Abstract

Background

Higher maternal preconception body mass index (BMI) is associated with lower breastfeeding duration, which may contribute to the development of poor child eating behaviours and dietary intake patterns (components of nutritional risk). A higher maternal preconception BMI has been found to be associated with higher child nutritional risk. This study aimed to determine whether breastfeeding duration mediated the association between maternal preconception BMI and child nutritional risk.

Methods

In this longitudinal cohort study, children ages 18 months to 5 years were recruited from The Applied Research Group for Kids (TARGet Kids!) in Canada. The primary outcome was child nutritional risk, using The NutriSTEP®, a validated, parent-reported questionnaire. Statistical mediation analysis was performed to assess whether total duration of any breastfeeding mediated the association between maternal preconception BMI and child nutritional risk.

Results

This study included 4733 children with 8611 NutriSTEP® observations. The mean (SD) maternal preconception BMI was 23.6 (4.4) and the mean (SD) breastfeeding duration was 12.4 (8.0) months. Each 1-unit higher maternal preconception BMI was associated with a 0.081 unit higher nutritional risk (95% CI (0.051, 0.112); p < 0.001) (total effect), where 0.011(95% CI (0.006, 0.016); p < 0.001) of that total effect or 13.18% (95% CI: 7.13, 21.25) was mediated through breastfeeding duration.

Conclusion

Total breastfeeding duration showed to mediate part of the association between maternal preconception BMI and child nutritional risk. Interventions to support breastfeeding in those with higher maternal preconception BMI should be evaluated for their potential effect in reducing nutritional risk in young children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal body mass index (BMI) in the preconception period has been shown to be an important determinant of breastfeeding success. Higher preconception BMI has been associated with lower breastfeeding initiation rates and shorter duration of both exclusive breastfeeding and any breastfeeding [1,2,3,4]. Mothers with lower income, a key factor found to be associated with obesity [5], are similarly less likely to breastfeed for longer durations [6, 7].

Children who are breastfed longer are more likely to develop optimal healthy eating patterns and behaviours in early childhood [8,9,10,11], with research suggesting the greatest benefit when a child is breastfed up to 12 months or longer [12,13,14,15]. Poor nutrition in early childhood is itself a risk factor for obesity in later childhood and the development of non-communicable diseases such as type 2 diabetes [16, 17]. Healthy eating behaviours developed early in life have been shown to persist into adulthood, highlighting the importance of identifying nutritional risk and protective factors in young children [16, 18].

Higher maternal BMI, independent of the preconception period, has been found to be associated with eating behaviours and child dietary intake patterns low in fruits and vegetables [19, 20], while lower maternal BMI has shown to be associated with child dietary patterns higher in fruits, vegetables and other healthy foods [21]. Research examining maternal BMI specifically during the preconception period has similarly found higher BMI to be associated with poor child dietary patterns high in sugary foods and sweetened beverages [22].

Recent research from our group found that higher maternal preconception BMI was associated with higher nutritional risk in young children [23]. However, the mechanisms for this association are poorly understood, leaving gaps in knowledge on how to best support women with higher preconception BMIs with optimising their child’s nutritional health. Breastfeeding duration may be a mediator on the causal pathway between maternal preconception BMI and child nutritional risk, in which case supportive breastfeeding programs designed specifically for women with increased preconception BMI could be a promising strategy for improving child nutritional outcomes.

The primary objective of this study was to determine if total duration of any breastfeeding mediates the association between maternal preconception BMI and nutritional risk in children 18 months to 5 years of age. Secondary objectives included determining if total breastfeeding duration mediates the association between preconception maternal BMI and child eating behaviours and dietary intake patterns, and whether each of these associations varies by household income. It was hypothesised that total duration of any breastfeeding is a mediator of the association between maternal preconception BMI and child nutritional risk, eating behaviours and dietary intake, where mothers with lower household income may experience different mediating effects compared to higher income groups.

Subjects and methods

Study design and participants

This study included children enroled in the TARGet Kids! practice-based research network in Canada. TARGet Kids! recruits children up to 5 years of age and collects longitudinal data at primary care visits [24]. Children were excluded at enrolment who have health conditions affecting growth, chronic condition(s) (excluding asthma), and severe developmental delay. Questionnaires were offered to parents to collect data on sociodemographics, health history, and child nutritional risk. Child and parent anthropometrics were also obtained, including weight, and length, or height, as appropriate by age, using standard practices [25].

This study included children from the TARGet Kids! cohort that were between the ages of 18 months to 5 years, who had completed at least one NutriSTEP® questionnaire and whose mother had a measured or self-reported preconception BMI. The Research Ethics Boards at the Hospital for Sick Children and St. Michaels Hospital both approved this study. Parents of the children eligible and participating in the study provided consent prior to participating. This study can be found online at clinicaltrials.gov registered under NCT01869530.

Exposure

The primary exposure was maternal preconception BMI, defined as any BMI value (BMI = weight(kg)/height2(m2)) recorded within the 2 years prior to becoming pregnant, either measured in clinic or self-reported. Measured weight was obtained when the mother came to a clinic visit with an older sibling already enroled in TARGet Kids!, prior to becoming pregnant with the child in this study analysis (ensured to be measured at 37 weeks or more prior to the second child’s birth date). If a mother did not have her weight measured during preconception, a retrospective self-reported weight was obtained from the study questionnaire. A mother could have had her height measured in clinic each time they accompanied their child to a clinic visit; therefore, the median height of all measures was used in the BMI calculation.

Outcomes

Study outcomes were derived from the NutriSTEP® questionnaire, a parent-reported and validated tool used to measure nutritional risk in children ages 18 months to 5 years, with age specific versions for toddlers (18 to <36 months) and preschoolers (3–5 years) [26, 27]. The primary outcome was nutritional risk, determined from the total NutriSTEP® score, composed of 17 questions on the child’s usual dietary intake, screen time, physical activity, specific eating behaviours, and parent perceptions of growth [26, 27]. The total score ranges from 0 to 68, where a score < 21 is considered low nutritional risk, 21–25 is moderate nutritional risk, and ≥25 is high nutritional risk [26]. For simplicity, study baseline characteristics dichotomised the NutriSTEP® score, resulting in a low-risk (<21) and high-risk score (≥21).

Two sub-scale scores from the questionnaires have been used to study the nutritional risk domains of child eating behaviours and dietary intake [13, 28]. The eating behaviour sub-scale score was comprised of five questions for a score of 0–20 for preschoolers and seven questions for a score of 0–28 for toddlers. The dietary intake sub-scale score was made up of six questions for a score of 0–24 for both toddler and preschooler versions. All analyses with the sub-scale scores were stratified by toddler and preschooler age groups, to understand differences among these two age ranges.

Mediator

The mediator was total breastfeeding duration, defined as total duration in months of the provision of any breast milk, and was self-reported as a categorical variable: 0 months, 0 to <6 months, 6 to <12 months, 12 to <18 months, and ≥18 months. These categories were selected a priori, and were consistent with previous work by our team and others [13]. A categorical variable was used to account for right-censoring beyond 18 months, as a child could still be receiving breast milk when the NutriSTEP® was measured. To our knowledge, methods for censored continuous time-to-event variables as mediators do not currently exist; however, it is possible to include these variables in a mediation model by transforming the mediator into a categorical variable [29, 30]. Total duration of any breastfeeding was chosen, rather than rates of breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity or discontinuation in order to be consistent with previous literature which has shown that total breastfeeding duration is associated with multiple outcomes in child nutrition [12, 13, 15], and studies that evaluated the effect of both exclusive and total breastfeeding, found similar results for each [14].

Covariates

The confounders were determined a priori based on previous literature to align with the specific confounding assumptions for mediation analyses [29]. Confounders included in the model were child age [18], self-reported annual household income (CAD$) [5, 31], maternal age [32, 33], maternal ethnicity [34, 35], and parity [36, 37]. Maternal age was recorded as the age when the preconception BMI was measured, or self-reported. Child age was recorded in months at the time when NutriSTEP® was completed. Based on previous literature examining income, maternal BMI and breastfeeding duration, we decided a prior to stratify the model by household income <$80 000 and ≥$80 000, using the median total household income for the Greater Toronto Area, in Canada [38].

Statistics

Descriptive statistics for the model exposure, outcomes, mediator, and covariates, with additional sociodemographic variables of both the mothers and children were completed. Means with standard deviations or proportions with percentages of each variable were reported for the whole sample and then stratified by maternal preconception BMI < 25 kg/m2 and ≥25 kg/m2. Data cleaning involved removing any BMI outliers according to a previously published protocol used for adult anthropometrics [39]. Any NutriSTEP® questionnaires that were completed when the child was outside of the age range for which the questionnaire had been validated for were also removed from the sample [26, 27]. All model covariates had <15% missingness. Multiple imputations were completed with 15 imputed data sets using the mice package in R to impute missing values of covariates assuming they were missing at random (MAR), or missing completely at random (MCAR) [40]. Under the MAR assumption, we assume a child with a higher or lower NutriSTEP score was not more or less likely to have a NutriSTEP® completed, conditional on the other covariates and variables in the imputation model.

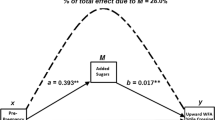

To estimate the mediation effect of different breastfeeding duration categories on the association between maternal preconception BMI and child nutritional risk, the total effect, direct effect, indirect effect, and proportion mediated were calculated with 95% confidence intervals [29, 30], conceptual model shown in Fig. 1. The total effect represents the complete effect that the exposure has on each of the outcomes [30]. The direct effect, represents the effect on the outcome that is not due to the mediator, and can often include intermediates that are not measured in the analysis [30]. The indirect effect or otherwise known as the mediation effect, is the effect on the outcome due to the exposure, via the mediator [30]. Proportion mediated was calculated by dividing the indirect effect by the total effect, where non parametric bootstrap methods were used to bootstrap the model 100 times per imputed dataset, for a total of 1500 bootstrap samples, to obtain the 95% confidence intervals for the proportion mediated values [30]. Within each of the 100 bootstrap samples, Rubin’s rules were used to pool the 15 proportion mediated estimates [41].

This mediation analysis used methods described by Steen et al. through the R package medflex [42]. To account for the chance that an exposure-mediator interaction may be present, models were fit and compared, with and without an interaction term between breastfeeding duration and maternal preconception BMI, with results compared at each maternal preconception BMI quantile of 25%, 50%, and 75%. The mediation analyses were fit for each of the outcomes: total nutritional risk score, eating behaviour sub-scale score and dietary intake sub-scale score, where the two sub-scale scores were stratified by age according to each version of the NutriSTEP® (toddlers 18 to <36 months and preschoolers 36 to <72 months) to account for potentially differing associations in each NutriSTEP® score. Lack of independence between NutriSTEP® observations on the same child was accounted for using robust “sandwich” estimates of the variances [43]. A separate multinomial model was also fit to examine the association between maternal preconception BMI and each breastfeeding duration category.

A secondary analysis was completed where all models were stratified by household income <$80,000 and ≥$80,000, as decided a priori, to account for potential effect modification. Residual plots were assessed to ensure that all model assumptions for linearity, and normality of residuals, and influential observations were met. All p-values that were < 0.05, along with 95% confidence intervals were used to determine statistically significant results. All statistical analyses were completed in R for Mac, version 4.1.1 [44].

Results

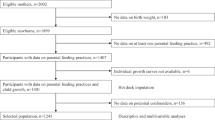

This study included 4733 children, coming from 4440 families, with 1–3 kids per family, with 8611 NutriSTEP® observations. Overall, the children had a mean (SD) age of 35.3 (14.5) months and 51.7% were male sex. The mean (SD) maternal preconception BMI was 23.6 (4.4) and using the WHO BMI classifications indicated that 3.9% of the sample had an underweight BMI, 69.2% had normal weight, 19.1% had overweight, and 7.8% had obesity [45]. The mean (SD) NutriSTEP® total score at baseline, for both toddlers and preschoolers combined was 13.8 (6.4) (n = 4733), with 12.5 (6.0) (n = 2017) for toddlers, and 14.8 (6.6) (n = 2716) for preschoolers. The mean (SD) duration of any breastfeeding was 12.4 (8.0) months, where those with a preconception BMI < 25 kg/m2 (n = 3460) had a mean (SD) duration of 12.6 (7.7) months, and those with a preconception BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (n = 1273) had a mean (SD) duration of 12.0 (8.80) months (Table 1).

When testing for an exposure-mediator interaction between maternal preconception BMI and breastfeeding duration, the total natural direct and pure direct effects, and the total natural indirect and pure indirect effects had similar values with very slight deviations from each other (Supplementary Table 5). This provided sufficient evidence to remove the interaction term in all subsequent models [30].

The multinomial model examining the relationship between maternal preconception BMI and breastfeeding duration category is displayed in Fig. 2. From a multinomial model, there was strong evidence that maternal preconception BMI was associated with breastfeeding duration category (p < 0.001), after adjusting for age, family income, number of siblings, maternal age, and maternal ethnicity, where individual odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are included as a supplement (Supplementary Table 6). Overall, the probabilities for the longer breastfeeding duration categories (>6 months) showed that higher preconception BMI was associated with shorter total breastfeeding duration.

The primary mediation analysis showed that each 1-unit higher maternal preconception BMI was associated with a 0.081 (95% CI (0.051, 0.112); p < 0.001) unit (total effect) higher nutritional risk, where 0.011 (95% CI (0.006, 0.016); p < 0.001) (mediation effect) of that total effect was mediated through breastfeeding duration (Table 2). This translates to the proportion mediated through breastfeeding duration being ~13.18% (95% CI (7.13, 21.25)) in both toddlers and preschoolers combined. When results were stratified by age, for preschoolers, each 1-unit higher maternal preconception BMI was associated with a 0.10 (95% CI (0.06, 0.14); p < 0.001) unit higher nutritional risk, where 0.010 (95% CI (0.004, 0.016); p < 0.001) of that total effect was mediated through breastfeeding duration, with a proportion mediated of 10.06% (95% CI (5.72, 20.09)). For toddlers, while there was evidence of a total effect (0.049; 95% CI (0.003, 0.095; p = 0.035)), there was insufficient evidence for a natural direct effect (p = 0.081), or indirect effect (p = 0.051), and therefore we are unable to conclude if there is a mediation effect in this sub-group.

For the preschoolers, each 1-unit higher maternal preconception BMI was associated with a 0.032 (95% CI (0.018, 0.045); p < 0.001) unit higher in eating behaviour sub-scale score, where 0.004 (95% CI (0.002, 0.006); p < 0.001) of that total effect was mediated through breastfeeding duration, with a proportion mediated of 11.88% (95% CI (7.08, 24.06)). For the dietary intake sub-scale score in preschoolers, each 1-unit higher maternal preconception BMI was associated with a 0.050 (95% CI (0.029, 0.071); p < 0.001) unit higher dietary intake sub-scale score, where 0.005 (95% CI (0.002, 0.007); p < 0.001) was mediated through breastfeeding duration, with a proportion mediated of 9.23% (95%CI (4.66, 15.95)) (Table 3). There was insufficient evidence to conclude if there was a mediation effect for the eating behaviour sub-scale score in toddlers as seen with the p-values for the total effect (p = 0.087) and direct effect (p = 0.224). There was insufficient evidence to conclude a mediation effect for the dietary intake sub-scale score in the toddler age group, where the p-values were >0.05 for the indirect effect (p = 0.195), direct effect (p = 0.152), and total effect (p = 0.098).

When the mediation results were stratified by household income, 892 children fell into the lower income group (<$80,000), while 3176 children fell into the higher income group (≥$80,000). For the higher income group, each 1-unit higher maternal preconception BMI was associated with a 0.124 (95% CI (0.090, 0.159); p < 0.001) unit higher in NutriSTEP® total score, where 0.012 (95% CI (0.060, 0.018); p < 0.001) was mediated through breastfeeding duration, with a proportion mediated of 9.68% (Table 4). There was no evidence that these associations were present in the lower income group, where the total effect was estimated to be 0.032 (95% CI (−0.033, 0.096); p = 0.336) with a mediation effect of 0.007 (95% CI (−0.004, 0.017); p = 0.217). When these results were further stratified by toddler and preschooler age groups, significant findings were found in the higher income group only (Supplementary Table 7).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine breastfeeding duration as a mediator between preconception maternal BMI and early child nutritional risk. We found total duration of any breastfeeding mediated ~13.18% of the association between maternal preconception BMI with nutritional risk in toddler and preschooler-aged children. When these results were stratified by age group, the mediation effect showed statistical significance in the preschooler age group only, with a proportion mediated of 10.06%. In the preschoolers, evidence of a mediation effect was found where breastfeeding accounted for ~11.88% of the association with eating behaviours and 9.23% of the association with dietary intake. Previous findings from our research team found that a higher maternal preconception BMI was associated with a higher child nutritional risk [23], while one other study found a higher preconception maternal BMI to be a predictor of poor dietary intake patterns in toddlers [22]. These findings are important clinically because providing breastfeeding support for women with higher preconception BMIs is a potential preventive opportunity to improve early child nutritional outcomes. Additionally, since total breastfeeding duration only partly mediated the overall effect, it suggests that there may be other potentially modifiable targets between preconception and early childhood which may help optimise child nutritional health. These targets may be similar to mechanisms seen in the association between preconception BMI and child BMI such as metabolic programming via epigenetic mechanisms. Further study is required to investigate other potential mechanisms.

Maternal preconception obesity may be associated with breastfeeding duration through barriers in infant latching [46], disruption in lactogenesis II [47], and lower milk production in mothers with obesity [48]. Maternal obesity is also associated with increased risk for postpartum depression and lower levels of breastfeeding self-efficacy, both known risk factors for decreased breastfeeding duration [49, 50]. Unfortunately, those living with overweight and obesity have been found to experience weight stigma from lactation experts, which in turn decreases the mothers’ desire to seek help in navigating these breastfeeding barriers [51].

Breastfeeding is thought to help children develop eating behaviours that are protective against obesity through the development of satiety cue regulation [52]. Variations in the hormones and human milk components found in breast milk can also vary across mothers by BMI, specifically leptin and insulin, which can influence child hunger, satiety and growth patterns [53]. Rogers et al. found a longer breastfeeding duration was associated with children eating slower, a behaviour thought to be protective against obesity in later life [12]. Yelverton et al., found in their cross-sectional cohort study that longer total breastfeeding duration was associated with lower food responsiveness (general appetite for food or desire to eat) at 5 years of age, another obesogenic protective behaviour [54]. Longer breastfeeding duration was also found to be associated with maternal feeding behaviours where mothers were less likely to restrict children’s food intake at 1 year of age, which can help promote better child self-regulation around food [55].

Many studies have investigated breastfeeding duration, both exclusive and total duration, and their associations with child dietary intake. Perrine et al. found that longer exclusive and total breastfeeding durations to be associated with overall higher odds of consuming daily intakes of fruits, vegetables and lower odds of sugar-sweetened beverages and juice at 6 years of age [14]. Burnier et al., found that children who were exclusively breastfed for longer than 3 months had higher odds of consuming more daily servings of vegetables at 4 years of age [10]. Soldateli et al., found breastfeeding duration in adolescent mothers for 12 months or longer, but not exclusive breastfeeding, was associated with increased weekly vegetable consumption in children at 4–7 year of age [15]. Our research team found that breastfeeding durations of >6–12 months was associated with a lower child nutritional risk and decreased sugary and sweet snack consumption at 3–5 years of age [13].

We found insufficient evidence to conclude a mediating effect of breastfeeding in those who reported earning an annual household income below $80,000. There is evidence that in high-income countries, women living with lower income have increased obesity rates [5], and shorter breastfeeding durations [56]. While research has found that maternal preconception BMI is associated with nutritional risk outcomes in early childhood [22], it is unknown if this association is stronger in higher-income families. There are conflicting results in toddlers with lower household income, where toddlers with lower household income was associated with poorer diet quality compared to those with higher incomes [22]. Another study, found no evidence of an association between household income and vegetable intake in children at 4 years of age [10].

One possible reason for why we were unable to find evidence of a mediation effect in lower-income families may be a ceiling effect. NutriSTEP® scores were on average higher in the low-income group, with larger proportion in the moderate to high-risk category (Supplementary Table 8). It is possible that the NutriSTEP® is more sensitive to changes lower in its score range. If that is the case, we would expect factors associated with the total NutriSTEP® (such as breastfeeding and/or maternal preconception BMI) to have stronger associations in the lower range of the NutriSTEP®; therefore, populations that tend to have lower NutriSTEP® scores, such as the higher income group in this study, may see stronger associations with the NutriSTEP® score. This may explain why the total effect in the higher income group was much higher than in the lower income group, and the estimated proportion mediated was higher in the lower income group. We also found that compared to those with higher income, those with lower income had less variation in breastfeeding duration by BMI, suggesting that the relationship between BMI and breastfeeding duration is not as strong in lower income population in our study (Supplementary Fig. 3). It is also possible that our study may not have been sufficiency powered to detect a mediation effect in this lower income group (n = 892 lower income, n = 3176 higher income). Future work should investigate these relationships in lower income populations.

Strengths of this study include a large sample size of mothers and children, with data on breastfeeding and child nutritional risk. The study analysis also included adjustment for covariates shown in previous literature to potentially confound these relationships. The mediator, total breastfeeding duration, had very little missingness (<1%). The study outcome, measured by NutriSTEP® provided an overall assessment of potential nutritional factors that may contribute to a child’s overall nutritional status, rather than a singular measure of dietary intake often reported in other similar studies.

The study had a lower proportion earning below an annual household income of $80,000, which may have limited power to detect mediation differences in this group. Maternal diet, gestational weight gain, and maternal health factors during preconception could be a source of unmeasured confounding, and prospective data collection for these factors are ongoing. Education attainment is a factor associated with obesity and poor breastfeeding outcomes [57, 58], where our sample had low variation in maternal education, therefore we were unable to adjust for this potential effect in the analysis. This study utilised more self-reported preconception BMIs than measured values, where it has been shown that self-reported preconception weight is often subject to under report, it has also been shown that self-reported BMI from pre-pregnancy are reportedly accurate, and misclassification and magnitudes of error are often small [59]. We did not obtain information on whether the lactating person identified as female, and therefore acknowledge the term breastfeeding may not be inclusive for all. Mean (SD) duration of breastfeeding was not clinically different between those with obesity and overweight (12.6 (7.7)) and those with underweight and normal weight (12.0 (8.80)). Lastly, this study did not examine breastfeeding exclusivity. However, research has indicated that both exclusive and total duration breastfeeding measures are highly correlated, where exclusive breastfeeding for 4–17 weeks was found to be associated with total breastfeeding duration at 15 different timepoints in the first year of life [60].

This study found that total breastfeeding duration mediated ~13% of the association between higher maternal preconception BMI with a higher nutritional risk in children ages 18 months to 5 years. Dietary intake preferences and eating behaviours are developed early and track into adulthood. This study supports that higher maternal preconception BMI may negatively impact total breastfeeding duration, which may contribute to nutritional risk in childhood. This study was unable to conclude a mediation effect in the lower income group, and future studies are needed to determine which factors that are unique to low-income families. Future research could include the role of paternal BMI, along with other paternal health and lifestyle factors during preconception and how it may relate to outcomes in child nutritional health. These findings highlight that the preconception period may be an important time in life to develop and test preventative interventions to optimise maternal health for improving breastfeeding duration and children’s nutritional health.

Data availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval.

References

Flores TR, Mielke GI, Wendt A, Nunes BP, Bertoldi AD. Prepregnancy weight excess and cessation of exclusive breastfeeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:480–8.

Hashemi-Nazari SS, Hasani J, Izadi N, Najafi F, Rahmani J, Naseri P, et al. The effect of pre-pregnancy body mass index on breastfeeding initiation, intention and duration: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2020;6:e05622.

Wojcicki JM. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. J Women’s Health. 2011;20:341–7.

Huang Y, Ouyang YQ, Redding SR. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and cessation of breastfeeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breastfeed Med J Acad Breastfeed Med. 2019;14:366–74.

Kim TJ, von dem Knesebeck O. Income and obesity: what is the direction of the relationship? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019862.

Ryan AS, Zhou W. Lower breastfeeding rates persist among the special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children participants, 1978–2003. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1136–46.

Temple Newhook J, Newhook LA, Midodzi WK, Murphy Goodridge J, Burrage L, Gill N, et al. Poverty and breastfeeding: comparing determinants of early breastfeeding cessation incidence in socioeconomically marginalized and privileged populations in the FiNaL study. Health Equity. 2017;1:96–102.

De Cosmi V, Scaglioni S, Agostoni C. Early taste experiences and later food choices. Nutrients. 2017;9:E107.

Scaglioni S, De Cosmi V, Ciappolino V, Parazzini F, Brambilla P, Agostoni C. Factors influencing children’s eating behaviours. Nutrients. 2018;10:E706.

Burnier D, Dubois L, Girard M. Exclusive breastfeeding duration and later intake of vegetables in preschool children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:196–202.

Ventura AK. Does breastfeeding shape food preferences? links to obesity. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;70:8–15.

Rogers SL, Blissett J. Breastfeeding duration and its relation to weight gain, eating behaviours and positive maternal feeding practices in infancy. Appetite. 2017;108:399–406.

Borkhoff CM, Dai DWH, Jairam JA, Wong PD, Cox KA, Maguire JL, et al. Breastfeeding to 12 mo and beyond: nutrition outcomes at 3 to 5 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108:354–62.

Perrine CG, Galuska DA, Thompson FE, Scanlon KS. Breastfeeding duration is associated with child diet at 6 years. Pediatrics. 2014;134:S50–55.

Soldateli B, Vigo A, Giugliani ERJ. Effect of pattern and duration of breastfeeding on the consumption of fruits and vegetables among preschool children. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0148357.

Craigie AM, Lake AA, Kelly SA, Adamson AJ, Mathers JC. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2011;70:266–84.

Kim J, Lim H. Nutritional management in childhood obesity. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019;28:225–35.

Birch L, Savage JS, Ventura A. Influences on the development of children’s eating behaviours: from infancy to adolescence. Can J Diet Pr Res. 2007;68:s1–56.

Haycraft E, Karasouli E, Meyer C. Maternal feeding practices and children’s eating behaviours: a comparison of mothers with healthy weight versus overweight/obesity. Appetite. 2017;116:395–400.

Andersen LBB, Pipper CB, Trolle E, Bro R, Larnkjær A, Carlsen EM, et al. Maternal obesity and offspring dietary patterns at 9 months of age. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:668–75.

Fisk CM, Crozier SR, Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Cooper C, Robinson SM, et al. Influences on the quality of young children’s diets: the importance of maternal food choices. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:287–96.

Kiefte-de Jong JC, de Vries JH, Bleeker SE, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Raat H, et al. Socio-demographic and lifestyle determinants of ‘Western-like’ and ‘Health conscious’ dietary patterns in toddlers. Br J Nutr. 2013;109:137–47.

Braddon KE, Keown-Stoneman CD, Dennis CL, Li X, Maguire JL, O’Connor DL, et al. Maternal Preconception body mass index and early childhood nutritional risk. J Nutr. 2023;153:2421–31.

Carsley S, Borkhoff CM, Maguire JL, Birken CS, Khovratovich M, McCrindle B, et al. Cohort profile: the applied research group for kids (TARGet Kids!). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:776–88.

World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards: training course on child growth assessment [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43601

Randall Simpson JA, Keller HH, Rysdale LA, Beyers JE. Nutrition screening tool for every preschooler (NutriSTEPTM): validation and test–retest reliability of a parent-administered questionnaire assessing nutrition risk of preschoolers. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:770–80.

Randall Simpson J, Gumbley J, Whyte K, Lac J, Morra C, Rysdale L, et al. Development, reliability, and validity testing of Toddler NutriSTEP: a nutrition risk screening questionnaire for children 18-35 months of age. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab Physiol Appl Nutr Metab. 2015;40:877–86.

Omand J, Janus M, Maguire J, Parkin P, Aglipay M, Simpson J, et al. Nutritional risk in early childhood and school readiness. J Nutr. 2021;151:3811–9.

VanderWeele TJ. Mediation analysis: a practitioner’s guide. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:17–32.

VanderWeele T. Explanation in causal inference: methods for mediation and interaction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. p. 729.

French SA, Tangney CC, Crane MM, Wang Y, Appelhans BM. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: the SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:231.

Roustaei Z, Räisänen S, Gissler M, Heinonen S. Socioeconomic differences in the association between maternal age and maternal obesity: a register-based study of 707,728 women in Finland. Scand J Public Health. 2022;51:963–71.

Wemakor A, Garti H, Azongo T, Garti H, Atosona A. Young maternal age is a risk factor for child undernutrition in Tamale Metropolis, Ghana. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:877.

Shai I, Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, et al. Ethnicity, obesity, and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1585–90.

de Hoog MLA, Kleinman KP, Gillman MW, Vrijkotte TGM, van Eijsden M, Taveras EM. Racial/ethnic and immigrant differences in early childhood diet quality. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1308–17.

Ugwuja EI, Nnabu RC, Ezeonu PO, Uro-Chukwu H. The effect of parity on maternal body mass index, plasma mineral element status and new-born anthropometrics. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:986–92.

Potter C, Gibson EL, Ferriday D, Griggs RL, Coxon C, Crossman M, et al. Associations between number of siblings, birth order, eating rate and adiposity in children and adults. Clin Obes. 2021;11:e12438.

Government of Canada SC. Statistics Canada. 2022 [cited 2023 Feb 15]. 2021 Census of Population - Toronto, City (C) [Census subdivision], Ontario. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Eny KM, Chen S, Anderson LN, Chen Y, Lebovic G, Pullenayegum E, et al. Breastfeeding duration, maternal body mass index, and birth weight are associated with differences in body mass index growth trajectories in early childhood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107:584–92.

Buuren Svan, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67.

van Buuren S. Flexible imputation of missing data. Second edition. (International and comparative criminal justice series). Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC, an imprint of Taylor and Francis; 2018.

Steen J, Loeys T, Moerkerke B, Vansteelandt S. Medflex: an R package for flexible mediation analysis using natural effect models. J Stat Softw. 2017;76:1–46.

Zeileis A, Köll S, Graham N. Various versatile variances: an object-oriented implementation of clustered covariances in R. J Stat Softw. 2020;95:36.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/

Weir CB, Jan A. BMI classification percentile and cut off points. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 [cited 2022 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541070/

Perez MR, de Castro LS, Chang YS, Sañudo A, Marcacine KO, Amir LH, et al. Breastfeeding Practices and problems among obese women compared with nonobese women in a Brazilian hospital. Women’s Health Rep. 2021;2:219–26.

Preusting I, Brumley J, Odibo L, Spatz DL, Louis JM. Obesity as a predictor of delayed lactogenesis II. J Hum Lact. 2017;33:684–91.

Nommsen-Rivers LA, Wagner EA, Roznowski DM, Riddle SW, Ward LP, Thompson A. Measures of maternal metabolic health as predictors of severely low milk production. Breastfeed Med J Acad Breastfeed Med. 2022;17:566–76.

Dennis CL. Theoretical underpinnings of breastfeeding confidence: a self-efficacy framework. J Hum Lact J Int Lact Consult Assoc. 1999;15:195–201.

Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:142–54.

Kair LR, Colaizy TT. Obese mothers have lower odds of experiencing pro-breastfeeding hospital practices than mothers of normal weight: CDC Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2004-2008. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:593–601.

DiSantis KI, Collins BN, Fisher JO, Davey A. Do infants fed directly from the breast have improved appetite regulation and slower growth during early childhood compared with infants fed from a bottle? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:89.

Larsen JK, Bode L. Obesogenic programming effects during lactation: a narrative review and conceptual model focusing on underlying mechanisms and promising future research avenues. Nutrients. 2021;13:299.

Yelverton CA, Geraghty AA, O’Brien EC, Killeen SL, Horan MK, Donnelly JM, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal eating behaviours are associated with child eating behaviours: findings from the ROLO Kids Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:670–9.

Taveras EM, Scanlon KS, Birch L, Rifas-Shiman SL, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Association of breastfeeding with maternal control of infant feeding at age 1 year. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e577–583.

Orr SK, Dachner N, Frank L, Tarasuk V. Relation between household food insecurity and breastfeeding in Canada. CMAJ. 2018;190:E312–9.

Thulier D, Mercer J. Variables associated with breastfeeding duration. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38:259–68.

Cohen AK, Rai M, Rehkopf DH, Abrams B. Educational attainment and obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14:989–1005.

Headen I, Cohen AK, Mujahid M, Abrams B. The accuracy of self-reported pregnancy-related weight: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2017;18:350–69.

Brownell EA, Hagadorn JI, Lussier MM, Goh G, Thevenet-Morrison KN, Lerer TJ, et al. Optimal periods of exclusive breastfeeding associated with any breastfeeding duration through one year. J Pediatr. 2015;166:566–.e1.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following sources of support; Clinician Scientist Training Program Scholarship (CSTP), Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and the Edwin S.H. Leong Centre for Healthy Children. We thank all of the participating families for their time and involvement in TARGet Kids! and are grateful to all practitioners who are currently involved in the TARGet Kids! practice-based research network.

Members of the TARGet Kids! Collaboration:

Co-Leads: Catherine S. Birken, MD, and Jonathon L. Maguire, MD.

Executive Committee: Christopher Allen, BSc; Laura N. Anderson, PhD; Danielle D’Annunzio, BA, LLM, PMP; Mateenah Jaleel, BSc; Charles Keown-Stoneman, PhD; Natricha Levy McFarlane, MPhil; Jessica A. Omand RD, PhD; and Sharon Thadani, MLA/T.

Investigators and Trainees: Mary Aglipay, MSc; Imaan Bayoumi, MD MSc; Cornelia M. Borkhoff, PhD; Sarah Carsley, PhD; Alice Charach, MD; Katherine Cost, PhD; Curtis D’Hollander RD MSc; Anne Fuller, MD; Laura Kinlin, MD MPH; Michaela Kucab RD, MSc; Patricia Li, MD MSc; Pat Parkin, MD; Nav Persaud, MD MSc; Sarah Rae, BHSc, MSc; Izabela Socynska, RD MSc; Shelley Vanderhout, RD PhD; Leigh Vanderloo, PhD; and Peter Wong, MD PhD.

Research Staff: Piyumi Konara Mudiyanselage, MSc; Xuedi Li, MSc; Jenny Liu, BHSc; Michelle Mitchell, BA; Yulika Yoshida-Montezuma, MPH; and Nusrat Zaffar, MBBS.

Clinical Site Research Staff: Trudy-Ann Buckley, BSc; Pamela Ruth Flores, MD; Kardelen Kurt, BSc; Sangeetha Loganathan, BPT; Tarandeep Mali, BSc; and Laurie Thompson, MLT.

Parent Partners: Jennifer Batten; Jennifer Chan; John Clark; Amy Craig; Kim De Castris-Garcia; Sharon Dharman; Sarah Kelleher; Salimah Nasser; Tammara Pabon; Michelle Rhodes; Rafael Salsa; Julie Skelding; Daniel Stern; Kerry Stewart; Erika Sendra Tavares; Shannon Weir; and Maria Zaccaria Cho.

Offord Centre for Child Studies Collaboration: Principal Investigator: Magdalena Janus, PhD; Co-investigator: Eric Duku, PhD; Research Team: Caroline Reid-Westoby, PhD; Patricia Raso, MSc; and Amanda Offord, MSc.

Site Investigators: Emy Abraham, MD; Sara Ali, MD; Kelly Anderson, MD; Gordon Arbess, MD; Jillian Baker, MD; Tony Barozzino, MD; Sylvie Bergeron, MD; Gary Bloch, MD; Joey Bonifacio, MD; Ashna Bowry, MD; Caroline Calpin, MD; Douglas Campbell, MD; Sohail Cheema, MD; Elaine Cheng, MD; Brian Chisamore, MD; Evelyn Constantin, MD; Karoon Danayan, MD; Paul Das, MD; Viveka De Guerra, MD; Mary Beth Derocher, MD; Anh Do, MD; Kathleen Doukas, MD; Anne Egger, BScN; Allison Farber, MD; Amy Freedman, MD; Sloane Freeman, MD; Sharon Gazeley, MD; Karen Grewal, MD; Charlie Guiang, MD; Dan Ha, MD; Curtis Handford, MD; Laura Hanson, BScN, RN; Leah Harrington, MD; Sheila Jacobson, MD; Lukasz Jagiello, MD; Gwen Jansz, MD; Paul Kadar, MD; Lukas Keiswetter, MD; Tara Kiran, MD; Holly Knowles, MD; Bruce Kwok, MD; Piya Lahiry, MD; Sheila Lakhoo, MD; Margarita Lam-Antoniades, MD; Eddy Lau, MD; Denis Leduc, MD; Fok-Han Leung, MD; Alan Li, MD; Patricia Li, MD; Roy Male, MD; Aleks Meret, MD; Elise Mok, MD; Rosemary Moodie, MD; Katherine Nash, BScN, RN; James Owen, MD; Michael Peer, MD; Marty Perlmutar, MD; Navindra Persaud, MD; Andrew Pinto, MD; Michelle Porepa, MD; Vikky Qi, MD; Noor Ramji, MD; Danyaal Raza, MD; Katherine Rouleau, MD; Caroline Ruderman, MD; Janet Saunderson, MD; Vanna Schiralli, MD; Michael Sgro, MD; Hafiz Shuja, MD; Farah Siam, MD; Susan Shepherd, MD; Cinntha Srikanthan, MD; Carolyn Taylor, MD; Stephen Treherne, MD; Suzanne Turner, MD; Fatima Uddin, MD; Meta van den Heuvel, MD; Thea Weisdorf, MD; Peter Wong, MD; John Yaremko, MD; Ethel Ying, MD; Elizabeth Young, MD; and Michael Zajdman, MD.

Applied Health Research Centre: Esmot Ara Begum, PhD; Peter Juni, MD, University of Toronto, Gurpreet Lakhanpal, MSc, CCRP, PMP; Gerald Lebovic, PhD, University of Toronto, Ifeayinchukwu (Shawn) Nnorom, BSc; Marc Denzel Nunez, HBSc; Audra Stitt, MSc; and Kevin Thorpe, MMath.

Mount Sinai Services Laboratory: Raya Assan, MSc, MLT; Homa Bondar, BSc; George S. Charames, PhD, FACMG; Andrea Djolovic, MSc, CCGC; Chelsea Gorscak-Dunn; Mary Hassan, MLT; Rita Kandel, MD; and Michelle Rodrigues, BSc, MLT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KEB, CDGK-S, CSB, DLOC, JLM: Designed research (project conception, development of overall research plan, and study oversight); KEB: Conducted research; CKS, JRS: Provided essential materials (research database, questionnaires); KEB, CDGK-S, XL: Preformed statistical analyses; KEB: Wrote paper; KEB, CSB: Had primary responsibility for final content; CLD, JAO, JRS, XL, CDGK-S, CSB, DLOC, JLM: provided expertise review and feedback on manuscript content; All authors read and approved manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

CSB reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institute for Health Research Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Physician Services Inc, The Edwin S.H. Leong Centre for Healthy Children, University of Toronto and Hospital for Sick Children, Centre for Addictions and Mental Health, Ontario Child Health Support Unit (OCHSU) Impact Child Health Award, and a Walmart Community Grant through the SickKids Foundation for a study on food insecurity in the inpatient hospital setting. JLM received an unrestricted research grant for a completed investigator-initiated study from the Dairy Farmers of Canada (2011–2012) and D drops provided non-financial support (vitamin D supplements) for an investigator-initiated study on vitamin D and respiratory tract infections (2011–2015). CLD reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institute for Health Research. JRS reported receiving grant support from the Canadians Institutes of Health Research, the Danone Institute of Canada, the Canadian Foundation for Dietetic Research, and the Canadian Home Economics Foundation. The other authors had no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Braddon, K.E., Keown-Stoneman, C.D.G., Dennis, CL. et al. The mediation effect of breastfeeding duration on the relationship between maternal preconception BMI and childhood nutritional risk. Eur J Clin Nutr (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-024-01420-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-024-01420-0