Abstract

Background

Recent national data suggests that less than 0.5% of NHS cataract patients undergo immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS). Since ISBCS improves service efficiency, increasing its practice may help tackle the ever-growing burden of cataract in the UK, and reduce the COVID-19 cataract backlog. Surgeon attitudes are known to be a significant barrier to increasing the practice of ISBCS. However, little is known about patient perceptions of ISBCS.

Methods

Patients at cataract clinics across three NHS hospital sites were recruited to complete an investigator-led structured questionnaire. Open-ended and closed-ended questions were used to assess awareness of ISBCS, willingness to undergo ISBCS and attitudes towards ISBCS.

Results

Questionnaires were completed by 183 patients. Mean participant age was 70.5 (9.9) years and 58% were female. Forty-three percent were aware of ISBCS, chiefly via clinic staff. Just over a third would choose ISBCS if given the choice, and participants that perceived they were recommended ISBCS were more likely to opt for it. The most common motivator and barrier to uptake of ISBCS was convenience and the perceived risk of complications in both eyes respectively. Concerns related to the recovery period were common, including misunderstandings, such as the need to wear eye patches that obscure both eyes.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that significantly more NHS patients would be willing to undergo ISBCS if given the choice. The reluctance of surgeons to recommend ISBCS and patient misunderstandings regarding the recovery period may be limiting its uptake.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cataract surgery is already the most frequently performed operation in the NHS, and a 50% increase in cataract prevalence is forecast by 2035 due to the UK’s aging population [1]. This long term growth in demand, compounded by the COVID-19 related backlog of unoperated cataract, has provided impetus to consider what cataract service redesign options exist [1, 2].

Recent Royal College of Ophthalmologists National Ophthalmology Database (NOD) data indicates that less than 0.5% of NHS patients undergoing cataract surgery in both eyes undergo immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS) in which cataract surgery is performed in both eyes on the same day [3]. Since ISBCS is known to be cost-effective and improve operating room efficiency, it has been proposed that increasing its practice may help pave the way for more sustainable cataract services [3,4,5,6].

Surveys conducted prior to the pandemic indicate that hesitancy to offer ISBCS amongst UK based surgeons may be limiting its practice in the NHS, largely due to concerns regarding the risk of bilateral complications such as endophthalmitis [7]. Despite this, a large case series of ISBCS (95,606 patients) reported no incidences of bilateral endophthalmitis, and randomised controlled trials of ISBCS have identified no safety concerns [8,9,10,11].

The COVID-19 pandemic has sparked a greater interest in patient perceptions of ISBCS [12,13,14]. A survey of 267 patients suggested that during the pandemic, 45% of patients on NHS cataract surgery waiting lists would undergo ISBCS if given the choice [13]. While past surveys have provided some valuable insights into patient attitudes towards ISBCS, the use of closed-ended questions has limited participant responses to investigator-provided suggestions, which may overlook more nuanced motivators and barriers to uptake of ISBCS [12,13,14,15]. In addition, since most surveys regarding patient perceptions were conducted during the pandemic, the future relevance of such studies is unclear [12,13,14].

The aim of this study is to quantify the awareness and acceptability of ISBCS and to gain a more complete understanding of patient attitudes by using a questionnaire including open-ended questions. This information will be useful for facilitating service redesign that reflects patient understanding and preferences in relation to ISBCS.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed using an investigator-led structured questionnaire containing open-ended and closed-ended questions. The questionnaire was developed in consultation with ophthalmologists internal and external to the host institution and members of the institution’s Public and Patient Involvement and Service Improvement teams. It was then pre-tested and iteratively refined to optimise comprehension.

Patients were recruited between the 14th of June to the 26th of July 2021 from twenty morning and thirteen afternoon cataract clinics across three hospitals sites of Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Patient recruitment took place until responses to open-ended questions reached saturation and new themes or ideas were no longer being offered.

Ophthalmologists were verbally informed of the study design and asked to invite the following patients to complete the questionnaire at the end of their clinic appointment: (1) cataract surgery-naive patients (patients that have never undergone cataract surgery) with visually significant bilateral cataract listed for first eye cataract surgery or ISBCS, (2) post-operative patients listed for second eye cataract surgery following first eye cataract surgery and (3) post-operative patients that had undergone ISBCS or delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery (DSBCS). Patients that required translation services or were under 18 years old were excluded.

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to completing the questionnaire. Questions were read aloud, and responses were tabulated in summary and recorded in a computer spreadsheet. When there was a lack of clarity, the recorded response was read back to the participant to ensure its accuracy.

The study received ethical approval from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee and was authorised by the host institution’s audit department. All data collection was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participant sex, age and cataract surgical status were obtained directly from hospital records, and employment status was assessed using a closed-ended question. The proportion of participants aware of ISBCS and how these participants became aware was determined using a binary question and an opened-ended question respectively.

To assess patient willingness to undergo ISBCS and attitudes towards ISBCS, participants were asked whether they were given the choice of undergoing ISBCS using a binary question, and whether they had any concern about undergoing ISBCS using an open-ended question. Cataract surgery-naive participants that reported to have been given the choice were asked why they chose to be listed for ISBCS or DSBCS using an open-ended question, and whether the surgeon recommended ISBCS, DSBCS or both options equally using a closed-ended question. The remaining participants were asked whether they would undergo ISBCS if given the choice using a five-point Likert scale, and the reason for this using an open-ended question [16].

Post-operative ISBCS participants were asked whether ISBCS was as expected using a five-point Likert scale and open-ended questions regarding what additional information they would have liked to receive before undergoing ISBCS [16].

For the complete questionnaire used, see the Supplementary Information.

Responses to closed-ended questions are summarised as a proportion of the respondents. Chi-squared tests and unpaired t-tests were conducted to assess for statistical differences in sex, mean age, and employment status between participants that would and would not choose ISBCS using STATA 16.1 (StataCorp. 2019, College Station, TX, USA).

To analyse the responses to the open-ended questions regarding reasons given for choosing and not choosing ISBCS, a list of key phrases was inductively compiled to capture all reasons mentioned. The proportion of responses that contained each reason was calculated for all participants and surgery-naive and post-operative participant subgroups. Due to the similarities in the responses given, reasons for not choosing ISBCS and concerns regarding ISBCS were analysed together. The same method was used for analysing the responses regarding awareness of ISBCS. To summarise responses to the additional questions for post-operative ISBCS participants, representative quotes are reported for each response.

Results

Patient characteristics

Questionnaires were completed by 183 patients. This included 15 (8.2%) cataract surgery-naive participants listed for ISBCS, 51 (27.9%) cataract surgery-naive participants listed for first eye cataract surgery, 73 (39.9%) post-operative participants listed for second eye cataract surgery, 40 (21.9%) post-operative patients that had undergone DBSCS and 4 (2.2%) post-operative patients that had undergone ISBCS.

The mean age (standard deviation) of participants was 70.5 (9.9) years. Seventy-seven (42.1%) participants were male and 106 (57.9%) were female. Ten (5.5%) participants reported to be unemployed, 49 (26.8%) reported to be in full-time or part-time employment and 124 (67.8%) reported to be retired.

Awareness of ISBCS

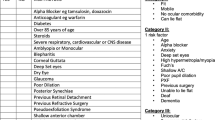

Of the 183 participants, 78 (42.6%) reported being aware of ISBCS. Forty-six (59.0%) of these were aware of ISBCS via clinic staff and 20 (25.6%) were aware via a family member, friend, or acquaintance. Less common sources of awareness included online and hospital patient information, which was reported by 7 (9.0%) and 6 (7.7%) participants respectively. One (1.3%) participant was unsure how they became aware of ISBCS.

Acceptability of ISBCS

Amongst cataract surgery-naive participants, 27/66 (40.9%) reported being offered ISBCS, 15 (55.6%) of which chose to be listed for ISBCS. Of the surgery-naïve participants listed for ISBCS, 6/15 (40%) perceived that the surgeon recommended ISBCS. Of the 12 surgery-naïve participants that declined the offer to be listed for ISBCS, 1 (8.3%) perceived that the surgeon recommended ISBCS, and 1 (8.3%) perceived that the surgeon recommended DSBSC. The remaining 19/27 (70.4%) surgery-naïve participants offered ISBCS perceived that ISBCS and DSBCS were recommended equally.

Of the 9/117 (7.7%) post-operative patients that reported being offered ISBCS in clinic, 4/9 (44.4%) underwent ISBCS.

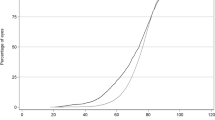

Amongst surgery-naive participants not offered ISBCS and post-operative participants, 15/39 (38.5%) and 36/117 (30.8%) agreed respectively that, if given the choice, they would choose ISBCS (Fig. 1). Of the four post-operative ISBCS participants included, three strongly agreed and one disagreed that they would choose ISBCS if given the choice again. The post-operative ISBCS participant that disagreed that they would choose ISBCS if given the choice again also disagreed that ISBCS was as expected. Among the remaining post-operative ISBCS participants, one agreed, one disagreed and one strongly disagreed that ISBCS was as expected. Representative quotes expressing the reasons that participants did not find ISBCS as expected, and additional information participants would have liked to receive before undergoing ISBCS are shown in Fig. 1.

By combining the 15 surgery-naive participants that chose to be listed for ISBCS and the 51 participants that agreed they would choose ISBCS if given the choice, it can be estimated that 66/183 (36.1%) participants in our study would choose ISBCS. Likewise, by combining the 12 surgery-naive participants that chose not to be listed for ISBCS and the remaining 89 participants that disagreed they would choose ISBCS if given the choice, it can be estimated that 101/183 (55.2%) participants in our study would not choose ISBCS. The remaining 16/183 (8.7%) participants were neutral towards ISBCS (Fig. 2).

As shown in Table 1, there was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.3) in sex, age, and employment status between participants that would and would not choose ISBCS.

Attitudes towards ISBCS

Seventy-nine participants gave reasons for choosing ISBCS and 142 participants gave reasons for not choosing ISBCS or had concerns regarding ISBCS.

Of the participants that gave responses in favour of ISBCS, the most common reason was convenience or time and travel savings, which was reported by 34/79 (43.0%) participants. The second most common reasons (both reported by 22/79 (27.8%) participants) were to avoid the stress of additional operations or appointments and reduction of waiting time for surgery. The next most common reason (reported by 21/79 (26.6%) participants) was to avoid visual imbalance between the first and second surgery. This included participants that reported concerns regarding having to wait until the second surgery for a new spectacle prescription and issues with reading, balance, and vision between operations. Other less common reasons for choosing ISBCS are shown in Table 2.

The most common reason for not choosing ISBCS was the risk of complications in both eyes or concerns about safety, which was reported by 77/142 (54.2%) participants. The second most common concern reported in 48/142 (33.8%) responses was the difficulty of coping with impaired vision in both eyes immediately following the operation.

The only other concerns mentioned in over 10% of responses were regarding the need to wear patches that obscure both eyes after surgery and the need for additional care and support while recovering. All expressed concerns are presented in Table 3.

Discussion

Although NICE guidance [NG77] recommends offering ISBCS to most adult cataract patients, it is not widely performed in the NHS, and thus remains largely unheard-of by cataract patients in the UK [3, 13, 17]. In our study, most patients were recruited in clinics that often offer ISBCS. However, only around 40% of participants reported awareness of ISBCS, most of whom became aware via clinic staff. This suggests that unless patients are actively informed about ISBCS, they are unlikely to be aware of it.

A survey conducted prior to and during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that 45% of patients on NHS cataract surgery waiting lists would undergo ISBCS if offered it [13]. In our cross-sectional study conducted during the post-COVID-19 cataract service rebuild, just over a third (36%) of participants reported that they would undergo ISBCS if given the choice. This implies a slight decline in the acceptability of ISBCS as the pandemic has progressed, possibly due to greater concerns about contracting COVID-19 and longer waiting times for surgery during the earlier phase of the pandemic. Nevertheless, since prior to the pandemic less than 0.5% of NHS cataract surgery recorded on the NOD was ISBCS, our findings suggests that from the patient perspective, a post-pandemic increase in practice of ISBCS would be feasible and welcomed [18].

While our study was undertaken across only three NHS cataract provider sites, the demographics of our study population appeared representative of the UK cataract patient population compared to recent NOD data [18].

Since ISBCS improves operating room efficiency and requires fewer hospital visits, it has been suggested that adopting ISBCS as routine practice may help tackle the growing burden of cataract in the UK [3, 4]. This should make it an attractive option to clinicians looking to facilitate patient-centred service redesign. In our study, patient willingness to undergo ISBCS appeared to be influenced by surgeon recommendation in clinic. Forty percent (6/15) of participants listed for ISBCS perceived that they were recommended it, while only 8% (1/12) of the surgery-naive participants that chose not to be listed for ISBCS perceived they were recommended it. A possible explanation is that since ISBCS is controversial, unconscious personal biases held by surgeons may cause patients to be persuaded either in favour or against ISBCS [7]. Nonetheless, it was encouraging that most participants offered ISBCS (70%) felt that the surgeon offered both choices equally and did not express any preference.

ISBCS is often considered a riskier surgical option than DSBCS, mainly due to concerns regarding complications such as bilateral endophthalmitis [3]. Since research suggests that females and older adults tend to be more risk averse, it was anticipated that these patients would be less likely to be willing to undergo ISBCS [19]. However, there was no significant statistical difference (p > 0.3) between the age and sex of participants that would and would not choose ISBCS. As demonstrated by the diverse list of reasons given by participants in Tables 2 and 3, this may be because decisions regarding ISBCS are highly dependent on individual circumstances. Thus, the decision-making process cannot be easily reduced to patient demographics.

The most popular response in favour of ISBCS was convenience or to save time and travel as there would be fewer hospital visits. It has been estimated that ISBCS requires two fewer hospital appointments than DSBCS [6]. Since most cataract patients are older adults, many of whom have reduced visual function or fragilities, additional travel to and from hospital is often a significant undertaking requiring support from carers and family members. It may also incur further economic costs due to time off work and travel expenses [5, 6].

The risk of complications in both eyes and concerns about safety were reported by over half (54%) of participants that expressed concerns regarding ISBCS. Many ophthalmologists share these concerns with a recent survey finding the risk of bilateral endophthalmitis as the main reason for surgeons deciding not to perform ISBCS in the UK [7]. In clinical practice, the estimated risk of bilateral endophthalmitis typically quoted to patients is “1/250 000” [20]. However, since no cases of bilateral endophthalmitis have been reported following ISBCS adhering to aseptic protocol, it remains a theoretical risk [10].

Another common concern regarding ISBCS is that it removes the opportunity for refractive outcome refinement in the second eye based on outcomes in the first eye [7]. Large case series and randomised controlled trials have not substantiated these fears, and report similar refractive and visual function outcomes for ISBCS and DSBCS [8, 9, 21].

Although fear is a well-recognised barrier to uptake of ISCBS, the role of other related emotions such as anxiety and stress in ISBCS decision-making are relatively unexplored [13]. Anxiety and stress were common motivators for uptake with approximately a quarter (28%) of participants in favour of ISBCS wishing to undergo ISBCS to avoid the anxiety or stress of an additional operation or hospital appointment.

Of the post-operative responses against ISBCS, 4% included concerns regarding the operation length or the need to lie flat for a long time. An additional 4% felt that ISBCS is undesirable as it would be more uncomfortable. Although these were uncommon concerns in our study, this supports previous research suggesting that ISBCS may be less appropriate for patients anxious about undergoing a lengthy operation or those with difficulty lying flat [3].

One advantage of ISBCS is that it avoids suboptimum visual acuity between surgeries as both cataracts are removed in one sitting [11]. Of the participants that gave reasons in favour of ISBCS, 30% of surgery-naive participants and 17% of post-operative participants would undergo ISBCS to improve their eyesight more quickly. The higher rates amongst surgery-naive participants may represent a greater eagerness of patients with visually significant cataracts to restore their quality of life via ISBCS.

Anisometropia is often experienced between surgeries in DSBCS [11]. Of the respondents in favour of ISBCS, 12.1% of surgery-naive participants and 37.0% of post-operative participants reported that they would choose ISBCS to avoid issues associated with visual imbalance. In addition, 4.3% of the responses given by post-operative participants in favour of ISBCS mentioned the avoided expense of additional spectacles or a blank spectacle lens. The three-fold higher proportion of post-operative participants that cited difficulties related to anisometropia suggests that, although this is an important motivator for patients choosing ISBCS, patients only become aware of these issues after undergoing cataract surgery. Given that certain patients, such as high myopes and hyperopes, are at particular risk of anisometropia during DSBCS, this should be a consideration when counselling these patients.

Concerns related to the ISBCS recovery period were a common barrier to uptake. Amongst respondents that reported reasons against choosing ISBCS, around a third (34%) mentioned concerns regarding coping with visual impairment in both eyes while eyes recover. While this is understandable and some degree of additional support may be required in the immediate hours after surgery, the implicit worry that ISBCS will leave patients debilitated for long periods of time is not substantiated. As demonstrated by the quotes given by the post-operative ISBCS patients in Fig. 1, recovery of visual function following ISBCS can be very quick, which is often unexpected by patients.

Another common misunderstanding amongst participants regarding the ISBCS recovery period was the need to wear patches that obscure both eyes. It is likely that this misunderstanding has arisen as post-operative patients sometimes wear opaque dressings following unilateral cataract surgery with sub-tenons anaesthesia. Although the fear of wearing patches on both eyes following ISBCS is reasonable, as this would leave participants with no visual perception, it is avoided in ISBCS, as patients have topical anaesthesia and clear shields placed after surgery.

Given that the mean age of the study population is over 70 years, it is unsurprising that a majority (67.8%) reported to be retired. This may explain why relatively few (9%) of the participants would choose ISBCS to reduce time off work. Overall, there was no significant statistical difference (p = 0.62) found in employment status between participants that would and would not undergo ISBCS. While this is perhaps unexpected due to the emphasis placed on lost worktime in prior ISBCS economic analysis, this is consistent with previous patient attitude surveys [5, 6, 13].

Cataract service delays were a common concern during the pandemic [22]. Although we are moving into a post-COVID-19 era and services are catching up, a residual cataract backlog exists and the demand for cataract surgery continues to grow [1, 2]. Since ISBCS is known to improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of cataract services, increasing its practice would offer significant benefits [4,5,6]. This is reflected in the responses given by participants in favour of ISBCS with over a quarter (28%) reporting that they would opt for ISBCS to reduce the wait for surgery and 9% reporting that ISBCS would benefit the NHS. Although the desire to undergo ISBCS to reduce waiting time may be exaggerated in our study due to COVID-19 related delays, the need to reduce waiting lists and optimise services remains of paramount importance to ensure the sustainability of NHS cataract services.

This cross-sectional study suggests that significantly more NHS cataract patients would opt for ISBCS if given the choice. Given the need for more efficient NHS cataract services, this is promising, and suggests that service redesign proposals to increase the practice of ISBCS are possible. However, for this to be realised in clinical practice, patient barriers to uptake of ISBCS, such as misunderstandings about the recovery period, must first be addressed. In addition, our data suggests that ophthalmic surgeons and clinic staff have substantial influence in facilitating patients to undergo ISBCS, both as sources of information about the surgery and as counsellors in clinic. Thus, it may be that patients will only be offered and accept ISBCS at scale once ophthalmic surgeons become convinced that ISBCS is in their patients’ best interests.

Summary

What was known before

-

ISBCS is recommended by NICE [NG77] for consideration of offering to the majority of cataract patients.

-

Fewer than 1% of cataract operations performed in the NHS were ISBCS in 2018/19.

-

A survey undertaken at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic found that 45% of patients on NHS cataract surgery waiting lists would opt for ISBCS if offered it.

What this study adds

-

As the post-pandemic recovery continues, ISBCS may have a role to play with over a third of bilateral cataract patients indicating that they would opt for ISBCS if given a choice.

-

Less than half of cataract patients are aware that ISBCS is an option, and eye clinic staff were the main reported source of information for those who were aware of it.

-

Patient misunderstandings and surgeon preferences are common barriers to patients undergoing ISBCS in the NHS.

Data availability

The data generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Buchan JC, Norman P, Shickle D, Cassels-Brown A, MacEwen C. Failing to plan and planning to fail. Can we predict the future growth of demand on UK Eye Care Services? Eye 2019;33:1029–31.

Lin P-F, Naveed H, Eleftheriadou M, Purbrick R, Zarei Ghanavati M, Liu C. Cataract service redesign in the post-COVID-19 era. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;105:745–50.

Buchan JC, Donachie PHJ, Cassels-Brown A, Liu C, Pyott A, Yip JLY, et al. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Ophthalmology Database study of cataract surgery: Report 7, immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery in the UK: Current practice and patient selection. Eye 2020;34:1866–74.

O’Brart DP, Roberts H, Naderi K, Gormley J. Economic modelling of immediately sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS) in the National Health Service based on possible improvements in surgical efficiency. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020;5:e000426.

Leivo T, Sarikkola A-U, Uusitalo RJ, Hellstedt T, Ess S-L, Kivelä T. Simultaneous bilateral cataract surgery: economic analysis; Helsinki Simultaneous Bilateral Cataract Surgery Study Report 2. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:1003–8.

O’Brien JJ, Gonder J, Botz C, Chow KY, Arshinoff SA. Immediately sequential bilateral cataract surgery versus delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery: Potential hospital cost savings. Can J Ophthalmol. 2010;45:596–601.

Lee E, Balasingam B, Mills EC, Zarei-Ghanavati M, Liu C. A survey exploring ophthalmologists’ attitudes and beliefs in performing Immediately Sequential Bilateral Cataract Surgery in the United Kingdom. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20:210.

Sarikkola A-U, Uusitalo RJ, Hellstedt T, Ess S-L, Leivo T, Kivelä T. Simultaneous bilateral versus sequential bilateral cataract surgery: Helsinki Simultaneous Bilateral Cataract Surgery Study Report 1. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:992–1002.

Serrano-Aguilar P, Ramallo-Fariña Y, Cabrera-Hernández JM, Perez-Silguero D, Perez-Silguero MA, Henríquez-De La FeF, et al. Immediately sequential versus delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery: Safety and effectiveness. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1734–42.

Arshinoff SA, Bastianelli PA. Incidence of postoperative endophthalmitis after immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:2105–14.

Lundström M, Albrecht S, Nilsson M, Åström B. Benefit to patients of bilateral same-day cataract extraction: randomized clinical study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:826–30.

Naderi K, Maubon L, Jameel A, Patel DS, Gormley J, Shah V, et al. Attitudes to cataract surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: a patient survey. Eye 2020;34:2161–2.

Shah V, Naderi K, Maubon L, Jameel A, Patel DS, Gormley J, et al. Acceptability of immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS) in a public health care setting before and after COVID-19: A prospective patient questionnaire survey. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020;5:e000554.

Wang H, Ramjiani V, Raynor M, Tan J Practice of immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS) since COVID-19: a patient and surgeon survey. Eye. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01521-1.

Carolan JA, Amsden LB, Lin A, Shorstein N, Herrinton LJ, Liu L, et al. Patient experience and satisfaction with immediate sequential and delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2021.09.016.

Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 1932;22:55.

Cataracts in adults: management 2017. NICE guideline [NG77]. 2017. https://www.niceorguk/guidance/ng77.

Day AC, Donachie PHJ, Sparrow JM, Johnston RL. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Ophthalmology Database study of cataract surgery: Report 1, visual outcomes and complications. Eye 2015;29:552–60.

Rolison JJ, Hanoch Y, Wood S, Liu PJ. Risk-taking differences across the adult life span: a question of age and domain. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69:870–80.

Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Patient information: Cataract. 2020. https://www.moorfields.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/Cataract%20service_1.pdf.

Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Alexeeff S, Carolan J, Shorstein NH. Immediate sequential vs. delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery: retrospective comparison of postoperative visual outcomes. Ophthalmology 2017;124:1126–35.

Sii SSZ, Chean CS, Sandland-Taylor LE, Anuforom U, Patel D, Le GT, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cataract surgery- patients’ perceptions while waiting for cataract surgery and their willingness to attend hospital for cataract surgery during the easing of lockdown period. Eye 2020;35:3156–8.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceptualised study and designed questionnaire. JM, CL, and AD contributed to data collection. JM conducted data analysis and produced draft and final manuscript. JB revised draft manuscript. Final manuscript reviewed and commented on by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malcolm, J., Leak, C., Day, A.C. et al. Immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery: patient perceptions and preferences. Eye 37, 1509–1514 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02171-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02171-7