Abstract

Germline variants in the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) gene PMS2 cause 1–14% of all Lynch Syndrome cancers. Correct variant analysis of PMS2 is complex due to the presence of multiple pseudogenes and the occurrence of gene conversion. The analysis complexity increases in highly fragmented DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue. Here we describe a reliable approach to detect true PMS2 variants in fragmented DNA. A custom NGS panel designed for FFPE tissue was used targeting four MMR genes, POLE and POLD1. Amplicon design for PMS2 was based on the position of paralogous sequence variants (PSVs) that distinguish PMS2 from its pseudogenes. PMS2 variants in exons 1–11 can be correctly curated based on this information. For exons 12–15 this is less reliable as these undergo gene conversion. Using this method, we screened PMS2 variants in 125 MMR-deficient tumors. Of the 125 tumors tested, six were unexplained MMR-deficient tumors with solitary PMS2 protein expression loss. In these six tumors two unclassified variants (class 3) and five variants likely affecting function (class 4/5) were detected in PMS2. One microsatellite unstable tumor with positive staining for all MMR proteins was found to carry a frameshift PMS2 variant (class 5). No class 4 or class 5 PMS2 variants were detected in tumors with other patterns of MMR protein expression loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heterozygous germline variants in the MMR genes cause Lynch Syndrome (LS), an autosomal dominant predisposition for mainly colorectal- and endometrial cancer [1]. Most of the reported variants up to now are found in the MLH1 and MSH2 gene [2, 3]. However, recent studies show that PMS2 (and MSH6) variants affecting protein function in unselected, population based cohorts are actually much more prevalent [4].

An explanation for this discrepancy is the fact that the colorectal cancer (CRC) risk of PMS2 variant (that affects function) carriers has shown to be much lower compared with MLH1 and MSH2 with risk of CRC around 11–19% by the age of 70 years, and many PMS2 variant (that affects function) carriers remain undetected [5]. The introduction of population based staining for MMR deficiency in colon and endometrial cancers under age 70 in many countries will very likely result in a higher detection of PMS2 variants. Supporting a higher prevalence of PMS2 variants is the fact that homozygous or compound heterozygous variants in the PMS2 gene are seen more often in patients with constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD), a recessive disorder characterized by CRC and childhood hematological- and brain malignancies [6].

The previous underestimation of PMS2 variant (that affects function) carriers may have also been caused by the presence of multiple PMS2 pseudogenes, which hamper the analysis of PMS2 [3, 7, 8]. Fourteen PMS2-pseudogenes share a high homology with the 5' end of PMS2 (exons 1–5), while a fifteenth pseudogene (PMS2CL) shares high homology with PMS2 exon 9 and exon 11–15 [2, 8,9,10,11]. Additional complexity is added through ongoing gene conversion events between PMS2 and PMS2CL [11]. Germline variant screening strategies propose long-range PCR with a reverse primer in PMS2 exon 6 or propose designing multiplex ligation-dependent amplification (MLPA) probes, and PCR primers, based on paralogous sequence variants (PSVs) to distinguish PMS2 exons 1–5 from the fourteen homologous pseudogenes [2, 10, 12]. These PSVs are specific nucleotides that differ between PMS2 and the pseudogenes, and enable differentiation between two almost complete homologues sequences [3, 9, 10]. This strategy is not reliable in detecting variants in exons 12–15 due to gene conversion events between PMS2 and PMS2CL [11, 13]. Through crossover the sequence corresponding to PMS2 or PMS2CL could be present as the exons 12–15 sequence of PMS2, and subsequently expressed [10,11,12]. To determine which sequence is present, and expressed, long-range PCR on genomic DNA (gDNA) or cDNA is proposed using primers in the unique exon 10 and a nonspecific reverse primer in the 3′ UTR [10, 11, 13,14,15].

While this strategy is very suitable for reliable detection of PMS2 variants in leukocyte DNA, it is not applicable when using DNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks, which is highly fragmented [16]. There is a high need for reliable detection of somatic PMS2 variants in DNA isolated from FFPE tissue as it has been recently shown that a large proportion of MMR-deficient tumors without germline MMR variants and without MLH1 promoter hypermethylation can be explained by two somatic MMR variants [17,18,19]. Moreover, testing DNA isolated from FFPE will enable screening of deceased index patients of which only FFPE material is available. Lastly, to implement reliable PMS2 variant screening in molecular tumor diagnostics, a high-throughput strategy should be developed.

Most studies only focus on screening for variants in MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6, possibly because of the complexity of screening for true PMS2 variants [17]. We now describe possible pitfalls in PMS2 variant detection and propose a next generation sequencing (NGS) based approach for reliable testing of PMS2 in FFPE DNA.

Material and methods

Study cohort

Two patient cohorts were included in this study. In the first cohort, 40 patients with LS associated cancer were screened for somatic DNA variants in the MMR genes in a diagnostic setting. Patients presented with colorectal cancer (CRC, n = 23), endometrial or ovarian cancer (EC/OC, n = 12), sebaceous gland cancer (n = 2), breast cancer (n = 2) or colorectal adenomas (n = 1). The average age of onset was 55.8 years (range 31–87), and 26 patients were female. The patients presenting with breast cancer both had a history of CRC or EC. The majority of tumors screened showed loss of expression of one or more mismatch repair (MMR) proteins with immunohistochemical staining (IHC) and/or microsatellite instability (MSI) (n = 35), but five patients with a family history of CRC were also screened, while having a MMR-proficient phenotype. All experiments were performed in the ISO-15189 certified pathology laboratory of the LUMC. For IHC the laboratory routinely participates in NordiQC quality assessment evaluations. All MLH1/PMS2 negative tumors tested negative for MLH1 promoter hypermethylation. Four tumors had solitary immunohistochemical expression loss of PMS2. In a second retrospective research patient cohort, DNA isolated from FFPE tissue blocks of 85 unexplained suspected LS patients (without germline MMR variants and without MLH1 promoter hypermethylation) were screened for variants in the MMR genes in a research setting. Two of the MMR-deficient tumors showed isolated PMS2 expression loss with IHC. Average age of onset of the first Lynch-associated tumor was 51.9 years (range 30–81). IHC and MSI had previously been performed at request of board certified Clinical Genetics medical specialists.

NGS panel

Using the Ion Ampliseq™ tool, two custom NGS panels were designed covering MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, POLE and POLD1. Libraries were prepared with Ion AmpliSeq™ Library Kit 2.0 according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Both panels had comparable coverage, although the diagnostic panel covered 76.5% of PMS2 (exons 1–12), while the research panel covered 79.1% of PMS2 (exons 1–11 and exon 14). Next-generation sequencing data was generated using the Ion Proton™ System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

NGS annotation

The unaligned BAM files, generated by the Proton sequencer, were mapped against the human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) using the TMAP 5.0.7 software with default parameters (https://github.com/iontorrent/TS). A mapping score is calculated for each read, where the read receives a positive score for each base that matches the reference sequence, and a negative score for each mismatch and/or each deletion. A read will receive multiple mapping scores for different genomic locations where it could possibly be mapped. The read is then assigned to the genomic location with the highest mapping score. In case that a particular read gets the same alignment score at multiple locations, it will be randomly assigned to one of the loci. Subsequently, variant calling was done using the Ion Torrent specific caller, Torrent Variant Caller (TVC)-5.0.2.

All identified PMS2 variants (likely) affecting function were visually inspected using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) [20, 21]. The following Genbank reference sequences were used: NM_000249.3 for MLH1, NM_000251.2 for MSH2, NM_000179.2 for MSH6, NM_000535.5 for PMS2, NM_006231.2 for POLE and NM_001256849.1 for POLD1. PMS2 exons are numbered as for transcript ENST00000265849.11. Classification of the functional effects of the variants was done according to the five-tiered InSiGHT scheme [22]. As per Human Genome Variation Society guidelines the term “affects function” was used instead of “pathogenic”. All PMS2 variants were added to the gene variant database at www.LOVD.nl/PMS2 (individual IDs: 00208595–00208632).

Results

Two custom MMR panels were designed for detecting variants in DNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue. As FFPE material is known to result in fragmented DNA, the designed amplicons have sizes ranging from 100 to 175 bp. PMS2 exons 1–11 can be screened due to the PMS2-specific PSVs. To be able to distinguish a NGS-read as PMS2, every amplicon should at least have one PSV. The two panels (diagnostic and research) covered 96 and 94% of exons 1–11, respectively. A complete overview of PSVs and amplicons is shown in the Supplemental Information, while one of the amplicons (exon 9) is shown in Fig. 1.

By exploiting the presence of PSVs in PMS2 plus by mapping reads to the full genome and not only to target regions, 125 MMR-deficient tumors (including six tumors with solitary PMS2 expression loss) were screened for variants in PMS2. Matching normal colonic mucosa was sequenced when available. Five PMS2 variants (likely) affecting protein function (class 4/5) and two variants of uncertain significance (VUS, class 3) were detected in the tumors with solitary loss of PMS2 expression (Table 1). The PMS2 c.(308 C > T/ 308=) (p.(T103I), class 3) and c.1687C > T (p.(R563*), class 5) were found in tumors with a variant in the exonuclease domain of POLE, where the PMS2 variant is expected to be secondary to the POLE variant [23]. All patients previously tested negative for germline variants in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2. In addition, one tumor with positive staining for all MMR proteins and a MSI-H phenotype was found to carry a frameshift PMS2 c.325dupG (p.(E109fs)) variant (Table 1). Interestingly, this patient was previously only tested for germline variants in MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6, but sequencing of leukocyte DNA after detection of the PMS2 c.325dupG variant detected in the tumor showed that this variant was also present in the germline. In remaining cases with MLH1/PMS2, MSH2/MSH6 or solitary MSH6 expression loss, no PMS2 variant likely affecting function was detected.

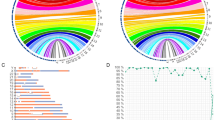

Even though PMS2 primers amplified more than one locus, due to the presence of PSVs in PMS2 exons 1–11, the amplified loci are not completely homologous. By aligning the reads to the full genome and by assigning them to the locus with the higher mapping score, variants could be properly called. In addition, IGV was used to visually inspect that reads were mapped to the right locus (Fig. 2). This was performed for all eight PMS2 variants shown in Table 1, and all variants were found to be present in PMS2 and not one of the pseudogenes.

PMS2 variants detected with NGS. IGV printout of the PMS2 c.955 C > A, p.(P319T) shown (left) and the corresponding reads aligned to the PMS2CL gene (variant absent). Arrows show the location of three PSVs present in the amplicon (1. c.934 A > G, 2. c.932 A > G and 3. c.924 G > C). All three are absent in the PMS2 reads, while present in the PMS2CL reads. PMS2 is shown in reverse complement, because PMS2 is translated on the reverse strand

Discussion

Using targeted NGS, we now describe how to reliably call PMS2 variants present in DNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue and how to mitigate the presence of pseudogenes by using PSVs. Six out of eight PMS2 variants detected were located in exons with high homology with one or more of the PMS2 pseudogenes. By exploring the presence of PSVs in the amplicon and aligning the reads to the complete genome, and not only the target regions, it could be concluded that all variants were truly present in PMS2 and not in the pseudogenes. This approach was additionally used in a recent study investigating somatic variants in 20 tumors of PMS2-associated LS patients [24]. In this study, the second somatic hit was identified in 16 out of 20 analysed tumors (in nine tumors loss of heterozygosity and in eight tumors a somatic class 4 or class 5 variant) [24].

Although a reliable distinction between PMS2 and its pseudogenes could be made for PMS2 exons 1–11, exons 12–15 variants cannot be reliably detected due to the existence of continuous gene conversion targeting these exons. A solution to this challenge is long range PCR of fragments covering PMS2 exons 12–15 [10, 11]. However, because of the fragmented nature of the DNA this is not possible in FFPE tissue.

Studies that aim to detect PMS2 variants in DNA from FFPE tissues are very limited. Only six studies describe somatic analysis of PMS2 [18, 19, 23,24,25,26]. We and others achieve a total PMS2 coverage of 75–80% (100% of PMS2 exons 1–11) and do not sequence PMS2 exons 12–15 completely. Haraldsdottir et al. did claim full coverage of PMS2 in tumor tissue [26]. However, they did not fully explain how they coped with gene conversion of exons 12–15 [26]. For example, one PMS2 splice site variant in intron 12 was shown without confirmation of its presence in PMS2 and not in PMS2CL through gene conversion, while gene conversion is a frequent event (previously shown to occur in 69% of tested individuals) [11]. This example typically highlights the existing problem with sequencing of PMS2 exons 12–15. Consensus should be reached whether PMS2 exons 12–15 should be sequenced in FFPE-tissue, when it cannot be confirmed that these variants are truly present in PMS2 (and subsequently expressed). Although the current study included PMS2 exons 12 and 14 in our research panel, caution is needed when analysing these variants. However, it could be considered that a PMS2 exons 12–15 variant likely affecting protein function detected in a tumor with solitary PMS2 loss of expression with no other PMS2 variants, is likely present in PMS2 (and not PMS2CL), and is the cause of the immunohistochemical loss of PMS2 expression. In addition, since expressed genes have elevated mutation rates, if a somatic variant is detected in PMS2 exons 12–15 it is likely that PMS2 is expressed [27]. However, only RNA sequencing can confirm whether a variant is expressed.

In conclusion, with a custom NGS panel and by using the presence of PSVs, we were able to reliably detect eight somatic variants in PMS2 exons 1–11 in six tumors. Previous studies describe comprehensive strategies for accurate variant detection in PMS2, but mainly focus on testing genomic DNA extracted from blood [10, 28]. Since recent studies have shown biallelic somatic inactivation of the MMR genes, there is a growing need for accurate detection of somatic variants in PMS2 [17,18,19, 23]. With this guide we show a reliable method to detect PMS2 variants in DNA from FFPE tissue for exons 1–11 (73–74% of the gene).

References

Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:919–32.

Borras E, Pineda M, Cadinanos J, Del Valle J, Brieger A, Hinrichsen I, et al. Refining the role of PMS2 in Lynch syndrome: germline mutational analysis improved by comprehensive assessment of variants. J Med Genet. 2013;50:552–63.

Hendriks YM, Jagmohan-Changur S, van der Klift HM, Morreau H, van Puijenbroek M, Tops C, et al. Heterozygous mutations in PMS2 cause hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (Lynch syndrome). Gastroenterology. 2006;130:312–22.

Win AK, Jenkins MA, Dowty JG, Antoniou AC, Lee A, Giles GG, et al. Prevalence and penetrance of major genes and polygenes for colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26:404–12.

ten Broeke SW, Brohet RM, Tops CM, van der Klift HM, Velthuizen ME, Bernstein I, et al. Lynch syndrome caused by germline PMS2 mutations: delineating the cancer risk. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:319–25.

Vasen HF, Ghorbanoghli Z, Bourdeaut F, Cabaret O, Caron O, Duval A, et al. Guidelines for surveillance of individuals with constitutional mismatch repair-deficiency proposed by the European Consortium “Care for CMMR-D” (C4CMMR-D). J Med Genet. 2014;51:283–93.

Kondo E, Horii A, Fukushige S. The human PMS2L proteins do not interact with hMLH1, a major DNA mismatch repair protein. J Biochem. 1999;125:818–25.

Nicolaides NC, Carter KC, Shell BK, Papadopoulos N, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Genomic organization of the human PMS2 gene family. Genomics. 1995;30:195–206.

De Vos M, Hayward BE, Picton S, Sheridan E, Bonthron DT. Novel PMS2 pseudogenes can conceal recessive mutations causing a distinctive childhood cancer syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:954–64.

van der Klift HM, Mensenkamp AR, Drost M, Bik EC, Vos YJ, Gille HJ, et al. Comprehensive mutation analysis of PMS2 in a large cohort of probands suspected of lynch syndrome or constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:1162–79.

van der Klift HM, Tops CM, Bik EC, Boogaard MW, Borgstein AM, Hansson KB, et al. Quantification of sequence exchange events between PMS2 and PMS2CL provides a basis for improved mutation scanning of Lynch syndrome patients. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:578–87.

Wernstedt A, Valtorta E, Armelao F, Togni R, Girlando S, Baudis M, et al. Improved multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification analysis identifies a deleterious PMS2 allele generated by recombination with crossover between PMS2 and PMS2CL. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:819–31.

Hayward BE, De Vos M, Valleley EM, Charlton RS, Taylor GR, Sheridan E, et al. Extensive gene conversion at the PMS2 DNA mismatch repair locus. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:424–30.

Clendenning M, Walsh MD, Gelpi JB, Thibodeau SN, Lindor N, Potter JD, et al. Detection of large scale 3’ deletions in the PMS2 gene amongst Colon-CFR participants: have we been missing anything? Fam Cancer. 2013;12:563–6.

Etzler J, Peyrl A, Zatkova A, Schildhaus HU, Ficek A, Merkelbach-Bruse S, et al. RNA-based mutation analysis identifies an unusual MSH6 splicing defect and circumvents PMS2 pseudogene interference. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:299–305.

Daugaard I, Kjeldsen TE, Hager H, Hansen LL, Wojdacz TK. The influence of DNA degradation in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue on locus-specific methylation assessment by MS-HRM. Exp Mol Pathol. 2015;99:632–40.

Mensenkamp AR, Vogelaar IP, van Zelst-Stams WA, Goossens M, Ouchene H, Hendriks-Cornelissen SJ, et al. Somatic mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 are a frequent cause of mismatch-repair deficiency in Lynch syndrome-like tumors. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:643–6.e8.

Geurts-Giele WR, Leenen CH, Dubbink HJ, Meijssen IC, Post E, Sleddens HF, et al. Somatic aberrations of mismatch repair genes as a cause of microsatellite-unstable cancers. J Pathol. 2014;234:548–59.

Jansen AM, Geilenkirchen MA, van Wezel T, Jagmohan-Changur SC, Ruano D, van der Klift HM, et al. Whole gene capture analysis of 15 CRC susceptibility genes in suspected lynch syndrome patients. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0157381.

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotech. 2011;29:24–6.

Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:178–92.

Thompson BA, Spurdle AB, Plazzer JP, Greenblatt MS, Akagi K, Al-Mulla F, et al. Application of a 5-tiered scheme for standardized classification of 2,360 unique mismatch repair gene variants in the InSiGHT locus-specific database. Nat Genet. 2014;46:107–15.

Jansen AM, van Wezel T, van den Akker BE, Ventayol Garcia M, Ruano D, Tops CM, et al. Combined mismatch repair and POLE/POLD1 defects explain unresolved suspected Lynch syndrome cancers. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1089–92.

Ten Broeke SW, van Bavel TC, Jansen AML, Gomez-Garcia E, Hes FJ, van Hest LP, et al. Molecular background of colorectal tumors from patients with lynch syndrome associated with germline variants in PMS2. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:844–51.

Stelloo E, Jansen AM, Osse EM, Nout RA, Creutzberg CL, Ruano D, et al. Practical guidance for mismatch repair-deficiency testing in endometrial cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:96–102.

Haraldsdottir S, Hampel H, Tomsic J, Frankel WL, Pearlman R, de la Chapelle A, et al. Colon and endometrial cancers with mismatch repair deficiency can arise from somatic, rather than germline, mutations. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1308–16 e1.

Zhang J, Yang J-R. Determinants of the rate of protein sequence evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:409–20.

Li J, Dai H, Feng Y, Tang J, Chen S, Tian X, et al. A comprehensive strategy for accurate mutation detection of the highly homologous PMS2. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17:545–53.

Senter L, Clendenning M, Sotamaa K, Hampel H, Green J, Potter JD, et al. The clinical phenotype of Lynch syndrome due to germ-line PMS2 mutations. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:419–28.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society under study number UL2012–5542.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMLJ: Acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript, CMJT; interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript, DR: technical support, critical revision of the manuscript, RvE; technical support, critical revision of the manuscript. JW: Obtained funding, critical revision manuscript. StB, MN: Critical revision of the manuscript, FJH, TvW, HM: study concept and design, obtained funding, critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jansen, A.M.L., Tops, C.M.J., Ruano, D. et al. The complexity of screening PMS2 in DNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded material. Eur J Hum Genet 28, 333–338 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0527-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0527-x

This article is cited by

-

Performance evaluation of pipelines for mapping, variant calling and interval padding, for the analysis of NGS germline panels

BMC Bioinformatics (2021)

-

Application of targeted nanopore sequencing for the screening and determination of structural variants in patients with Lynch syndrome

Journal of Human Genetics (2021)

-

Primary mismatch repair deficient IDH-mutant astrocytoma (PMMRDIA) is a distinct type with a poor prognosis

Acta Neuropathologica (2021)