Abstract

Introduction

The consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPF) has increased over the past few decades. However, few studies have investigated the association between UPF consumption and cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents from developing countries.

Objective

To evaluate the association between UPF consumption and cardiometabolic risk factors in Brazilian adolescents.

Methods

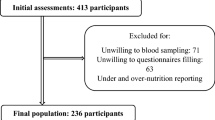

This study included students aged 12–17 years who participated in the ERICA. Food consumption was assessed using a 24-h food recall, and the foods were classified based on their degree of processing, utilizing the NOVA classification. Participants’ blood samples were collected after an overnight fast and exams were performed (triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL-c, LDL-c, fasting glucose, insulin, and HbA1c). Overweight/obesity and blood pressure were also investigated. Associations were evaluated using Poisson regression models.

Results

The analysis included a total of 36,952 adolescents. The energy consumption from UPF was 30.7% (95%CI: 29.7–31.6) per day. Adolescents with high UPF consumption, defined as the top tertile (≥38.7% per day), were observed to have higher intake of sodium, saturated and trans-fat, while having lower intake of proteins, fibers, polyunsaturated fats, vitamins and minerals. After adjusting for potential confounders, it was observed that higher UPF consumption was directly associated with high LDL-c (PR = 1.012; 95%CI: 1.005–1.029) and inversely with low HDL-c (PR = 0.972; 95%CI: 0.952–0.993). No associations were found between UPF consumption and other cardiometabolic risk factors.

Conclusion

Brazilian adolescents have presented a high consumption of UPF, which is associated to poor diet quality and can contribute to elevated LDL-c levels.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The databank of this study contains information that could serve as a potential source of identification of the participants, especially at the schools where the data collection was performed and in cities where only one school participated. Thus, to fulfill the criteria imposed by the institutional review board of the Institute of Collective Health Studies, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and the institution review boards of each unit of the Federation of Brazil, the storage, management, and availability of the databank has been kept restricted by the central team of the Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents (ERICA) (contact via the publication committee at ericapublica@gmail.com or www.erica.ufrj.br).

References

Sbaraini M, Cureau FV, Ritter JDA, Schuh DS, Madalosso MM, Zanin G, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among Brazilian adolescents over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:6415–26.

Telo GH, Cureau FV, Szklo M, Bloch KV, Schaan BD. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes among adolescents in Brazil: findings from Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents (ERICA). Pediatr Diabetes. 2019;20:389–96.

Bloch KV, Klein CH, Szklo M, Kuschnir MC, Abreu Gde A, Barufaldi LA, et al. ERICA: prevalences of hypertension and obesity in Brazilian adolescents. Rev Saúde Públ. 2016;50:9s.

Sommer A, Twig G. The impact of childhood and adolescent obesity on cardiovascular risk in adulthood: a systematic review. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18:91.

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac JC, Levy RB, Louzada MLC, Jaime PC. The UN decade of nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:5–17.

Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM, Castro IRR, de Cannon G. A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. Cad Saúde Públ. 2010;26:2039–49.

IBGE. Household budget survey 2008–2009: nutritional assessment of household food availability in Brazil/IBGE, Coordination of Work and Income.

IBGE. Household budget survey: 2017–2018: analysis of personal food consumption in Brazil / IBGE, Work and Income Coordination.

Rocha LL, Gratão LHA, Carmo ASD, Costa ABP, Cunha CF, Oliveira TRPR, et al. School type, eating habits, and screen time are associated with ultra-processed food consumption among Brazilian adolescents. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121:1136–42.

Costa CDS, Flores TR, Wendt A, Neves RG, Assunção MCF, Santos IS, et al. Sedentary behavior and consumption of ultra-processed foods among Brazilian adolescents: National School Health Survey (PeNSE), 2015. Cad Saúde Pública. 2018;34:e00021017.

Appannah G, Pot GK, Huang RC, Oddy WH, Beilin LJ, Mori TA, et al. Identification of a dietary pattern associated with greater cardiometabolic risk in adolescence. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:643–50.

Monteles NL, dos Santos OK, Gomes KRO, Pacheco RMT, Gonçalves FK, de M, et al. The impact of consumption of ultra-processed foods on the nutritional status of adolescents. Rev Chil Nutr. 2019;46:429–35.

Rauber F, Campagnolo PDB, Hoffman DJ, Vitolo MR. Consumption of ultra-processed food products and its effects on children’s lipid profiles: a longitudinal study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:116–22.

Tavares LF, Fonseca SC, Garcia Rosa ML, Yokoo EM. Relationship between ultra-processed foods and metabolic syndrome in adolescents from a Brazilian Family Doctor Program. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:82–7.

Falcão RCTMA, Lyra CO, Morais CMM, Pinheiro LGB, Pedrosa LFC, Lima SCVC, et al. Processed and ultra-processed foods are associated with high prevalence of inadequate selenium intake and low prevalence of vitamin B1 and zinc inadequacy in adolescents from public schools in an urban area of northeastern Brazil. PloS One. 2019;14:e0224984.

Vasconcellos MT, Silva PL, Szklo M, Kuschnir MC, Klein CH, Abreu Gde A, et al. Sampling design for the Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA). Cad Saude Publ. 2015;31:921–30.

Bloch KV, Cardoso MA, Sichieri R. Study of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Adolescents (ERICA): results and potentiality. Rev Saúde Públ. 2016;50:2s. (Suppl 1)

Barufaldi LA, Abreu Gde A, Veiga GV, Sichieri R, Kuschnir MC, Cunha DB, et al. Software to record 24-hour food recall: application in the study of cardiovascular risks in adolescents. Rev Bras Epidemiol Braz J Epidemiol. 2016;19:464–8.

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Household budget survey 2002–2003: Analysis of household food availability and nutritional status in Brazil. 2004

Conway JM, Ingwersen LA, Vinyard BT, Moshfegh AJ. Effectiveness of the US Department of Agriculture 5-step multiple-pass method in assessing food intake in obese and nonobese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1171–8.

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Household budget survey 2008-2009: Table of nutritional composition of foods consumed in Brazil. 2011

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660–7.

Cureau FV, Bloch KV, Henz A, Schaan CW, Klein CH, Oliveira CL, et al. Challenges for conducting blood collection and biochemical analysis in a large multicenter school-based study with adolescents: lessons from ERICA in Brazil. Cad Saude Publ. 2017;33:e00122816.

Bloch KV, Szklo M, Kuschnir MC, Abreu Gde A, Barufaldi LA, Klein CH, et al. The study of cardiovascular risk in adolescents-ERICA: rationale, design and sample characteristics of a national survey examining cardiovascular risk factor profile in Brazilian adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:94.

Xavier HT, Izar MC, Faria Neto JR, Assad MH, Rocha VZ, Sposito AC, et al. V Brazilian guidelines on dyslipidemias and prevention of atherosclerosis. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013;101:1–20. Suppl 1

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S13–28.

Chissini RBC, Kuschnir MC, de Oliveira CL, Giannini DT, Santos B. Cutoff values for HOMA-IR associated with metabolic syndrome in the Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents (ERICA Study). Nutr Burbank. 2020;71:110608.

Stergiou GS, Yiannes NG, Rarra VC. Validation of the Omron 705 IT oscillometric device for home blood pressure measurement in children and adolescents: the Arsakion School Study. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:229–34.

National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–76. 2 Suppl 4th Report

de Farias JC, Lopes Ada S, Mota J, Santos MP, Ribeiro JC, Hallal PC, et al. Validity and reproducibility of a physical activity questionnaire for adolescents: adapting the Self-Administered Physical Activity Checklist. Rev Bras Epidemiol Braz J Epidemiol. 2012;15:198–210.

Tavares LF, Castro IR, Cardoso LO, Levy RB, Claro RM, Oliveira AF. Validity of indicators on physical activity and sedentary behavior from the Brazilian National School-Based Health Survey among adolescents in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cad Saude Publ. 2014;30:1861–74.

Brazilian Association of Research Companies. Standard criteria for economic classification Brazil. 2008. https://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil.

Barros AJD, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21.

Beserra JB, Soares NIDS, Marreiros CS, Carvalho CMRG, Martins MDCCE, Freitas BJESA, et al. Do children and adolescents who consume ultra-processed foods have a worse lipid profile? A systematic review. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2020;25:4979–89.

Zhu Y, Bo Y, Liu Y. Dietary total fat, fatty acids intake, and risk of cardiovascular disease: a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18:91.

Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2459–72.

Izar MC, de O, Lottenberg AM, Giraldez VZR, Santos Filho RDD, Machado RM, et al. Position statement on fat consumption and cardiovascular health - 2021. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021;116:160–212.

Fournier N, Attia N, Rousseau-Ralliard D, Vedie B, Destaillats F, Grynberg A, et al. Deleterious impact of elaidic fatty acid on ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux from mouse and human macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:303–12.

Ambrosini GL, Oddy WH, Huang RC, Mori TA, Beilin LJ, Jebb SA. Prospective associations between sugar-sweetened beverage intakes and cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:327–34.

Kosova EC, Auinger P, Bremer AA. The relationships between sugar-sweetened beverage intake and cardiometabolic markers in young children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:219–27.

McCourt HJ, Draffin CR, Woodside JV, Cardwell CR, Young IS, Hunter SJ, et al. Dietary patterns and cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents and young adults: the Northern Ireland Young Hearts Project. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:1685–98.

Cuchel M, Rader DJ. Genetics of increased HDL cholesterol levels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1710–12.

Moon JH, Koo BK, Moon MK. Optimal high-density lipoprotein cholesterol cutoff for predicting cardiovascular disease: comparison of the Korean and US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9:334–42.

Saiedullah M, Sha M, Siddique M, Tamannaa Z, Hassan Z. Healthy Bangladeshi individuals having lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level compared to age-, gender-, and body mass index-matched Japanese individuals: a pilot study. J Mol Pathophysiol. 2017;6:1.

Juul F, Martinez-Steele E, Parekh N, Monteiro CA, Chang VW. Ultra-processed food consumption and excess weight among US adults. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:90–100.

Nardocci M, Leclerc BS, Louzada ML, Monteiro CA, Batal M, Moubarac JC. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Canada. Can J Public Health Rev Can Sante Publ. 2019;110:4–14.

Louzada ML, Baraldi LG, Steele EM, Martins AP, Canella DS, Moubarac JC, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Brazilian adolescents and adults. Prev Med. 2015;81:9–15.

Silva FM, Giatti L, de Figueiredo RC, Molina MDCB, de Oliveira Cardoso L, Duncan BB, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed food and obesity: cross sectional results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) cohort (2008-2010). Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:2271–9.

Askari M, Heshmati J, Shahinfar H, Tripathi N, Daneshzad E. Ultra-processed food and the risk of overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Obes. 2020;44:2080–91.

Cunha DB, da Costa THM, da Veiga GV, Pereira RA, Sichieri R. Ultra-processed food consumption and adiposity trajectories in a Brazilian cohort of adolescents: ELANA study. Nutr Diabetes. 2018;8:28.

González-Gil EM, Huybrechts I, Aguilera CM, Béghin L, Breidenassel C, Gesteiro E, et al. Cardiometabolic risk is positively associated with underreporting and inversely associated with overreporting of energy intake among european adolescents: the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence (HELENA) study. J Nutr. 2021;151:675–84.

Schnabel L, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, Touvier M, Srour B, Hercberg S, et al. Association between ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of mortality among middle-aged adults in France. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:490–8.

Fiolet T, Srour B, Sellem L, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, Méjean C, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ. 2018;360:k322.

Srour B, Fezeu LK, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, Méjean C, Andrianasolo RM, et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ. 2019;365:l1451.

Schnabel L, Buscail C, Sabate JM, Bouchoucha M, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, et al. Association between ultra-processed food consumption and functional gastrointestinal disorders: results from the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1217–28.

Mendonça RD, Lopes AC, Pimenta AM, Gea A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M, et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of hypertension in a mediterranean cohort: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra project. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30:358–66.

Srour B, Fezeu LK, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, Debras C, Druesne-Pecollo N, et al. Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Among Participants of the NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:283–91.

Mendonça RD, Pimenta AM, Gea A, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Lopes AC, et al. Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: the University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1433–40.

Fardet A. Minimally processed foods are more satiating and less hyperglycemic than ultra-processed foods: a preliminary study with 98 ready-to-eat foods. Food Funct. 2016;7:2338–46.

Boulangé CL, Neves AL, Chilloux J, Nicholson JK, Dumas ME. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med. 2016;8:1–12.

Calvo MS, Uribarri J. Public health impact of dietary phosphorus excess on bone and cardiovascular health in the general population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:6–15.

Poulsen MW, Hedegaard RV, Andersen JM, de Courten B, Bügel S, Nielsen J, et al. Advanced glycation endproducts in food and their effects on health. Food Chem Toxicol Int J Publ Br Ind Biol Res Assoc. 2013;60:10–37.

Juul F, Vaidean G, Parekh N. Ultra-processed foods and cardiovascular diseases: potential mechanisms of action. Adv Nutr. 2021;12:1673–80.

Canella DS, Louzada MLDC, Claro RM, Costa JC, Bandoni DH, Levy RB, et al. Consumption of vegetables and their relation with ultra-processed foods in Brazil. Rev Saúde Públ. 2018;52:50.

Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4567.

Laitinen TT, Nuotio J, Rovio SP, Niinikoski H, Juonala M, Magnussen CG, et al. Dietary fats and atherosclerosis from childhood to adulthood. Pediatrics. 2020;145:e20192786.

Shoar S, Ikram W, Shah AA, Farooq N, Gouni S, Khavandi S, et al. Non-high-density lipoprotein (non-HDL) cholesterol in adolescence as a predictor of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in adulthood. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021;22:295–9.

Popkin BM, Barquera S, Corvalan C, Hofman KJ, Monteiro C, Ng SW, et al. Towards unified and impactful policies to reduce ultra-processed food consumption and promote healthier eating. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:462–70.

Funding

The ERICA project was financed by the Department of Science and Technology of the Department of Science and Technology and Strategic Inputs of the Ministry of Health (Decit /SCTIE/MS) and the Health Sector Fund (CT–Saúde) of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI) by the Innovation and Research Financing Agency (FINEP: protocol 01090421), and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq: protocols 565037/2010-2, 405009/2012-7 and 457050/2013-6). We thank the Research Incentive Fund at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (FIPE-HCPA–20090098, 20150400 and 20200522). This work was supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel–Brazil (CAPES)–Financing Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMM: Conceptualization, analyzed the data and wrote the paper; NNFM: Analyzed the data and wrote the paper; BMM: Wrote the paper, review & editing; LLR: Analyzed the data and review & editing; LLM: Analyzed the data and review & editing; BDS: Supervision, review & editing; FVC: Conceptualization, supervision, analyzed the data and wrote the paper, review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA) was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committees of all participating centers.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Madalosso, M.M., Martins, N.N.F., Medeiros, B.M. et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cardiometabolic risk factors in Brazilian adolescents: results from ERICA. Eur J Clin Nutr 77, 1084–1092 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-023-01329-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-023-01329-0