Abstract

Magnetic monopoles have been proposed as emergent quasiparticles in pyrochlore spin ice compounds. However, unlike semiconductors and two-dimensional electron gases where the charge degree of freedom can be actively controlled by chemical doping, interface modulation, and electrostatic gating, there is as of yet no analogue of these effects for emergent magnetic monopoles. To date, all experimental investigations have been limited to large ensembles comprised of equal numbers of monopoles and antimonopoles in bulk crystals. To address these issues, we propose the formation of a two-dimensional magnetic monopole gas (2DMG) with a net magnetic charge, confined at the interface between a spin ice and an isostructural antiferromagnetic pyrochlore iridate and whose monopole density can be controlled by an external field. Our proposal is based on Monte Carlo simulations of the thermodynamic and transport properties. This proposed 2DMG should enable experiments and devices which can be performed on magnetic monopoles, akin to two-dimensional electron gases in semiconductor heterostructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Similar to electrons in a metal, monopoles in spin ice compounds1,2 are believed to be unconfined, interact via a magnetic analogue of Coulomb’s law3, and form magnetic currents in magnetic fields4. While exotic phases of matter such as fractional quantum Hall states5 or Wigner crystals6 can be realized in electronic systems, a natural question is whether magnetic monopoles can also exhibit rich behaviors if their charge and dimensionality can be controlled in a likewise fashion to those of electrons. However, to the best of our knowledge, all the current experiments have been restricted to bulk spin ice systems with equally populated monopoles and antimonopoles4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Here we propose such a platform, a heterointerface between a spin ice (R2Ti2O7) (R = Ho, Dy) and an antiferromagnet (R2Ir2O7) in the pyrochlore family. At the boundary, the exchange field between the iridate and the spin ice has a non-zero flux flowing toward/away from the spin ice, resulting in a charged 2DMG in the adjacent layers of the spin ice. Such boundary conditions are reminiscent of the polar discontinuity at the interface between LaAlO3 and SrTiO3 which hosts a two-dimensional electron gas14,15, and inspired by recent theoretical proposals suggesting the surface crystallization of magnetic monopole and antimonopoles at the material/vacuum interface of spin ice thin films16,17. Such a heterostructure represents an example of a magnetically charged monopole system, providing a unique opportunity to investigate their properties. In the following, we begin by describing the proposed heterostructure where such a 2DMG can be formed. We then investigate its transport and thermodynamics properties, and demonstrate that its properties can be modified by an external magnetic field. Finally, we demonstrate that the 2DMG remains robust even when including longer-ranged dipolar interactions.

Results

Spin structures of R2Ti2O7/R2Ir2O7 heterostructures

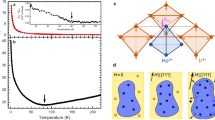

Figure 1a,b shows the crystal and spin structures of spin ice R2Ti2O7 and antiferromagnetic R2Ir2O7. In the spin ice, R3+ has Ising moments on the order of ~10 μB, and obey the “2-in-2-out” ice rules below ~1K. Spin-flip excitations generate tetrahedral sites with “3-in-1-out/3-out-1-in”, which have been described as quasiparticles akin to magnetic monopoles. In the iridate, the Ir4+ forms another tetrahedral network, with an antiferromagnetic “all-in-all-out” (AIAO) order at TN ~ 130K. The R3+ moments in the iridate experience an additional d–f exchange interaction between R3+ and Ir4+ moments. Depending on their relative strength to the nearest neighbor interaction Jdf /Jeff, R3+ moments exhibit an AIAO ordering for Jdf /Jeff > 1, a 3-in-1-out fragmentation configuration for 1/3 < Jdf /Jeff < 1, and remain 2-in-2-out for Jdf /Jeff < 1/318. For simplicity, we first consider the case with AIAO ordering of R3+ moments. The typical ordering temperature of R3+ moments is a few Kelvins, significantly smaller than ordering temperature of Ir4+ moments at ~130K19. As a result, the only moments of interest are the R3+, while Ir4+ moments are treated as a static antiferromagnetic background. In Fig. 1c we illustrate the crystal and spin structure near a R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7 (001) interface. Due to the incomplete coordination of Ir4+ nearest neighbors, the exchange fields experienced by the interfacial R3+ moments in the R2Ir2O7 and R2Ti2O7 layers are 2/3 and 1/3, respectively, of the strength of those in a bulk R2Ir2O7. When the exchange field is sufficiently strong (i.e., Jdf > 2 Jeff), the interface tetrahedra (the topmost red layer) will adopt an AI/AO configuration, forcing the spin ice to adopt a fully polarized state to avoid the formation of monopoles.

a, b Illustrations of lattice and spin structures of a spin ice pyrochlore R2Ti2O7 and an antiferromagnetic pyrochlore R2Ir2O7 respectively, where the nearest neighbor interaction between R3+ moments Jeff and the d–f interaction between a R3+ moment and an Ir4+ moment Jdf are shown. The arrows represent the local moments. The tetrahedral sites with magnetic charge Q = 0 are in gray, Q = qm in green, Q = −qm in yellow, Q = 2qm in blue, and Q = −2qm in red. c Illustration of lattice and spin structure of an R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7 interface with Jdf > 2 Jeff, where the spin ice layer are forced to adopt a fully polarized state. The complete/truncated Ir4+ hexagons are highlighted in green and the complete/reduced local exchange fields experienced by the R3+ moments are materialized by green arrows.

On the other hand, when the spin ice layer is sandwiched in between two iridate slabs, and polarization directions from both interfaces are opposing, as illustrated in Fig. 2a, the boundary condition forbids the ice rule to be satisfied for every spin ice tetrahedral site. As a result, 3-in-1-out monopole defects with a sheet density of 4 unit cells (u.c.)−2 must necessarily exist inside the spin ice.

a a 2D illustration of a static snapshot of a 2DMG in a spin ice R2Ti2O7 slab sandwiched between two antiferromagnetic R2Ir2O7 slabs with the boundary moments terminated to be pointing toward the R2Ti2O7 slab. The tetrahedral sites with magnetic charge Q = 0 are in gray, Q = qm in green, Q = 2qm in blue, and Q = −2qm in red. b A depth profile of the monopole distribution taken from the average of snapshots, and c an example of the snapshot of monopole distribution from the ground states in the Monte Carlo results of a R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7/R2Ir2O7 sandwich with the nearest neighbor model and a parameter with 6Jdf/Jeff = 14.

Unlike in bulk spin ice, where a gas of monopoles and antimonopoles are generated in equal numbers, these monopole defects possess a macroscopic net charge20. Also, unlike monopoles in bulk spin ice, which are associated with a spin-flip excitation, the emergence of these monopoles is not accompanied by the creation of antimonopoles in the spin ice, nor defects in R2Ir2O7. In practice, a macroscopic sample will possess random domains where AO (AI) terminations on both interfaces lead to positively (negatively) charged monopoles, whereas AO/AI combinations should not lead to monopoles (see Supplementary Note 9). In antiferromagnetic pyrochlores, the AI/AO domain size can be as large as few tens of microns, as observed using X-ray micro diffraction and microwave impedance microscopy techniques21,22, which is sufficiently large such that single domains can be investigated. Moreover, these domains can be trained by cooling down under external fields21,22 or via local exchange fields when the iridate is adjacent to a ferromagnetic material, to achieve larger domain sizes. In Fig. 2a, the monopoles are all positively charged in the present boundary condition with \({q}_{m}=(8/\sqrt{3})\mu /a\) where μ is the R3+ moment and a is the pyrochlore lattice constant3. As it does not cost energy to flip a spin connecting a 3-in-1-out site and a 2-in-2-out site, the monopoles should be mobile and form a 2DMG. We also have shown that the above picture can be generalized to a single R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7 interface, (111)-oriented heterostructures, or even artificial spin ice systems23 (see Supplementary Note 13).

Simulation results of nearest neighbor 2DMGs

To quantitatively explore the physics of this interface, we employ Monte Carlo simulations to investigate the magnetic and thermodynamic properties of the heterostructure including both R2Ti2O7 spin ice24 and R2Ir2O7 antiferromagnetic compounds18. For simplicity, we initially consider only nearest neighbor interactions:

where \({\sigma }_{i},{\tilde{\sigma }}_{\alpha }=\pm\! 1\) are the R3+ and the Ir4+ Ising pseudo-spins pointing toward or away from a tetrahedron, 〈i, j〉 represents summations over nearest neighboring sites, Jeff is the effective nearest neighbor interaction between R3+ moments, and Hloc = 6Jdf is a material-dependent tunable parameter that depends on the d-f exchange interaction between R3+ and Ir4+ moments. In this model, the altered local environment of the interfacial R3+ moments are simply treated by the summation according to the reduced coordination of nearest neighboring Ir4+ moments, as shown in Fig. 1c. In Fig. 2c, we show a snapshot of the ground state monopole distribution in an 8-atomic-layer-thick R2Ti2O7 slab sandwiched between two R2Ir2O7 slabs with (001) orientation for Hloc /Jeff = 14. In the R2Ti2O7 slab, a gas of singly charged monopoles is evident. Averaging over snapshots gives a cross-sectional monopole density profile as shown in Fig. 2b, showing that the monopoles are denser closer to the R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7 interface. Investigations of the thickness dependence of the spin ice slab shows that the 2DMG is confined within 3–4 unit cells of the interface due to entropic considerations (see Supplementary Notes 2 and 5). The integrated sheet density of the entire R2Ti2O7 slab is n2D = 4qmu.c.−2, independent of the R2Ir2O7 or R2Ti2O7 layer thickness, consistent with the origin of the 2DMG arising from the boundary conditions.

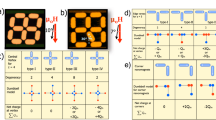

To investigate the transport characteristics of the 2DMG, we apply an oscillating longitudinal magnetic field B0e−iωt (B0 = 0.01T and 1/(2πω) = 20 Monte Carlo steps) and calculate the sheet conductivity σ2D = (BS)−1dM /dt ~ Jm /B of the sandwich structure, as well as a pure spin ice and a pure iridate slab for baseline comparisons, where M is the total magnetization of the system, S is the in-plane area of the heterostructure, and Jm is the magnetic charge current, as shown in Fig. 3a. As expected, neither the bulk iridate or spin ice materials exhibit appreciable conductivity at the lowest temperatures. The peak in the conductivity of the bulk spin ice arises from the combination of paramagnetism above 1K and monopole-antimonopole recombination processes below 1K. For the sandwich structure, the conductivity begins to increase around 1K, and monotonically increases with decreasing temperature. While such behavior is reminiscent of a metal, in sharp contrast to its bulk constituents, we emphasize that this system cannot exhibit a finite DC conductivity in steady state.

a Idealized monopole A.C. sheet conductivity of the sandwich, whose unit is defined as Bohr magneton per squared pyrochlore unit cell per Tesla per Monte Carlo step, taken at the frequency of 1/20 Monte Carlo steps as a function of temperature with Hloc∕Jeff = 14 showing a metallic transport behaviour as well as those for a pure iridate slab and a pure spin ice slab as references showing insulating transport behaviours. b The Hloc∕Jeff-T phase diagrams of the sandwich showing the monopole sheet magnetic charge density n+ and the antimonopole sheet density n−. The above simulations are made with the nearest neighbor model.

In Fig. 3b, we show the total sheet density of monopoles n+ and antimonopoles n− as a phase diagram of temperature and Hloc /Jeff. Above the spin ice freezing temperature of a few Kelvins, the system is paramagnetic and dominated by thermal fluctuations. For 0 < Hloc /Jeff < 12, a singly charged 2DMG always exists within a finite temperature window, due to the non-zero flux of the exchange field that flows toward/away from the spin ice. As the temperature is lowered toward the ground state, the system exhibits different phases for various Hloc /Jeff values. For Hloc /Jeff > 12, a metallic 2DMG persists to the lowest temperatures, which is the case as shown in Fig. 2. For 6 < Hloc /Jeff < 12 and 2 < Hloc /Jeff < 6 regions, where the iridate adopts AIAO and fragmented phases respectively, the boundary tetrahedral layers have pinned, fragmented charges due to the insufficient interfacial exchange fields. As a result, a 2DMG exists at finite temperatures for these Hloc /Jeff values, but is not the ground state. At Hloc /Jeff = 6, the iridate is on the phase boundary between the AIAO and fragmentation phases, and the 2DMG state arises from the resulting spin fluctuations. Nevertheless, a charged 2DMG exists over all values of Hloc /Jeff in the phase diagram, and thus should be experimentally accessible in real material systems.

We have also investigated the 2DMG in R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7/R2Ir2O7 (111) sandwiches with a Kagomé R3+ termination on the iridate layer, as shown in Fig. 4a. In Fig. 4b we plot the Hloc /Jeff-T phase diagram of the sheet density of monopoles and antimonopoles. This phase diagram is qualitatively similar to that of a (001)-oriented heterostructure, but here the 2DMG ground state is even more robust. In the region with 3 < Hloc /Jeff < 6, a 2DMG (which we label as 2DMG-K1) exists with a sheet density of \({n}_{0}^{111}\) (where \({n}_{0}^{111}=4{q}_{m}/\sqrt{3}\)a−2 is a sheet density when 3-in-1out monopoles fully occupy a single tetrahedra layer along the (111) direction), and covers the experimentally determined value of Hloc /Jeff = 4.5 for Ho2Ir2O718. For Hloc /Jeff > 6, the total sheet density increases to \(3{n}_{0}^{111}\), (labeled as 2DMG-K2), where the additional \(2{n}_{0}^{111}\) arises from immobile monopoles pinned to the interfacial layers, as shown in Fig. 4c. We have also calculated the (111) sandwich structure with the triangular R3+ termination, and found that its behavior is qualitatively similar to the Kagomé termination.

a Illustration of the lattice structure of the R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7 (111) interface. b Monopole (antimonopole) sheet density n+(n−) of the sandwich. Two distinct 2DMG phases are observed, as characterized by different monopole densities in the spin ice slab. c Monopole distribution profiles of both 2DMG phases at the ground state. The mobile 2DMG layers are labeled by green bars, whereas the immobile monopole layers are labeled by light green bars. The above simulations are made in R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7/R2Ir2O7 (111) with the nearest neighbor model.

In Fig. 5, we demonstrate that the sheet density of the 2DMG can be controlled by an external, out-of-plane magnetic field. Here, we choose a single interface, because an out-of-plane field will not deplete or accumulate the 2DMG in the sandwich configuration shown in Fig. 2, but rather preferentially move monopoles towards one or the other interface. Although the 2DMG is not the ground state for a single interface, it can be thermally excited at arbitrarily low temperatures which scale inversely with the thickness of the spin ice layer (e.g., ~700 nK for a 1 mm thick layer, the thickness of a typical substrate or bulk crystal). Figure 5a shows the monopole sheet density as a function of magnetic field BG (similar to a gate voltage in a field effect transistor), with positive direction defined as pointing from the iridate to the spin ice. With a negative field, the monopoles are driven away from the interface and pushed into the bulk of the iridate, and the 2DMG can then be fully depleted at a BG of 10 mT, while with a positive field, the monopoles are driven toward the interface, and saturate at a density of 2qmu.c.−2, since the maximum sheet density is determined by the boundary conditions. Figure 5b shows the monopole sheet conductivity σ2D as a function of BG. In negative BG, σ2D decreases toward zero as the 2DMG is depleted, whereas at positive bias σ2D also decreases since the the monopoles are pushed toward the boundary, thereby reducing the number of empty sites into which a monopole can hop.

a Monopole sheet density n2D and b sheet conductivity σ2D as a function of a vertical magnetic gating field BG. We choose to study a positively charged 2DMG with all-out termination on the boundary. The definition of positive BG is shown in the inset of panel a. The Monte Carlo simulation is performed at 0.1 K on an R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7 (001) single interface with the nearest neighbor model and Hloc∕Jeff = 14.

Simulation results of dipolar 2DMGs

Having demonstrated the existence and properties of a 2DMG in the simplest nearest neighbor-only model, we now explore the effects of the long-range dipolar interaction between R3+ − R3+, which should act as an effective Coulomb interaction between monopoles. We find that the existence of the charged 2DMG is robust against dipolar interactions. We now add these additional non-nearest neighboring terms into the Hamiltonian:

where \({(i,j)}^{\prime}\) represents summations over non-nearest neighboring sites, ei is a unit vector along the positive direction of an Ising pseudo-spin σi.

Figure 6a shows the ground state snapshot of the monopole distribution of a trilayer of a spin ice slab (eight atomic layers) sandwiched in between two iridate slabs for Hloc /Jeff = 10, taking into account dipolar interactions. Due to this effective Coulomb repulsion, monopoles are pushed to the boundary layer and form a two-dimensional stripe-like ordering with q = (π /2, π /2), reminiscent of the charge-stripe ordering observed in complex oxides such as cuprates with strong electron correlations25. Upon warming, this ordered state melts and some monopoles overcome their Coulomb repulsion and enter the interior of the spin ice layer, forming a 2DMG similar to the simpler nearest-neighbor-only case illustrated in Fig. 6b. The sheet density of the interacting 2DMG is considerably smaller than that of the non-interacting, nearest-neighbor-only 2DMG, since due to the long-range interactions, many of the monopoles remain confined to the boundary layer. Although quantitative details about the density and distribution are affected by the long-ranged interactions, our calculations nevertheless show that the existence of the 2DMG is indeed robust against Coulomb interactions.

Depth profiles and 3D illustrations of monopole distributions of a R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7/R2Ir2O7 sandwich with dipolar interactions turned on. a In the ground state, the monopoles form a 2D stripe ordering at the boundary layers. b At 0.7 K, the 2D order melts and some monopoles enter the interior of the spin ice layers. The sheet density of escaped monopoles is shown. The Monte Carlo simulation is performed in a R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7/R2Ir2O7 (001) sandwich and Hloc∕Jeff = 10.

Discussion

These proposed heterostructures can be realized using modern thin film growth techniques such as molecular beam epitaxy or pulsed laser deposition, owing to the stable +4 valence of Ir and Ti, as demonstrated by the recent successful growth of the spin ice and the iridate thin films26,27,28,29. While the lattice mismatch between bulk spin ice and iridate compounds is comparatively small (1%), even a modest epitaxial strain can lift frustration in the spin ice layer26. To avoid this complication, the heterostructure can be synthesized on a substrate which is directly lattice matched to the spin ice material (e.g. a pyrochlore titanate single crystal), since the antiferromagnetism in the iridate layer is likely more robust against small anisotropies. Finally, the magnetization signal from the motion of the 2DMG should, in principle, be detectable by conventional superconducting quantum interference device magnetometers (10−8 emu sensitivity), since the sheet density of monopoles is estimated to be ~4 × 1014 cm−2 or ~7 × 1012 cm−2 for the nearest neighbor only and dipolar calculations, respectively. Assuming a detection area on the order of a few square millimeters, the hopping of the dipolar 2DMG should yield a changing magnetization signal of ~10−7 emu.

The proposed 2DMG should enable possibilities in the study of emergent magnetic monopoles not possible in bulk materials. Its active magnetic charge degree of freedom should allow for the isolation of monopoles or antimonopoles30, while the lowered dimensionality of the system should facilitate the fabrication of transistor-like geometries where the density of monopoles can be actively controlled. This will allow one to address outstanding questions including whether emergent monopoles carry an electric dipole akin to the spin of an electron30, whether they experience Lorentz force in electric fields and exhibit an analogous Hall effect, and their energy-momentum dispersion relationship.

Methods

Monte Carlo simulations

The Monte Carlo simulations have been performed based on the Ising model of the pyrochlores, with σi = ±1 being the Ising pseudo-spin representation of a R3+ moment pointing toward or away from a given tetrahedron. The value of σi is then simulated according to the spin model and the Monte Carlo method with the standard Metropolis algorithm18,24. For the nearest neighbor-only model, a single spin-flip algorithm was combined with a worm-loop algorithm to prevent the system from being trapped in a local minimum at low temperatures. For the long-ranged interactions, a parallel algorithm was also used. The worm-loop algorithm developed for the pyrochlore heterostructures was based on the loop algorithm used in previous works18,24,31,32 (see Supplementary Note 4). For R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7/R2Ir2O7 heterostructures, the simulations were performed on 16 × I2 × K lattice sites with periodic boundary conditions, where I = 4 and K = 12. For R2Ir2O7/R2Ti2O7 heterostructures, the simulations were performed on 16 × I2 × K lattice sites with periodic boundary conditions along in-plane directions, where I = 4 and K = 30. We have increased the in-plane model size from I = 4 to I = 10 and did not see difference in 2DMG properties. We have also varied the spin ice slab thickness, and discovered the natural confinement depth of the 2DMG. In total, 106 hybrid Monte Carlo steps were used for the thermalization, including at least 107 single spin-flip steps.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable requests.

Code availability

All relevant codes are available from the authors upon reasonable requests.

References

Ramirez, A. P., Hayashi, A., Cava, R. J., Siddharthan, R. & Shastry, B. S. Zero-point entropy in ‘spin ice’. Nature 399, 333–335 (1999).

Bramwell, S. T. & Gingras, M. J. P. Spin ice state in frustrated magnetic pyrochlore materials. Science 294, 1495–1501 (2001).

Castelnovo, C., Moessner, R. & Sondhi, S. L. Magnetic monopoles in spin ice. Nature 451, 42–45 (2008).

Bramwell, S. T. et al. Measurement of the charge and current of magnetic monopoles in spin ice. Nature 461, 956–959 (2009).

Tsui, D. C., Stormer, H. L. & Gossard, A. C. Two-dimensional magnetotransport in the extreme quantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 1559–1562 (1982).

Goldman, V. J., Santos, M., Shayegan, M. & Cunningham, J. E. Evidence for two-dimentional quantum wigner crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 2189–2192 (1990).

Fennell, T., Bramwell, S. T., McMorrow, D. F., Manuel, P. & Wildes, A. R. Pinch points and kasteleyn transitions in kagome ice. Nat. Phys. 3, 566 (2007).

Morris, D. J. P. et al. Dirac strings and magnetic monopoles in the spin ice Dy2Ti2O7. Science 326, 411–414 (2009).

Bovo, L., Bloxsom, J. A., Prabhakaran, D., Aeppli, G. & Bramwell, S. T. Brownian motion and quantum dynamics of magnetic monopoles in spin ice. Nat. Commun. 4, 1535 (2013).

Grams, C. P., Valldor, M., Garst, M. & Hemberger, J. Critical speeding-up in the magnetoelectric response of spin-ice near its monopole liquid-gas transition. Nat. Commun. 5, 4853 (2014).

Pan, L. et al. Low-energy electrodynamics of novel spin excitations in the quantum spin ice Yb2Ti2O7. Nat. Commun. 5, 4970 (2014).

Pan, L., Laurita, N. J., Ross, K. A., Gaulin, B. D. & Armitage, N. P. A measure of monopole inertia in the quantum spin ice Yb2Ti2O7. Nat. Phys. 12, 361 (2015).

Dusad, R. et al. Magnetic monopole noise. Nature 571, 234–239 (2019).

Ohtomo, A. & Hwang, H. Y. A high-mobility electron gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface. Nature 427, 423–426 (2004).

Nakagawa, N., Hwang, H. Y. & Muller, D. A. Why some interfaces cannot be sharp. Nat. Mater. 5, 204–209 (2006).

Jaubert, L. D. C., Lin, T., Opel, T. S., Holdsworth, P. C. W. & Gingras, M. J. P. Spin ice thin film: Surface ordering, emergent square ice, and strain effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 207206 (2017).

Lantagne-Hurtubise, E., Rau, J. G. & Gingras, M. J. P. Spin-ice thin films: Large-n theory and monte carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021053 (2018).

Lefrançois, E. et al. Fragmentation in spin ice from magnetic charge injection. Nat. Commun. 8, 209 (2017).

Matsuhira, K., Wakeshima, M., Hinatsu, Y. & Takagi, S. Metal-insulator transitions in pyrochlore oxides Ln2Ir2O7. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 80, 094701 (2011).

Jackson, J. D. Classical Electrodymanics (Wiley, London, New York and Sydney, 1962).

Tardif, S. et al. All-in-all-out magnetic domains: X-ray diffraction imaging and magnetic field control. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 147205 (2015).

Ma, E. Y. et al. Mobile metallic domain walls in an all-in-all-out magnetic insulator. Science 350, 538–541 (2015).

Wang, R. F. et al. Artificial ‘spin ice’ in a geometrically frustrated lattice of nanoscale ferromagnetic islands. Nature 439, 303–306 (2006).

denHertog, B. C. & Gingras, M. J. P. Dipolar interactions and origin of spin ice in ising pyrochlore magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3430–3433 (2000).

Pelc, D., Vuckovic, M., Grafe, H.-J., Baek, S.-H. & Pozek, M. Unconventional charge order in a co-doped high-tc superconductor. Nat. Commun. 7, 12775 (2016).

Bovo, L. et al. Restoration of the third law in spin ice thin films. Nat. Commun. 5, 3439 (2014).

Bovo, L., Rouleau, C. M., Prabhakaran, D. & Bramwell, S. T. Phase transitions in few-monolayer spin ice films. Nat. Commun. 10, 1219 (2019).

Gallagher, J. C. et al. Epitaxial growth of iridate pyrochlore Nb2Ir2O7 films. Sci. Rep. 6, 22282 (2016).

Ohtsuki, T. et al. Strain-induced spontaneous hall effect in an epitaxial thin film of a luttinger semimetal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 8803–8808 (2019).

Khomskii, D. I. Electric dipoles on magnetic monopoles in spin ice. Nat. Commun. 3, 904 (2012).

Melko, R. G., denHertog, B. C. & Gingras, M. J. P. Long-range order at low temperatures in dipolar spin ice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 067203 (2001).

Melko, R. G. & Gingras, M. J. P. Monte carlo studies of the dipolar spin ice model. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 16, R1277–R1319 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank D.G. Schlom, K. Nowack, Y. Li, and S. Zhang for helpful discussions. This work was supported through the National Science Foundation [Platform for the Accelerated Realization, Analysis, and Discovery of Interface Materials (PARADIM)] under Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-1539918, NSF DMR-1709255, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research Grant No. FA9550-15-1-0474. This research was also funded by the W.M. Keck Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was designed by L.M. and supervised by K.M.S. The Monte Carlo simulations are performed by L.M., Y.L. and A.B.M. with, consultation from M.J.L. The manuscript was written by L.M. and K.M.S. with feedback from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors delcare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miao, L., Lee, Y., Mei, A.B. et al. Two-dimensional magnetic monopole gas in an oxide heterostructure. Nat Commun 11, 1341 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15213-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15213-z

This article is cited by

-

Anomalous magnetoresistance by breaking ice rule in Bi2Ir2O7/Dy2Ti2O7 heterostructure

Nature Communications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.