Abstract

Recent recession of the Larsen Ice Shelf C has revealed microbial alterations of illite in marine sediments, a process typically thought to occur during low-grade metamorphism. In situ breakdown of illite provides a previously-unobserved pathway for the release of dissolved Fe2+ to porewaters, thus enhancing clay-rich Antarctic sub-ice shelf sediments as an important source of Fe to Fe-limited surface Southern Ocean waters during ice shelf retreat after the Last Glacial Maximum. When sediments are underneath the ice shelf, Fe2+ from microbial reductive dissolution of illite/Fe-oxides may be exported to the water column. However, the initiation of an oxygenated, bioturbated sediment under receding ice shelves may oxidize Fe within surface porewaters, decreasing dissolved Fe2+ export to the ocean. Thus, we identify another ice-sheet feedback intimately tied to iron biogeochemistry during climate transitions. Further constraints on the geographical extent of this process will impact our understanding of iron-carbon feedbacks during major deglaciations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The limited availability of iron (Fe) in the surface Southern Ocean, compared to major nutrients such as nitrate and phosphate, leads to underutilization and thus outgassing of upwelled CO2 in some areas of the modern Southern Ocean1,2. Relief of this Fe limitation, and sequestration of carbon into the deep ocean, is thought to enhance the Southern Ocean’s ability to act as a mediator of global climate over millennial to ice-age timescales3,4. However, the source, transport, and fate of Fe in the Southern Ocean has been widely debated, with sources ranging from dust, ice sheets, iceberg-rafted debris (IRD) to sub-ice shelf, and other continental shelf sediments5. With evidence supporting spatially variable contributions of Fe from numerous sources to the Southern Ocean, consideration of the configuration of ice shelves and their dynamics is vital for understanding how changes in Fe supply help to drive carbon uptake in the Southern Ocean.

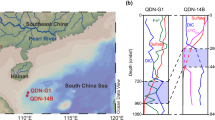

The Antarctic Peninsula, one of the fastest-warming regions on the Earth6, acts as a sentinel for changes in Antarctic ice dynamics. Since the short period of satellite observations, rapid disintegration of ice shelves and retreat of continental glaciers has been observed on the Antarctic Peninsula and linked to potential increases in sea level rise7. Larsen ice shelves A and B (LIS-A and LIS-B) disintegrated catastrophically in 1995 and 2002, respectively, whereas the largest of the peninsular ice shelves, LIS-C, has persisted, decreasing in the size, and thinning through the Holocene to the present8 (Fig. 1). Similar to many other places in Antarctica9, grounding line retreat for LIS-C has been observed to be faster than the average rate since the Last Glacial Maximum9 (LGM) of 25 m/year, particularly between 2010 and 2016.

a Study area (yellow box) along the northern Antarctic Peninsula. b EAP13-GC16B sediment core collected from Larsen ice shelf C (LIS-C) embayment. Ice core drilling site7, James Ross Island is north of Larsen ice shelves A (LIS-A) and B (LIS-B).

Environmental change on the Antarctic Peninsula also significantly impacts the redox conditions of surface sediments during the retreat of ice shelves, driven by the overlying bottom waters changing from relatively stagnant to open-ocean oxygenated conditions10,11. These redox changes in the sediments may cause a variation in clay mineral alteration12,13. Around 50% of the clay minerals of Antarctic sub-ice shelf sediments are composed of illite14, which contains redox-sensitive Fe in its crystal structure, and is thus potentially sensitive to changes in sediment redox conditions. Traditionally, however, alteration of illite crystallinity (IC) has been assumed to require temperature and pressure, and thus be restricted to low-grade metamorphic settings15,16. Recently, although, in situ alteration of illite has been identified beyond such metamorphic settings, and used to reconstruct paleoclimate conditions such as the Holocene monsoonal weathering, for example, Yangtze River17, and Southwest Indian continental shelf18. In these studies, chemical weathering in organic-rich sediments is thought to drive the IC alteration, accelerated by wet and warm monsoonal conditions. However, none of these studies have considered the possibility of microbial alteration of illite at low temperatures. Microbially induced geochemical reactions can modify both mineral structure and chemistry13, properties that are sensitive to redox conditions12, and microbes are present in cold but diverse glacio-marine environments19 associated with ice sheets20, introducing the possibility that microbes may play a role in biogeochemical weathering and mineral alteration, even at very low temperatures21. Whereas a range of iron minerals are known to be sources of dissolved Fe upon breakdown by iron-reducing or -oxidizing bacteria22,23, adding illite to this group, and at low temperatures, provides a potential new broadly distributed mechanism of dissolved Fe2+ to sediment porewaters from the microbial alteration of clay minerals24,25. This process is distinct from reductive Fe production by microbial respiration of Fe hydroxides26.

Here we demonstrate that microbe–illite interactions can be significant at low temperatures and pressures, affecting dissolved Fe2+ release to porewaters and the overlying water column and thus productivity and carbon cycling in the Southern Ocean. As such, we present a broadly applicable alternative pathway for dissolved Fe2+ production in sediment porewaters through microbial alteration of clay minerals, in addition to Fe(III) oxides, the strength of which will change corresponding to the depositional conditions during the expansion and retreat of ice shelves.

Results and discussion

Lithological setting

To address the possibility of IC changes sourcing Fe to the water column beneath an ice shelf, we collected a 2.38-m-long marine sediment core (EAP13-GC16B) on the northwestern part of the LIS-C embayment (Fig. 1) aboard the icebreaker R/V Araon in 2013 (ANA03C Cruise). This core from the continental shelf provides us with information on changes in sedimentary environments during deglaciation, such as the proximity and stability of ice shelves and the influx of meltwater and terrigenous sediments27. The sedimentary sequence unveiled adjacent to LIS-C preserved a depositional record through the Holocene at shallow core depths (<3 m), below the temperatures and pressures of metamorphic modifications28. As such, our core represents an excellent test for the capability of biogeochemical reactions to alter the mineralogical characteristics of the subsurface Antarctic shelf sediments during the Holocene. Core EAP13-GC16B is defined by four distinct lithological units (U1–4) (Fig. 2a), with the upper unit U1 being characterized by sandy clay and IRD, foraminifera and diatoms, U2 and U3 by well-laminated silty clays, and U4 by sandy diamicton with cobbles, with a sharp boundary between U3 and U4 (Fig. 2b). These sedimentary sequences span the transitions from glacial through sub-ice shelf (6000 ± 420, 8000 ± 410, and 11,500 ± 470 cal. years BP at 85, 95, and 192 cm; U2–3) to occasionally open marine conditions (1660 ± 70, and 4140 ± 70 cal. years BP at 0 and 14 cm; U1) since the LGM (Fig. 2c–e), based on calibrated dates derived from application of Ramped PyrOx 14C29. The dark gray sandy diamicton present in U4 is interpreted as being rapidly deposited proximal to the grounding zone of ice shelf during the LGM30, whereas the overlying characteristic laminations of U2–3, for example, yellowish brown sandy mud (21–40 cm) and rhythmic couplets (~6 couplets/cm) of laminated silt and clay (120–180 cm) are typical of sedimentary facies when an ice shelf retreats and undergoes ice-thinning process during the Holocene climate optimum31. Finally, the presence of IRD and foraminifera in the bioturbated sediment of U1 support oxic and seasonally opened marine conditions10. X-ray diffraction (XRD) profiles show that the major mineral compositions for the clay size sediments throughout the core are smectite, chlorite, kaolinite, and illite and lepidocrocite (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Depth profiles of clay minerals throughout the core show that illite is dominant (50–60%) compared with smectite (~10 %), chlorite (~20%), and kaolinite (~15%). There is a clear separation of chlorite (14 Å) and smectite (17.5 Å) for glycolated samples (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

a Sedimentary facies (four distinct lithological units from top (U1) to bottom (U4)) with X-ray core image, b grain-size proportion, c isotopic composition (δ13C and δ15N), d iIllite crystallinity (standard deviations were calculated using three independent sets) and calibrated dates, e holocene temperature history of Antarctic Peninsula modified from Mulvaney et al. 7, and f X-ray diffractograms of clay minerals (S: smectite; I: illite; C: chlorite; K: kaolinite).

Negative values of δ15N within U4 (Fig. 2c) suggest that no organic matter was supplied from the marine environment to these sediments, more typical of a glacial till. In contrast, abrupt increase of δ15N within U3, coupled with consistently lighter values of δ13C through U4 and U3 and a complete lack of diatom frustule or fragments29, suggest a stable sub-ice shelf environment apparently controlled by proximity to the grounding line of LIS32. Similar values of δ13C between U4 and U3 likely reflect the contribution of the suspended particles transported from the grounding line. Higher in the core, the increase in both δ13C and δ15N up to the values observed in U2 and U1 (U1: −25.7‰ and 3.8‰; U2: −25.9‰ and 3.2 ‰; see Supplementary Table 1) is likely to be the result of gradually increasing supply of the marine organic matter from open water column as reflected in grain-size distribution of illite and the presence of diatom frustule fragments in U124.

Evidence for alteration of illite

Alteration of illite minerals can be expressed in terms of IC (°Δ2θ)16. The average values of IC in Core EAP13-GC15B show variation with depth in the core (Fig. 2d, f). Importantly, an abrupt decrease in IC values from ~1.0 (U3) to <0.8 (U2–1) was observed during U2 (at ~4000 BP) (Fig. 2e), suggesting less-altered illite close to the surface. Overall, alteration of the illite between U3 and U1 is also supported by the modification of the illite structure from randomly ordered/diffused Bragg’s reflections in U3 to a discrete ordered pattern in U1 (Fig. 3), and variation in the Fe-oxidation state of the illite particles, with more Fe(III) present at shallower depths (35% in U1 and 17% in U3; Fig. 4a).

Samples with depths of a 0–5 cm (U1), b 60–65 cm (U2), c 120–125 cm (U3), and d 215–220 cm (U4) of the core EAP13-GC16B (dashed lines show the boundary of illite (I) packets). The inset histograms of the grain-size distribution of illite (U4–1) flatten, broaden, and shift to larger size with a high standard deviation. The inset selected area electron diffractions of illite (d001 = 1.0 nm) shows modification of illite structure of randomly ordered/diffused Bragg’s reflections (U3) to discrete ordered pattern (U1).

a Electron energy loss spectroscopy spectra of illite grains for U1 and U3 measuring a chemical shift of Fe L3 edges (~1.2 eV). A calculated integral intensity ratio of Fe L3/L2 (3.24 and 1.89) for illite corresponds to Fe3+/Fetotal of 35 and 17% for U1 and U3, respectively. b Elemental composition typical of illite with 9–14 wt% of Fe contents and 0.41–0.44 of Al/Si for U1–3 compared to 6 wt% of Fe and 0.48 of Al/Si for U4.

Such variability in IC might be caused by changes in the composition or supply of illite to the core. Histograms of the grain-size distribution of illite within the core do flatten, broaden, and shift to a slightly larger grain size with a high standard deviation (SD = 5.4) within U1 compare to U2–4 (Fig. 3). However, a similar elemental composition of illite is observed throughout U1–3 with a higher content of Fe (9–14 wt%) compared to U4 (6 wt%) and an Al/Si ratio of illite of 0.41–0.44 during U1–3, compared with 0.48 for U4 (Fig. 4b). There is no discernible appearance of detrital muscovite (Al/Si ≈ 1), biotite (Al/Si ≈ 0.3), or paragonite (Al/Si ≈ 1)33 that could affect the values of IC34 (Fig. 4b). Moreover, measured values of ICair (median) – ICgly (median) at each depth (0.14–0.52) correspond to the maximum 3% difference in smectite contents in illite/smectite mixed layers (I/S)34,35 (Supplementary Table 2). The variation in IC for the air-dried and ethylene-glycolated samples showed a similar trend with increasing depth, suggesting that the effect of smectite contents in I/S on IC is minimal in this study (Supplementary Fig. 3). Also, rare-earth element composition indicates that Holocene sediments (U1–3) are of the same source, which is different from the source at the LGM (U4) (Supplementary Fig. 4). These observations suggest that variations in IC during the Holocene cannot be explained simply by different sources of illite minerals or mineralogical variation, but rather by in situ alteration.

Previous observations of such diagenetic mineral alteration generally are reported in high temperature and pressure environments36, far from the conditions observed in sub-ice shelf sediments. Thus, we suggest here that biogeochemical redox-sensitive reactions, possibly by iron-reducing bacteria rather than high temperature and pressure, are the likely cause of the modification of the illite structure observed in U3. Microbial Fe reduction in 2:1 layered phyllosilicate structure results in the alteration of net negative charge, crystal lattice energy, cation exchange capacity, and distribution of Fe(II)–Fe(III) in the octahedral sheet37,38,39 that could modify the crystal domain size and structure39 responding in the IC16. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements on the bioreduced illite confirmed the alteration of illite structure through reductive dissolution and decrease in illite crystalline size24. Indeed, smaller illite domain packet size displayed where reducing condition is favored (Fig. 3), measuring a high value of half-height width of illite (high values in IC) (Fig. 2d). Other clay minerals may also undergo microbially induced changes that involve release of reduced iron; however, illite is the only clay mineral for which we can currently measure the crystallinity responding to alteration of crystal structure in various redox conditions25,40. Furthermore, the consequences of sediment oxygenation with the onset of full open marine conditions in U1 are clearly revealed by the decrease of IC and a change in selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of diffused, randomly ordered (U3) to discrete reflections (U1) (Fig. 3a, c), as illite alteration reactions cease.

Evidence for microbial alteration and implications

Significant positive correlations between the distribution/abundance of putative Fe-reducing bacteria and IC were observed in the core (r = 0.90 and 0.69, p < 0.05, Fig. 5). The major groups of bacteria present were identified as members of Comamonadaceae sp. (class Betaproteobacteria) and Desulfobacteraceaet sp. (class Deltaproteobacteria)22,23, comprising only minor components of the microbial community in the top of the core, but becoming abundant below 50 cm (mid-U2) (Fig. 5a). The genomic signatures (e.g., gene contents) supporting the presence of iron-reducing metabolisms in the family Comamonadaceae in our samples were not found from the microbial genome database in the GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome), indicating the occurrence of novel member with not-yet-known functions in those families. Nonetheless, the previous study22 suggested that the family Comamonadaceae is capable of reducing Fe in sediments (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, a recent study41 showed a possibility of anaerobic ammonium oxidation coupled to ferric Fe reduction by this family. The correlation between Desulfobacteraceae and illite alteration (Fig. 5c) may reflect either direct microbial Fe reduction42 or microbially influenced reductive dissolution of Fe-bearing minerals by hydrogen sulfide formed by sulfate-reducing bacteria43,44. Moreover, it was reported that Fe can be an electron acceptor during the reoxidation of H2S43. The distribution of Dehalococcoidetes sp. (phylum Chloroflexi) may reflect a tight coupling with Fe-reducing bacteria45; however, they are not considered to be a direct driver to change IC (Fig. 5d). Given the low temperatures at these sediment depths compared to where IC is normally observed, and the observed relationship between the presence of putative Fe-reducing bacteria and IC, we hypothesize that microbial activity is responsible for the alteration of illite observed in these sediments, although the exact mechanism of electron transfer by which this occurs is not yet constrained46,47. Nevertheless, the biogeochemical data described here indicate a clear link between microbial Fe respiration, alteration of illite crystallinity, and an increase in the Fe(II) content of illite under anoxic conditions. The relative amount of putative Fe-reducing bacteria diminishes abruptly in the sediments under occasionally open marine conditions (U1), where laminated sediment structures have been destroyed by oxygenation and resultant epibenthic community development. Although such psychrophilic Fe reduction of illite results in similar structural and chemical modification (Figs. 3 and 4) to what has been presented in previous studies of mesophilic13 and thermophilic reaction48, our data are the first observations in natural sediments to suggest a possible pathway for Fe reduction (and release to sediment porewaters as dissolved Fe) associated with microbial Fe respiration at low temperature21 in Antarctic regions19.

Sediment-derived Fe in the antarctic

Sediments as an important or even dominant Fe source for the surface oceans has gained traction in recent years, challenging the primacy of atmospheric supply49. This growing consensus of the importance of submarine sediment-derived Fe sources in fueling surface productivity has been driven both by models50 and by observations by the International GEOTRACES program, which have indicated transport of sediment-derived iron over 106 km in the open ocean51, including the Southern Ocean52. In the Antarctic, a number of recent studies have focused on the local importance of Fe from shelf sediments around Antarctica, suggesting that Fe sourced from sediments on the West Antarctic Peninsula is an important Fe source to coastal waters53,54,55. Sediment-derived Fe is also thought to be the dominant Fe source fueling blooms in the Ross and Amundsen Seas56,57, and near Antarctic island chains58.

The isotope signature of Fe is generally lighter at the depths of the Antarctic Intermediate Water in the Atlantic Sector of the Southern Ocean and S. Atlantic59,60, consistent with the possibility of long-distance transport of sediment-derived Fe of a reductive origin61,62 on the Antarctic Peninsula. Such an observation adds weight to the idea that microbial Fe(III) reduction in Fe-rich sediments on the Antarctic margins could play an important role in driving primary productivity in the Southern Ocean, especially near Antarctica. However, dissimilatory reductive dissolution of sediment release isotopically light Fe2+ is typically thought to involve Fe(III) minerals such as goethite, hematite, and ferrihydrite63,64. Here, we propose that illite may provide an additional substrate for microbial reduction that was previously thought to be largely inaccessible. This study opens the door for iron isotope studies in the future aiming to constrain the proportion of iron release from Fe(III) oxides as well as illite by this process if there is a signature isotope composition for this process. This may be especially important in the Antarctic, because illite (and clay minerals more generally) appears so prominently on the continental shelf around Antarctica14, and because redox dynamics are likely to be so intrinsically linked to ice shelf dynamics. Clay minerals comprise 10–30% of bulk Antarctic sediment14, and our experimental data suggest that ~4% of Fe may be released by psychrophilic microbial reduction of the clay mineral smectite (Supplementary Fig. 5). Together, these observations suggest that microbial alteration of Fe-bearing clay minerals corresponding to redox conditions in deglacial sediments may also play a role in generating Fe(II) in sediment porewaters, which could potentially be released to the water column. The strength of this flux is likely to change with ice shelf conditions.

Conceptual model for microbially enhanced Fe release from illite

Given the potential importance of the amount of Fe(II) that can be sourced from the microbe–mineral interactions, we have observed that it is important to consider this as a changing source of Fe(II) to the Southern Ocean as ice shelves retreat4. Our opportunistic core indicates that changes in ice shelf position and oxygenation of the core top can create a boundary to diffusive/advective export of sedimentary Fe(II) that forms from microbially driven IC downcore (Fig. 6). This process can also switch the flux of porewaters from the sediment from mainly diffusive to advective as the sediment is disturbed. Thus, the observed bioturbation at the surface of the core (Fig. 6a), although independent from continued microbially driven IC changes (Fig. 6b, c), will likely decrease the amount of Fe(II) sourced from the sediment. However, oxygenation of the surface sediments by bioturbation and bioirrigation as the ice shelf recedes or collapses might increase the advective or resuspended flux of iron from the sediments65,66. Thus, any feedback between ice shelf retreat and CO2 in the atmosphere would have to consider changes in both the form and quantity of iron coming from sub-ice shelf sediments. Between 2010 and 2016, the continent of Antarctica lost between 672 and 2254 km2 of grounded ice area9. Given the prominence of illite in Antarctic sediments, coupled with the likely decrease in Fe(II) diffusion to the water column, as these sediments are oxygenated and exposed to more vigorous open-ocean exchange (Fig. 6a), such accelerated loss of ice shelf-covered seafloor is likely to dramatically alter both the flux and speciation of dissolved Fe reaching the ocean, providing a new possible feedback between ice-shelf dynamics (Fig. 6b–e) and primary productivity in the Southern Ocean.

The core site experienced five different depositional settings. a Oxygenated and bioturbated sediment in open marine (170 to 5580 yr BP), b cCross-laminated layers over laminated sediment under sub-ice shelf (5580 to 7590 yr BP), c laminated sediment under sub-ice shelf (7590 to 11,030 yr BP), d diamict under subglacial (11,030 yr BP to Last Glacial Maximum), and (e) diamict in Last Glacial Maximum (APIS: Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet).

Methods

Geological location and sediment sampling

Sediment cores from the LIS-C embayment are exceedingly rare. The region is often inaccessible to ocean-going and ice-breaking research vessels, and as a result, has not been explored geologically to the extent of the lower latitude embayments of LIS-A and LIS-B. A marine geological expedition (ANA03C Cruise Expedition by the Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI)) was conducted in the LIS-A, LIS-B, and LIS-C embayments of northwestern Weddell Sea in 2013 (Fig. 1). LIS-C, the largest ice shelf in the Antarctic Peninsula (AP), has persisted since the LGM, but it has been thinning since the recent regional warming of AP8. A whole round core sample (238 cm below the seafloor) of marine sediment (EAP13-GC16B) was collected on the northwestern part of LIS-C embayment (66° 3.898′S, 60° 27.692′W, Fig. 1). The sediments underneath the sea ice in front of the LIS-C had not been exposed until a recent retreat of the calving front67. This core is unique because it contains a record of the complete depositional features during the Holocene without modifications. For these reasons, our core represents an excellent test for the capability of biogeochemical reactions to alter mineralogical characteristics through the Holocene. The Larsen Ice Shelf system is a climate-sensitive glacial system; the loss of other Larsen ice shelves (LIS-A, 1995; LIS-B, 2002) along the AP is one of the most dramatic environmental changes directly observed anywhere on Earth68.

Petrophysical properties

A half slab of 238 cm whole round core was examined by X-ray radiograph to investigate the sedimentary structures. The working half of the core was sampled every 4-cm depth interval for measurement of size fractions of clay (<2 μm), silt (>2 to <62.5 μm), and sand (>62.5 μm) following a conventional particle separation procedure69. Briefly, particles larger than 62.5 μm (gravel and sand) were separated from bulk sediment by wet sieving. For the fine fractions smaller than 62.5 μm (silt and clay), particles were settled down in a 1 L graduated cylinder for 3 days, and then the grain size was determined using Micrometrics Sedigraph 5100. Qualitative ordinal color scale (Munsell color chart) was used to define bedding distinct color variations in the core.

Isotopic composition

Forty-four subsamples (~50 mg of each sample) were collected into tin capsules to analyze isotopic composition of δ13C and δ15N in sediment with depths. Each sample was pretreated with 1 M of hydrochloric acid three times in order to completely remove carbonates, and then isotopic compositions with a precision of 0.2‰ were measured at the Stable Isotope Laboratory, GNS Science, Lower Hutt, New Zealand, using an Isoprime isotope ratio mass spectrometer, interfaced to an EuroEA elemental analyzer in continuous-flow mode (EA-IRMS).

Electron microscopy

TEM micrographs for the sediment with depths were recorded using JEOL JEM-2100F at Ewha Women’s University, Seoul. The TEM samples were prepared following the impregnation procedure for LR White resin70 to minimize the confusion of selecting 10 Å illite packets from the collapsed hydrous clay minerals, such as smectite, displaying the same spacings under the high-energy TEM beam. Illite layers were confirmed by SAED patterns with the strongest Bragg reflections of 1.0, 0.5, and 0.33 nm. The TEM specimens were then sectioned with 700 Å in thickness using a diamond knife microtome (ULTRACUT TCT; Leica, installed at the Korea Basic Science Institute, KBSI). Transmission electron microscopy-electron energy loss spectroscopy (TEM-EELS) was also applied to quantify the oxidation states of Fe in illite structure as a function of the integral ratio of Fe L3/L271 using a TECHNAI F30 ST TEM at the KBSI, Seoul. The operational conditions for EELS acquisition were an energy dispersion of 0.1 eV/channel, entrance aperture of 2.0 mm, and the full-width at half-maximum to 1.0 eV for the zero-loss peak calibration. The statistical optimum signal-window parameters for the integral ratio of Fe-L2,3 edges were calculated using the Gatan Inc.’s Digital MicrographTM software. The backgrounds were removed from EELS spectra by Double arctan functions and Standard power law71.

X-ray diffractometer

XRD analyses were performed on air-dried clay sample (<2 μm) with each depth at a scan speed of 1°/min with a Rigaku Miniflex II automated diffractometer utilizing Cu-Kα radiation at Yonsei University, Seoul. Clay size fraction samples were dispersed in distilled water (0.7 mg/mL) and put in an ultrasonic water bath for 30 s to prevent flocculation of particles. Then, air-dried samples were made by pipetting sediment dispersions onto slide glasses for XRD analysis72. IC, also known as Kübler index, comprises of the half-height width of illite 10-Å peak from XRD profiles73 utilizing the Search-Match and OriginPro8 software after the background was removed by Chebyshev polynomial with ≤20 coefficients, and the pseudo-Voigt profile function proposed by Thompson et al. 74. IC was originally referred to as the Weaver index75 that reflects the X-ray scattering domain size and structural distortions16, measuring the crystal alterations76. Three independent sets of XRD profiles were collected in order to reduce the errors in the measurements. Semi-quantitative evaluations of clay minerals were measured after the glycolation treatment. The relative percentage of each clay mineral was calculated using weighting factors77.

DNA extraction, microbial community composition

Genomic DNA was extracted from sediment samples every 2 cm from top to 20 cm and every 5 cm below 20 cm (~0.5 g of each sample) using the FastDNA Spin Kit for soil (MP Biomedicals). The quantity of genomic DNAs was measured by Picogreen fluorometry. Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes of prokaryote (Bacteria and Archaea) were performed using primers Uni787F and Uni1391R78. We adopted the PCR cycling conditions according to Jorgensen et al. 78, except for applying the nested PCR, in order to minimize PCR bias. PCR amplicon pyrosequencing sequences were processed using the QIIME software package, ver. 1.879. First, raw flowgram data were filtered and denoized by the AmpliconNoise software, version 1.2980, using the platform option for FLX titanium sequence data implemented in QIIME. Sequences were clustered based on operational taxonomic units at 97% similarity using UCLUST81 and classified using the 16S rRNA gene sequence reference database GreenGenes 13_882. To avoid effects of different sample sizes for estimating diversity comparisons among prokaryotic communities, sequences were resampled to the smallest library83.

Bacterial culture and experimental procedure

Psychrophilic bacteria (Shewanella vesiculosa 21939, 21996 and Shewanella frigidimarina 21881) known as cold-tolerant and cold-adapted facultative FeRB46,84 were isolated from King George Island in western Antarctica by KOPRI. Psychrophilic bacteria were cultured in Luria–Bertani broth (LB) liquid medium aerobically for 7 days at 15 °C to increase cell concentration and activity. The culture was then washed three times with 0.1 mM NaCl solution to remove the residual LB medium, and the washed cells were re-incubated anaerobically for 7 days in liquid M1 medium85 with Fe(III)-citrate (34.5 mM) as an electron acceptor and Na-lactate (20 mM) as an electron donor in order to adapt Fe respiration. The solution was buffered by MOPS (3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid) to maintain a pH of 7. The incubated cells were finally washed three times with 0.1 mM NaCl solution to remove residual Fe(III)-citrate and M1 medium. Cells were then inoculated in the liquid M1 medium with nontronite (5 g/L) in each set as an electron acceptor and Na-lactate (20 mM) as an electron donor. Control samples were treated identically to experimental ones, except no bacteria to compare the microbial effect on Fe reduction. A sample of 100 mL of this suspension in each serum bottle was placed in the incubator at 4 °C for up to 4 months.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The source data underlying figures and Supplementary Material are provided as a Supplementary Data file. Any other information that supports data interpretation is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

De Baar, H. J. et al. Importance of iron for plankton blooms and carbon dioxide drawdown in the Southern Ocean. Nature 373, 412–415 (1995).

Martin, J. H., Gordon, R. M. & Fitzwater, S. E. Iron in Antarctic waters. Nature 345, 156–158 (1990).

Kohfeld, K. E. & Ridgwell, A. Glacial-interglacial variability in atmospheric CO2. Surf. Ocean Low Atmosphere Process. 187, 251–286 (2009).

Martínez-García, A. et al. Iron fertilization of the Subantarctic Ocean during the last ice age. Science 343, 1347–1350 (2014).

Arrigo, K. R., van Dijken, G. L. & Strong, A. L. Environmental controls of marine productivity hot spots around Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 5545–5565 (2015).

Vaughan, D. G. et al. Recent rapid regional climate warming on the Antarctic Peninsula. Clim. Change 60, 243–274 (2003).

Mulvaney, R. et al. Recent Antarctic Peninsula warming relative to Holocene climate and ice-shelf history. Nature 489, 141–144 (2012).

Shepherd, A., Wingham, D., Payne, T. & Skvarca, P. Larsen ice shelf has progressively thinned. Science 302, 856–859 (2003).

Konrad, H. et al. Net retreat of Antarctic glacier grounding lines. Nat. Geosci. 11, 258 (2018).

Brachfeld, S. et al. Holocene history of the Larsen-A Ice Shelf constrained by geomagnetic paleointensity dating. Geology 31, 749–752 (2003).

Leventer, A. et al. Marine sediment record from the East Antarctic margin reveals dynamics of ice sheet recession. GSA Today 16, 4 (2006).

Gorski, C. A., Klüpfel, L. E., Voegelin, A., Sander, M. & Hofstetter, T. B. Redox properties of structural Fe in clay minerals: 3. Relationships between smectite redox and structural properties. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 13477–13485 (2013).

Kim, J., Dong, H., Seabaugh., J., Newell, S. W. & Eberl, D. D. Role of microbes in the smectite-to-illite reaction. Science 303, 830–832 (2004).

Petschick, R., Kuhn, G. & Gingele, F. Clay mineral distribution in surface sediments of the South Atlantic: sources, transport, and relation to oceanography. Mar. Geol. 130, 203–229 (1996).

Cashman, K. V. & Ferry, J. M. Crystal size distribution (CSD) in rocks and the kinetics and dynamics of crystallization. Contrib. Min. Petr. 99, 401–415 (1988).

Eberl, D. & Velde, B. Beyond the Kübler index. Clay Miner. 24, 571–577 (1989).

Wang, Q. & Yang, S. Clay mineralogy indicates the Holocene monsoon climate in the Changjiang (Yangtze River) Catchment, China. Appl. Clay Sci. 74, 28–36 (2013).

Pandarinath, K. Clay minerals in SW Indian continental shelf sediment cores as indicators of provenance and palaeomonsoonal conditions: a statistical approach. Int. Geol. Rev. 51, 145–165 (2009).

Mikucki, J. A. et al. A contemporary microbially maintained Subglacial ferrous “ocean”. Science 324, 397–400 (2009).

Karl, D. et al. Microorganisms in the accreted ice of Lake Vostok, Antarctica. Science 286, 2144–2147 (1999).

Montross, S. N., Skidmore, M., Tranter, M., Kivimäki, A. L. & Parkes, R. J. A microbial driver of chemical weathering in glaciated systems. Geology 41, 215–218 (2013).

Emerson, D., Scott, J. J., Benes, J. & Bowden, W. B. Microbial iron oxidation in the arctic tundra and its implications for biogeochemical cycling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 8066–8075 (2015).

Reyes, C. et al. Bacterial communities potentially involved in iron-cycling in Baltic Sea and North Sea sediments revealed by pyrosequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 92, fiw054 (2016).

Dong, H. et al. Microbial reduction of structural Fe (III) in illite and goethite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 1268–1276 (2003).

Zhang, J. et al. Microbial reduction of Fe (III) in illite–smectite minerals by methanogen Methanosarcina mazei. Chem. Geol. 292, 35–44 (2012).

Froelich, P. N. et al. Early oxidation of organic matter in pelagic sediments of the eastern equatorial Atlantic: suboxic diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 43, 1075–1090 (1979).

Domack, E. W., Ishman, S. E., Stein, A. B., McClennen, C. E. & Jull, A. T. Late Holocene advance of the Müller Ice Shelf, Antarctic Peninsula: sedimentological, geochemical and palaeontological evidence. Antarct. Sci. 7, 159–170 (1995).

Domack, E. W., Burnett, A., & Leventer, A. in Antarctic Peninsula Climate Variability: Historical and Paleoenvironmental Perspectives (ed. Domack, E.) 1–13 (AGU, Washington, 2003).

Subt, C. et al. Sub‐ice shelf sediment geochronology utilizing novel radiocarbon methodology for highly detrital sediments. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 18, 1404–1418 (2017).

Domack, E. et al. Cruise reveals history of Holocene Larsen ice shelf. Eos Trans. Am. 82, 13–17 (2001).

Domack, E. et al. Stability of the Larsen B ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula during the Holocene epoch. Nature 436, 681–685 (2005).

Evans, J., Pudsey, C. J., ÓCofaigh, C., Morris, P. & Domack, E. Late Quaternary glacial history, flow dynamics and sedimentation along the eastern margin of the Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 741–774 (2005).

Dixon, J. B., Weed, S. B. & Parpitt, R. Minerals in soil environments. Soil Sci. 150, 562 (1990).

Abad, I., Nieto, F. & Millán, J. in Diagenesis and Low-Temperature Metamorphism, Theory, Methods and Regional Aspects, Seminarios Sociedad Espanola: Sociedad Espanola Mineralogia, (eds Nieto, F. & Millán, J. J.) 53–64 (Sociedad Espanola Mineralogia, Jaén, 2007).

Jaboyedoff, M., Bussy, F., Kübler, B. & Thelin, P. Illite “crystallinity” revisited. Clays Clay Miner. 49, 156–167 (2001).

Eberl, D. & Hower, J. Kinetics of illite formation. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 87, 1326–1330 (1976).

Komadel, P., Madejová, J. & Stucki, J. W. Structural Fe (III) reduction in smectites. Appl. Clay Sci. 34, 88–94 (2006).

Stucki, J. W. & Kostka, J. E. Microbial reduction of iron in smectite. C R Geosci. 338, 468–475 (2006).

Sainz-Díaz, C. I., Timón, V., Botella, V., Artacho, E. & Hernández-Laguna, A. Quantum mechanical calculations of dioctahedral 2: 1 phyllosilicates: effect of octahedral cation distributions in pyrophyllite, illite, and smectite. Am. Mineral. 87, 958–965 (2002).

Jaisi, D. P., Dong, H. & Liu, C. Influence of biogenic Fe (II) on the extent of microbial reduction of Fe (III) in clay minerals nontronite, illite, and chlorite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 1145–1158 (2007).

Bao, P. & Li, G. X. Sulfur-driven iron reduction coupled to anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 6691–6698 (2017).

Enning, D. & Garrelfs, J. Corrosion of iron by sulfate-reducing bacteria: new views of an old problem. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 1226–1236 (2014).

Dos Santos Afonso, M. & Stumm, W. Reductive dissolution of iron (III)(hydr) oxides by hydrogen sulfide. Langmuir 8, 1671–1675 (1992).

Li, Y. L. et al. Iron reduction and alteration of nontronite NAu-2 by a sulfate-reducing bacterium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 3251–3260 (2004).

Wei, N. & Finneran, K. T. Influence of ferric iron on complete dechlorination of trichloroethylene (TCE) to ethene: Fe (III) reduction does not always inhibit complete dechlorination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 7422–7430 (2011).

Bozal, N. et al. Shewanella vesiculosa sp. nov., a psychrotolerant bacterium isolated from an Antarctic coastal area. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59, 336–340 (2009).

Jaisi, D. P., Eberl, D. D., Dong, H. & Kim, J. The formation of illite from nontronite by mesophilic and thermophilic bacterial reaction. Clays Clay Miner. 59, 21–33 (2011).

Zhang, G., Dong, H., Kim, J. & Eberl, D. Microbial reduction of structural Fe3+ in nontronite by a thermophilic bacterium and its role in promoting the smectite to illite reaction. Am. Mineral. 92, 1411–1419 (2007).

Elrod, V. A., Berelson, W. M., Coale, K. H. & Johnson, K. S. The flux of iron from continental shelf sediments: a missing source for global budgets. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L12307 (2004).

Tagliabue, A., Aumont, O. & Bopp, L. The impact of different external sources of iron on the global carbon cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 920–926 (2014).

Schlitzer, R. et al. The GEOTRACES Intermediate Data Product 2017. Chem. Geol. 493, 210–223 (2018).

Klunder, M. et al. Dissolved Fe across the Weddell Sea and Drake Passage: impact of DFe on nutrient uptake. Biogeosciences 11, 651–669 (2014).

Annett, A. L. et al. Comparative roles of upwelling and glacial iron sources in Ryder Bay, coastal western Antarctic Peninsula. Mar. Chem. 176, 21–33 (2015).

De Jong, J. et al. Natural iron fertilization of the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean by continental shelf sources of the Antarctic Peninsula. J. Geophys. Res. 117, G01029 (2012).

Sherrell, R. M. et al. A ‘shallow bathtub ring’of local sedimentary iron input maintains the Palmer Deep biological hotspot on the West Antarctic Peninsula shelf. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20170171 (2018).

Gerringa, L. J. et al. Iron from melting glaciers fuels the phytoplankton blooms in Amundsen Sea (Southern Ocean): Iron biogeochemistry. Deep Sea Res. Pt. II 71, 16–31 (2012).

Sedwick, P. N. et al. Early season depletion of dissolved iron in the Ross Sea polynya: implications for iron dynamics on the Antarctic continental shelf. J. Geophys. Res. 116, C12019 (2011).

Planquette, H. et al. Fluxes of particulate iron from the upper ocean around the Crozet Islands: a naturally iron‐fertilized environment in the Southern Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 25, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GB004059 (2011).

Conway, T. M., John, S. & Lacan, F. Intercomparison of dissolved iron isotope profiles from reoccupation of three GEOTRACES stations in the Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Chem. 183, 50–61 (2016).

Abadie, C. et al. Iron isotopes reveal distinct dissolved iron sources and pathways in the intermediate versus deep Southern Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 858–863 (2017).

Homoky, W. et al. Pore-fluid Fe isotopes reflect the extent of benthic Fe redox recycling: evidence from continental shelf and deep-sea sediments. Geology 37, 751–754 (2009).

John, S. G., Mendez, J., Moffett, J. & Adkins, J. The flux of iron and iron isotopes from San Pedro Basin sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 93, 14–29 (2012).

Icopini, G. et al. Iron isotope fractionation during microbial reduction of iron: the importance of adsorption. Geology 32, 205–208 (2004).

Crosby, H. A., Roden, E. E., Johnson, C. M. & Beard, B. L. The mechanisms of iron isotope fractionation produced during dissimilatory Fe (III) reduction by Shewanella putrefaciens and Geobacter sulfurreducens. Geobiology 5, 169–189 (2007).

Santos, I. R., Eyre, B. D. & Huettel, M. The driving forces of porewater and groundwater flow in permeable coastal sediments: a review. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 98, 1–15 (2012).

Aquilina, A. et al. Hydrothermal sediments are a source of water column Fe and Mn in the Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 137, 64–80 (2014).

Survey, G., & Ferrigno, J. G. Coastal-Change and Glaciological Map of the Larsen Ice Shelf Area, Antarctica, 1940–2005 (USGS, 2008).

Vaughan, D. & Doake, C. Recent atmospheric warming and retreat of ice shelves on the Antarctic Peninsula. Nature 379, 328–331 (1996).

Jones, K., McCave, I. & Patel, D. A computer‐interfaced sedigraph for modal size analysis of fine‐grained sediment. Sedimentology 35, 163–172 (1988).

Kim, J. W., Peacor, D. R., Tessier, D. & Elsass, F. A technique for maintaining texture and permanent expansion of smectite interlayers for TEM observations. Clays Clay Miner. 43, 51–57 (1995).

Van Aken, P., Liebscher, B. & Styrsa, V. Quantitative determination of iron oxidation states in minerals using Fe L 2, 3-edge electron energy-loss near-edge structure spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Miner. 25, 323–327 (1998).

Yang, K. et al. Smectite, illite, and early diagenesis in South Pacific Gyre subseafloor sediment. Appl. Clay Sci. 134, 34–43 (2016).

Kübler, B. Les argiles, indicateurs de métamorphisme. Rev. Inst. Franc. Pétrole 19, 1093–1112 (1964).

Thompson, P., Cox, D. & Hastings, J. Rietveld refinement of Debye–Scherrer synchrotron X-ray data from Al2O3. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 20, 79–83 (1987).

Weaver, C. E. Possible uses of clay minerals in search for oil. AAPG Bull. 44, 1505–1518 (1960).

Roberts, B. & Merriman, R. The distinction between Caledonian burial and regional metamorphism in metapelites from North Wales: an analysis of isocryst patterns. J. Geol. Soc. 142, 615–624 (1985).

Biscaye, P. E. Mineralogy and sedimentation of recent deep-sea clay in the Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas and oceans. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 76, 803–832 (1965).

Jorgensen, S. L. et al. Correlating microbial community profiles with geochemical data in highly stratified sediments from the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E2846–E2855 (2012).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Quince, C., Lanzen, A., Davenport, R. J. & Turnbaugh, P. J. Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinforma. 12, 38 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461 (2010).

Werner, J. J. et al. Impact of training sets on classification of high-throughput bacterial 16s rRNA gene surveys. ISME J. 6, 94–103 (2012).

Kirchman, D. L., Cottrell, M. T. & Lovejoy, C. The structure of bacterial communities in the western Arctic Ocean as revealed by pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA genes. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 1132–1143 (2010).

Bowman, J. P. et al. Diversity and association of psychrophilic bacteria in Antarctic sea ice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 3068–3078 (1997).

Myers, C. R. & Nealson, K. H. Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science 240, 1319 (1988).

Acknowledgements

The present research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (NRF-2018R1A2B6002036) and Antarctic Project of KOPRI (PE19030) to J.W.K. We thank the science parties and crews of KOPRI icebreaker R/V Araon for their extraordinary efforts to collect samples and data processing (KOPRI ANA03C). Especially, we express our deep appreciation to the late Dr. E. Domack and Dr. Yoon as co-chief scientists of Weddell Sea expedition for their tremendous contributions to this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. J.K. designed the overall research concept, data interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. J.J. produced data, including TEM data process and microbial diversity information with the help of K.Y. and C.Y.H. K.-C.Y., H.I.Y., and J.I.L. interpreted the sedimentary facies and depositional environments. B.E.R. and C.S. interpreted the chronology of the core, and B.E.R. and T.M.C. developed the concept of a possible Fe source. B.E.R. and J.J. conceived and designed the conceptual model of porewater iron transitions through time.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Martyn Tranter and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, J., Yoo, KC., Rosenheim, B.E. et al. Microbial Fe(III) reduction as a potential iron source from Holocene sediments beneath Larsen Ice Shelf. Nat Commun 10, 5786 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13741-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13741-x

This article is cited by

-

Higher diversity of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria based on soxB gene sequencing in surface water than in spring in Wudalianchi volcanic group, NE China

International Microbiology (2024)

-

Uniquely low stable iron isotopic signatures in deep marine sediments caused by Rayleigh distillation

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Spatial variations of authigenic beryllium isotopes in surface sediments of the Antarctic oceans: a proxy for sea ice dynamics and sedimentary environments

Geosciences Journal (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.