Abstract

Environmental degradation due to the carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels has triggered the need for sustainable and renewable energy. Hydrogen has the potential to meet the global energy requirement due to its high energy density; moreover, it is also clean burning. Photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting is a method that generates hydrogen from water by using solar radiation. Despite the advantages of PEC water splitting, its applications are limited by poor efficiency due to the recombination of charge carriers, high overpotential, and sluggish reaction kinetics. The synergistic effect of using different strategies with cocatalyst decoration is promising to enhance efficiency and stability. Transition metal-based cocatalysts are known to improve PEC efficiency by reducing the barrier to charge transfer. Recent developments in novel cocatalyst design have led to significant advances in the fundamental understanding of improved reaction kinetics and the mechanism of hydrogen evolution. To highlight key important advances in the understanding of surface reactions, this review provides a detailed outline of very recent reports on novel PEC system design engineering with cocatalysts. More importantly, the role of cocatalysts in surface passivation and photovoltage, and photocurrent enhancement are highlighted. Finally, some challenges and potential opportunities for designing efficient cocatalysts are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy and the environment are among the most challenging issues today, owing to the continuously escalating need for energy and the deteriorating environment caused by using fossil fuels. On-demand access to plentiful, clean, and renewable energy sources has been projected to be made possible by advanced renewable solar technology and the use of renewable energy sources. Hydrogen, a carbon-free source with a high energy storage density, and its generation through photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting using solar harvesting is the most attractive strategy to address these environmental, energy demand, and supply issues1,2. Since Fujishima and Honda’s work employing TiO2 as a photoanode3 combined with a Pt electrode as a counter electrode for PEC water splitting, immense efforts have been made to construct efficient, robust, and cost-effective PEC water splitting technologies4.

The PEC cell, which typically comprises a cathode and an anode, is capable of decomposing water into H2 and O2 without the need for an external bias by initiating half-cell reactions, oxidation, and reduction at the anode and cathode, respectively. The overengineered semiconductor material film must undergo numerous adjustments in PEC cells. The PEC process involves three major steps: (i) the generation of charge carriers (electron-hole pairs) as a result of light absorption by a semiconductor with an appropriate bandgap; (ii) charge separation and migration to the semiconductor-electrolyte interface; and (iii) the important processes of the surface reactions of water reduction and oxidation5. To improve the PEC performance, great efforts have been made, including various strategies such as bandgap engineering by developing narrow bandgap semiconductors6 that absorb light over a wide range of wavelengths, doping7, heterojunctions8,9, incorporating metal nanoparticles (NPs) for surface plasmon resonance (SPR)10,11, morphological control12, surface passivation13, and decorating cocatalysts14,15. Among all of these, the combination of semiconductors and heterogeneous cocatalysts is one of the most effective approaches to improve PEC performance for solar fuel production.

In hybrid electrodes, cocatalysts do not act as light-absorbing materials; instead, they participate in electrode/electrolyte interface reactions and catalyze the reaction between the photogenerated charge carriers and intermediate ions (H+ and OH−) by providing active surface sites for oxidation and reduction16. However, in the absence of active sites at the interface, charge carriers tend to accumulate, leading to recombination and photocorrosion17. In PEC cells, cocatalysts play a role in accelerating the kinetics of both the OER and HER. The kinetics of these reactions increases in the following two steps: (i) an interface with the semiconductor is developed and photogenerated charge carriers are trapped to facilitate electron-hole separation and (ii) highly active surface sites are provided for the adsorption of ions where the trapped charge carriers are supplied for the reduction or oxidation of water18. The influence of enhanced charge separation and surface catalytic reactions selectively improves the kinetics of the reactions. Among the benefits listed above, cocatalysts prevent recombination and charges from building up at the interface by quickly devouring charge carriers and making the material resistant to photocorrosion by physically separating the semiconductor from the electrolyte19,20.

In addition to noble metal catalysts such as platinum for the HER21 and ruthenium oxide for the OER, a variety of transition metal-based alloys, hydroxides22, oxides23, phosphides24, sulfides25, selenides26, nitrides27, carbides28, borides29, and carbon-based 1D, 2D, and doped carbon materials have been designed to manifest the cocatalyst requirements. Transition metal-based materials, particularly those made of Mo, Co, Ni, and Fe, have been recognized as the most promising catalysts for the HER and OER because of their low-cost and improved catalytic performance that is comparable to that of noble metal cocatalysts30,31,32. The crucial function of cocatalysts emphasizes the significance of choosing certain catalytic materials, developing their interface, and ensuring their selectivity for the reaction at the surface. It is crucial that attention be focused on the interaction between the semiconductor and the cocatalyst for charge carrier transfer and the selectivity of the cocatalyst toward the OER or HER to improve the reaction kinetics16.

This review article presents a detailed discussion of studies based on heterogeneous transition metal-based catalysts as cocatalysts boosting the HER and OER in recently developed PEC systems for water splitting. To date, cocatalyst developments for modern PEC water-splitting applications have received little attention. Emphasis has been put on recently developed effective cathodic and anodic photoelectrodes using photoactive p-type materials such as Cu2O and Si and n-type materials such as BiVO4, Fe2O3, and Si supplemented by cocatalysts. Bifunctional cocatalysts are also discussed in this review. This article will discuss the challenges and opportunities for developing transition metal-based catalysts as flexible cocatalysts for PEC water splitting.

Thermodynamic aspect of PEC water splitting

PEC water splitting decomposes water into hydrogen and oxygen using a thin semiconductor film that generates excited electron-hole pairs when irradiated with light of appropriate energy. The photogenerated charge carriers promote the reaction at the semiconductor-electrolyte interface. Thermodynamically, PEC water splitting involves 285.8 kJ mol−1 energy, which is equal to the amount of energy released when the combustion of hydrogen to liquid water takes place (Eq. 1). The energy is supplied by the Gibbs free energy (237.2 kJ mol−1, the maximum energy that can be extracted from the reaction) and the heat released (48.6 kJ mol−1) by the reaction20. Combustion is a redox reaction involving fuel (H2) and an oxidant (O2) as reactants, resulting in an exothermic reaction producing water vapor. However, considering the reverse reaction (Eq. 2), a certain amount of energy equivalent to Gibb’s free energy (237.2 kJ mol−1) can be supplied to a system containing H2O(l), which can be thermodynamically converted into H2g and O2g.

The Gibb’s free energy (237.2 kJ mol−1) corresponds to 1.23 eV per electron suggesting that the potential overall thermodynamic barrier for a water-splitting reaction is 1.23 V. However, to drive the reaction at a practical rate, the excess heat generated by the reaction must also be considered. When the total energy (285.8 kJ mol−1) is converted to potential, this value becomes 1.48 V, which is called the overpotential. Conventionally, free energy, i.e., 237.2 kJ mol−1 or 1.23 V, is the energy required to dissociate water into H2g and O2g. The theoretical maximum photovoltage that a semiconductor can produce is ~400 mV less than the bandgap under ideal conditions. The photovoltage generated by the photoelectrode (Vph) must be >1.23 V to dissociate the water. Semiconductors with bandgaps >1.6 eV are ideal candidates for PEC applications33.

Understanding the semiconductor-electrolyte interface

The semiconductor-electrolyte immediate contact in a PEC cell is known as the semiconductor-liquid junction (SCLJ) (Fig. 1). The SCLJ creates an electrical double-layer interface due to the difference between the Fermi energy (EF) level of the semiconductor and the redox potential (Eredox) of the electrolyte, resulting in electron transfer occurring from the semiconductor to the electrolyte or vice versa, leading to band bending. Due to band bending, a space charge layer is formed on the semiconductor surface that is in contact with the electrolyte, and the semiconductor is electrically neutral beyond the space charge layer34. The width of the space charge layer can be in the range of 0.1–1 μm [Fig. 1a] and is given by:

where Wsc is the width of the space charge layer, ε is the relative permittivity, ε0 is the permittivity of free space, and Δϕsc is the difference between the Fermi level of the semiconductor in a vacuum and the electrochemical potential of the electrolyte known as the space charge layer (I). ΔϕH and ΔϕG are the potential drops in the Helmholtz layer (II) and Gouy layer (III), respectively35. Additionally, q is the charge of an electron, and Nd is the donor density [Fig. 1a]. The separation and transmission of photogenerated electrons and holes are aided by band bending36. The band bending is upward (depletion layer, i.e., EF > Eredox) in n-type semiconductors and downward (accumulation layer, i.e., EF < Eredox) in p-type semiconductors. Taking a closer look, the minority charge carriers over the surface of the photoelectrodes typically participate in the reaction. For instance, holes (minority charge carriers) can oxidize water at the photoanode for the OER, and electrons (minority charge carriers) can reduce water at the photocathode for the HER. The electrical double-layer formed at the junction is contributed by the Helmholtz layer (OHP and IHP) and the Gouy layer [Fig. 1a]. The space charge layer contributes a potential drop across the semiconductor/electrolyte interface, followed by the Helmholtz and Gouy layers. If we consider n-type semiconductors, electrons move to the electrolyte side when the semiconductor comes in contact with the electrolyte, and the space charge layer becomes positively charged. In contrast, the Helmholtz layer contains electrons in trapped states, solvated ions, and adsorbed ions. The transfer of electrons from the semiconductor to the electrolyte side leads to a shift in E(F,Eq) (equilibrium Fermi redox potential) toward a downward position, and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital of the electrolyte remains at a position until equilibrium is established [Fig. 1b]. Since the space charge layer becomes depleted as the electron concentration and excess holes accumulate near the surface, this region is termed the depletion region, and the bands bend in the upward direction. On the other hand, for p-type semiconductors (Ef < Eredox), electrons are transferred from the highest occupied molecular orbital of the electrolyte to the semiconductor, and the concentration of electrons increases in the space charge layer, which is termed as the accumulation layer. E(F,Eq) begins to rise upward due to the accumulation of electrons near the surface, causing band bending downward [Fig. 1b]. In upward band bending, the semiconductor can switch to a p-type semiconductor if the electrons are depleted to below the intrinsic level. This condition of the space charge region is known as the inversion layer36.

a Model of the double-layer structure of an n-type semiconductor electrode in contact with the electrolyte under equilibrium conditions. Reproduced with permission from ref. 35. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. b Energy diagram of n-type and p-type semiconductors before and after partial and equilibrium chemisorption on the surface. Reproduced with permission from ref. 36. Copyright 2012, American Chemical Society.

Working principle of PEC water splitting

Basic PEC water splitting involves four steps: (i) light absorption, (ii) charge carrier generation, (iii) charge carrier separation, and (iv) charge carrier transport to the SCLJ for the surface reaction. Light is absorbed by the semiconductors of the appropriate bandgap, as described earlier. The absorption of light excites the electron-hole pairs, which are then separated. The electron then migrates toward the photocathode, leaving behind a hole. The recombination of electron-hole pairs is a significant obstacle in PEC water splitting. It is essential that the conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) in the semiconductor are in the proper positions for the reduction or oxidation of water molecules. For the HER reaction, the CB of the semiconductor must be more negative than the reduction potential of H+ (ECB < E0red), while the VB must be more positive than the water oxidation potential (EVB > E0ox).

Solar-driven PEC reactions occurring at photoelectrodes require a potential window of 1.23 V to split water into H2 and O2. The water-splitting reaction involves the oxidation of water with the consumption of four electrons for the OER and a two-electron process to reduce the protons for the HER. The half-cell reactions are shown in the following equations:

The potential for H2 evolution is 0 VNHE, while for O2 evolution, it is 1.23 V, giving ΔE0 = 1.23 V. The pH of the electrolyte also plays a role in the shift in the oxidation and reduction potential of water. The slope of the graph of pH versus potential gives a value of −59 mV/pH according to the Nernst equation, meaning that a unit change in pH decreases the water’s oxidation/reduction potential by ~59 mV.

The water-splitting reaction in the acidic electrolyte is shown in Eqs. 3 and 4

The water-splitting reaction in the basic electrolyte is presented in Eqs. 5 and 6

Required properties of the semiconductor

Photoactive materials, i.e., semiconductor thin films, play a vital role in PEC water splitting. The redox potential gap requirement is 1.23 V, met via the photoexcitation of semiconductor films by light-matter interactions. Typically, the charge carriers, in this case, must have sufficient overpotential to perform the reactions at the photoanode and photocathode. The semiconductor can generate a photovoltage of ~400 mV below its bandgap under experimental conditions37. Therefore, a semiconductor must possess an ideal bandgap range of 1.6–2.6 eV to absorb light from solar radiation and effectively drive the OER and HER through the potential barrier38,39.

Most n-type semiconductors, such as TiO2, CdS, SrTiO3, g-C3N4, and ZrO2, have a very suitable band-edge position for the OER. However, with their wide bandgap, the PEC efficiency is very low compared to narrow bandgap semiconductors5. Narrow bandgap p-type semiconductors such as Cu2O, Cu2S, Sb2Se3, p-Si, and CuInS2 have CB edges suitable for photocathodes, and their bandgaps are optimal for light absorption40. On the other hand, n-type semiconductors, such as BiVO4, WO3, and Fe2O3, have suitable visible light absorption and feasible VB edges for the oxygen evolution reaction41.

Emerging cocatalysts for the HER

Earth-abundant, inexpensive, and reliable cocatalysts are the focus of recent developments in PEC water-splitting systems. For the HER, several Mo, Ni, Co, and Fe metal complexes are used within the photocathode. The H+ ions adsorb to the cocatalyst’s surface in this process, and an electron from a semiconductor that has been photoexcited reduces the H+ ion to H2 gas. Active surface sites are those locations where the H+ ions are absorbed. Pt is regarded as the benchmark ideal catalyst for the HER. However, its usefulness is constrained by its high cost and poor availability.

The shape, size, morphology, optical transparency, crystal structure, active sites for H+ adsorption, surface area, creation of defects to modulate electronic structure, and introduction of foreign atoms are just a few of the variables that affect the selectivity and activity of transition metal-based cocatalysts. The HER activity on the surface is controlled by the size and shape of the NPs. Co-P with nanowire, nanosheet, and nanoparticle morphologies was used to study morphology-dependent hydrogen evolution. The maximum activity and stability for hydrogen evolution were shown with Co-P nanowires42. The most crucial factor in choosing the PEC-HER cocatalyst is the number of active surface sites and surface area. The MoS2 active surface locations for H atoms and sulfur vacancy adsorption control the activity and greatly lower the overpotential. MoS2 comes in three different forms: 1H, 2 T, and amorphous; however, the crystal structure also has a significant impact on its activity. Each of these three forms differs in the length and angle of the Mo-Mo and MoS bonds, which have a significant impact on each form’s activity and stability toward the HER43. Based on the photocurrent in the a-Si/Mo2C photocathode, the thickness of the cocatalyst layer controls the kinetics of the HER as well as light absorption and charge generation44. The introduction of P into NiS and the creation of sulfur vacancies enhanced the activity of P-doped NiS and reduced the overpotentials for the HER and OER, respectively. Modulation of the electronic structure and sulfur vacancy defects resulted in the optimization of the adsorption-free energy of hydrogen (ΔGH*) and oxygen-containing intermediates45.

Mo-based cocatalysts for the HER

Bulk and mono- or few-layer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs), such as MoS246, MoSe226, and Mo2C28, have been used for various applications, including in electronic devices, optoelectronics47, sensing48, energy storage49, and catalysis30. MoS2 has historically been utilized as an industrial hydrodesulfurization catalyst50, but recently, it has been investigated as a potential alternative to Pt for HER catalysts due to its comparatively high HER catalytic activity, low-cost, abundance on Earth, and high stability.

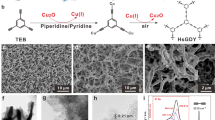

MoS2 is a layered TMDC of the MX2 type, where X is a chalcogen (S, Se, Te). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations predict that the catalytic activity of Pt and MoS2 for the HER is comparable and similar to the [NiFe]-hydrogenase activity for the HER because of the Gibbs free energy of hydrogen adsorption51. Experimental results have shown that the surface-active sites of MoS2 efficiently promote the HER. Generally, two processes are known for synthesizing 2D TMDCs and Si heterojunctions: (i) TMD production on SiO2 followed by transfer to arbitrary substrates such as Si wafers and (ii) direct synthesis of TMDs on an arbitrary substrate. In early reports of MoS2-based cocatalysts for photocathodes, Si was used as the light-absorbing material. Thin-film transfer methods were used to fabricate MoS2/p-Si heterojunctions with thickness-controlled MoS2 layers grown over SiO2/Si substrates using thermolysis8. In addition to the difficult CVD process, various simple fabrication methods have been developed for MoS2-based photocathodes, such as photoassisted electrodeposition of a MoSx layer over a Si substrate. Recently, a SiPN/CN/MoSx photocathode was fabricated, and an N-doped carbon interlayer enhanced the interfacial charge transfer [Fig. 2a]52. This hierarchical heterostructure reduces light reflection and enhances light absorption. SiO2 is generated in SiPN/MoSx on Si by oxidation of the electrolyte. On the other hand, CN facilitates charge transfer and protects Si in SiPN/CN/MoSx. At 0 VRHE, the photocurrent density (−10 mA cm−2 in 0.5 M H2SO4) of SiPN/CN/MoSx was 2.2 times that of SiPN/MoSx and 6.5 times that of SiPN/CN [Fig. 2b]. Moreover, SiPN/CN/MoSx exhibits a higher positive onset potential (Eop, defined as the potential at −1 mA cm−2) than SiPN/MoSx and SiPN, reaching 0.23 VRHE. The J–t curve proved the stability of the SiPN/CN/MoSx photocathode [Fig. 2c]. IPCE measurements at 0 VRHE showed enhanced performance of SiPN/CN/MoSx compared to SiPN, SiPN/CN, and SiPN/MoSx photocathodes [Fig. 2d].

a Schematic representation of the p-Si/CN/MoSx band structure diagram. b LSV curves showing the PEC performance under chopped illumination. c Chronoamperogram curves of the photocathodes. d IPCE measurement of the photocathodes. Reproduced with permission from ref. 52. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

In another study, the direct synthesis of an ultra-pristine p-n junction of MoS2 over p-Si via thermolysis was performed53. The hybrid synthesis procedure involved incorporating the MoO3 layer via evaporation and spin coating of (NH4)2MoS2. This was followed by thermolysis to give MoS2/p-Si. Most reports on MoS2 are based on acidic electrolytes. Recently, MoS2 was decorated over TiO2/Si, and PEC-PV devices were fabricated to study energetically favorable electron transfer through heterojunctions13. The PEC activity of the photocathode was tested in a basic electrolyte (1 M KOH), and TiO2 served as a passivation layer for protection and minimizing the contact of the Si layer with the electrolyte. MoS2 NPs/TiO2 NRs/Si delivered −10 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE and with 180 mV onset potential, which was much higher than that of the TiO2 NRs/Si photocathode (Eonset = 0 mV, J = −1.7 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE). Notably, in acidic medium (0.5 M H2SO4), the MoS2 NPs/TiO2 NRs/Si photocathode achieved a high photocurrent density (−15.2 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE) and onset potential (0.24 VRHE) with good stability up to 30 h. The PEC-PV device was fabricated using a Fe60(NiCo)30Cr10 photoanode and a tandem perovskite/Si solar cell. The unassisted PEC water splitting from the PEC-PV cell exhibited a photocurrent density of −5.4 mA cm−2 with 6.6% STH efficiency in 1 M KOH.

The edge sites in MoS2 are more prone to adsorbing hydrogen for catalysis than the inert basal plane. Moderate hydrogen-binding edge sites terminated with Mo show the best HER performance. The octahedrally coordinated 1T-MoS2 has a higher H binding and releasing affinity than the trigonally coordinated 2H-MoS225. A strategy to reduce the interlayer potential barrier to boost electron transfer and enhance the electrocatalytic activity of MoS2 was previously reported. A MoS2 moiré superlattice with a twisted angle of 7.3° was successfully fabricated using a simple approach rather than a traditional mechanical stacking process54. Comparative study of the structural and surface properties of 2H-MoS2, 1T-MoS2, and amorphous MoS2 for HER activity was carried out using operando XAS analysis and electronic structure models before and after the electrochemical tests43. The 1 T phase can be formed by intercalation of Li+ and Na+ in 2H-MoS2. The Mo-Mo and MoS bond lengths in polymorphic MoS2 play an essential role in HER activity. Although 1 T and amorphous MoS2 show higher current densities than the 2H-MoS2 phase, the current density decreased with time as Li ions dissolved in the electrolyte during the electrochemical test, and 1T-MoS2 slowly changed to 2H-MoS2. At the same time, amorphous MoS2 retained its HER activity for an extended period. XANES observations indicated that the shorter Mo-Mo bonds in 1 T and amorphous MoS2 play a vital role in the enhancement of HER activity. The changes in the electronic structure of MoS2 (1 T, 2H, and amorphous) were also probed by the partial density of states measurements. The Mo edges of distorted 1T-MoS2 are more active sites for hydrogen adsorption because of the optimum Gibbs free energy and superior intrinsic electronic conductivity. The surface electronic structure probed by XPS before and after operando XAS measurements suggested the transformation of 1T-MoS2 to 2H-MoS2. Although the electronic structure remains similar because of H adsorption, the decline in HER activity might be attributed to the interaction between H (S orbital) with the Mo (d orbital) and S (p orbitals).

Semitransparent MoSxCly- and MoSexCly-based electrocatalysts were decorated over n+pp+Si micro pyramids (MPs) via the CVD method, and the highest photocurrent density (−20.6 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE) was reported in 0.5 M H2SO455. A comparative study on the changes in Si morphology from planar to MPs was reported. However, planar Si coated with MoQxCl (Q = S, Se) electrocatalysts delivered a remarkable photocurrent, but micropyramid-based n+pp+Si decorated with the MoQxCl electrocatalyst showed far increased PEC-HER activity. This activity was attributed to the far superior light-absorbing ability of the Si MPs compared to planar Si and the generation of a much larger photovoltage owing to their built-in p-n junction. The photocurrent density dramatically increased from −35 to −43 mA cm−2 for Si MPs decorated with MoQxCl, while the planar Si-based photocathode delivered −10–20 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE. The onset potential significantly increased for Si MPs compared to planar Si. Impedance studies showed good coupling between the Si and MoQxCl catalysts, an essential phenomenon aiding facile charge transfer. Reports on coupling Mo-based electrocatalysts with precious metal catalysts are well known to improve the PEC-HER activity of electrodes [Fig. 3a, b]. The Ru-MoS2/Ti/n+p-Si photocathode delivered a remarkable photocurrent (−43 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE, Eop = 0.53 VRHE) and impressive STH efficiency (7.28%) compared to MoS2/Ti/n+p-Si (J = − 23 mA cm−2, Eop = 0.34 VRHE), MoS2/Ti/n+p-Si (J = − 36 mA cm−2, Eop = 0.52 VRHE), and Pt/Ti/n+p-Si (J = − 25.6 mA cm−2, Eop = 0.41 VRHE) [Fig. 3c, d]46. DFT calculations revealed that the electronic structural alterations generated by the interaction between Ru and MoS2 impacted electron transport and were responsible for the optimal H* ad-/desorption. MoS2 has active catalytic sites on its edges, while its basal plane is inert. To activate the basal plane of MoS2, a unique heterostructure (MoS2/MoSe2) was fabricated using a two-step solvothermal growth process over SiNW arrays56. MoS2/MoSe2/SiNW showed improved PEC performance (−19.35 mA cm−2 at −1.17 VRHE) as well as increased stability compared to MoS2/SiNW (−16.11 mA cm−2 at −1.17 VRHE) and MoSe2/SiNW (−13.2 mA cm−2 at −1.17 VRHE) [Fig. 3e]. The EIS and Mott-Schottky plots revealed the lowest charge transfer resistance and maximum charge carrier concentration along with a maximum flat-band potential shift on the positive axis for MoS2/MoSe2/SiNW [Fig. 3f, g]. DFT calculations revealed strong hybridization of the Mo 4d orbitals of MoS2, Mo 4d of the MoSe2 layer, and the Si 3p orbital along with significant overlap between Se 4p and Si 3p. The activation of the basal plane of MoS2 was attributed to the difference in the work function of MoSe2 and MoS2, allowing efficient charge transfer.

a Schematic of the fabrication process and b possible charge separation/transfer mechanism on n+p-Si/Ti/Ru-MoS2 (EqFn: electron quasi-Fermi level, EqFp: hole quasi-Fermi level, Voc: photovoltage). c Polarization curves (J−V) of n+p-Si/Ti modified with Ru-MoS2, Ru, and MoS2 and bare n + p-Si/Ti. d Transient photocurrent response of n+p-Si/Ti with different catalysts at 0 VRHE. Produced with the permission of ref. 46. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. e LSV curves, f Nyquist plots, and g Mott-Schottky plots of the SiNW, MoSe2/SiNW, MoS2/SiNW, and MoS2/MoSe2/SiNW photocathodes. Reproduced with permission from ref. 56. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Organometal halide perovskite (OHP) is an absorber material with a uniquely designed layered photocathode structure coated with protective Ti foil and decorated with MoS2 as the HER cocatalyst57. A high STH efficiency (11.07%) was reported with a photocurrent density of the MoS2/Ti foil/OHP photocathode of −20.6 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE, which was greater than that of the Ti foil/OHP photocathode (−18.1 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE) with a stable photocurrent for up to 120 h. The MoS2/Ti foil/OHP photocathode had a higher onset potential (1.02 VRHE) than the bare Ti foil/OHP photocathode (0.77 VRHE). Mo2C layers were magnetron sputtered on amorphous Si, and the PEC-HER activity was examined in 0.1 M H2SO4 and 0.1 M KOH28. Interestingly, at pH = 1 and 14, Mo2C was stable and evolved H2 with a photocurrent density of −11.2 mA cm−2, and the onset potential was slightly higher in acidic medium than in basic medium (0.85 VRHE).

Co-based HER catalysts

Although Mo-based cocatalysts are a viable alternative to noble metal catalysts, benefiting from their capabilities in atomic-scale production and excellent stability in acidic and alkaline media, cocatalysts with more transparent qualities must be introduced to lessen the light blockage caused by cocatalysts. Co-based cocatalysts such as CoxP, CoSx, Co-selenides, Co-N-C composites, and M-Co alloys (M=Ni, Fe, etc.) have been the most investigated and have emerged as excellent water-splitting materials in addition to having superior stability in alkaline media58. Co2P over a Si-inverted pyramid (SiIP@Co2P) photoelectrode [Fig. 4a, b] showed a reasonable photocurrent density (−35.2 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE) and superior stability for up to 150 h [Fig. 4c]59. Varying amounts of Co were magnetically sputtered on a Si substrate during fabrication, followed by phosphorization. Moreover, a lower charge transfer resistance was exhibited for the SiIP@Co2P-4.5 mM photocathode compared to the SiIP@Pt and bare SiIP photocathodes. Ji et al.26 synthesized a novel multisite heterostructured bifunctional electrocatalyst (o-CoSe2/c-CoSe2/MoSe2) that enhances both the HER and OER.

a Schematic illustration of the influence of catalyst loading on the SiIP configuration with a thickness-gradient catalytic/protective layer. b TEM image showing the gradient layer of Co2P. c LSV recorded before and after chronoamperometric testing for 48, 98, and 150 h. LSV was also recorded under chopped illumination after 150 h of testing. Reproduced with permission from ref. 59. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. d Illustration showing the dispersed Co-P over Si with different morphologies. e µP structure at higher magnification showing a range of heights but a consistent shape defined by the 54° angle between the Si and crystallographic planes. f n+p-Si µW with 1200 mC cm−2 Co-P. g LSV curves of planar p-Si, micropyramidal p-Si (μP p-Si), and a p-Si microwire (μW p-Si). Reproduced with permission from ref. 60. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. h Schematic diagram of the anticorrosive mechanism of Co-P/20WSx/Si compared to Co-P/Si without a WSx protective layer. i LSV curves under light and (j) comparison of the onset potentials (Eon) and photocurrent densities at 0 VRHE. Reproduced with permission from ref. 24. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

The deposition of opaque cocatalysts on the surfaces of photoactive absorber materials gives rise to parasitic absorption. Recently, the activity of a Co-P catalyst coated on different morphological Si photocathodes was examined, where the Co-P catalyst was integrated with planar Si (p-Si), micropyramidal p-Si (μP p-Si) and a p-Si microwire (μW p-Si) [Fig. 4d–f]60. Electrodeposition of Co-P onto μW p-Si showed that deposition at high current densities directed deposition to the tip of the microwires, and a larger portion of the surface remained exposed for light absorption, which is in contrast to μP p-Si and planar Si. Planar Si and μP p-Si have lower fill factors and photocurrent densities than μW p-Si due to significant parasitic absorption [Fig. 4g]. The interfacial charge transfer kinetics between the p-Si layer and the Co-P cocatalyst were also relevant. After more than 30 h of operation of the μW p-Si/Co-P photocathode, increased loading of the cocatalyst resulted in the formation of a cocatalyst island, and the limiting photocurrent density remained consistent. Additionally, the thickness of the Co-P cocatalysts and their intrinsic light-blocking phenomenon raise an issue with their utility. Interlayers between the semiconductor and cocatalyst improve the PEC performance by providing protection and facilitating charge transfer. Recently, a self-assembled WSx-protected planar Si photocathode loaded with antireflective Co-P cocatalyst was deposited using photoassisted electrodeposition for PEC-HER in an alkaline medium (1 M KOH) [Fig. 4h]24. The integrated Co-P/WSx/Si photocathode delivered outstanding PEC performance (Eop = 0.47 VRHE, Jmax = −25.1 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE) [Fig. 4i] with a durability of 300 h at 0 VRHE. Effective electron transfer resulted in a higher onset potential [Fig. 4j] and photocurrent [Fig. 4i, j], and surface passivation using the cocatalyst played a significant role in boosting PEC longevity.

To assemble the overall water-splitting device, the operating conditions, such as pH, for the OER at the photoanode and HER at the photocathode must be mutually compatible. Photoanodes show high PEC performance in basic media, so it is equally important to develop highly stable photocathodes with remarkable PEC performance in basic electrolytes. A hierarchical photocathode was fabricated by intercalating N-doped graphene between Si and TiO2 layers61. Deposition of Ni/Co phosphide catalyst (NiCoP) on top of Si/CN/TiO2(ALD/NR) exhibited excellent PEC performance (Eop = 0.47 V, Jmax = −19.87 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE) in alkaline medium. The Si/CN/TiO2(ALD/NR)/NiCoP photocathode showed a positive shift to ~487 mV of potential to reach −5 mA cm−2 compared to Si/CN/TiO2(ALD/NR). The photocathode photovoltage (Vph) findings suggest that cocatalyst loading enhanced Vph from 0.22 V to 0.46 V. The band bending in the presence of cocatalyst occurred in such a manner to support the excited-state charge transfer to facilitate a higher photocurrent, stability, and Vph of the photoelectrode.

Ni-based HER catalysts

Ni-based complexes such as NiSx62,63, NiSe264, Ni65, phosphides66, and Ni layer double hydroxides (LDHs)67 have recently attracted attention as nonprecious cocatalysts. According to DFT calculations, Ni2P has an active-site feature similar to that of hydrogenase enzymes, which occurs through a synergistic effect between the exposed proton-acceptor and hydride-acceptor centers on the (001) facet of the Ni2P crystal68. Since 2014, NiP2 has gained attention in HER electrocatalysis. Chen and coworkers integrated NiP2 with a textured pn+-Si photocathode for efficient and sustained PEC hydrogen evolution [Fig. 5a]. The NiP2/Ti/pn+-Si photocathode in acidic and neutral electrolytes showed enhanced PEC activity66. The NiP2/Ti/pn+-Si photocathode delivered an enhanced photocurrent density (−12 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE) [Fig. 5c] with 2.6% HC-STH efficiency and 6 h of durability without significant decay in the photocurrent. A strongly coupled semiconductor-cocatalyst interface was provided by the on-surface synthesis of a particulate NiP2 cocatalyst layer on the photocathode, which enabled charge transfer and accelerated the HER [Fig. 5b]. The pyramidal textured pn+-Si buried junction has a large built-in potential to improve the separation of photogenerated electrons and holes. In addition to NiP2, various nickel-based complexes (Ni2P, Ni12P5, Ni3P, Ni7P3, Ni5P4) and phosphorus-rich nickel phosphides (NiP3) are known to facilitate HERs and OERs. Phosphorus-rich nickel phosphides with higher P/Ni ratios have demonstrated high activity toward the HER, while metal-rich nickel phosphides with low P/Ni ratios have shown good catalytic activity toward the OER. Different phases of nickel phosphide retain different crystallographic facets and crystal structures, giving unique catalytic activity on the surface. Low-cost nickel phosphide (Ni12P5) cocatalyst NPs were synthesized via a hot injection method and were decorated on SiNWs for the EC-HER and PEC-HER [Fig. 5d]69. The Ni12P5/SiNW photocathode was found to be more active than the SiNW/Pt NP photocathode. As a result, the Ni12P5/SiNW photocathode showed a markedly enhanced photocurrent current density (J = −21.0 mA cm−2), open circuit potential (Eoc = 0.40 V), and photoconversion efficiency (2.97%) for 1 h compared to those of pristine SiNWs (J = −1.4 mA cm−2, EOC = 0.3 V, and PCE = 0.0845%) [Fig. 5e]. The loading amount of NiP2 over pn+Si also affected the photocurrent density [Fig. 5f].

a Schematic illustration of the procedure for the synthesis of the textured pn+-Si/Ti/NiP2 photocathode and its HER mechanism. b Energy band diagram of pn+-Si/Ti/NiP2. c LSV curve of pn+-Si/Ti/NiP2 in the light vs. dark. Reproduced with permission from ref. 66. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. d Schematic illustration of Si nanowires decorated with Ni12P5. e LSV curves of SiNWs and Ni12P5/SiNWs measured in the dark and under illumination (100 mW cm−2). f LSV curves with different loadings of Ni12P5 on Si nanowires. Reproduced with permission from ref. 69. Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society.

Among Ni-based cocatalysts, nickel sulfides (NiSx) have received great attention as candidates for replacing Pt in the PEC-HER due to their improved catalytic properties70. A sandwiched CuInS2 between a hole transporting layer (NiO) and HER cocatalyst (NiS) was fabricated [Fig. 6a]63. The NiS/CuInS2/NiO photocathode demonstrated higher PEC performance (J = −2.23 mA cm−2 at −0.6 VRHE) compared to the pristine CuInS2 photocathode [Fig. 6b]. The surface photovoltage [Fig. 6d, e] And IPCE measurements showed that NiS/CuInS2/NiO delivered a higher photovoltage and IPCE efficiency than CuInS2 and the CuInS2/NiO photocathode [Fig. 6c]. Various methods have been discovered to synthesize NiS; for instance, NiS NPs were decorated on Al NPs/Cu2O through the SILAR method, where the Al NPs act as plasmonic sensitizers that can increase light harvesting and generate hot electrons62. NiS facilitated charge separation and the HER [Fig. 6f]. The fabricated photocathode Al NPs/Cu2O/NiS showed an 8-fold increase in photocurrent density (−5.16 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE) compared to the pristine Cu2O photocathode [Fig. 6g]. The NiS loading on Al NPs/Cu2O enhanced Vph and interfacial electric fields [Fig. 6h]. Ni-based hybrid materials are also promising cocatalysts. For instance, a NiS2/NiS heterojunction (NNH) was deposited on planar Si to achieve progressive electron transfer71. The NNH/Si photocathode delivered remarkable PEC performance compared to both the NiS2/Si and NiS/Si photocathodes in 0.5 M H2SO4. The enhanced hydrogen evolution was attributed to the promotion of electron transfer via a progressive transfer system favored by the heterogenic NNH nanostructure, in which photogenerated electrons were transferred from planar p-Si to Ni2+ in the NiS phase and Ni2+ and/or S22− in the defect-rich NiS2 phase. The current–time profiles at 0 VRHE of the as-prepared samples indicate that the durability of NNH/Si at >7 h is much better than those of the other two photocathodes. The good catalytic behavior toward the HER is due to the presence of well-defined exposed facets and the proper proportion of Ni and P atoms.

a Schematic representation of a PEC cell consisting of NiO/CuInS2/NiS as the photocathode and Pt as the counter electrode and the charge transfer mechanism. b LSV curves under continuous illumination. c IPCE (%). d, e Surface photovoltage (SPV) with back and front illumination with SPV configurations, respectively. Reproduced with permission from ref. 63. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. f Schematic illustration of the Al/Cu2O/NiS photocathode with the HER mechanism over NiS. g LSV curves under continuous illumination. h SPV of bare Cu2O, Cu2O/NiS, Al/Cu2O, and Al/Cu2O/NiS photocathodes. Reproduced with permission from ref. 62. Copyright 2020, Elsevier.

Nickel selenides (NiSex) are promising candidates for PEC-HER cocatalysts with different polymorphic phases. Recently, Lee and coworkers proposed a bifunctional catalyst by decorating orthorhombic (o-NiSe2), cubic (c-NiSe2), and hexagonal (h-NiSe2) nanocrystals (NCs) over a Si nanowire (NW) array [Fig. 7(a, b)]64. Among the polymorphic NiSe2 NCs, o-NiSe2 over SiNWs showed excellent PEC activity. The onset potential and photocurrent density of o-NiSe2 (J = −6.7 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE, Eop = 0.2 V) were higher than those of c- and h-NiSe2. o-NiSe2 showed higher activity (J = 5.6 mA cm−2 at 1.23 VRHE and Eop = 0.4 VRHE) than c-NiSe2/n-Si and h-NiSe2/n-Si [Fig. 7c]. This pioneering work showed that o-NiSe2 could be used as a bifunctional cocatalyst for the HER and OER in PEC water splitting [Fig. 7c, d]. The degradation of photoabsorber material under alkaline conditions reduces light absorption by the catalyst layer following frontside illumination. Furthermore, the chemical incompatibility of the interface, mismatch in interfacial energetics, induced interfacial defect states, and recombination sites pose problems to interface engineering between the catalyst layer and semiconductor substrate inside the photocathode. In this regard, nickel sulfides (Ni3S2) have been a hotspot in the study of electrocatalysis due to their excellent electrical conductivity, HER activity, and stability under alkaline conditions. A gradient-structured Ni3S2 (G-Ni3SxO2−x) layer was added via a thermoelectrodeposition method, which acts as a passivation layer as well as the PEC-HER catalyst coated over p-Si [Fig. 7e]72. In a 1 M NaOH aqueous solution, G-Ni3SxO2–x/p-Si demonstrated extraordinary PEC performance, with a noteworthy onset potential (Eop = 0.39 VRHE) and a photocurrent density of −33.8 mA cm−2 at 0 VRHE. The Ni3S2/p-Si photocathode tested at 0 VRHE delivered a degrading photocurrent within a few hours. In contrast, G-Ni3SxO2–x/p-Si underwent the PEC-HER at 0 VRHE for 120 h with no notable decay in photocurrent density [Fig. 7f]. The ABPE value of G-Ni3SxO2–x/p-Si was calculated to be 3.9%, which is nine times that of Ni3S2/Si (0.4%) [Fig. 7g]. Along with the suitable band positions of G-Ni3SxO2–x with p-Si [Fig. 7h], the Mott-Schottky plots revealed an enhanced charge carrier concentration and onset potential of G-Ni3SxO2–x/p-Si compared to those of Ni3S2/p-Si [Fig. 7i].

a Schematic illustration of NiSe2 decorated over a SiNW array. b SEM and HRTEM images of the SiNW array deposited with NiSe2 NCs (NS-1). c LSV curves of bare p-SiNW and NS photocathodes. d LSV curves of bare n-SiNW and NS-1 as photoanodes measured in the 1 M KOH electrolyte. Reproduced with permission from ref. 64. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. e Schematic representation of the novel G-Ni3SxO2−x integrated p-Si photocathode for enhanced solar hydrogen production in alkaline media. f PEC LSV curves and g ABPE of the p-Si, Ni3S2/p-Si, and G-Ni3SxO2−x/p-Si photocathodes in 1 M NaOH solution. h Comparison of the energy level diagrams and (i) Mott-Schottky plots of p-Si, Ni3S2, and G-Ni3SxO2−x. Reproduced with permission from ref. 72. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH.

Emerging cocatalysts for the PEC-OER

The OER occurs at the photoanode surface using photogenerated holes (minority charge carriers). Usually, photoanodes are reported in neutral or basic electrolyte media. Despite several advances in n-type semiconductors, charge recombination and photocorrosion have been major obstacles, resulting in low efficiency and stability. Typically, water oxidation catalysts (WOCs) attract holes and involve four sequential proton-coupled electron transfers that allow oxygen‒oxygen bond formation and ensure the stable development of PEC cells. Transition metal (Co, Ni, Fe)-based oxide/hydroxides are the most common and stable cocatalysts known to enhance activity and OER kinetics and promote stability comparable to benchmark noble metal cocatalysts such as IrOx and RuOx because of their excellent metallic electronic conductivity73. Transition metal sulfides, nitrides, and phosphide are also known to be OER catalysts but are less thermodynamically stable in terms of their oxidizing potentials. These cocatalysts easily oxidize to the metal oxide/hydroxide in aqueous and strongly oxidizing environments of the OER74. However, noble metal cocatalysts have drawbacks. For instance, RuO2 is susceptible to corrosion under alkaline conditions, whereas IrO2 suffers from poor conductivity. Furthermore, the most negligible aspect of their usage is their high cost and extremely low abundance. Thus, it is imperative to develop highly stable, active, and low-cost cocatalysts as alternatives to precious noble metal-based cocatalysts. Transition metal-based cocatalysts could fill this role and replace noble metal cocatalysts for the OER.

The activity of cocatalysts depends on various parameters, such as size, morphology, thickness, optical transparency, active sites on the surface, crystal structure, and surface area of the cocatalyst. The variable sizes of NPs in the cocatalyst will have different surface areas, which leads to different activities for the OER on the surface of a photoanode. The smaller the size of the NPs is, the better the charge extraction at the interface of the semiconductor and cocatalyst. For instance, Co3O4 cocatalysts showed size-dependent as well as surface area-dependent properties for their activity over different LaTiO2N photocatalysts with different morphologies75. The activity of the cocatalyst can be a function of the interlayer anion. The activity of the nickel-iron-layered double hydroxide (NiFe-LDH) cocatalyst was observed to vary upon changing the interlayer anion76. Modification of the electrochemically active surface area rather than the intrinsic composition of the cocatalyst can enhance OER activity77. The morphology of the cocatalyst is another factor that governs the activity of the cocatalyst and the kinetics of the reaction78. Devices that are in tandem where the light needs to be transmitted require a transparent cocatalyst to minimize the optical loss on the photoactive material of the photoanode79. Parasitic light absorption over the photoanode surface leads to low photon-to-current conversion efficiency. NixCo1–xOy-based optically transparent ultrathin films have shown higher electrocatalytic activity than the benchmark IrO280.

Co-based cocatalysts

Cobalt-based catalysts are also known to catalyze OER reactions. Complexes such as cobalt oxides (Co3O4 and CoOx), phosphides (Co-Pi), and boride (Co-Bi) catalysts can be synthesized by various methods (such as electrodeposition, photoassisted deposition, hydrothermal methods, ALD, etc.) and have been widely studied58. Co-based catalysts generated by facile syntheses have shown high OER activity in an alkaline medium.

Metal-organic framework (MOF)-derived Co3O4-modified TiO2 nanorod arrays were grown over an n-Si substrate (MOF Co3O4/TiO2/Si NR ternary heterojunction photoanode for water splitting [Fig. 8a]81. The introduction of TiO2 on Si results in an abnormal type-II heterojunction that efficiently separates electron and hole pairs. The CB and VB of Si are higher than those of TiO2. The photogenerated holes of Si and electrons of TiO2 recombine, giving efficient separation of the photogenerated electrons in n-Si and holes in TiO2 with better charge injection efficiency [Fig. 8b]. The decoration of MOF-derived Co3O4 NSs enlarged the surface area and increased the kinetics of water oxidation. Typical results inferred that Co3O4/TiO2/Si NR photoelectrodes achieved a high photoconversion efficiency (0.54% at 1.04 VRHE) due to the synergistic effect of MOF-derived Co3O4 and abnormal type-II heterojunctions in the Co3O4/TiO2/Si NR composite. Moreover, the Co3O4/TiO2/Si NR electrode delivered photocurrent densities of 2.71 and 1.78 mA cm−2 at 1.23 VRHE [Fig. 8c] with superior stability over 2 h in alkaline and neutral media, along with an improved IPCE [Fig. 8d]. BiVO4 (BVO) has been a promising candidate for PEC water oxidation. However, it suffers from poor carrier mobility and surface recombination. The larger radius of V4+ in BVO acts as a scattering center and reduces the diffusion length of the holes82. It is therefore very challenging to control and tune the V4+ content, although electrochemical treatment has effectively generated defects in metal oxides, enhancing the photoactivity. Creating an oxygen vacancy (Ov) as an intrinsic defect has been shown to improve charge separation efficiency83. Electrochemical treatment of (040) faceted grown films of BVO over F:SnO2 enhanced the photocurrent density by 10-fold at 1.23 VRHE14. The Co-Bi cocatalyst was loaded over BVO films via photo-assisted electrodeposition. The enhanced PEC performance was attributed to the partial reduction of Bi3+ and V5+ ions in BVO, generating oxygen vacancies and suppressing bulk and surface recombination. Additionally, Co-Bi loading promoted both the charge transfer kinetics and good stability for photoconversion efficiency.

a Relative band positions of Co3O4/TiO2/Si and Co3O4/TiO2/FTO. b Schematic illustration of the MOF-derived Co3O4/TiO2/Si NR array synthesis protocol. c LSV curves of photoanodes in 1 M NaOH. d IPCE curves of the TiO2/FTO, TiO2/Si, Co3O4/TiO2/FTO, and Co3O4/TiO2/Si photoanodes. Reproduced with permission from ref. 81. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH.

Double-layer cocatalysts for the modification of BiVO4 photoanodes through surface passivation for OERs have shown improved stability and PCE15. BiVO4/NiFeOOH/Co-Pi core-shell structures fabricated with NiFeOOH (a hole transporting layer) capture the charge generated in BiVO4 and transfer the holes from the NiFeOOH layer to Co-Pi [Fig. 9a]. BiVO4/NiFeOOH/Co-Pi core-shell structures delivered a high photocurrent (2.03 mA cm−2 at 1.23l VRHE), a lower onset potential (0.031 VRHE), and a high IPCE (%) compared to the pure BiVO4 photoanode [Fig. 9b, c]. The BiVO4/Co-Pi, BiVO4/NiFeOOH, and BiVO4 photoanodes were compared with BiVO4/NiFeOOH/Co-Pi, and the enhanced PEC performance was attributed to the synergistic effect of the NiFeOOH/Co-Pi cocatalyst. Single-atom catalysis (SAC) was first introduced in 2011 by Liu and coworkers and describes the high Co oxidation activity of a single Pt atom dispersed on FeOx. Recently, Co single-atom-nanocrystal deposition over (040) faceted BiVO4 was reported [Fig. 9d]84. At 1.23 VRHE, the as-prepared BiVO4(040)/Co SAs-NC photoanode generated 2.2 times more photocurrent density than pure BiVO4(040) and had nearly 100% charge injection efficiency [Fig. 9e]. The ABPE (%), charge separation efficiency (%), and charge injection efficiency (%) of BiVO4(040)/Co SAs-NCs were much more significant than those of pure BiVO4(040) [Fig. 9e–h].

a Schematic illustration of the bandgap energy diagram of BiVO4/NiFeOOH/Co-Pi. b LSV curves and c IPCE (%) of the BiVO4, BiVO4/Co-Pi, BiVO4/NiFeOOH, and BiVO4/NiFeOOH/Co-Pi photoanodes. Reproduced with permission from ref. 15. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. d Schematic illustration of the fabrication of BiVO4(040)/Co SAs-NC over FTO. e LSV curves, f ABPE (%), g charge separation (%), and h charge injection (%) of the BiVO4(040), BiVO4(040)/Co NPs-NC, and BiVO4(040)/Co SAs-NC photoanodes. Reproduced with permission from ref. 84. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Hematite (Fe2O3), as a photoabsorber material, suffers from two problems: poor charge separation, and the slow water splitting oxidation kinetics, but the deposition of cocatalysts has been proven to enhance the kinetics and stability. This can be shown with the p-n heterojunction of p-Co3O4/n-Fe2O3 with deposition of a cocatalyst (Co-Pi) owing to the high catalytic behavior of Co3O4 for the oxygen evolution reaction as well as the induced interfacial electric field that facilitates the separation and transportation of charge carriers85. As a result, the superior photocurrent density of the Co-Pi/Co3O4/Ti:Fe2O3 photoanode was 2.7 mA cm−2 at 1.23 VRHE, which is 125% greater than that of the Ti:Fe2O3 photoanode. On Co-Pi/Co3O4/Ti:Fe2O3, the optimum charge injection and bulk separation efficiency (ηinj and ηsep) were 91.6 and 23.0% at 1.23 VRHE, respectively. Decoration of Ni-Co3O4 effectively boosted the water oxidation kinetics with BiVO4. The Ni doping-induced enhancement in the photoconductivity and surface kinetics of BiVO4-Ni/Co3O4 (2.23 mA cm−2 at 1.23 VRHE) led to enhancements in ηinj and ηsep31.

Ni-based cocatalysts

In the visible area, NiOx is optically transparent because of its bandgap (Eg = 3.7 eV), and its index of refraction makes it close to ideal for use as an antireflective coating on various semiconductor surfaces70. NiOx is chemically stable at high pH and creates a catalytic surface layer for the oxygen evolution process. The interfacial layers between the semiconductor and cocatalyst also play a significant role in PEC performance. In a study with NiOx, an ultrathin (2 nm) film of CoOx was used over an n-Si photoanode. The coating of a multifunctional NiOx layer created by sputter deposition increased the OCV, band bending at the interface, and onset potential of n-Si/SiOx,RCA/CoOx/NiOx compared to n-Si/SiOx,RCA/NiOx. The PEC performance shown by the n-Si/SiOx,RCA/CoOx/NiOx device in 1 M KOH held at 1.63 VRHE yielded a remarkable photocurrent density of 30 ± 2 mA cm−2 for 1700 h86. Ni/NiOx core-shell structured NPs as cocatalysts were synthesized on top of an n-Si photoanode via pulsed electrodeposition [Fig. 10a]65. The optimal amount of NiOx/Ni NPs over n-Si yielded 100% quantum efficiency and recorded a photocurrent density of 14.7 mA cm−2 at 1.23 VRHE in 1 M NaOH [Fig. 10b]. After annealing, the cocatalyst showed enhanced PEC performance [Fig. 10c, d]. The saturated current density decreased as the excess Ni NPs deposited, and the onset potential moved in the anodic direction [Fig. 10c, d].

a Schematic illustration of the n-Si/Ni/NiOx photoanode and charge transfer mechanism. b LSV curves of Ni/n-Si and NiOx/Ni/n-Si after different numbers of cycles of pulsed electrodeposition. c Comparison of onset potential versus the number of deposition cycles of the Ni/n-Si photoanode. d Current density versus the number of deposition cycles of the Ni/n-Si photoanode. e LSV curves of the NiOx/Ni/n-Si heterojunction photoanodes. f IPCE (%) versus the number of deposition cycles. Reproduced with permission from ref. 65. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) are known to improve the light response of photoelectrodes with high photocurrent density at relatively low OCP and feasible charge separation. Despite these advantages, the water-splitting efficiency of CQDs is low. NiOOH/FeOOH WOC shells integrated with the CQD/BiVO4 photoanode NiOOH/FeOOH/CQD/BiVO4 (NFCB) generated charge carriers from BiVO4 and CQDs and transferred them to the NiOOH/FeOOH hybrid WOC for the OER22. Under AM 1.5 G in KH2PO4 aqueous solution (pH = 7), the NFCB photoanode produced remarkable photocurrent densities of 3.91 and 5.99 mA cm−2 at 0.6 and 1.23 VRHE, respectively. CQDs also played a significant role in transferring holes from BiVO4 to NiOOH/FeOOH.

The crucial role of cocatalysts is well accepted among researchers, but much less attention has been given to optimizing their electronic structures to further enhance their PEC performance and stability. Partial substitution of the O sites with a less electronegative atom in metal oxide catalysts is an effective strategy to modify cocatalysts, enhancing electron transfer and suppressing recombination87. Notably, rational tailoring of the electronic structure in Ni-doped FeOx (Ni:FeOx) by partially substituting the O sites with less electronegative N atoms and integration with BiVO4 was carried out to examine the N:NiFeOx/BiVO4 photoanode88. The incorporation of N led to electron enrichment at the Ni and Fe sites in NiFeOx, which led to fast electron transfer from Ni to lattice V in BiVO4, while the Fe sites attracted holes to promote OER kinetics. XPS studies confirmed the formation of V(5–x)+. DFT calculations confirmed the electron density enrichment at the Ni and Fe sites after incorporating the N atom. The N:NiFeOx/BiVO4 photoanode delivered 6.4 mA cm−2 at 1.23 VRHE in 0.3 M K3BO3 (pH = 9.5) under AM 1.5 G simulated light with remarkable stability for 5 h and no decrease in photocurrent density. The doping of Ni in iron phosphide WOCs also improved the electronic structure and reaction kinetics. LDHs have also been intensively studied as cocatalysts for the OER. NiFe-LDH is one of the LDHs being used as a cocatalyst for the OER in PEC applications. Recently, the yttrium-induced regulated electron density in NiFe-LDH was studied by decorating over BiVO489. The NiFeY-LDH reduced the interfacial recombination of the BiVO4/cocatalyst and inhibited the photocorrosion of BiVO4. The BiVO4/NiFeY-LDH photoanode achieved a photocurrent density of 5.2 mA cm−2 at 1.23 VRHE under AM 1.5 G illumination [Fig. 11a]. Notably, the photoanode showed outstanding stability at 0.8 VRHE over 25 h. The IPCE (%) [Fig. 11b] and Nyquist plots [Fig. 11c] hinted toward efficient conversion efficiency and the lowest RCT value of the NiFeY-LDH/BiVO4 photoanode. Calculations using DFT show that incorporating Y into Ni sites caused rapid charge transfer between Ni and Fe by allowing local charge transfer. This, in turn, can influence the electronic environment of NiFe-LDH and raise the electron-hole transport rate to the interface. Recently, electroless plating of a high-performance NiFeP alloy WOC over a micropyramid-textured n-Si photoanode was performed [Fig. 11e]32. The autocatalytic electroless plating of the NiFeP WOC over n-Si involved the absorption of SnII on the n-Si surface followed by the replacement of Pd0 ions, which acted as a reaction initiator. The photoelectrode with Pd0 on the surface was dipped in a plating solution containing Ni, Fe, and P precursors for 40 s. An island-like NiFeP alloy covering the n-Si surface with a 3D structure with a high specific surface area was formed [Fig. 11f]. NiFeP/n-Si showed a saturated photocurrent of ~40 mA cm−2, and 15.5 mA cm−2 was achieved at 1.23 VRHE, which decayed until 9 mA cm−2 after 17 h of continuous illumination in 1 M KOH [Fig. 11g], while in the KBi electrolyte, NiFeP/n-Si showed stability up to 75 h with no decay in photocurrent density [Fig. 11h]. The decreased PEC activity was due to n-Si photocorrosion.

a LSV plot, b IPCE (%), and c Nyquist plots of BiVO4, NiFe-LDH/BiVO4, and NiFeY-LDH/BiVO4. Reproduced with permission from ref. 89. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. d Schematic illustration of the fabrication process of the electroless plating of NiFeP over the n-Si substrate. e FE-SEM images of the Si electrodes deposited with NiFeP for 10 s, 20 s, 40 s, and 60 s. Chronoamperometric curve of the NiFeP/n-Si photoanode under light irradiation at 1.23 VRHE in f 1.0 M KOH and g 1.0 M KBi (pH 9.2). h The chronoamperometric curve of the NiFeP(20 s)/n-Si photoanode under light irradiation at 1.23 VRHE in 1.0 M KOH. Reproduced with permission from ref. 32. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

Fe-based cocatalysts

Fe-based OER catalysts are capable of evolving O2 at moderate overpotentials. Catalysts such as FeOx23, FeOOH90, and Fe phosphides32 have been studied and applied over photoanodes due to their low-cost, easy synthesis, and coating techniques in addition to their excellent stability and superior catalytic activity for the OER. A commercially available Fe-based polymer, PVF (poly(vinyl ferrocene)), the precursor of FeOx, was coated on electrodeposited BiVO4 films23. Annealing PVF in air resulted in the formation of FeOx, forming an FeOx/BiVO4 structure, which resulted in a decrease in Eop, increased reaction kinetics and a 92% transfer efficiency at 1.23 VRHE and was stable for up to 3 h with no decrease in photocurrent density in KBi (pH = 9.6) electrolyte.

With progress in the development of WOCs, the deposition techniques of FeOOH remain limited, such as electrodeposition or photodeposition, and both techniques are sensitive to the morphology of the photoabsorber material91,92. Coating FeOOH using electro- and photodeposits might not be uniform over heterogeneous and anisotropic structures. A one-step hydrothermal reaction was reported that uniformly deposited Ni-doped FeOOH NPs over WO3/BiVO4 core-shell NWs and several other photoactive materials, such as BiVO4 films, WO3 NWs, α-Fe2O3 NWs, TiO2 NWs, and planar Si wafers [Fig. 12a]93. In this study, a Ni:FeOOH (5–10 nm)-coated WO3/BiVO4 core/shell NW photoanode with strong adhesion and little parasitic absorption imparted good stability to the photoanode under illumination. The Ni:FeOOH/WO3/BiVO4 core/shell NW photoanode delivered 4.5 mA cm−2 [Fig. 12b] and a remarkable 91% charge transfer efficiency at 1.23 VRHE under AM 1.5 G [Fig. 12c]. In another report, fluorine-doped FeOOH over a BiVO4 photoanode via a hydrothermal process was compared with a FeOOH/BiVO4 photoanode [Fig. 12d, f]90. The p-n heterojunction of the F:FeOOH/BiVO4 photoanode showed a remarkable photocurrent of 2.6 mA cm−2 at 1.23 VRHE [Fig. 12e]. Very recently, a study of versatile coupling to engineer atomically dispersed M-N4 sites (M = Ni, Co, and Fe) coordinated with an axial direction oxygen atom (M-N4-O) incorporated between FeOOH, WOC, and BiVO4 was reported [Fig. 12g]94. This cutting-edge FeOOH/Ni-N4-O/BiVO4 photoanode achieved a high photocurrent density of 6.0 mA cm−2 at 1.23 V versus RHE, which is 3.97 times higher than that of BiVO4 [Fig. 12h], resulting in remarkable long-term photostability of up to 200 h. The IPCE of the FeOOH/Ni-N4-O/BiVO4 photoanode was approximately two times higher than that of pristine BiVO4 [Fig. 12i]. Ni-N4-O/BiVO4 achieved a photocurrent density 2.65 times higher than that of BiVO4, and it was inferred that Ni-N4-O acted as a bridge between BiVO4 and FeOOH and helped in the fast transfer of photogenerated holes.

a Schematic illustration with FE-SEM images of WO3/BiVO4 NWs and Ni:FeOOH-coated WO3/BiVO4 NWs. b LSV curves of WO3/BiVO4 in H2O2 and WO3/BiVO4/NiFeOOH and WO3/BiVO4 in H2O. c Charge transfer efficiencies (%) of WO3/BiVO4 and WO3/BiVO4/NiFeOOH. Reproduced with permission from ref. 93. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. LSV curves d under chopped AM 1.5 G and e continuous AM 1.5 G illumination of BiVO4, FeOOH/BiVO4, and F:FeOOH/BiVO4. f Synthesis and deposition protocol of F:FeOOH over BiVO4. Reproduced with permission from ref. 90. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. g Schematic illustration of the synthesis procedure for the FeOOH/Ni-N4-O/BiVO4 array. h LSV curves and i IPCE (%) of BiVO4, NiOOH/Ni-N4-O/BiVO4, and FeOOH/Ni-N4-O/BiVO4 photoanodes. Reproduced with permission from ref. 94. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society.

Conclusions, remarks, and future perspectives

PEC water splitting is the most promising technique for producing hydrogen and oxygen. However, several limitations and challenges, such as photocorrosion, recombination, catalyst instability, and low STH efficiency, limit its industrial applications. With the literature flooded with new reports, it has become crucial to summarize them in the form of a review. Herein, we summarized the mechanism by which the loading of cocatalysts can enhance PEC performance and efficiency and reviewed recent advances in earth-abundant heterogeneous cocatalysts using reports of PEC water splitting. The efficiency, specificity, and longevity of PEC photoelectrodes have all been greatly improved using cocatalysts. Additionally, we added reports of bifunctional catalysts that serve to enhance both the HER and OER.

Kinetics-controlled PEC water splitting improves significantly in the presence of catalyst materials with specificity for the HER and OER. Charge carrier generation, separation, and migration are critically important factors governing the fate of the efficiency of a particular PEC system16. The strategy to implement a cocatalyst offers additional and pivotal advantages compared to the photoelectrodes without cocatalysts. The crucial roles of cocatalysts are as follows.

-

i.

Cocatalysts provide a surface with specific surface-active sites responsible for reduction and oxidation.

-

ii.

Cocatalysts selectively trap, separate photogenerated charge carriers, and suppressing recombination.

-

iii.

Band bending in semiconductors in the presence of cocatalysts facilitates excited-state charge transfer.

-

iv.

Passivation layers protect the photoactive layer from photocorrosion.

-

v.

The Eop values for the HER and OER tend to increase and decrease, respectively.

-

vi.

Most importantly, the kinetics of the HER and OER without WRCs and WOCs will be very slow on the semiconductor surface, while in their presence, the rates of the HER and OER have been proven to be enhanced by a remarkable amount.

Mo-sulfides, Co-phosphides, and NiS are well-known PEC-HER cocatalysts due to their catalytic activity that is comparable with that of Pt-based catalysts. PEC-OER cocatalysts such as Ni:FeOOH, Co3O4, and NiOOH are extensively used due to their catalytic activity comparable to those of Ru- and Ir-based catalysts. Modification of the electronic structure by vacancy defects and doping procedures demonstrates the possibility for the synthesis of robust bifunctional cocatalysts for the HER and OER. Cocatalysts are typically coated over semiconductor films using thin-film deposition techniques such as photo/electrodeposition, spray coating, CVD, etc., but after the continuous operation of PEC cells, the cocatalyst is removed from the surface due to nonuniformity or destabilization leading to photocorrosion. To solve this problem, it is necessary to investigate more efficient ways to integrate surface modification approaches that can transfer charge carriers quickly while preventing electrolyte contact with the photoactive layer.

Although HER and OER cocatalysts improve PEC performance and efficiency, it is impossible to fabricate high-efficiency, robust and stable PEC cells by only loading cocatalysts on the surface. Engineering the interface between the cocatalyst and the surface of the photoelectrode is of utmost importance to facilitate the reaction. Strategies include incorporating interlayers between the semiconductor film and cocatalyst or adding passivation layers, selective hole transporting layers (HTLs), hole-storage layers, electron transporting layers, and electron-blocking layers that can be employed with efficient cocatalysts to improve the photoelectrode PEC performance. Moreover, few reports on the comparative and combined experimental and theoretical (computational) study of the crystal structure and reaction mechanism involved over the catalyst surface are known. The cocatalyst/electrolyte interface should be studied in detail in different electrolytes, which can affect surface reactions. New methods of controlled doping must be explored to improve the surface area and active sites of the cocatalysts. The core-shell structures of cocatalysts with multijunction components must be given more importance and studied in greater detail, which can give a synergistic effect by separating charge carriers and suppressing recombination.

Along with the preferences mentioned above for cocatalysts, semiconductors with narrow bandgaps and high charge carrier concentrations that exhibit high stability in an aqueous medium must be explored. The favorable band positions of heterojunctions with enhanced charge separation efficiency and transfer efficiency must be integrated with the HTLs, interlayers, and cocatalyst configurations. Studies will focus on understanding, characterizing, and developing new and modified efficient cocatalysts with superior activity and stability.

References

Staffell, I. et al. The role of hydrogen and fuel cells in the global energy system. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 463–491 (2019).

Rajeshwar, K. Solar energy conversion and environmental remediation using. J. Phys. Chem. 2, 1301–1309 (2011).

Fujishima, A. & Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238, 37–38 (1972).

Su, J. & Vayssieres, L. A place in the sun for artificial photosynthesis? ACS Energy Lett. 1, 121–135 (2016).

Subramanyam, P., Meena, B., Biju, V., Misawa, H. & Challapalli, S. Emerging materials for plasmon-assisted photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. Photochem. Rev. 51, 100472 (2022).

Chaves, A. et al. Bandgap engineering of two-dimensional semiconductor materials. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 4, 29 (2020).

Tay, Y. F. et al. Solution-processed Cd-substituted CZTS photocathode for efficient solar hydrogen evolution from neutral. Water Joule 2, 537–548 (2018).

Kwon, K. C. et al. Wafer-scale transferable molybdenum disulfide thin-film catalysts for photoelectrochemical hydrogen production. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 2240–2248 (2016).

Meena, B. et al. Rational design of TiO2/BiSbS3 heterojunction for efficient solar water splitting. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 49, 101775 (2022).

Kumar, M., Ghosh, C. C., Meena, B., Ma, T. & Subrahmanyam, C. Plasmonic Au nanoparticle sandwiched CuBi2O4/Sb2S3 photocathode with multi-mediated electron transfer for efficient solar water splitting. Sustain. Energy Fuels 6, 3961–3974 (2022).

Subramanyam, P., Meena, B., Suryakala, D., Deepa, M. & Subrahmanyam, C. Plasmonic nanometal decorated photoanodes for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Catal. Today 379, 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2020.01.041 (2020)

Chen, D. & Liu, Z. Efficient indium sulfide photoelectrode with crystal phase and morphology control for high-performance photoelectrochemical water splitting. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 12328–12336 (2018).

Jun, S. E. et al. Boosting unassisted alkaline solar water splitting using silicon photocathode with TiO2 nanorods decorated by edge-rich MoS2 nanoplates. Small 17, 1–10 (2021).

Wang, S., Chen, P., Yun, J. H., Hu, Y. & Wang, L. An electrochemically treated BiVO4 photoanode for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8500–8504 (2017).

Fang, G., Liu, Z. & Han, C. Enhancing the PEC water splitting performance of BiVO4 co-modifying with NiFeOOH and Co-Pi double layer cocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 515, 146095 (2020).

Yang, J., Wang, D., Han, H. & Li, C. Roles of cocatalysts in photocatalysis and photoelectrocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1900–1909 (2013).

Nandjou, F. & Haussener, S. Kinetic competition between water-splitting and photocorrosion reactions in photoelectrochemical devices. ChemSusChem 12, 1984–1994 (2019).

Ding, C., Shi, J., Wang, Z. & Li, C. Photoelectrocatalytic water splitting: significance of cocatalysts, electrolyte, and interfaces. ACS Catal. 7, 675–688 (2016).

Ma, P. & Wang, D. The principle of photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nanomater. Energy Convers. Storage 1–61. https://doi.org/10.1142/9781786343635_0001 (2017)

Walter, M. G. et al. Solar water splitting cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6446–6473 (2010).

Liu, Z., Lu, X. & Chen, D. Photoelectrochemical water splitting of CuInS2 photocathode collaborative modified with separated catalysts based on efficient photogenerated electron-hole separation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 10289–10294 (2018).

Ye, K. H. et al. Carbon quantum dots as a visible light sensitizer to significantly increase the solar water splitting performance of bismuth vanadate photoanodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 772–779 (2017).

Saada, H. et al. Boosting the performance of BiVO 4 prepared through alkaline electrodeposition with an amorphous Fe Co-catalyst. ChemElectroChem 6, 613–617 (2019).

Li, S. et al. A synergetic strategy to construct anti-reflective and anti-corrosive Co-P/WSx/Si photocathode for durable hydrogen evolution in alkaline condition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 304, 120954 (2022).

Yu, Y. et al. High phase-purity 1T′-MoS2- and 1T′-MoSe2-layered crystals. Nat. Chem. 10, 638–643 (2018).

Ji, Y. et al. Bifunctional o-CoSe2/c-CoSe2/MoSe2 heterostructures for enhanced electrocatalytic and photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Today Chem. 23, 100724 (2022).

Wan, X., Su, J. & Guo, L. Enhanced photoelectrochemical water oxidation on BiVO4 with mesoporous cobalt nitride sheets as oxygen-evolution cocatalysts. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2557–2563 (2018).

Morales-Guio, C. G. et al. Solar hydrogen production by amorphous silicon photocathodes coated with a magnetron sputter deposited Mo2C catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7035–7038 (2015).

Masa, J. et al. Amorphous cobalt boride (Co 2 B) as a highly efficient nonprecious catalyst for electrochemical water splitting: oxygen and hydrogen evolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1–10 (2016).

Dolai, S. et al. Exfoliated molybdenum disulfide-wrapped CdS nanoparticles as a nano-heterojunction for photo-electrochemical water splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 438–448 (2021).

Bai, H. et al. Fabrication of BiVO4-Ni/Co3O4 photoanode for enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 538, 148150 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Electroless plating of NiFeP alloy on the surface of silicon photoanode for efficient photoelectrochemical water oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 11479–11488 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Engineering heterogeneous semiconductors for solar water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 2485–2534 (2015).

Taylor, P., Kepler, R. G. & Anderson, R. A. Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences Piezoelectricity in polymers. (2006).

Ding, C., Shi, J., Wang, Z. & Li, C. Photoelectrocatalytic water splitting: significance of cocatalysts, electrolyte, and interfaces. ACS Catal. 7, 675–688 (2017).

Zhang, Z. & Yates, J. T. Band bending in semiconductors: chemical and physical consequences at surfaces and interfaces. Chem. Rev. 112, 5520–5551 (2012).

Polman, A. & Atwater, H. A. Photonic design principles for ultrahigh-efficiency photovoltaics. Nat. Mater. 11, 174–177 (2012).

Hisatomi, T., Kubota, J. & Domen, K. Recent advances in semiconductors for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 7520–7535 (2014).

Yang, W., Prabhakar, R. R., Tan, J., Tilley, S. D. & Moon, J. Strategies for enhancing the photocurrent, photovoltage, and stability of photoelectrodes for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 4979–5015 (2019).

Jang, Y. J. & Lee, J. S. Photoelectrochemical water splitting with p-type metal oxide semiconductor photocathodes. ChemSusChem 12, 1835–1845 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Progress in developing metal oxide nanomaterials for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1–26 (2017).

Jiang, P. et al. CoP nanostructures with different morphologies: synthesis, characterization and a study of their electrocatalytic performance toward the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 14634 (2014).

Wu, L. et al. The origin of high activity of amorphous MoS2 in the hydrogen evolution reaction. ChemSusChem 12, 4383–4389 (2019).

Morales-Guio, C. G. et al. Solar hydrogen production by amorphous silicon photocathodes coated with a magnetron sputter deposited Mo2C catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7035–7038 (2015).

Huang, S. et al. Synergistically modulating electronic structure of NiS2 hierarchical architectures by phosphorus doping and sulfur-vacancies defect engineering enables efficient electrocatalytic water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 420, 127630 (2021).

Zhang, F. et al. Coupling Ru-MoS2 heterostructure with silicon for efficient photoelectrocatalytic water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 423, (2021).

Kang, M. A. et al. Fabrication of flexible optoelectronic devices based on MoS2/graphene hybrid patterns by a soft lithographic patterning method. Carbon N. Y. 116, 167–173 (2017).

Zhang, D., Sun, Y., Li, P. & Zhang, Y. Facile fabrication of MoS2-modified SnO2 hybrid nanocomposite for ultrasensitive humidity sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 14142–14149 (2016).

Sarkar, D. et al. Expanding interlayer spacing in MoS2 for realizing an advanced supercapacitor. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 1602–1609 (2019).

Mom, R. V., Louwen, J. N., Frenken, J. W. M. & Groot, I. M. N. In situ observations of an active MoS2 model hydrodesulfurization catalyst. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–8 (2019).

Hinnemann, B. et al. Biomimetic hydrogen evolution: MoS2 nanoparticles as catalyst for hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 5308–5309 (2005).

Zhang, S. et al. A hierarchical SiPN/CN/MoSx photocathode with low internal resistance and strong light-absorption for solar hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 300, 120758 (2022).

Hasani, A. et al. Direct synthesis of two-dimensional MoS2 on p-type Si and application to solar hydrogen production. NPG Asia Mater. 11, (2019).

Jiang, Z. et al. MoS2 Moiré superlattice for hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Energy Lett. 2830–2835 https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.9b02023 (2019)

Ding, Q. et al. Designing efficient solar-driven hydrogen evolution photocathodes using semitransparent MoQ x Cl y (Q = S, Se) catalysts on Si micropyramids. Adv. Mater. 27, 6511–6518 (2015).

Roy, K., Maitra, S., Ghosh, D., Kumar, P. & Devi, P. 2D-Heterostructure assisted activation of MoS2 basal plane for enhanced photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 435, 134963 (2022).

Choi, H. et al. An organometal halide perovskite photocathode integrated with a MoS 2 catalyst for efficient and stable photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 22291–22300 (2021).

Soni, V. et al. Advances and recent trends in cobalt-based cocatalysts for solar-to-fuel conversion. Appl. Mater. Today 24, 101074 (2021).

Thalluri, S. M. et al. Inverted pyramid textured p-silicon covered with Co2P as an efficient and stable solar hydrogen evolution photocathode. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 1755–1762 (2019).

Kempler, P. A., Gonzalez, M. A., Papadantonakis, K. M. & Lewis, N. S. Hydrogen evolution with minimal parasitic light absorption by dense Co–P catalyst films on structured p-Si photocathodes. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 612–617 (2018).

Sun, X., Liu, C., Zhang, P., Gong, L. & Wang, M. Interface-engineered silicon photocathodes with a NiCoP catalyst-modified TiO2 nanorod array outlayer for photoelectrochemical hydrogen production in alkaline solution. J. Power Sources 484, 229272 (2021).

Chen, D., Liu, Z., Guo, Z., Yan, W. & Ruan, M. Decorating Cu2O photocathode with noble-metal-free Al and NiS cocatalysts for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting by light harvesting management and charge separation design. Chem. Eng. J. 381, 122655 (2020).