Abstract

Purpose

More than a decade after the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) was passed, there is a paucity of research on the general public’s awareness of GINA. This study’s objective was to assess knowledge of GINA and concerns of genetic discrimination.

Methods

A quota-based sample of US adults (N = 421) was recruited via Qualtrics Research Services to complete an online survey.

Results

Overall, participants had a mean age of 43.1 (SD = 13.9), 51.8% identified as female, 63.1% identified as non-Hispanic White, and 38.4% had ≥4-year college degree. Respondents reported relatively low subjective knowledge of GINA (M = 3.10, SD = 1.98; 7-point Likert scale). Among respondents reporting high subjective knowledge of GINA (16.2%), 92.6% incorrectly reported or did not know that GINA does not covers life, long-term care, and disability insurance, and this number was 82.4% for auto or property insurance. Respondents were relatively likely to decline genetic testing due to concerns about results being used to determine eligibility for employment (M = 4.68, SD = 1.89) or health insurance (M = 4.94, SD = 1.73). There were few consistent demographic associations with either subjective or objective knowledge of GINA.

Conclusion

This study highlights continued public concern about genetic discrimination and a lack of awareness and understanding of GINA and its scope of protections.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The Human Genome Project was intended to promote health through a greater understanding of genetics and increased access to genetic testing. However, there was public concern that results could be used to discriminate. Anecdotal evidence suggested that some discrimination by health insurers and employers was occurring and that some individuals were avoiding genetic testing and research out of fear of potential negative consequences [1]. This was supported by empirical studies examining decision factors related to refusing genetic testing that indicated individuals were worried about genetic discrimination [2,3,4] or confidentiality [5, 6]. Studies highlighted concerns about the use of genetic information across employment and different insurance types [3, 7].

In response to those concerns, Congress passed the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) in 2008 [8]. The law recognized the importance and benefits of genetic testing and prohibited genetic discrimination in health insurance and employment [8]. Specifically, health insurers may not underwrite or set premiums based on genetic information [9]. For employers, the law prevents entities from making decisions, such as hiring or pay, based on genetic information [9]. GINA also limits the ability of covered health insurers and employers to collect genetic information, which includes genetic test results and family medical history—although collection of this information is allowable in some situations where sharing of medical information is common and necessary, such as for insurance billing or family medical leave requests.

There are several important exceptions to GINA’s scope. First, in employment, the act does not apply to employers with fewer than 15 employees. Second, GINA applies to health insurance, but long-term care (LTC), life, and disability insurances are not included [10]. Finally, GINA does not apply to the military and associated health insurances (e.g., Tricare), although other laws and policy provide some relevant protections [11].

GINA defines genetic information broadly to include family members’ medical history because this could be a proxy for one’s own genetic predispositions; however, it draws a distinction between predictive information, which GINA protects, and manifested conditions (having symptoms), which GINA does not protect. In contrast, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) does address use of manifested conditions in health insurance. Thus, GINA and the ACA work together with GINA preventing health insurers from considering predictive genetic information and the ACA preventing them from taking into account pre-existing conditions, including genetic information and manifested conditions [10]. Relatedly, the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) governs the privacy of health information in the health-care setting. However, the law does little to fill in the gaps of GINA since individuals must often sign a waiver of HIPAA privacy rights when applying for insurances other than health.

Some studies have concluded that GINA may not be realizing its full intent due to the public’s lack of knowledge about the law [12]. In the decade following GINA’s passage, the few quantitative studies evaluating different groups’ awareness of GINA show a lack of knowledge of the act and its scope among health-care providers [13,14,15], patients [12, 16, 17], and subsets of the general population [18, 19] (Table 1), with the latter having the lowest rates of knowledge of GINA. When surveys asked about specific provisions of GINA, few respondents in both provider and patient surveys could correctly identify the protections [17, 18]. Perhaps because of this low knowledge of GINA, fear of genetic discrimination continues to serve as a barrier for many for utilizing genetic testing [17, 20, 21] (Table 1). Health-care providers also report concerns of genetic discrimination against patients [13, 22,23,24,25].

Previous studies on fear of genetic discrimination and knowledge of GINA have generally been limited because they have focused on specific patient or provider populations. A handful of studies have surveyed the general public but were limited either by not asking questions about objective GINA knowledge [19] or by not measuring or fully reporting sample demographics [18, 19, 26]. Thirteen years after GINA, this study was designed to assess current knowledge and understanding of GINA and concerns of genetic discrimination in the general population. We sought to include diverse respondents across age, gender, race, and education to assess whether both subjective and objective knowledge of the law, and concerns about genetic discrimination, varied across subpopulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Respondents and procedures

Quota-based sampling was used to recruit survey respondents through Qualtrics Research Services (n = 421) between 2 and 8 April 2020. A sample size of 406 is needed to detect a mean difference of 0.50 between two groups with 80% power and alpha = 0.05. Inclusion criteria were US residence and aged ≥18 years. Quotas were created for gender, age, race, ethnicity, educational attainment, and total household income to ensure that respondent characteristics mirrored population rates. Of 586 respondents, 96 did not reach the end of the survey and 69 were excluded for providing low quality responses, resulting in a final sample size of 421 respondents (71.8% completion rate). Respondents were compensated based on their panel agreement with Qualtrics.

Measures

The survey included validated survey measures identified from the literature review, as well as novel questions developed by our study team. It had 58 questions, including multiple choice and Likert scale questions and subquestions (Supplementary Materials).

Demographics

Demographics included gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, and income in addition to demographics we hypothesized may impact knowledge of GINA or concern of genetic discrimination (Supplementary Materials). Notably, in addition to the screening demographics, political identity (7-point Likert scale with scale anchors of extremely liberal [1] and extremely conservative [7]) and religiosity (7-point Likert scale with scale anchors of not at all religious [1] to very religious [7]) were included since greater political conservatism and religiosity are associated with increased concern about personal liberty, which we hypothesized could be linked to concern about how genetic test results are used [27].

Knowledge of GINA

Several questions assessed knowledge of GINA. After asking respondents broadly if they are aware of any laws that protect against the use of genetic information (yes/no/I don’t know), we asked about familiarity with specific laws (ACA, GINA, HIPAA) to measure respondents’ subjective knowledge (7-point Likert scale with scale anchors of not at all familiar [1] and extremely familiar [7]). Respondents were also asked about whether GINA provides protection in health insurance, employment, life insurance, LTC insurance, disability insurance, auto insurance, and property insurance. They could answer with no, yes, or I don’t know to each of those categories. The survey did not display correct answers after responses were submitted. Additionally, a measure of genetics literacy (nine true/false items) was included as a covariate in multiple regression [28].

Fear of genetic discrimination

We also included several questions to assess respondents’ concerns about discrimination. We first measured perceived likelihood of privacy violations in multiple areas to help contextualize responses regarding concerns about use of genetic information relative to other forms of personal information. Three items assessing concern over the privacy of their financial, medical, and genetic information were adapted from Dorsey et al. [17]. We also developed two items similar to the Dorsey items measuring concern over privacy of their information in general and family medical history (7-point Likert scale with scale anchors of not at all concerned [1] and very concerned [7]).

Fear of genetic discrimination was assessed by first asking if respondents believed it was important to have laws that prevent genetic test results from being used by entities outside of the medical field. Respondents answered using a 7-point Likert scale with scale anchors of not at all important (1) and extremely important (7). Respondents were also asked if they believed it was likely their genetic information could be used to determine employment status and insurance coverage (health, life, disability, LTC). Finally, they were asked the likelihood that they would decline testing based on concerns of genetic test results being used to make decisions about employment or each of the four insurance types (7-point Likert scales were also used with scale anchors of not at all likely [1] and very likely (7]).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all demographics and measures of interest. One-sample t-tests, paired-sample t-tests, and chi-squared analyses were used to test for group differences and multiple linear regression analyses were used to identify significant associations with our key measures of interest. All analyses were conducted using Stata 14.2 (College Station, TX).

Recoded variables

To identify respondents’ subjective knowledge of GINA, answers to the familiarity of GINA question were recoded with Likert scores of 1–2 (1: low subjective knowledge), 3–5 (2: moderate subjective), and 6–7 (3: high subjective knowledge).

Respondents’ objective knowledge of GINA was coded as 1 if they correctly recognized that GINA covers health insurance and employment but not life, LTC, disability, auto, or property insurance and 0 if indicating any incorrect coverage or that they did not know the protections. Separate measures were created to assess the accuracy of whether GINA covers employment and health insurance (2 = correctly indicating that GINA covers both, 1 = correctly indicating one of the two, and 0 = not indicating either or that they didn’t know); life, LTC, and disability insurances (3 = correctly indicating that GINA does not cover all three, 2 = incorrectly indicating that GINA covers one of these, 1 = incorrectly indicating that GINA covers two of these, and 0 = incorrectly indicating that GINA covers all three or that they did not know); or auto and property insurance (2 = correctly indicating that GINA does not cover both, 1 = correctly indicating GINA covers one of these, and 0 = incorrectly indicating that GINA covers both or that they did not know).

RESULTS

Demographics

Respondents had a mean (M) age of 43.1 years (standard deviation [SD] = 13.9), with 51.8% identifying as female, 36.6% as non-White, and 38.4% had a four-year college degree or more (Table 2). Approximately 40% of respondents reported a household income below $50,000 (Table 2). Respondents had a mean political ideology of 4.17 (SD = 1.60) and mean religiosity of 3.97 (SD = 2.06); both average responses were close to the midpoints of the scales. When asked to rate their overall health, 23.7% of respondents indicated they had poor or fair health, 39.5% good health, and 36.8% very good or excellent health. Other personal characteristics (e.g., occupation and history of genetic testing) were collected but were excluded from analyses due to insufficient numbers of respondents in these groups to achieve satisfactory statistical power (Supplementary Materials).

Knowledge of GINA

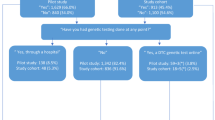

Overall, individuals reported higher familiarity with HIPAA (M = 4.19, SD = 1.97), t(420) = −10.44, p < 0.001, and the ACA (M = 4.75, SD = 1.53), t(420) = −15.55, p < 0.001, than with GINA (M = 3.10, SD = 1.98). Of the 421 respondents, 195 (46.3%) reported low subjective knowledge of GINA, 158 (37.5%) reported moderate subjective knowledge, and 68 (16.2%) reported high subjective knowledge. When asked about specific provisions of GINA, the majority of respondents failed to correctly identify the law’s protections (Fig. 1). Indeed the majority of respondents chose “I don’t know” for employment (54.2%) and all types of insurance—health (59.6%), life (61.1%), LTC (64.1%), disability (62.7%), auto (55.1%), and property (54.4%). The distribution of correct responses on the genetic literacy measures were fewer than 4 (19%), 5–6 (42%), and 7 or more (39%) (Table 2).

Of those who reported high subjective knowledge of GINA, 54.4% correctly identified that the law covers both health and employment, χ2(4,421) = 76.6, p < 0.001. Over half of respondents with high subjective knowledge (60.3%) incorrectly reported or did not know that GINA covers life, LTC, and disability insurance while only 7.4% correctly responded that the law does not cover any of these areas, χ2(6,421)=43.8, p < 0.001. Also, of this group, over half (54.4%) incorrectly believed or did not know that GINA covers auto and property while only 17.6% correctly reported that the law does not cover either of these areas, χ2(4,421)=36.5, p < 0.001.

The multivariable regression analysis for subjective knowledge of GINA revealed few significant associations. Older age was associated with lower subjective knowledge of GINA (regression coefficient [B] = −0.05, p < 0.001), while increased religiosity (B = 0.19, p < 0.001) and better self-reported health (B = 0.22, p = 0.04) were associated with increased subjective knowledge of GINA (Table 3). Subjective and objective knowledge of genetics had divergent associations with the subjective GINA knowledge: greater subjective genetic knowledge was associated with greater subjective GINA knowledge (B = 0.33, p = 0.001), while greater objective genetic knowledge was associated with less subjective GINA knowledge (B = −2.67 p < 0.001). Subjective GINA knowledge was the only significant association with any of the forms of objective GINA knowledge measures. Greater subjective GINA knowledge was associated with greater objective knowledge of GINA in the areas of health and employment (B = 0.65, p < 0.001), and the areas of life, LTC, and disability insurance (B = 0.27, p = 0.013).

Fear of genetic discrimination

Respondents were fairly concerned about the privacy of their information in general (M = 5.48, SD = 1.46) and their financial (M = 5.71, SD = 1.46), medical (M = 5.35, SD = 1.52), genetic (M = 4.91, SD = 1.66), and family history (M = 5.04, SD = 1.67) information specifically. Paired t-test analysis showed that respondents were less concerned about the privacy of their genetic information than the privacy of their general personal information, t(420) = −8.48, p < 0.001, financial information, t(420) = −10.68, p < 0.001, medical information, t(420) = −6.94, p < 0.001, or family medical history, t(420) = −2.23, p = 0.013. Although respondents were less concerned about genetic privacy than other forms of privacy, when asked how important they thought it was to have a law that prevented genetic test results from being used outside of the medical field, 80% were above scale midpoint (Fig. 2). No demographic characteristics were significantly associated with concern about the privacy of their genetic information.

Overall, respondents believed that genetic information would be used to determine health (M = 4.91, SD = 1.74), disability (M = 5.00, SD = 1.66), LTC (M = 5.02, SD = 1.61), and life (M = 5.11, SD = 1.67) insurance coverage (Fig. 2), but not employment (M = 4.06, SD = 1.86). Survey respondents were more likely to think genetic information would be used for health insurance coverage than employment decisions, t(420) = 9.56, p < 0.001. Respondents were also less likely to think that genetic information would be used to determine health insurance coverage than life insurance coverage, t(420) = −2.90, p = 0.002. Higher self-reported health (B = 0.28, p = 0.007), being more politically conservative (B = 0.13, p = 0.048), and greater subjective knowledge (B = 0.23, p < 0.001) were associated with an increased belief that genetic information would be used in health insurance determinations (Table 3).

In addition, many respondents indicated that they would be likely to decline genetic testing due to concerns about how the test results would be used in employment (M = 4.68, SD = 1.89) and for health (M = 4.94, SD = 1.73), life (M = 4.86, SD = 1.78), LTC (M = 4.90, SD = 1.74), and disability (M = 4.78, SD = 1.79) insurances (Fig. 2). Respondents were more likely to decline hypothetical genetic testing based on concerns about the test results impacting health insurance coverage compared to the results impacting employment, t(420) = 3.40, p < 0.001 or disability insurance coverage, t(420) = 2.24, p = 0.013. Identifying as male (B = 0.46, p = 0.044) and increased belief that health insurers would use genetic information in determining health insurance coverage (B = 0.31, p < 0.001) were associated with increased intentions to decline genetic testing based on concerns about the test results impacting health insurance coverage (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This article reports on a general population-based study of the knowledge of GINA and fear of discrimination more than a decade after the law’s implementation. Below we discuss key aspects of our main findings regarding knowledge of GINA and fear of genetic discrimination.

Knowledge of GINA

Our primary finding is that knowledge of GINA continues to be low across the general population. The mean subjective knowledge with GINA was below the scale midpoint and only 34% or less of respondents provided a correct response to each objective question. Our results are consistent with earlier studies completed in the months and years following GINA’s passage that found low rates of knowledge of GINA. Additionally, while previous research in this area has generally focused on specific groups, our use of a national sample that was generally representative across race, ethnicity, gender, education, and income highlights the pervasiveness of this lack of knowledge among the US public.

This lack of knowledge of GINA is not readily explained by demographic characteristics. Our multivariable analysis identified few consistent associations with knowledge of GINA, highlighting that GINA knowledge appears to be limited across groups. Interestingly, religiosity, self-reported health, and age were the only demographics we found to be statistically significantly associated with subjective knowledge of GINA.

Survey respondents reported greater familiarity with other health-related laws, such as the ACA and HIPAA, than with GINA. This discrepancy in knowledge of health privacy laws is perhaps not surprising given differences in media coverage and public discussion of the ACA, and even HIPAA, compared to GINA. Future studies should also interrogate how knowledge of GINA compares to understanding of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in the employment context.

Furthermore, over 80% of our respondents reported low or moderate subjective knowledge of GINA. These findings parallel previous GINA studies that found low awareness of GINA ranging from 8.8% awareness [18] to 20% awareness [16, 19]. Additionally, even in studies of patient groups with a genetic condition, knowledge of GINA was still lower than that of other privacy laws (Table 1) [17].

A hypothesis for the lack of continued awareness of GINA in the general population is that it has not often been utilized. In the employment context, GINA has had limited impact [29, 30]. While some employment cases have been brought, the majority of cases have related to employers collecting family medical history rather than discriminating on the basis of an employee’s genetic test result [29, 30]. While individuals can sue employers for violations of GINA, there is no private right of action against insurers, so all the case examples are from employment. Furthermore, in health insurance, the ACA significantly diminished the impact of GINA [10]. While GINA prevents health insurers from using predictive genetic information in underwriting, the ACA prevents them from using all pre-existing conditions, including manifested genetic conditions—thus impacting a greater portion of the general public. This likely helps explain both why the public may have low awareness of GINA and why there is greater knowledge of the ACA than GINA.

An important secondary finding of the survey is that even when respondents reported high subjective knowledge of GINA, they frequently did not have an accurate or complete understanding of the specific provisions of the law. Respondents with high subjective knowledge of GINA believed that the law had broader protections than it actually does. For example, they thought that the law covered life, LTC, disability, and even auto and property insurances. This finding is also supported by past literature with specific populations. For example, one study found that, overall, the majority of individuals affected by Huntington disease failed to correctly identify the law’s protections [17] (Table 1).

Our results raise the possibility that there needs to be both an increase in knowledge of GINA, but also clearer messaging of what the law covers. However, knowledge of both GINA and its specific provisions raises the possibility of a catch 22. GINA was passed in part to minimize fears of genetic discrimination [31]. Raising awareness of the law could potentially help to assuage the continuing fear of genetic discrimination that has occurred since GINA was passed. Yet making individuals aware of both the existence of GINA and the limited scope of its protections may lead to lower rates of testing or participation in research in the absence of expansion of GINA’s protections [32]. For example, our study found that as respondents’ subjective knowledge of GINA increased, the more likely they believed (incorrectly) that the law provided protections in life, LTC, and disability insurance. Other studies found that after being educated about GINA and its specific provisions, some people had fewer concerns, while others had more concerns [21, 26, 33]. Recently Florida passed a law barring life, LTC, and disability insurers from using genetic test results in underwriting [34]. Such an expansion of GINA’s protections provides an opportunity for future research to help understand whether awareness or knowledge of more comprehensive protections alleviates discrimination concerns.

Fear of genetic discrimination

The survey highlights that the general population continues to have concerns about participating in genetic testing given potential privacy and discrimination risks. Perhaps surprisingly, respondents were less concerned about genetic privacy than they were the privacy of other types of information, such as financial, medical, and even family medical history. One potential reason for this may be that most respondents may have never undertaken genetic testing, making any concerns about privacy of genetic information hypothetical, whereas they may have more experience with the other information categories.

Despite this lower concern for genetic privacy, respondents indicated that they were still worried about genetic discrimination, as 80% were above scale midpoint for the question about how important they thought it was to have a law that prevented genetic test results from being used outside of the medical field (Fig. 2). Additionally, respondents believed that it was likely that genetic test results would be used in insurance and, to a lesser extent, employment. Since we did not provide respondents with the correct answers to the objective GINA questions, their reported concerns about genetic discrimination could be based on lack of knowledge or misunderstanding of GINA’s protections. We found those with better self-reported health and with more conservative political identity were significantly more likely to think that genetic information would be used in health insurance determination. We also found that those identifying as male were significantly more likely to decline genetic testing out of concern for this use.

Most notably, a majority of respondents indicated that they would be likely to decline genetic testing due to discrimination fears, with 60% of respondents indicating they would be likely to decline testing out of concern for how the results would be used for employment and insurance coverage determinations (Fig. 2). Thus, simply raising awareness that insurers might find genetic information useful, and that GINA does not protect this information outside of health insurance and employment, could potentially lead to increased fear of discrimination. Similar to the knowledge of GINA results, there were few significant associations with the belief that genetic information would be used in health insurance or with the intentions to decline genetic testing out of concern of such use (Table 3).

This study has several limitations. Sample recruitment occurred through an opt-in panel. Thus, respondents needed an Internet-connected device and may not be as representative as a probability-based sample. Yet, this option allowed for testing in the general population with purposeful sampling across subpopulations and the lack of differences across subgroups suggest that the relative differences between measures would not change dramatically with a probability-based sample. Additionally, we were unable to test other respondent characteristics such as insurance status, history of genetic testing, or personal and family medical history, due to lack of statistical power. However, in subsequent analysis we have been able to study these respondent characteristics by combining data from this survey with another subsequent survey [35]. Briefly, we found that while those who had been offered or taken a genetic test had higher subjective and objective knowledge of GINA than those not offered testing, knowledge of GINA was still incredibly low across all populations. Finally, one limitation of the study is that, when assessing concern of genetic discrimination, we asked about the likelihood of declining hypothetical genetic testing. Responses may be different with a hypothetical scenario than when faced with real-world trade-offs between the benefits and risks of genetic testing; however, studies have found that individuals do decline genetic testing based on discrimination concerns in nonhypothetical scenarios [21].

This study, as with others that have come before it, highlights a continued lack of awareness of GINA, including persistently limited understanding or knowledge of the law’s scope of protections. Currently, the public may only learn about GINA when they seek a genetic test or participate in research and read the informed consent [33, 36]. However, this study suggests the possibility that we may be losing people before they even get to the informed consent stage if they worry about discriminatory use of genetic information and are unaware of, or misunderstand, GINA’s protections. Perhaps a silver lining is that this knowledge gap seems to be across the board, without one population subgroup being particularly advantaged or disadvantaged in their knowledge of GINA. Our results highlight that raising awareness at the time of informed consent has not done enough to move the needle on public knowledge of GINA more than a decade after its passage. Further research is needed to understand the most effective ways of communicating information about the protections of GINA in ways to avoid counterproductive reactions where increased knowledge of GINA can be associated with greater fear of discrimination.

Data availability

The survey instrument is available in the Supplementary Materials and the survey data and Stata syntax is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Change history

27 August 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-021-01305-8

References

Faces of Genetic Discrimination How Genetic Discrimination Affects Real People. Washington, DC: National Partnership for Women & Families on behalf of the Coalition for Genetic Fairness; 2004. http://go.nationalpartnership.org/site/DocServer/FacesofGeneticDiscrimination.pdf.

Hall MA, McEwen JE, Barton JC, Walker AP, Howe EG, Reiss JA, et al. Concerns in a primary care population about genetic discrimination by insurers. Genet Med. 2005;7:311–6.

Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Duteau-Buck C, Guevarra J, Bovbjerg DH, Richmond-Avellaneda C, et al. Psychosocial predictors of BRCA counseling and testing decisions among urban African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1579–85.

Sterling R, Henderson GE, Corbie-Smith G. Public willingness to participate in and public opinions about genetic variation research: a review of the literature. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1971–8.

Peterson EA, Milliron KJ, Lewis KE, Goold SD, Merajver SD. Health insurance and discrimination concerns and BRCA1/2 testing in a clinic population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:79–87.

Sankar P, Wolpe PR, Jones NL, Cho M. How do women decide? Accepting or declining BRCA1/2 testing in a nationwide clinical sample in the United States. Community Genet. 2006;9:78–86.

Armstrong K, Weber B, FitzGerald G, Hershey JC, Pauly MV, Lemaire J, et al. Life insurance and breast cancer risk assessment: Adverse selection, genetic testing decisions, and discrimination. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;120A:359–64.

The Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act. Public Law 110-223. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ233/pdf/PLAW-110publ233.pdf Accessed 8 November 2019.

National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetic discrimination. https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/policy-issues/Genetic-Discrimination. Accessed 5 November 2020.

Prince AE, Roche MI. Genetic information, non-discrimination, and privacy protections in genetic counseling practice. J Genet Couns. 2014;23:891–902.

Baruch S, Hudson K. Civilian and military genetics: nondiscrimination policy in a post-GINA world. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:435–44.

Allain DC, Friedman S, Senter L. Consumer awareness and attitudes about insurance discrimination post enactment of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. Fam Cancer. 2012;11:637–44.

Laedtke AL, O’Neill SM, Rubinstein WS, Vogel KJ. Family physicians’ awareness and knowledge of the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act (GINA). J Genet Couns. 2012;21:345–52.

Wilson Steck MB, Eggert JA, Parker VG, et al. Assessing awareness of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA) among nurse practitioners: a pilot study. Int Arch. Nurs Health Care. 2016;2:1–6.

Pamarti AK. Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) and its affect [sic] on genetic counseling practice: a survey of genetic counselors. Master’s thesis, Brandeis University, 2011.

Cragun D, Weidner A, Kechik J, Pal T. Genetic testing across young Hispanic and non-Hispanic white breast cancer survivors: facilitators, barriers, and awareness of the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2019;23:75–83.

Dorsey ER, Darwin KC, Nichols PE, Kwok JH, Bennet C, Rosenthal LS, et al. Knowledge of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act among individuals affected by Huntington disease. Clin Genet. 2013;84:251–7.

Huang MY, Huston SA, Perri M. Awareness of the US Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008: an online survey. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2013;4:235–8.

Parkman AA, Foland J, Anderson B, Duquette D, Sobotka H, Lynn M, et al. Public awareness of genetic nondiscrimination laws in four states and perceived importance of life insurance protections. J Genet Couns. 2015;24:512–21.

Amendola LM, Robinson JO, Hart R, Biswas S, Lee K, Bernhardt BA, et al. Why patients decline genomic sequencing studies: experiences from the CSER Consortium. J Genet Couns. 2018;27:1220–7.

Robinson JO, Carroll TM, Feuerman LZ, Perry DL, Hoffman-Andrews L, Walsh RC, et al. Respondents and study decliners’ perspectives about the risks of participating in a clinical trial of whole genome sequencing. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2016;11:21–30.

Fusina L. Impact of GINA on physician referrals for genetic testing for cancer predisposition. Master’s thesis, Mount Sinai School of Medicine of New York University, 2009.

Huizenga CR, Lowstuter K, Banks KC, Lagos VI, Vandergon VO, Weitzel JN. Evolving perspectives on genetic discrimination in health insurance among health care providers. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:253–60.

Matloff ET, Bonadies DC, Moyer A, Brierley KL. Changes in specialists’ perspectives on cancer genetic testing, prophylactic surgery and insurance discrimination: then and now. J Genet Couns. 2014;23:164–71.

Matloff ET, Shappell H, Brierley K, Bernhardt BA, McKinnon W, Peshkin BN. What would you do? Specialists’ perspectives on cancer genetic testing, prophylactic surgery, and insurance discrimination. J of Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2484–92.

Green RC, Lautenbach D, McGuire AL. GINA, genetic discrimination, and genomic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:397–9.

Iyer R, Koleva S, Graham J, Ditto P, Haidt J. Understanding libertarian morality: The psychological dispositions of self-identified libertarians. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42366.

Gornick MC, Scherer AM, Sutton EJ, Ryan KA, Exe NL, Li M, et al. Effect of public deliberation on attitudes toward return of secondary results in genomic sequencing. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:122–32.

Suter SM. GINA at 10 years: the battle over ‘genetic information’ continues in court. J Law Biosci. 2018;5:495–526.

Areheart BA, Roberts JL. GINA, big data, and the future of employee privacy. Yale Law J. 2019;128:710–90.

McGuire AL, Majumder MA. Two cheers for GINA? Genome Med. 2009;1:6.1–3.

Wauters A, Hoyweghen IV. Global trends on fears and concerns of genetic discrimination: a systematic literature review. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;61:275–82.

Clayton EW, Halverson CM, Sathe NA, Malin BA. A systematic literature review of individuals’ perspectives on privacy and genetic information in the United States. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204417.

Anderson J, Lewis ACF, Prince AER. The problems with patchwork: state approaches to regulating insurer use of genetic information. DePaul J Health Care Law. 2021;22:1–40.

Prince AER, Uhlmann WR, Suter SM, Scherer AM. Genetic testing and insurance implications: Surveying the US general population about discrimination concerns and knowledge of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). Forthcoming (on file with authors).

Henderson GE, Wolf SM, Kuczynski KJ, Joffe S, Sharp RR, Parsons DW, et al. The challenge of informed consent and return of results in translational genomics: empirical analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics. 2014;42:344–55.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R00HG008819. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank the Iowa Social Science Research Center for their survey support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.L., A.M.S., W.R.U., S.M.S., C.A.H., A.E.R.P. Formal analysis: A.M.S., A.E.R.P. Funding acquisition: A.E.R.P. Writing—original draft: A.L., C.A.H., A.E.R.P. Writing—review & editing: A.L., A.M.S., W.R.U., S.M.S., C.A.H., A.E.R.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

The survey received approval as an exempt study by the University of Iowa institutional review board (IRB). At the beginning of the survey respondents were informed of the voluntary nature of the study, assured that no personal information would be collected, and provided with contact information for the principal investigator and IRB. Consent was presumed for those who continued to complete the survey. Compensation of a cash honorarium was provided through Qualtrics to those who completed the entire survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Unfortunately the part Results in the abstract was given incorrect. The correct text is given below. RESULTS: Overall, participants had a mean age of 43.1 (SD = 13.9), 51.8% identified as female, 63.1% identified as non-Hispanic White, and 38.4% had ≥4-year college degree. Respondents reported relatively low subjective knowledge of GINA (M = 3.10, SD = 1.98; 7-point Likert scale). Among respondents reporting high subjective knowledge of GINA (16.2%), 92.6% incorrectly reported or did not know that GINA does not covers life, long-term care, and disability insurance, and this number was 82.4% for auto or property insurance. Respondents were relatively likely to decline genetic testing due to concerns about results being used to determine eligibility for employment (M = 4.68, SD = 1.89) or health insurance (M = 4.94, SD = 1.73). There were few consistent demographic associations with either subjective or objective knowledge of GINA.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lenartz, A., Scherer, A.M., Uhlmann, W.R. et al. The persistent lack of knowledge and misunderstanding of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) more than a decade after passage. Genet Med 23, 2324–2334 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-021-01268-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-021-01268-w

This article is cited by

-

Community concerns about genetic discrimination in life insurance persist in Australia: A survey of consumers offered genetic testing

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

Expectations, concerns, and attitudes regarding whole-genome sequencing studies: a survey of cancer patients, families, and the public in Japan

Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Reflections on Turkish Personal Data Protection Law and Genetic Data in Focus Group Discussions

NanoEthics (2022)