Abstract

Two-dimensional heterostructures combined with vertical geometries are candidates to probe and utilize the physical properties of atomically-thin materials. The vertical configuration enables a unique form of hot-carrier spectroscopy as well as atomic-scale devices. Here, we present the room-temperature evolution of heteroepitaxial perovskite hot-electron transistors using a SrRuO3 base down to the monolayer limit (∼4 Å). As a fundamental electronic probe, we observe an abrupt transition in the hot-electron mean free path as a function of base thickness, coinciding with the thickness-dependent resistive transition. As a path towards devices, we demonstrate the integrated synthesis of perovskite one-dimensional electrical edge contacts using water-soluble and growth-compatible Sr3Al2O6 hard masks. Edge-contacted monolayer-base transistors exhibit on/off ratios reaching ∼108, complete electrostatic screening by the base manifesting pure hot-electron injection, and excellent scaling of the output current density with device dimensions. These results open new avenues for incorporating emergent phenomena at oxide interfaces and in heterostructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Along with exfoliated two-dimensional (2D) materials1,2,3,4,5, atomic-scale artificial perovskite oxide heterostructures offer exciting opportunities6,7 for new devices and experimental probes of quantum materials. Specifically, designing vertical architectures incorporating these materials has unique advantages. It effectively utilizes their atomically thin nature by actively setting the channel length to an atomic scale, which would be an enabling pathway for fast electronics8, which is technically challenging in planar devices. More importantly, the perpendicular geometry can diversify functionalities in fundamental studies and applications by integrating layers with a wide range of physical properties in an interface-specific manner. For example, hot-electron transport across interfaces can be used to surpass fundamental thresholds9,10, such as the thermodynamic Shockley–Queisser limit in solar cells. In oxide heterostructures, hot-electron spectroscopy11 would be an invaluable tool to investigate the nanometer scale electronic reconstructions that are often observed at interfaces and in confined geometries7.

In pursuit of this approach, we demonstrate the evolution of a highly robust vertical hot-electron transistor (HET)12 based on perovskite oxide heterostructures down to the monolayer-base limit, consisting of a SrTiO3 emitter (both Nb-doped and undoped), atomically thin SrRuO3 base, and Nb:SrTiO3 (001) collector (Fig. 1; see the Methods section).

Schematics and working principle of the perovskite hot-electron transistor (HET). a The crystal structure of the atomically thin HET with a SrTiO3 emitter/SrRuO3 base/Nb:SrTiO3 (001) collector trilayer. b Schematic illustration of the HET energy band diagram in the off-state (left) and in the common-base forward-active mode (right). In device operation, hot electrons are injected across the forward-biased base–emitter (BE) junction, traverse across the grounded base, and are collected across the reverse-biased base–collector (BC) junction. c Device process flow of the HET with laterally staggered electrical contacts.

Results

Heterostructure fabrication and junction characteristics

In device operation, hot electrons are injected out-of-plane across the forward-biased base–emitter (BE) junction, traverse the grounded base, and are collected across the reverse-biased base–collector (BC) junction. We first focus on devices with conventional laterally staggered surface contacts. The heteroepitaxial trilayer shows epitaxial and atomically flat surface topographies with the perovskite step-and-terrace structure of the underlying substrate, as seen by atomic force microscopy (AFM) and reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED) patterns (Fig. 2a–e). Accordingly, both interfaces form Schottky junctions following the thermionic emission model, evident from the rectifying current-voltage characteristics with constant Schottky barrier height ϕ and ideality factor η near unity down to the monolayer limit (Fig. 2f, g). This is remarkable considering that only a single unit cell (u.c.) of SrRuO3 (∼4 Å) is responsible for the Schottky junction formation at both interfaces.

Heterostructure fabrication and room-temperature junction characteristics. a RHEED intensity oscillations for the growth of SrRuO3 base. In situ RHEED patterns of b Nb:SrTiO3 (001) and c SrRuO3. AFM topographies of d 8 unit cell (u.c.) SrRuO3, and e SrTiO3 thin films, showing a clear perovskite step-and-terrace surface structure. The scale bar is 1 μm. f Current-voltage characteristics of the BC and BE Schottky junctions, for various SrRuO3 thicknesses down to the monolayer limit. g Extracted BC and BE junction Schottky barrier height ϕ (top) and ideality factor η (bottom). The solid lines are the mean values.

Electrical characteristics of variable thickness SrRuO3 HETs

The common-base and common-emitter output characteristics of these devices show clear transconductance down to the monolayer limit (Fig. 3a–d). As the base becomes thinner, more hot electrons overcome ϕBC due to less scattering in the base; accordingly, the collector current density JC increases exponentially (Fig. 3b, inset). In general, an atomically thin base could be prone to the formation of pinhole and edge defects which electrostatically couple the emitter and the collector via a semiconducting channel, inducing permeable-base transistor operation13,14 governed by the drift-diffusive transport of Fermi-level electrons, as opposed to hot-electron transport. To rule out this possibility, we demonstrate that the metal base in our HETs completely screens the electric field and electrically isolates the emitter and the collector, by the measurement of constant voltage feedback curves (Fig. 3a–c).

Room-temperature electrical characterization of variable thickness SrRuO3 HETs. Common-base output characteristics (top) and voltage feedback (bottom) for SrRuO3 thicknesses of a 10 u.c. and b 7 u.c., as JE is increased from 0 to 5.36 mA cm−2, in 1.34 mA cm−2 steps; and c 1 u.c., as JE is increased from 0 to 2.68 μA cm−2, in 0.67 μA cm−2 steps. The inset to a shows the region where clear transconductance can be seen for 10 u.c. SrRuO3 thickness. The inset to b shows a schematic illustration of the increase of hot-electron transfer as the base becomes thinner. The constant voltage feedback curves in the common-base output characteristics demonstrate the complete electrostatic screening by the base metal. d Common-emitter output characteristics for 1 u.c. SrRuO3 thickness, as JB is increased from 0 to 2.68 μA cm−2, in 0.67 μA cm−2 steps. e Device statistics on common-base current gain α. For a specified SrRuO3 thickness, each bar represents a single device and each color represents a distinct sample from a different fabrication run. f Common-base transfer characteristics for 1 u.c. SrRuO3 thickness with VCB ranging from 0.0 to 0.6 V, in 0.1 V steps. VEB required for the onset of JC is independent of VCB, indicating pure HET operation.

The common-base transfer characteristics further corroborate this complete screening in the base by showing that the VEB required for the onset of JC is independent of VCB (Fig. 3f). Considering the Thomas–Fermi screening length LTF of ∼2 Å in SrRuO3 at both interfaces, it is significant that the transistor still operates as a pure HET with only a single u.c. of SrRuO3. The monolayer common-base current gain α ∼ 0.12 and common-emitter current gain β ∼ 0.14 follow the expected relation β = α/(1–α). After optimizing the processing conditions, our devices show 100% HET yield with exceptionally high stability and reproducibility for >100 devices examined (Fig. 3e). This is in contrast to prior work using a manganite base with low HET yield and dominantly permeable-base devices14. We attribute this important difference to the perfect registry of SrRuO3 with the underlying substrate; namely, the common Sr cation throughout the trilayer, with interfaces free of polar electrostatic boundary conditions15,16.

Probing the fundamental characteristics of hot electrons

The extremely high reliability of these HETs allows the experimental determination of hot-electron parameters, which were not previously accessible due to low yield and device-to-device fluctuations14. As shown in Fig. 4a–c, we observe the systematic thickness-dependent evolution of α over a wide range of ∼7 orders of magnitude. Note that these devices were optimized for stability, not output current density, by incorporating a thick undoped SrTiO3 emitter (Fig. 1). This avoided the growth-to-growth carrier density fluctuations of doped SrTiO3, which would obscure the intrinsic response for thicker SrRuO3. The exponential trend of α can be parametrized by the hot-electron mean free path λH as12

where t is the SrRuO3 thickness, α0 is α extrapolated to t = 0 u.c., and λH,B (λH,I) is the bulk (interfacial) hot-electron mean free path. The fact that α fits very well the exponential form self-consistently confirms HET operation, and highlights the ability to control SrRuO3 thickness on the atomic level. These results indicate that SrRuO3 is homogeneous with λH,I ∼ 0.3 ± 0.01 u.c. up to 3 u.c. However, two distinct regions exist for thicker SrRuO3: the interfacial region with λH,I, and the ‘bulk’ region away from the interface with λH,B ∼ 1.4 ± 0.03 u.c., in good correspondence to recent studies using ballistic electron emission microscopy across the vacuum/SrRuO3 interface17.

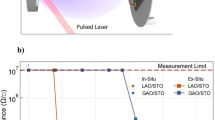

Probing the fundamental characteristics of hot electrons down to the monolayer limit of the HET at room temperature. Common-base transfer characteristics for different SrRuO3 thicknesses at VCB = 0 V, plotted as a VEB versus JC, and b JE versus JC. c Common-base current gain α (red open circles) at VCB = 0 V and in-plane conductivity σ of the SrRuO3/SrTiO3 (001) heterostructures (blue open circles) as a function of SrRuO3 thickness at room temperature. α spans a wide range of ~7 orders of magnitude and self-consistently follows an exponential trend, illustrating the HET operation of the devices. Two distinct exponential regimes exist as a function of SrRuO3 thickness, where the deduced hot-electron mean free path λH is ~0.3 ± 0.01 u.c. from the data up to 3 u.c., and ~1.4 ± 0.03 u.c. from the data for thicker base. Below 3 u.c., fractional coverage devices smoothly interpolate. The red solid lines are best linear fits to the two regimes. d λH near the center of the SrRuO3 base layer (red solid line) and Fermi-electron mean free path λF (blue open circles) as a function of SrRuO3 thickness. The quasi-universal thickness-dependent metal–insulator transition is evident both from λH and λF across the same critical thickness. The blue solid line is a fit assuming a dominant surface/interface scattering (see text). The inset shows the thickness-dependent in-plane resistivity ρ as a function of temperature T for SrRuO3/SrTiO3 (001) heterostructures.

The abrupt transition in λH at 3 u.c. is quite reminiscent of the commonly observed resistivity transition for ultrathin SrRuO318,19,20,21. While there are some variations in the observed critical thickness, and debate on its origin, we see the same transition in our films. Figure 4c shows the thickness-dependent evolution of the room-temperature in-plane conductivity for identically grown samples on an undoped substrate. Notably, for 3 u.c. and below, the temperature dependence is insulating, while for 4 u.c. and above, increasingly bulk-like metallic temperature dependence is observed (Fig. 4d, inset).

From a fundamental perspective, λH has a rather interesting comparison to that for conventional transport, λF, the Fermi-electron mean free path. λF can be estimated from the resistivity ρ, which can be expressed via Boltzmann transport as \(\rho = 3{\uppi}^2\hbar /q^2k_{\mathrm{F}}^2\lambda _{\mathrm{F}}\), where ħ is the reduced Planck’s constant, q is the elementary charge, and kF is the Fermi wave vector22. Figure 4d shows the deduced thickness-dependent λF at room temperature. As previously noted, the smooth decrease of λF down to 4 u.c. arises from enhanced surface/interface scattering20. Even in the atomistically clean limit, surface/interface scattering impacts the in-plane transport of ultrathin films23, including diffuse scattering at step edges, whereby λF can be expressed in terms of t using Matthiessen’s rule as \({\mathrm{1}}/\lambda _{\mathrm{F}} = 1/\lambda _{{\mathrm{F,B}}} + 1/t_0t\), where λF,B is the bulk Fermi-electron mean free path, and t0 is the surface/interface scattering constant. Estimating λF,B as λF for t = 60 u.c., λF fits well this functional form down to 4 u.c. but then drastically decreases in the thinner films with insulating temperature dependence.

As has been previously emphasized, the extremely short λF,B (300 K) ∼ 0.6 u.c. in SrRuO3 is highly inconsistent with coherent transport in conventional metals22,24, and this ‘badly metallic’ behavior is a characteristic feature of strongly correlated metals under much current investigation25. Here we find that λH,B exceeds our estimate for λF,B by a factor of ∼2.3 (Fig. 4d). This enhancement could originate from Ru 4d electrons effectively screening the inelastic electron–electron scattering of hot electrons26. Note that λH,B can be isolated from surface/interface scattering, as indicated by its constant thickness dependence above the sharp transition between 3 u.c. and 4 u.c.—this is a unique advantage of these thickness-dependent hot-electron experiments, enabling a direct measure of fundamental scattering mechanisms without surface/interface contributions. The surprising enhancement of λH,B with respect to λF,B suggests that further hot-electron spectroscopic studies of strongly correlated metals would provide valuable insights in this relatively unexplored regime.

Perovskite one-dimensional electrical edge contacts

We turn now to considerations relevant for the potential development of monolayer heterostructures for practical devices. While there are several important issues that need to be addressed, a central obstacle is the low output current density in the HETs presented thus far (JC ∼ μA cm−2). Two significant contributions are the high emitter resistance introduced via thick undoped SrTiO3 (needed for device stability investigating the thick-base regime, but which limits hot-electron injection), and the in-plane base series resistance arising from the laterally staggered contact geometry, which becomes increasingly dominant in the monolayer limit. In order to address these issues, we can thin down and dope the emitter, which readily improves the emitter resistance by orders of magnitude15,27,28. Furthermore, we demonstrate here the synthesis of a perovskite one-dimensional electrical edge contact, in analogy to that recently developed for 2D materials29, using a water-soluble and growth-compatible Sr3Al2O6 hard mask layer30 (Fig. 5a; see the Methods section). The Sr3Al2O6 layer not only bypasses aggressive lift-off processes, but also is stable at high growth temperatures and oxidizing conditions, allowing for the corresponding growth of the perovskite edge contact.

Room-temperature electrical characterization of monolayer-base HETs with a perovskite one-dimensional electrical edge contact. a Schematic of the perovskite edge contact fabrication process using a water-soluble and growth-compatible Sr3Al2O6 hard mask layer30. RE (RB) is the emitter (base) radius. b Common-base output characteristics (top) and voltage feedback (bottom), as JE is increased from 0 to 0.2 A cm−2, in 0.05 A cm−2 steps. c Common-emitter output characteristics, as JB is increased from 0 to 0.2 A cm−2, in 0.05 A cm−2 steps. d Common-base transfer characteristics with VCB ranging from 0.0 to 0.6 V, in 0.1 V steps. RE is 9 μm for the devices shown in b through d. e On/off current ratio as a function of VCB ranging from 0.0 to 0.6 V, in 0.1 V steps. Each panel represents a different device. f On/off current ratio averaged over VCB ranging from 0.0 to 0.6 V (top) and common-base current gain α (bottom) for devices shown in e. The red solid line represents α = 0.35, each bar represents a different device, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. The blue, green, and yellow solid bars in e and f represent devices with RE = 40, 20, and 9 μm, respectively. g JC as a function of RE at VCB = 0 V and VEB = −5 V. The error bars represent the standard deviations. The data (red open circles) self-consistently scale with the residual base resistance underneath the emitter as JC ~ 1/RE (red solid line)31.

As a result, the monolayer-base devices improved significantly: JC increased by ∼5 orders of magnitude; on/off current ratios reached ∼100,000,000; and α increased threefold to ∼0.35, with a corresponding enhancement of β to ∼0.54 (Fig. 5). Pure HET operation is evident from the voltage feedback curves and the transfer characteristics as discussed previously (Fig. 5b, d). Most importantly, we find that JC self-consistently scales with the residual base resistance underneath the emitter as 1/RE (RE is the emitter radius)31, which is very favorable to device downscaling (Fig. 5g). This confirms that the perovskite edge contact effectively minimizes the base series resistance by placing the contact at the edge of the monolayer base/emitter interface, and should enable high current density in sub-micron devices. Furthermore, the edge contact method developed here should be broadly useful for a wide range of oxide heterostructure devices.

Methods

Heterostructure fabrication and device processing

The heteroepitaxial trilayer was fabricated using pulsed laser deposition with a 248 nm KrF excimer laser using TiO2-terminated Nb:SrTiO3 (001) substrates (0.01 wt% Nb dopant concentration). SrRuO3 base (1 u.c. to 15 u.c.) was grown in 100 mTorr O2. The base thickness was controlled on the atomic scale by monitoring the in situ RHEED oscillations, where one oscillation corresponds to a single u.c. Coherent RHEED oscillations throughout the growth indicate high quality layer-by-layer growth of the SrRuO3. In particular, the growth of SrRuO3 is interrupted every 4 u.c. for thicker films so that the adatoms on the surface can sufficiently rearrange, and preserve the step-and-terrace structure of the underlying substrate, as indicated by the RHEED intensity recovery right after the interruption (Fig. 2a). This preservation of the step-and-terrace structure is especially critical for SrRuO3, because it has been otherwise reported to adversely affect the transport properties20. A ∼60 nm-thick SrTiO3 emitter was consecutively grown through a rectangular template mask in 1 mTorr O2. The substrate temperature was 700 °C during the entire growth. The SrRuO3/SrTiO3 (001) heterostructure was fabricated under the same growth conditions. The SrTiO3/SrRuO3/Nb:SrTiO3 (001) trilayer was then Ar-ion etched into rectangular shapes, and annealed in 760 Torr O2 at 350 °C for 6 h to fill oxygen vacancies generated by Ar-ion etching. Rectangular Au and Al electrodes were deposited using e-beam evaporation on the base and emitter, respectively. Indium was ultrasonically soldered onto the collector. These electrodes form Ohmic contacts to each layer.

Perovskite one-dimensional electrical edge contact

∼30 nm-thick Nb:SrTiO3 (0.05 wt% Nb dopant concentration)/monolayer SrRuO3/Nb:SrTiO3 (001) heteroepitaxial trilayer was grown using the same substrates and growth conditions as noted above (the emitter was grown without the use of a template mask). The key step is the growth of a water-soluble and growth-compatible Sr3Al2O6 hard mask layer on the trilayer. The Sr3Al2O6 hard mask layer bypasses aggressive lift-off processes and also serves as a mask during Ar-ion etching and perovskite edge contact regrowth processes involving high growth temperatures and oxidizing conditions. A ∼180 nm-thick Sr3Al2O6 hard mask layer30 was grown in lithographically patterned circular shapes in 5 × 10−6 Torr O2 at room temperature, and capped with a ∼60 nm-thick SrTiO3 grown in 1 mTorr O2 at room temperature to enhance its stability in the air. The trilayer covered with the Sr3Al2O6 hard mask layer in circular shapes was Ar-ion etched to expose the edge of the monolayer base and annealed in 760 Torr O2 at 350 °C for 6 h. A ∼30 nm-thick SrRuO3 edge contact was consecutively grown in 100 mTorr O2 at 700 °C. The entire structure was then immersed into room-temperature filtered de-ionized water to dissolve the Sr3Al2O6 hard mask layer. For device isolation, the trilayer was Ar-ion etched into larger circular shapes and annealed in 760 Torr O2 at 350 °C for 6 h. Electrodes were deposited on each layer as noted above.

Characterization

AFM images were acquired in tapping mode. All electrical measurements of the device were performed using a semiconductor parameter analyzer in DC mode at room temperature in ambient conditions. The in-plane transport measurements were conducted in a four-point geometry with Au contacts for SrRuO3 films.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Jariwala, D., Marks, T. J. & Hersam, M. C. Mixed-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 16, 170–181 (2017).

Yang, H. et al. Graphene barristor, a triode device with a gate-controlled Schottky barrier. Science 336, 1140–1143 (2012).

Lee, C.-H. et al. Atomically thin p–n junctions with van der Waals heterointerfaces. Nat. Nanotech. 9, 676–681 (2014).

Sarkar, D. et al. A subthermionic tunnel field-effect transistor with an atomically thin channel. Nature 526, 91–95 (2015).

Mannhart, J. & Schlom, D. G. Oxide interfaces—an opportunity for electronics. Science 327, 1607–1611 (2010).

Hwang, H. Y. et al. Emergent phenomena at oxide interfaces. Nat. Mater. 11, 103–113 (2012).

Vaziri, S. et al. A graphene-based hot electron transistor. Nano Lett. 13, 1435–1439 (2013).

Guo, Z. et al. Long-range hot-carrier transport in hybrid perovskites visualized by ultrafast microscopy. Science 356, 59–62 (2017).

Brongersma, M. L., Halas, N. J. & Nordlander, P. Plasmon-induced hot carrier science and technology. Nat. Nanotech. 10, 25–34 (2015).

Smoliner, J., Rakoczy, D. & Kast, M. Hot electron spectroscopy and microscopy. Rep. Prog. Phys. 67, 1863–1914 (2004).

Sze, S. M., Crowell, C. R., Carey, G. P. & LaBate, E. E. Hot-electron transport in semiconductor–metal–semiconductor structures. J. Appl. Phys. 37, 2690–2695 (1966).

Bozler, C. O. & Alley, G. D. Fabrication and numerical simulation of the permeable base transistor. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices ED-27, 1128–1141 (1980).

Yajima, T., Hikita, Y. & Hwang, H. Y. A heteroepitaxial perovskite metal-base transistor. Nat. Mater. 10, 198–201 (2011).

Hikita, Y., Kozuka, Y., Susaki, T., Takagi, H. & Hwang, H. Y. Characterization of the Schottky barrier in SrRuO3/Nb:SrTiO3 junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 143507 (2007).

Ohtomo, A. & Hwang, H. Y. A high-mobility electron gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface. Nature 427, 423–426 (2004).

Roy, S., Autieri, C., Sanyal, B. & Banerjee, T. Interface control of electronic transport across the magnetic phase transition in SrRuO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface. Sci. Rep. 5, 15747 (2015).

Toyota, D. et al. Thickness-dependent electronic structure of ultrathin SrRuO3 films studied by in situ photoemission spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 162508 (2005).

Xia, J., Siemons, W., Koster, G., Beasley, M. R. & Kapitulnik, A. Critical thickness for itinerant ferromagnetism in ultrathin films of SrRuO3. Phys. Rev. B 79, 140407(R) (2009).

Chang, Y. J. et al. Fundamental thickness limit of itinerant ferromagnetic SrRuO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 057201 (2009).

Shen, X. et al. Thickness-dependent metal–insulator transition in epitaxial SrRuO3 ultrathin films. J. Appl. Phys. 117, 015307 (2015).

Allen, P. B. et al. Transport properties, thermodynamic properties, and electronic structure of SrRuO3. Phys. Rev. B 53, 4393–4398 (1996).

Hasegawa, S. et al. Direct measurement of surface-state conductance by microscopic four-point probe method. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 8379–8392 (2002).

Klein, L. et al. Anomalous spin scattering effects in the badly metallic itinerant ferromagnet SrRuO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 2774–2777 (1996).

Deng, X. et al. How bad metals turn good: spectroscopic signatures of resilient quasiparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 086401 (2013).

Campillo, I., Pitarke, J. M., Rubio, A., Zarate, E. & Echenique, P. M. Inelastic lifetimes of hot electrons in real metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 2230–2233 (1999).

Ruotolo, A., Lam, C. Y., Cheng, W. F., Wong, K. H. & Leung, C. W. High-quality all-oxide Schottky junctions fabricated on heavily doped Nb:SrTiO3 substrates. Phys. Rev. B 76, 075122 (2007).

Nakamura, M., Sawa, A., Fujioka, J., Kawasaki, M. & Tokura, Y. Interface band profiles of Mott-insulator/Nb:SrTiO3 heterojunctions as investigated by optical spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 82, 201101(R) (2010).

Wang, L. et al. One-dimensional electrical contact to a two-dimensional material. Science 342, 614–617 (2013).

Lu, D. et al. Synthesis of freestanding single-crystal perovskite films and heterostructures by etching of sacrificial water-soluble layers. Nat. Mater. 15, 1255–1260 (2016).

Zhang, P., Lau, Y. Y. & Gilgenbach, R. M. Thin film contact resistance with dissimilar materials. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 124910 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering, under Contract no. DE-AC02-76SF00515. Work on the one-dimensional electrical edge contact was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative through Grant GBMF4415.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S.Y.K. performed the device fabrication, measurements, and data analysis. Y.H., T.Y., and H.Y.H. assisted with the planning, measurements, and analysis of the study. B.S.Y.K. wrote the manuscript, with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, B.S.Y., Hikita, Y., Yajima, T. et al. Heteroepitaxial vertical perovskite hot-electron transistors down to the monolayer limit. Nat Commun 10, 5312 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13290-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13290-3

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.