Abstract

Van der Waals magnets have emerged as a fertile ground for the exploration of highly tunable spin physics and spin-related technology. Two-dimensional (2D) magnons in van der Waals magnets are collective excitation of spins under strong confinement. Although considerable progress has been made in understanding 2D magnons, a crucial magnon device called the van der Waals magnon valve, in which the magnon signal can be completely and repeatedly turned on and off electrically, has yet to be realized. Here we demonstrate such magnon valves based on van der Waals antiferromagnetic insulator MnPS3. By applying DC electric current through the gate electrode, we show that the second harmonic thermal magnon (SHM) signal can be tuned from positive to negative. The guaranteed zero crossing during this tuning demonstrates a complete blocking of SHM transmission, arising from the nonlinear gate dependence of the non-equilibrium magnon density in the 2D spin channel. Using the switchable magnon valves we demonstrate a magnon-based inverter. These results illustrate the potential of van der Waals anti-ferromagnets for studying highly tunable spin-wave physics and for application in magnon-base circuitry in future information technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Van der Waals magnets are recently discovered magnetic materials with covalent bonding within the two-dimensional atomic layers and van der Waals interactions between the layers1,2,3. Owing to the short-range nature of magnetic exchange interaction, van der Waals magnets usually have weak interlayer exchange coupling strengths4, making the spin system highly two-dimensional and susceptible to external perturbations5. Therefore, 2D magnons, quanta of spin waves propagating in van der Waals magnets, are highly tunable collective modes that are of great interest in fundamental science6,7,8,9 and are potentially technologically useful10,11,12. To harness static spin configurations and dynamic spin excitations for potential technological applications, spin valves, and magnon valves are two respective crucial types of devices13,14. Recently, spin valves based on van der Waals crystals with a high on–off ratio15,16 and electrical switchability17,18 have been demonstrated. The electrically switchable van der Waals magnon valve without varying external magnetic field, however, has yet to be realized.

Owing to the wave nature of magnons, creating “1” in a magnonic circuit (e.g., a state with finite signal) is relatively trivial, while creating “0” (e.g., a state with zero signal) is not. Using two diffusive magnon streams with the same magnitude and opposite directions, it is possible to create “0” at the detector electrode19. However, such an operation is closer to signal mixing rather than gating. On the other hand, making use of the concept of “gating” from the charge-based field effect transistor, it has been shown that the magnon conductivity of thin films of three-dimensional (3D) ferrimagnetic insulator yttrium iron garnet could indeed be tuned by passing a current through a strong spin-orbit coupling metal gate electrode14. The state of the art of such 3D magnon valve can achieve up to ~13% signal modulation14, which still falls short in terms of tunability. In this article, we report the realization of van der Waals magnon valves with 100% tunability using thin flakes of van der Waals antiferromagnetic insulator MnPS3.

Results

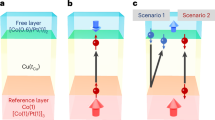

MnPS3 belongs to a class of layered antiferromagnetic insulators with chemical composition as XPSy (X = Fe, Cr, Mn, Ni; y = 3, 4)20,21,22. It has an energy bandgap of ~3.0 eV for bulk crystals23 with an easy axis mostly perpendicular to the sample plane22. Within each layer, the manganese atoms form a hexagonal structure and the localized spin of ~5.9 μB on each manganese atom has antiferromagnetic exchange interaction with its nearest neighboring manganese atoms22,24, as shown in Fig. 1a. Between the layers, each manganese atom has its spin aligned in the same direction with the two manganese atoms directly below and above it. The ratio between in-plane and out-of-plane exchange coupling for the nearest neighbor Mn atoms is ~405:124, making the magnons in MnPS3 highly two-dimensional.

a Atomic model of the crystal and spin structures of antiferromagnetic insulator MnPS3. b Atomic force micrograph of an MnPS3 magnon valve device. The injector, gate, and detector electrodes are marked by dark green, red, and blue. c Artistic schematics of the thermal magnon generation, manipulation, and detection. The upper left section shows the device structure with external circuits and direction of the external in-plane magnetic field; the lower right section shows propagation and modification of spin waves by the gate. Specifically, Iin: AC injection current; Igate: DC gate current; V2ω: the second harmonic thermal magnon inverse spin Hall signal; θ: the angle of the in-plane magnetic field with respect to the x direction.

Figure 1b shows the atomic force micrograph of a typical MnPS3 magnon valve device. The magnon valve constitutes the channel material MnPS3, an injector, a gate electrode, and a detector. The thickness of the particular MnPS3 channel is measured to be 12 nm and all electrodes are made of 250 nm wide and 9 nm thick platinum wires. A low-frequency AC current Iin is applied to the injector that locally heats up the MnPS3 crystal and thermally generates diffusive magnons. An in-plane magnetic field is applied that has a component perpendicular to the platinum detector electrode (defined as the x direction, see Fig. 1c) in order to tilt the out-of-plane spins towards such direction. In this configuration, the magnons would carry magnetic moments that can generate a second harmonic nonlocal voltage \({V}_{2\omega }\) at the platinum detector electrode via the inverse spin Hall effect10,25. An additional platinum electrode is fabricated between the injector and detector to act as a gate. We use a DC current Igate applied through the gate electrode to control the signal at the detector. The schematics of the thermal magnon generation, manipulation, and detection are shown in Fig. 1c.

Figure 2a shows the magnetic field angle-dependent \({V}_{2\omega }\) of a MnPS3 magnon valve at T = 2 K. Here the gate electrode is electrically floating and no current is applied to it. The root mean square value of the injector current \({I}_{{in}}\) is 100 μA with a frequency of 18.07 Hz. The external magnetic field of 9 T is applied in-plane with an angle θ (θ = 0 when H is along the x direction, as shown in Fig. 1c). The red solid line in Fig. 2a is a fit to a cosine function. It can be seen that the \({V}_{2\omega }(\theta )\) data fits to the cosine function well with a 2π periodicity and a maximum value at \(\theta =0\), consistent with previous studies on thermal magnons10,26. We simplify \({V}_{2\omega }(\theta =0)\) as \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) in following description. Figure 2b shows the temperature dependence of the \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\). It can be seen that V2ω,0 does not appear until the sample is below 20 K, while the Néel temperature of MnPS3 is around 80 K21, consistent with previous study26. A recent study on thermal magnons in layered ferromagnet CrBr3 also shows similar behavior27. The inset in Fig. 2b shows a close up of the rising and saturation behavior of \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) at low temperature.

a V2ω as a function of the angle θ between the external magnetic field B and the x direction. Here angle θ is determined the same as shown in Fig. 1c. b Temperature dependence of V2ω at θ = 0 (V2ω,0). (Inset: zoom-in view of V2ω,0 low-temperature behavior). c V2ω,0 versus the square of the injection current \({I}_{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}^{2}\). d V2ω,0 versus B at different Iin.

Figure 2c shows the dependence of \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) as a function of Iin at the injection electrode, which has a quadratic dependence \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\propto {I}_{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}^{2}\) for Iin < 80 μA, as expected for signal from thermally generated magnons. The deviation from the quadratic relationship at Iin > 80 μA could be attributed to the increase of the sample temperature in the channel at the detector electrode. Figure 2d shows \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) on B with different Iin. \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) initially increases linearly with B. This is consistent with the fact that the canting of the spins along the x direction is proportional to B, when B is small compares to the effective magnetic field of 106 T for the exchange interactions between the nearest neighboring Mn atoms28. At higher B, \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) declines slightly, and the peak of \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) appears to monotonically increase to higher B at higher Iin, which could be owing to a suppression of the magnon diffusion length by external magnetic field29. It is worth noting that magnons injected by exchange interactions are absent (i.e., there is zero first harmonic nonlocal signal \({V}_{1\omega }(\theta )\) with a π periodicity to the angle of the in-plane magnetic field) in our MnPS3 devices (see Supplementary Fig. S6), which is consistent with previous studies26.

We now turn to the gating effect on the thermal magnon signal \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) with B along the x direction. Figure 3a shows a typical dependence of the \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) on the DC gate current Igate. First, it can be seen that \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) is an even function of Igate, e.g., the effects of +Igate and −Igate are identical. Second, there exists a shut-off gate current Igate = I0 that could completely suppress \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\). Remarkably, for Igate = I0, \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) become negative, and for a sufficiently large gate current \({I}_{{gate}}={I}_{0}^{{\prime} }\), \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) tends to zero from the negative side. This means that the thermal magnon signal at the detector can be completely turned off by the gate, at two different values of Igate, which is \({I}_{0}\) and \({I}_{0}^{{\prime} }\). The existence of two zero points at the V2ω,0 (Igate) curve could be particularly useful for magnon logic operations. Among the two zero points, \({I}_{0}\) is more favorable since it is smaller and energetically more efficient.

Figure 3b shows the magnetic field angle-dependent \({V}_{2\omega }(\theta )\) for different Igate. The \({V}_{2\omega }(\theta )\) curves change sign between the two Igate ranges: \(0 < {I}_{{gate}} < {I}_{0}\) and \({I}_{0} < {I}_{{gate}} < {I}_{0}^{{\prime} }\). Furthermore, the \({V}_{2\omega }\) signal at \({I}_{{gate}}={I}_{0}\) and \({I}_{{gate}}={I}_{0}^{{\prime} }\) are suppressed completely for every angle θ. Such experimental observation proves that: (1) the sign reversal of \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) observed in Fig. 3a can be completely attributed to the thermal magnon signal of the device; (2) the zero points of \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\left({I}_{{gate}}\right)\) observed in Fig. 3a are indeed zero points of the magnitude of the second harmonic magnon signal. Additional experiment and finite element analysis have also been carried out to rule out the possibility of a local spin Seebeck effect or an anomalous Nernst effect in our devices (details in Supplementary Information S9–S11). If one put \({V}_{2\omega }\) in a complex coordinate system (e.g., in the x+iy plane, where i is the imaginary unit), \({V}_{2\omega }\) initially located at the positive side of the y axis with zero gate; as the gate current increases, \({V}_{2\omega }\) continuously move to the origin along the y axis, reaching the origin at \({I}_{{gate}}={I}_{0}\), and continue to move towards the negative side of the y axis with a larger gate; with large enough gate current, e.g., \({I}_{{gate}}={I}_{0}{\prime}\), \({V}_{2\omega }\) asymptotically moves back to the origin of the complex 2D plane.

By repeatedly applying Igate = 0 and Igate = 150 μA, \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) toggles between 196 nV (On state) and 0 nV (Off state), as shown in Fig. 3c. This demonstrates that the magnon valve can be electrically switched on and off without changing B. Such a fully electrical switching of the magnon signal lays the foundation of complex magnonic applications, such as logic gates that mimic those built from the charge-based transistors. In fact, Fig. 3c already illustrates the operation of a diffusive magnon-based NOT gate, which shows finite output (\({V}_{2\omega ,0}=196{{{{{\rm{nV}}}}}}\)) at zero input (Igate = 0) and zero output (\({V}_{2\omega ,0}=0\), here “0” means below the noise floor of our measurement system, which is < 1 nV) at finite input (Igate = 150 μA).

In order to understand the gate-dependent behavior of \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\), it is necessary to look into the general form of the inverse spin Hall voltage VISHE at the detector electrode, which contains \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) as it is excited by an AC current of frequency \(\omega\). VISHE is proportional to the non-equilibrium magnon accumulation nmag at the detector-MnPS3 interface30,31:

Here, gmix is the spin mixing conductance at the detector-MnPS3 interface which can be considered as a constant for our experimental conditions32. The non-equilibrium magnon accumulation nmag is caused by the thermally driven magnon spin current \({{{{{{\bf{J}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{m}}}}}}}\) along the x direction due to the Joule heating from the injector and the gate, which in turn is proportional to the lateral temperature gradient in the MnPS3 plane via the spin Seebeck effect33,34,35,36:

where the \(2\times 2\) spin Seebeck coefficient tensor \({{{{{\bf{S}}}}}}\) is defined within the MnPS3 plane and is given below in Eq. (3). Since the temperature increase near the detector is proportional to the Joule heating from current applied in the injector and the gate, the magnon temperature \({T}=2K+\beta \left(\alpha {I}_{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}^{2}+{I}_{{gate}}^{2}\right)\), where 2 K is the base temperature for the sample, and \(\beta \left(\alpha {I}_{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}^{2}+{I}_{{gate}}^{2}\right)\) accounts for the temperature increase due to the Joule heating from the injector and the gate. Here \(\alpha\, < \, 1\) is a dimensionless geometrical factor to count for a larger distance of the injector than the gate to the detector, and \(\beta\) is a constant involving the resistance of Pt bar and the specific heat of MnPS3. The lateral temperature gradient \({{{{{\boldsymbol{\nabla }}}}}}{{{{{\bf{T}}}}}}\) has a similar proportionality as \({{{{{\boldsymbol{\nabla }}}}}}{{{{{\bf{T}}}}}}\propto \beta (\alpha {I}_{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}^{2}+{I}_{{gate}}^{2})\hat{{{{{{\bf{x}}}}}}}\).

The spin Seebeck coefficient tensor \({{{{{\bf{S}}}}}}\) in MnPS3 under in-plane magnetic field can be derived based on a semi-classical Boltzmann transport theory of 2D magnons (details at Supplementary information S3 and S4)33:

where \({\eta }_{j,k}=1/{\tau }_{j,k}\), \(\hslash {\omega }_{j}\left({{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}\right)\) and \({{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{j}}}}}}}\left({{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}\right)\) are the magnon scattering rate, dispersion relation, and group velocity, respectively, for the jth magnon branch at magnon momentum k; \(\psi\) is the canting angle of the spins from its easy axis at finite in-plane magnetic field, and \({{\sin }}\psi {{\cosh }}{\xi }_{j}\) is the x-component spin polarization of magnon density of the jth magnon branch (see Supplementary information S4).

Therefore, VISHE can be regarded as a function of \(\beta \left(\alpha {I}_{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}^{2}+{I}_{{gate}}^{2}\right)\), and the temporal dependence of VISHE comes purely from the time variation of \({I}_{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}^{2}(t)\). Obviously, the temperature gradient \({{{{{\boldsymbol{\nabla }}}}}}{{{{{\bf{T}}}}}}\) increases monotonically with \(\beta \left(\alpha {I}_{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}^{2}+{I}_{{gate}}^{2}\right)\). The behavior of the spin Seebeck coefficient \({{{{{\bf{S}}}}}}\left(T\right)\) as shown in Eq. (3) is not so simple, but qualitatively \({{{{{\bf{S}}}}}}\left(T\right)\) should decrease as function of \(\beta \left(\alpha {I}_{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}^{2}+{I}_{{gate}}^{2}\right)\), because the elevated temperature would strongly reduce the magnon mean-free length. Consequently, the thermally driven magnon spin current \({{{{{{\bf{J}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\bf{m}}}}}}}\) will first increase, and then decrease with a general input current. In our real-time lock-in measurement, the first part will give a positive signal since more magnons are accumulating below the detector electrode with a non-zero input from the injection electrode. While in the second decreasing part, less magnons are accumulating below the detector electrode with applying the injection current, which equals to magnons flowing away from the detector electrode, resulting in a negative signal according to ISHE. The simulated functional dependence of VISHE, \({{{{{\bf{S}}}}}}\left(T\right)\) and \({{{{{\boldsymbol{\nabla }}}}}}{{{{{\bf{T}}}}}}\) on a general input current can be found in Supplementary Fig. S4a; the temporal dependence and the frequency distribution of VISHE under an AC excitation are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4b and S4c, respectively.

With the above discussion, we arrive at the following equation from which the performance of the magnon valve devices at different Iin and Igate can be simulated out of three global parameters:

where \(C\), \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) are the three global parameters, and \({\left[{\ldots}\right]}_{2\omega }\) means taking the second harmonic component.

Figure 4 shows the simulated \({V}_{2\omega ,0}{vs}.{I}_{{gate}}\) curves with Iin = 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 μA and \({{{{{\bf{B}}}}}}=4{{{{{\rm{T}}}}}}\) together with the experimental \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) data under the same operation conditions. With just three global parameters in Eq. (4) (C, \(\alpha\), and \(\beta\)), the simulation reproduces very well the experimental observation, including the naturally inferred symmetric \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\) for ±Igate, the magnitude of \({V}_{2\omega ,0}{vs}.{I}_{{gate}}\) under different Iin, as well as the values of the zero point of \({V}_{2\omega ,0}\), e.g., I0 and \({I}_{0}^{{\prime} }\) vs different Iin. The values of the global parameters \(C=1.05\times {10}^{-26}{{{{{\rm{V}}}}}}\cdot {{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}/{{\hslash }}\), \(\alpha =0.25\) and \(\beta =1.69\times {10}^{-4}{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}/{{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}{{{{{{\rm{A}}}}}}}^{2}\) are consistent with our experimental configuration, as detailed in Supplementary information S5. Furthermore, the simulation gives vanishingly small first harmonic response \({V}_{1\omega ,0}\), which agrees with the physics of thermal magnon excitation and it is indeed what we observed experimentally (see Supplementary Fig. S6). The above agreement between the simulation and the experimental data suggests that our model captures the physical trends behind the switching behavior of the MnPS3 magnon valves. The zero points at the thermal magnonic signal is guaranteed from our general argument, which comes from the highly tunable magnon spin current of the van der Waals antiferromagnetic insulators via electrical means. It is interesting to note that the first zero crossing point I0 is a weak function of the injection current Iin, as can be seen in Fig. 4, which can be understood as the consequence of the steep initial slop and sharp peak of the inverse spin Hall voltage VISHE with an input current (as can be seen in Supplementary Fig. S4a). Indeed, the simulated zero crossing point I0 also reveals its weak but finite dependence on the injection current Iin (Supplementary Fig. S8). It is also worth noting that, albeit good overall agreement is found between the experimental data and theoretical simulation with only three global parameters, appreciable difference between the experiment and simulation is found for small Igate (i.e., Igate < 50 μA), which hints the existence of additional factors and warrants further study.

In conclusion, electrically controlled MnPS3-based magnon valves have been realized, in which the second harmonic magnon signal can be turned off by DC current through a metal gate. Such a zero crossing demonstrates a complete blocking of the transmission of the second harmonic magnon signal, enabled by the nonlinear gate dependence of the non-equilibrium magnon density of the van der Waals antiferromagnetic crystal. We expect that other van der Waals antiferromagnetic insulators with weak interlayer interactions would have very similar properties. Such strong and reversible electrical control of the magnon signal demonstrates the potential of van der Waals insulators with magnetic orders and paves the way to application of magnonics in future digital circuits.

Methods

Device fabrication and sample characterization

MnPS3 flakes are mechanically exfoliated from bulk crystals and deposited on 300 nm SiO2/Si substrates. Thickness of the MnPS3 flakes used in our study ranges from 10 nm to 30 nm. The injector, gate and detector electrodes in the magnon valves are fabricated with standard electron-beam lithography, platinum deposition and lift-off processes. Platinum is deposited in a magnetron sputtering system, and the width of the wires is ~250 nm with a thickness of 9 nm. Afterwards, 5 nm of titanium and 80 nm of gold are patterned to contact the platinum wires. Twelve devices (device 1–12) were made and studied. Data shown in the main text were obtained from device 1 (Fig. 1–3) and device 2 (Fig. 4), and the results for other devices are presented in the Supplementary Information.

Nonlocal magnon transport measurement

The magnon transport measurement in MnPS3 is done in a physical properties measurement system (PPMS) with low-frequency lock-in amplifier technique. The injection AC current (18.07 Hz) in the range from 0 μA to 100 μA is provided by lock-in amplifier (NF LI5640) or a signal generator (Tektronix AFG 3000) with a 10KΩ resistor. Lock-in amplifiers (Stanford Research SR830) are used to probe the nonlocal voltages. Low noise voltage preamplifiers (NF LI75A) are also used. A voltage source (Keithley 2400) with a 100KΩ resistor is used to provide the DC current (0 μA~500 μA) to modulate the nonlocal signal. The temperature of the measurement in PPMS ranges from 2 K to 300 K, the applied magnetic field is parallel to our sample plane and the maximum field is 9 T.

Data availability

Data for figures that support the current study are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GLESFN. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Numerical simulations were performed with Mathematica. Source codes in Mathematica file format are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Huang, B. et al. Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature 546, 270–273 (2017).

Gong, C. et al. Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature 546, 265–269 (2017).

Deng, Y. et al. Gate-tunable room-temperature ferromagnetism in two-dimensional Fe3GeTe2. Nature 563, 94–99 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Determining the phase diagram of atomically thin layered antiferromagnet CrCl3. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 1116–1122 (2019).

Klein, D. R. et al. Enhancement of interlayer exchange in an ultrathin two-dimensional magnet. Nat. Phys. 15, 1255–1260 (2019).

Cenker, J. et al. Direct observation of two-dimensional magnons in atomically thin CrI3. Nat. Phys. 17, 20–25 (2020).

Zhang, X. X. et al. Gate-tunable spin waves in antiferromagnetic atomic bilayers. Nat. Mater. 19, 838–842 (2020).

Stepanov, P. et al. Long-distance spin transport through a graphene quantum Hall antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 14, 907–911 (2018).

Wei, D. S. et al. Electrical generation and detection of spin waves in a quantum Hall ferromagnet. Science 362, 229–233 (2018).

Cornelissen, L. J. et al. Long-distance transport of magnon spin information in a magnetic insulator at room temperature. Nat. Phys. 11, 1022–1026 (2015).

Chumak, A. V., Vasyuchka, V. I., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Magnon spintronics. Nat. Phys. 11, 453–461 (2015).

Khitun, A., Bao, M. Q. & Wang, K. L. Magnonic logic circuits. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 43, 264005 (2010).

Xiong, Z. H., Wu, D., Vardeny, Z. V. & Shi, J. Giant magnetoresistance in organic spin-valves. Nature 427, 821–824 (2004).

Cornelissen, L. J., Liu, J., van Wees, B. J. & Duine, R. A. Spin-current-controlled modulation of the magnon spin conductance in a three-terminal magnon transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 097702 (2018).

Song, T. et al. Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in spin-filter van der Waals heterostructures. Science 360, 1214–1218 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Very large tunneling magnetoresistance in layered magnetic semiconductor CrI3. Nat. Commun. 9, 2516 (2018).

Xu, J. et al. Spin inversion in graphene spin valves by gate-tunable magnetic proximity effect at one-dimensional contacts. Nat. Commun. 9, 2869 (2018).

Jiang, S. et al. Controlling magnetism in 2D CrI3 by electrostatic doping. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 549–553 (2018).

Ganzhorn, K. et al. Magnon-based logic in a multi-terminal YIG/Pt nanostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 022405 (2016).

Pei, Q. L. et al. Spin dynamics, electronic, and thermal transport properties of two-dimensional CrPS4 single crystal. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 043902 (2016).

Long, G. et al. Persistence of magnetism in atomically thin MnPS3 crystals. Nano Lett. 20, 2452–2459 (2020).

Joy, P. A. & Vasudevan, S. Magnetism in the layered transition-metal thiophosphates MPS3 (M=Mn, Fe, and Ni). Phys. Rev. B 46, 5425–5433 (1992).

Kargar, F. et al. Phonon and thermal properties of quasi-two-dimensional FePS3 and MnPS3 antiferromagnetic semiconductors. ACS Nano 14, 2424–2435 (2020).

Wildes, A. R., Roessli, B., Lebech, B. & Godfrey, K. W. Spin waves and the critical behaviour of the magnetization in MnPS3. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 10, 6417–6428 (1998).

Saitoh, E., Ueda, M., Miyajima, H. & Tatara, G. Conversion of spin current into charge current at room temperature: Inverse spin-Hall effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 182509 (2006).

Xing, W. Y. et al. Magnon transport in quasi-two-dimensional van der waals antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. X 9, 011026 (2019).

Liu, T. et al. Spin caloritronics in a CrBr3-based magnetic van der Waals heterostructure. Phys. Rev. B 101, 205407 (2020).

Okuda, K. et al. Magnetic-properties of layered compound MnPS3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 55, 4456–4463 (1986).

Kikkawa, T. et al. Critical suppression of spin Seebeck effect by magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064413 (2015).

Weiler, M. et al. Experimental test of the spin mixing interface conductivity concept. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 176601 (2013).

Heinrich, B. et al. Spin pumping at the magnetic insulator (YIG)/normal metal (Au) interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 066604 (2011).

Tserkovnyak, Y., Brataas, A. & Bauer, G. E. Enhanced gilbert damping in thin ferromagnetic films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 117601 (2002).

Rezende, S. M., Rodriguez-Suarez, R. L. & Azevedo, A. Theory of the spin Seebeck effect in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 93, 014425 (2016).

Jaworski, C. M. et al. Observation of the spin-Seebeck effect in a ferromagnetic semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 9, 898–903 (2010).

Uchida, K. et al. Observation of the spin Seebeck effect. Nature 455, 778–781 (2008).

Xiao, J. et al. Theory of magnon-driven spin Seebeck effect. Phys. Rev. B 81, 214418 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This project has been supported by the National Basic Research Program of China 2019YFA0308402, 2019YFA0308401, 2018YFA0305604, 2015CB921102, the National Natural Science Foundation of China 11934001, 11774010, 11921005, Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation JQ20002, the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences XDB28000000, National Research Foundation Singapore program NRF-CRP21-2018-0007, NRF-CRP22-2019-0007 and Singapore Ministry of Education via AcRF Tier 3 Program ‘Geometrical Quantum Materials’ MOE2018-T3-1-002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-H.C. conceived and coordinated the experiment; G.C. and S.Q. fabricated the devices and performed most of the measurement; S.Y. aided in transport measurement; Y.Z. aided in device fabrication and AFM measurement; M.L., J.L., J.X., X.C., and R.S. provided theoretical analysis; J.L. and R.S. performed the analysis of spin Seebeck coefficient; K.C. performed fitting to various possible mechanisms; S.Q., G.C., and D.C. performed simulations according to J.L. and R.S.’s analysis; P.Y. and Z.L. have grown high-quality MnPS3 bulk crystals; J.-H.C. wrote the manuscript and all authors commented and modified the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, G., Qi, S., Liu, J. et al. Electrically switchable van der Waals magnon valves. Nat Commun 12, 6279 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26523-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26523-1

This article is cited by

-

Electrical detection of spin pumping in van der Waals ferromagnetic Cr2Ge2Te6 with low magnetic damping

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Giant electrically tunable magnon transport anisotropy in a van der Waals antiferromagnetic insulator

Nature Communications (2023)

-

2D materials for intelligent devices

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.