Abstract

Children with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) may have a high burden of somatic disease and cognitive impairments, which can lead to poor academic performance. We evaluated school grades from exams ending mandatory schooling (usually around age 15 or 16 years) of children with NF1 in a population-based registry study using a within-school matched design. The study included 285 children with NF1 and 12,000 NF1-free peers who graduated from the same school and year during 2002–2015. We estimated overall and gender-specific grades by subject and compared the grades of children with NF1 with those of NF1-free peers in linear regression models. We also examined the effect of social and socioeconomic factors (immigration status and parental education, income and civil status) on grades and age at finalizing ninth grade. School grades varied considerably by socioeconomic stratum for all children; however, children with NF1 had lower grades by an average of 11–12% points in all subjects. In the adjusted models, children with NF1 had significantly lower grades than their NF1-free peers, with largest negative differences in grades observed for girls with NF1. Finally, children with NF1 were 0.2 (CI 0.1–0.2) years older than their peers on graduating from ninth grade, but only maternal educational modified the age at graduating. In conclusion, students with NF1 perform more poorly than their peers in all major school subjects. Gender had a strong effect on the association between NF1 and school grades; however, socioeconomic factors had a similar effect on grades for children with NF1 and their peers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) is a common single gene disorder with an incidence of ~1/2000 live births [1]. The disorder is inherited from a parent in approximately 50% of diagnosed individuals, while de novo pathogenic NF1 variants result in NF1 in the remaining individuals [2]. The diagnostic criteria include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, axillary and inguinal freckling, optic glioma, iris Lisch nodules, distinctive osseous lesion and identification of an NF1 pathogenic variant; the diagnosis is met if one criteria is present in individuals with a parent with NF1 or at least two of the criteria are present when no parent is diagnosed with NF1 [3].

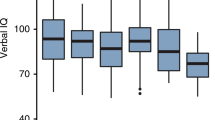

NF1 is a complex disorder, associated with a variety of clinical manifestations and complications, which reduce life expectancy [4, 5]. Although NF1 appears to be completely penetrant by age 20 years, the features vary widely, even among family members with the same pathogenic variant [6], and the symptoms that will develop in an affected individual cannot be predicted [7]. Aside from high hospitalization rates and accelerated mortality [8], persons with NF1 also experience an increased risk for psychiatric disorders and emotional burden [9, 10], loneliness [11], impaired quality of life [9] and cognitive impairments including lowered intelligence quotient (IQ) [12], impaired memory [13], symptoms of attention deficits [14] and impaired executive functioning [15].

To date, education of persons with NF1 has mainly been analyzed by addressing academic difficulties and specific disorders that may challenge children with NF1 in school such as visual–spatial deficits, dyslexia and dyscalculia, writing difficulties, attention deficits and executive dysfunction [16,17,18,19,20,21]. Both a Danish and Finnish population-based cohort study found overall lower academic level in adults with NF1 [22, 23], and a delayed progression in reaching academic milestones was also reported in the Danish study [22]. Although poor school performance can have long-term consequences for subsequent occupational and social life, the actual academic performance of schoolchildren with NF1 is currently unknown. Therefore, we used a population-based approach with the comprehensive nationwide Danish registries to investigate the ninth grade school grades of children with NF1 who attended public schools during the period 2002–2015. As social and parental socioeconomic factors are likely to influence academic performance and the effect might be different for children with NF1 than for their healthy peers, we also examined whether these factors modified the association between NF1 and school performance. In Denmark, ninth grade marks an educational milestone usually around age 15 or 16 years, ending mandatory schooling and opening the door for further educational or career paths.

Materials and methods

Study population and comparison cohort

Our source population included all Danish students registered in the Education Registry (N = 852,684) who finished ninth grade between 2002 and 2015. Within this population, we identified 285 children with NF1 diagnosed before the age of 15 years by linking the unique personal identification number of each child to our large cohort of all known patients with NF1 in Denmark (see detailed description of the cohort here [8]). Briefly, the national NF1 cohort comprises 2576 individuals who have been discharged from a hospital in Denmark with a diagnosis of NF according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) version 8 743.49 or ICD-10 Q85.0 during the period 1977–2013 or followed in one of two centers for rare diseases in Denmark. After exclusion of those with symptoms of NF2 (N = 59), the cohort consisted of 2517 individuals [8].

Within the source population, NF1-free peers who were in the same school as the 285 children with NF1 were selected for a comparison cohort of 12,000, thus obtaining a matched study population. All children were linked to the Danish Civil Registration System, which was established in 1968, to obtain information on migration and vital status.

Education registry

In Denmark, school grades of all students in public schools have been systematically registered annually in the Education Registry since the school year 2001–2002 [24]. We selected ninth class grades as the outcome measure of school performance and calculated average mean rank grades [25] for each student in each school year by including all available school grades. We evaluated general proficiency based on all grades obtained by nationwide standardized test with external evaluation and grades based on the performance over the academic year given by the subject teacher. We also distinguished the grades according to whether they were oral or written grades. Finally, we included grades for the following subjects: Danish, English and mathematics. Rank-based grades by default have a mean of 50 (50th percentile). As mean rank grades were calculated for the entire student population, 50 is the median grade for the entire population. This means that if the grade of a child was calculated to 80 then the child’s grade corresponded to the 80th percentile among children attending the same school that given year. The method used has been described in detail by Andersen et al. [25, 26]. Use of a matched design minimized unmeasured confounding, as all comparisons were made in the same school with the same teachers.

Information on social and socioeconomic factors

The parents of the students were identified in the Danish Civil Registration System and linked to their children though the Danish Fertility Database. For all students, we included four markers of social and socioeconomic status: parents’ educational level, income and civil status (married/unmarried) and child’s immigration status. Information on parental educational level was obtained from the Attainment Register, which was established in 1970 [24] and was classified into three groups according to the corresponding International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-2011) codes: short (ISCED codes 1–2, ≤9 years), medium (ISCED 3–4, 10–12 years) and long (ISCED 5–8, >12 years) [27]. Parental income was obtained from the Income Statistics Register, established in 1970 [28], and grouped into quintiles, the first quintile representing the lowest income group. Information on civil status was retrieved from the Danish Civil Registration system as a binary variable, “married” (married couples and registered partnerships) and “unmarried” (individuals who were divorced, widower/ed or never married). Information on the child’s immigrant status and country of origin was also retrieved from the Danish Civil Registration System as a binary variable, divided into immigrant or children of immigrants (children whose parents were neither born in Denmark nor had the Danish citizenship) and Danish origin [29].

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the study population were reported as proportions stratified by NF1 status. We tested differences between children with NF1 and their NF1-free peers by means of chi-squared tests. We used linear regression models to investigate marginal associations and tested differences in mean rank grades between children with NF1 and NF1-free peers within each stratum of the variable. We examined whether social and socioeconomic factors (parental education, income and civil status and immigration status of the child) modified the association between NF1 and the mean rank grades after adjustment for gender, birth year, and school year in ninth grade. All variables were modelled as categorical variables, as defined previously. The possible effect modification by each social and socioeconomic factor was tested in separate models, and the significance of model terms was evaluated by means of likelihood-ratio tests with a 5% significance level. Similarly, we examined whether the social and socioeconomic factor modified the association between NF1 and age at graduation from ninth grade, adjusted for gender, birth year, and school year in ninth grade.

Finally, we analyzed the effect of NF1 on ninth-year grades in a fully adjusted model for school year in ninth grade, birth year, parental civil status, parental education, parental income and child’s immigration status, with the reference being the NF1-free peers. The analysis was conducted for the overall mean grade and for subject-specific grades, stratified by gender. We used the statistical software R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) for data analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

The NF1 cohort consisted of 285 students (50% female) who were compared with 12,000 NF1-free peers (48% female) (Table 1). The gender distribution, school year in ninth grade, parental income, parental education, parental civil status and child’s immigration status did not differ significantly between children with NF1 and their NF1-free peers. Paternal income and maternal education were lower at borderline significance in the NF1 group (Table 1); however, students with NF1 were significantly older than their peers when they finished ninth grade (P = 0.01).

Table 2 shows the estimated mean rank grade for each school subject stratified by social and parental socioeconomic factors. In the univariate analyses, significant differences were found in mean rank grades between children with NF1 and their peers for most socioeconomic factors, including parental income, parental education, parental civil status and child’s immigration status (P < 0.05) (Table 1). The average deficit in rank grades was 11–12% point (Table 2).

Figures 1 and 2 show the effects of social and socioeconomic factors on the association between school grades and age at finishing ninth grade. We found no significant effect modification of social or socioeconomic factors on the association between NF1 and mean rank grades, after adjustment for gender, birth year and school year in ninth grade (Fig. 1). In other words, children with NF1 were affected by social and socioeconomic factors to the same extent as their NF1-free peers. Maternal education, however, modified the association between NF1 and age at finishing ninth grade (P = 0.002). Thus, students with NF1 whose mothers had short or medium education were older than their peers when they finished ninth grade, while NF1 students of mothers with long education finished at a similar age as their peers. Maternal income was of borderline significance (P = 0.09), probably due to the significant correlation with maternal education (Fig. 2).

We also estimated the effect of NF1 on overall oral and written grades, grades in Danish, English and mathematics and age at graduation from ninth grade, stratified by gender. Students with NF1 had significantly lower rank grades than their peers after adjustment for school year in ninth grade, birth year, parental civil status, parental education, parental income and child’s immigration status (Fig. 3). In all subjects, girls with NF1 had lower mean rank grades than their NF1-free peers (girls with NF1: −11.7 to −14.5; boys with NF1: −6.9 to −8.0), corresponding to the 35–38 percentile for girls with NF1 and 42–43 percentile for boys with NF1 (Fig. 3). The effect of NF1 on age at graduation showed a coefficient of 0.2 years (95% CI 0.1–0.2) in comparison with NF1-free peers (data not shown). Thus, students with NF1 were older than their NF1-free peers when they finished ninth grade.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first nationwide population-based study to explore the academic performance of children with NF1 and to assess if social and socioeconomic factors modified their school performance. Our primary findings showed that children with NF1 had an overall significant impairment in school performance, which was more pronounced in girls with NF1 than in boys with NF1 when compared with NF1-free girls and boys, respectively. This result was consistent for all written and oral course subjects and categories.

The effect of NF1 on overall school grades in this study was even larger than the effect reported in a similar Danish study of school grades in students after childhood cancer. Here, the largest effect was seen in survivors of central nervous system tumors with a 6 percentile deficit [25], which is similar to our observation in boys with NF1 (7 percentile deficit), but less than in girls with NF1 (14 percentile deficit). With the median being the 50 percentile, girls and boys with NF1 belong to the 43 and 36 percentile, and have a similar or lower mean rank score than children previously diagnosed with a central nervous system tumor. Thus, we found that NF1-free boys had a lower overall mean rank score than NF1-free girls (Table 2), which is in line with results from previous international surveys where boys tend to underachieve in e.g. reading at primary- and secondary-school levels [30]. The results from the linear regression showed, however, a larger effect of NF1 on school grades for girls than boys with NF1, which might be explained by the higher school grades observed in NF1-free girls than in NF1-free boys. We have shown that adults with NF1 reach significantly lower educational levels than NF1-free matched population comparisons [22]. As low early school achievement has been found to be the strongest predictor of low and short educational achievement in adulthood [31], both girls and boys with NF1 should be given additional support to optimize their school performance.

As NF1 is a Mendelian disease, where about half of all individuals inherit NF1 from a parent, we examined whether the socioeconomic status of the families had a different effect on school grades of children with and without NF1. Although the mean rank grades varied considerably among children with NF1 and their healthy peers in all social and socioeconomic strata, the effects of social and socioeconomic factors on school grades were similar for children with and witout NF1. However, the children with NF1 were older than their peers when they finished ninth grade. While long maternal education was associated with a similar age at graduation, short maternal education was associated with an older graduation age in children with NF1. In a Finnish population-based register study of 1,000,000 individuals in the general population, the mothers’ education affected school peformance in the early school years [31], whereas the fathers’ educational level seem to have more influence in later school years and early adulthood [32]. As children with NF1 of mothers with a short education level appear to be at higher risk for repeating a grade or starting later in school, additional attention should be paid to the school performance of these children.

Of 17 Belgian schoolchildren with NF1 (mean age, 9.2 years; range, 7–11 years) fewer than half had learning problems after a lower IQ was accounted for in evaluating academic performance. Academic achievement may relate to complex executive functions [33], including the creation and implementation of a plan, self-monitoring and cognitive flexibility [34], which are needed skills of school success [35]. With executive functioning, excellent reading, writing and mathematical skills are essential for achieving high grades. In a study of 86 children with NF1, 75% performed significantly less well than their peers in at least one of the domains of spelling, mathematics, technical reading or comprehensive reading, indicating learning disabilities [36]. Thus, some children with NF1 seem to lack essential skills needed to perform those academic tasks in school. Further, children with NF1 seem to repeat early grades more frequently (53%) than NF1-free children (25%) [37], which is in line with our finding of a higher age at finishing ninth grade among children with NF1. Their lower academic performance is probably also due to neurocognitive deficits, including a reduced IQ [12], for which children with NF1 are at increased risk [38], as well to NF1-related treatment and hospitalization [8] resulting in absence from school [16].

Both attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder are more prevalent in children with NF1 than in the general population [9, 39]. ADHD is, however, more often underdiagnosed in girls than in boys [40], and they consequently receive less support, which could limit their performance and may explain in part our finding of a larger effect of NF1 on school grades of girls with NF1 than boys with NF1. As previously shown [11], loneliness has been correlated with illness burden in Danish teenagers and young adults with NF1, which could be more striking in teenage females, aggravating psychosocial problems that could impair the school performance, including being more introverted or less self-confident. As school grades are of great importance for entering and accessing academic or career paths, low school performance may limit occupational options. Thus, schoolchildren with NF1 require early support to enhance their school performance and complete school at the same age as their peers.

Strength and limitations

According to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate school grades using a comparison-cohort design. A strength of the study is the availability of nationwide population-based registry data on school performance and detailed social and socioeconomic indicators, which enabled us to conduct the largest study of the academic performance in children with NF1 to date. Furthermore, the availability of objective data on the heterogeneous national population of students limited the risks for information bias on school grades as well as selection of a biased study population. By using a design of matching children with NF1 with peers from same school, we were able to avoid unmeasured confounding due to differences in school environment.

A major limitation of the study is the absence of grades of children attending private schools, in which up to 18% of Danish children in the compulsory form levels attend [41]. As private schools in Denmark have fewer children with special needs than public schools, we would expect that the differences in academic performance would be even greater if grades from private schools were included. Furthermore, school grades have been registered only since 2001, resulting in a relatively small sample for the present study and consequently in low statistical power. Lastly, we had no information on additional support in schools to children with special needs, which may have had a positive influence on their grades.

Our findings suggest continuing research with a multi-methodological study design of specific support approaches for students with NF1 considering gender differences to improve their school grades and increase their academic performance. It would be important to evaluate whether school grades are correlated with attained education in adult life by linking data from this study with data from our study on the highest attained educational levels in adults with NF1 and to include information on occupational status and income. The effects of both somatic and psychiatric diagnoses on these important milestones in life should be defined in order to identify children with NF1 who require additional support in school.

In this nationwide cohort study, we found that children with NF1 obtained lower school grades than their NF1-free peers- Although the effect of NF1 was larger on school grades in girls with NF1 than boys with NF1, we observed the lowest mean rank grades for boys with NF1. Children with NF1 were older when they finished ninth grade, and maternal educational level had a significant effect on the age at completing ninth grade among children with NF1. Children with NF1 should receive additional school support, as low academic performance has negative consequences for future socioeconomic status, career choices and income.

Data availability

All data are stored on a secure platform at Statistics Denmark (www.dst.dk/en) and can only be accessed remotely. The study group welcomes collaboration with other researchers. Study protocols can be planned in collaboration with us, and the data can be analysed accordingly at the server of Statistics Denmark. Access to data can only be made available for researchers who fulfil Danish legal requirements for access to personal sensitive data. Please contact Professor Jeanette Falck Winther (jeanette@cancer.dk) or senior researcher Line Kenborg (kenborg@cancer.dk) for further information.

References

Uusitalo E, Leppavirta J, Koffert A, Suominen S, Vahtera J, Vahlberg T, et al. Incidence and mortality of neurofibromatosis: a total population study in Finland. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:904–6.

Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:834–43.

Legius E, Messian L, Wolkenstein P, Pancza P, Avery RA, Berman Y, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1 and Legius syndrome: an international consensus recommendation. Genet Med. 2021;23:1506–13.

Evans DGR, O’Hara C, Wilding A, Ingham SL, Howard E, Dawson J, et al. Mortality in neurofibromatosis 1 in north Wwest England: an assessment of actuarial survival in a region of the UK since 1989. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:1187–91.

Duong TA, Sbidian E, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Vialette C, Ferkal S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Mortality associated with neurofibromatosis 1: a cohort study of 1895 patients in 1980–2006 in France. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:18.

Boyd K, Korf B, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.051.

Friedman JM, Birch PH. Type 1 neurofibromatosis: a descriptive analysis of the disorder in 1,728 Patients. Am J Med Genet. 1997;143:138–43.

Kenborg L, Duun-Henriksen AK, Dalton SO, Bidstrup PE, Doser K, Rugbjerg K, et al. Multisystem burden of neurofibromatosis 1 in Denmark: registry- and population-based rates of hospitalizations over the life span. Genet Med. 2020;22:1069–78.

Kenborg L, Andersen EW, Duun-Henriksen AK, Jepsen JRM, Doser K, Dalton SO, et al. Psychiatric disorders in individuals with neurofibromatosis in Denmark: a nationwide register-based cohort study. Am J Med Genet A. 2021;185:3706–16.

Doser K, Andersen EW, Kenborg L, Dalton SO, Jepsen JRM, Krøyer A, et al. Clinical characteristics and quality of life, depression and anxiety in adults with neurofibromatosis type 1: a nationwide study. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2020;182:1704–15.

Ejerskov C, Lasgaard M, Østergaard JR. Teenagers and young adults with neurofibromatosis type 1 are more likely to experience loneliness than siblings without the illness. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:604–9.

Ferner RE, Hughes RaC, Weinman J. Intellectual impairment in neurofibromatosis 1. J Neurol Sci. 1996;138:125–33.

Zöller ME, Rembeck B, Bäckman L. Neuropsychological deficits in adults with neurofibromatosis type 1. Acta Neurol Scand. 1997;95:225–32.

Pride NA, Payne JM, North KN. The impact of ADHD on the cognitive and academic functioning of children with NF1. Dev Neuropsychol. 2012;37:590–600.

Plasschaert E, Eylen LV, Descheemaeker M, Noens I, Legius E, Steyaert J. Executive functioning deficits in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: the influence of intellectual and social functioning. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2015;171B:348–62.

Coudé FX, Mignot C, Lyonnet S, Munnich A. Academic impairment is the most frequent complication of neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF1) in children. Behav Genet. 2006;36:660–4.

Orraca-Castillo M, Estévez-Pérez N, Reigosa-Crespo V. Neurocognitive profiles of learning disabled children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:386.

Cutting LE, Levine TM. Cognitive profile of children with neurofibromatosis and reading disabilities. Child Neuropsychol. 2010;16:417–32.

Gilboa Y, Rosenblum S, Fattal-Valevski A, Toledano-Alhadef H, Josman N. Is there a relationship between executive functions and academic success in children with neurofibromatosis type 1? Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2014;24:918–35.

Watt SE, Shores A, North KN. An examination of lexical and sublexical reading skills in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Child Neuropsychol. 2008;14:401–18.

Gilboa Y, Josman N, Fattal-Valevski A, Toledano-Alhadef H, Rosenblum S. Underlying mechanisms of writing difficulties among children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Res Dev Disabil. 2014;35:1310–6.

Doser K, Kenborg L, Andersen EW, Bidstrup PE, Krøyer A, Hove H, et al. Educational delay and attainment in persons with neurofibromatosis 1 in Denmark. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27:857–68.

Johansson E, Kallionpää RA, Böckerman P, Peltonen J, Peltonen S. A rare disease and education: Neurofibromatosis type 1 decreases educational attainment. Clin Genet. 2021;99:529–39.

Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:91–94.

Andersen KK, Duun-Henriksen AK, Frederiksen MH, Winther JF. Ninth grade school performance in Danish childhood cancer survivors. Br J Cancer. 2017;116:398–404.

Lindahl M, Addington SV, Winther JF, Schmiegelow K, Andersen KK. Socioeconomic factors and ninth grade school performance in childhood leukemia and CNS tumor survivors. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2:1–8.

International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 1997. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 2006. www.uis.unesco.org.

Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:103–5.

Documentation of statistics for immigrants and descendants. Copenhagen: Danmarks Statistik; 2017. http://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/dokumentation/documentationofstatistics/immigrants-and-descendants.

Solheim OJ, Lunetræ K. Can test construction for varying gender differences in international reading achievement tests of children, adolescents and young adults? – A study based on Nordic results in PIRLS, PISA amd PIAAC. Assess Educ: Princ Policy Pract. 2018;25:107–26.

Huurre T, Aro H, Rahkonen O, Komulainen E. Health, lifestyle, family and school factors in adolescence: predicting adult educational level. Educ Res. 2006;48:41–53.

Erola J, Jalonen S, Lehti H. Research in social stratification and mobility, parental education, class and income over early life course and children’s achievement. Res Soc Stratif Mobil. 2016;44:33–43.

Descheemaeker MJ, Ghesquière P, Symons H, Fryns JP, Legius E. Behavioural, academic and neuropsychological profile of normally gifted Neurofibromatosis type 1 children. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2005;49:33–46.

Naglieri JA, Prewett PN, Bardos AN. An exploratory study of planning, attention, simultaneous, and successive cognitive processes. J Sch Psychol. 1989;27:347–64.

Blair C, Diamond A. Biological processes in prevention and intervention. The promotion of self regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:899–911.

Krab LC, Aarsen FK, de Goede-Bolder A, Catsman-Berrevoets CE, Arts WF, Moll HA, et al. Impact of neurofibromatosis type 1 on school performance. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:1002–10.

Coudé FX, Mignot C, Lyonnet S, Munnich A. Early grade repetition and inattention associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Atten Disord. 2007;11:101–5.

Lorenzo J, Barton B, Arnold SS, North KN. Cognitive features that distinguish preschool-age children with neurofibromatosis type 1 from their peers: a matched case-control study. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1479–83.

Garg S, Lehtonen A, Huson SM, Emsley R, Trump D, Evans DG, et al. Autism and other psychiatric comorbidity in neurofibromatosis type 1: Evidence from a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:139–45.

Ramtekkar UP, Reiersen AM, Todorov AA, Todd RD. Sex and age differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and diagnoses: implications for DSM-V and ICD-11. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:217–28.

Houlberg K, Andersen VN, Bjørnholt B, Krassel KF, Pedersen LH. Country Background Report – Denmark OECD review of policies to improve the effectiveness of resource use in schools. KORA. 2016. Available at https://www.oecd.org/education/school/10932_OECD%20Country%20Background%20Report%20Denmark.pdf.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully dedicate this paper to the respected memory of Dr Sven Asger Sørensen, MD, DMSc (1936–2021). In the mid-1980s, he began the recontact and updating of a Danish national register of neurofibromatosis patients first assembled in the 1940s by A. Borberg. Dr Sørensen’s great contribution to the NF research made our current work feasible and possible.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from the Leo Foundation, under award no. LF-OC-19-000088. The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KD conceived and designed the study, coordinated data analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. FB carried out the analyses, interpreted results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. KKA conceived and designed the study, carried out data collection and the initial analysis, and reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. JM conceived and designed the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. JØ, HH, MMH, CE interpreted results and reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. LK and JFW conceived and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study is part of the NF1 research program ‘Life with NF1’, which was originally approved by the Danish Protection Agency (Record 2014–41–2935). With reference to the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the research project is listed in a local database (2018-DCRC-0012) at the Danish Cancer Society Research Center. The database provides an overview of ongoing research projects involving personal data under the GDPR and replaces the former notification from the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doser, K., Belmonte, F., Andersen, K.K. et al. School performance of children with neurofibromatosis 1: a nationwide population-based study. Eur J Hum Genet 30, 1405–1412 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01149-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01149-z

This article is cited by

-

Employment, occupation, and income in adults with neurofibromatosis 1 in Denmark: a population- and register-based cohort study

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2023)

-

The utility of population level genomic research

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

Virtual Reality Water Maze Navigation in Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and Reading Disability: an Exploratory Study

Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology (2022)