Abstract

Non-invasive prenatal testing’s (NIPT) potential to screen for a wide range of conditions is receiving growing attention. This study explores Canadian healthcare professionals’ perceptions towards NIPT’s current and possible future uses, including paternity testing, sex determination, and fetal whole genome sequencing. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten healthcare professionals, and another 184 participated in a survey. The triangulation of our findings shows that there is considerable agreement among healthcare professionals on expanding NIPT use for medical conditions including fetal aneuploidies and monogenic diseases, but not for non-medical conditions (sex determination for non-medical reasons and paternity testing), nor for risk predisposition information (late onset diseases and Fetal Whole Genome Sequencing). Healthcare professionals raise concerns related to eugenics, the future child’s privacy, and psychological and emotional burdens to prospective parents. Professional societies need to take these concerns into account when educating healthcare professionals on the uses of NIPT to ensure prospective parents’ reproductive decisions are optimal for them and their families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) is a screening technology analysing cell-free fetal DNA originating from the placenta and circulating in maternal blood. The analysis can be performed as early as the 9th week of pregnancy and can detect trisomies 21, 13, and 18 more accurately than previously existing prenatal screening tests such as maternal serum screening (MSS) [1, 2]. Although NIPT’s sensitivity for trisomy 21 (Down syndrome, DS) is reported in the literature as 99.9% (with 98% specificity), it remains a screening test and not a diagnostic test, such as amniocentesis [3]. Nevertheless, NIPT’s increased accuracy means that fewer women with false positive results are unnecessarily undergoing amniocentesis and subjecting themselves to the risk of miscarriage.

The fact that NIPT can be performed earlier in the pregnancy than other screening tests means that parents get more time to make decisions about their pregnancy. However, it is precisely the clinical advantages of NIPT that may lead to an exacerbation of the ethical issues that prenatal screening raises [4]. For instance, the literature raises concerns that NIPT’s routinization—its increased inclusion in routine prenatal care practices—could lead to further erosion of informed consent, trivialisation of pregnancy termination, and discrimination against people with disabilities.

NIPT could allow for more genetic conditions to be detected than the ones commonly screened for now [5]. Given the scientific work conducted with the aim of expanding the list of conditions that NIPT screens for, one would expect a burgeoning literature on what the main stakeholders think about such potential future uses of NIPT. Indeed, there has been empirical work conducted with pregnant women [6], but very little insight exists into healthcare professionals’ (HCPs) views [7]. Kater-Kuipers et al. have conducted an interesting study that included interviews with professionals in the field of prenatal screening in the Netherlands with the aim of presenting ‘ethical guidance for the expansion of the scope of prenatal screening’ [8]. The authors conclude that four moral limits ought to ‘demarcate a responsible expansion of the scope of NIPT’: (1) particular attention to truly informed consent in genetic counseling; (2) proportionate expansion (‘test should be clinically valid and useful to women’); (3) respect for the right of the prospective child to an open future; and (4) just distribution of health resources. To gain more insights about HCPs’ views with regards to NIPT expansion and these four moral limits, we conducted interviews with ten HCPs and a survey of 184 HCPs, all from Canada.

As the studies were conducted between 2014 and 2016, a brief note is warranted on how the offer of NIPT has changed since then. At the time of our study, only Ontario provided state-funded NIPT for pregnancies with a positive prenatal screening result from multiple marker screening or satisfying another condition such as maternal age [9]. Since 2016, B.C., Yukon, and Quebec have also begun funding NIPT on a contingent model. Recommendations, such as those of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC), have also evolved. In 2013, the SOGC recommended that NIPT be “an option available to women at increased risk in lieu of amniocentesis”, while not deeming the technology ready to replace using biochemical serum markers yet [10]. The latest iteration of the recommendations issued in 2017 [11], notes that maternal plasma cell-free DNA should be offered to all women, with the understanding that it might not be provincially funded and it discusses its use to detect, among others, microdeletions and sex chromosome aneuploidies.

These developments mean that our results are still relevant. Some of the “future uses” we discuss (such as whole genome sequencing) are still not offered today and have thus remained “future”. Other results are still relevant, but while at the time they pointed to hypothetical concerns regarding the offer of NIPT, these have now become actual concerns. For example, NIPT is currently offered in some places for sex chromosomes abnormalities, which was a hypothetical scenario at the time of our studies.

We note that we use the term NIPT in order to stay consistent with the terminology as presented to study participants, even though terminology has since shifted and much of the literature currently uses NIPS (for Screening) or “cell-free DNA screening” (or cfDNA screening).

Materials and methods

Study design

Interviews

A qualitative description (QD) methodology was used to allow answering questions of relevance to practitioners and policy makers. Interviewees were asked to reflect on the potential future uses of NIPT including paternity testing, sex determination, fetal aneuploidies and monogenic diseases, FWGS and late-onset diseases. QD provides direct information about a topic and a comprehensive explanation of this topic as viewed and experienced by the study participants [12]. We used QD to explore the perspectives and values of HCPs regarding the potential future uses of NIPT. In turn, these results can be used to inform practitioners, as well as policy decision-makers, about challenges raised by the potential future uses of NIPT. The interview guide used to collect data is provided as a supplementary file to the manuscript (Additional file 1).

Survey

To examine Canadian health professionals’ attitudes towards NIPT, a survey ran during a 16-month period, from March 2015 to July 2016.

The questionnaire had 28 questions addressing the following themes: knowledge about NIPT, decision-making when offering NIPT, uses of NIPT, social impact of NIPT, and future uses of NIPT. Question formats included Likert scales, ‘true or false’ statements, multiple choice, and ranking. The questionnaire included an information sheet explaining the differences between maternal serum screening, amniocentesis and NIPT. The information sheet gave brief descriptions of the procedures, timing of tests, risk for pregnancy, accuracy, nature of test (screening vs diagnostic), potential results, and potential outcomes (Additional file 2).

Both studies were conceived in the context of a larger pan-Canadian project titled “PErsonalized Genomics for prenatal Aneuploidy Screening USing maternal blood” (PEGASUS). It is noteworthy that data collection for interviews was performed a year earlier than the survey. However, the fact that they shared similar themes that were initially developed based on the same literature review [13], allowed us to compare the results from both. Results from interviews thus informed the analysis and clarified the interpretation of survey results.

Sampling and recruitment

In total, 25 HCPs working in prenatal screening and diagnostic testing in Montreal were invited to participate in our interviews between October 2014 and February 2015. They were identified through collaborators who provided a list of HCPs practicing prenatal testing as well as through an online-search. H.H. conducted the semi-structured interviews with the 10 HCPs who accepted to take part in our study, in French, face-to-face at the respondents’ workplaces. We stopped recruitment after reaching data saturation.

Recruitment for the survey occurred primarily at 6 hospitals in five Canadian provinces (BC, Alberta, Ontario, Québec, and Newfoundland). HCPs were also recruited at conferences and via mailing lists of 41 Canadian professional societies.

Data analysis

We used thematic analysis to conduct our data analysis for interviews, facilitated through the software package NVivo 11. Data collection and analysis were done concurrently. Transcripts were read repeatedly (by H.H. and G.B.) and broken down into subcodes merged under higher-order code categories that were already established by using the deductive approach of analysis (predefined code categories). To ensure the consistency of coding, both researchers independently coded a subset of transcripts, which were then compared against each other to ensure inter-coder reliability, i.e. “a numerical measure of the agreement between different coders regarding how the same data should be coded” [14]. During this process both researchers met regularly, and discussed discrepancies until consensus was reached to refine the coding, thus improving precision. H.H. translated selected quotes into English.

Survey data was stored and analyzed using IBM SPSS 24. An exploratory inductive approach to the data was taken, with no hypotheses formulated a priori.

Results

Interviewees included: two registered nurses, four medical geneticists, three obstetricians/gynecologists and one genetic counselor (Table 1).

184 HCPs from 8 Canadian provinces and 1 territory completed the survey. 50% practiced primarily at a public hospital, 20.7% at a research hospital, 15.2% at a private practice, and 5.4% at a public health organization. 89.0% reported having experience in prenatal diagnosis for Down syndrome, and 81.1% reported offering NIPT (Table 2).

Paternity testing

Respondents to the survey were mixed in how favorable they were to using NIPT to test for paternity, with 39.0% not in favor of using NIPT for paternity testing, 19.2% in favor of using it for paternity testing, and the remainder (41.8%) in between (see limitations).

All interviewees agreed that NIPT should not be offered for paternity testing, unless there is a medical reason to do so. See Table 3 for selected quotes illustrating professionals’ views.

Sex determination

NIPT to determine the sex of the fetus for medical reasons was positively perceived by all interviewees because, according to the majority, “determining fetal sex for medical reasons is something that is already done in clinic with other technologies and it allows guiding the pregnancy management”. Non-medical sex determination, however, elicited negative reactions from all interviewees. They feared that it would lead to termination based on sex or what is euphemistically called “family balancing”.

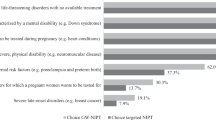

Specific uses of NIPT: expansion to other chromosomal disorders, inherited disorders, late-onset diseases, and fetal whole genome sequencing (FWGS)

Within our discussion with HCPs, we tackled more specific uses of NIPT, some of which are already offered in the clinic, including: chromosomal disorders such as fetal aneuploidies (trisomy 13, 18, 21) and inherited disorders (such as cystic fibrosis), while others are more speculative or performed in research settings, such as FWGS and fetal testing for late-onset diseases.

Expansion to other chromosomal disorders and inherited disorders

Of all potential expanded uses of NIPT, survey respondents were most in favor of this category, that was presented to them as “inherited disorders (Tay-Sachs, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, Gaucher disease)”. 63.4% of respondents were in favor, while 4.9% not in favor.

Survey respondents were asked how useful it is to perform NIPT in low-risk pregnancies “to look for other chromosomal anomalies, including microdeletions and microduplications, using chromosomal microarrays or comparative genomic hybridization”. 34.1% of respondents were not in favor of such use of NIPT, 8.9% were in favor, and 57.0% fell in between. Interestingly, HCPs who reported having experience in prenatal diagnosis for DS were significantly less interested in such expanded use of NIPT than those who reported having no such experience in prenatal diagnosis for DS (p = 0.019, 2-sided Pearson Chi-Square test).

In interviews, almost all HCPs supported the use of NIPT to test for fetal aneuploidies. When we probed for more specific chromosomal abnormalities beyond the common ones (trisomy 21, 13 and 18) such as 47,XXY (Klinefelter syndrome) and 45,X (Turner syndrome), we identified agreement among the interviewees who stated that there is no need to test for Klinefelter syndrome since there is no medical indication to terminate the pregnancy.

In the case of testing for Turner syndrome, HCPs thought it should be performed only following an ultrasound showing clinical signs indicating a severe form with medical complications, for which pregnancy termination could be considered.

Testing for monogenic diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF) is still not possible, in clinical or research settings. All interviewees considered the use of NIPT to diagnose CF to hold great potential and to possibly eventually replace more invasive procedures (amniocentesis and CVS) if it becomes clinically available. Nevertheless, they emphasized the fact that it should not be universally offered to all pregnant women and should be limited to specific cases, such as couples known to be carriers.

NIPT use for late-onset diseases

The survey had three sub-questions on the desirability of expanding NIPT use to test for genetic predispositions for disease: 1. “Predisposition to childhood-onset diseases (autism, leukemia)”; 2. “Predisposition to late-onset diseases (heart conditions, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer)”; and 3. “Predisposition to mental disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disease)”. The responses are shown in Table 2.

These results were not homogeneous across types of HCPs surveyed for late-onset and mental disorders, with clinical geneticists, genetic counselors, and general practitioners being significantly less in favor of testing for such predispositions than nurses, midwives or ob/gyn’s (p < 0.001 for both categories of conditions).

Using NIPT to detect late-onset diseases has spurred diverse opinions among interviewees. Those opinions were equally divided between those who were completely opposed to offering the test for late-onset diseases and those who were in favor of offering it in a controlled manner.

Reasons invoked for not offering the test included: possibility of having a treatment in the future for the detected condition, labeling of the future child (alluded to above), lack of immediate impact on the child’s development and health, and the fact that, in most cases, the results generated reflect a risk factor and not a certainty. Even in the event of a diagnosed late-onset condition they argued that “the future baby will have enough time to live and will lead a normal life”. (HP 1)

Interviewees who were in favor of offering it for late-onset diseases were very cautious about framing the conditions under which the test should be used. Some focused on the reliability of the test to diagnose late-onset diseases and to predict its occurrence, especially for severe diseases such as Huntington disease, for which couples may consider terminating the pregnancy. Further, they stressed the need for extensive pre-test genetic counseling and a follow up with a psychologist.

Others stated that the personal lived-experience of predisposition to late-onset diseases for each person should be taken into consideration because the risk for a certain late onset-disease (such as breast cancer) might be perceived differently and the way each individual experiences it is distinct and depends on their personal history. Further, it is difficult for a HCP to judge whether a risk is severe enough to justify a prenatal test:

That is always the debate. I work a lot in hereditary cancer, so women with BRCA who are at risk of cancer. We often see, let’s say, all ways of thinking. There are people, who even if they are carriers, do not change their reproductive decisions, knowing that screening is a possibility. There are other people, and it is often those who have catastrophic family histories, young women who lost their mother when they were babies, with a very, very strong history, could experience that risk very intensely. So I find myself not well-placed to judge, to say that no, it’s not severe enough to justify a prenatal test, because they all have different life experiences, some people really have catastrophic histories, and we can understand that this is something they absolutely want to avoid transmitting… (HP 9)

NIPT use for FWGS

In a relatively near future, the ongoing technological development of NIPT may provide couples with the opportunity to access information about the sequence of the whole genome of their fetus, thus revealing extensive information of either health-related significance, such as increased genetic predisposition to develop certain diseases, or non-health related significance, such as the fetus’ eye color and other non-medical traits.

In total, 92.8% of survey respondents were not in favor of using NIPT to test for “physical and behavioral attributes (eye color, intelligence, sexual orientation)”.

We discussed with interviewees whether they would be in favor of offering NIPT in order to know the entire genomic sequence of their patient’s fetus. Although most interviewees foresaw prenatal FWGS as an unavoidable reality in the future, 8 of 10 voiced a resounding “no” to its use, raising concerns on five different levels: (1) current lack of scientific knowledge related to genetic findings, (2) lack of treatment, (3) difficulty in achieving consent and counseling, and (4) the future child’s autonomy, and (5) the trivialization of pregnancy termination.

Many interviewees were concerned about the vast amount of complex genetic information generated through FWGS, as well as the current lack of knowledge and difficulty in interpreting and managing genetic findings, such as variants of unknown significance. To illustrate this situation, some interviewees cited their experience with comparative genomic hybridization- a technique detecting chromosomal copy number changes to provide global overview of either gains or losses of whole chromosomes or subchromosomal regions [15]—as an example where they were unable to interpret genetic results.

Further, they added that prospective parents would be overwhelmed with the quantity and complexity of the information, which might consequently be troubling for them and increase their stress. Within HCPs’ discussions about the complexity of the information, they voiced concerns related to both the difficulty in obtaining consent and in providing counseling. Many recognized that the consent needs to be “rock solid” since it is hard to know what findings will be generated through FWGS.

Lack of cure, treatment, and prevention, particularly in some specific cases such as late-onset diseases, were other commonly cited reasons for rejecting the use of NIPT for FWGS.

I would not be in favor because it is like going fishing and finding things that are not related to what is important to the women or couple. And then the predictive powers that we have right now by sequencing the whole genome are inconclusive. So, some things we are going to find for which we have no treatment, we do not expect the fetus to be affected. There would be like late onset. And even in these late onset diseases, there would be no screening or curative treatment. (HP 10)

Many HCPs felt unease about the expanded use of FWGS, because they thought it will open the door to “frivolous applications”, such as selecting sex, eye color, or risk of developing a certain condition, which might in turn lead to the trivialization of pregnancy termination.

Two interviewees voiced concerns related to the impact of FWGS on the child’s right to decide for themselves whether to undergo genetic testing, while simultaneously labeling them as a carrier of a certain condition, thereby possibly affecting their mental health and making employment or insurance more difficult to obtain later in life.

Even the two interviewees who agreed about the use of NIPT for FWGS said that it should be used as a last resort after more invasive or known procedures are performed, such as amniocentesis for CGH, and under very specific medical indications. Moreover, it should not be offered to the population “at large”.

Discussion

Since the introduction of prenatal tests in 1970, the scope of detected genetic conditions was limited to situations where the probability of being affected was high, thus ‘justifying’ invasive testing. However, the emergence of NIPT is significantly changing this landscape by paving the way for testing and/or diagnosing a much wider range of medical and non-medical conditions in the absence of perceived specific risks. In light of this, our study aimed to explore the views of HCPs in relation to current and potential future uses of NIPT. Our findings show that there is agreement among HCPs on expanding NIPT use for medical conditions including fetal aneuploidies and monogenic diseases, but not for non-medical conditions (sex determination for non-medical reasons and paternity testing), and risk predisposition information (late onset diseases and FWGS).

Our discussion reflects concerns that might have transitioned from being purely hypothetical at the time of data collection (e.g. NIPT was not offered for Klinefelter syndrome) to being currently real scenarios (NIPT is being offered for Klinefelter in some provinces), while others are still futuristic and considered controversial (NIPT use for FWGS). This is due to the technological development of NIPT that led to growing reliability for certain conditions. We will discuss ethical concerns raised by HCPs regarding the expansion of NIPT use for non-medical conditions and risk predisposition information and that we grouped under three umbrellas: those related to the society at large, to the parents, and to the prospective child. We do acknowledge that this organization is somewhat overlapping in nature, and we adopt it here for heuristic reasons.

Concerns related to the society

HCPs voiced concerns at a societal level, including the trivialisation of pregnancy termination (i.e. abortion for trivial or unimportant reasons) and increased eugenic trends, if NIPT is used for non-medical conditions such as sex determination for non-medical reasons. HCPs’ concerns seem to join those raised by the public in previous studies. For instance, in their study of public viewpoints, Farrimond and Kelly report that “…fears about trivialisation are linked to the rejection of picking and choosing and a valuation of natural diversity such as disability. As such, trivialisation fears are not fears about having greater information per se, but are rather the fear of the trivialisation of abortion”[16] (p740, 2011). Trivialisation of pregnancy termination might lead to loss of diversity in society, which in turn, might exacerbate discriminatory attitudes towards those individuals who present traits that are different from what is accepted in a eugenic society, a society looking for “perfect babies” [17]. These concerns are not novel. However, they are likely to be exacerbated with NIPT used to test for a wider range of conditions as the technology evolves.

To address these concerns, in light of our findings, we think there is a need: (1) to perform evidence-based studies in relation to what conditions should be tested for (and under what circumstances); for instance, severe vs. minor ones, and (2) promote a public discussion involving points of views from diverse stakeholders, including disability groups and policy makers.

Concerns related to the parents

Extending the scope of NIPT use to FWGS and late-onset diseases raises the challenge of processing an unprecedented amount of complex genomic data, which according to our findings is likely to result in concerns on two levels. First, a psychological and emotional concern rooted in the anxiety and stress faced by parents when coping with the uncertainty of how to handle and act upon receiving overwhelming and sometimes ambiguous information [18, 19].

Second, there is the practical concern of the difficulty of achieving both effective counseling and informed consent, explained by the lack of a full comprehensive understanding of the potentially generated results, by the complexity and vast amounts of genetic information, and by the shortage of appropriately trained HCPs [20]. These concerns have been reported in recent studies where surveyed Ob/Gyns in the United States noted that they are uncomfortable counseling patients about expanded carrier testing [21] and do not have enough time to counsel patients about NIPT [22]. Further, while a non-directive approach is the professional advocated norm when it comes to counseling and to offering balanced and neutral information regarding testing and pregnancy management to pregnant people and their partners, a finding worthy of highlighting is that some HCPs might still “orient” or “guide” pregnant people to terminate a pregnancy in certain medical conditions, as noted in one reported quotation (Table 3). This situation, although clinically common [23], interferes with pregnant people and partners’ decision-making regarding pregnancy management, thereby undermining their informed choice.

Concerns related to the prospective child

The infringement on the privacy of the future child is often discussed in the literature in terms of the breach of the child’s ‘right to an open future’ [24, 25] and is cited as one among diverse consequences of expanding NIPT to include late onset diseases and FWGS. Our findings indicate HCPs’ worry that this violation might cause psychological harm to the future child and impact her future life by labeling her as a disease carrier, which consequently might hinder access to employment and insurance coverage. These concerns resonate with the findings and discussions raised in the literature around noninvasive prenatal whole genome sequencing [26, 27].

While these concerns are not new, they pose challenges to how the use of NIPT for FWGS should be handled and regulated in practice. For instance, should parents be allowed to access the fetal genome during pregnancy even if it is only for information [28]? Should they only access the medical information that will allow them to take a specific course of action based on their medical history (for instance, risk of the child to develop Huntington disease)? How should these decisions be made and by whom? While these questions are worth analyzing, they are beyond the scope of this paper. However, these findings suggest that there is a need to educate and counsel parents, pregnant persons, and couples and to equip HCPs with the necessary tools (such as guidelines) so that they are able to cope with the challenges raised by NIPT and its possible expanded use.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the triangulation, combining both quantitative and qualitative methods, and thus allowing a deeper understanding of the quantitative results through the analysis of qualitative ones. Nevertheless, it presents limitations in both methods.

For the qualitative component, the recruitment took place in two medical institutions located in the Montreal area where NIPT was not yet widely offered, restraining therefore the diversity of HCPs’ views from other medical establishments and locations as well as their medical specialties, that were limited to four: Ob/gyn, medical geneticists, genetic counselors, and nurses. Including more professional groups from different geographical locations and medical specialties (such as family physicians) in future research will enrich the diversity of the data collected. Further, despite achieving saturation after 10 semi-structured interviews based on pre-defined themes, we acknowledge that other themes could have been developed if additional interviews were conducted. However, considering our deductive approach, this does not invalidate our results. Finally, the categories ‘medical’ and “non-medical” conditions were not interrogated with interviewees, thereby relegating all aneuploidies, e.g., to the ‘medical’ category, which is not an uncontroversial classification.

The survey portion of the study has its limitations as well. First of all, while respondents were selected from the population of HCPs treating pregnant persons on a daily basis, some respondents reported more regular experience with pregnancies considered at high risk than others. Selection bias is possible, since it is possible that respondents with a particular set of attitudes towards NIPT were more likely to self-select to respond to the survey. Not having asked about sex selection in the questionnaire is a limitation for the present study, as we cannot triangulate the qualitative results.

Conclusion and future research

This study reflects HCPs’ perceptions regarding the potential future uses of NIPT, including paternity testing, sex determination, fetal aneuploidies, heritable monogenic diseases, late-onset diseases, and FWGS. It shows that while HCPs approve of the expansion of NIPT use for certain medical conditions, they raise diverse concerns, such as eugenics and the privacy of the future child. These concerns should be taken into account when making decisions on how to best incorporate the expanded uses of NIPT into clinical practice. Professional societies play a crucial role in educating both HCPs and parents on the potential future uses of NIPT.

As the expansion of NIPT uses seems to be imminent, further research is needed to explore what conditions should be offered to couples or parents and based on which criteria. It will be important as a society to engage in these discussions to allow a most ethically responsible clinical implementation of NIPT.

Data availability

The qualitative interview data analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they might potentially include identifying information that could compromise research participant privacy and consent. Sections of anonymized data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The interview guide used to collect data is provided as a supplementary file (Additional file 1) to the manuscript.

The survey questionnaire is provided as an additional file to the manuscript (Additional file 2).

References

Quezada MS, Gil MM, Francisco C, Oròsz G, Nicolaides KH. Screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 by cell-free DNA analysis of maternal blood at 10-11 weeks’ gestation and the combined test at 11-13 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45:36–41.

Taylor-Phillips S, Freeman K, Geppert J, Agbebiyi A, Uthman OA, Madan J, et al. Accuracy of non-invasive prenatal testing using cell-free DNA for detection of Down, Edwards and Patau syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010002.

Guseh SH. Noninvasive prenatal testing: from aneuploidy to single genes. Hum Genet. 2020;139:1141–8.

Birko S, Lemoine M-E, Nguyen M, Ravitsky V. Moving towards routine non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): challenges related to women’s autonomy. OBM. Genetics 2018;2:1–14.

Haidar H, Le Clerc-Blain J, Vanstone M, Laberge A-M, Bibeau G, Ghulmiyyah L, et al. A qualitative study of women and partners from Lebanon and Quebec regarding an expanded scope of noninvasive prenatal testing. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:54.

Bowman-Smart H, Savulescu J, Mand C, Gyngell C, Pertile MD, Lewis S, et al. ‘Is it better not to know certain things?’: views of women who have undergone non-invasive prenatal testing on its possible future applications. J Med Ethics. 2019;45:231–8.

Benachi A, Caffrey J, Calda P, Carreras E, Jani JC, Kilby MD, et al. Understanding attitudes and behaviors towards cell-free DNA-based noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT): A survey of European health-care providers. Eur J Med Genet. 2019;63:1–8.

Kater-Kuipers A, Bunnik EM, de Beaufort ID, Galjaard RJH. Limits to the scope of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): an analysis of the international ethical framework for prenatal screening and an interview study with Dutch professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:409.

Vanstone M, Yacoub K, Giacomini M, Hulan D, McDonald S. Women’s experiences of publicly funded non-invasive prenatal testing in Ontario, Canada: considerations for health technology policy-making. Qualitative Health Res. 2015;25:1069–84.

Langlois S, Brock JA, Wilson RD, Audibert F, Brock JA, Carroll J, et al. Current status in non-invasive prenatal detection of Down syndrome, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13 using cell-free DNA in maternal plasma. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35:177–83.

Audibert F, De Bie I, Johnson JA, Okun N, Wilson RD, Armour C, et al. No. 348-Joint SOGC-CCMG guideline: update on prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, fetal anomalies, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:805–17.

Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33:77–84.

Haidar H, Dupras C, Ravitsky V. Non-invasive prenatal testing: review of ethical, legal and social implications. BioéthiqueOnlne. 2016;5:1–14.

O’Connor C, Joffe H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qualitative Methods. 2020;19:1609406919899220.

Weiss MM, Hermsen MA, Meijer GA, van Grieken NC, Baak JP, Kuipers EJ, et al. Comparative genomic hybridisation. Mol Pathol. 1999;52:243–51.

Farrimond HR, Kelly SE. Public viewpoints on new non-invasive prenatal genetic tests. Public Understanding Sci. 2011;6:730–44.

Ravitsky V, Birko S, Le Clerc-Blain J, Haidar H, Affdal AO, Lemoine M, et al. Noninvasive prenatal testing: views of canadian pregnant women and their partners regarding pressure and societal concerns. AJOB Empirical Bioethics. 2020;1:53–62.

Shakespeare T. A Brave New World of Bespoke Babies? Am J Bioeth. 2017;17:19–20.

Donley G, Hull SC, Berkman BE. Prenatal whole genome sequencing: just because we can, should we? The. Hastings Cent Rep. 2012;42:28–40.

Ravitsky V, Roy MC, Haidar H, Henneman L, Marshall J, Newson AJ, et al. The emergence and global spread of noninvasive prenatal testing. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2021;22:309–38.

Benn P, Chapman AR, Erickson K, Defrancesco MS, Wilkins-Haug L, Egan JF, et al. Obstetricians’ and gynecologists’ practice and opinions of expanded carrier testing and non-invasive prenatal testing. Prenatal Diagn. 2013;2:145–52.

Farrell RM, Agatisa PK, Mercer MB, Mitchum A, Coleridge M. The use of noninvasive prenatal testing in obstetric care: educational resources, practice patterns, and barriers reported by a national sample of clinicians. Prenat Diagn. 2016;6:499–506.

Ravitsky V. The shifting landscape of prenatal testing: between reproductive autonomy and public health. Hastings Cent Rep.2017;47 Suppl 3:S34–40.

de Jong A, de Wert GM. Prenatal screening: an ethical agenda for the near future. Bioethics. 2015;29:46–55.

Chen SC, Wasserman DT. A framework for unrestricted prenatal whole-genome sequencing: respecting and enhancing the autonomy of prospective parents. Am J Bioeth. 2017;17:3–18.

Horn R, Parker M. Health professionals’ and researchers’ perspectives on prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing: ‘We can’t shut the door now, the genie’s out, we need to refine it’. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204158.

Haidar H, Iskander R. Non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal whole genome sequencing: an interpretive critical review of the ethical, legal, social, and policy implications. Can J Bioethics / Revue canadienne de bioéthique. 2022;5:1–15.

Deans Z, Clarke AJ, Newson AJ. For your interest? The ethical acceptability of using non-invasive prenatal testing to test ‘purely for information’. Bioethics. 2015;29:19–25.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants in this study and to those who helped in recruiting them. We also thank the American University of Beirut Medical Center and the Center hospitalier universitaire Sainte-Justine.

Funding

This study was completed under the PEGASUS (PErsonalized Genomics for prenatal Aneuploidy Screening USing maternal blood) grant, funded by Genome Canada, Genome Quebec, and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR). None of the funding bodies had any input regarding the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; nor in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HH and VR designed the qualitative study. HH collected the interview data. HH and GB analyzed the data, with input from JLCB, VR, AML. The survey was conceived by VR and AML, designed by VR, AML, JLCB, HH. Survey Data was interpreted by SB, VR, AML. HH and SB drafted the article. All authors critically reviewed the article and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Approval for this study was obtained from the research ethics committee at the Center hospitalier universitaire Sainte-Justine (CHUSJ) (#3976) in Montreal, Quebec, Canada in September 2014 and from the institutional review board (IRB) at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC), Beirut, Lebanon, in June 2015. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to data collection. Ethical approval for the surveys was obtained from the CHU Sainte-Justine associated with the University of Montreal (#3781) as well as from the CRCHU de Québec (#B14-10-2146), the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, BC Children’s Hospital, the University of Calgary, and the Newfoundland and Labrador Health Research Ethics Authority.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haidar, H., Birko, S., Laberge, AM. et al. Views of Canadian healthcare professionals on the future uses of non-invasive prenatal testing: a mixed method study. Eur J Hum Genet 30, 1269–1275 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01151-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01151-5

This article is cited by

-

Genome sequencing—do you know what you are getting into?

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)