Abstract

Purpose

To explore parental experiences of ultrarapid genomic testing for their critically unwell infants and children.

Methods

Parents of critically unwell children who participated in a national ultrarapid genomic diagnosis program were surveyed >12 weeks after genomic results return. Surveys consisted of custom questions and validated scales, including the Decision Regret Scale and Genomics Outcome Scale.

Results

With 96 survey invitations sent, the response rate was 57% (n = 55). Most parents reported receiving enough information during pretest (n = 50, 94%) and post-test (n = 44, 83%) counseling. Perceptions varied regarding benefits of testing, however most parents reported no or mild decision regret (n = 45, 82%). The majority of parents (31/52, 60%) were extremely concerned about the condition recurring in future children, regardless of actual or perceived recurrence risk. Parents whose child received a diagnostic result reported higher empowerment.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insight into parental experiences of ultrarapid genomic testing in critically unwell children, including decision regret, empowerment, and post-test reproductive planning, to inform design and delivery of rapid diagnosis programs. The findings suggest considerations for pre- and post-test counseling that may influence parental experiences during the testing process and beyond, such as the importance of realistically conveying the likelihood for clinical and/or personal utility.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Emerging evidence that “rapid” (2–3 weeks) or “ultrarapid” (<7 days) turnaround times impact the clinical utility of genomic testing in critically unwell infants and children is driving widespread uptake.1,2,3,4,5 However, little is known about parental experiences of ultrarapid genomic testing for their critically unwell child, during the testing process and beyond. Elements that complicate pretest counseling in the critical care setting have been described.6,7 In particular, the heightened emotions, burden of parental responsibility,8,9,10 and high pressure clinical decision-making in critical care settings may hinder parents’ ability to consider the distinct significance of genomic testing with regard to the potential implications for their child, themselves, and their family.4,11 There also remains uncertainty among nongenetics health professionals regarding the value of detailed consent for genomic testing in acute pediatric settings.12 However, a growing number of studies highlight the importance of tailored pretest counseling, conveying the potential for receiving unexpected and life-altering information, managing expectations, and providing anticipatory guidance for avoiding potential disappointment and/or decision regret based on unrealistic expectations.6,7,13,14,15 Additionally, the process of informed consent in acute pediatrics can provide parents feelings of control, coping, and empowerment.16 There is emerging evidence that basing pretest counseling on the “generic model” of informed consent (providing general information regarding the potential outcomes of testing) and combining this with limited tailored information (providing more in-depth information regarding certain client-specific aspects of genomic testing) may be an effective approach toward establishing sufficient parental comprehension of genomic testing for informed decision-making while avoiding information overload.7,13,17

The value parents derive from genomic testing may be influenced by both perceived clinical utility (usefulness for improved medical outcomes) and perceived personal utility (outcomes not specifically related to the health of the child being tested).18,19 While clinical utility may be defined and imparted by professionals, personal utility is primarily the domain of parents themselves.19 Exploration of personal utility factors may guide pretest counseling, and assist parents in making informed decisions regarding genomic testing.18,20,21 Parents experienced in living with a child who has a rare, undiagnosed condition express confidence in their ability to manage the stress of receiving unexpected or uncertain genomic testing findings,10 however this stress-managing ability may not yet exist for parents whose newborn or child is critically unwell and/or are at the beginning of their diagnostic trajectory. Therefore it is important to prepare parents for the potential that both diagnostic and nondiagnostic genomic testing results may alter management of a critically unwell child,1,4,5,22,23 and/or lead to new uncertainties.6,7 Although changes in reproductive outcomes are an important downstream effect of early genomic testing in rare disease,22 there is a gap in the understanding of how parents integrate and adapt to the imparted genomic test information and how this experience transitions into considerations regarding the process of reproductive planning and other aspects of personal utility.

While there is a growing body of literature describing clinician experiences and counseling considerations in delivering genomic testing in acute pediatrics,3,6,7,12,24 there is limited literature focused on the parents’ lived experiences and their perceptions of test clinical and personal utility.25 Considering the potential for parents of critically unwell infants to be experiencing a crisis state during pretest counseling,7 there is an imperative to conduct research to determine whether parents regret their decision to provide consent for genomic testing in their child and whether they experience personal utility benefits such as empowerment and/or restored reproductive confidence. This study aimed to explore parental experiences of ultrarapid genomic testing for their critically unwell infants and children, during the testing process and beyond, including the previously unmapped areas of decision regret, empowerment, and post-test reproductive planning.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was granted by the Royal Melbourne Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/MH251). Participants provided voluntary, informed consent.

Context

The Australian Genomics Health Alliance Acute Care Genomics study is a national ultrarapid genomic diagnosis program for infants and children admitted to intensive care with suspected monogenic conditions.5 Patients were recruited prospectively during clinical care; parents/guardians received genetic counseling prior to providing their voluntary, informed consent. Ultrarapid exome sequencing (urES) was performed, as a trio where possible, with the aim of issuing results in <5 calendar days. Wherever possible, results were disclosed to the parents/guardians prior to hospital discharge. Pre- and post-test counseling was provided by genetics health professionals, cocounseling with nongenetics health professionals where appropriate.

Participants

Participants were part of the Acute Care Genomics study.5 Survey invitations were sent to the parent/guardian who provided their email address at the time of consent. Invitations were delayed if the care team indicated that a family was highly distressed. Invitations were not sent if families were withdrawn from the study, requested not to receive surveys, did not have or declined to provide an email address, lacked sufficient written English language comprehension, or required support to complete the survey.

Surveys

Survey invitations were sent by email >12 weeks after disclosure of the genomic testing results. If the survey was not completed, a single reminder was sent by email approximately two weeks later. Survey responses were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia.26 The full survey consisted of custom questions and validated scales (see Supplementary Table S1). Participants whose child was deceased at the time of initial survey invitation received a short version of the survey that omitted questions relating to the impact of the condition on the child and respondent. They were not sent a reminder. All the survey questions and scales reported here were administered in both versions of the survey. Scales included in this analysis are the Decision Regret Scale (DRS),27 a five-item questionnaire with five-point Likert scale which assesses regret or remorse about a health-care decision, and the Genomics Outcomes Scale (GOS),28 a six-item questionnaire with five-point Likert scale that captures the theoretical construct of empowerment relating to genomic medicine. The Acute Care Genomics study began recruitment in March 2018. This paper reports data from responses to survey invitations sent before end of November 2019.

Analysis

The experiences of pre- and post-test counseling, recollection of test outcome, perceived value of test, and post-test reproductive planning were interrogated using descriptive statistics. Comparisons were made with clinician reported data where relevant. Using a previously reported DRS analysis method,29 selected for the ability to identify respondents with moderate to strong decision regret, mean scores were obtained and then converted (by subtracting 1 and multiplying by 25) to generate a DRS score ranging from 0 to 100. DRS scores were defined into three categories: no decision regret (DRS score 0), mild decision regret (DRS score 1–25), and moderate to high decision regret (DRS score >25). GOS scores were transformed to range from 0 to 100 (where 100 represents the highest level of empowerment) by converting mean scores (with relevant items reverse coded) by subtracting 1 and multiplying by 25. Differences between respondents whose child’s urES result was diagnostic versus nondiagnostic, and between those whose child was alive versus deceased at the time of survey, were investigated using two-sided t-tests for normally distributed variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non–normally distributed variables. Quantitative data analyses were conducted using Stata 15.1.30 Optional free-text responses were reviewed for content, corrected for grammar and spelling, and used illustratively to explain quantitative results.

RESULTS

Survey respondents

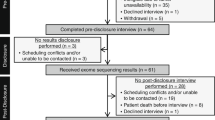

During the study period, 158 families underwent genomic testing through the Acute Care Genomics study and 96 survey invitations were sent, with a response rate of 57% (n = 55). Some survey invitations were delayed beyond the study period on advice of the relevant care team. Respondents were the mother (n = 46, 84%) or father (n = 9, 16%) of the child tested (further demographics in Supplementary Table S2). Response rate was higher for participants whose child was deceased at time of survey (short survey) (17/22, 77%), compared with those whose child was alive (full survey) (38/74, 51%), however there was insufficient power to determine whether this difference was statistically significant. Two parents, one from each group, did not complete beyond survey section 1 and responses from these individuals were omitted from analyses. Therefore 53 surveys were analyzed (96%). Table 1 contains illustrative quotes from free-text responses.

Experiences of pre- and post-test counseling

Most parents reported feeling they received enough information during pretest counseling (n = 50, 94%), had the opportunity to ask all their questions about the test before providing consent (n = 49, 92%), and received enough information during post-test counseling to understand the result (n = 44, 83%). One parent (2%) was unsure if enough pretest information was provided, but felt they had the opportunity to ask all their questions. The two parents (4%) who reported they did not receive adequate pretest information either felt they did not have or were unsure if they had the opportunity to ask all their questions. These parents described their state of heightened distress during pretest counseling due to their child’s acute illness (data not shown), however neither reported any decision regret (DRS score = 0). Comments from some parents who did not feel they received enough information to understand the result (n = 4, 8%), or were unsure if they received enough information (n = 5, 9%), indicated a simpler explanation of the test outcome would have been useful, while others acknowledged their heightened emotional state impacted their ability to understand complex information (Table 1).

Most parents (n = 39, 74%) reported they would not change anything about how the test was offered, or the result explained. Comments from some parents who felt they would (n = 11, 21%) or were unsure if they would (n = 3, 6%) change the process indicated they were dissatisfied with the way results were returned, with multiple parents indicating fewer people in the room at time of results return and/or more time with a genetic counselor would be valuable, while others did not completely understand the limitations of testing (Table 1).

Decision regret

When completing the DRS, respondents were encouraged to think about the decision they made “about agreeing to the genomic sequencing test after talking to the health-care professional”. Over half of parents (n = 31, 58%) had no decision regret, with approximately one quarter (n = 14, 26%) experiencing mild decision regret, and a minority (n = 8, 15%) experiencing moderate to high decision regret. The level of decision regret was comparable between parents whose child received a diagnostic or nondiagnostic urES result, and whose child was alive or deceased at the time of survey (Table 2). Comments from all sections of the survey were examined for the eight parents (15%) who experienced moderate to high decision regret. Six did not provide explanatory comments (DRS scores 30, 30, 40, 40, 50, and 100). The child of the latter parent (DRS score = 100) died during sample processing and their nondiagnostic urES result was returned by phone at family request. Of the remaining two parents who experienced moderate to high decision regret, one did not reflect on their choice to have the test and instead expressed disappointment genomic testing was not offered during pregnancy (DRS score 35). The other expressed that although a diagnosis was received, this provided “no more certainty” (DRS score 75) (Table 1). Comments from parents with no or mild decision regret reinforced they were happy with their decision and identified benefits including the knowledge a diagnosis was able to provide, the impact on their child’s treatment and management, and the consequences for reproductive planning (Table 1).

Perceived value of rapid test

After being reminded their child “had a rapid genomic test, which means the result was available more quickly than usual”, the majority of parents reported it was “very important” (n = 46, 87%) or “important” (n = 6, 11%) the result was available quickly. One parent (2%) reported it was “neither important nor unimportant”, and no parents reported it to be “unimportant”. The perceived importance of rapid time to result was comparable between parents whose child received a diagnostic or nondiagnostic urES result, and whose child was alive or deceased at the time of survey (Table 2). Comments revealed parents valued the ability of urES to affect treatment or management for their child (including avoiding unnecessary intervention), to provide early information about their child’s condition, and the reduction in stress and anxiety from a fast diagnosis (Table 1). Some parents drew comparisons between urES testing and testing with longer wait times, and hypothesized what their experience may have been if this test followed a similar timeline.

Parents were asked if, in their opinion, the rapid time to result made a difference to their child’s care: yes (n = 26, 49%), unsure (n = 4, 8%), no (n = 23, 43%). Most responses (n = 34, 64%) correlated with the assessment by clinicians on change in management as a result of the rapid genomic test.5 Parents whose child received a diagnostic urES result were more likely to select “yes” (Table 2), however there was insufficient power to determine whether this difference was statistically significant. Comments appeared to vary depending on clinical outcome (Table 1). Parents commented on the clinical and psychological impact of a rapid result, highlighting a rapid result allows relevant clinical decisions to be made sooner regardless of diagnostic outcome.

Post-test reproductive planning

Some parents did not answer one or more questions relating to their post-test reproductive planning (survey section 4). The majority of parents (40/53, 75%) reported their perceived reproductive risk (pRR) using a slider bar (0–100%). Of those for whom an actual reproductive risk (aRR) was established, most (20/25, 80%) reported a pRR corresponding to their aRR (Fig. 1). Where an aRR was not established, pRR varied widely (range 0–75%) (Fig. 1). Over half of parents (31/52, 60%) indicated they were extremely concerned about the condition recurring in future children, with the remainder indicating they were moderately concerned (15/52, 29%) or not concerned (6/52, 12%). There was no correlation between level of concern and perceived or actual reproductive risk (Fig. 1). The majority of parents (36/53, 68%) indicated the genomic testing did not have an impact on whether or not they want more children. However, many of these parents also clearly indicated in the comments they would use information from urES testing to guide their use of reproductive services in future, including demonstrating awareness of options such as prenatal diagnosis and preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Others indicated their family was already complete. From the parents who indicated the test did impact on whether or not they want more children (17/53, 32%), comments reflected concern regarding the potential for another affected child (Table 1). Some parents (both with diagnostic and nondiagnostic urES for their child) indicated the test restored their reproductive confidence. Some families, however, remained focused on the existing and emerging care needs of their unwell child.

Empowerment

When completing the GOS, parents were advised “the questions below will help us understand whether the rapid genomic sequencing test helps you and your family with the condition for which testing was offered”. The average GOS score was 60 (SD 17.0, range 29–100). Parents whose child received a diagnostic urES result were more likely to have a higher level of empowerment (mean GOS score 64, SD 16.1, range 42–100), compared with those whose child received a nondiagnostic urES result (mean GOS score 54, SD 16.3, range 29–88). The observed difference between these two groups was statistically significant (p = 0.041), with 64% power, and the distribution is illustrated in Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

For parents consenting to ultrarapid genomic testing in their critically unwell child, initial awareness of both the possibility that their child has an underlying genetic condition and the availability of genomic testing often occurs during, or a short time prior to, being approached for pretest counseling.5,6,7 Most parents who responded to the survey did not regret their decision to proceed with testing, despite concerns that rapid timeframes and other factors of the acute pediatric setting may threaten elements of informed consent,6,16 and that parents’ emotional distress or perceived urgency of testing may lead them to provide consent without fully appreciating implications of genomic testing.31 Some parent comments highlight difficulties in absorbing complex information at pretest counseling (Table 1), such as the established difficulty to fully grasp genomic testing limitations.13 However, overall responses corroborate with literature that individuals can be comfortable with the amount of pretest information provided and their opportunity to ask questions without needing to understand the details of genomic testing.32 These findings may also indicate pretest counseling was appropriately client-centered, as is particularly important for facilitating informed decision-making in the critical care setting,6,7 with the realistic potential for clinical and/or personal utility sufficiently addressed. It has been reported that parents may attribute utility to genomic testing results regardless of clinical outcome.33 However, achieving a diagnosis is often the primary motivation for parents to pursue genomic testing in their critically unwell child,3 with some parents maintaining falsely elevated hope that genomic testing will lead to targeted treatments or miraculous recovery for their child.21,34 Therefore, considering the six parents with moderate to high decision regret who did not provide further explanation, it would be worth exploring whether a potential discrepancy between expectations and the reality of testing might relate to subsequent decision regret. While pretest counseling has an important role in minimizing potential for parental decision regret,6,35 other factors may also trigger regret, as evidenced by the parent who expressed sadness that testing was not offered in utero (Table 1). Further qualitative exploration of these factors with families experiencing decisional regret would be of value in informing the design and delivery of rapid diagnosis programs.

The vast majority of parents valued the rapid time to result, which may reflect reported parental awareness and/or hope the results could potentially influence treatment or management for their critically unwell child.3 Despite many parents likely being unfamiliar with the diagnostic odyssey common in pediatric genetics, instead experiencing mere days between pre- and post-test counseling in ultrarapid testing, their comments (Table 1) echoed published parental sentiments that a protracted wait for potentially life-changing genomic testing results would be challenging.36,37 Compared with pretest counseling, more parents reported they may not have received sufficient post-test information, possibly relating to the lack of information available regarding rare disease diagnoses,7,38 and/or indicating post-test counseling involves more complex discussion. The few parents reporting they would change something about the testing experience expressed dissatisfaction with the return of their results (Table 1), which may indicate a need for additional post-test support.38 Consistent with published findings,36,37 parent comments (Table 1) suggest some parents prefer more post-test information and support than was provided, while others felt it was not relevant to understand all the factual details relating to the result. These parent comments highlight the importance of tailoring post-test counseling and resources and careful consideration of the setting for result return. Additionally, it is important to consider the family experience of different result return settings, as clinical experiences reportedly shape parent feelings about genomic testing regardless of result.34 Parent comments align with existing literature that face-to-face results return is preferred.36 Parents specifically noted that result return by phone or as part of large multidisciplinary “family meetings” is not necessarily ideal, and parents valued dedicated time with genetic counselors (Table 1). These findings suggest parents in acute pediatric settings may benefit from a more intimate, face-to-face initial results disclosure with a smaller number of familiar clinicians (i.e., a genetic counselor and medical geneticist), followed by larger family meetings where relevant for clinical care.

Parent comments regarding reasons they valued genomic testing and lacked decision regret (Table 1) concurred with previously published factors of both clinical and personal utility, including changes in treatment or management, gaining knowledge such as prognostic and/or reproductive information, and reduced stress.9,18,19 However, clinicians should remain cognizant that parental reactions to results may be unpredictable and therefore counseling may need to be adjusted accordingly.38 The distribution of parent perceived clinical utility (Table 2), specifically whether rapid time to result made a difference to their child’s care, is related to both diagnostic outcome of testing and clinician perceived clinical utility.5 These potential relationships and their influencers may be explored in future studies with greater statistical power. The few parents unsure if testing made a difference align with published literature reporting parents experience uncertainty regardless of test outcome, often as a result of a continued diagnostic odyssey or a new therapeutic odyssey.7,8,20,21 With the potential for the process of parental decision-making during pretest counseling to empower parents,16 application of the GOS at different stages of the parent experience is recommended to establish elements affecting empowerment and to guide further investigation into parental personal utility of genomic testing in acute pediatrics settings.

Changes in reproductive outcomes are an important downstream effect of early genomic testing in rare disease.22 The personal utility of reproductive planning information may also be a motivator for parents of critically unwell children to pursue genomic testing.3,19 Although there is variability in parent-reported post-test reproductive planning, findings in this study align with emerging evidence that establishing genetic diagnoses in critically unwell children can restore parental reproductive confidence and impact reproductive outcomes.22,39 Parent comments also indicate reproductive confidence can be restored as a result of nondiagnostic genomic testing, supporting the published concept that such results may also be valued by parents.33 Some parents reported their existing child’s care needs were a more significant factor when considering reproductive planning than recurrence risk. Data obtained indicate most parents could accurately recall their reproductive risk (Fig. 1). However, perceived level of recurrence risk does not predicate level of concern (Fig. 1), highlighting the need to remain client-centered when considering the appropriateness of and approach to discussing reproductive planning during the results disclosure session.

With survey invitations sent at a minimum of three months after result return, many parents would have experienced additional events that shaped their perception of the genomic testing process and results, such as changes in their child’s prognosis, treatment, or management; additional follow up genetic counseling encounters; and/or the death of their child. Although we did not measure a priori empowerment, devising this alternative application of the GOS to measure parental empowerment in the months after genomic testing in their critically unwell child has yielded interesting data warranting further research (Fig. 2). While parents of deceased children are often excluded from research participation due to concerns regarding the potential to cause undue distress, valuable insights were gained from these parents’ responses in our study. The higher response rate and extensive free-text comments indicate this survey may have provided an otherwise lacking avenue for these parents to document their experiences. With the potential for rapid genomic diagnosis to facilitate family counseling regarding end-of-life care decisions focused on alleviating suffering, and to support the grieving process,23,40 it would be valuable for future studies to further explore these parents’ experiences. For example, administering the GOS questionnaire at multiple time points in the testing process could test the hypothesis that direction to palliation as an outcome of ultrarapid genomic testing in critically unwell pediatric patients may increase parent empowerment in an otherwise fraught situation.

Although survey invitations were sent to all eligible families from the Acute Care Genomics national ultrarapid genomic diagnosis program, the small sample size limited statistical power of this study despite the high response rate. The survey intentionally did not seek to assess genomic comprehension. Eligible children were not excluded from this genomic diagnosis program based on socioeconomic status and/or parental English language skills. However, due to funding limitations, this study did not capture responses from individuals unable to complete the survey in written English language via electronic distribution, therefore reducing the diversity of experience reported. Parents with low reading literacy and/or English language skills may have greater difficulty understanding information during pre- and post-test counseling. Further research is required to explore the potential need for modification of counseling and information resources for this group, such as provision of a post-test “plain English summary”, as one parent suggested in their survey comments (Table 1). Survey invitations were emailed to only one parent/guardian. Inviting both parents to independently complete the survey may have identified differences between the experiences of mothers and fathers. This study is limited to participants in the Australian public health-care system, however, the findings arguably reflect the diversity of human experiences and provide the foundation for future research in relating to parent experiences with genomics in acute pediatric care.

This study provides valuable insight into previously unexamined aspects of parental experiences with ultrarapid genomic testing in their critically unwell child, such as decision regret, empowerment, and post-test reproductive planning. The findings highlight considerations for pre- and post-test counseling that may influence parental experiences during the testing process and beyond, such as the need to realistically convey the potential for clinical and/or personal utility during pretest counseling. Additionally, to encourage family-centered care in this emerging area of clinical genetics practice, pretest counseling may be used as an opportunity to determine parental preference for how and with whom initial results disclosure occurs. Further quantitative and qualitative exploration of parent experiences of ultrarapid genomic testing is recommended, including family supports, the impact of parental responsibility on decision-making, perceived value of clinical and personal utility elements, factors affecting changes in level of empowerment, potential impacts on parent–child bonding, and other long-term psychosocial effects. As rapid genomic testing becomes established as a first-tier test in critically unwell infants and children, understanding parental experiences, opinions, perceptions of utility, and the short- and long-term impacts on families will guide the design and delivery of rapid genomic diagnosis programs.

References

Meng L, Pammi M, Saronwala A, et al. Use of exome sequencing for infants in intensive care units: ascertainment of severe single-gene disorders and effect on medical management. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:e173438.

Petrikin JE, Cakici JA, Clark MM, et al. The NSIGHT1-randomized controlled trial: rapid whole-genome sequencing for accelerated etiologic diagnosis in critically ill infants. NPJ Genom Med. 2018;3:6.

Smith EE, du Souich C, Dragojlovic N, et al. Genetic counseling considerations with rapid genome-wide sequencing in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:263–272.

Stark Z, Lunke S, Brett GR, et al. Meeting the challenges of implementing rapid genomic testing in acute pediatric care. Genet Med. 2018;20:1554–1563.

Lunke S, Eggers S, Wilson M, et al. Feasibility of ultrarapid exome sequencing in critically ill infants and children with suspected monogenic conditions in the Australian public healthcare system. JAMA. 2020;323:2503–2511.

Diamonstein CJ. Factors complicating the informed consent process for whole exome sequencing in neonatal and pediatic intensive care units. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:256–262.

Ayres S, Gallacher L, Stark Z, Brett GR. Genetic counseling in pediatric acute care: reflections on ultrarapid genomic diagnoses in neonates. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:273–282.

Hayeems RZ, Babul-Hirji R, Hoang N, et al. Parents’ experience with pediatric microarray: transferrable lessons in the era of genomic counseling. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:298–304.

Anderson JA, Meyn MS, Shuman C, et al. Parents perspectives on whole genome sequencing for their children: qualified enthusiasm? J Med Ethics. 2016;43:535–539.

Sapp JC, Dong D, Stark C, et al. Parental attitudes, values, and beliefs toward the return of results from exome sequencing in children. Clin Genet. 2014;85:120–126.

Woolley N. Crisis theory: a paradigm of effective intervention with families of critically ill people. J Adv Nurs. 1990;15:1402–1408.

Knapp B, Decker C, Lantos JD. Neonatologists’ attitudes about diagnostic whole-genome sequencing in the NICU. Pediatrics. 2019;143(Suppl 1):S54–S57.

Tolusso LK, Collins K, Zhang X, et al. Pediatric whole exome sequencing: an assessment of parents’ perceived and actual understanding. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:792–805.

Bernhardt BA, Roche MI, Perry DL, et al. Experiences with obtaining informed consent for genomic sequencing. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167:2635–2646.

Tomlinson AN, Skinner D, Perry DL, et al. “Not tied up neatly with a bow”: professionals’ challenging cases in informed consent for genomic sequencing. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:62–72.

Aubugeau-Williams P, Brierley J. Consent in children’s intensive care: the voices of the parents of critically ill children and those caring for them. J Med Ethics. 2020;46:482–487.

Brett GR, Wilkins EJ, Creed ET, et al. Genetic counseling in the era of genomics: what’s all the fuss about? J Genet Couns. 2018;27:1010–1021.

Kohler JN, Turbitt E, Biesecker BB. Personal utility in genomic testing: a systematic literature review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:662–668.

Urban A, Schweda M. Clinical and personal utility of genomic high-throughput technologies: perspectives of medical professionals and affected persons. New Genet Soc. 2018;37:153–173.

McConkie-Rosell A, Pena LDM, Schoch K, et al. Not the end of the odyssey: parental perceptions of whole exome sequencing (WES) in pediatric undiagnosed disorders. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:1019–1031.

Krabbenborg L, Vissers LELM, Schieving J, et al. Understanding the psychosocial effects of WES test results on parents of children with rare diseases. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:1207–1214.

Stark Z, Schofield D, Martyn M, et al. Does genomic sequencing early in the diagnostic trajectory make a difference? A follow-up study of clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness. Genet Med. 2019;21:173–180.

Farnaes L, Hildreth A, Sweeney NM, et al. Rapid whole-genome sequencing decreases infant morbidity and cost of hospitalization. NPJ Genom Med. 2018;3:10.

Elliott AM, du Souich C, Lehman A, et al. RAPIDOMICS: rapid genome-wide sequencing in a neonatal intensive care unit—successes and challenges. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178:1207–1218.

Berrios C, Koertje C, Noel-MacDonnell J, et al. Parents of newborns in the NICU enrolled in genome sequencing research: hopeful, but not naïve. Genet Med. 2020;22:146–422.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381.

Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a Decision Regret Scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:281–292.

Grant PE, Pampaka M, Payne K, et al. Developing a short-form of the Genetic Counselling Outcome Scale: The Genomics Outcome Scale. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;62:324–334.

Sheehan J, Sherman KA, Lam T, Boyages J. Association of information satisfaction, psychological distress and monitoring coping style with post-decision regret following breast reconstruction. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:342–351.

Stata Statistical Software: release 15 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017.

Gyngell C, Newson AJ, Wilkinson D, et al. Rapid challenges: ethics and genomic neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics. 2019;143(Suppl 1):S14–S21.

Tabor HK, Stock J, Brazg T, et al. Informed consent for whole genome sequencing: a qualitative analysis of participant expectations and perceptions of risks, benefits, and harms. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1310–1319.

Mollison L, O’Daniel JM, Henderson GE, et al. Parents’ perceptions of personal utility of exome sequencing results. Genet Med. 2020;22:752–757.

McConkie-Rosell A, Sullivan J. Genetic counseling-stress, coping, and the empowerment perspective. J Genet Couns. 1999;8:345–357.

Clift K, Macklin S, Halverson C, et al. Patients’ views on variants of uncertain significance across indications. J Community Genet. 2020;11:139–145.

Krabbenborg L, Schieving J, Kleefstra T, et al. Evaluating a counseling strategy for diagnostic WES in paediatric neurology: an exploration of parents’ information and communication needs. Clin Genet. 2016;89:244–250.

Baumbusch J, Mayer S, Sloan-Yip I. Alone in a crowd? Parents of children with rare diseases’ experiences of navigating the healthcare system. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:80–90.

Macnamara EF, Schoch K, Kelley EG, et al. Cases from the Undiagnosed Diseases Network: the continued value of counseling skills in a new genomic era. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:194–201.

van Diemen CC, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Bergman KA, et al. Rapid targeted genomics in critically ill newborns. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20162854.

Smith LD, Willig LK, Kingsmore SF. Whole-exome sequencing and whole-genome sequencing in critically ill neonates suspected to have single-gene disorders. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a023168.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants for their involvement; Marion McAllister and Peter Grant, authors of the Genomics Outcome Scale, for providing and allowing use of this scale prior to publication; Kate Francis for guidance in use of Stata; and Rigan Tytherleigh for assistance in preparing Supplementary Table S2. The Acute Care flagship project was also supported by a Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation grant (2017-906), and Sydney Children’s Hospital Network, Channel 7 Children’s Research Foundation Grant. The authors are funded by the Australian Genomics Health Alliance, the Melbourne Genomics Health Alliance and the State Government of Victoria (Department of Health and Human Services). F.L. is supported by a Melbourne Children’s Postgraduate Health Research Scholarship funded by the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation. The Australian Genomics Health Alliance (Australian Genomics) project is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Targeted Call for Research grant (GNT1113531). The research conducted at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute was supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brett, G.R., Martyn, M., Lynch, F. et al. Parental experiences of ultrarapid genomic testing for their critically unwell infants and children. Genet Med 22, 1976–1985 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-020-0912-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-020-0912-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation and pilot testing of a multidisciplinary model of care to mainstream genomic testing for paediatric inborn errors of immunity

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Re: “Next generation sequencing in neonatology: what does it mean for the next generation?”

Human Genetics (2023)

-

Co-design, implementation, and evaluation of plain language genomic test reports

npj Genomic Medicine (2022)

-

‘Diagnostic shock’: the impact of results from ultrarapid genomic sequencing of critically unwell children on aspects of family functioning

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

Rapid genomic testing for critically ill children: time to become standard of care?

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)