices are retained, resulting in a prefer-oriented internal electric field within the 2D metal-oxyhalide layer6,7. Moreover, when the defect engineering approach has been employed to destruct part of the halide or oxygen atoms, a syngenetic effect of the surface exposed unsaturated metal atoms and appropriate internal electric fields are expected to be coupling together, which may contribute to the excellent charge separation property and outstanding catalytic performance in metallic oxyhalide UTNs8,9. Among all the reported metal oxyhalides, 2D bismuth oxyhalides are especially interesting10,11. With the alternative arrangement of [BimOn](3m−2n)+ layers and halogen layers, a highly dispersive and spatially anisotropic electronic structure is constructed via the anisotropic p and s-p hybridization between bismuth and halogen atoms12. These structure features provide excellent opportunities to tailor the electronic structure through vacancies modulation or heteroatoms doping for advanced photocatalysis10,13,14,15,16,17,18. Reported examples can be found in Co2+ doped Bi3O4Br atomic layers19, V5+ doped BiOIO3 20, defect-engineered BiOBr atomic layers21,22. Furthermore, different synthetic approaches have been devoted to UTNs synthesis, including chemical vapour deposition23,24, wet-chemical exfoliation25,26, micromechanical cleavage27,28, intercalation29, acid-assisted etching30,31, etc. Interestingly, most of these efforts have been solely devoted to the synthesis of high-quality monometallic oxyhalide UTNs. The bimetallic oxyhalide UTNs with well-defined elemental ratios and dual-metallic active centres are rarely reported32.

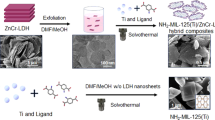

In this work, noticing the significant lower hydration energy of the ionic bonding between alkaline metal cations and halide anions within the typical framework structure matrix, herein, we have developed a novel top-down desalination strategy to unlock the bimetallic active sites from a complex parental structure matrix, in which the alkaline-halide salt layers and metal oxyhalide layers are arranged alternately. Specifically, we have synthesized an ultrathin bimetallic oxyhalide layered material Pb0.6Bi1.4O2Cl1.4 (denoted as PBOC) from its parental structure Pb0.6Bi1.4Cs0.6O2Cl2 (denoted as PBCOC). We have achieved high CO2RR efficiency on directly converting the atmospheric CO2 into solar fuels by employing the ultrathin PBOC as the photocatalyst, superior to its bulk parental material PBCOC. The novel top-down desalination strategy developed in this report provides fresh insights into the design of ultrathin 2D materials with well-defined chemical compositions from their corresponding sophisticated host structural matrixes. It paves the way for constructing prosperous ultrathin 2D catalysts for environmental and energy applications.

Results

Top-down synthesis of PBOC

The desalination strategy developed here is defined as a feasible synthetic strategy to preferably remove the ionically bonded salt-like interlayer within the complicated bulk material, where the anisotropic ionically bonded layer and covalently bonded layer are stacking alternatively. The parental structure of the bulk PBCOC material employed in this study is crystallized in the space group I4/mmm (ICSD No.88764)33, the partially occupied Cs−Cl layer is alternatively packed within the Pb0.6Bi1.4O2Cl1.4 layers as shown in Fig. 1a. The single layer of Pb0.6Bi1.4O2Cl2 shows an iso-structure of the tetragonal phase monolayered BiOCl (ICSD No. 74502), in which 30% of the Bi3+ positions are randomly occupied by Pb2+, while the packing style is significantly different from BiOCl. The interlayered Cs+ are bonded with Cl− via ionic bonds, which plays a vital role in neutralizing the extra negative charges within the layer introduced by Pb2+ substituting Bi3+ (Fig. 1a). Refer to the solubility data in aqueous solution for the corresponding pure binary compounds of all the elements involved in the framework, including CsCl, BiCl3, PbCl2, Bi2O3, PbO34, Cs−Cl is expected to have a significant water dissolution preference than Bi−Cl, Pb−Cl, Bi−O, and Pb−O bonds within PBCOC. Following the estimated dissolution preference, we anticipate that via a simple ultrasonication assisted process in deionized water, the Cs−Cl layer will be easily dissolved in water thus undergo a desalination process. The PBOC layers in its parental structure of PBCOC will be delaminated to form ultrathin layered materials as schematized in Fig. 1a. With this in mind, a simple ultrasonication process has been employed by loading PBCOC in water. Significant broadening peaks are observed in the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern as shown in Fig. 1b for the obtained layered PBOC materials, indicating the layer thickness decreases compared with the original PBCOC bulk material35. The diffraction pattern evolution suggests that a crystallographic structure transition has been involved during the desalination process. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging with the corresponding height profiles double confirms that the as-synthesized ultrathin PBOC sheets exhibit an average thickness of 3.2 nm (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, due to the thinner thickness of the obtained material, the Brunauer Emmett Teller (BET) specific surface area (Supplementary Fig. 2) of PBOC increases to 2.561 m2 g−1, which is 4.3 times larger than that of the original bulk PBCOC (0.5963 m2 g−1) as measured by N2 adsorption and desorption isotherms. Interestingly, when referring to CO2 isotherm, PBOC only exhibits a slightly larger CO2 BET surface area (2.587 m2 g−1) than that of PBCOC (1.953 m2 g−1), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, which could be ascribed to the existence of surface Cs+ in the parental structure PBCOC. The adsorbed Cs+ tend to condense CO2 molecules on the bulk material surface thus contributing to a more significant CO2 adsorption capacity36,37.

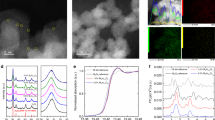

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) with its corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5, Fig. 2a−f and Supplementary Table 1) are employed to confirm the morphology and overall elemental distribution in the original bulky PBCOC and the obtained ultrathin PBOC, respectively. Compared with PBCOC, the atomic concentration of Cs in PBOC is lowered down to 0.05%; carefully check the STEM-EDS spectra of PBOC as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, the characteristic Cs L lines are fully immersed within the background noise, which suggests that the Cs+ concentration of 0.05% indexed in the STEM-EDS mapping can be neglectable. Also, the atomic concentration of Cl has been reduced to 21.73%, suggesting that the Cs+ and Cl− do undergo a leaching process during the desalination process. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), including the survey and high-resolution Bi 4f, Pb 4f, O 1s, and Cl 2p spectra, are shown in Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 7. The disappearance of Cs+ in PBOC after Cs−Cl desalination can be confirmed by the XPS survey spectrum. The valence states of Bi 4f, Pb 4f, O 1s, and Cl 2p remain unchanged38, although the binding energies slightly shift to a higher energy level similar to BiOCl39. This observation could be ascribed to the nature of the Cs−Cl desalination together with the structural rearrangement of the obtained layered structure. Besides, we applied the inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and anion chromatography (AC) to trace the dissolution process of PBCOC. The time-dependent concentrations of Cs+ and Cl− in deionized water solution show that almost 100% Cs+ and 30% of Cl− are dissolved from PBCOC after 42 h ultrasonic treatment (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Besides, we also used aqua regia to digest the resulting PBOC material. The molar ratio of Cs/Pb/Bi in PBOC has been determined to be 0.02738/5.719/14.00 by ICP-MS (Supplementary Fig. 8b), in which the molar ratio of Pb/Bi is close to the corresponding stoichiometric ratio of 0.6/1.4 in PBOC. The detected very trace amount of Cs+ might be accounted for the surface adsorption effects on the resulting ultrathin samples. These observations double confirm that the Cs−Cl has been removed from its precursor parental structure, and the resulting ultrathin layer shows a well-defined chemical formula of Pb0.6Bi1.4O2Cl1.4. The crystal structure of the as-synthesized ultrathin PBOC layers has been further analyzed with STEM and Le Bail refinement against PXRD. High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) and bright-field (BF) STEM images were taken to study the heavy atoms and light atoms arrangements for the as-synthesized PBOC. As shown in Fig. 2h, i, the layered stacking feature and the atomic arrangement can be directly observed from the inversed fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the atom-resolved Z-contrast HAADF-STEM (Fig. 2h) and BF-STEM (Fig. 2i) images as viewed along [100] zone axis. In the PBOC structure, four [Pb0.6Bi1.4O2Cl1.4] layers are stacking together via the ABBA fashion governed by a mirror symmetry with the internal two B layers sharing one layer of chlorine atoms. The B layers are stacking with the A layers via Van der Waals interaction. Based on this observation, a hypothetical crystal structure model can be proposed with a tetragonal unit cell of a = 4.0 Å and c = 27.4 Å. HAADF-STEM (Fig. 2j) and BF-STEM (Fig. 2k) images viewing along [111] axis double verify the lattice parameter for a axis is ~4.0 Å. A single-unit-cell-thickness structure model can be well imposed with the STEM observation. Moreover, we further employed the PXRD pattern for Le Bail refinement on the proposed structural model for PBOC. The final refinement has been converged to a structure model with space group I4/mmm, a = 3.895 Å and c = 27.186 Å (Supplementary Tables 2, 3). The deduced lattice parameters from PXRD are slightly smaller than that (4.0 Å and ~27.4 Å) as observed from the atom-resolved HAADF-STEM imaging, which could be ascribed to the boundary expansion effects of the ultrathin layers40. As shown in Fig. 2l, the experimental PXRD is consistent with the simulated pattern against the proposed structure mode. Due to the highly anisotropic morphology and preferential stacking of the ultrathin PBOC layers, the PXRD gives rise to a family of (00l) peaks ascribing to the ultrathin layered feature, which accounts for a slightly significant refinement convergence agreement factor41.

a−f STEM-EDS elemental-mapping images and the corresponding element atomic concentrations. g Bi 4f and Pb 4f spectra of ultrathin PBOC layer. h−k Atom-resolved inversed FFT HAADF- and BF- STEM images, with the labelled zone axis (O and Cl atoms are omitted for the sake of clarity in Fig. k). l Le Bail fitting results against PXRD pattern.

To further understand the driving force of the desalination process in PBCOC, we employed theoretical modelling technique to calculate the dissolution energy of Cs−Cl in PBCOC (reaction (1)). By dividing the overall reaction into two steps, as shown in reactions (2) and (3), the reaction energy of reaction (2) can be calculated with density functional theory (DFT). The reaction energy (3) can be referring to the enthalpies for CsCl (s) dissolution (∆solHθ: 17.78 kJ mol−1)42.

To account for fractional occupancy of Pb and simplify the calculation loading, here PbBi3CsO4Cl4 and PbBi3O4Cl3 were adopted to represent the PBCOC and PBOC. A 2 × 2 supercell was constructed, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. We find that up to 47.3 kJ energy is required to split up 1 mol CsCl (s) via the desalination reaction (2), whereas the dissolution of 1 mol CsCl (s) to form Cs+ (aq) and Cl− (aq) with a concentration of 1 mol L−1 is with uphill energy of 18.3 kJ. Therefore, the total reaction energy to drive the overall reaction is 65.6 kJ mol−1. Considering the power density of the applied ultrasonication is 0.1 W cm−2, when the time is long enough, the ultrasonic energy is sufficient to promote the desalination and delamination process, despite the uncertainty of the energy conversion efficiency. The above coarse modelling results are consistent with our experimental observations and further verify the feasibility of employing this top-down desalination strategy powdered by ultrasonication to synthesize PBOC from PBCOC.

Electronic structure and photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance

Benefiting from the ultrathin layered feature and rich exposed reconstructed bimetal oxyhalide surface, the ultrathin PBOC exhibits improved electronic structure and photoelectric properties compared with the bulk PBCOC. UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra displayed in Fig. 3a demonstrates that the bandgap of PBOC is 2.82 eV, which is narrower than its parental structure PBCOC (3.14 eV). Mott–Schottky measurement (Fig. 3b) was conducted to locate the conduction band minimums (CBM) or valence band maximums (VBM) for the ultrathin PBOC and bulk PBCOC. It can be observed that an N-type semiconductor feature is observed in these two materials with their flat-band potentials at −0.19 and −0.29 V, respectively. Accordingly, the experimental CBMs are determined to be at −0.34 and −0.44 V, respectively, since the flat band potential of N-type semiconductors is generally about 0.1 or 0.2 V more positive than its CBMs43. The electronic band structures versus NHE at pH 7 can be elucidated in Fig. 3c, which shows that the ultrathin PBOC displays a narrower bandgap than bulk PBCOC due to the potential shifts of both CBM and VBM. This tendency has also been confirmed by DFT calculation (Supplementary Fig. 17a and Fig. 17c). Furthermore, they both show appropriate band edge positions in their electronic structures, which is favourable for the catalytic CO2 reduction and O2 evolution reactions. Moreover, the electrochemical impendence spectroscopy (EIS) measurements (Fig. 3d) and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy results (Supplementary Fig. 10) reveal that PBOC exhibits higher electrical conductivity and lower emission response than PBCOC, especially under light radiation, indicating that PBOC is of improved charge transfer and carriers separation ability. The enhanced transient photocurrent densities in Fig. 3e and time-resolved fluorescence decay spectroscopy in Fig. 3f further confirm the accelerated photoexcited charge carrier transfer dynamics, in which the average lifetime increases from 1.59 ns (PBCOC) to 2.69 ns (PBOC), further suggesting the higher efficiency of charge separation under light irradiation with a slower recombination rate.

a UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra. Inset: corresponding optical images and obtained bandgaps of 2.82 and 3.14 eV, estimated by plotting (αhν)2 versus hν. α and ν are the absorbance and wavenumber; h is the Planck constant. b Mott−Schottky plots. c Schematic illustration of the electronic band structures; grey arrows represent the electron transition process under the light irradiation. CB, conduction band; VB, valence band. d Electrochemical impendence spectroscopy. e Transient photocurrent densities with light on/off cycles under full spectrum in 0.1 M Na2SO4 electrolyte solution at an applied potential of 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl electrode. f Time-resolved fluorescence spectra. Ave. τ is the average fluorescence lifetime.

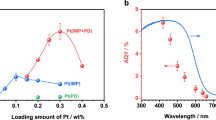

Inspired by the significantly improved light absorption, charge separation, and transfer abilities of ultrathin PBOC, it is promising to employ PBOC for photocatalytic CO2RR (Supplementary Fig. 11). As shown in Fig. 4a, apparent CO2 reduction performance, with reaction products of CO, CH3OH, and CH4, is achieved with respect to a pure CO2 concentration of 1500 ppm under the full spectrum irradiation with a standard Xe lamp. The dominant evolution products for CO and CH3OH are approximately 17.91 and 26.53 μmol g−1 within 4 h, which are 7.2 and 7.3 times higher than catalyzed by bulk PBCOC. Continuous O2 is also produced in the reaction system with a generation rate of ca. 48.69 μmol g−1 in 4 h (Supplementary Fig. 12a), which should be the oxidative product of H2O. The electrons involved in the reduction reaction are nearly equal to those participating in the oxidation process. Besides, ultrathin PBOC exhibits visible-light-induced photocatalytic CO2 reduction property (Supplementary Fig. 12b). Similar CO2RR activity was also detected using atmospheric air as a CO2 source under the entire solar spectrum, where the CO2 concentration in atmospheric air was measured to be 500 ppm with gas chronometry (GC) (Fig. 4b). This observation indicates the existence of oxidative O2 in the atmosphere does not influence the CO2 reduction performance on PBOC. Besides, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 12c, d, PBOC offers decent photocatalytic CO2 reduction activities under different CO2 concentrations (500, 1000, and 1500 ppm) and different seasons (Summer: 490−500 ppm CO2, 33.0 ± 0.5 °C, 42% humidity; Autumn: 500−510 ppm CO2, 22.0 ± 0.5 °C, 60% humidity), in which high temperature is more favourable to the process than high humidity. To confirm the origin of the carbon and oxygen sources in photocatalytic reaction, controlled experiments with 13C and 18O isotopic tracing were conducted and monitored with a gas chromatography-mass spectrometer (GC-MS) (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Figs. 13, 14). In the 13C isotopic tracing experiment, 13CO (m/z = 29), 13CH3OH (m/z = 33), 13CH4 (m/z = 17) and O2 (m/z = 18) are observed in the GC-MS spectrum; While in 18O isotopic tracing experiment, 18O2 (m/z = 36) is also detected. These results imply that the above products do convert from CO2 reacting with H2O. Throughout four cycles (16 h) tests, this ultrathin layered catalyst does not exhibit significant catalytic performance decay (Fig. 4d), and structure or composition degradation (Supplementary Fig. 15), which suggests a good photostability. As expected, the PBOC displays outstanding photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance over the bulk sample, mainly due to the considerable enhancement of charge separation efficiency, improved light absorption capability, and the declined energy barriers for CO2 reduction. Moreover, the photocatalytic CO2 reduction properties of PBOC also outperform the as-prepared BiOCl nanosheet (~4.35 nm, Supplementary Fig. 16) and many other state-of-the-art photocatalysts (Supplementary Table 6) under comparable conditions44, which could be ascribed to the unique interfacial and electronic structure induced by the mixing occupancy of Pb and Bi in ultrathin PBOC inherited from its parental structure.

a Photocatalytic CO2RR products under full-spectrum light irradiation. b Photocatalytic CO2 reduction activities of the ultrathin PBOC in N2 (grey ball), atmospheric CO2 (red ball), and pure CO2 (blue ball) under full-spectrum light irradiation. c GC-MS spectrum of the products with 13CO2. d CO2RR cycling measurements under full-spectrum light irradiation for 4 h. Error bars are means ± standard deviation of three replicates.

Structural insights of photocatalytic activity

To further understand the intrinsic photocatalytic CO2RR reaction dynamics on PBOC interface, DFT calculations were employed to calculate the electronic structure for the outer layer of the single-unit-cell PBOC layer. Interestingly, the co-occupied Pb contributes to a bandgap decrease compared with BiOCl (Supplementary Fig. 17b, c). Besides, the co-occupied Pb can induce a more significant polarization effect, thus promoting photoexcited charge separation and facilitating photocatalytic efficiency45. Furthermore, we conducted DFT calculations on a top-site surface model to simulate the charges behaviours and interaction with CO2 on PBOC (Supplementary Fig. 18). The model and the partial density of states (PDOS) are shown in Fig. 5a, b suggesting that the co-occupied Pb would induce a higher PDOS on meta-Bi atom at the conduction-band edge. The meta-Bi atom and Pb atom co-exhibit a robust electrostatic attraction towards C and O of the CO2 molecule, causing the O=C=O bending as confirmed by the differential charge density map in Fig. 5c. Mulliken population analysis of Pb atom and meta-Bi atoms (Fig. 5d, e) indicate that Pb can significantly suppress the electron donor of meta-Bi, resulting in a large decrease of Mulliken charge from 0.807 to 0.194. The meta-Bi atoms with affluent electron density exhibit a strong electrostatic attraction towards electrophilic carbon atoms in CO2 molecules (Fig. 5c). After binding with CO2, the high electron intensity around meta-Bi atom is neutralized, with the Mulliken charge increasing from 0.194 to 0.400 (Fig. 5f), revealing that electron transfer occurred between meta-Bi atom and CO2. The Pb atom plays a vital role in PBOC for the photogenerated charge separation and transfer in the photocatalytic CO2RR process, in which the CO2 molecules can be sufficiently adsorbed and activated (CO2 → *CO2), thus facilitating the subsequent reduction reactions.

a Lead–bismuth oxyhalide outer layer structural model and (b) the partial density of states (PDOS). c Isosurface of differential charge density. Mulliken population of (d) layer bismuth oxyhalide layer, e lead–bismuth oxyhalide outer layer and (f) lead–bismuth oxyhalide outer layer after CO2 adsorption. g Gibbs free energy calculations towards the reaction pathway and free energy diagrams. The grey, red and blue lines show the reaction pathway of CO2RR to CO, CH3OH, and CH4, respectively.

Based on the CO2 molecules activation process46,47, we further explore the CO2RR dynamics on the surface of ultrathin PBOC. Three typical possible reaction pathways of reducing CO2 to CO, CH3OH, and CH4 were considered (Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Tables 4, 5, and Fig. 5g), respectively. According to the detailed reaction pathways with the diagram illustrated in Fig. 5g, the CO2 on the ultrathin PBOC interface is initially activated to generate the adsorbed *CO2, which is subsequently energetically uphill transformed to *COOH and *CO. Afterwards, the transition from *CO to *CHO is thermodynamically favourable with an energy release of 0.651 eV, while the desorption of CO requires an energy of 0.262 eV. Thus, *CO is more feasible to be transformed into *CHO following pathway II or III. This explains the higher productivity of CH3OH and CH4 on ultrathin PBOC layers in CO2RR. Then, the reduction energy barrier from *CHO to *CHOH (pathway III) is much more significant than that to form *CH2O (pathway II), which is consistent with the observation of lower CH4 yield during the CO2RR process. Overall, the energy expenditure from *CHO to *CHOH (pathway III) is higher than that from *CO to CO (pathway I), further verifying the CO2RR yield ranking of CH3OH > CO > CH4, which is consistent with the experimental observations.

Discussion

Via a top-down desalination strategy, we have successfully unlocked the rich active bimetallic interface from its parental structure PBCOC. The as-synthesized ultrathin PBOC material exhibits a larger surface area with fruitful well-defined bimetallic catalytic centres, which enhanced the photocatalytic CO2RR performance in gas-phase reaction, with the atmospheric CO2 as gas source. Based on the insightful mechanistic study on the structural-property relationship, the unlocked rich catalytic sites, enhanced interlayer charge conductivity, and superior structural stability are critical factors contributing to the excellent CO2RR performance. The novel desalination strategy used to unlock the active intralayer interface and reactive centres, can be extended to fabricating other UTNs from their complicated parental structures that with covalent and ionic bonded layers co-existed. This work not only reports a novel, highly efficient ultrathin photocatalyst for atmospheric CO2 reduction and paves the way for the carbon-neutral global, but it also expands the avenue for designing and synthesizing other ultrathin 2D materials with complex compositions from the well-documented host structural matrixes for various applications.

Methods

Material synthesis

All the chemical reagents, including bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Aladdin, ACS, ≥98.0%), sodium chloride (Aladdin, AR, 99.5%), caesium chloride (Alfa Aesar, metals basis, 99.999%), lead oxide yellow (Aladdin, AR, 99.9%), and NaOH (Innochem, 99%), were used as purchased without further purification. The layered ultrathin BiOCl was synthesized via a hydrothermal route7. 1 mmol of Bi(NO3)3 ∙ 5H2O and 1 mmol of KCl were added in 15 mL distilled water with continuous stirring, and then 1 M NaOH solution was used to adjust the pH to neutral. After stirring for 30 min, the mixture was transferred to a 20 mL Teflon-lined stainless autoclave and heated at 160 °C for 24 h, then air-cooled to room temperature. PBCOC was synthesized via a solid-state chemical reaction under vacuum. 1.4 mmol (0.3647 g) BiOCl, 0.6 mmol (0.1339 g) PbO, and 0.6 mmol (0.1015 g) CsCl were weighted in an Ar-filled glovebox and grounded in a mortar for 30 mins. The well-grounded precursor powder was sealed in a 9 mm-diameter quartz ampoule. Then the ampoule was loaded into a programmable muffle furnace and heated to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1. The ampoule was maintained in the furnace at 800 °C for 5 days and naturally cooled down to room temperature. White PBCOC powders have been harvested. Afterwards, 1.0000 g of PBCOC was loaded in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask and mixed with 150 mL of deionized water. The mixture was periodically treated with an ultrasonic bath (80 Hz, 100 W) for 14 days (ultrasonicated for 3 h and swell on standing for 9 h, twice every day), ultrathin PBOC layers were harvested after filtering the resulted solution.

Characterization

PXRD patterns were recorded using a 9 KW Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The thickness measurement of the samples was performed on AC Mode AFM (Asylum Research, MFP-3D-Stand Alone). BET-specific surface areas of the as-synthesized materials were determined by N2 adsorption/desorption curve on a BELSORP-max machine. The morphology and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy study of PBCOC was performed on a Zeiss Merlin SEM operated at various acceleration voltages. The HAADF-STEM imaging and the corresponding EDS analyses of PBOC were performed on an FEI Titan Themis apparatus with an X-FEG electron gun and a DCOR aberration corrector operating at 300 kV. The bulky-like HAADF-STEM image was taken from an isotropic air-dried particle with multiple ultrathin layers aggregated together in the obtained PBOC sample. The XPS was implemented on a PHI 5000 Versaprobe III instrument (ULVAC-PHI, UK) to analyze the valence states of the elements with a monochromatic Al Kα source. The spectrum was analyzed by the PHI-MultiPak software, referencing C1s to 284.8 eV. The UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) of the powder samples were recorded on a UV–Vis-NIR spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Lambda 750S) equipped with an integrating sphere. BaSO4 powder was used as a reference. A RF-5301PC PL spectrofluorometer with an excitation wavelength of 200 nm was used to examine the charge recombination rate. The reduction products were analyzed with an Agilent GC-MS. The ions concentrations of PBCOC were determined by ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher iCAP RQ) and Anion Chromatography (Aquion, Thermo Fisher).

Photocatalytic CO2 reduction tests

Photocatalysis experiments were carried out in a custom-made glass vessel with a quartz glass cap (Perfectlight, China, Supplementary Fig. 11)37. A 300 W Xe lamp (Perfectlight, China) was used as the full spectrum light source, while the visible light source was obtained by employing a 420 nm filter to exclude the UV light from the full spectrum. The relatively low concentration of CO2 (ca.1500 ppm) used in the standard catalysis reaction was in situ generated by the reacting NaHCO3 with H2SO4 (volume ratio of concentrated H2SO4 and deionized water was 1:1). The in-house atmospheric air with a concentration of ca.500 ppm as characterized with GC was also used as a CO2 source for photocatalytic CO2RR. The detailed procedures were as follows: firstly, 25 mg of the photocatalyst was uniformly dispersed into 1 mL deionized water and then dried in a vessel at a 60 °C oven. Afterwards, 50 μL of deionized water was dropped onto the catalyst’s surface to construct a humid interface. Next, 500 mg NaHCO3 was added to a 200 mL of glass reaction chamber, followed by adding the above-prepared sample vessel on the top of NaHCO3 powder in the chamber. Subsequently, the reaction chamber was purged with pure N2 gas for 30 min to expel the air and then vacuumed for 15 min. Before light irradiation, 2 mL of H2SO4 was injected into the reaction chamber to start producing a low concentration of CO2. At a fixed interval period, 200 µL of the gas products were withdrawn and qualitatively analyzed with gas chromatography. The 13CO2 photoreduction experiment was also carried out in a customized glass vessel with the 13CO2 source produced by reacting NaH13CO3 with H2SO4.

Le bail refinement

Le Bail refinement was conducted to confirm the lattice parameters and crystal structure of PBOC using the GSAS-EXPGUI suite48. Here, the primary structural model of PBOC with a space group of I4/mmm was proposed from the atom-resolution HAADF-STEM imaging.

Solvation calculation

First-principles calculation was performed with DFT implanted in VASP at spin-polarized generalized gradient approximation (GGA) level49. PBE exchange-correlation functional and PAW pseudo potential were used. An energy cut-off of 520 eV was applied for the plane-wave basis set. The Brillouin zones were sampled by a 3 × 3 × 1 grid of Monkhorst-pack k points. All atoms were allowed to relax until the maxima force on the atoms was smaller than 0.02 eV Å−1.

DFT calculations

DFT calculation was performed using DMol3 code50,51. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional with GGA was utilized to describe the exchange-correlation energy52,53. Spin-polarization was included in all calculations, and a damped van der Waals correction was incorporated using Grimme’s scheme to describe the non-bonding interactions54. The density functional semi core pseudo potential (DSPP) was utilized to account for the relativistic effects of core electrons and the double numerical plus polarization (DNP) basis set55,56. The k-point of 4 × 4 × 2 and 2 × 2 × 1 were set for the bulk and slab model using the Monkhorst-Pack method, respectively.

To better evaluate the specific active catalytic site within PBOC, Bi-terminated Pb0.6Bi1.4O2Cl1.4 (001) in a 2 × 2 × 1 supercell was constructed to represent the out layer of PBOC, in which a top-site lead-bismuth oxyhalide layer with Pb proportion of 25% was modulated to replace the Pb/Bi mixing occupancy surface with Pb proportion of 30%, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 18.

To better simulate the experimental environment, a water solvation model (COSMO) with a dielectric constant of 78.54 was applied to mimic the aqueous condition. The change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) for each of the CO2RR steps was evaluated according to the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) model suggested by Nørskov and co-workers57,58. The Gibbs free energy was defined as:

where ΔEDFT is the electronic energy difference directly obtained from DFT calculation, ΔEZPE and TΔS are the zero-point energy correction and entropy change at T = 298.15 K, respectively. Here, the correction terms are present in Supplementary Table 4. Most of the corrections are from previous literature58,59. In addition, −0.41 eV correction was applied to the electronic energy of CO as the PBE functional cannot describe this molecule accurately58,60.

Data availability

All the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

References

Di, J., Xiong, J., Li, H. & Liu, Z. Ultrathin 2D photocatalysts: Electronic-structure tailoring, hybridization, and applications. Adv. Mater. 30, 1–30 (2018).

Xu, J., Chen, X., Xu, Y., Du, Y. & Yan, C. Ultrathin 2D rare-earth nanomaterials: Compositions, syntheses, and applications. Adv. Mater. 32, 1–17 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Surface strategies for catalytic CO2 reduction: From two-dimensional materials to nanoclusters to single atoms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 5310–5349 (2019).

Di, J., Xia, J., Li, H. & Liu, Z. Freestanding atomically-thin two-dimensional materials beyond graphene meeting photocatalysis: Opportunities and challenges. Nano Energy 35, 79–91 (2017).

Xia, P. et al. Designing defective crystalline carbon nitride to enable selective CO2 photoreduction in the gas phase. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1–9 (2019).

Zhang, K. L., Liu, C. M., Huang, F. Q., Zheng, C. & Wang, W. D. Study of the electronic structure and photocatalytic activity of the BiOCl photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B 68, 125–129 (2006).

Jiang, J., Zhao, K., Xiao, X. & Zhang, L. Synthesis and facet-dependent photoreactivity of BiOCl single-crystalline nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 4473–4476 (2012).

Wang, L., Wang, L., Du, Y., Xu, X. & Dou, S. X. Progress and perspectives of bismuth oxyhalides in catalytic applications. Mater. Today Phys. 16, 100294 (2021).

Cui, D., Wang, L., Du, Y., Hao, W. & Chen, J. Photocatalytic reduction on bismuth-based p-block semiconductors. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 15936–15953 (2018).

Shi, M. et al. Intrinsic facet‐dependent reactivity of well‐defined BiOBr nanosheets on photocatalytic water splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6590–6595 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. An excitonic perspective on low-dimensional semiconductors for photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 14007–14022 (2020).

Rossmeisl, J., Logadottir, A. & Nørskov, J. K. Electrolysis of water on (oxidized) metal surfaces. Chem. Phys. 319, 178–184 (2005).

Liang, L. et al. Single unit cell bismuth tungstate layers realizing robust solar CO2 reduction to methanol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 13971–13974 (2015).

Jin, X. et al. A bismuth rich hollow Bi4O5Br2 photocatalyst enables dramatic CO2 reduction activity. Nano Energy 64, 103955 (2019).

Chen, F. et al. Thickness-dependent facet junction control of layered BiOIO3 single crystals for highly efficient CO2 photoreduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1804284 (2018).

Wang, B. et al. Sacrificing ionic liquid-assisted anchoring of carbonized polymer dots on perovskite-like PbBiO2Br for robust CO2 photoreduction. Appl. Catal. B 254, 551–559 (2019).

Sridharan, K. et al. Advanced two-dimensional heterojunction photocatalysts of stoichiometric and non-stoichiometric bismuth oxyhalides with graphitic carbon nitride for sustainable energy and environmental applications. Catalysts 11, 426 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) photocatalytic nanomaterials: Applications for fuels and environmental management. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 254, 76–93 (2018).

Di, J. et al. Isolated single atom cobalt in Bi3O4Br atomic layers to trigger efficient CO2 photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–7 (2019).

Huang, H. et al. Macroscopic polarization enhancement promoting photo- and piezoelectric-induced charge separation and molecular oxygen activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 11860–11864 (2017).

Wu, J. et al. Efficient visible-light-driven CO2 reduction mediated by defect-engineered BiOBr atomic layers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8719–8723 (2018).

Li, J., Zhan, G., Yu, Y. & Zhang, L. Superior visible-light hydrogen evolution of Janus bilayer junctions via atomic-level charge flow steering. Nat. Commun. 7, 11480 (2016).

Zhou, J. et al. A library of atomically thin metal chalcogenides. Nature 556, 355–359 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Elastic properties of 2D ultrathin tungsten nitride crystals grown by chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1–7 (2019).

Tan, C. & Zhang, H. Wet-chemical synthesis and applications of non-layer structured two-dimensional nanomaterials. Nat. Commun. 6, 7873 (2015).

Li, J., Wu, X., Pan, W., Zhang, G. & Chen, H. Vacancy-rich monolayer BiO2−x as a highly efficient UV, visible, and near-infrared responsive photocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 491–495 (2018).

Yi, M. & Shen, Z. A review on mechanical exfoliation for the scalable production of graphene. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 11700–11715 (2015).

Li, H., Wu, J., Yin, Z. & Zhang, H. Preparation and applications of mechanically exfoliated single-layer and multilayer MoS2 and WSe2 nanosheets. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1067–1075 (2014).

Stark, M. S., Kuntz, K. L., Martens, S. J. & Warren, S. C. Intercalation of layered materials from bulk to 2D. Adv. Mater. 31, 1–47 (2019).

Anasori, B., Lukatskaya, M. R. & Gogotsi, Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16098 (2017).

Ran, J. et al. Ti3C2 MXene co-catalyst on metal sulfide photo-absorbers for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen production. Nat. Commun. 8, 13907 (2017).

Wang, B. et al. Revealing the role of oxygen vacancies in bimetallic PbBiO2Br atomic layers for boosting photocatalytic CO2 conversion. Appl. Catal. B 277, 119170 (2020).

Charkin, D. O. et al. A novel family of layered bismuth compounds. J. Solid State Chem. 147, 527–535 (1999).

Dean, J. A. Lange’s Handbook Of Chemistry 15th edn (McGraw-Hill, 1999).

Ungár, T. Microstructural parameters from X-ray diffraction peak broadening. Scr. Mater. 51, 777–781 (2004).

Lide, D. R. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 101st edn (CRC Press, 2020).

Wu, X. et al. Photocatalytic CO2 conversion of M0.33WO3 directly from the air with high selectivity: Insight into full spectrum-induced reaction mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5267–5274 (2019).

Deng, P. et al. Bismuth oxides with enhanced bismuth–oxygen structure for efficient electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to formate. ACS Catal. 10, 743–750 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Boosting visible-light-driven photo-oxidation of BiOCl by promoted charge separation via vacancy engineering. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 3010–3017 (2019).

Bao, W. et al. Controlled ripple texturing of suspended graphene and ultrathin graphite membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 562–566 (2009).

Smith, A. I. et al. Alkali metal intercalation and reduction of layered WO2Cl2. Chem. Mater. 32, 10482–10488 (2020).

Johnson, G. K. & Gayer, K. H. The enthalpies of solution and formation of the chlorides of cesium and rubidium. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 11, 41–46 (1979).

Li, X. et al. Engineering heterogeneous semiconductors for solar water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 2485–2534 (2015).

Zhang, L., Wang, W., Jiang, D., Gao, E. & Sun, S. Photoreduction of CO2 on BiOCl nanoplates with the assistance of photoinduced oxygen vacancies. Nano Res 8, 821–831 (2015).

Li, H. et al. Enhanced ferroelectric-nanocrystal-based hybrid photocatalysis by ultrasonic-wave-generated piezophototronic effect. Nano Lett. 15, 2372–2379 (2015).

Nguyen, T. N. et al. Fundamentals of electrochemical CO2 reduction on single-metal-atom catalysts. ACS Catal. 10, 10068–10095 (2020).

Li, Y., Li, B., Zhang, D., Cheng, L. & Xiang, Q. Crystalline carbon nitride supported copper single atoms for photocatalytic CO2 reduction with nearly 100% CO selectivity. ACS Nano 14, 10552–10561 (2020).

Larson A. C. & Dreele, R. B. V. General Structure Analysis System (GSAS). Los Alamos National Laboratory Report LAUR 86-748 (Los Alamos Natl. Lab., 2004).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Delley, B. An all-electron numerical method for solving the local density functional for polyatomic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 92, 508–517 (1990).

Delley, B. From molecules to solids with the DMol3 approach. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 7756–7764 (2000).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7413–7421 (1999).

Du, A. et al. Hybrid graphene and graphitic carbon nitride nanocomposite: Gap opening, electron–hole puddle, interfacial charge transfer, and enhanced visible light response. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 4393–4397 (2012).

Delley, B. Hardness conserving semilocal pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 66, 155125 (2002).

Liu, P. & Rodriguez, J. A. Catalysts for hydrogen evolution from the [NiFe] hydrogenase to the Ni 2P (001) surface: The importance of ensemble effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14871–14878 (2005).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Peterson, A. A., Abild-Pedersen, F., Studt, F., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. How copper catalyzes the electroreduction of carbon dioxide into hydrocarbon fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1311–1315 (2010).

Karamad, M., Hansen, H. A., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. Mechanistic pathway in the electrochemical reduction of CO2 on RuO2. ACS Catal. 5, 4075–4081 (2015).

Yang, W. et al. Tailoring crystal facets of metal–organic layers to enhance photocatalytic activity for CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 409–414 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21777045, H.C.), National Key Research and Development Programme of China (2021YFA1202500, H.C.), Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Interfacial Science and Engineering of Materials (ZDSYS20200421111401738, H.C.), Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar of Guangdong Province, China (2020B151502094, H.C.), and Foundation of Shenzhen Science, Technology and Innovation Commission (SSTIC) (JCYJ20200109141625078, H.C.; JCYJ20190809144409460, R.Z.). We acknowledge the technical support from the SUSTech Core Research Facilities and Centre for Computational Science and Engineering at Southern University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.F. and R.Z. contributed equally to this work. H.C. and X.F. conceived the idea, designed the experiments. X.F. fabricated the materials and contributed to the atomic-resolution STEM imaging. C.G. and X.W. performed the photocatalytic CO2RR experiments, the isotopic experiments, and the photoelectric properties measurements. R.Z. and Y.J. contributed to the DFT calculations. W.W. conducted the electrochemical measurements. W.Z., R.W., and S.Y. carried out the SEM, XPS, and AFM measurements, respectively. J.P. conducted the Le Bail refinement. X.F. wrote the manuscript. H.C. and X.W. supervised the work and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the manuscript revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jiexiang Xia, Mingshan Zhu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, X., Zheng, R., Gao, C. et al. Unlocking bimetallic active sites via a desalination strategy for photocatalytic reduction of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Nat Commun 13, 2146 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29671-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29671-0

This article is cited by

-

Progress in design and preparation of multi-atom catalysts for photocatalytic CO2 reduction

Science China Materials (2024)

-

A review on Bi2WO6-based photocatalysts synthesis, modification, and applications in environmental remediation, life medical, and clean energy

Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering (2024)

-

Photocatalytic CO2 reduction

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.