Abstract

Reproductive genetic carrier screening (RGCS) may be offered to all individuals and couples, regardless of family history or ethnicity. “Mackenzie’s Mission” (MM) is an Australian RGCS pilot study, evaluating the offer of couple-based screening for ~1300 genes associated with around 750 autosomal and X-linked recessive childhood-onset conditions. Each member of the couple makes an individual decision about RGCS and provides consent. We developed a decision aid (RGCS-DA) to support informed decision-making in MM, suitable for couples who were either non-pregnant or in early pregnancy. A Delphi approach invited experts to review values statements related to various concepts of RGCS. Three review rounds were completed, seeking consensus for relevance and clarity of statements, incorporating recommended modifications in subsequent iterations. The final RGCS-DA contains 14 statements that achieved Delphi consensus plus the attitude scale of the measure of informed choice. This was then evaluated in cognitive talk aloud interviews with potential users to assess face and content validity. Minimal wording changes were required at this stage. After this process, the RGCS-DA was piloted with 15 couples participating in MM who were then interviewed about their decision-making. The RGCS-DA prompted discussion within couples and facilitated in depth consideration of screening. There was reassurance when values aligned and a sense of shared decision-making within the couple. This RGCS-DA may become a very useful tool in supporting couples’ decision making and contribute to RGCS being feasible for scaled-up implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research and policy statements by professional bodies recommend that reproductive genetic carrier screening (RGCS) be offered to all individuals and couples, regardless of family history [1,2,3,4,5].

These statements were developed against a background of advances in genomic testing technologies that facilitate simultaneous screening for carrier status of many conditions. Whilst this screening was initially available for individual genetic conditions, now gene panels covering multiple conditions, ranging from a small number of genes to hundreds of gene, exist [6, 7]. Such screening has sometimes been referred to as expanded genetic carrier screening and will be referred to here as reproductive genetic carrier screening (RGCS). RGCS is now available through government funded testing, commercial providers or research studies in a number of countries [8,9,10,11].

The Australian Reproductive Genetic Carrier Screening Program (ARGCSP), also known as “Mackenzie’s Mission” (MM), is a research study evaluating the offer of screening for ~1300 genes associated with around 750 autosomal and X-linked recessive childhood-onset conditions [12].

The gene selection committee, an interdisciplinary group including clinicians, laboratory scientists, genetic counselors, a consumer representative, and a bioethicist, evaluated conditions for inclusion. The committee drew on a number of indicators; that the condition had an onset in childhood, that the condition would have a serious impact on a person’s quality of life and/or be life limiting, technical feasibility, whether there were heterozygote phenotypes, community considerations and strength of evidence for gene-phenotype relationship. Underpinning this was consideration as to whether an “average” couple would take steps to avoid the birth of a child with the genetic condition.

It is important to recognize that several of these indicators are subject to ongoing consideration and debate, including how the notion of “serious” or “severe” should be defined and approached in practice [13, 14]. The gene list in the MM study is revised periodically and is being formally evaluated.

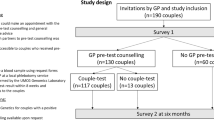

The MM study uses a simultaneous screening approach, previously shown to be acceptable, and reports a combined result relevant for the reproductive couple being tested [15]. In recognizing there is diversity in composition of families, we use the term “reproductive couple” to refer to the two individuals who are or will be the biological/genetic parents for the planned or current pregnancy. Individual carrier results are only reported in the case of X-linked conditions. Intended genetic parents (hereafter referred to as couples) are invited to participate in the study by their healthcare provider. If they wish to take part, they are given a unique access code to each log into the study website and complete their individual enrollment online (www.mackenziesmisson.org.au). Participating couples each provide demographic information and complete an education module about RGCS. The website education module provides information about genetics and inheritance, RGCS process and limitations, screening outcomes and reproductive options. Via the study website, couples can also access an optional decision aid (DA). Each member of the couple must make an individual decision about whether or not to have RGCS. The screening test will only proceed once both members have provided consent.

RCGS is generally offered in both preconception and prenatal healthcare settings. Preconception genetic carrier screening facilitates reproductive decision making for future parents, giving rise to a range of reproductive options, including preimplantation genetic testing (PGT). However, RCGS is more commonly accessed in early pregnancy when couples are seeking prenatal healthcare services [16]. A key challenge in delivering RGCS is ensuring that those offered screening have opportunity to make an informed decision about accessing screening.

Psychosocial risks arising from lack of informed decision making for RGCS have been previously identified, including poor understanding of potential results, stress and anxiety, and decision making that does not align with the individual’s values [10]. There are also ethical concerns, including the influence of socially constructed models of disability and difference and the individualization of decision-making [13, 17].

DAs have been shown to support decision making for RCGS, prenatal testing and other genomic testing [18,19,20]. Here we describe the development of a DA (the RGCS-DA) designed to support decision making in the MM program.

Materials (subjects) and methods

This study has Human Research Ethics Committee approval (The Royal Children’s Hospital, 2019.097_V3).

This methods section describes (1) the development of the RGCS-DA; and (2) pilot use of the RGCS-DA within the MM program.

Development of the RGCS-DA

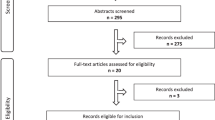

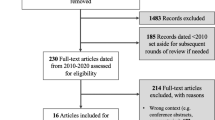

The RGCS-DA was developed using a systematic process according to the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration checklist (IPDASi) [21]; an overview is shown in Fig. 1. The IPDASi describes the minimum standards for certification of DAs required to reduce harmful bias and can be used to assess DA quality and content validity during development. There are three categories of criteria in the IPDASi: (i) qualifying; (ii) certification; and (iii) quality. Qualifying criteria (six criteria required to qualify as a DA) and certification criteria (ten criteria required to reduce harmful bias) are both mandatory. Quality criteria (28 criteria to enhance the DA) are desired but non-essential. See Table 1 footnote for further detail of these criteria.

Figure 1 describes the development of the RGCS-DA. The initial draft of the RGCS-DA was created by adapting an existing prenatal screening DA [22]. The prenatal DA followed the Ottawa Decision support framework [23] and was developed using focus groups with general practitioners and people offered screening. It was piloted and then evaluated in a randomized control trial [24]. To adapt this prenatal DA for relevance to couples’ decision making in the context of RGCS, study-specific statements were drafted with input from the MM Education and Engagement Committee (Committee membership list is available at the following website https://www.mackenziesmission.org.au/our-team/) whose members are genetic counselors, clinical geneticists, educators, health professionals and researchers. The draft statements aligned with the educational materials available to couples on the study website, with the goal to prompt individuals to evaluate this information in line with their values. The attitude questions from the measure of informed choice developed by Marteau and colleagues were also included [25].

The RGCS-DA was then reviewed by invited experts using a modified, reactive Delphi process in three iterative rounds as described below and in Fig. 1. In a traditional Delphi process, experts generate content then refine it over subsequent rounds whereas in a modified, reactive Delphi process, experts review previously generated content [26].

Delphi participants

Delphi participants were experts purposively recruited from the MM committees and professional networks, representing several stakeholder groups. Experts completed their Delphi review rounds using surveys in REDCap; an online electronic data capture system hosted at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute [27]. Consensus on relevance and clarity of a DA statement was defined as 80% agreement, based on previously described Delphi consensus levels ranging from 70% to 80% [27,28,29]. If there was <80% agreement for either relevance or clarity, amended statements were again presented back to the group for review.

Delphi rounds

In Round 1 (R1), experts reviewed each statement and the rationale for the statement’s inclusion in the draft DA submitted to the Delphi group. Each statement rationale was written by Delphi convenors JH and EK (Table 1). Delphi experts were asked to rate the relevance and clarity of each statement on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree). Experts could suggest edits to statements and propose additional statements if desired. Statements for which consensus (strongly agree and agree) was achieved were immediately included in the final RGCS-DA and were removed from subsequent Delphi rounds. In Round 2 (R2), experts reviewed the aggregated feedback from the previous round for statements lacking consensus. They also reviewed any new or amended statements for relevance and clarity. In the last round (Round 3), experts reviewed the remaining statements with collated feedback where consensus had not yet been reached.

Cognitive interviews with potential users to evaluate face and content validity

Genetic support group representatives and people known to the MM program team who either had a lived experience of a genetic condition and/or were representative of the potential target group for the MM program were purposively sampled and invited to review the RGCS-DA for face and content validity (Fig. 1). Face validity assessed if the DA seemed suitable to the target audience and content validity measured the extent to which the DA included all aspects of decision-making for RGCS [30]. Participants were asked to complete the RGCS-DA during a cognitive talk-aloud interview and provide verbal feedback [31]. This feedback was discussed by authors EK and JH, and incorporated into the final DA.

Pilot of the RGCS-DA

Couples were enrolled in a pilot phase of the MM program from December 2019 to February 2020. A sub-set of these pilot program participants were invited to be interviewed (~30 min). A semi-structured interview guide was used to elicit their experience of enrolling in the MM program, motivation for taking part and their decision making about carrier screening, including use of the RGCS-DA.

Interview analysis

Telephone interviews were conducted by authors AA and BM. Audio-recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim, checked for accuracy and the transcripts were co-coded using inductive content analysis by authors EK, BM and JH [32]. The interview guide informed the initial coding framework with new codes added in an iterative, inductive process which included reading and re-reading the transcripts. Similarities and differences in the experiences of participants were compared using constant comparison and emergent concepts were regularly discussed between coders [33]. NVivo [34] was used to organize the data and manage coding.

Results

Development of the RGCS-DA

Delphi experts: recruitment and characteristics

Twelve experts participated in the Delphi review: five representatives from the MM education and engagement subcommittee included genetic counselors and general practitioners; five research representatives included implementation scientists, bioethicists and psychosocial researchers; a reviewer external to the MM program with expertize in reproductive genetics research, Delphi studies and DAs; and one consumer, a parent of a child with an autosomal recessive genetic condition.

Outcomes of the Delphi review rounds

Table 1 summarizes the RGCS-DA concepts with rationale for inclusion and mapping of statements to the IPDASi criteria. Outcomes for each statement following each Delphi round are shown including percentages of consensus and any changes to statements prior to inclusion in subsequent rounds.

As shown in Table 1, after Round 1, consensus was reached on both clarity and relevance for one statement (#10); relevance only for 10 statements (#s1, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16); and consensus was not achieved for relevance and/or clarity for three statements, two of which were modified (#s 14, 17) and one of which was removed (#4). Three new statements were suggested from the Delphi group to address: value of screening results (statement 2), value of genetic information to self (statement 3) and residual risk (statement 7).

In Round 2, the experts reached consensus for relevance and clarity for nine amended statements (#s1, 6, 8, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17). Five statements remained unresolved for relevance and/or clarity and further modifications were suggested (#s2, 3, 7, 9, 14) to be reviewed in the final round. Consensus was not reached for statement 5 and qualitative feedback unanimously excluded the statement, so it was removed.

In Round 3, the experts reviewed five remaining unresolved statements with collated feedback from the previous round, and explanatory text for the DA.

Throughout the review rounds, Delphi experts also provided qualitative feedback on the wording of statements; Table 2 provides an example of statement feedback and modifications throughout the rounds.

It was intended that the RGCS-DA would be completed by both early pregnant and non-pregnant couples in the MM program. Given this context, the Delphi experts commented that some of the statements may not be immediately relevant, such as termination of pregnancy for non-pregnant couples and PGT for pregnant couples. However, these concepts were thought by Delphi experts to be important considerations in the long-term implications of an increased chance result.

The final RGCS-DA contains 14 statements that achieved Delphi group consensus and the attitude scale of the measure of informed choice (Table 1, statement #10), [25] to support decision making for RGCS by prompting consideration of: the value and utility of the information gained by screening; approaches to decision making; testing and research requirements; uncertainty of and feelings about potential results; reproductive options; and types of conditions for which screening is available. Upon completion of the RGCS-DA, an overall score is generated which indicates whether the individual member of the couple is leaning towards or away from having RCGS. The RGCS-DA is available as Supplementary Materials; the scoring logic is available by request from the authors.

Development interviews – assessment of face and content validity by potential users

Six people participated in cognitive talk-aloud interviews [31]. These included: four who were genetic support group representatives from across Australian states and a couple (interviewed as individuals) planning a pregnancy. One member of this couple has a genetic condition. Feedback from these interviews led to minor wording changes for clarity and to ensure terminology was neutral in tone and engaging. For example, instructional text for the RGCS-DA initially read “If you do not feel you understand enough to make your decision right now, we recommend you go back through the education module”. One interview participant suggested framing the text to remove the negative connotations associated with needing to review the education material, such as embarrassment or shame. The text was amended to “You are welcome to review the education module at any time throughout the study”.

Qualitative evaluation of the RGCS-DA

To evaluate the use of the RGCS-DA, fifteen people who were enrolled in the MM program were interviewed and asked about their experience of completing the RGCS-DA as part of their enrollment into the MM program. Thirteen participants completed the optional RGCS-DA, while two did not complete it.

Overall, interviewees described the RGCS-DA as useful. It became obvious that some couples had already decided to have the screening before completing study enrollment, but they commented that they found that the RGCS-DA reinforced their decision and provided reassurance. They also reflected that it had facilitated discussion about their individual decision-making with their partner:

I thought I knew where I was at in terms of how I felt about the testing, but I think it was nice to have that reinforced with the tools. [No children, planning pregnancy <1 year, no family history].

I think that decision making tool is actually quite useful. And particularly if maybe both (members) of the couples aren’t on the exact same page. I think it may give a little bit of room to have a little bit more discussion about what they might be concerned about. [Two children, planning pregnancy <1 year, child with a genetic condition].

I think [my husband]’s a bit more passive and so sometimes you do worry that he’s influenced or might feel pressured…so it was nice to actually do that questionnaire (RGCS-DA) and just be reassured cause he did it separately and… when the scores came out the same it was very reassuring. [No children, planning pregnancy 1–3 years, no family history].

Some individuals commented that completing the RGCS-DA prompted them to think more deeply about the decision to have screening. They reported greater consideration of the potential outcomes of screening and increased awareness of potentially being carriers for a genetic condition:

Sometimes you don’t think about those particular questions when you’re talking about the initial stages of it…we spoke about those questions more in depth about what we would do if this, what would we do if that, which we’ve never spoken about prior. [No children, unsure of pregnancy plans, has a genetic condition].

Discussion

This paper describes the development and initial experiences of using a novel DA, the RGCS-DA, designed to support couple decision making for RGCS. The IPDASi criteria and a modified Delphi process were used to create content of the DA and preliminary evaluation was done through pilot interviews. The RGCS-DA was incorporated into the MM participant website which also provides educational materials and a knowledge check for couples deciding about having RGCS.

The available commercial RGCS programs vary in the number of conditions screened and the mode of carrier testing for couples, i.e., sequential vs simultaneous or screening individuals only [8, 35]. The couple-based MM study presents a different environment for decision making, whereby both individual members in the couple independently complete an education module and can choose to use the RGCS-DA online. Together, they then can decide about preconception or prenatal RGCS for about 1300 genes.

Guidelines for genetic carrier screening programs highlight the need for informed decision making in this context [1, 3,4,5]. This is because RGCS can generate information that necessitates couples and XX carriers of X-linked conditions to reflect on both their values and their experiences of disability and difference. They may need to make complex decisions in regard to options like preparing for the birth of a child with a condition, PGT, or termination of pregnancy. It is therefore crucial that individuals can engage with the potential outcomes of screening in order to make a decision that aligns with their values. Overall, participants in this study reported positive experiences of using RGCS-DA, showing that it can enhance the decision-making process by affirming the way someone thinks about carrier screening, or by providing a platform for deliberation, encouraging discussion within a couple and taking the onus off the woman who often instigates reproductive genetic carrier screening [17].

There are many examples of DAs developed and evaluated using the IPDASi criteria, the gold standard methodology for assessing the quality of a DA. For example, a DA created by Beulen et al. [18] for use in the context of prenatal genetic testing included a web-based, multimedia DA that allowed for different levels of information to be explored by the user, based on their interest, prior knowledge, and time available. In a randomized controlled trial, the final IPDAS stage, this DA was found to be effective, augmenting routine prenatal testing care and ensuring women were making informed decisions, consistent with their attitudes towards prenatal testing. The development of other DAs in the genetic testing and reproductive choice contexts are published with examples including: the Genomics ADvISOR [20]; the Genomes and Pregnancy DA [19]; the Optional Results Choice Aid [36]; and an online DA to support reproductive decision making where a predisposition to cancer is known [37].

A strength of this RGCS-DA, robustly developed using IPDASi criteria, was its review via a modified Delphi process with experts who have experience providing clinical support to couples in decision making and/or undertake research on this topic. Therefore, appropriate coverage by the RGCS-DA of the complexities of decision making in this context were ensured. The RGCS-DA was planned for use by both pregnant and non-pregnant couples in MM and the Delphi review process guided the wording of statements that would be relevant and appropriate for couples in both situations. The conflicting feedback from Delphi experts across rounds also highlighted that, whilst issues such as termination of pregnancy should be sensitively addressed, it is crucial that individuals considering RGCS carefully consider their values on these issues. The Delphi experts agreed that it is necessary to use direct language to prompt reflection; the final RGCS-DA statements achieve this.

Our study had several limitations. While a range of experts participated in the Delphi process, there was only one consumer in the Delphi group. However, this was addressed by conducting face and content validity interviews with representatives and consumers during later stages of the RGCS-DA development.

It is important to note that the RGCS-DA has been developed to align with the MM study design. Thus, there are some aspects that may need to be adapted for other RGCS programs. For example, the grouping of conditions in MM may differ from other taxonomies, and there is evidence for variability in perceptions and definitions of “serious” [14, 38]. Nevertheless, this RGCS-DA is a useful tool to encourage deliberation in those contemplating screening and can be modified as practice and perspectives on carrier screening evolve. Ongoing evaluation of the use of the RGCS-DA, longitudinal quantitative and qualitative data collection of experiences and reproductive outcomes will be reported at the conclusion of the MM study.

To explore the experiences of early users of the RGCS-DA, interviews were conducted with people who participated in a pilot of the MM program. These pilot MM participants tended to already be engaged with the concept of RGCS due to previous personal experiences or family history of genetic conditions. Therefore, their views and experiences of using the RGCS-DA may not be representative of people who are offered RGCS and who have not encountered the concept of RGCS previously. We plan to further evaluate the use and perceived utility of the RGCS-DA within the MM program as it is rolled out throughout Australia.

Conclusion

We have seen, as reported by initial users, that the RGCS-DA complements education and counseling processes by encouraging greater consideration of and reflection on screening outcomes, and facilitates individual decision making within the context of a couple-based screening approach. Therefore, it may become a critical tool in supporting couples’ decision making as and when RGCS is offered at population scale. We await the conclusion of MM, following recruitment of ~8000 couples, to examine psychosocial outcomes for those who use the RGCS-DA and those who do not, but the pilot data presented here suggest that it may play a key, positive role in the decision-making process.

Disclosure

The Australian Reproductive Genetic Carrier Screening Project (Mackenzie’s Mission) is funded by the Australian Government’s Medical Research Future Fund as part of the Australian Genomics Health Futures Mission (GHFM), grant GHFM73390 (MRFF- G-MM). The grant is administered by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute through Australian Genomics. This work was supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

References

Henneman L, Borry P, Chokoshvili D, Cornel MC, van El CG, Forzano F, et al. Responsible implementation of expanded carrier screening. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:e1–12.

ACOG. Committee Opinion No. 690 summary: carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:595–6.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Genomics in general practice. East Melbourne, Vic, Australia: RACGP; 2020.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Genetic carrier screening (C-Obs 63). Melbourne, VIC: RANZCOG; 2019.

Gregg AR, Aarabi M, Klugman S, Leach NT, Bashford MT, Goldwaser T, et al. Screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions during pregnancy and preconception: a practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23:1793–806.

Robson SJ, Caramins M, Saad M, Suthers G. Socioeconomic status and uptake of reproductive carrier screening in Australia. Aust N. Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;60:976–9.

Archibald AD, Smith MJ, Burgess T, Scarff KL, Elliott J, Hunt CE, et al. Reproductive genetic carrier screening for cystic fibrosis, fragile X syndrome, and spinal muscular atrophy in Australia: outcomes of 12,000 tests. Genet Med. 2018;20:513–23.

Schuurmans J, Birnie E, van den Heuvel LM, Plantinga M, Lucassen A, van der Kolk DM, et al. Feasibility of couple-based expanded carrier screening offered by general practitioners. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27:691–700.

Cannon J, Van Steijvoort E, Borry P, Chokoshvili D. How does carrier status for recessive disorders influence reproductive decisions? A systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev Mol Diagnostics. 2019;19:1117–29.

Rowe CA, Wright CF. Expanded universal carrier screening and its implementation within a publicly funded healthcare service. J Community Genet. 2020;11:21–38.

Kauffman TL, Wilfond BS, Jarvik GP, Leo MC, Lynch FL, Reiss JA, et al. Design of a randomized controlled trial for genomic carrier screening in healthy patients seeking preconception genetic testing. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;53:100–5.

Kirk EP, Ong R, Boggs K, Hardy T, Righetti S, Kamien B, et al. Gene selection for the Australian reproductive genetic carrier screening project (“Mackenzie’s Mission”). Eur J Hum Genet. 2021;29:79–87.

Dive L, Newson AJ. Ethical issues in reproductive genetic carrier screening. Med J Aust. 2021;214:165–7 e1.

Boardman FK, Clark CC. What is a ‘serious’ genetic condition? The perceptions of people living with genetic conditions. Eur J Hum Genet. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-00962-2.

Plantinga M, Birnie E, Schuurmans J, Buitenhuis AH, Boersma E, Lucassen AM, et al. Expanded carrier screening for autosomal recessive conditions in health care: arguments for a couple-based approach and examination of couples’ views. Prenat Diagnosis. 2019;39:369–78.

Witt DR, Schaefer C, Hallam P, Wi S, Blumberg B, Fishbach A, et al. Cystic fibrosis heterozygote screening in 5,161 pregnant women. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:823–35.

Karpin IA. Protecting the future well: access to preconception genetic screening and testing and the right not to use it. Griffith Law Rev. 2016;25:71–86.

Beulen L, van den Berg M, Faas BHW, Feenstra I, Hageman M, van Vugt JMG, et al. The effect of a decision aid on informed decision-making in the era of non-invasive prenatal testing: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1409–16.

Halliday JL, Muller C, Charles T, Norris F, Kennedy J, Lewis S, et al. Offering pregnant women different levels of genetic information from prenatal chromosome microarray: a prospective study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:485–94.

Bombard Y, Clausen M, Mighton C, Carlsson L, Casalino S, Glogowski E, et al. The Genomics ADvISER: development and usability testing of a decision aid for the selection of incidental sequencing results. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:984–95.

Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, Durand MA, Sivell S, Stacey D, et al. Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids: a modified Delphi Consensus Process. Medical decision making: an international journal of the Society for. Med Decis Mak. 2014;34:699–710.

Nagle C, Lewis S, Meiser B, Metcalfe S, Carlin JB, Bell R, et al. Evaluation of a decision aid for prenatal testing of fetal abnormalities: a cluster randomised trial [ISRCTN22532458]. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:96.

Stacey D, Légaré F, Boland L, Lewis KB, Loiselle MC, Hoefel L, et al. 20th anniversary Ottawa Decision Support Framework: Part 3 overview of systematic reviews and updated framework. Med Decis Mak: Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 2020;40:379–98.

Nagle C, Gunn J, Bell R, Lewis S, Meiser B, Metcalfe S, et al. Use of a decision aid for prenatal testing of fetal abnormalities to improve women’s informed decision making: a cluster randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN22532458]. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;115:339–47.

Marteau TM, Dormandy E, Michie S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expectations: Int J Public Participation Health Care Health Policy. 2001;4:99–108.

McKenna HP. The Delphi technique: a worthwhile research approach for nursing? J Adv Nurs. 1994;19:1221–5.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81.

Paquette-Warren J, Tyler M, Fournie M, Harris SB. The Diabetes Evaluation Framework for Innovative National Evaluations (DEFINE): construct and content validation using a modified Delphi Method. Can J Diabetes. 2017;41:281–96.

Tognetto A, Michelazzo MB, Ricciardi W, Federici A, Boccia S. Core competencies in genetics for healthcare professionals: results from a literature review and a Delphi method. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:19.

Price P, Jhangiani R, Chiang I, Leighton D, Cuttler C. Reliability and Validity of Measurement in Research Methods in Psychology (3rd American Edition): The Saylor Foundation; 2017.

Czaja R, Blair J. Designing Surveys. Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press; 2005. Available from: http://methods.sagepub.com/book/designing-surveys.

Patton M. Qualitative research & evaluation methods USA: SAGE Publication Inc.; 2015.

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15:398–405.

NVivo. NVivo qualitative data analysis software. 12 ed: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2018.

Kauffman TL, Irving SA, Leo MC, Gilmore MJ, Himes P, McMullen CK, et al. The NextGen Study: patient motivation for participation in genome sequencing for carrier status. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2017;5:508–15.

Freed AS, Gruss I, McMullen CK, Leo MC, Kauffman TL, Porter KM, et al. A decision aid for additional findings in genomic sequencing: Development and pilot testing. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104:960–8.

Reumkens K, Tummers MHE, Gietel-Habets JJG, van Kuijk SMJ, Aalfs CM, van Asperen CJ, et al. The development of an online decision aid to support persons having a genetic predisposition to cancer and their partners during reproductive decision-making: a usability and pilot study. Fam Cancer. 2019;18:137–46.

Korngiebel DM, McMullen CK, Amendola LM, Berg JS, Davis JV, Gilmore MJ, et al. Generating a taxonomy for genetic conditions relevant to reproductive planning. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170:565–73.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Rachael, Jonathan and Mackenzie Casella; and the MM program leads Edwin Kirk, Nigel Laing and Martin Delatycki for the conception of the MM program. The initiation and drafting of the RGCS-DA was the responsibility of the MM Education and Engagement Committee and the MM Psychosocial and Epidemiology subcommittee members. We also acknowledge the contribution of the MM Operations team for the development of the study protocol and build of the website which hosts the RGCS-DA. A full list of committee and team members can be found at https://www.mackenziesmission.org.au/our-team/. The authors acknowledge the Delphi experts; and interview participants for their contribution to the final RGCS-DA. We thank Nigel Laing and Lisa Dive who provided critical review of this paper.

Funding

The Australian Reproductive Genetic Carrier Screening Project (Mackenzie’s Mission) is funded by the Australian Government’s Medical Research Future Fund as part of the Australian Genomics Health Futures Mission (GHFM), grant GHFM73390 (MRFF- G-MM). The grant is administered by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute through Australian Genomics. This work was supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EK and JH led the adaptation of the DA and the Delphi review. EK conducted development interviews and modified the DA. BM and AA conducted experience interviews and EK, JH and BM co-coded the interviews. EK drafted the paper and all authors revised drafts and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study has Human Research Ethics Committee approval (The Royal Children’s Hospital, 2019.097_V3).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

King, E., Halliday, J., Archibald, A.D. et al. Development and use of the Australian reproductive genetic carrier screening decision aid. Eur J Hum Genet 30, 194–202 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-00991-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-00991-x

This article is cited by

-

Exploring attitudes and experiences with reproductive genetic carrier screening among couples seeking medically assisted reproduction: a longitudinal survey study

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2024)

-

Genetic Counsellors play a key role in supporting ethically responsible expanded universal carrier screening

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

A new system for variant classification?

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)