Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the accuracy and quality of the videos published on YouTube on the subject of disorder of sexual development. The search was performed by using term ‘disorder of sexual development’, ‘differences in sex development’, ‘variations in sex development’ and ‘intersex’ on YouTube. Videos in languages other than English and whose sound or image quality was poor were excluded from the study. The videos were evaluated in terms of source, content, intended audience, commercial bias, and accuracy of information. Video features were recorded. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) criteria, modified DISCERN scale and Global Quality Score (GQS) were used for quality evaluation. A total of 150 videos were evaluated. The source of 30% of the videos was medical education sites, the content of 43.3% was general information and the target audience of 40.6% was patients/society. Accuracy of information rate was 90% and commercial bias rate was 7.3%. The median JAMA, GQS and Modified DISCERN score were 1 (IQR value:2, range:0–2), 3 (IQR value:2, range:2–4) and 3 (IQR value:2, range:1–3) respectively. These scores were correlated with each other (rho = 0.834–0.909 p < 0.001). Scores of the videos whose source was academic journal/university were higher compared to other videos (p < 0.001). The median duration of the videos with good quality was longer (p < 0.001). A negative correlation was found between all scoring systems and number of views/likes/comments, view/comment per day and days since upload date (rho = −0.332, rho = −0.273, rho = −0.382, rho = −0.249, rho = −0.323 rho = −0.285 respectively; p < 0.05). YouTube is a good platform to learn about disorder of sexual development, but the quality may vary depending on the video source.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Disorder of sexual development (DSD) is a clinical condition in which there is a disorder in the anatomical structure of the chromosome, gonad or genitals due to some problems during fetal gender development [1]. The prevalence of this disease is approximately 1:1000 [2]. A multidisciplinary approach is required for newborns with DSD. Since it is a complex disease that needs to be treated in experienced centers with neonatology, pediatric urology, pediatric endocrinology and child psychology specialists, it is necessary to obtain information from quality sources [3]. Today, children and parents with pediatric urological disorders are able to get more detailed information about the disease, treatment methods and outcomes via the Internet [4]. YouTube is the most common social platform in internet but it is a fact that it does not cover the whole internet or all social media [5]. There are many websites and social media platforms that provide information about health. Posts made for this purpose are mostly in the form of videos. These videos are frequently uploaded to YouTube due to accessibility and free sharing [5]. Studies have determined that although some of the medical videos shared on YouTube contain accurate information, there are also videos that contain biased and false information and also has been shown that the information provided has overall low quality [6,7,8]. In the literature, there are many studies analyzing YouTube videos on various medical topics. However, there has been no study conducted on the topic of DSD. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the accuracy and quality of the videos published on YouTube about DSD.

Materials and methods

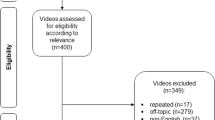

In the present study, YouTube videos were scanned (www.youtube.com) on 30/06/2022 with ‘DSD’, ‘differences in sex development’, ‘variations in sex development’ and ‘intersex’ as the search input. YouTube has its own classification system for video relevance, but they classify it according to video’s title, comments and some keywords. To prevent the YouTube algorithm from producing different results based on user interactions, the search and watch history have been cleared. Videos were not analyzed as animated or non-animated. It was believed that the video style would not impact the study’s outcome, and examining them based on the specified criteria would provide accurate results. The videos were examined separately by two authors. The researchers who examined and scored the videos were both urologists. Any inconsistencies between the authors were resolved through reassessment and consensus. The authors accessed YouTube through Turkey and the videos were examined with the incognito mode turned off. Only videos with English content were included in the study. Videos in languages other than English and videos with poor sound or image quality were excluded from the study. After searching on YouTube, all videos were reviewed. There were 150 videos that met the inclusion criteria for the research.

The videos were classified according to their source: academic journal/university, medical education websites, commercial/industry, patient, hospital/clinic/doctor. All the videos were also evaluated according to the content in information symptoms and diagnosis options, documentary, surgical procedure, lecture, parent/patient experience. The intended audiences of the videos were also determined as patients/society, publicity, medical students and medical practitioners. The target audience was determined subjectively by the researchers based on the video content, the social media account sharing the video, and the video comments. The accuracy of the information and whether there was commercial bias in the videos were determined. Video features were also examined and duration (second), days since upload date, number of views/likes/comments, view par day and comment per day were recorded.

Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) criteria, modified DISCERN scale and Global Quality Score (GQS) were used when evaluating the videos in terms of quality. The JAMA scoring system is used to evaluate the quality of health-related internet posts. Evaluation is made with a total of four parameters. These are authorship, bibliography, patent right, and timeliness. Each parameter is given 0 or 1 point and a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 4 points can be obtained [9]. GQS evaluates the flow, quality and usefulness of the video. A minimum of 1 and a maximum of 5 points can be obtained from GQS. According to these criteria, a score of 1–2 points indicates low quality, a score of 3 points indicates moderate quality, and a score of 4–5 points indicates high quality [10]. Videos with a score of 1 have bad flow and are not useful. Videos with a score of 2 are generally poor and contain limited information. Videos with a score of 3 have moderate quality and some of the important information is adequately discussed. Videos with a score of 4 have good quality, good flow, and useful information. Videos with a score of 5 are top quality videos with excellent quality and flow. The original version of the DISCERN scale consists of 15 items. The short version, the modified DISCERN scale, consists of 5 items [11]. Depending on meeting the criteria, a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 5 points can be obtained. According to these criteria, posts with a score below 3 points are of bad quality and should not be used. Those with a score of 3 points are moderate quality, and those with a score of 4 or 5 points are high quality and useful posts.

Statistical analysis

Data coding and statistical analyzes were performed in computer environment using the SPSS 22 software package program (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL). The conformity of the variables to normal distribution was examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate the difference between means and medians. In cases where more than two variables were compared, Bonferroni correction was used to determine which variable caused the difference. Correlation between variables was analyzed with Spearman’s test. A p value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

A total of 150 videos were evaluated. While the sources of 45 (30%) of the videos were medical education websites, the content of 65 (43.3%) was about general information symptoms and diagnosis options. The target audience of 61 (40.6%) videos was patients/society. The median number of views was 1601 (IQR value:20809, range:341–21150), and the median duration was 901 s (IQR value:1882, range:379–2261). The median JAMA score of the videos was 1 (IQR value:2, range:0–2), median GQS score was 3 (IQR value:2, range:2–4), and median Modified DISCERN score was 3 (IQR value:2, range:1–3). Features and quality scores of the videos are shown in Table 1.

Videos were grouped according to sources, and it was found that the quality scores were significantly different from each other (p < 0.001). According to the Bonferroni correction result, the JAMA, GQS and modified DISCERN scores of the videos whose source was academic journal/university were significantly higher compared to other videos (p < 0.001). In addition, the JAMA, GQS and modified DISCERN scores of the videos whose sources were patient, commercial/industry and hospital/clinic/doctor were significantly lower compared to videos whose source was academic journal/university and medical education websites (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

When classified according to the GQS score, the quality level was low in 40.6%, intermediate in 22.6%, and good in 36.7% of the videos. According to this classification, none of the videos whose sources were commercial/industry and patient were of good quality. 96.4% of the videos whose source was academic journal/university were of good quality. According to this classification, the median duration of the videos with good quality was longer compared to videos with low and intermediate quality (p < 0.001). The number of views, number of likes, number of comments, view per day, comment per day and days since upload date were higher in videos with low quality compared to videos with intermediate and good quality (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Spearman’s test showed that JAMA, GQS and modified DISCERN scores were correlated with each other (rho = 0.834–0.909, p < 0.001). In addition, a positive correlation was found between all scoring systems and duration (rho = 0.447, p < 0.001). Furthermore, a negative correlation was found between all scoring systems and number of views, number of likes, number of comments, view per day, comment per day, and days since upload date (rho = −0.332, rho = −0.273, rho = −0.382, rho = −0.249, rho = −0.323 rho = −0.285 respectively; p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

In recent years, the use of online videos for patients to receive information on medical issues and for medical education of healthcare professionals or students has been increasing [12]. The reliability of video content cannot be ensured because YouTube is an open access platform where anyone can upload a video, and these videos are not subject to any expert or peer review [9]. The main findings of our study, believed to be the first examination of YouTube video content related to DSD, are that videos from academic journals/universities as sources and videos with longer median duration are of higher quality compared to others.

The source of YouTube videos with medical information is an important parameter for quality and reliability [13]. When the videos about pediatric urology are examined, it is seen that the videos published by health professionals are at the forefront. In a study examining Youtube videos about robotic pyeloplasty surgery, it was seen that the most common sources were physician (52%) and academic (18%) [14]. The most common source of videos about vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) was clinician (43.2%), while videos about testicular torsion were primarily uploaded by education and training websites (30%) and physicians (23%) [15, 16]. Consistent with the existing literature, this study found that videos related to DSD were mostly published by healthcare professionals, and the most common source was medical education websites (30%). This was likely due to the large number of videos for the education of medical students and doctors, since DSD is a complex and difficult subject to learn.

In the literature, the content of pediatric urology videos varies. While general information videos such as symptoms and diagnosis options are at the forefront for VUR and testicular torsion, it has been determined that surgical procedure is the most common video content for hypospadias and robotic pyeloplasty [14,15,16,17]. In our study, the most common video content was general information, symptoms, and diagnosis options (43.3%), followed by lectures (30.7%).

On the other hand, surgical procedures had the lowest rate (6.7%). This difference in the content of published videos is thought to be due to the diversity of medical topics covered. Most common intended audience was patients/society (40.6%), followed by medical students (32%). These data demonstrate the importance of DSD videos not only for healthcare professionals and medical students, but also for patients. Although the intended audience varied, the rate of accuracy of the information was 90%. While not all videos were of high quality, the rate of misinformation was very low. The commercial bias rate was 7.3%, and the videos with an intended audience of publicity constituted only 4.7% of the videos. This showed that a small portion of the videos published on DSD were intended for financial gain.

Ample research has been conducted to measure the quality and reliability of the videos published on the Internet, and different scoring systems have been used to examine videos [14, 17]. In the present study, videos were evaluated with JAMA, GQS and modified DISCERN scores. The average JAMA score of the videos was calculated as 1, average GQS score was 3, and average modified DISCERN score was 3. Correlation analysis revealed that JAMA, GQS and modified DISCERN scores were correlated with each other (p < 0.001). Studies in the literature found that the quality and reliability of videos increased when videos were published by academicians or physicians and the modified DISCERN, JAMA and GQS scores of these videos were significantly higher compared to other videos [7, 14]. In a study examining VUR videos, it was determined that the average JAMA, GQS and modified DISCERN scores were 3. In the same study, it was seen that the JAMA, GQS and modified DISCERN scores of the videos published by hospital, clinician, practice were higher compared to videos published by industry/ advertisements/for profit organizations, individual users and patients [15]. In another study on pediatric urology, the average JAMA and GQS score of the videos were calculated as 2.1, and it was determined that the videos published by academic/physicians had higher scores compared to other videos [14]. On the other hand, there are also studies in the literature that do not report any statistical relationship between video source and these scores [18]. In the present study, the quality scores of the videos separated according to their sources were significantly different from each other (p < 0.001). The JAMA, GQS and modified DISCERN scores of the videos published by academic journal/university were significantly higher compared to other videos (p < 0.05). JAMA, GQS and modified DISCERN scores of videos published by patient, commercial/industry and hospital/clinic/doctor were significantly lower compared to videos published by academic journal/university and medical education (p < 0.05). According to the GQS score, 36.7% of the videos were of good, 22.6% of them were of intermediate, and 40.6% of them were of low quality. There are studies in the literature reporting that the GQS score is higher in academic videos [19]. In the present study, it was determined that 96.4% of the videos published by academic journal/university were of good quality, while none of the videos published by commercial/industry and patient were of good quality.

As the length of the video increases, more details can be given on the topics covered, which in turn can manage to an increase in video quality and reliability [13, 20]. In the present study, it was observed that the median duration of good videos was longer compared to low and intermediate quality videos (p < 0.01). In addition, a positive correlation was found between all scoring systems and video duration (p < 0.001). Number of views, number of likes, number of comments, view per day, comments per day and days since upload date were higher in low quality videos compared to intermediate and good quality videos (p < 0.05). A negative correlation was found between these parameters and all scoring systems (p < 0.05). Since high quality videos are generally longer, viewers may be distracted or lose interest in the video, which can lead to lower viewing rates. It is therefore likely that low quality videos reach higher interaction rates than high quality videos. However, it should not be overlooked that dislike rates may be high in videos with a high number of views or comments, and that although low quality videos receive higher views, the viewers can still realize that the video contains false information [19]. On the other hand, there were videos with views exceeding 5 million, and the average number of views was 1601. The high view counts emphasize the importance of examining the quality and reliability of these videos.

Limitations

The dislike numbers of videos are hidden by YouTube, therefore the dislike/like ratios and video power index could not be examined in the present study, which is a limitation. Another limitation is related to the keywords. Different keywords can be used to search for the same topic on YouTube. It is considered that this situation may affect the results of our study. Additionally, both researchers were located in Turkey. Due to YouTube rules in showing videos related to geographical location, the location itself could be considered a bias. The subjective analysis of videos by the researchers has also been considered a limitation of our study.

Conclusion

YouTube has recently become an important source of information for patients, medical students and doctors on medical issues. However, since the content is published without any expert or referee review, there is risk of misinformation along with reliability problems due to commercial concerns. Therefore, it is very important to evaluate the quality and reliability of medical videos posted on social media or websites.

Many videos about DSD have been posted on YouTube to date, and although they have different sources and vary in quality and content, YouTube is generally a good platform for information. Videos published by academic journals/universities provide evidence-based, more detailed and accurate information. For this reason, when choosing videos on this subject, attention should be paid to the source.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Laino L, Majore S, Preziosi N, Grammatico B, De Bernardo C, Scommegna S, et al. Disorders of sex development: a genetic study of patients in a multidisciplinary clinic. Endocr Connect. 2014;3:180–92.

Monlleó IL, Zanotti SV, Araújo BPBD, Cavalcante Júnior EF, Pereira PD, Barros PMD, et al. Prevalence of genital abnormalities in neonates. J de Pediatr. 2012;88:489–95.

Crerand C, Kapa H, Litteral J, Nahata L, Combs B, Indyk J, et al. Parent perceptions of psychosocial care for children with differences of sex development. J Pediatr Urol. 2019;15:522.e1–e8.

Fast AM, Deibert CM, Hruby GW, Glassberg KI. Evaluating the quality of Internet health resources in pediatric urology. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9:151–6.

Farnan JM, Paro JA, Higa J, Edelson J, Arora VM. The YouTube generation: implications for medical professionalism. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51:517–24.

Ozsoy‐Unubol T, Alanbay‐Yagci E. YouTube as a source of information on fibromyalgia. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24:197–202.

Selvi I, Baydilli N, Akinsal EC. Can YouTube English videos be recommended as an accurate source for learning about testicular self-examination? Urology. 2020;145:181–9.

Cilio S, Collà Ruvolo C, Turco C, Creta M, Capece M, La Rocca R, et al. Analysis of quality information provided by “Dr. YouTubeTM” on phimosis. Int J Impot Res. 2023;35:398–403.

Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: Caveant lector et viewor—Let the reader and viewer beware. Jama. 1997;277:1244–5.

Bernard A, Langille M, Hughes S, Rose C, Leddin D, Van Zanten SV. A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the World Wide Web. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol| ACG. 2007;102:2070–7.

Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:105–11.

Canvasser NE, Ramo C, Morgan TM, Zheng K, Hollenbeck BK, Ghani KR. The use of social media in endourology: an analysis of the 2013 World Congress of Endourology meeting. J Endourol. 2015;29:615–20.

Duran MB, Kizilkan Y. Quality analysis of testicular cancer videos on YouTube. Andrologia. 2021;53:e14118.

Adorisio O, Silveri M, Torino G. Evaluation of educational value of YouTube videos addressing robotic pyeloplasty in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2021;17:390.e1–e4.

Toksoz A, Duran MB. Analysis of videos about vesicoureteral reflux on YouTube. J Pediatr Urol. 2021;17:858.e1–e6.

Bai G, Pan X, Zhao T, Chen X, Liu G, Fu W. Quality assessment of YouTube Videos as an information source for testicular torsion. Front Public Health. 2022;10:905609.

Salama A, Panoch J, Bandali E, Carroll A, Wiehe S, Downs S, et al. Consulting “Dr. YouTube”: an objective evaluation of hypospadias videos on a popular video-sharing website. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16:70.e1–e9.

Culha Y, Seyhan Ak E, Merder E, Ariman A, Culha MG. Analysis of the YouTube videos on pelvic floor muscle exercise training in terms of their reliability and quality. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021;53:1–6.

Onder ME, Zengin O. YouTube as a source of information on gout: a quality analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:1321–8.

Gas S, Zincir OO, Bozkurt AP. Are YouTube videos useful for patients interested in botulinum toxin for bruxism? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77:1776–83.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ST and MVK: data collection and analysis; ST: paper writing; MVK: supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Toksoz, S., Kayra, M.V. Quality of information in Youtube videos on disorder of sexual development. Int J Impot Res (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-023-00800-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-023-00800-7