Abstract

Alloying is a powerful tool that can improve the electrocatalytic performance and viability of diverse electrochemical renewable energy technologies. Herein, we enhance the activity of Pd-based electrocatalysts via Ag-Pd alloying while simultaneously lowering precious metal content in a broad-range compositional study focusing on highly comparable Ag-Pd thin films synthesized systematically via electron-beam physical vapor co-deposition. Cyclic voltammetry in 0.1 M KOH shows enhancements across a wide range of alloys; even slight alloying with Ag (e.g. Ag0.1Pd0.9) leads to intrinsic activity enhancements up to 5-fold at 0.9 V vs. RHE compared to pure Pd. Based on density functional theory and x-ray absorption, we hypothesize that these enhancements arise mainly from ligand effects that optimize adsorbate–metal binding energies with enhanced Ag-Pd hybridization. This work shows the versatility of coupled experimental-theoretical methods in designing materials with specific and tunable properties and aids the development of highly active electrocatalysts with decreased precious-metal content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large-scale deployment of fuel cells (FCs) and batteries could help lower anthropogenic CO2 emissions and create a more energy efficient society1,2. Hydrogen FCs (H2 FCs) are particularly interesting because H2 is an abundant commodity already produced at a large scale as an industrial chemical feedstock (~60 Mt y−1)2. Furthermore, H2 FCs can reduce up to ~50% of net CO2 emissions (relative to fossil fuel derived power) if hydrogen is produced by traditional methane reforming, and up to ~90% if hydrogen is produced by electrolysis with renewable electricity1. H2 FC vehicles are attractive for both light-duty and heavy-duty transportation as they can be refueled in minutes and provide sufficient energy density to be viable for a broad range of transportation modes including automobiles, trucks, buses, airplanes, and boats3. The large overpotential required for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) leads to low energy efficiency and is an important factor limiting the implementation of several electrochemical renewable energy technologies such as H2 FCs, direct methanol FCs, and metal-air batteries. Development of catalysts with improved activity, stability, and selectivity for the ORR will be necessary for the large-scale deployment of these technologies.

Based on guidelines from the U.S. Department of Energy, a large portion of H2 FC research and development has focused on lowering catalyst cost by decreasing the Pt content in proton exchange membrane FCs3. This has been done successfully by alloying and microstructuring4,5,6. However, owing to the thermodynamic instability of many first and second row transition metals in acidic conditions during the ORR, further alloy-based routes towards precious-metal elimination at low pH are limited7,8,9. In contrast, anion exchange membrane FCs (AEMFCs) offer a higher pH regime, enabling the stable use of less-expensive materials9. Currently, one of the most active known ORR catalysts in alkaline media is Pd10,11,12,13. Due to its high price, developing bimetallic Pd catalysts with decreased Pd content and/or higher intrinsic activity could make AEMFCs more economical. Ag shows promise as a secondary species because of its relatively low cost, high abundance, base stability, and high 4e− selectivity14,15,16. Furthermore, previous experimental studies have demonstrated enhancement both in Ag-based bimetallics (e.g., Cu-Ag17, Co-Ag18, and Sn-Ag19) and Ag-Pd nano-configurations20,21,22,23, and physics-based modeling24 has predicted enhancement for the ORR based on d-band changes. Understanding the mechanism behind alloy-based enhancement could guide the discovery of structure-activity relationships for more complicated ternary or quaternary systems.

In this work, we use a thin film model system to study the compositional dependence of intrinsic activity for the ORR on Ag-Pd catalysts. Using electrochemical cycling, atomic force microscopy, x-ray diffraction, and x-ray spectroscopies we investigate activity, surface topography, crystal structure & solid miscibility, and composition & electronic structure, respectively. With our highly comparable alloyed catalysts, we demonstrate activities greater than that of pure Pd even after lowering Pd content by half. Using density functional theory together with these experimental results we probe the nature of the active site and rationalize the intrinsic activity trends seen for Ag-Pd electrocatalysts. By lowering the catalyst cost by ~50% via non-precious-metal alloying (Pd is currently ~100 times more expensive than Ag)25, without sacrificing overall performance, this work demonstrates an avenue for making H2 FCs and other electrochemical devices more economical.

Results and discussion

Alloying Ag and Pd as thin films

Ag-Pd alloys have been previously synthesized and are thermodynamically stable and miscible at all compositions20,21,22,23,26,27,28,29,30. Here, we synthesize a series of Ag1-xPdx (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) thin films (~70 nm thick) via electron-beam physical vapor deposition (PVD) and probe the crystal structure, extent of alloying, electronic structure, and topography of the as-prepared thin films with x-ray diffraction (XRD), x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), x-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and atomic force microscopy (AFM). Structurally, grazing incidence XRD (GI-XRD) (Fig. 1a, see full 2θ range for all Ag1-xPdx films in Supplementary Fig. 1a) of the pure Ag and pure Pd thin films shows strong peaks characteristic of a face-centered cubic (fcc) crystal structure with lattice parameters of a = 4.07 Å and a = 3.87 Å, respectively (see lattice data for all Ag1–xPdx films in Supplementary Table 1). Similar to their parent structures, the bimetallic Ag1–xPdx films have peaks corresponding to a fcc structure. Furthermore, at all compositions, the (111) peak ranges between the Ag(111) (38.30°) and Pd(111) (40.35°) peaks (Fig. 1a). The absence of two distinct (111) peaks in the bimetallic thin film diffractograms suggest that Ag and Pd are present as an alloy. Finally, the center of the (111) peak shifts linearly to higher diffraction angles as a function of increasing Pd composition. This linear shift is consistent with a decreasing lattice parameter as Pd is added to the Ag matrix. Using Vegard’s law (Fig. 1b), atomic alloy-compositions are seen to closely follow the nominal thin film composition (defined by the Ag and Pd masses as measured during evaporation), however slight deviations could suggest the presence of minor Pd-richer phases ~50% nominal Pd loading31. In short, XRD analysis highlights that electron-beam PVD produces highly miscible solid solution (alloy) phases of Ag1-xPdx.

a Grazing incidence x-ray diffractograms highlighting the (111) fcc peak as a function of Ag:Pd ratio in Ag1-xPdx films. Ag (38.30°) and Pd (40.35°) (111) peak locations are indicated with dotted lines. (See expanded 2θ range in Supplementary Fig. 1a, and symmetric-geometry diffractograms in Supplementary Fig. 2). b Vegard’s Law analysis of the (111) peak showing Pd content in the alloy versus nominal Pd composition. High resolution c Ag 3d and d Pd 3d XPS spectra as a function of Ag:Pd ratio in Ag1–xPdx films (see survey spectra and XPS compositional analysis in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). e Normalized Pd L3 x-ray absorption near-edge region spectra (Pd L3-edge XANES) for select Ag1–xPdx compositions (x = 1, 0.9, 0.8, 0.5, 0.2), and f FEFF simulated Pd L3-edge XANES for select Ag1-xPdx compositions (x = 1, 0.9, 0.8, 0.5, 0.2). (See full XANES scan in Supplementary Fig. 5). All samples measured on standard glass slides for GI-XRD and on glassy carbon substrates for XPS and XANES. The colors refer to the nominal Pd loading, consistent with the text labels in the figure.

To probe the surface and clarify the role that composition plays in the electronic structure of the Ag1–xPdx alloys, we analyzed high resolution XPS (see survey spectra and XPS compositional analysis in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4) and Pd L3-edge XAS. As seen in Fig. 1c, the binding energy of the Ag 3d peaks shifts negatively as a function of increasing Pd content, with a maximum shift of ~−1.0 eV between Ag and Ag0.1Pd0.9. This negative shift in the Ag 3d doublet, as a function of Pd content, has been seen previously for mixed Ag-Pd systems21,26 and has been attributed to increased charge mixing. Specifically, studies have shown that with increasing Pd content, the electron density in the Ag d-band increases, whereas the electron density in the sp-band decreases21,28,32. The Pd 3d (Fig. 1d) peak positions, however, vary only by a maximum of ~−0.3 eV. This small shift is in qualitative agreement with the majority of previously reported Pd 3d BE shifts in Ag-Pd alloys (mostly negative BE shifts);21,26,28,32 however, owing to instrument energy resolution it is difficult to draw trends as a function of Ag composition.

Although Pd XPS is complicated to interpret, the L3-edge XAS of Pd has been used effectively in the literature to elucidate the charge density within Ag-Pd alloys23,32,33. The small deviations from the single-particle-model for 4d metals makes the use of the L3-edge quantitatively meaningful34. Figure 1e, f (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for the full energy range plot) shows the experimental spectra and FEFF simulations of the Pd L3-edge for several Ag1–xPdx compositions. Looking at the x-ray absorption near-edge spectra (XANES), we see that the normalized white-line (Pd L3-edge peak) intensity decreases with increased Ag loading. This clear decrease in white-line intensity is indicative of a net shift in electron density from Ag to Pd producing a decrease of 4d-holes in Pd32,33,35,36. Moreover, the extended region features in Fig. 1e, f shift to lower energies with increased Ag loading in agreement with an expanding lattice owing to the addition of Ag (see Supplementary Fig. 5)32,33,35,36. The observed trends in the XANES of the Pd L3-edge (Fig. 1e) of Ag-Pd alloy thin films are well reproduced by FEFF simulations (Fig. 1f) of select Ag1–xPdx compositions (x = 1, 0.9, 0.8, 0.5, 0.2). Together, the Ag 3d XPS and Pd L3-edge XAS support a model, similar to that seen in previous Ag-Pd alloys23,32,33, in which the Ag and Pd d-bands become more filled as each metal dilutes the other. According to the d-band theory description of metal-adsorbate interactions, this change in d-band electron density has important catalytic implications that will be described further below.

Finally, AFM (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 2), indicates that the surfaces of the as-prepared Ag1–xPdx thin films are very flat with roughness factors ≤1.02 at all compositions. This highly uniform surface morphology, regardless of composition, suggests that the geometric surface area is approximately equal to the exposed catalyst surface area for all films. Altogether, this in-depth physical characterization of the as-prepared Ag1–xPdx bimetallic thin films indicates that these materials have highly comparable, smooth surfaces. Furthermore, the unique electronic and physical properties as a function of Ag alloying with Pd, particularly the increase in d-band electron density and lattice expansion, motivates the investigation of their intrinsic catalytic activity for the ORR.

Intrinsic ORR activity enhancement with Ag1–xPdx alloying

The development of effective design principles for new materials requires characterizing and understanding the complexities and mechanisms behind activity enhancements. Using cyclic voltammetry (CV), we investigated the ORR activity as a function of alloy composition by cycling (20 mV s−1) various Ag1–xPdx thin films in 0.1 M KOH using a rotating disk electrode (RDE, 1600 rpm) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 7). As seen in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 7, mass transport limited current densities are ~\(- 6\,{\mathrm{mA}}\,{\mathrm{cm}}_{{\mathrm{geo}}}^{ - 2}\), indicating all compositions are selective to the four electron transfer pathway to –OH ( < 0.5% H2O2 (n~3.98) above 0.3 V vs. the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) verified by rotating ring disk electrode and Koutecký–Levich (KL) selectivity measurements on Ag0.1Pd0.9, see Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9, respectively)14,15,16,37. The ORR polarization curves for pure Ag and pure Pd thin films are consistent with those of previous studies showing onset potentials (at \(- 0.1\,{\mathrm{mA}}\,{\mathrm{cm}}_{{\mathrm{geo}}}^{ - 2}\)) ~0.83 V and 0.96 V vs. RHE, respectively14,17,38,39. Furthermore, CV profiles in N2-purged electrolyte for pure Ag and Pd exhibit the redox features expected based on studies of single crystals and polycrystalline electrodes17,21,40,41,42,43,44. The bimetallic Ag1–xPdx thin films demonstrate a combination of these features (Supplementary Fig. 10). Figure 2a shows representative ORR voltammograms (with O2-saturation) for the Ag1-xPdx thin films, where x (%) = 0, 90, and 100. From this voltammetry we see that the highest performing composition, Ag0.1Pd0.9, has a very similar profile to the Pd control, indicating similar selectivity and reaction mechanism. However, this alloy outperforms both parent materials, on average, by a ~20 and ~55 mV lower overpotential, compared to Pd, at \(- 0.1\,{\mathrm{mA}}\,{\mathrm{cm}}_{{\mathrm{geo}}}^{ - 2}\) (onset potential) and \(- 3\,{\mathrm{mA}}\,{\mathrm{cm}}_{{\mathrm{geo}}}^{ - 2}\) (half-wave potential), respectively.

a Select ORR polarization curves for representative Ag, Pd, and Ag0.1Pd0.9 thin films. b Onset potential (bars) (potential at \(- 0.1\,{\mathrm{mA}}\,{\mathrm{cm}}_{{\mathrm{geo}}}^{ - 2}\)), Tafel slope (circles), and c specific activity (kinetic current density at 0.9 V vs. RHE normalized by surface roughness determined by AFM) on an absolute (black circles) and Pd fraction-normalized (color-mapped triangles) bases for all Ag1-xPdx compositions investigated. Measurements were taken at 1600 rpm in O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH, have non-ORR current subtracted (from CVs in N2-purged electrolyte), and are corrected for the uncompensated electrolyte series resistance. All data points are representative of the average value from the cathodic and anodic scan of the third CV cycle and error bars are the standard deviation from measurements with separate samples (see Supplementary Figs. 7, 11, 12 and Supplementary Table 3 for representative ORR CV curves, kinetic current densities at 0.9 and 0.8 V vs. RHE, representative Tafel plots, and tabulated data, respectively). The colors refer to the nominal Pd loading, consistent with the text labels in the figure.

Probing the compositional dependence of this enhancement, we extracted the onset potential (Fig. 2b) and kinetic current density (Fig. 2c, calculated using the KL equation, see Supplementary Equation 1) from the polarization curves of the full Ag1–xPdx compositional range (Supplementary Fig. 7). In Fig. 2b we see that the onset potential for the ORR increases concomitantly with the Pd loading for all bimetallic films, with the most Pd-rich (80–90 at%) compositions onsetting, on average, ~10–20 mV before pure Pd. Moreover, after as much as a 60% decrease in Pd content, the onset potential remains above 0.9 V vs. RHE, indicative of a very high performing catalyst with significantly lowered precious-metal content. To look in depth at performance trends (Fig. 2c), the kinetic current was normalized based on the exposed catalyst surface area determined by AFM topography measurements (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 2) to calculate a specific activity. Importantly, all activity trends remain the same when normalizing by electrochemical double-layer capacitance (potential cycling, Supplementary Fig. 13), geometric electrode area (Supplementary Fig. 11), and exposed catalyst surface area (AFM) (Fig. 2c), indicating that this specific activity trend is representative of the intrinsic activity trend. The specific activity was also normalized by Pd fraction to discern how the intrinsic activity of Pd atoms changes as a function of alloy composition.

As seen in Fig. 2c, there is a clear non-linear enhancement in specific activity at ≥50 at% nominal Pd loadings at 0.9 V vs. RHE. Specifically, films with 50–90 at% Pd have, on average, specific activities (on a Pd content and/or absolute bases) that are greater than both of their parent materials’ activity, with enhancements over pure Pd of 1.7–5.0× on a per Pd basis and 1.5–4.5× on a total specific activity basis. In addition, at 0.8 V vs. RHE (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 13a), a 1.4× specific activity enhancement is also present for Ag0.6Pd0.4 (not seen at 0.9 V vs. RHE due to a lower absolute current density). These activity enhancements suggest the presence of surface sites significantly more active for the ORR compared to pure Pd and Ag. Furthermore, when normalized by Pd content (Fig. 2c, triangles), the activity enhancements beyond the activity of pure Pd increase compared with those seen on a total specific activity basis (Fig. 2c, circles). This could suggest that when Pd is the majority species in the Ag1–xPdx alloyed thin films, Pd active sites are being enhanced.

The Tafel slope analysis of kinetic current densities further supports this Pd site enhancement hypothesis (Fig. 2b, circles). Specifically, there is a striking decrease in Tafel slope, concomitant with the appearance of specific activity enhancements, from ~90–100 mV dec−1 (Ag-like) to ~40–60 mV dec−1 (Pd-like) at Pd compositions of 40 at% or greater. Although the exact mechanistic change(s), leading to the observed differences in Tafel slope are difficult to pinpoint by Tafel analysis alone due to the multi-step nature of the ORR, this suggests intrinsic changes in the structure of the active site, the rate-limiting step, and/or the adsorbates are responsible for the observed enhanced ORR kinetics on the medium-to-high Pd content films45,46. The observed activity enhancements (specific activity at 0.9 V and 0.8 V vs. RHE) are only seen in the electrocatalysts with Tafel slopes similar to that of pure Pd. This could suggest a reaction mechanism similar to that of pure Pd, but in which Pd-based active sites are enhanced by Ag atoms within the lattice via ligand and/or strain effects.

In contrast to the medium-to-high Pd content catalysts, the films with ≤30 at% Pd show performance greater than that of pure Ag, but specific activities less than the linear combination of Ag and Pd activities at 0.8 V (or 0.9 V) vs. RHE. This suggests no overall synergistic effect between Ag and Pd at this low-Pd-content regime. Normalizing by Pd loading suggests that at this high-Ag-content compositional regime Pd atoms are playing an important role and are behaving as they do in their pure metal form (following an approximately linear activity-composition relationship). Moreover, Tafel slope analysis suggests that the reaction mechanism on the low-Pd-loading films is similar to that of pure Ag and supports the hypothesis that Ag is involved in the active site at this compositional regime. Despite no enhancement beyond the linear combination of Ag and Pd activities at this low-Pd-content regime, specific activity, and Tafel slope analyses suggest that both Ag and Pd are playing a role in increasing the overall performance above that of Ag. The composition-dependent role of Ag and Pd in modulating the ORR activity of Ag-Pd alloys will be described in the next section.

Post-reaction characterization of composition, structure, and surface smoothness suggests that the catalyst surface does not significantly change due to ORR testing on the timescale of our electrochemical measurements (see Supplementary Figs. 1, 4, 6, 14, and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2)47. This suggests the ex situ material properties can be meaningfully related to the activity trends, however, in operando physical characterization would be necessary to confirm the exact state of the catalyst surface during reaction. Most notably, the fact that surface smoothness did not change after ORR testing suggests that there was negligible surface restructuring (within AFM detection limits), an effect often associated with roughening48. To probe stability, we performed a chronoamperometry (CA) experiment at 0.8 V vs. RHE, for 2 hrs (Supplementary Fig. 14a), for our best-performing composition, Ag0.1Pd0.9, and observed a decrease in the ORR geometric current density of ~40%. We hypothesize that this decrease in performance, which we find to be recoverable, could be due to carbon uptake from corrosion of the graphite rod counter electrode, as well as possible Pd and/or Ag partial surface oxidation; the latter (oxidation) is in fact one of the main sources of decreased performance in similarly high performing Pt-based ORR catalysts49. ORR CVs pre- and post-CA testing (Supplementary Fig. 14b) support this hypothesis, as 100% of the initial (pre-CA) performance is recovered by cycling the working electrode down to ~−0.2 V vs. RHE to reductively clean off any accumulated carbon and/or surface oxide on the film’s surface. Additionally, using angle resolved (AR)-XPS (Supplementary Fig. 14c), to attain increased surface sensitivity, together with depth profiling (Ar+ sputtering, Supplementary Fig. 14d), we find that the composition of the film did not change significantly as a function of depth after stability testing47,50. Altogether, our stability testing and post-ORR in-depth characterization indicate that there is no irreversible intrinsic material or performance degradation on the timescale of our experiments, supporting the hypothesis that any trends in activity are related to intrinsic differences in material surface electronic structure rather than differences in catalyst morphology or any instabilities. Possible enhancement mechanisms for tuning the oxygen adsorbates binding energies correlated with these enhancements will be discussed in the next section.

Pure Pd catalysts have been noted among the most active materials for the ORR in alkaline media12,13. Here, we have shown that by alloying Ag with Pd we can both decrease the Pd content by 50% without activity loss and enhance the intrinsic activity of Pd five-fold, yielding high performing state-of-the-art ORR electrocatalysts. Supplementary Table 4 compares the specific activity (normalized by a physically representative exposed catalyst surface area) at 0.9 V vs. RHE of our best-performing thin films to representative state-of-the-art electrocatalysts for the ORR in 0.1 M KOH (or similar) using a RDE setup. Notably, our Ag0.1Pd0.9 alloy thin film electrocatalyst is among the most intrinsically active catalysts for the ORR in alkaline media yet reported when normalizing by exposed catalyst surface area. Although out of scope from this work, the high performance of the medium-to-high Pd content Ag-Pd alloys motivates future studies of this ideal catalyst system within FC systems.

Electronic effects on ORR activity from alloying Ag and Pd

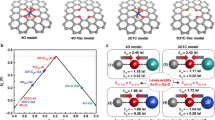

Based on the d-band model, which describes metal-adsorbate orbital hybridization, it is largely understood that there is an optimal *OH/*OOH binding energy for ideal ORR catalysis51,52,53,54. Ag binds oxygen adsorbates too weakly, while Pd binds them too strongly54,55. Hence, the alloying of Ag and Pd might lead to more optimal catalysts, with stronger Ag- or weaker Pd-adsorbate binding24,51,52,53,54,55. Using density functional theory (DFT) we can investigate the theoretical activity for the ORR as a function of Ag-Pd structure and composition. Therefore, a complementary theoretical study was undertaken to gain a fundamental understanding of the nature of the active sites and trends in activity to rationalize the experimental observations, namely the physical and electronic properties and the enhanced ORR activity on Ag-Pd alloys compared with their pure components. First, we identify the composition of the most active sites and then determine the role of strain (tensile or compressive) and ligand (hybridization) effects, both of which can arise from alloying, in modulating the electronic structure within these active sites. We consider a variety of Ag-Pd (111) configurations representative of the synthesized materials (Fig. 3a), as well as all possible active sites, to deconvolute strain from ligand effects. We evaluate activity based on the calculated thermodynamic limiting potential for the ORR (UL)56, which is dependent on the surface binding energies of reacting oxygen adsorbates (Fig. 3b).

a Ag-Pd active site models investigated by DFT for their effect on ORR activity: (i) Ag, (ii) Pdatom–Ag, (iii) Pd, (iv) Ag3Pd1, (v) Ag2Pd2, and (vi) Ag1Pd3. All the considered surfaces are (111) facets. The identified most active sites are: (i) Agtop, (ii) Ag–Pd, (iii) Pd–Pd, (iv) Ag–Pd, (v) Pd–Pd, and (vi) Pd–Pd. b Oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity map showing overpotentials (vs. the computational hydrogen electrode) for various Ag-Pd structures calculated by DFT. η = 1.23 V − UL. (The ORR UL is defined as the highest potential at which all the reaction steps become downhill in energy. Lower η or higher UL indicate improved theoretical ORR activity). See Supplementary Figs. 15–17 and Supplementary Tables 5 and 6 for more details about strain effects, projected density of states, and the tabulated data.

In Ag-Pd alloys, the absolute strain, seen by changes in bond lengths, on each atom (Ag or Pd) changes as a function of the Ag:Pd ratio. This is because, as seen by XRD (Fig. 1a), Pd has a smaller lattice constant than Ag. As a function of this difference in lattice parameter, Pd and Ag atoms will be under increased tensile or compressive strain that strengthens or weakens the adsorption energy of reaction intermediates as a function of Pd content, respectively. Therefore, strain would only lower the activity of pure Ag- or Pd-like active sites (we show a quantitative example of this in Supplementary Fig. 15a). Based on this traditional understanding of strain effects, we would expect no enhancement in activity for the Ag-Pd system. However, there are additional electronic effects to consider for active sites that share electrons locally. To model the activity of Ag-Pd alloys resembling the experimental Ag-Pd thin films, the ORR UL was calculated for the Ag3Pd1(111), Ag2Pd2(111), and Ag1Pd3(111) structures (structures (iv)–(vi) in Fig. 3a). Our calculations suggest that the most active (lowest energy) sites for the Ag2Pd2(111) and Ag1Pd3(111) surfaces are Pd–Pd bridge sites, whereas the active site for Ag3Pd1(111) is the Pd–Ag bridge site. The theoretical activity results for these alloy structures, as well as for Pt(111), Pd(111), and Ag(111) are shown in Fig. 3b. The limiting potentials for Pt(111) and Pd(111) are 0.80 V and 0.79 V, respectively. The limiting potentials for Ag2Pd2(111) and Ag1Pd3(111) are 0.83 V and 0.82 V, respectively, and are slightly higher than for pure Pd(111) indicating enhancement of the Pd–Pd bridge sites in medium-to-high Pd content Ag-Pd alloys. The d-projected density of states analysis (see Supplementary Fig. 16) for the structures in Fig. 3a illustrates that the slightly lower d-band edge relative to the Fermi level observed for Ag1Pd3(111) and Ag2Pd2(111) compared with Pd(111) results in a weaker oxygen adsorption on Pd atoms and consequently an increase in activity. As illustrated by the Pd L3-edge XANES measurements (Fig. 1e) discussed earlier and the calculated Pd effective Bader charge (Supplementary Table 6), this change in Pd d-band arises from the increased filling of Pd 4d-holes upon charge hybridization between Ag and Pd. Therefore, we hypothesize activity enhancements on medium-to-high Pd content electrocatalysts are likely due to ligand effects, specifically optimal charge redistribution between Ag and Pd. Furthermore, the presence of an increased number of active Pd−Pd bridge sites may explain why the experimental activity increases with Pd content despite Ag2Pd2(111) being slightly more theoretically active than Ag1Pd3(111).

Considering the Ag-rich compositional regime, the calculated limiting potential for the ORR on Ag3Pd1(111) (0.72 V) improved relative to Ag(111) but does not reach the enhancement observed in the Ag2Pd2(111) and Ag1Pd3(111) surfaces. To consider strain effects on the predicted mixed-metal active site for structures with <50 at% Pd, we calculated the UL of the Ag−Pd bridge site in a Ag(111) surface with a trapped single Pd atom (Pdatom−Ag) (structure (ii) in Fig. 3a). The calculated UL of Pdatom−Ag is 0.63 V, indicating a slight increase in activity compared to pure Ag(111) with a UL of 0.61 V. For this system, the ORR UL increases with compressive strain (lattice contraction weakens adsorbate binding), indicating that the Pdatom−Ag site lies on the strong binding side of the ORR volcano, as shown in Fig. 3b. With a compressive strain of 5%, Pdatom−Ag (−5%) shows a calculated UL of 0.80 V (see Supplementary Figs. 15b and 17a); tensile strain (lattice expansion), on the other hand, leads to a significant decrease in UL. Ag3Pd1(111), specifically, has an active site similar to Pdatom−Ag(−2%) (UL of 0.66 V), and compressive strain (relative to Ag(111)) arising from the addition of Pd could partly lead to a higher UL, but strain alone does not explain the higher UL for Ag3Pd1(111) compared with Pdatom−Ag(−2%). Therefore, ligand effects are likely also playing a role in increasing the UL of Ag3Pd1(111). Consequently, we conclude that the increased UL for the Ag3Pd1(111) structure is due to the intrinsic electronic interactions between Ag and Pd at such Ag-rich compositions, as well as strain on the Ag–Pd site. However, as suggested by the specific activity of the low-Pd-loading thin films not reaching the linear combination of their parent materials’ activity, the charge hybridization of Ag and Pd, as well as compressive strain, have a suboptimal effect at this compositional regime. Altogether, the DFT calculations on Ag-Pd structures of different composition agree well with the activity enhancement observed in Ag-Pd thin films with medium-to-high Pd-loading, and the lack of synergistic enhancement (but still higher activity than pure Ag) at lower Pd loadings.

Overall, DFT results on mixed-metal structures along with the experimentally observed specific activities for the ORR suggest that the most likely mechanism for activity enhancement is the electronic structure tuning of Pd–Pd active sites induced by the surrounding bonding environment (ligand effects) in medium-to-high Pd content Ag-Pd alloys. For the thin films with low-Pd loading, there is still an increase in limiting potential and onset potential for the ORR relative to pure Ag, but the specific activity is less than the expected linear combination of Ag and Pd activities. Therefore, we can conclude that the Ag-Pd electronic interactions at this low-Pd-loading regime do not enhance ORR activity. Correlating the DFT, XPS, and Pd L3-edge XANES results for the Ag-Pd alloy thin films, the observed activity enhancements for films with ≥40 at% Pd are attributed to electronically enhanced active Pd–Pd sites, which we hypothesize have optimized Pd and Ag d-band filling and center.

In conclusion, Ag1-xPdx thin films, with 0 ≤ x ≤ 1, were synthesized by electron-beam PVD. XRD and XPS measurements indicate that the metals alloyed, and the films were created with the intended nominal composition, which remained approximately constant after electrochemical testing. In alkaline conditions, the ORR activity of the thin films with ≥ 40 at% Pd loading surpassed the linear combination of Ag and Pd activities. In addition to very high activity, Ag0.1Pd0.9 exhibited the most enhanced ORR intrinsic specific activity, on both an exposed catalyst surface area and Pd content bases. Overall enhancements over pure Pd were found down to 50 at% Pd loading, with the intrinsic activity of these films (50–100 at% Pd) among the highest recorded. Based on experimental results and DFT calculations, the observed activity enhancements are mainly attributed to electronically enhanced Pd–Pd active sites leading to improved oxygen binding energies. In this study, we leverage the interplay between alloying, electronic structure, and catalytic activity and provide a platform to tune the local active site environment of materials to make more economical state-of-the-art ORR catalysts.

Methods

Thin film synthesis

Bimetallic thin films were synthesized via electron-beam physical vapor co-deposition (Ag with 99.99% purity and Pd with 99.95% purity targets from Kurt J. Lesker) using a custom made PVD system (Technical Engineering Services) equipped with two electron beams, a thermal source, and a rotating substrate stage. Each source is equipped with an independently calibrated quartz crystal microbalance to allow careful deposition rate and composition control throughout the thin films. Prior to deposition, pre-polished 5 mm diameter glassy carbon disks (HTW Hochtemperatur-Werkstoffe GmbH) were cleaned by sequential sonication for 30 min in soapy water, acetone, ethanol, and isopropanol. Subsequently, they were rinsed in pure Millipore water (R = 18 MΩ cm), and affixed to a 10 cm diameter Si(100) wafer using double-sided Kapton tape. We made 70 nm thick Ag-Pd thin films with individual deposition rates (≤0.11 nm/s individually) set to achieve the desired target bimetallic composition ranging from pure Ag to pure Pd. The electron-beam(s) sweep pattern was an up and down (vertical) sweep motion of an ellipse-shaped beam (elongated in the horizontal axis). We found this sweep pattern to produce more uniform thin films with accurate bulk and near-surface composition. A sticking layer was not used due to adhesion problems, observed in early syntheses, between Ag-Pd thin films and investigated sticking layers (tested 2 nm, 10 nm, 20 nm of Ti or Cr).

Material physical characterization

XPS was performed using a PHI III Versaprobe equipped with Al Kα radiation (1486 eV). Survey spectra were collected using a 224 eV pass energy, and high-resolution spectra were obtained using a 55 eV pass energy. Spectra were collected employing the instrument’s neutralizer and the Ar+ gun in neutralizing mode. The x-ray source was perpendicular to the sample and the sample-to-detector angle was 45° (default). A 200 μm × 200 μm spot was used, and the spot location was set to approximately the center of the samples. The stage height was auto-aligned for each sample-to maximize signal intensity. Compositional quantification of XPS spectra was done using CasaXPS software. Tougaard background corrections were used to calculate the area under the Pd and Ag 3d peaks (manually selected energy range) to subsequently calculate their near-surface atomic composition (with sensitivity factors: SAg, 3d = 18.04 and SPd, 3d = 16.04). XPS spectra were aligned by setting the C 1s peak to 284.8 eV. XAS was performed at beamline 14-3 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in a He-saturated chamber. A small glitch in the data is seen at 3202 eV coming from trace Ar in the He. A four element Vortex detector was used to collect fluorescence from the samples. All XAS data were processed and edge jump normalized using Athena57 software. We obtained 5 μm × 5 μm size non-contact AFM images using a Park Systems XE-70 instrument equipped with a premounted Park Systems NSC15/Al BS tip and calculated topographical information using Gwyddion58 software. XRD measurements were collected on a PANalytical Materials Research diffractometer equipped with a Cu Kα (λ = 0.154 nm) x-ray source. Using a 20 mm beam mask, and a 1/2 mm divergence slit, we collected grazing incidence (\(\omega = 1^\circ\)) measurements and symmetric scans (see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) on Ag-Pd thin films grown on standard glass slides to increase the area of material under illumination and eliminate background interferences from glassy carbon substrates. After electrochemical testing, grazing incidence (\(\omega = 4.4^\circ\)) diffractograms on Ag-Pd thin films grown on glassy carbon substrates were collected employing a 5 mm beam mask, and a 1/8 mm divergence slit. Owing to the low signal to noise ratio in the diffractograms for the samples on glassy carbon substrates, OriginPro was used to fit a Lorentzian distribution profile to these data to quantitatively determine the (111) peak position. Post-electrochemical (removed from electrolyte at the open circuit potential and rinsed with Millipore water (R = 18 MΩ cm)) physical characterization (XRD, XPS, AFM) was performed on all thin films within 1 month of activity testing (stored in air).

Electrochemical/activity characterization

Electrochemical characterization was performed by RDE (1600 rpm) testing using a Pine Research Instruments rotator setup and a Biologic VMP-300 potentiostat. We used a three-electrode cell, and employed a graphite rod counter electrode and a Hg/HgO reference electrode. The reference electrode was calibrated before and after each experiment using an RHE (clean Pt wire in H2-saturated electrolyte). This calibration to 0.00 V vs. RHE was, reproducibly, ~−0.87 V vs. Hg/HgO. The Ag-Pd thin films deposited on glassy carbon disks were mounted in a Teflon RDE tip (Pine Research Instruments) and used as working electrodes. We used 0.1 M KOH as the electrolyte, made from semiconductor grade pellets (Sigma Aldrich) and Millipore water (R = 18 MΩ cm). All polarization measurements were corrected for the uncompensated electrolyte resistance and background non-ORR contributions measured immediately after the polarization measurements. The activity for the ORR was evaluated by CV at 20 mV s−1 from 1 to 0 V vs. RHE. Using thin films <36 hrs old, we performed three CV cycles with continuous oxygen bubbling in O2-saturated electrolyte, followed by two CVs with continuous nitrogen bubbling in N2-saturated electrolyte to correct for non-ORR currents. Cyclic voltammograms, from 0.7 to 0.5 V vs. RHE, in the same N2-saturated electrolyte were collected at 10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 mV s−1 to estimate the double-layer capacitance of the thin films to use as a measure of an electrochemically active surface area. With the same RDE setup (1600 rpm, O2- or N2-sparged 0.1 M KOH), the uncompensated electrolyte resistance was obtained before and after cyclic voltammetry measurements by potential electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

Computational methods

Density functional theory

Periodic spin−polarized DFT calculations were performed using the RPBE exchange correlational functional59, a plane−wave basis set with a cut−off kinetic energy of 500 eV, and the projector-augmented wave method as implemented in the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP version 5.4.4)60,61. Pure Ag and Pd surfaces were modeled as five−layer p(3 × 3) (111) fcc slabs with RPBE optimized lattice constants of 4.219 Å and 3.989 Å, respectively. The Brillouin zone was sampled with a (3 × 3 × 1) Monkhorst−Pack grid62. Ag-Pd systems were modeled as five−layer p(2 × 2) (111) fcc slabs with optimized lattice constants of Ag3Pd1 (4.161 Å), Ag2Pd2 (4.104 Å), and Ag1Pd3 (4.047 Å) and the Brillouin zone was sampled with a Γ-centered (4 × 4 × 1) Monkhorst−Pack grid. In all of the slabs, the bottom three layers were constrained at the bulk positions, whereas the top two layers and the adsorbed species were fully relaxed. The slabs were separated in the perpendicular z direction by 15 Å of vacuum, and a dipole correction was applied. The electronic convergence criterion was 10−5 eV, whereas the force criterion for geometry relaxation was 0.05 eV Å−1 for all forces.

Catalytic activities of the different surface structures were evaluated based on the thermodynamic limiting potential for ORR (UL), versus the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE), defined as the highest potential at which all the reaction steps become exergonic by assuming an association reaction mechanism with *OOH, *O, and *OH as reaction intermediates54,55. The adsorption free energies, ΔGx (for x = *OOH, *O, and *OH) of the adsorbates are calculated as ΔG = ΔE + ΔZPE − TΔS, where ΔE is the difference in electronic energy, ΔZPE is the difference in zero-point energies, and ΔS is the change in entropy of the adsorbed species with respect to the catalyst surface, H2(g), and H2O(g). The (ΔZPE − TΔS) value was taken from an earlier publication54 and subsequently added to all the adsorption calculations. The difference between the equilibrium potential of U = 1.23 V and the limiting potential is referred as the theoretical overpotential (η), i.e., η = 1.23 V − UL. (See Supplementary DFT Methodology Notes for further details about our DFT methods).

FEFF XANES simulations

Pd L3-edge XANES simulations were obtained by FEFF 9.963 using the RPA screening approximation and Hedin-Lundquist exchange-correlation potential for an SCF calculation with a cluster of 7 Å, whereas the size of the cluster for the FMS calculation was 9 Å63. Convergence was checked both for SCF (from 5 Å to 8 Å) and for FMS (from 6 Å to 10 Å) and a total broadening of 3 eV was used. In order to take into account both the crystal structure expansion and the Ag:Pd atomic ratio, the model for the simulation consists of 1 × 1 × 5 supercells built from the experimental fcc structures for Pd (a = 3.8720 Å; ICSD-64918), Ag0.1Pd0.9 (a = 3.911 Å; ICSD-605664), Ag0.2Pd0.8 (a = 3.933 Å; ICSD-197455), Ag0.5Pd0.5 (a = 4.029 Å; ICSD-181301), and Ag0.8Pd0.2 (a = 4.038 Å; ICSD-197458) where the Ag:Pd atomic ratio was adjusted accordingly.

Data availability

All raw data plotted in this work can be accessed on figshare.com through DOI https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13049321. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Dhanushkodi, S. R., Mahinpey, N., Srinivasan, A. & Wilson, M. Life cycle analysis of fuel cell technology. J. Environ. Inform. 11, 36–44 (2008).

Staffell, I. et al. The role of hydrogen and fuel cells in the global energy system. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 463–491 (2019).

Hydrogen Council. Path to hydrogen competitiveness A cost perspective. https://hydrogencouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Path-to-Hydrogen-Competitiveness_Full-Study-1.pdf (2020).

Escudero-Escribano, M. et al. Tuning the activity of Pt alloy electrocatalysts by means of the lanthanide contraction. Science 352, 73–76 (2016).

Wang, D. et al. Structurally ordered intermetallic platinum-cobalt core-shell nanoparticles with enhanced activity and stability as oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. Nat. Mater. 12, 81–87 (2013).

Mizutani, N. & Ishibashi, K. Enhancing PtCo electrode catalyst performance for fuel cell vehicle application. SAE Tech. Paper 2016-01-1187, 1–5 (2016).

Hansen, H. A., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. Surface Pourbaix diagrams and oxygen reduction activity of Pt, Ag and Ni(111) surfaces studied by DFT. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 3722–3730 (2008).

Blizanac, B. B., Ross, P. N. & Markovic, N. M. Oxygen electroreduction on Ag(111): the pH effect. Electrochim. Acta 52, 2264–2271 (2007).

Pourbaix, M. Atlas of Electrochemical Equilibria in Aqueous Solutions. (National Association of Corrosion Engineers, Houston, 1974).

Ge, X. et al. Oxygen reduction in alkaline media: from mechanisms to recent advances of catalysts. ACS Catal. 5, 4643–4667 (2015).

Erikson, H. et al. Oxygen reduction on electrodeposited Pd coatings on glassy carbon. Electrochim. Acta 88, 513–518 (2013).

Yang, Y. et al. Combinatorial studies of palladium-based oxygen reduction electrocatalysts for alkaline fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3980–3988 (2020).

Erikson, H. et al. Electrochemical reduction of oxygen on palladium nanocubes in acid and alkaline solutions. Electrochim. Acta 59, 329–335 (2012).

Blizanac, B. B., Ross, P. N. & Marković, N. M. Oxygen reduction on silver low-index single-crystal surfaces in alkaline solution: rotating ring disk Ag(hkl) studies. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 4735–4741 (2006).

Erikson, H., Sarapuu, A. & Tammeveski, K. Oxygen reduction reaction on silver catalysts in alkaline media: a minireview. ChemElectroChem 6, 73–86 (2019).

Ramaswamy, N. & Mukerjee, S. Fundamental mechanistic understanding of electrocatalysis of oxygen reduction on pt and non-pt surfaces: acid versus alkaline media. Adv. Phys. Chem. 2012, 1–17 (2012).

Higgins, D. et al. Copper silver thin films with metastable miscibility for oxygen reduction electrocatalysis in alkaline electrolytes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 1990–1999 (2018).

Holewinski, A., Idrobo, J.-C. & Linic, S. High-performance Ag–Co alloy catalysts for electrochemical oxygen reduction. Nat. Chem. 6, 828–834 (2014).

Lu, Y., Zhang, N., An, L., Li, X. & Xia, D. Synthesis of high dispersed intermetallic Ag4Sn/C and its enhanced oxygen reduction reaction activity. J. Power Sources 240, 606–611 (2013).

Sekol, R. C. et al. Silver palladium core–shell electrocatalyst supported on MWNTs for ORR in alkaline media. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 138–139, 285–293 (2013).

Slanac, D. A., Hardin, W. G., Johnston, K. P. & Stevenson, K. J. Atomic ensemble and electronic effects in Ag-Rich AgPd nanoalloy catalysts for oxygen reduction in alkaline media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9812–9819 (2012).

Luo, W.-B., Gao, X.-W., Chou, S.-L., Wang, J.-Z. & Liu, H.-K. Porous AgPd–Pd composite nanotubes as highly efficient electrocatalysts for lithium–oxygen batteries. Adv. Mater. 27, 6862–6869 (2015).

Betancourt, L. E. et al. Enhancing ORR performance of bimetallic PdAg electrocatalysts by designing interactions between Pd and Ag. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 2342–2349 (2020).

Greiner, M. T. et al. Free-atom-like d states in single-atom alloy catalysts. Nat. Chem. 10, 1008 (2018).

APMEX. Live USD Palladium Price Charts & Historical Data. https://www.apmex.com/palladium-price.

Ma, Y., Bansmann, J., Diemant, T. & Behm, R. J. Formation, stability and CO adsorption properties of PdAg/Pd(1 1 1) surface alloys. Surf. Sci. 603, 1046–1054 (2009).

Karakaya, I. & Thompson, W. T. The Ag−Pd (Silver-Palladium) system. Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr. 9, 237–243 (1988).

Xing, X.-L. et al. High performance Ag rich Pd-Ag bimetallic electrocatalyst for ethylene glycol oxidation in alkaline media. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165, J3259–J3265 (2018).

Oliveira, M. C., Rego, R., Fernandes, L. S. & Tavares, P. B. Evaluation of the catalytic activity of Pd-Ag alloys on ethanol oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions in alkaline medium. J. Power Sources 196, 6092–6098 (2011).

Morioka, S. & Hasebe, M. Thermodynamic constraints to describe Gibbs energies for binary alloys. J. Phase Equilibria 20, 244–257 (1999).

Denton, A. R. & Ashcroft, N. W. Vegards law. Phys. Rev. A 43, 3161–3164 (1991).

Coulthard, I. & Sham, T. K. Charge redistribution in Pd-Ag alloys from a local perspective. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 4824–4827 (1996).

Witjens, L. C., Bitter, J. H., Van Dillen, A. J., De Jong, K. P. & De Groot, F. M. F. Pd L3 edge XANES investigation of the electronic and geometric structure of Pd/Ag-H membranes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 3903–3906 (2004).

De Groot, F. M. F. et al. Differences between L3 and L2 x-ray absorption spectra of transition metal compounds. J. Chem. Phys. 101, 6570–6576 (1994).

Stöhr, J. Nexafs Spectroscopy. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin/Heidelberg, 1992).

Lu, Z. W., Wei, S. H. & Zunger, A. Electronic structure of random Ag0.5Pd0.5 and Ag0.5Au0.5 alloys. Phys. Rev. B 44, 10470–10484 (1991).

Marković, N. M., Schmidt, T. J., Stamenković, V. & Ross, P. N. Oxygen reduction reaction on Pt and Pt bmetallic surfaces: a selective review. Fuel Cells 1, 105–116 (2001).

Li, B. & Prakash, J. Oxygen reduction reaction on carbon supported Palladium–Nickel alloys in alkaline media. Electrochem. Commun. 11, 1162–1165 (2009).

Jukk, K., Alexeyeva, N., Johans, C., Kontturi, K. & Tammeveski, K. Oxygen reduction on Pd nanoparticle/multi-walled carbon nanotube composites. J. Electroanal. Chem. 666, 67–75 (2012).

Grdeń, M., Łukaszewski, M., Jerkiewicz, G. & Czerwiński, A. Electrochemical behaviour of palladium electrode: oxidation, electrodissolution and ionic adsorption. Electrochim. Acta 53, 7583–7598 (2008).

Diculescu, V. C., Chiorcea-Paquim, A. M., Corduneanu, O. & Oliveira-Brett, A. M. Palladium nanoparticles and nanowires deposited electrochemically: AFM and electrochemical characterization. J. Solid State Electrochem. 11, 887–898 (2007).

Jovic, B. M., Jovic, V. D. & Stafford, G. R. Cyclic voltammetry on Ag(111) and Ag(100) faces in sodium hydroxide solutions. Electrochem. Commun. 1, 247–251 (1999).

Horswell, S. L. et al. A comparative study of hydroxide adsorption on the (111), (110), and (100) faces of silver with cyclic voltammetry, ex situ electron diffraction, and in situ second harmonic generation. Langmuir 20, 10970–10981 (2004).

Savinova, E. R. et al. Structure and dynamics of the interface between a Ag single crystal electrode and an aqueous electrolyte. Faraday Discuss. 121, 181–198 (2002).

Shinagawa, T., Garcia-Esparza, A. T. & Takanabe, K. Insight on Tafel slopes from a microkinetic analysis of aqueous electrocatalysis for energy conversion. Sci. Rep. 5, 13801 (2015).

Mefford, J. T., Zhao, Z., Bajdich, M. & Chueh, W. C. Interpreting Tafel behavior of consecutive electrochemical reactions through combined thermodynamic and steady state microkinetic approaches. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 622–634 (2020).

Tougaard, S. & Jansson, C. Comparison of validity and consistency of methods for quantitative XPS peak analysis. Surf. Interface Anal. 20, 1013–1046 (1993).

Van Spronsen, M. A. et al. Dynamics of Surface Alloys: Rearrangement of Pd/Ag(111) Induced by CO and O2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 8312–8323 (2019).

Hitotsuyanagi, A., Nakamura, M. & Hoshi, N. Structural effects on the activity for the oxygen reduction reaction on n(1 1 1)-(1 0 0) series of Pt: Correlation with the oxide film formation. Electrochim. Acta 82, 512–516 (2012).

Shinotsuka, H., Tanuma, S., Powell, C. J. & Penn, D. R. Calculations of electron inelastic mean free paths. X. Data for 41 elemental solids over the 50 eV to 200 keV range with the relativistic full Penn algorithm. Surf. Interface Anal. 47, 871–888 (2015).

Hammer, B. & Nørskov, J. K. Theoretical surface science and catalysis—calculations and concepts. Adv. Catal. 45, 71–129 (2000).

Pettersson, L. G. M. & Nilsson, A. A molecular perspective on the d-band model: synergy between experiment and theory. Top. Catal. 57, 2–13 (2014).

Nørskov, J. K., Abild-Pedersen, F., Studt, F. & Bligaard, T. Density functional theory in surface chemistry and catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 937–943 (2011).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Kulkarni, A., Siahrostami, S., Patel, A. & Nørskov, J. K. Understanding catalytic activity trends in the oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Rev. 118, 2302–2312 (2018).

Viswanathan, V., Hansen, H. A., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. Universality in oxygen reduction electrocatalysis on metal surfaces. ACS Catal. 2, 1654–1660 (2012).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Nečas, D. & Klapetek, P. Gwyddion: an open-source software for SPM data analysis. Open Phys. 10, 181–188 (2012).

Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 59, 7413–7421 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculation using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Rehr, J. J., Kas, J. J., Vila, F. D., Prange, M. P. & Jorissen, K. Parameter-free calculations of X-ray spectra with FEFF9. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 5503–5513 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Toyota Research Institute. Some of the research efforts involving thin film synthesis and XAS characterization were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division, Catalysis Science Program to the SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis. Part of this work was performed at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities (SNSF), supported by the National Science Foundation under Award ECCS-1542152. We thank SNSF Manger of the Surface Analysis Laboratory, Juliet Jamtgaard, for her valuable assistance in setting up XPS experiments and interpreting the corresponding results. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Science, under Contract DE-AC02-76SF00515. We thank SSRL Scientists Erik Nelson and Matthew Latimer for their assistance in setting up and operating beamline 14-3. J.A.Z.Z. gratefully acknowledges support of the Gates Millennium Graduate Fellowship/Scholarship and the Stanford’s Office of VPGE EDGE Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization by J.A.Z.Z., M.B.S., and T.F.J.; experimental methodology by J.A.Z.Z. and A.L.T. (XAS); computational methodology by G.T.K.K.G. (DFT) and A.G. (FEFF); data analysis by J.A.Z.Z., M.B.S., G.T.K.K.G., A.G., A.T.L., M.E.K., C.H., J.K.N., and T.F.J.; writing—original draft by J.A.Z.Z., M.B.S., and G.T.K.K.G.; writing—review & editing by J.A.Z.Z., M.B.S., G.T.K.K.G., A.G., A.T.L., M.E.K., C.H., J.K.N., and T.F.J.; funding acquisition by J.K.N. and T.F.J.; supervision by M.B.S., J.K.N., and T.F.J.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zamora Zeledón, J.A., Stevens, M.B., Gunasooriya, G.T.K.K. et al. Tuning the electronic structure of Ag-Pd alloys to enhance performance for alkaline oxygen reduction. Nat Commun 12, 620 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-20923-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-20923-z

This article is cited by

-

Gas-balancing adsorption strategy towards noble-metal-based nanowire electrocatalysts

Nature Catalysis (2024)

-

High-performance ionomerless cathode anion-exchange membrane fuel cells with ultra-low-loading Ag–Pd alloy electrocatalysts

Nature Energy (2023)

-

Enhanced Performance of Bimetallic Pd-based Electrocatalysts for Formic Acid Oxidation

Topics in Catalysis (2023)

-

Oxygen Reduction Reaction Studies on Pd Coatings Prepared by Galvanic Exchange of Silver, Nickel and Copper

Electrocatalysis (2023)

-

Acid anion electrolyte effects on platinum for oxygen and hydrogen electrocatalysis

Communications Chemistry (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.