Abstract

Objectives

To study the patterns of vitreous incarceration in sutured vs non-sutured sclerotomies in patients subjected to 25-gauge macular surgery.

Methods

A prospective study of 135 eyes affected by epiretinal membrane or macular hole. Vitreal disposition was evaluated via ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) at the sclerotomy sites between 30 and 40 days after surgery, once the tamponade had completely disappeared.

Results

In total, 349 sclerotomies (86.2%) of 99 patients were non-sutured while 56 sclerotomies (13.8%) of 36 patients were sutured at the end of the surgical procedure. Among the 36 patients with sutured sclerotomies, 15 out of 36 (41.6%) had at least two sclerotomies sutured. All the sclerotomy sites were evaluated (405 sclerotomies). Sclerotomy suture was significantly associated with a less aggressive pattern of vitreal incarceration (OR: 0.16, 95% CI: 0.07–0.35, p < 0.001). Compared to preoperative values, day 1 post operative IOP was not significantly different in patients with sutured sclerotomies, while patients with non-sutured sclerotomies had a significantly lower day 1 post operative IOP.

Conclusions

In 25-gauge macular surgery, UBM evaluation documented a higher rate of postoperative vitreous incarceration in the non-sutured sclerotomies, confirming the previously postulated role of the residual vitreous, left at the end of the surgery, in closing the sclerotomy site.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the era of sutureless small-gauge pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) the competency of sclerotomy sites has been the subject of intensive study. A leaking sclerotomy, either clinically or subclinically, may cause postoperative hypotony and endophthalmitis [1]. Time-saving methods for the closure of a leaking sclerotomy, as alternatives to suturing, have been analysed in both humans (bipolar diathermy, tissue adhesives, releasable sutures) and in animals (scleral hydration) [2,3,4,5]. Preoperative diagnosis, reoperation, intraoperative lens status, cannula gauge, incision architecture, and the absence of tamponade have all been shown to represent risk factors for leakage. In the abovementioned studies, vitreous base dissection has been postulated as an additional risk factor for sclerotomy incompetence, under the hypothesis that the residual vitreous remaining at the end of surgery may plug the sclerotomy. However, in none of these studies was visualisation of the vitreous at the sclerotomy site documented [6,7,8,9,10].

Assessment of vitreal incarceration at the sclerotomy site can be performed through anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT), ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM), and direct visualisation [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In 20-gauge PPV in humans, Sabti et al. [23] showed via UBM that a higher rate of vitreous shaving around the sclerotomy site is related to a lower rate of vitreous incarceration. However, Li et al. [24] suggested, also via UBM, that the wound-healing process of sclerotomies after 25-gauge PPV appears different from that after conventional 20-gauge PPV. In small-gauge PPV, the studies using UBM or direct visualisation of vitreous incarceration at the sclerotomy site show no correlation, when evaluated, between vitreous incarceration and sclerotomy leakage or need for suturing [17,18,19,20,21,22]. In animals, Benitez-Herreros et al. showed that the cannula extraction technique and the vitrectomy degree in different areas of the vitreous cavity were related to the amount of vitreous incarceration and, in contrast to what has been found in humans, to bleb formation, thus confirming the role of vitreous remnants in plugging the sclerotomy site and advocating additional studies in humans [25,26,27].

In a recent study we evaluated vitreous incarceration at the sclerotomy site using UBM, in patients subjected to valved 23-, 25-, or 27-gauge and non-valved 23- or 25-gauge macular surgery, documenting no differences in postoperative patterns. Although not the purpose of the study and probably due to the relatively low number of sclerotomies analysed, all of them being non-sutured, we failed to show a prevalence of one vitreal pattern over the others in any of the valved or non-valved subgroups [28].

In the present study we aim to analyse postoperative vitreal patterns using UBM, again after macular surgery alone, but in a higher number of patients undergoing only 25-gauge surgery and including both non-sutured and sutured sclerotomies. This study may be of interest to verify what has been hypothesised by many, and in consideration of the still-present risk of rhegmatogenous postoperative complications after macular surgery, as the role of perisclerotomy vitreous incarceration in determining postoperative retinal breaks is well-known [29].

Materials and methods

Subjects

This prospective study included 135 eyes of 135 patients. The inclusion criteria were: being affected by idiopathic epiretinal membrane (ERM) or macular hole (MH), and being subjected to primary 25-gauge PPV without intraocular complications, between June 2018 and September 2019 at the Ophthalmology Section of the Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, University of Siena, Siena, Italy. Only ERMs and MHs were included in order to render the study population homogenous, in terms of both vitreal characteristics and length of surgery. The exclusion criteria were: coexisting ocular disorders, except cataract; patients requiring PPV for indications other than those mentioned above; patients previously subjected to intraocular surgery, except cataract surgery; and patients with no identifiable sclerotomy site at slit-lamp examination. The research adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the institutional review board approved the study. Patients were treated after being informed of the nature of the treatment being offered, its potential risks, benefits, adverse effects, possible outcomes, and after having signed a consent form.

Each patient underwent a complete preoperative evaluation. The presence or absence of posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) was defined by biomicroscopic observation using a 90-dioptre lens, OCT examination, and B-scan ultrasound. All patients underwent OCT evaluation of the macular disorder.

Surgical technique

All patients underwent 25-gauge PPV performed by the same surgeon (GMT). The sclerotomy sites were located in the inferotemporal, superotemporal and superonasal quadrants. The conjunctiva was anteriorly displaced away from the intended sclerotomy site with forceps, in order to purposefully misalign the conjunctival and scleral incisions. The trocars, all valved and from the same company (Alcon Laboratories Inc., Fort Worth, TX), were inserted 3.5 mm from the corneoscleral limbus in both phakic and pseudophakic eyes, at an angle of ~30° parallel to the limbus. Once past the trocar sleeve, the angle was changed to be perpendicular to the surface and the cannula was inserted into the eye. The cannula was held in place with forceps and the trocar was removed. The endoilluminator and the vitrector were placed through the superior sites. PPV was performed using the Constellation vitrectomy instrument (Alcon Laboratories Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) in order to remove all the vitreous visible without scleral indentation using a non-contact panoramic viewing system (RESIGHT 700, Carl Zeiss Meditec, AG). In the absence of PVD, it was induced with the vitrectomy probe in the “cutter-off” mode placed over the optic disc. ERM and internal limiting membrane peeling were performed using either triamcinolone, indocyanine green or Brilliant Peel (Fluoron GmbH, Ulm, Germany). Fluid/air exchange was performed in every patient. In ERM cases the eye was left filled with air, while air was substituted with 8% C3F8 in the MH cases. At the end of the procedure, the cannulas were removed by slowly pulling them out, following the angled entry path. Pressure was applied to the sclerotomy sites with a cotton-tip applicator to enhance sclerotomy sealing and to return the displaced conjunctiva to its original position. The scleral ports were never hydrated. A single stitch of 9–0 vicryl was applied to a sclerotomy site in the case of air or gas leakage persisting despite two sessions of 15-s compression on the sclerotomy site.

Postoperative examination

Patients were subjected to a complete ophthalmological evaluation the day after surgery and in the subsequent follow-up visits.

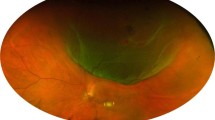

UBM was performed at the sclerotomy sites between 30 and 40 days after surgery, once the tamponade had completely disappeared. To avoid bias, the ultrasonographer (AM) was masked to the patient grouping and diagnosis. To identify the precise sclerotomy location, the patients were examined by slit lamp (small black dot on the sclera and/or presence of converging episcleral vessels) and the sclerotomy site was marked with a sterile surgical marking pen. UBM examination was performed using a high frequency transducer (50 MHz) (Aviso S, Quantel Medical, Clermont-Ferrand, France) with the probe oriented both radially and tangentially to the limbus in order to intersect and detect the entire sclerotomy tract, as previously described [28]. We found three patterns of vitreous/sclerotomy relationships, classified as: P0 (vitreous not visible or vitreous strand distant from the sclerotomy site) (Fig. 1a); P1 (vitreous strand parallel to and in contact with the sclerotomy site) (Fig. 1b); and P2 (vitreous strand entrapped in the sclerotomy site) (Fig. 1c) [28].

Statistical analysis

Multi-level models were used to investigate the effect of covariates on the vitreous incarceration pattern, with individuals as random effects to account for the correlated nature of measurements at multiple sclerotomy sites. Due to the ordinal nature of the response variable, ordinal logistic regression was used and the odds ratio (OR) of a higher level of incarceration was obtained.

The Mann–Whitney and Fisher’s test were used to investigate differences between patients receiving vs not receiving at least one sclerotomy suture.

The statistical significance level for all univariate analyses was always set to 95% (p < 0.05).

All statistical computations were performed using Stata 14.1 statistical packages (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

Three-hundred and forty-nine sclerotomies (86.2%) of 99 patients were non-sutured while 56 sclerotomies (13.8%) of 36 patients were sutured at the end of the surgical procedure (Fig. 2). Among the 36 patients with sutured sclerotomies, 15 out of 36 (41.6%) had at least two sclerotomies sutured. All sclerotomy sites were evaluated (405 sclerotomies) via UBM. No differences were present in the clinical characteristics of patients requiring suture compared to those not requiring suture (Table 1). No 9.0 vicryl suture remnants were identified by slit-lamp at the time of UBM analysis performed between 30 and 40 days after surgery. Intrascleral suture remnants, if present, never affected the visualisation of the internal side of the sclerotomy site [19, 30].

Table 2 presents the effects of all study variables on vitreous incarceration. Sclerotomy suture was the only factor significantly associated with the less aggressive pattern of vitreal incarceration (P0) (OR: 0.16, 95% CI: 0.07–0.35, p < 0.001). Among other covariates, only the sclerotomy site was associated with a vitreous incarceration pattern (p < 0.001). Specifically, the superonasal site showed lower levels of vitreous incarceration than the inferotemporal site (OR: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.14–0.45) and the superotemporal site (OR: 0.32, 95% CI: 0.18–0.58, p < 0.001); the superotemporal site did not differ from the inferotemporal site (OR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.44–1.35, p = 0.366).

The superonasal sclerotomy site, which appeared less frequently associated with vitreous incarceration, was also the most sutured among the three: specifically, sclerotomies were more commonly sutured at the superonasal site (22; 39.3%) compared to the inferotemporal (16; 28.6%) and superotemporal (18; 32.1%) sites, although this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.408). However, the effect of the sclerotomy site on vitreous incarceration was independent from that of suture in the multivariate analysis (test for interaction: p = 0.437). We investigated whether the differences in vitreous incarceration among sclerotomy sites were influenced by laterality (right vs left eye). We found no significant interaction between site and laterality (p = 0.196) in multivariable regression analyses, a result which was robust to adjustment with suture effect.

No differences were found between non-sutured and sutured sclerotomy patients in relation to preoperative intraocular pressure (IOP). No patients experienced postoperative hypotony, defined as IOP ≤ 5 mmHg. Compared to the preoperative values, in sutured sclerotomies patients’ IOP was no different at postoperative day 1 (p = 0.09), 7 (p = 0.2) or 30 (p = 0.09). In non-sutured sclerotomy patients, compared to the preoperative values, IOP was no different at postoperative day 7 (p = 0.07) or 30 (p = 0.06) but it was significantly lower at postoperative day 1 (p < 0.0001). No rhegmatogenous complications were found in any patients after at least 4 months of follow-up.

Discussion

Although widely hypothesised, the role of the residual vitreous left at the end of a vitrectomy procedure in plugging the sclerotomy has not been confirmed in humans, nor has its disposition in sutured vs non-sutured sclerotomies been analysed [6,7,8,9,10, 31]. Herein, we document for the first time the role of the vitreous left at the end of the surgery in plugging the sclerotomy.

In their evaluation of the risk factors associated with sclerotomy leakage and postoperative hypotony in 23-gauge PPV, Woo et al. [31] analysed two surgical groups of patients, differing in their indications for surgery, based on the extent of vitreous removal: a vitreous base remnant group compared to a vitreous base dissection group. Vitreous base dissection was shown to be a risk factor for leakage—less vitreous, less plugging effect. However, the lack of competency could also have been attributed, as stated by the Authors, to the prolonged stretching of the sclerotomy incision in order to reach the vitreous base, as well as to longer surgery, causing prolonged tissue fatigue which in turn may cause wound gape. Additionally, we cannot exclude the different diagnoses at entry and, consequently, the results could have been influenced by the patients’ different vitreal characteristics (the vitreous base dissection group included vitreous haemorrhage, rhegmatogenous and tractional retinal detachment, while the vitreous remnant group was composed of macular diseases). The same reasoning can be followed for the studies that have identified previous vitrectomy as a risk factor for sclerotomy leakage [7, 8]. In fact, while on the one hand leakage after reoperation can be attributed to a reduced residual vitreous due to more complete vitreous removal—less vitreous, less plugging effect—we cannot exclude that concomitant scleral alterations following the previous surgery may have caused a reduction in the competence of the sclerotomies themselves. Additionally, in none of the abovementioned studies was visualisation of the vitreous at the sclerotomy site documented.

With reference to the studies documenting the extent of vitreous incarceration at the sclerotomy site via UBM or direct visualisation (endoscopy), these show no correlation (when evaluated) between vitreous incarceration and sclerotomy leakage or the need for suturing [17,18,19,20,21,22]. Napgal et al. [21] analysed the dynamics of the port during closure through endoscopy in 20 sclerotomies of 10 patients undergoing small-gauge surgery for vitreous haemorrhage, usually following proliferating diabetic retinopathy: they documented an increased clogging effect in small-gauge surgery compared to 20-gauge surgery. Also using endoscopy, Inoue et al. [22] visualised vitreous incarceration in two patients operated on with 25-gauge PPV for ERM, documenting vitreous incarceration despite the removal of the peripheral vitreous. Using UBM, Texeira et al. [18] did not document any vitreous incarceration after 23-gauge surgery performed for different indications. Avitabile at al. [20] documented, also using UBM, an incarceration rate equal to 80% after 25-gauge surgery, without correlating it with any leakage of the sclerotomies themselves. Gutfleisch et al. [19] evaluated vitreous incarceration in patients undergoing small-gauge surgery for different indications by analysing only one sclerotomy per patient via UBM. They documented increased vitreous incarceration in the 10 patients subjected to 25-gauge surgery: this, surprisingly, was associated with an increased rate of conjunctival bleb formation. Also using UBM, Lopez-Guajardo et al. [17] documented a 72% incarceration rate in 53 sclerotomies analysed after 25-gauge surgery, without finding a correlation with postoperative conjunctival bleb formation.

In animals, Benitez-Herreros et al. documented that the vitrectomy degree in different areas of the vitreous cavity was related to the amount of vitreous incarceration and to bleb formation, the latter in contrast to what has been found in humans, thus confirming the role of vitreous remnants in plugging the sclerotomy site and advocating additional studies in humans [26, 27].

In the present study, we analysed the vitreal disposition in 405 sclerotomy sites via UBM between 30 and 40 days after surgery, once the tamponade had completely disappeared. As previously shown, three vitreal patterns were identified: P0 (vitreous not visible or vitreous strand distant from sclerotomy site), P1 (vitreous strand parallel to and in contact with sclerotomy site), and P2 (vitreous strand entrapped in sclerotomy site) [28]. In total, 349 sclerotomies (86.2%) of 99 patients were non-sutured while 56 sclerotomies (13.8%) of 36 patients were sutured at the end of the surgical procedure. Sclerotomy suture was significantly associated with the less aggressive pattern of vitreal incarceration (P0), thus confirming the plugging effect of the residual vitreous in closing a self-sealing sclerotomy, as has been hypothesised by many Authors. In this light, since the entity of vitreous removal in each single eye is, in our experience, usually homogenous in the different quadrants of the vitreous body, we would have expected that the eyes that needed suturing in one sclerotomy would have needed suturing in the others too, if the role of the residual vitreous was to close them. In fact, among the 36 patients with sutured sclerotomies, 15 out of 36 (41.6%) had at least two sclerotomies sutured. Of the patients with sutured and non-sutured sclerotomies, no eye presented hypotony, nor were any differences in IOP found between preoperative and postoperative values at 7 and 30 days. However, on the first postoperative day, the eyes with self-sealing sclerotomies had significantly lower IOP than the preoperative values, while those with sutured sclerotomies showed no difference compared to the preoperative values. This confirms the possibility that even when the sclerotomy is competent at the end of the intervention, without the need for suturing, a subclinical leak may occur postoperatively [2, 31].

According to the present results, certain considerations regarding possible changes in the surgical technique can be made, with the aim of maintaining the competency of the self-sealing sclerotomy on the one hand, and reducing the potential risk of iatrogenic retinal breaks and rhegmatogenous retinal detachments linked to vitreous incarceration on the other. In fact, rhegmatogenous complications, although not reported in any of the patients in the present series, do still occur and can have a devastating effect, as recently reported by Parke and Lum, who showed a 2–2.5% rate of retinal detachment in the first year after MH and macular pucker surgery [29]. In this light, in macular surgery the surgeon’s goal could be to achieve maximal vitreous removal without indentation, at least at the sclerotomy site, in order to intentionally leave a minimal but sufficient quantity of peripheral vitreous skirt in order to plug the sclerotomy. In our practice, the attempt to achieve maximal vitreous removal is already ongoing and could explain the relatively high rate of suturing (13.8%) experienced in the present series, especially in consideration of the fact that the tamponade with air or gas, performed in every patient in this series, should favour the competency of the sclerotomy [31, 32]. Additionally, if our results could be applied to other clinical scenarios which require more aggressive vitreous base dissection—i.e., rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in high myopia—the surgeon may opt to intentionally leave a residual skirt of vitreous around the infusion line in order to avoid eye collapse at the end of the surgery.

Our results seem to be reliable, since the population under study was homogenous, being composed of only ERMs and MHs, also in terms of vitreal characteristics, length of surgery, and the tamponade used at the end of the surgery. Moreover, UBM was performed in all patients between 30 and 40 days after surgery, once the tamponade had completely disappeared. Additionally, no difference in relation to intraoperative manoeuvres that have previously been shown to be associated with vitreal incarceration was present. In particular, Benitez-Herreros et al. [25] found that cannula extraction with the light probe inserted reduced the amount of vitreous incarceration. In this respect, cannula extraction was performed without pulling the vitreous inside the eye in any of our patients. Even analysis of the clinical characteristics of the patients requiring suture compared to those not requiring suture did not reveal differences in terms of age, male/female, ERM/MH, and air/gas ratios, or PVD at entry.

A limitation of the present study is that, due to safety reasons, the UBM analysis was performed not at the end of the surgical procedure but between 30 and 40 days afterwards, and we cannot exclude different results right at the end of the surgery. Anterior segment OCT could have been used in the first postoperative days, although OCT may miss vitreous incarceration due to an insufficient signal and the tamponade could have impacted the results. However, Lopez-Guajardo et al. [11] clearly stated that no changes in the vitreous entrapment rate are expected in the first months after vitrectomy. Additionally, the number of the sutured sclerotomies in our study is not high, notwithstanding the strict indication for suturing, due our low tolerance for leakage. However, sclerotomies subjected to suturing are the minority in every-day surgical practice and not easy to find.

Herein, our UBM evaluation documents a higher rate of postoperative vitreous incarceration in non-sutured sclerotomies in macular surgery. This is of importance to definitely recognise the role of the residual vitreous left at the end of the surgery in closing the sclerotomy site and to possibly prompt small changes in the extent of vitreous removal with the aim of intentionally achieving a balance between the maintenance of the incision’s self-sealing characteristics and the focus on avoiding postoperative rhegmatogenous complications.

Summary

What was known before

-

A leaking sclerotomy may cause postoperative hypotony and endophthalmitis.

-

Scleral suturing is the most frequent method to seal leaking sclerotomy sites, but it is time-consuming, may be difficult to perform in thin scleras and can cause discomfort and postoperative astigmatism.

-

The residual vitreous left at the end of a vitrectomy procedure was hypothesised, but not demonstrated, to have a role in plugging the scleral wound and promoting the self-sealing of sclerotomies.

-

Perisclerotomy vitreous incarceration can increase the risk of rhegmatogenous postoperative complications.

What this study adds

-

A higher rate of postoperative vitreous incarceration in non-sutured sclerotomies in macular surgery is documented.

-

The role of the residual vitreous in plugging sclerotomies after vitrectomy and its association with scleral suturing are demonstrated here, for the first time, in a clinical setting via UBM.

-

Small changes in the extent of vitreous removal can be considered by surgeons, with the aim of intentionally achieving a balance between the maintenance of the incision self-sealing characteristics and the focus on avoiding postoperative rhegmatogenous complications.

References

Benitez-Herreros J, Lopez-Guajardo L, Camara-Gonzalez C, Perez-Crespo A, Silva-Mato A, Alvaro-Meca A, et al. Influence of incisional vitreous incarceration in sclerotomy closure competency after transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:4366–71.

Reibaldi M, Longo A, Reibaldi A, Avitabile T, Pulvirenti A, Lippolis G, et al. Diathermy of leaking sclerotomies after 23-gauge transconjunctival pars plana vitrectomy: a prospective study. Retina. 2013;33:939–45.

Benitez-Herreros J, Lopez-Guajardo L, Vazquez-Blanco M, Perez-Crespo A, Silva-Mato A. Assessment of closure competency of sutureless vitrectomy sclerotomies after scleral hydration. Curr Eye Res. 2015;22:1–4.

López-Guajardo L, Benítez-Herreros J, Donate-López J, Opazo-Toro V. Evaluation of leakage resistance improvement in transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy sclerotomies closed with adhesives. an experimental study. Eye. 2020;34:1229–34.

Rizzo S, Pacini B, De Angelis L, Barca F, Savastano A, Giansanti F, et al. Intrascleral hydration for 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy sclerotomy closure. Retina. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000002703.

Singh RP, Bando H, Brasil OF, Williams DR, Kaiser PK. Evaluation of wound closure using different incision techniques with 23-gauge and 25-gauge microincision vitrectomy systems. Retina. 2008;28:242–8.

Lin AL, Ghate DA, Robertson ZM, O’Sullivan PS, May WL, Chen CJ. Factors affecting wound leakage in 23-gauge sutureless pars plana vitrectomy. Retina. 2011;31:1101–8.

Bamonte G, Mura M, Stevie Tan H. Hypotony after 25-gauge vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:156–60.

Gupta OP, Maguire JI, Eagle RC Jr, Garg SJ, Gonye GE. The competency of pars plana vitrectomy incisions: a comparative histologic and spectrophotometric analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:243–50.e1.

Lopez-Guajardo L, Benitez-Herreros J, Silva-Mato A. Experimental model to evaluate mechanical closure resistance of sutureless vitrectomy sclerotomies using pig eyes. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:4080–4.

Lopez-Guajardo L, Benitez-Herreros J, Camara-Gonzalez C, Silva-Mato A. Assessment of vitreous incarceration in sclerotomies with OCT, ultrasound biomicroscopy, and direct visualization. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2012;43:S117–22.

Taban M, Sharma S, Ventura AA, Kaiser PK. Evaluation of wound closure in oblique 23-gauge sutureless sclerotomies with Visante optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:101–7.

Taban M, Ventura AA, Sharma S, Kaiser PK. Dynamic evaluation of sutureless vitrectomy wounds: an optical coherence tomography and histopathology study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:2221–8.

Chen D, Lian Y, Cui L, Lu F, Ke Z, Song Z. Sutureless vitrectomy incision architecture in the immediate postoperative period evaluated in vivo using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2003–9.

López-Guajardo L, Benítez-Herreros J. Vitreous incarceration in sclerotomies. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:204–5.

López-Guajardo L, Benitez-Herreros J, Teus-Guezala M. Optical coherence tomography as a method for studying sutureless microincisional vitrectomy sclerotomies. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:321–2.

López-Guajardo L, Vleming-Pinilla E, Pareja-Esteban J, Teus-Guezala MA. Ultrasound biomicroscopy study of direct and oblique 25-gauge vitrectomy sclerotomies. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:881–3.

Teixeira A, Allemann N, Yamada AC, Uno F, Maia A, Bonomo PP. Ultrasound biomicroscopy in recently postoperative 23-gauge transconjunctival vitrectomy sutureless self-sealing sclerotomy. Retina. 2009;29:1305–9.

Gutfleisch M, Dietzel M, Heimes B, Spital G, Pauleikhoff D, Lommatzsch A. Ultrasound biomicroscopic findings of conventional and sutureless sclerotomy sites after 20-, 23-, and 25-G pars plana vitrectomy. Eye. 2010;24:1268–72.

Avitabile T, Castiglione F, Bonfiglio V, Castiglione F. Transconjunctival sutureless 25-gauge versus 20-gauge standard vitrectomy: correlation between corneal topography and ultrasound biomicroscopy measurements of sclerotomy sites. Cornea. 2010;29:19–25.

Nagpal M, Wartikar S, Nagpal K. Comparison of clinical outcomes and wound dynamics of sclerotomy ports of 20, 25, and 23 gauge vitrectomy. Retina. 2009;29:225–31.

Inoue M, Ota I, Taniuchi S, Nagamoto T, Miyake K, Hirakata A. Miyake-Apple view of inner side of sclerotomy during microincision vitrectomy surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:e412–6.

Sabti K, Kapusta M, Mansour M, Overbury O, Chow D. Ultrasound biomicroscopy of sclerotomy sites: the effect of vitreous shaving around sclerotomy sites during pars plana vitrectomy. Retina. 2001;21:464–8.

Li KK, Tam BS, Lam SW, Chan WM, Lam DS. 25-gauge vitrectomy. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:888–9.

Benitez-Herreros J, Lopez-Guajardo L, Camara-Gonzalez C, Silva-Mato A. Influence of the interposition of a non-hollow probe during cannula extraction on sclerotomy vitreous incarceration in sutureless vitrectomy. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:7322–6.

Benitez-Herreros J, Lopez-Guajardo L, Camara-Gonzalez C, Perez-Crespo A, Vazquez-Blanco M, Silva-Mato A. Influence of the source of incisional vitreous incarceration on sclerotomy closure competency after transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39:1194–9.

Benitez-Herreros J, Lopez-Guajardo L, Camara-Gonzalez C, Perez-Crespo A, Silva-Mato A, Alvaro-Meca A, et al. Evaluation of conjunctival bleb detection after vitrectomy by ultrasound biomicroscopy, optical coherence tomography and direct visualization. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39:390–4.

Tosi GM, Malandrini A, Cevenini G, Neri G, Marigliani D, Cerruto A, et al. Vitreous incarceration in sclerotomies after valved 23-, 25-, or 27-gauge and non valved 23- or 25-gauge macular surgery. Retina. 2017;37:1948–55.

Parke DW 3rd, Lum F. Return to the operating room after macular surgery: IRIS registry analysis. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:1273–8.

Kwok AK, Tham CC, Loo AV, Fan DS, Lam DS. Ultrasound biomicroscopy of conventional and sutureless pars plana sclerotomies: a comparative and longitudinal study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:172–7.

Woo SJ, Park KH, Hwang JM, Kim JH, Yu YS, Chung H. Risk factors associated with sclerotomy leakage and postoperative hypotony after 23-gauge transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy. Retina. 2009;29:456–63.

Khan MA, Kuley A, Riemann CD, Berrocal MH, Lakhanpal RR, Hsu J, et al. Long-term visual outcomes and safety profile of 27-gauge pars plana vitrectomy for posterior segment disease. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:423–31.

Funding

The study was partially supported by the I.Ri.Fo.R Onlus (Institute for Research, Training and Rehabilitation), Italian Union of Blind and Visually Impaired People.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tosi, G.M., Malandrini, A., Bacci, T. et al. Vitreous incarceration in sutured vs non-sutured sclerotomies after 25-gauge macular surgery. Eye 35, 2246–2253 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01234-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01234-x