Abstract

Ophthalmology faces many challenges in providing effective and meaningful eye care to an ever-increasing group of people. Even health systems that have so far been able to cope with the quantitative patient increase, due to their funding and the availability of highly qualified professionals, and improvements in practice routine efficiency, will be pushed to their limits. Further pressure on care will also be caused by new active substances for the largest group of patients with AMD, the so-called dry form. Treatment availability for this so far untreated group will increase the volume of patients 2–3 times. Without the adaptation of the care structures, this quantitative and qualitative expansion in therapy will inevitably lead to an undersupply.There is increasing scientific evidence that significant efficiency gains in the care of chronic diseases can be achieved through better networking of stakeholders in the healthcare system and greater patient involvement. Digitalization can make an important contribution here. Many technological solutions have been developed in recent years and the time is now ready to exploit this potential. The exceptional setting during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has shown many that new technology is available safely, quickly, and effectively. The emergency has catalyzed innovation processes and shown for post-pandemic time after that we are equipped to tackle the challenges in ophthalmic healthcare - ultimately for the benefit of patients and society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Digitalization accelerates change

Digitalization has radically changed many areas of our lives. Astonished teenagers listen with eyes wide to the stories of cassette recorders, booking air travel on the telephone, looking through library card index for research, or visiting the bank teller to withdraw money for the week. Growing up in a world of Spotify, travel portals, AirBnB, Amazon, Google, Neobanks and multiplayer online games, these tales seem like stories from an old, distant world, even though they were the norm a mere few decades ago.

Conversely, such disruptive and radical changes have not yet occurred in the medical domain [1]. Despite the availability of technology for the purpose of delivering digital first solutions such as electronic medical records, algorithmically supported image analysis and remote diagnosis with telemedicine, change in healthcare has been slower, more cautious, and unequally distributed compared to industries such as retail, commerce, or banking [2, 3].

Digitalization in medicine

Many areas of medical care have remained essentially unchanged for half a century. Medical practice remains to a large extent institution-bound and doctor-centred [4]. The patiens [lat] - the patiently sufferer, goes to the place of medical knowledge - the medical centre - to obtain advice on the existence and the course of (his) disease. While digitalization has led to comprehensive customer-centricity in many areas, such examples are rare in medicine. While doctor-centred institution-bound care will remain important throughout digital innovation in medicine, it will be crucial to determine which aspects of care can be decentralized to the benefit of relieving the pressure of healthcare systems, patients, and medical personnel. Approaches to greater patient-centricity and more decentralized care can be observed in chronic diseases such as bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure and diabetes mellitus (summarized in [5]). For some, rarer diseases, so-called home care approaches have become established, in which patients are visited at home by specialized nurses and treated with infusions, for example [6].

Digitalization in ophthalmology — hurdles and opportunities

In ophthalmology, new approaches making benefit of innovative digital solutions have been developed, particularly in Northern Europe, the UK and Australia, partly in national programmes, in the care of patients with chronic retinal diseases such as diabetic macular oedema (DMO) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Both conditions are chronic and lead to severe visual impairment if left untreated. If detected, they can be controlled albeit with complex, variable, frequent and prolonged treatments regimes - the regular application of the active substance directly into the eye several times a year. The strain on the patient and their carers to follow such a therapy for a longer period of time is considerable [22]. Unfortunately, we still observe too many therapy discontinuations and only some of the reasons are known including low vision at baseline and extent of co-morbidity [23]. This occurs despite overwhelming evidence that therapy interruptions lead to a lack of care, which results in vision loss and a large national disease burden and in many regions treatment discontinuation is not detected and acknowledged. However, it may be difficult for ophthalmologists to perceive this problem in their daily practice.

Many initiatives, including telemedicine services or home-monitoring programmes aimed at introducing digital innovations into ophthalmic care to combat treatment disruptions are still in their infancy, despite their medical and economic importance. The obstacles to implementing innovation are complex and country specific. In a survey of global experts in retinal diseases on their views on the introduction of digital health applications, many were rather sceptical. The lack of reimbursement for these kinds of services was the main reason cited for not offering tele-ophthalmology, a barrier that was removed during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [1].

A lack of pressure to innovate and a lack of incentive systems, regulatory concerns such as data security and unsuitable tariff structures for mapping innovative care systems in existing remuneration models and financial losses on the part of the physician are other frequently cited factors. Again, the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the associated lockdown abruptly changed this in many countries [24].

In most countries, outpatient ophthalmology services were largely disrupted if not completely halted within days. Patients feared infection in hospital, medical staff were withdrawn to treat Covid-19 patients and regular services were suspended for safety reasons. In the UK, where the impact of the pandemic on ophthalmic care was analyzed in detail, 80% of outpatient consultation capacity was suddenly stopped for several months. In the USA, but also in Switzerland, the processes of follow-up examinations, for example in patients with diabetic retinal diseases, had to be drastically adapted for social distancing purposes. In some cases, vision tests and imaging diagnostics were abandoned and only treatment was given. Furthermore, many patients with chronic eye diseases, who would have needed treatment chose to remain at home and thus risked - and sometimes experienced - permanent vision loss.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic as a catalyst for innovation

In this crisis, the ophthalmologic routine was shaken up and there was suddenly room for new ideas. There was pressure to innovate, and the delivery of care now suddenly had to reach the patient rather than the other way around. Across the globe, initiatives developed to ensure minimal necessary care using home measurements, telemedicine services and telephone consultations [25].

Out of the need to innovate, new types of care structures quickly emerged, which were also able to demonstrate their benefits in scientific studies. New paradigms were created out of pure necessity of the pandemic situation where the patient is at the centre of care. This focus leads to a more decentralized medicine, a stronger networking of different specialists in patient care and - through the inclusion of home measurements - a new quality of data for the monitoring of disease progression. From this interplay, a new vision of ophthalmic care emerges which even today has a great rationale. Table 1 provides a selection of monitoring tests available to assess the visual system at home.

The new supply reality

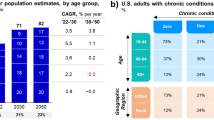

The care of AMD and DMO is facing major challenges due to socio-demographic change. According to the latest figures, the number of patients with AMD will rise from around 200 to 290 million worldwide by 2040, and the number of patients with diabetes from around 400 to 650 million [26, 27]. In Switzerland for example, the number of patients with AMD and DMO treated with intravitreal injections is currently estimated at approximately 30,000. Around 350 ophthalmologists currently administer around 170 thousand injections per year. In recent years, the market for intravitreal injections has grown by about 17 percentage points per year [28]. Due to demographic changes, the AMD market will grow significantly over the next two decades.

If care remains the same, treatment bottlenecks are to be expected only from demographic shifts. Moreover, further pressure on care will soon be caused by drugs targeting at the much larger group of patients with the so-called dry form of AMD. Two pivotal phase 3 trials on the treatment of advanced dry AMD were recently finalized and are currently submitted to the regulatory authorities [29]. This will increase the volume of patients many times over.

Pharmaceutical companies are already advanced in developing innovative therapy options with reduced number of annual treatments. In addition, two novel therapy concepts for AMD and DMO are about to enter the market, which can reduce the therapy intensity to half or even one third [30,31,32]. Although these innovations will bring initial relief to the care system, care efficiency must also increase and attractive, innovative reimbursement models must be implemented [1].

Individualization of treatment — Personalized Healthcare

Ideally, treatment is directed to the specific treatment needs of a patient. If the condition is stable and no treatment is needed at the medical centre, there should be no in person consultation. The so-called treat and extend strategy is already in use in many patients and combines a clinical follow-up with the treatment visit. But due to possible appointment delays and deterioration in the fellow untreated eye, an additional safety net is necessary, especially for patients with long treatment intervals. If treatment is necessary, it should be possible to provide it flexibly. In principle, this ideal type of care is within reach because all the necessary organizational and technological requirements are already in place. Ironically, one is almost inclined to say, it was the pandemic crisis that opened our eyes to this. It highlights again that social and medical transition cannot be planned; sometimes it progresses slowly, sometimes quickly based on crisis and need [33].

An important piece of the puzzle of this care is the patient’s simple self-measurement of the course of the disease. The data from these measurements are automatically categorized (green, yellow, red) and sent to the attending physician or the clinic via telemedicine platforms and the patient receives instant feedback about his status. If the data show abnormalities in the sense of a worsening of the disease, the clinic contacts the patient and plans further care or vice versa and needs to be agreed with the patient initially. Currently, two mobile applications that test a specific visual function and can be used on smartphones or tablets. Clinical studies have shown that therapy management through self-measurement with home monitoring assessing visual function is able to identify the group of patients who need treatment [11, 12, 15, 17, 20, 24]. Very recently, also a mobile imaging device (Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)) has become available for home measurement by the patient, providing real-life structural retina data [16]. A few home OCT devices have already been tested for their applicability in clinical studies [18, 34]. Ultimately, a home measurement system creates an additional opportunity of patient doctor interaction and a channel to address fears and uncertainties regarding the therapy.

Relief from physician-centred care structures

Such an innovative and patient-centred care system could be supplemented by the inclusion of other non-medical stakeholders who care for the patient regarding visual function if patient number pressure requires it. It is readily conceivable that regular imaging examinations – which are typically performed in hospitals or by specialists in private practice and provide the indication to treat according to the guidelines – could be performed in a decentralized system at the optician’s or pharmacist’s premises under the supervision of ophthalmologists and in conformity with the legal system.

If patients are severely restricted in their mobility, a team of non-medical specialists can also carry out a basic ophthalmological examination with a telemedical assessment on site within a home care framework. Such a service has been available in Switzerland for about two years and is reimbursed by health insurances [35]. Patients and doctors can derive a lot of benefit from this additional service. For patients, the hurdle to accessing medical care is noticeably reduced and the attending physicians can create the necessary organizational prerequisites before the doctor’s visit to ensure an efficient examination and treatment due to the information they receive from the referring service.

Image analysis can also be performed by specially trained non-medical professionals, supported by automated image analysis outside the hospital in a reading centre. Reading centres and other specialists with the help of retina experts are the ones who currently develop AI based systems which should be able to decide if there is disease activity and make treatment suggestions, e.g., treatment intervals [10, 14, 21, 36,37,38]. In the UK, a national system organized in this way to detect diabetics with retinal diseases requiring treatment has led to a marked reduction in legal blindness and an improvement in care without the need to increase medical staff [19]. Key of these approaches is the hybrid model, combining advanced imaging technology with an initial automated assessment, followed by a second human virtual re-examination if needed.

Reduction of opportunity costs for patients and their relatives

The organization of treatment for AMD and DMO also has resource-binding consequences for the patient, carer and relatives. However, reliable study data on this subject are hard to find [22]. Going to a medical consultation and treatment often requires accompanying persons who will stay away from work during this time, driving services and planning. In the best case, these efforts are limited to times when the use of medical services is indispensable. The introduction of a telemedicine service at the renowned Moorfields Eye Hospital in London during the lockdown in 2020 reduced the number of patient journeys by 1.4 million kilometres in the emergency department alone. It saved patients and their carers 6.4 years of travel time and avoided the equivalent of 51,000 litres of CO2 emissions from petrol (Dr Dawn Sim, personal communication).

Outlook

Ophthalmology faces many challenges in providing effective and meaningful eye care to an ever-increasing group of people. Even the health systems that have so far been able to cope will face similar pressures of a global aging demographic and need for highly qualified professionals. The digital era offers new innovative approaches to decentralized, personalize, and democratize eye care for patients whilst allowing the healthcare workforce to practice at the top of their license. The overwhelming challenges for ophthalmologists in the coming years to cope with the large number of additional patients in the practice require a concerted interaction of new therapeutic approaches, technological innovations but also regulatory support and incentive systems so that the change can be initiated in time. To this end, it is also necessary to provide training for professionals on the new technologies and possibilities so that sufficient competence is built up for the implementation of new care structures.

Data availability

No research data are provided in this manuscript.

References

Faes L, Rosenblatt A, Schwartz R, Touhami S, Ventura CV, Chatziralli IP, et al. Overcoming barriers of retinal care delivery during a pandemic-attitudes and drivers for the implementation of digital health: a global expert survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105:1738–43.

Herzlinger RE. Why innovation in health care is so hard. Harv Bus Rev. 2006. https://hbr.org/2006/05/why-innovation-in-health-care-is-so-hard

Hjelm NM. Benefits and drawbacks of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11:60–70.

Wasan KM, Berry L, Kalra J. Physician centric healthcare: is it time for a paradigm shift? J R Soc Med. 2017;110:295–6.

Noah B, Keller MS, Mosadeghi S, Stein L, Johl S, Delshad S, et al. Impact of remote patient monitoring on clinical outcomes: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:20172.

Polinski JM, Kowal MK, Gagnon M, Brennan TA, Shrank WH. Home infusion: Safe, clinically effective, patient preferred, and cost saving. Health. 2017;5:68–80.

Abramoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:39.

Chopra R, Wagner SK, Keane PA. Optical coherence tomography in the 2020s-outside the eye clinic. Eye. 2021;35:236–43.

Choremis J, Chow DR. Use of telemedicine in screening for diabetic retinopathy. Can J Ophthalmol. 2003;38:575–9.

Faes L, Fu DJ, Huemer J, Kern C, Wagner SK, Fasolo S, et al. A virtual-clinic pathway for patients referred from a national diabetes eye screening programme reduces service demands whilst maintaining quality of care. Eye. 2021;35:2260–9.

Faes L, Islam M, Bachmann LM, Lienhard KR, Schmid MK, Sim DA. False alarms and the positive predictive value of smartphone-based hyperacuity home monitoring for the progression of macular disease: a prospective cohort study. Eye. 2021;35:3035–40.

Gross N, Bachmann LM, Islam M, Faes L, Schmid MK, Thiel MA, et al. Visual outcomes and treatment adherence of patients with macular pathology using a mobile hyperacuity home-monitoring app: a matched-pair analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e056940.

Group AHSR, Chew EY, Clemons TE, Bressler SB, Elman MJ, Danis RP, et al. Randomized trial of a home monitoring system for early detection of choroidal neovascularization home monitoring of the Eye (HOME) study. Ophthalmology 2014;121:535–44.

Gupta A, Cavallerano J, Sun JK, Silva PS. Evidence for Telemedicine for Diabetic Retinal Disease. Semin Ophthalmol. 2017;32:22–8.

Islam M, Sansome S, Das R, Lukic M, Chong Teo KY, Tan G, et al. Smartphone-based remote monitoring of vision in macular disease enables early detection of worsening pathology and need for intravitreal therapy. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021;28:1–7.

Keenan TDL, Goldstein M, Goldenberg D, Zur D, Shulman S, Loewenstein A. Prospective, longitudinal pilot study: daily self-imaging with patient-operated home OCT in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Sci. 2021;1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xops.2021.100034.

Korot E, Pontikos N, Drawnel FM, Jaber A, Fu DJ, Zhang G, et al. Enablers and barriers to deployment of smartphone-based home vision monitoring in clinical practice settings. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140:153–60.

Maloca P, Hasler PW, Barthelmes D, Arnold P, Matthias M, Scholl HPN, et al. Safety and feasibility of a novel sparse optical coherence tomography device for patient-delivered retina home monitoring. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2018;7:8.

Scanlon PH. The English National Screening Programme for diabetic retinopathy 2003-2016. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54:515–25.

Schmid MK, Thiel MA, Lienhard K, Schlingemann RO, Faes L, Bachmann LM. Reliability and diagnostic performance of a novel mobile app for hyperacuity self-monitoring in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Eye. 2019;33:1584–9.

Shi L, Wu H, Dong J, Jiang K, Lu X, Shi J. Telemedicine for detecting diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:823–31.

Vukicevic M, Heraghty J, Cummins R, Gopinath B, Mitchell P. Caregiver perceptions about the impact of caring for patients with wet age-related macular degeneration. Eye. 2016;30:413–21.

Westborg I, Rosso A. Risk factors for discontinuation of treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018;25:176–82.

Teo KYC, Bachmann LM, Sim D, Lee SY, Tan A, Wong TY, et al. Patterns and characteristics of a clinical implementation of a self-monitoring program for retina diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ophthalmol Retin. 2021;5:1245–53.

Patel S, Hamdan S, Donahue S. Optimising telemedicine in ophthalmology during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Telemed Telecare. 2022;28:498–501.

Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Cho NH, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40–50.

Wong WL, Su X, Li X, Cheung CM, Klein R, Cheng CY, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e106–16.

Chopra R, Preston GC, Keenan TDL, Mulholland P, Patel PJ, Balaskas K, et al. Intravitreal injections: past trends and future projections within a UK tertiary hospital. Eye. 2022;36:1373–8.

Apellis Pharmaceuticals I. Study to compare the efficacy and safety of intravitreal APL-2 therapy with sham injections in patients with geographic atrophy (GA) secondary to age-related macular degeneration. 2021. https://www.clinicaltrialsgov/ct2/show/NCT03525600.

Heier JS, Khanani AM, Quezada Ruiz C, Basu K, Ferrone PJ, Brittain C, et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of intravitreal faricimab up to every 16 weeks for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (TENAYA and LUCERNE): two randomised, double-masked, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet. 2022;399:729–40.

Holekamp NM, Campochiaro PA, Chang MA, Miller D, Pieramici D, Adamis AP, et al. Archway randomized phase 3 trial of the port delivery system with ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2022;129:295–307.

Wykoff CC, Abreu F, Adamis AP, Basu K, Eichenbaum DA, Haskova Z, et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of intravitreal faricimab with extended dosing up to every 16 weeks in patients with diabetic macular oedema (YOSEMITE and RHINE): two randomised, double-masked, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;399:741–55.

Kuhn TS. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1970.

Ho AC, Heier JS, Holekamp NM, Garfinkel RA, Ladd B, Awh CC, et al. Real-world performance of a self-operated home monitoring system for early detection of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1355.

Geschwindner H. 2021. https://www.gerontologieblog.ch/augenmobil-bringt-die-augenheilkunde-ins-pflegezentrum/.

Jones L, Bryan SR, Miranda MA, Crabb DP, Kotecha A. Example of monitoring measurements in a virtual eye clinic using ‘big data’. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:911–5.

Kern C, Fu DJ, Kortuem K, Huemer J, Barker D, Davis A, et al. Implementation of a cloud-based referral platform in ophthalmology: making telemedicine services a reality in eye care. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:312–7.

Saleem SM, Pasquale LR, Sidoti PA, Tsai JC. Virtual ophthalmology: telemedicine in a COVID-19 era. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;216:237–42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LF, DAS, and LMB initiated the project and wrote a first draft of the text. All authors made textual additions and provided critical intellectual input. All authors approved the content of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Faes, L., Maloca, P.M., Hatz, K. et al. Transforming ophthalmology in the digital century—new care models with added value for patients. Eye 37, 2172–2175 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02313-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02313-x