Abstract

A Guideline Group (GG) was convened from multiple specialties and patients to develop the first comprehensive schwannomatosis guideline. The GG undertook thorough literature review and wrote recommendations for treatment and surveillance. A modified Delphi process was used to gain approval for recommendations which were further altered for maximal consensus. Schwannomatosis is a tumour predisposition syndrome leading to development of multiple benign nerve-sheath non-intra-cutaneous schwannomas that infrequently affect the vestibulocochlear nerves. Two definitive genes (SMARCB1/LZTR1) have been identified on chromosome 22q centromeric to NF2 that cause schwannoma development by a 3-event, 4-hit mechanism leading to complete inactivation of each gene plus NF2. These genes together account for 70–85% of familial schwannomatosis and 30–40% of isolated cases in which there is considerable overlap with mosaic NF2. Craniospinal MRI is generally recommended from symptomatic diagnosis or from age 12–14 if molecularly confirmed in asymptomatic individuals whose relative has schwannomas. Whole-body MRI may also be deployed and can alternate with craniospinal MRI. Ultrasound scans are useful in limbs where typical pain is not associated with palpable lumps. Malignant-Peripheral-Nerve-Sheath-Tumour-MPNST should be suspected in anyone with rapidly growing tumours and/or functional loss especially with SMARCB1-related schwannomatosis. Pain (often intractable to medication) is the most frequent symptom. Surgical removal, the most effective treatment, must be balanced against potential loss of function of adjacent nerves. Assessment of patients’ psychosocial needs should be assessed annually as well as review of pain/pain medication. Genetic diagnosis and counselling should be guided ideally by both blood and tumour molecular testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schwannomatosis is an inherited syndrome characterised by the development of typically painful, benign nerve-sheath tumours (schwannomas) on the spinal and peripheral nerves around the body [1, 2]. Cranial nerves are affected to a lesser extent and there is characteristic sparing of the 8th cranial nerve, which is the most commonly affected by schwannomas in sporadic/isolated non-hereditary cases and in neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) [1, 2]. Intradermal schwannomas are characteristic lesions in NF2 and are absent in schwannomatosis. Vestibular schwannomas may occur in around 10% of LZTR1-related schwannomatosis patients but do not seem to occur at any increased frequency in other types of schwannomatosis.

The ‘term’ schwannomatosis appears to date from the 1950s, but other terms such as neurilemmomatosis have also been coined. The early literature is confused as both schwannomatosis and neurilemmomatosis were terms used in Japan to include patients who clearly had NF2 with bilateral vestibular schwannomas [3, 4]. Nevertheless, in the mid-1990s a consensus began to develop that the entity schwannomatosis was distinct from NF2 [5,6,7], although concern still existed over significant overlap with NF2 [8]. The molecular mechanism of schwannomatosis shows different somatic point mutations in NF2 between schwannomas in the same person [9]; linkage analysis in a number of families to exclude the NF2 locus on chromosome 22q [10] confirmed the existence of the separate entity. In 2007 a separate gene on chromosome 22 called SMARCB1 was found to cause a subset of familial and sporadic/isolated cases of schwannomatosis [11,12,13,14]. The gene was also linked in at least some families to a tendency to develop meningiomas [15], although this tumour is still relatively uncommon even in SMARCB1-related schwannomatosis [2, 16]. Seven years after identification of SMARCB1 as a causal entity, a second 22q gene LZTR1 was identified as a cause of schwannomatosis [17]. This again raised the overlap with NF2 as a number of cases developed unilateral vestibular schwannoma and met the Manchester diagnostic criteria for NF2 [18,19,20]. Furthermore, many sporadically affected individuals that do not have either LZTR1 or SMARCB1 germline pathogenic variants but meet schwannomatosis criteria [21, 22], have mosaic NF2 with identical pathogenic variants in two separate schwannomas [2, 20, 23, 24]. The overlap from both the vestibular schwannomas occurring in LZTR1-related schwannomatosis and mosaic NF2 mimicking schwannomatosis has necessitated a re-evaluation of the existing diagnostic criteria [25] and an international effort has defined new criteria that will be published in 2022.

The overriding feature in individuals with schwannomatosis is pain, with little if any neurological deficit [1]. Removal of schwannomas often results in complete resolution of pain symptoms [1]. Life expectancy is not usually reduced, unlike in NF2 [2], but quality of life is strongly affected. Whilst there exists some concern over malignant potential in SMARCB1-related schwannomatosis [26, 27], this does not appear to be a feature of other types of schwannomatosis. Other common features of NF2 such as ependymomas and ocular features such as retinal hamartoma, epiretinal folds and juvenile cataracts have not been reported in schwannomatosis [1, 2]. Until now only a guideline for children and young adults has been published [28]. Overall, SMARCB1/LZTR1 have been shown to account for 70–85% of familial schwannomatosis and 30–40% of isolated cases in which there is considerable overlap with mosaic NF2. It is likely that at least one other gene/mechanism exists to explain 22q related schwannomatosis as well as at least a minority of cases caused by a non 22q mechanism.

Scope of the guideline

This guideline is intended to define the optimal diagnosis, clinical management and surveillance of people with a confirmed diagnosis of schwannomatosis and has been elaborated by members of the European Reference Network (ERN) for Genetic Tumour Risk Syndromes (GENTURIS).

It aims specifically to integrate available information to assist healthcare professionals in the identification and clinical management and surveillance of people with schwannomatosis. These guidelines do not signify nor intend to be a legal standard of care, they should support clinical decision making, but never replace clinical professionals.

Methods

The ERN GENTURIS schwannomatosis Guideline Group (GG) consists of clinicians with expertise from clinical genetics, (neuro-, peripheral nerve) surgery, dermatology, anaesthesiology, neurology, radiology, and affected individuals and their representatives. The GG was led by a Core Working Group of ERN GENTURIS Healthcare Provider (HCP) Members from different Member States and who are recognised experts in specialised clinical practice in the diagnosis and management of schwannomatosis. A Patient Advisory Group was established and included 4 affected individuals that have experience with schwannomatosis.

The guideline was developed based on 237 published articles extracted from PubMed, using the following terms: schwannomatosis [title/abstract].

Additional papers were requested from experts in the field and references of all the papers were considered. Papers were included if they contained any data on diagnosis, treatment, management or surveillance of people with schwannomatosis.

As is typical for many rare diseases, the volume of peer-reviewed evidence available to consider for these guidelines was small and came from a limited number of articles, which typically reported on small samples or series. To balance the weight of both published evidence and quantify/wealth of expert experience and knowledge, we have used the following scale to grade the recommendation: (i) strong evidence: Expert consensus AND consistent evidence; (ii) moderate evidence: Expert consensus WITH inconsistent evidence AND/OR new evidence likely to support the recommendation, and (iii) weak evidence: Expert majority decision WITHOUT consistent evidence. Expert consensus (an opinion or position reached by a group as whole) or expert majority decision (an opinion or position reached by the majority of the group) is established after reviewing the results of the modified Delphi approach within the Core Working Group.

After drafting recommendations amongst the GG these were subjected to a modified Delphi assessment. Delphi is a structured communication technique or method in which opinions of a large number of experts are assessed on a topic in which there is no consensus, and this was used as a consensus building exercise. Experts included in this exercise included the members of the Core Working Group, the Schwannomatosis GG, the Patient Advisory Group, as well as other (external) experts identified by the GG.

The survey existed of four rounds, in which the threshold for consensus was defined by a simple majority of the survey participants agree with the recommendation (>60% rated ‘agree’ or ‘totally agree’). Recommendations were graded using a 4-point Likert scale (totally disagree, disagree, agree, totally agree) and a justification for the given rating was obligatory. Even if consensus was met recommendations were still modified if a higher consensus was thought achievable from written responses. The facilitator of the Delphi survey provided anonymised summaries of the experts’ decisions after each round as well as the reasons they provided for their judgements. The recommendations are presented in the Table 1.

Discussion

The schwannomatosis GG has developed recommendations for the diagnosis, surveillance and treatment of schwannomatosis in both children and adults with a high degree of consensus across clinical experts and patients. Recommendations are similar to, but distinct from a previous working group for the American Association of Cancer Research [28] which made recommendations for children and young adults. These differences are partly based on subsequent publications, but also on the need to simplify the gene-based recommendations as the childhood onset differences between LZTR1-related schwannomatosis and SMARCB1-related schwannomatosis are not striking. The present guideline has developed more comprehensive recommendations for treatment especially of the hallmark symptom of pain. Recommendations regarding surveillance are tempered by the need not to overburden patients with unnecessary MRI scans particularly as some schwannomatosis patients are mildly affected and may produce only a very small number of symptomatic schwannomas in their lifetime. We have also recognised that in an era of increasing large gene panel testing, exome and genome screening that ‘incidental’ presumed pathogenic variants in particular in LZTR1 will be identified in individuals with no family history or suggestive personal history of schwannomatosis. Overall, the frequency of presumed loss of function variants in LZTR1 in the population database gnomAD is ~1 in 310. Whereas the frequency of confirmed LZTR1-related schwannomatosis based on a birth incidence of schwannomatosis of 1 in 69,000 and the fact that around 27–30% of schwannomatosis cases are caused by LZTR1 [2] is less than 1 in 227,000, This means that <1% of those individuals with no family history or suggestive personal history of schwannomatosis and carrying a potential pathogenic LZTR1 variant are likely to develop schwannomatosis. This contrasts with a 50% likelihood of inheriting a disease associated variant in offspring of people with schwannomatosis and a pathogenic variant in LZTR1. Nonetheless, several cases of incomplete penetrance have also been observed for this gene even within families with confirmed cases [17, 18, 20, 24, 29,30,31], although the penetrance is not yet determined it may be in the region of 40–50%. Penetrance appears higher in SMARCB1 and Loss of Function variants are much less common in population databases. As such we have not recommended surveillance in individuals with ‘incidental’ findings of an LZTR1 variant. Genetic counselling should be guided ideally by both blood and tumour molecular testing to aid discussion of transmission risks. This should also address uncertainties around disease penetrance as well as informing about reproductive options.

Malignancy is thought to occur rarely in schwannomatosis. Recently several cases have been described mainly in patients harbouring germline mutations in SMARCB1 gene. A clear increased risk of a malignant-peripheral nerve-sheath tumour has been established [26] although it is possible that a more extended malignancy phenotype associated with a SMARCB1 pathogenic variant does exist [27]. Due to this increased risk, we have recommended that a changing tumour, in someone with SMARCB1 germline pathogenic variant, especially one causing functional impairment, should prompt exclusion of malignant transformation.

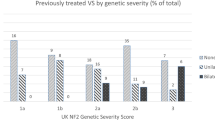

Clinically, schwannomatosis is distinguished from NF2 by the absence of bilateral vestibular schwannomas and ependymomas [2, 25]. Previously, a vestibular schwannoma was considered an exclusion criterion for schwannomatosis [32]. However, the identification of LZTR1 as a cause of schwannomatosis reduces the specificity of these more inclusive criteria and even the presence of bilateral VS is now no longer sufficient to be certain that an individual has NF2 [18, 20], although draft international consensus guidelines have retained bilateral VS as diagnostic for NF2. Furthermore, LZTR1 germline pathogenic variants have been recently associated with higher risk of Unilateral Vestibular Schwannomas [19]. Therefore, the GG recommended that unilateral vestibular schwannomas should not be considered an exclusion criterion for the diagnosis of schwannomatosis in the absence of proven germline or mosaic NF2 [2, 25].

Segmental schwannomatosis is characterised by multiple schwannomas affecting one-limb or less than 5 contiguous segments of spine. The incidence of segmental forms among schwannomatosis patients remains to be determined precisely but has been reported as high as 30% in some series (27 out of 87 patients [33]). The genetics of segmental schwannomatosis remains incompletely understood with the description of germline LZTR1 pathogenic variants in 33% [34] to 40% [35] of patients. Those findings suggest that segmental schwannomatosis might be different from a presumed somatic mosaicism.

Surgical resection of tumours seems to be effective on pain control in segmental schwannomatosis patients [34], but is characterised by a high rate of recurrence (5/9, 55% [34]), or by the systematic appearance of new tumours (4/4, 100% [36]). After surgery, neurological deficit seems to be more frequent than in sporadic cases, presumably due to the presence of several contiguous tumours in the same nerve, mimicking a rosary, but, in general, transient and clinical symptoms disappear in the month following surgery [36]. The GG recommendations reflect this.

Lastly, we have specifically included the psychological needs of patients who often have intractable pain that can hugely affect quality of life. Although schwannomatosis does not appear to affect life expectancy [2] it could be associated with an important emotional impact, including suicide, therefore the GG recommended assessment of psychological needs at annual visits.

There is clearly need for future research in schwannomatosis. A clear need is the development of better pain medication. The reason(s) why so few people who carry loss of function variants in LZTR1 develop schwannomatosis is another important area for research as well as better prediction of MPNST risk and early detection. There is also a need to clarify the overlap with allelic conditions such as LZTR1-related Noonan syndrome as well as Coffin-Siris and rhabdoid tumour predisposition with SMARCB1 variants. The latter also creates issues with incidental findings particularly in neonates or very young children [28, 37]. Genotype phenotype correlations are nonetheless strong with only minor overlap between rhabdoid predisposition and schwannomatosis with SMARCB1 [37, 38].

In summary we have produced consensus recommendations for people affected or at risk of schwannomatosis that had high levels of agreement through four rounds of Delphi amongst a large peripatetic expert and patient group.

Website

The complete guidelines can be downloaded from the ERN website: https://www.genturis.eu.

Disclaimer

The content of these guidelines represents the views of the authors only and it is their sole responsibility; it cannot be considered to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) or any other body of the European Union. The European Commission and the Agency do not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

References

Dhamija R, Plotkin S, Asthagiri A, Messiaen L, Babovic-Vuksanovic D. Schwannomatosis. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, et al. editors. GeneReviews((R)). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.; 1993.

Evans DG, Bowers NL, Tobi S, Hartley C, Wallace AJ, King AT, et al. Schwannomatosis: a genetic and epidemiological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:1215–9.

Matsuo A, Tooyama I, Akiguchi I, Kimura J, Kameyama M. A case of schwannomatosis–clinical, pathological and biochemical studies. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1991;31:742–5.

Iwabuchi S, Tanita T, Koike K, Fujimura S. Familial neurilemmomatosis: report of a case. Surg Today. 1993;23:816–9.

MacCollin M, Woodfin W, Kronn D, Short MP. Schwannomatosis: a clinical and pathologic study. Neurology. 1996;46:1072–9.

Pulst SM, Riccardi V, Mautner V. Spinal schwannomatosis. Neurology. 1997;48:787–8.

Wolkenstein P, Benchikhi H, Zeller J, Wechsler J, Revuz J. Schwannomatosis: a clinical entity distinct from neurofibromatosis type 2. Dermatology. 1997;195:228–31.

Evans DG, Mason S, Huson SM, Ponder M, Harding AE, Strachan T. Spinal and cutaneous schwannomatosis is a variant form of type 2 neurofibromatosis: a clinical and molecular study. J Neurol Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1997;62:361–6.

Jacoby LB, Jones D, Davis K, Kronn D, Short MP, Gusella J, et al. Molecular analysis of the NF2 tumor-suppressor gene in schwannomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:1293–302.

MacCollin M, Willett C, Heinrich B, Jacoby LB, Acierno JS Jr., Perry A, et al. Familial schwannomatosis: exclusion of the NF2 locus as the germline event. Neurology. 2003;60:1968–74.

Hulsebos TJ, Plomp AS, Wolterman RA, Robanus-Maandag EC, Baas F, Wesseling P. Germline mutation of INI1/SMARCB1 in familial schwannomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:805–10.

Boyd C, Smith MJ, Kluwe L, Balogh A, Maccollin M, Plotkin SR. Alterations in the SMARCB1 (INI1) tumor suppressor gene in familial schwannomatosis. Clin Genet. 2008;74:358–66.

Hadfield KD, Newman WG, Bowers NL, Wallace A, Bolger C, Colley A, et al. Molecular characterisation of SMARCB1 and NF2 in familial and sporadic schwannomatosis. J Med Genet. 2008;45:332–9.

Sestini R, Bacci C, Provenzano A, Genuardi M, Papi L. Evidence of a four-hit mechanism involving SMARCB1 and NF2 in schwannomatosis-associated schwannomas. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:227–31.

Christiaans I, Kenter SB, Brink HC, van Os TA, Baas F, van den Munckhof P, et al. Germline SMARCB1 mutation and somatic NF2 mutations in familial multiple meningiomas. J Med Genet. 2011;48:93–7.

Hadfield KD, Smith MJ, Trump D, Newman WG, Evans DG. SMARCB1 mutations are not a common cause of multiple meningiomas. J Med Genet. 2010;47:567–8.

Piotrowski A, Xie J, Liu YF, Poplawski AB, Gomes AR, Madanecki P, et al. Germline loss-of-function mutations in LZTR1 predispose to an inherited disorder of multiple schwannomas. Nat Genet. 2014;46:182–7.

Smith MJ, Isidor B, Beetz C, Williams SG, Bhaskar SS, Richer W, et al. Mutations in LZTR1 add to the complex heterogeneity of schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2015;84:141–7.

Pathmanaban ON, Sadler KV, Kamaly-Asl ID, King AT, Rutherford SA, Hammerbeck-Ward C, et al. Association of genetic predisposition with solitary schwannoma or meningioma in children and young adults. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:1123–9.

Smith MJ, Bowers NL, Bulman M, Gokhale C, Wallace AJ, King AT, et al. Revisiting neurofibromatosis type 2 diagnostic criteria to exclude LZTR1-related schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2017;88:87–92.

MacCollin M, Chiocca EA, Evans DG, Friedman JM, Horvitz R, Jaramillo D, et al. Diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2005;64:1838–45.

Plotkin SR, Blakeley JO, Evans DG, Hanemann CO, Hulsebos TJ, Hunter-Schaedle K, et al. Update from the 2011 International Schwannomatosis Workshop: From genetics to diagnostic criteria. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161a:405–16.

Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Kluwe L, Friedrich RE, Summerer A, Schäfer E, Wahlländer U, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic overlap between mosaic NF2 and schwannomatosis in patients with multiple non-intradermal schwannomas. Hum Genet. 2018;137:543–52.

Louvrier C, Pasmant E, Briand-Suleau A, Cohen J, Nitschké P, Nectoux J, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing for differential diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 2, schwannomatosis, and meningiomatosis. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:917–29.

Evans DG, King AT, Bowers NL, Tobi S, Wallace AJ, Perry M, et al. Identifying the deficiencies of current diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis 2 using databases of 2777 individuals with molecular testing. Genet Med. 2019;21:1525–33.

Evans DG, Huson SM, Birch JM. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in inherited disease. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2012;2:17.

Eelloo JA, Smith MJ, Bowers NL, Ealing J, Hulse P, Wylie JP, et al. Multiple primary malignancies associated with a germline SMARCB1 pathogenic variant. Fam Cancer. 2019;18:445–9.

Evans DGR, Salvador H, Chang VY, Erez A, Voss SD, Druker H, et al. Cancer and central nervous system tumor surveillance in pediatric neurofibromatosis 2 and related disorders. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:e54–61.

Hutter S, Piro RM, Reuss DE, Hovestadt V, Sahm F, Farschtschi S, et al. Whole exome sequencing reveals that the majority of schwannomatosis cases remain unexplained after excluding SMARCB1 and LZTR1 germline variants. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:449–52.

Paganini I, Chang VY, Capone GL, Vitte J, Benelli M, Barbetti L, et al. Expanding the mutational spectrum of LZTR1 in schwannomatosis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:963–8.

Paganini I, Sestini R, Cacciatore M, Capone GL, Candita L, Paolello C, et al. Broadening the spectrum of SMARCB1-associated malignant tumors: a case of uterine leiomyosarcoma in a patient with schwannomatosis. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:1226–31.

Baser ME, Friedman JM, Evans DG. Increasing the specificity of diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2006;66:730–2.

Merker VL, Esparza S, Smith MJ, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Plotkin SR. Clinical features of schwannomatosis: a retrospective analysis of 87 patients. Oncologist. 2012;17:1317–22.

Alaidarous A, Parfait B, Ferkal S, Cohen J, Wolkenstein P, Mazereeuw-Hautier J. Segmental schwannomatosis: characteristics in 12 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14:207.

Farschtschi S, Mautner VF, Pham M, Nguyen R, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Hutter S, et al. Multifocal nerve lesions and LZTR1 germline mutations in segmental schwannomatosis. Ann Neurol. 2016;80:625–8.

Chick G, Victor J, Hollevoet N. Six cases of sporadic schwannomatosis: Topographic distribution and outcomes of peripheral nerve tumors. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2017;36:378–83.

Foulkes WD, Kamihara J, Evans DGR, Brugières L, Bourdeaut F, Molenaar JJ, et al. Cancer surveillance in gorlin syndrome and rhabdoid tumor predisposition syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:e62–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0595.

Smith MJ, Wallace AJ, Bowers NL, Eaton H, Evans DG. SMARCB1 mutations in schwannomatosis and genotype correlations with rhabdoid tumors. Cancer Genet. 2014;207:373–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cancergen.2014.04.001.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Manon Engels, Matt Bolz-Johnson and Tom Kenny for logistic support, coordination of the guideline committee meetings and facilitating the guideline development process. They also acknowledge their colleagues from the ERN GENTURIS for fruitful discussions and suggestions. A special thanks to all the (external) experts who had participated in the modified Delphi assessment: Helen Hanson1, Miriam J. Smith2, Amy Taylor3, Eva Trevisson4, Monique Anten5, Said Chosro Farschtschi6, C. Oliver Hanemann7, Victor Mautner6, Ciaran Bolger8, Frank van Calenbergh9, Bernhard Frank10. 1St Georges University Hospital’s NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom; 2The University of Manchester, United Kingdom; 3Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom; 4University of Padova, Italy; 5Maastricht UMC+, the Netherlands; 6University Medical Centre Hamburg Eppendorf, Germany; 7Peninsula Medical School, Brain Tumour Centre, Plymouth, United Kingdom; 8Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Beaumont Hospital, Ireland; 9University hospital Leuven—Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium; 10The Walton Centre NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, United Kingdom.

Funding

This guideline has been supported by the ERN GENTURIS—Project ID No. 739547. ERN GENTURIS is partly co-funded by the European Union within the framework of the Third Health Programme ‘ERN-2016—Framework Partnership Agreement 2017–2021’. DGE is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) BRC Manchester (Grant Reference Number 1215-200074).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The schwannomatosis GG consisted of DP, MF, MPi, NC, PW, NT, RF, MK, MPe, LP, EL, JLB, AK, CD, SS, including the Core Working Group consisting of IB, SM, and DGE. These individuals drafted recommendations and agreed the final ones after Delphi. The schwannomatosis GG as well as HH, MJS, AT, ET, MA, SCF, COH, VM, CB, FvC, BF participated in Delphi. All listed authors commented on drafts and agreed the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors of the ERN GENTURIS guideline have provided disclosure statements on all relationships that they have that might be perceived to be a potential source of a competing interests. DGE and RF report receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from AstraZeneca. MK and DGE report receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from Recursion. DGE and EL report receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from Springworks Therapeutics. LP reported receipt of grants/research support from Devyser. NT reports participation in a company sponsored speaker’s bureau from Stryker. DP reports reimbursement of travel expenses for medical conferences by Medtronic and Nevro Corp. All participants of the ERN GENTURIS schwannomatosis Delphi survey have provided disclosure statements on all relationships that they have that might be perceived to be a potential source of a competing interests. HH report receipt of honoraria or consultation fees from Pfizer. BF reports receipt of honoraria from Gruenenthal UK and Gruenenthal Europe.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, D.G., Mostaccioli, S., Pang, D. et al. ERN GENTURIS clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment, management and surveillance of people with schwannomatosis. Eur J Hum Genet 30, 812–817 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01086-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01086-x

This article is cited by

-

Surgical management of sporadic and schwannomatosis-associated pelvic schwannomas

Neurosurgical Review (2023)

-

Management of Central and Peripheral Nervous System Tumors in Patients with Neurofibromatosis

Current Oncology Reports (2023)

-

Beitrag der Humangenetik zur Präzisionsonkologie

Die Onkologie (2023)

-

Clinical genomics testing: mainstreaming and globalising

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)