Abstract

Fluorescent molecules and materials are widely used in many areas in physics, chemistry, and biology as emitters, tags, or sensors. The possibility of controlling their fluorescence signal by light, namely, fluorescence photoswitching, down to the nanoscale level can then dramatically extend their fields of applications. This review focuses on fluorescent and photochromic diarylethene-based nanosystems. The choice of the diarylethene family has been driven by its excellent photoswitching properties (conversion yield, bistability, fatigue resistance), which make them fully appropriate when high-performance behavior is required. The different molecular and nanomaterial designs providing suitable combinations of fluorescence and photochromism are summarized. Besides the inherently fluorescent diarylethene molecules, chemical association between photochromic and fluorescent molecular units can advantageously lead to fluorescence photoswitching thanks to resonance energy transfer or intramolecular electron transfer processes. Furthermore, the preparation of nanoscale emissive materials involving diarylethene units paves the way to new interesting features, such as near-infrared control of emissive and photoswitchable nanohybrids, giant amplification of the fluorescence photoswitching in organic nanoparticles, or fluorescence color modulation. Many applications derived from such fluorescent diarylethene-based molecules and nanomaterials have been developed recently, especially in the field of biology for fluorescence biolabeling and super-resolution imaging but also for photocontrol of biological functions. Extremely promising prospects are expected in the near future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Molecules that can reversibly change in response to external stimuli are of central importance not only to the development of molecular devices and memory materials but also to pharmacology and imaging technologies1,2,3,4,5. Organic photochromic compounds6,7, which reversibly change color under excitation with an appropriate wavelength of light, are good examples of such molecular systems. The difference in geometry and electronic structure between the two isomers can be exploited to reversibly control a wide variety of properties. In particular, photoswitching of fluorescence signals has attracted much attention because of its potential in various optoelectronic applications, including optical memories, bioimaging, and photoswitches with high sensitivity8,9,10,11. In addition, the recent progress of fluorescence-based imaging technology including super-resolution microscopy5,10,12,13, which can achieve higher spatial resolution beyond the diffraction limit of light, further encourages the development of fluorescence photoswitchable molecules. Therefore, the improvement of the fluorescence photoswitching performances of such molecules is quite a hot topic in various research fields, and many excellent molecular systems have been actively designed up to now.

Among different classes of photochromic compounds, such as azobenzenes, spiropyranes, hexaarylbiimidazoles, and diarylethenes (DAEs), DAE derivatives (Fig. 1) have attracted particular attention in recent years because of their high fatigue resistance and excellent thermal stability. DAE derivatives can be switched between open- and closed-ring isomers upon irradiation with appropriate wavelengths of light >104 times, and the photogenerated closed-ring isomers are estimated to be stable for >1000 years at 30 °C14,15. Therefore, DAEs are promising candidates for applications not only in optical data storage as well as molecular switches but also as biomarkers to probe biological events14,15,16,17.

In this review, we will focus on the recent progress of fluorescent photoswitchable nanosystems composed of DAE derivatives, where the nanosystem involves single molecules, nanoparticles (NPs), molecular-assembling systems, and organic/inorganic hybrid materials.

Molecular systems combining fluorescence and photochromism can be classified into the following three categories:

-

Type 1: Inherently fluorescent photoswitchable molecules, which exhibit both fluorescence and photochromism.

-

Type 2: Molecular systems consisting of fluorescent and photochromic moieties that are linked with each other via covalent bonds. Fluorescence can be reversibly modulated by the photochromic moiety through intramolecular interaction, such as energy transfer or electron transfer.

-

Type 3: Hybrid materials composed of fluorescent molecules and photochromic molecules, for example, doped in a polymer matrix, grafted on the surface of NPs, or gathered as NPs. Again, fluorescence can be reversibly modulated by the photochromic moiety through intermolecular interaction.

In the following, recent progress reports of representative fluorescent photoswitchable DAE systems in each category and their applications at the nanoscale have been reviewed. For the sake of clarity, this review article will not include all accomplishments related to this research field, and therefore the most important and recent developments will be described by selecting a few representative examples. Many other excellent review papers reported previously will help to cover the wide variety of results reported so far8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

Inherently fluorescent photoswitchable DAEs

Reversible fluorescence photoswitching can be achieved when one isomer of a photochromic compound is fluorescent and the other one is non-fluorescent. In typical fluorescent photoswitchable DAEs, the open-ring isomer is fluorescent, while the closed-ring isomer is non-fluorescent. Therefore, the fluorescence can be observed in the initial (open-ring) state, and it decreases depending on the population of the photogenerated closed-ring isomer upon irradiation with ultraviolet (UV) light. In the present review, such conventional “turn-off” mode fluorescent DAEs are excluded because a great number of such derivatives have been synthesized so far, and the corresponding results have already been summarized in previous excellent reports10,15. On the other hand, turn-on mode fluorescent DAEs, which are initially non-fluorescent and are activated to a fluorescent state upon photoisomerization reactions, have recently been developed18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Such turn-on mode fluorescent DAEs are suitable for bioimaging applications, including super-resolution microscopies.

Some “turn-on” mode fluorescent DAEs have been developed by replacing the ethene moiety to other heterocycle units instead of the perfluoro- or perhydro-cyclopentene unit18. The closed-ring isomers of these derivatives exhibit fluorescence, while the fluorescence is lost in the open-ring isomers. However, the fluorescence quantum yields of these molecules are not high enough to apply in the standard methods of super-resolution fluorescence imaging.

Recently, a new type of fluorescent DAE, as shown in Fig. 2, has been developed. Indeed, the sulfone derivatives of 1,2-bis(2-methyl-1-benzothiophen-3-yl)perfluorocyclopentene 1 were first reported by Ahn et al.19. DAE 1 is a typical DAE derivative for which both isomers show very weak fluorescence with quantum yields of 0.012 for the open-ring isomer and 0.0001 for the closed-ring isomer. By oxidizing the sulfur atoms of 1 to sulfones, the fluorescence property of the closed-ring isomer was much improved. The open-ring isomer 2a is colorless and has no absorption band in the visible wavelength region. Upon irradiation with UV light, the photocyclization reaction takes place, and the yellow-colored closed-ring isomer (2b) is produced. Both the open- and the closed-ring isomers of 2 exhibit fluorescence. The fluorescence quantum yield of 2a was reported to be 0.025, which is approximately two times higher than that of the open-ring isomer 1a. On the other hand, the fluorescence quantum yield of 2b is up to 0.011, which is almost 100 times as large as that of the closed-ring isomer 1b. The fluorescence quantum yield of the closed-ring isomer was further improved from 0.011 to 0.19 (about 20 times), when the methyl substituents at the 2- and 2′-positions (reactive carbon atoms) of the benzothiophene-1,1-dioxide groups were replaced with n-heptyl substituents (DAE 3)20. In addition, the fluorescence quantum yield increased up to 0.52 by introducing the acetyl substituents at the 6- and 6′-positions of the benzothiophene-1,1-dioxide groups (DAE 4)20.

Irie and co-workers21,22,23,24 further modified the above DAE derivatives to fulfill the requirements for super-resolution fluorescence imaging, such as (i) the bathochromic shift of the absorption and fluorescence spectra of the closed-ring isomers allowing excitation at wavelengths >488 nm, (ii) increasing the absorption coefficient, and (iii) increasing the fluorescence quantum yield. They found that the fluorescence quantum yield was dramatically improved, and all requirements for super-resolution fluorescence imaging can be fulfilled by introducing both aryl substituents, such as phenyl-rings (DAE 5) or thiophene-rings (DAE 6), at the 6- and 6′-positions of the benzothiophene-1,1-dioxide groups21 and short alkyl substituents at the 2- and 2′-positions (Fig. 3a)22.

a Molecular structures and photochromism of turn-on mode fluorescent DAE derivatives 5 and 6. b Absorption spectra of 5a (black dashed line), 5b (black solid line), and the photostationary state (PSS) under irradiation with 313 nm light (black dotted line) in 1,4-dioxane (2.0 × 10–5 M) and the fluorescence spectrum of 5b (green solid line) under irradiation with 488 nm light. c Absorption spectra of 6a (black dashed line), 6b (black solid line), and PSS under irradiation with 365 nm light in 1,4-dioxane (1.0 × 10–5 M) and the fluorescence spectrum of 6b (red solid line) under irradiation with 532 nm light. d Photographs of 1,4-dioxane solutions containing 5 and 6 before and after irradiation with 365 nm light under irradiation with 488 nm blue light (left-side solution containing 5) and 532 nm green light (right-side solution containing 6). (Reprinted with permission from Uno et al.21. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society)

Figure 3b shows the absorption and fluorescence spectra of 5 having ethyl substituents at the 2- and 2′-positions and phenyl substituents at the 6- and 6′-positions of the benzothiophene-1,1-dioxide groups in 1,4-dioxane. The open-ring isomer 5a has no absorption band in the visible wavelength region. Upon irradiation with UV light, a new absorption band ascribed to the closed-ring isomer appears at 456 nm and the bright green fluorescence under excitation with 488 nm light can be clearly observed (Fig. 3b). The absorption coefficient and the fluorescence quantum yield of 5b in 1,4-dioxane are 4.6 × 104 M−1 cm−1 and 0.87, respectively. These values are suitable for the super-resolution fluorescence imaging. Although the fluorescence quantum yield slightly decreases with increasing solvent polarity, the yield is high even in polar ethanol (Φf ~ 0.76). Upon irradiation with visible (>480 nm) light, the absorption band at 456 nm and the fluorescence intensity decreased and returned to the initial state. By replacing the phenyl rings with thiophene rings (DAE 6), the absorption band of the closed-ring isomer was shifted to longer wavelengths (500 nm), and intense red-orange fluorescence at around 620 nm was observed under excitation with 532 nm laser light, as shown in Fig. 3c, d. The fluorescence quantum yield of 6b reached 0.78 in 1,4-dioxane. This turn-on fluorescence photoswitching from a completely dark state to a highly fluorescent state is particularly useful for super-resolution fluorescence imaging. Furthermore, 6b exhibits excellent fatigue resistance under irradiation with visible (>440 nm) in 1,4-dioxane, which is superior to that of Rhodamine 101 in ethanol. Further investigations regarding the effect of aryl substituents at the 6- and 6′-positions and alkyl substituents at the 2- and 2′-positions on the photoswitching performance and oxidized terarylene derivatives have been carried out23,24,25,26,27,28.

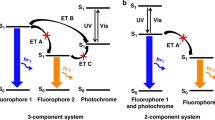

Molecular systems consisting of fluorescent and photochromic moieties

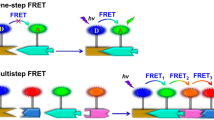

In the abovementioned inherently fluorescent DAEs, the fluorescence process and the photochromic reaction compete with each other. A convenient approach to prepare molecules showing both an efficient photochromic reactivity and a bright fluorescence simultaneously is to combine photochromic and fluorescent chromophores in a molecule through a non-conjugated spacer unit. Förster-type resonance energy transfer (FRET) or photoinduced intramolecular electron transfer (IET) mechanisms are adopted to reversibly switch the fluorescence property. Photoinduced modulation of absorption properties or oxidation/reduction potentials of the DAE unit causes fluorescence switching. In DAE-based photochromic FRET (pcFRET) systems, a fluorophore was used as a fluorescence donor and connected to a DAE unit playing the role of a photoswitchable energy acceptor via a spacer linker. Only the closed-ring isomer of the DAE unit has an absorption band overlapping the fluorescence band of the fluorophore, while the absorption band of the open-ring isomer locates in the wavelength region shorter than the fluorescence band. Therefore, when the DAE is in the open-ring form, the donor fluorescence is not perturbed by the DAE unit and remains at a high level. On the other hand, when the DAE converts to the closed-ring form, energy transfer from the donor fluorophore to the acceptor DAE closed-ring isomer takes place, and the fluorescence is quenched. Based on this mechanism, a large number of highly fluorescent photoswitchable DAEs have been designed and synthesized29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Some of these derivatives can achieve reversible fluorescence photoswitching even at the single-molecule level31,32,33.

Among such successful examples, Zhu and co-workers37 reported that excellent fluorescence on–off contrast can be achieved by combining multiple DAEs to one fluorophore. They synthesized perylenemonoimide dyes modified by one-DAE (PMI-1DAE), two-DAE (PMI-2DAE), and three-DAE units (PMI-3DAE) (Fig. 4a) and compared their fluorescence photoswitching properties (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, the fluorescence on–off contrast at photostationary state (PSS) was dramatically improved by increasing the number of DAE units (Fig. 4c). The fluorescence quenching ratio of PMI-3DAE at PSS exceeds 10,000 and the fluorescence quenching efficiency reaches 100% shortly under UV light irradiation. Based on such excellent fluorescence photoswitching properties of PMI-3DAE, they demonstrated the photo-rewritable fluorescence patterning, all-optical transistors, and super-resolution fluorescence imaging with sub-100-nm resolution.

a Molecular structures of perylenemonoimide dye-modified DAEs (PMI-1DAE, PMI-2DAE, and PMI-3DAE). b Table of optical properties of PMI-1DAE, PMI-2DAE, and PMI-3DAE in toluene. c The polynomial fitting of the fluorescence quenching efficiency Q(t) versus photoconversion yield α(t). The inset is the calculated fluorescence quenching ratio Rcal = 1/[1 − α(t)]n. The concentration is 1.0 × 10−6 M in toluene. (Reprinted with permission from Li et al.37. Copyright 2014 Nature Publishing Group)

On the other hand, the fluorescence switching by the FRET mechanism has an inherent drawback. The quenching by the intramolecular energy transfer to the closed-ring isomer induces an undesirable ring-opening (cycloreversion) reaction. To avoid such an undesired reaction, it is required to separate the absorption spectra of both isomers of the photochromic unit and the fluorescence spectrum of the fluorescent unit and achieve the reversible photoswitching of the fluorescence property under such conditions. The IET process can be utilized as the fluorescence quenching process to satisfy such requirements38. The mechanism is based on changes in oxidation/reduction potentials of the photoswitching DAE unit. When the oxidation or reduction potential differences are large enough to induce the electron transfer between the fluorescent unit and one of the isomers of the DAE unit, the photochromic reaction of the DAE unit induces fluorescence photoswitching. The electron transfer mechanism allows the molecular design in such a manner that the absorption bands of both isomers of the DAE unit are positioned at shorter wavelengths than the fluorescence spectrum of the fluorescent unit. The absorption bands localized in the near-UV or blue region of the spectrum enable proper decoupling between the photochromic reaction and the fluorescence detection. According to this concept, some DAEs linked with fluorescent perylenebisimide (PBI) have been synthesized by Fukaminato et al.39,40,41 and Würthner et al.42,43. After several trials, Fukaminato and co-workers41 succeeded in designing a DAE-PBI dyad (Fig. 5a), which can completely avoid the cycloreversion reaction induced by the energy transfer quenching and achieve the efficient reversible fluorescence photoswitching via a photoinduced electron transfer (PET) with non-destructive readout capability even at the single-molecule level.

a Photochromism and molecular structure of 7. b Absorption and fluorescence spectra of each component of 7 in 1,4-dioxane. Absorption spectra of the open-ring isomer of the DAE unit (black), the closed-ring isomer of the DAE unit (blue), and the PBI unit (red) and fluorescence spectrum of the PBI unit (green). c Relative fluorescence quantum yields as a function of the dielectric constant for the open-ring isomer 7a (open-circle) and the closed-ring isomer 7b (closed-circle). d Non-destructive fluorescence readout capability of both open- and closed-ring isomers of 7. Fluorescence intensities at 568 nm under excitation at 532 nm of 7a (open-circle) and 7b (closed-circle) were plotted against irradiation time. e Single-molecule fluorescence photoswitching in a poly(methyl acrylate) (PMA) thin film containing 7. Sequential wide-field fluorescence images of 7 embedded in PMA film (upper) and the corresponding fluorescence intensity trajectory of a single molecule of 7, represented as a white circle in the upper images. (Reprinted with permission from Fukaminato et al.41. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society)

In this molecular design, it is favorable to employ S,S-dioxide DAE derivatives as electron acceptors and fluorescent PBI chromophores as electron donors to avoid spectral overlap. The fluorescence spectrum of the PBI unit does not overlap with the absorption spectra of both isomers of S,S-dioxide DAE derivatives (Fig. 5b). In this molecule, the fluorescence quantum yield of the closed-ring isomer dramatically decreases when the dielectric constant of the solvent increases >5, while that of the open-ring isomer remains almost constant with an increase in the dielectric constant of the solvent (Fig. 5c). In polar solvents, the fluorescence is therefore reversibly switched by alternate irradiation with visible (445 nm) and UV (365 nm) light, and the excitation light for fluorescence readout does not induce any photochromic reaction due to the absence of the absorption band of both isomers of the DAE unit at this wavelength. Indeed, the fluorescence intensities of both isomers stay constant even after 2 h under continuous irradiation with 532 nm laser light (2.5 mW cm−2) (Fig. 5d). A non-destructive fluorescence readout based on the photochromic IET mechanism was successfully demonstrated in dyad 7 even at the single-molecule level, as shown in Fig. 5e41.

Hybrid materials composed of fluorophores and DAE molecules

Inorganic and organic hybrid nanosystems

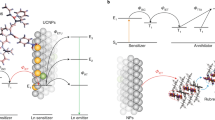

Luminescent organic–inorganic nanohybrid systems, such as silica NPs, quantum dots (QDs), and upconverting NPs (UCNPs), have been recently developed and widely applied to optical data storage, bioimaging, and super-resolution imaging.

Among various host matrices for the construction of hybrid NPs, silica is known to have the great advantages of biocompatibility, excellent optical quality, and easy functionalization44. More importantly, organic molecules can be easily loaded into hybrid siloxane networks. Therefore, many researchers select this option to prepare inorganic–organic hybrid fluorescent NPs for various applications. For example, Hell and co-workers45 synthesized photoswitchable fluorescent silica NPs encapsulating a fluorescent DAE derivative (Fig. 6a). The fluorescence intensity can be clearly modulated upon alternate irradiation with UV and visible light based on the abovementioned pcFRET mechanism. Kim and co-workers46 prepared photoswitchable fluorescent silica NPs via a straightforward one-pot multicomponent copolymerization by a simple mixing of a Cy3 fluorophore and a DAE derivative (Fig. 6b). This procedure is useful not only for avoiding complicated syntheses but also for achieving tunable efficiency of fluorescence photoswitching. Similar strategies have also been developed by other researchers to construct other silica-based fluorescent photoswitchable NPs47,48.

a Molecular structure of the fluorescent molecular switch connected with silica nanoparticles and a TEM image of the nanoparticles. (Reprinted with permission from Fölling et al.45. Copyright 2008 John Wiley and Sons). b Monodisperse silica nanoparticles prepared by the one-pot copolymerization reaction for reversible fluorescence photoswitching. c Photoswitching QDs coated with an amphiphilic photochromic polymer. (Reprinted with permission from Díaz et al.51. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society). d Two-way photoswitching of a DAE using UCNPs by verifying only the intensity of NIR (980 nm) light. (Reprinted with permission from Boyer et al.54. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society)

In contrast to the broad spectrum of typical fluorescent NPs, QDs have several advantages for biological applications, such as high emission quantum yield, broad excitation and narrow emission bands, and excellent photostability49,50. In order to obtain QDs with photoswitchable emission, DAE derivatives were introduced into the surface organic layer, and the emission property was controlled by either the PET or FRET mechanism. Jovin and co-workers51,52 prepared photoswitchable QDs based on a pcFRET mechanism (Fig. 6c). DAEs were covalently linked to an amphiphilic polymer that self-assembles with the lipophilic chains surrounding commercial hydrophobic core–shell CdSe/ZnS QDs. The photoswitchable QD retains all of the desirable properties of the original QD, and the brightness of the emission can be modulated by light.

UCNPs composed of NaYF4 doped with certain lanthanide dopants, which can absorb multiple near-infrared (NIR) photons and convert them into higher-energy (UV or visible) light with relatively narrow bands, have recently received significant attention for possible uses in biological applications53. Compared to the conventional fluorescent materials, UCNPs show very low background fluorescence, minimal photo-damage, and deep penetration of light. In addition, UCNPs generate large anti-Stokes shifts of up to 500 nm, which results in well-separated emission and excitation bands. Based on these advantages, many research groups have developed photoswitchable UCNPs incorporating DAE derivatives, and successful examples have been reported recently54,55,56,57. Branda and co-workers54,55,56 employed NaYF4 nanocrystals doped with lanthanide ions to remote-control photoswitching of DAEs using NIR light (980 nm). They successfully demonstrated the selective generation of UV and visible light under high- and lower-power densities, respectively (Fig. 6d). The high-power infrared irradiation on UCNPs enabled the generation of UV light at λ = 365 nm, which in turn induced the photocyclization reaction of DAE units. On the contrary, the photocycloreversion reaction of DAE units was simply triggered by decreasing the power density of the infrared light irradiation. This result offers a highly convenient and versatile method to spatially and temporally regulate photochromic reactions with a single light source by just changing the excitation light power.

NPs based on organic molecules

Typical organic fluorophores are emissive in dilute solutions, but usually their fluorescence intensity is dramatically reduced in the solid state. This is called “aggregation-caused quenching” (ACQ). Therefore, the application of fluorescent photoswitchable materials was seriously limited in the highly concentrated solid or assembled states. In this context, Kim and co-workers58 prepared DAE crosslinked polyamidoamine dendritic nanoclusters modified with Cy3 as a label dye and demonstrated in vivo fluorescence imaging in living zebra fish and cells (Fig. 7). This strategy of minimizing fluorescence self-quenching produced high fluorescence on–off contrast even in living systems.

a Molecular structures of a switching unit DAE and fluorophore Cy3. b Photoswitching experiments performed on living zebrafish with dendritic nanoclusters internalized by permeation upon alternate irradiation with UV (365 nm) and visible (590 nm) light. Red circles represent the Cy3 moieties as covalently attached to the surface of dendrimers. (Reprinted with permission from Kim et al.58. Copyright 2012 John Wiley and Sons)

On the other hand, in order to overcome the problem of ACQ, aggregation-induced emission (AIE) or aggregation-induced enhanced emission (AIEE) molecules have been developed59,60,61. AIE or AIEE molecules show no or very weak emission in the dilute state, but the fluorescence intensity is considerably enhanced in the aggregated (highly concentrated) state. Several examples of DAE derivatives having an AIE or AIEE property have been reported so far. For example, Park and co-workers62 prepared highly fluorescent photoswitchable DAE NPs 8 by introducing a 1-cyano-trans-1,2-bis-(4′-methylbiphenyl)ethylene unit, which is one of the representative AIEE derivatives, into the DAE unit (Fig. 8a). DAE 8a shows almost no fluorescence in tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution (Φf = 0.00002), while the NPs with a size of 40–275 nm (Fig. 8b) emit fluorescence (Φf ~ 0.05) around 490 nm and show reversible fluorescence photoswitching. Such fluorescence enhancement was observed even for a poly(methyl methacrylate) film containing a very high concentration of 8a (approx. 3 × 10−1 M), and reversible fluorescence imaging was successfully demonstrated (Fig. 8c).

a Molecular structure of DAE 8 and the fluorescence images of its (I), (III) THF solution and (II), (IV) colloidal suspension of fluorescent photochromic organic nanoparticles. b FE-SEM image of nanoparticles of 8a prepared by the reprecipitation method from a THF/water mixture. c Photo-rewritable fluorescence imaging on the polymer film loaded with 20 wt% of 8a by using UV (365 nm) and visible light (>500 nm). (Reprinted with permission from Lim et al.62. Copyright 2004 John Wiley and Sons)

Polymer NPs (P-dots) have also attracted attention because of their higher brightness compared to organic fluorophores and suitability for various biological applications63. P-dots are easily prepared by injecting a small portion of a dilute polymer solution in a water-miscible organic solvent into water, and their size can be controlled through the concentration of the polymer solution. In addition, P-dots can protect them from degradation in many cases. Harbron et al.64 first reported DAE-doped fluorescent P-dots and demonstrated the reversible fluorescence photoswitching at the single-particle level. Recently, Osakada et al.65,66 and Chiu et al.67 independently reported DAE-doped P-dots for fluorescence photoswitching for biological imaging. They were prepared by the simple reprecipitation method from a THF solution containing fluorescent polymer, DAE, and an amphiphilic polystyrene polymer having hydrophilic side chains of ethylene oxide (PEG) terminated with carboxylic groups (PS-PEG-COOH). Osakada et al.65,66 demonstrated the repeatable fluorescence photoswitching not only in a fixed cell but also in a live macrophage cell. Chiu et al.67 also proposed using photoswitchable P-dots for “optical painting,” to select targeted single adherent cells from tissue in order to sort and recover for genetic analysis as described in the following section.

Very recently, Su et al.68 reported a novel fluorescent photoswitchable DAE derivative having a benzothiaziazole (BTD) fluorophore (DAE-BTD dyad 9) (Fig. 9a). The open-ring isomer of DAE 9 shows strong emission in dilute solution as well as in the NP state with almost the same properties (wavelength, efficiency, photochromic reactivity). In addition, DAE-BTD dyad 9 shows remarkable amplification of fluorescence quenching in the NP state. In a dilute solution, the fluorescence intensity linearly decreases with increasing population of the non-fluorescent closed-ring isomer along with the photocyclization reaction, as shown in Fig. 9b. On the other hand, in the case of the NP state, the initial fluorescence decreases dramatically at very low conversion yield. More than 90% of the fluorescence is quenched for only 1% of the closed-ring isomer, and the fluorescence can be considered to reach almost zero (>99% fluorescence quenching) for only 5% of the closed-ring isomer (Fig. 9c). Similar amplification of fluorescence photoswitching can be observed in other photoswitchable assembled systems such as silica NPs combined with DAEs45, P-dots containing DAEs69, and polymer systems70,71,72, but the quenching efficiency has been greatly enhanced by several orders of magnitude. Such a fascinating “giant amplification of fluorescence photoswitching” can be ascribed to a very efficient intermolecular FRET process between the fluorescent units and the closed-ring isomer of the DAE units within the NPs prepared exclusively from 9a (Fig. 9d). From the theoretical calculations, it is estimated that a single closed-ring isomer (9b) can quench the fluorescence of >400 neighboring molecules. Such giant amplification of fluorescence photoswitching is highly beneficial to many applications that require sensitive fluorescent photoswitches working with a minimal number of photons.

a Molecular structure and photochromism of DAE-BTD dyad 9. b, c Fluorescence intensity versus conversion yield (C.Y.) correlation plots and photographs of sample cuvettes for DAE-BTD dyad 9, b in solution (2 × 10−6 M in THF), and c in NP suspension (10−5 M in H2O/THF 80:20), under increasing UV (blue dots) and visible (red dots) exposure times. d Illustration of the FRET-induced “giant amplification of fluorescence photoswitching” in NPs. Left: every NP is initially composed of emissive molecules 9a densely packed together. Right: when a few molecules are promoted to non-fluorescent 9b (blue/dark red dyads) at very low UV irradiation conditions, a large number of 9a are quenched (gray/dark red dyads) by the long-range intermolecular FRET process from 9a to 9b within each Förster sphere. (Reprinted with permission from Su et al.68. Copyright 2016 John Wiley and Sons)

Kobatake and co-workers72 also observed amplification of fluorescence photoswitching even in dilute solution for random and alternative copolymers bearing DAE and fluorene units in their side chains (poly(DAEx-co-FLy) and poly(DAE-alt-FL), respectively, Fig. 10a). Although the fluorescence intensity of the DAE-fluorene dyad (DAE-FL, Fig. 10a) linearly decreases with the concentration of non-fluorescent closed-ring isomer produced under UV light, those of the copolymers significantly decreased with an increase in the conversion yield from the open- to the closed-ring isomer (Fig. 10b). This amplification of fluorescence photoswitching in DAE-FL copolymers is attributed to the efficient intermolecular energy transfer between large numbers of fluorene units to few closed-ring isomers of DAE units in a polymer chain. More interestingly, the magnitude of amplification of fluorescence quenching in an alternative copolymer is much higher than that in a random copolymer, which suggests that the monomer sequence is quite an important parameter to realize highly efficient fluorescence photoswitching in polymer systems.

a Molecular structures of DAE-FL dyad, poly(DAEx-co-FLy) and poly(DAE-alt-FL). b Normalized fluorescence intensity excited at 390 nm plotted vs. the photocyclization conversion of DAE-FL in n-hexane (black circles), poly(DAE-co-FL) in THF (blue circles), and poly(DAE-alt-FL) in THF (red circles). (Reprinted with permission from Nakahama et al.72. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society)

Applications

Fluorescence labeling and bioimaging

Fluorescence imaging has become an indispensable tool for visualizing dynamic protein interactions, intracellular networks, and material transport in living cells and revealing biological mechanisms in real time. Fluorescence labeling molecules (probes) are important to the advancement of such bioimaging technologies, which are widely used for the monitoring of internal cellular processes73. Although much progress has been made in designing fluorescent probes for bioimaging in the past few decades, most of these conventional probes are irreversible to a certain event or non-dynamical to environmental stimuli. In contrast, photoswitchable signals can be exploited to overcome inherent limitations, such as interferences with light absorption, scattering, and autofluorescence from biological tissues. In an autofluorescence-rich in vivo environment, for example, modulating the fluorescence signal of probes can be synchronized with the remote photoswitching frequency, which can allow the dynamic signal to be distinguished from the static autofluorescence background and thus can improve the capability of signal identification74. Therefore, the development of a novel photoswitchable fluorescent labeling molecule would be a powerful tool in elucidating the physiological dynamics in living cells. Up to the present, in view of this background, some conceptual examples of bioimaging and fluorescence labeling based on fluorescence photoswitchable molecular systems have been demonstrated in small transparent animals, such as Caenorhabditis elegans, mouse, or zebrafish.

Soh and co-workers75 designed and synthesized a photoswitchable protein label based on DAE derivative 10 with a fluorescein and succinimidyl ester unit (Fig. 11a). The fluorescence of the labeled protein can be reversibly switched by alternate irradiation with UV and visible light. Since the succinimidyl ester unit can be easily converted to other functional groups, such as a Ni2+-preloaded bis(nitrilotriacetic acid) (NTA-Ni2+) unit, which is a specific recognition unit for histidine, this molecular design has great potential for future functional labeling and imaging of biological systems with photoswitchable molecules.

a Molecular structure and reversible fluorescence photoswitching of DAE 10 for labeling of proteins. b Molecular structure of a photoswitchable fluorescent biomarker 11 and photoswitching of images of living HeLa cells. Upon UV light irradiation, a cytoplasmic fluorescence signal appeared. Subsequent visible light irradiation completely abolished the fluorescence signal. (Reprinted with permission from Pang et al.76. Copyright 2012 The Royal Society of Chemistry)

Ahn and co-workers76 applied a DAE-based “turn-on” fluorescent photoswitchable probe 11 to live cell imaging (Fig. 11b). They demonstrated the dynamic fluorescence signal photoswitching in real time at the single live cell level and found that 11 was non-cytotoxic, cell-permeable, and accumulated preferentially in the cytoplasm.

Many inorganic or organic fluorescent photoswitchable NPs combined with DAE derivatives have been utilized as photoswitchable biomarkers in fluorescence bioimaging of fixed cells, live cells, and even animals46,55,56,57,58,65,66,67,77,78. In these examples, the emission from the probed NPs can be reversibly quenched by only one state of the DAE unit, typically through an energy transfer process. While these examples have overcome some drawbacks of conventional fluorescent probes, there are still some serious problems. One noticeable problem is the low fatigue resistance of fluorescent photoswitchable NPs in prolonged experiments and frequent “on–off” switching cycles. The use of inorganic QDs as the fluorescent component in partnership with a robust DAE photoswitch can minimize such problem. In particular, UCNP-modified DAE derivatives have great potential as biomarkers because all photoswitching processes can be operated by a single NIR light source, which allows us to avoid the use of UV or visible light and minimizes photodamage during in vivo experiments. The Branda group55,56 and Li et al.57 have successfully demonstrated the fluorescence bioimaging of living C. elegans and a nude mouse under NIR excitation at 980 nm. These systems not only have the capacity to reversibly control the emission intensity through selective absorption but also have the opportunity to achieve multicolored probes for in vivo bioimaging.

A unique application of fluorescent photoswitchable NPs was reported by Chiu et al. very recently67. Analysis of specific cells in tissues contributes to the discovery of the biological interactions that drive diseases and aging. Although various methods, such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), limiting dilution, cloning ring, panning, column chromatography, and magnetic sorting, have been developed to select cells of interest according to their unique characteristics, such as morphology and biomarkers, distinctive problems still remain for each method. Therefore, there is still a need for a simple and high-throughput approach that enables individual adherent cells to be imaged in their native microenvironment and then selected and isolated. For this issue, Chiu et al.67 proposed using photoswitchable P-dots for “optical painting,” to select targeted single adherent cells from tissue in order to sort and recover them for genetic analysis. They conjugated the photoswitchable P-dots to streptavidin and labeled cells via biotinylated primary antibodies (Fig. 12a). And then, to achieve the separation of cells modified with photoswitchable P-dots, the cells were irradiated with a 633 nm focused laser; “painted” cells were visible under a microscope and were sorted by using FACS analysis (Fig. 12b–d). Furthermore, they successfully applied this method for DNA sequencing, mRNA extraction, and the sorting of a mouse pancreas tumor tissue slice. Compared with the conventional immuno-fluorescence staining method, their approach allows cells to be selected based on spatial and morphological or micro-environmental information and may be used to mark cells on the basis of any desired dynamic properties, such as cell division rates, cell migration, differentiation, behavioral phenotypes, response to drugs, and so on. Such a capability will enhance the study of single cells within tissues and should be useful for both basic biological studies and clinical research.

a Schematic depiction of P-dot formation, cellular labeling using P-dots, and “painting” of labeled cells with light, followed by the sorting and isolation of painted cells. b Selective painting of individual cells with 633 nm laser light. c A simple scheme illustrating the ensemble-decision aliquot ranking (eDAR) concept. The insets photographs show the flow being switched to the collecting filter and then switched back shortly. A food dye was added to visualize the streamline. Scale bar, 50 μm. d The bright-field and e fluorescence images of the collected cells in the filters with a 5-μm height and 5-μm width. Scale bar, 50 μm. (Reprinted with permission from Kuo et al.67. Copyright 2016 Nature Publishing Group)

Super-resolution fluorescence imaging

Fluorescence photoswitching has another advantage in improving the detectability as well as the spatial resolution of fluorescence imaging. In principle, the diffraction limit originating from the wave properties of light restricts the optical microscope resolution to ∼300 nm, a level two of orders of magnitude coarser than nanoscale molecules; thus many intracellular organelles and their associated molecular structures remained unresolvable. However, we can now overcome the diffraction limit and achieve 20–30-nm lateral and 50–60-nm axial resolutions in biological fluorescence imaging by taking advantage of the fluorescence switching events of fluorescent photoswitchable molecules5,12,13. The concept of such super-resolution fluorescence imaging was first proposed by Hell and Wichmann79, and several techniques such as photoactivation localization microscopy (PALM), stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM), reversible saturable (switchable) optically linear fluorescence transitions (RESOLFT), and others have been developed in recent years, and the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for this technique in 201480.

The controllable fluorescence of on–off photoswitching plays a critical role in these revolutionary super-resolution imaging techniques; thus the optimization of photophysical and photochemical properties of fluorescent photoswitchable molecules is essential. The general requirements for super-resolution probes are efficient photoswitchability and high brightness of the fluorescence. In addition, other optimizations of the photoswitching property are required depending on the principle of super-resolution techniques. For example, in PALM/STORM, the turn-off rates should be very low, while, in RESOLFT microscopy, the turn-off rates are required to be high. The detailed explanation of this point was well described in refs. 24,25. Several researchers tried to develop fluorescent DAEs and demonstrate super-resolution fluorescence imaging by using such derivatives.

Zhu and co-workers81 demonstrated the sub-100-nm super-resolution fluorescence imaging of aggregates and the nanostructure of block copolymers based on the localization technique by using an AIE-type DAE derivative and a trident DAE-3PMI derivative described above, respectively. Wöll et al.82 also demonstrated PALM super-resolution imaging of block copolymer cylindrical micelles forming string structures by using a turn-on-type DAE derivative for which the closed-ring isomer of DAE-bearing sulfone groups is fluorescent. In this example, the resolution was estimated to be approximately 50 nm with respect to full-width at half-maximum (FWHM). Such turn-on-type DAEs are suitable for the application of super-resolution probes compared to multichromophoric systems in which the fluorophore is connected to the DAE unit via covalent bonds because of their small size of labeling structures and less complicated synthesis.

Although the results of super-resolution fluorescence imaging based on fluorescent photoswitchable DAE derivatives has been gradually increased in this way, the demonstration is still limited to a polar media. The most attractive target in the super-resolution imaging is the direct visualization of organizations in biomaterials. Inherent hydrophobicity and poor water solubility of DAE derivatives prevent the application in purely aqueous conditions. To solve this problem, Hell’s and Irie’s groups83,84 attempted to develop suitable water-soluble DAEs that can be used for super-resolution imaging under biologically relevant conditions. They designed and synthesized DAE derivatives 12 and 13 with multiple carboxylic acid groups into a turn-on S,S-dioxide DAE unit (Fig. 13a). These derivatives are soluble in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer solution and exhibit reversible fluorescence photoswitching with relatively high contrast and fluorescence quantum yield (>0.3). They first performed RESOLFT super-resolution imaging of fixed immune-labeled Vero cells by using the symmetrical DAE derivative 12 having eight carboxylic acid groups and achieved ~74-nm spatial resolution with respect to the FWHM (Fig. 13b)83. However, DAE derivative 12 is not suitable for STORM due to the low [fluorescence quantum yield]/[cycloreversion quantum yield] ratio (<300). The ratio must be increased by at least one order of magnitude to increase the localization accuracy. They tried to decrease the cycloreversion quantum yield by introducing one or two donor methoxy substituents at para-positions of the terminal phenyl groups84. After several optimizations, a candidate derivative 13 was synthesized for labeling the secondary antibodies, and STORM experiments were carried out in which this derivative showed suitable quantum yields of photocyclization and the photocycloreversion reaction, high brightness, and a high [fluorescence quantum yield]/[cycloreversion quantum yield] ratio (>2000) with antiaggregation properties in PBS buffer solution. Super-resolution imaging of tubulin, vimentin, and nuclear pore complexes was demonstrated based on a wide-field STORM microscope without requiring any additives to the imaging media. Moreover, the super-resolution images can also be acquired by using a single 488 nm laser because of the reversible fluorescence photoswitching by the optical absorption at the very weak hot bands or “Urbach tail”84,85,86. These works will open new paths toward the molecular design of fluorescent dyes for super-resolution bioimaging.

a Molecular structures and photochromism of DAE derivatives 12 and 13. b RESOLFT images of the whole fixed Vero cells immunostained with primary antibodies against α-Tubulin and with the diarylethene 12 attached to the secondary antibodies. Scale bar: 1 μm. The line profiles A–D (averaged over ten adjacent lines) display the regions indicated in the RESOLFT image. (Reprinted with permission from Roubinet et al.83. Copyright 2016 John Wiley and Sons)

Photocontrol of biological functions

A new emerging field is the photoswitching of bioactivity. Fluorescence photoswitchable molecular systems are also useful for such applications because it is possible to perform simultaneous control and monitoring of biological events. Branda and co-workers87 reported photocontrol of paralysis of C. elegans by DAE 14 having N-methylpyridinium groups (Fig. 14a), which shows green-colored fluorescence in the closed-ring isomer (Fig. 14b). The fluorescence in the closed-ring isomer is useful for monitoring the uptake or localization of the compound in C. elegans. Paralysis is induced by the cyclization reaction of DAE by irradiation with UV light, and mobility is restored by the cycloreversion reaction with visible light (Fig. 14c, d). The paralysis in C. elegans is likely a result of interruption of the metabolic electronic pathways due to the unique electron-accepting ability of the closed-ring isomer.

a Molecular structures and photochromism of DAE 14. b Fluorescence microscopy images of C. elegans incubated with (i) 10% DMSO and (ii) photoswitch 14b (12 mM) within the first 10 min and (iii) after 60 min. c The number of mobile, non-responsive, and paralyzed nematodes for samples that have been treated with 14a or 14b compared to controls after 60 min of incubation and d for samples exposed to varying amounts of 14b. (Reprinted with permission from Al-Atar et al.87. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society)

Liu et al.88 designed DAE derivatives selectively responding to biomolecules, such as amyloid-β (Aβ) and DNA. DAE 15 (Fig. 15a) having thiazole orange (TO), which is a cyanine dye with red or NIR emission, exhibited a DNA-gated photochromic property (Fig. 15b). Owing to the strong aggregation property of TO in aqueous solution, the fluorescence of TO in water is very weak (Φf ~ 0.25%). When the surrounding environment of TO changes to hydrophobic conditions, the fluorescence intensity can be drastically increased up to Φf = 3.4%. Furthermore, the molecular conformation of 15a is folded in the photoinactive parallel conformation in aqueous solution because of the intramolecular interaction of TO groups tethered to a central DAE unit. Upon the addition of DNA to an aqueous solution of 15a, the photochromic reactivity of 15a was activated, and the fluorescence intensity was also drastically increased because TO units can bind DNA due to the strong hydrophobic interaction and π–π stacking among the planar chromophores. Thus the fixed parallel conformation is unlocked. Moreover, 15a exhibited different binding patterns toward A-T and G-C base pairs with a great diversity of photophysical properties (absorption, fluorescence, and induced circular dichroism). Based on this unique gated property of 15a, fluorescence imaging of the intracellular behavior of 15 in the HeLa cell line (Fig. 15c) was demonstrated. Intense fluorescence was observed in the nucleolus area when 15a was incubated with fixed HeLa cells, which suggested that the TO units of 15a were located in the hydrophobic environment due to binding to DNA in the cell and that 15a preferably localized in the nucleolus area. Indeed, reversible fluorescence photoswitching was observed in a fixed HeLa cell, which indicated that the conformation of 15a was unlocked from the photoinactive parallel conformation by binding to DNA in the cell.

a Molecular structure of 15 and b schematic diagram illustrating the DNA-responsive properties combined with gated photochromism. c Fluorescence images of fixed HeLa cells incubated with 15a (10 μM) for 10 min followed by Hoechst33258 (10 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C. A selected cell shows reversible fluorescence off-switching with 405 nm and recovery using a 633 nm laser. (Reprinted with permission from Liu et al.88. Copyright 2014 The Royal Society of Chemistry)

Lv et al. further developed Aβ-responsive fluorescent DAE derivatives with one or two aminonaphthalenl-2-cyano-acrylate targeting units of Aβ89. Aβ is the major component of senile plaques and plays an important role in the pathophysiology and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. A significant increase in the fluorescence intensity with a slight blue-shift was observed upon the addition of Aβ aggregates, while no change in fluorescence properties was observed upon addition of Aβ monomer and other aggregated proteins. This indicated the high selectivity of such fluorescent DAE derivatives for Aβ aggregates. To further evaluate whether these fluorescent photoswitchable probes could stain amyloid deposits in brain tissue, they attempted to incorporate them into brain sections of mice. As expected, the fluorescence probes could specifically highlight Aβ deposits in the brain sections, and the fluorescence intensity could be switched upon alternating irradiation with UV and visible light. These biomolecule-gated photoswitchable fluorescent probes might provide a new window for bioimaging with high resolution and open new applications in the near future.

Fluorescence color modulation

Multicolor fluorescent nanomaterials that exhibit multiple distinguishable emission signals are especially attractive due to their potential applications in flexible full-color displays, in next-generation lighting sources, and in probes to decipher multiple biological events simultaneously90,91. A large number of fluorescence-color phototunable DAE-based NPs have been developed by incorporating two or more energy level-matched fluorescent dyes into NPs together with the DAE unit and controlling the fluorescence intensity of each component with a pcFRET mechanism. For example, Park and co-workers92,93 prepared highly fluorescent dual-color photoswitchable NPs and polymer films consisting of a DAE derivative combined with different colored AIE fluorophores or ESIPT (excited-state intramolecular proton transfer) fluorophores. By optimizing the FRET efficiency, they successfully demonstrated multi-stimulus fluorescence patterning, reversible fluorescence photoswitching, and non-destructive fluorescence readout of fluorescence signal in these works.

Kim and Lee94 reported a dual-color photoswitchable fluorescent P-dot 16 containing a DAE derivative and a dual-color emissive conjugated polymer (CP) containing phenylene and benzothiadiazole (BTD) units in the same polymer backbone (Fig. 16a). In the open-ring isomer of the DAE unit, P-dot 16a shows both blue (approximately 380 nm) and green (approximately 540 nm) fluorescence originating from the phenylene and BTD units (but the appearing fluorescence color is green), because of inefficient energy transfer from CP to the open-ring isomer of DAE. Upon irradiation with UV light, the fluorescence color dramatically changed from green to blue. This fluorescence color change is attributed to the efficient energy transfer from only the BTD unit to the closed-ring isomer of the DAE unit in the P-dots because of the much larger spectral overlap between the fluorescence band of the BTD unit and the absorption band of the DAE unit compared to the case between the phenylene unit and the DAE closed-ring isomer unit. To elucidate the possibility of biological applications of P-dot 16, they loaded P-dots 16a into zebrafish and performed fluorescence color photoswitching in living zebrafish (Fig. 16b). Before UV light irradiation, strong fluorescence was observed from the living zebrafish in emission channels of blue and green without any noticeable difference in the shape of the zebrafish. Upon irradiation with UV light to the zebrafish, the green fluorescence was quenched, but the blue fluorescence still remained. Such a photoswitching property of fluorescence color in biological samples might be useful to achieve high-accuracy analysis of biological events under a fluorescence microscope.

a Molecular structures of the molecules in P-dots 16 and fluorescence color switching between green and blue along with the photochromic reactions of the DAE units. b A photograph and fluorescence images before and after UV irradiation (254 nm) taken at the head and at the tail of zebrafish incubated with P-dots 16. (Reprinted with permission from Kim et al.94. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society)

Although several fluorescence color photoswitchable systems have been reported recently as mentioned above, all of these systems are based on the ratiometric color change between two different colored fluorophores. In this case, the variation of fluorescence color changes is inherently limited. In principle, full-color fluorescence can be produced by the combination of red (R), green (G), and blue (B) emissions. Therefore, the methodology of fluorescence-color photoswitching for multicomponent systems containing RGB fluorophores together will be important. Akagi and co-workers95 tried to demonstrate RGB-based multicolor fluorescence photoswitching by utilizing the combination of photoresponsive and non-photoresponsive fluorescent nanospheres. In this work, they prepared photoresponsive nanospheres with R, G, and B fluorescence made from CPs connecting DAE moieties in the side chains (P1, P2, and P3) (Fig. 17a). They also prepared the same emission colored non-photoresponsive nanospheres made from CPs without DAE moieties in the side chains (P1′, P2′, and P3′). Then three types of mixtures were prepared by mixing the polymer nanospheres as follows: P1′, P2, and P3 for white-to-blue (W–B); P1, P2′, and P3 for white-to-green (W–G); and P1, P2, and P3′ for white-to-red (W–R) (Fig. 17b). Each system includes three RGB fluorescent nanospheres in which two polymers include DAE moieties at the side chains, whereas the other does not. In each system, the three polymers were mixed at the appropriate ratio, and all mixtures generated white fluorescence with B, G, and R emission bands when the DAE moiety was in the open-ring form. Upon irradiation with UV light to each system, the intensity of the fluorescence bands corresponding to the photoresponsive polymers drastically decreased owing to the efficient energy transfer from polymer backbones to the closed-ring form of the DAE units, as shown in Fig. 17c. On the other hand, the fluorescence of the non-photoresponsive polymers remained even after UV irradiation because the DAE moiety was absent. Therefore, for the W–B, W–G, and W–R systems, the white fluorescence switched to B, G, and R fluorescence, respectively, upon UV light irradiation. For each system, the RGB fluorescence was then converted to white fluorescence through irradiation with visible light. The reversible photoswitching between white and RGB fluorescence was also demonstrated in cast films. This multicolor fluorescence photoswitching system is very interesting, but the tunable fluorescence color is completely dependent on the combination of photoresponsive and non-photoresponsive polymers; therefore, the variation of fluorescence color changes is still limited. Ideal multicolor fluorescence photoswitchable systems require selective photoswitching of each color component and high contrast with a minimum crosstalk between them, even in a multicomponent system.

a Molecular structures of photoresponsive conjugated polymers, P1, P2, and P3. b Photographs of photoswitching between white and RGB-colored fluorescence in mixed nanosphere suspensions in water. In the systems, one of the photoresponsive polymers (P1–P3) was replaced by a corresponding polymer analog, P1′–P3′, which had no DAE moiety in the side chains. c Fluorescence spectra for the white-to-blue (W–B), white-to-green (W–G), and white-to-red (W–R) systems under UV irradiation of λ = 360 nm. (Reprinted with permission from Bu et al.95. Copyright 2014 Nature Publishing Group)

Probable reasons to prevent selective and high-contrast multicolor fluorescence photoswitching are the broad absorption property in both isomers of the DAE derivatives and the imperfect photoconversion from the open- to the closed-ring isomer. Fukaminato et al.96,97 attempted to overcome this drawback by employing the giant amplification of fluorescence photoswitching property of photoswitchable fluorescent NPs as mentioned above. They prepared two kinds of photoswitchable fluorescent NPs consisting of 9 and 17 (Fig. 18a) in which each molecule has a different pair of DAE and fluorescence units. Both NPs exhibited remarkable non-linear fluorescence quenching upon irradiation with UV light. In addition, these NPs showed clear wavelength dependence on fluorescence photoswitching behavior. Under irradiation with 385 nm UV light, the fluorescence intensity of 9 preferentially turned off compared to that of 17, attributed to the difference in absorption coefficients, approximately two times, between 9 and 17 at this wavelength. The fluorescence intensity of 17 slowly decreased and retained over 60% of the initial fluorescence intensity, while the fluorescence intensity of 9 remarkably decreased down to 7% of the initial intensity. Such a significant difference in the fluorescence quenching ratio originated from the non-linear fluorescence quenching property because a small difference in conversion yield under this condition produces a large difference in fluorescence intensities between 9 and 17 in this system. In addition, upon irradiation with 680 nm light to the dark state solution, the fluorescence intensity of 9 gradually increased and perfectly recovered up to the initial level, while the fluorescence intensity of 17 never changed, even after irradiation for an extended period, because 17 has no absorption at this wavelength. These results clearly indicated that the fluorescence photoswitching of 9 and 17 can be selectively modulated by optimizing the irradiation wavelength condition appropriately. Based on this result, they demonstrated wavelength-selective and high-contrast multicolor fluorescence photoswitching in a mixed suspension of 9 and 17 NPs, where each NP was prepared separately and then mixed with the other (Fig. 18b). White fluorescence was observed for the mixture of orange (9) and cyan (17) NPs. In the initial state, a broad fluorescence spectrum that covered the whole visible-wavelength region with two peaks at 493 and 567 nm was observed, and a clear white emission was visualized under excitation with 405 nm light (Fig. 18b (i)). Upon irradiation with 385 nm light, the orange-emission band preferentially decreased and the emission color clearly changed from white to cyan (Fig. 18b (ii)). Upon sequential irradiation with 313 nm light, the cyan-emission band completely disappeared and no emission was observed (Fig. 18b (iii)). Subsequently, upon irradiation with 680 nm light, the fluorescence band originating from 9 selectively increased and the emission color clearly changed from dark to orange (Fig. 18b (iv)). Sequentially, upon irradiation with 560 nm light, the fluorescence band originating from 17 started to recover and the emission color turned back to white. Such high-contrast emission color photoswitching was never accomplished in the case of a mixture of 9 and 17 in THF. They also demonstrated sequential RGB fluorescence color photoswitching in multicomponent photoswitchable fluorescent NPs containing three different colored molecules by optimizing the magnitude of amplification of fluorescence quenching and the molar ratios of each component. These results clearly support the advantage of multicolor fluorescence photoswitching systems based on the giant amplification of fluorescence photoswitching property in photochromic NPs, and ideal full-color fluorescence photoswitching will be realized in the near future.

a Molecular structures of fluorescent DAE derivatives 9 and 17. b Multicolor fluorescence photoswitching in a water suspension of the mixture of 9 and 17 NPs upon sequential irradiation with an appropriate wavelength of light: fluorescence spectra (i) before photoirradiation (or after irradiation with >560 nm light to the solution of (iv)) (white emission), (ii) after irradiation with 385 nm light (cyan emission), (iii) after sequential irradiation with 313 nm light (dark), and (iv) after sequential irradiation with 680 nm light (orange emission). Photographs of the same cuvettes for the mixture suspension of 9 and 17 NPs in the corresponding states are shown in the insets. (Reprinted with permission from Ishida et al.96. Copyright 2017 The Royal Society of Chemistry)

Conclusion

In summary, a wide variety of examples combining DAE units with fluorescent dyes, from the molecular level to the nanoscale, have been described during the past decade. In most of the systems, RET is responsible for the fluorescence photoswitching: the fluorophore is fully emissive when the DAE is in its open form, whereas it is quenched when the DAE is in its closed form due to the large spectral overlap between its absorption spectrum and the fluorescence spectrum of the fluorescent unit. This conceptual design not only leads to efficient fluorescence photoswitching but also suffers from several drawbacks (destructive read-out, limited contrast, single emission color, UV excitation, etc.). For these reasons, many alternative strategies have been proposed recently. As typical examples, “turn-on” DAE molecules with benzothiophene-1,1-dioxide side-groups are particularly suitable for super-resolution imaging, whereas molecular dyads with DAE and fluorescent moieties involving IET processes are very effective for optical memories with a non-destructive readout capability. Inorganic UCNPs decorated by DAEs can be fully triggered by NIR light, whereas preparation of silica nanosystems, QDs, or polymer NPs doped with DAE represents an efficient route to reach photocontrolled emission with high brightness. NPs based on aggregated organic molecules, such as aggregation-induced emission fluorophores and DAE units, have shown extremely interesting non-linear fluorescence photoswitching features (giant amplification effect) leading to unprecedented contrast and switching rates and enable multicolor emission possibilities. As a result, novel application fields have appeared: in biology, fluorescent DAEs have been successfully employed not only as protein labels, probes, and biomarkers in live cells and living organisms but also as tunable and switchable emitters for super-resolution imaging technologies. The great diversity of designs, properties, and applications of fluorescent DAE-based molecules and nanosystems makes them excellent candidates to develop novel molecular constructs with unexplored behaviors.

References

Feringa, B. L. The art of building small: from molecular switches to molecular motors. J. Org. Chem. 72, 6635–6652 (2007).

Irie, M. Photochromism and molecular mechanical devices. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 81, 917–926 (2008).

Bianco, A., Perissinotto, S., Garbugli, M., Lanzani, G. & Bertarelli, C. Control of optical properties through photochromism: a promising approach to photons. Laser Photon. Rev. 5, 711–736 (2011).

Velema, V. A., Szymanski, W. & Feringa, B. L. Photopharmacology: beyond proof of principle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2178–2191 (2014).

Heilemann, M., Dedecker, P., Hofkens, J. & Sauer, M. Photoswitches: key molecules for subdiffraction-resolution fluorescence imaging and molecular quantification. Laser Photon. Rev. 3, 180–202 (2009).

Bouas-Laurent, H. & Dürr, H. Organic photochromism. Pure Appl. Chem. 73, 639–665 (2001).

Zhang, J., Zou, Q. & Tian, H. Photochromic materials: more than meets the eye. Adv. Mater. 25, 378–399 (2013).

Yildiz, I., Deniz, E. & Raymo, F. M. Fluorescence modulation with photochromic switches in nanostructured constructs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1859–1867 (2009).

Yun, C., You, J., Kim, J., Huh, J. & Kim, E. Photochromic fluorescence switching from diarylethenes and its applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 10, 111–129 (2009).

Fukaminato, T. Single-molecule fluorescence photoswitching: design and synthesis of photoswitchable fluorescent molecules. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 12, 177–208 (2011).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, K., Wang, J., Tian, Z. & Li, A. D. Q. Photoswitchable fluorescent nanoparticles and their emerging applications. Nanoscale 7, 19342–19357 (2015).

Hell, S. W. Far-field optical nanoscopy. Science 316, 1153–1158 (2007).

Fürstenberg, A. & Heilemann, M. Single-molecule localization microscopy- Near-molecular spatial resolution in light microscopy with photoswitchable fluorophores. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 14919–14930 (2013).

Irie, M. Diarylethenes for memories and switches. Chem. Rev. 100, 1685–1716 (2000).

Irie, M., Fukaminato, T., Matsuda, K. & Kobatake, S. Photochromism of diarylethene molecules and crystals: memories, switches, and actuators. Chem. Rev. 114, 12174–12277 (2014).

Matsuda, K. & Irie, M. Diarylethene as a photoswitching unit. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 5, 169–182 (2004).

Tian, H. & Yang, S. Recent progress on diarylethene based photochromic switches. Chem. Soc. Rev. 33, 85–97 (2004).

Cipolloni, M. et al. New thermally irreversible and fluorescent photochromic diarylethenes. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 4765–4771 (2008).

Jeong, Y.-C., Yang, S. I., Ahn, K.-H. & Kim, E. Highly fluorescent photochromic diarylethene in the closed-ring form. Chem. Commun. 2503–2505 (2005).

Jeong, Y.-C., Park, D. G., Lee, I. S., Yang, S. I. & Ahn, K.-H. Highly fluorescent photochromic diarylethene with an excellent fatigue property. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 97–103 (2009).

Uno, K. et al. In situ preparation of highly fluorescent dyes upon photoirradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13558–13564 (2011).

Takagi, Y. et al. Photoswitchable fluorescent diarylethene derivatives with short alkyl chain substituents. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 11, 1661–1665 (2012).

Takagi, Y. et al. Turn-on mode fluorescent diarylethenes: control of the cycloreversion quantum yield. Tetrahedron 73, 4918–4924 (2017).

Irie, M. & Morimoto, M. Photoswitchable turn-on mode fluorescent diarylethenes: strategies for controlling the switching response. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 91, 237–250 (2018).

Nevskyi, O. et al. Fluorescent diarylethene photoswitches – a universal tool for super-resolution microscopy in nanostructured materials. Small https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201703333 (2018).

Taguchi, M., Nakagawa, T., Nakashima, T. & Kawai, T. Photochromic and fluorescence switching properties of oxidized triangle terarylenes in solution and in amorphous solid states. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 17425–17432 (2011).

Gillanders, F., Giordano, L., Diaz, S. A., Jovin, T. M. & Jares-Erijman, E. A. Photoswitchable fluorescent diheteroarylethenes: substituent effects on photochromic and solvatochromic properties. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 13, 603–612 (2014).

Barrez, E., Laurent, G., Pavageau, C., Sliwa, M. & Métivier, R. Comparative photophysical investigation of doubly-emissive photochromic-fluorescent diarylethenes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 2470–2479 (2018).

Giordano, L., Jovin, T. M., Irie, M. & Jares-Erijman, E. A. Diheteroarylethenes as thermally stable photoswitchable acceptors in photochromic fluorescence resonance energy transfer (pcFRET). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 7481–7489 (2002).

KawaiT., SasakiT. & IrieM. A photoresponsive laser dye containing photochromic dithienylethene units. Chem. Commun. 8, 711–712 (2001).

Irie, M., Fukaminato, T., Sasaki, T., Tamai, N. & Kawai, T. A digital fluorescent molecular photoswitch. Nature 420, 759–760 (2002).

Fukaminato, T., Sasaki, T., Kawai, T., Tamai, N. & Irie, M. Digital photoswitching of fluorescence based on the photochromism of diarylethene derivatives at a single-molecule level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 14843–14849 (2004).

Fukaminato, T. et al. Photochromism of diarylethene single molecules in polymer matrices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5932–5938 (2007).

Bossi, M., Belov, V., Polyakova, S. & Hell, S. W. Reversible red fluorescent molecular switches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 7462–7465 (2006).

Pärs, M. et al. An organic optical transistor operate under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 11405–11408 (2011).

Ouhenia-Ouadahi, K. et al. Fluorescence photoswitching and photoreversible two-way energy transfer in a photochrome-fluorophore dyad. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 11, 1705–1714 (2012).

Li, C. et al. A trident dithienylethene-perylenemonoimide dyad with super fluorescence switching speed and ratio. Nat. Commun. 5, 5709 (2014).

Myles, A. J. & Branda, N. R. Controlling photoinduced electron transfer within a hydrogen-bonded porphyrin-phenoxynaphthacenequinone photochromic system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 177–178 (2001).

Odo, Y., Fukaminato, T. & Irie, M. Photoswitching of fluorescence based on intramolecular electron transfer. Chem. Lett. 36, 240–241 (2007).

Fukaminato, T., Doi, T., Tanaka, M. & Irie, M. Photocyclization reaction of diarylethene-perylenebisimide dyads upon irradiation with visible (>500 nm) light. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 11623–11627 (2009).

Fukaminato, T. et al. Single-molecule fluorescence photoswitching of a diarylethene-perylenebisimide dyad: non-destructive fluorescence readout. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 4984–4990 (2011).

Berberich, M., Krause, A.-M., Orlandi, M., Scandola, F. & Würthner, F. Toward fluorescent memories with nondestructive readout: photoswitching of fluorescence by intramolecular electron transfer in a diarylethene-perylene bisimide photochromic system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 6616–6619 (2008).

Berberich, M. et al. Nondestructive photoluminescence read-out by intramolecular electron transfer in a perylene bisimide-diarylethene dyad. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 13651–13664 (2012).

Bonacchi, S. et al. Luminescent silica nanoparticles: extending the frontiers of brightness. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 4056–4066 (2011).

Fölling, J. et al. Synthesis and characterization of photoswitchable fluorescent silica nanoparticles. Small 4, 134–142 (2008).

Jung, H.-y., You, S., Lee, C., You, S. & Kim, Y. One-pot synthesis of monodispersed silica nanoparticles for diarylethene-based reversible fluorescence photoswitching in living cells. Chem. Commun. 49, 7528–7530 (2013).

Edelsztein, V. C., Jares-Erijman, E. A., Müllen, K., Chenna, P. H. D. & Spagnuolo, C. C. A luminescent steroid-based organogel: ON-OFF photoswitching by dopant interplay and templated synthesis of fluorescent nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 21857–21861 (2012).

Shimizu, K. & Kobatake, S. Synthesis and optical properties of fluorescent switchable silica nanoparticles covered with copolymers consisting of diarylethene and fluorene derivatives. ChemistrySelect 2, 5445–5452 (2017).

Michalet, X. et al. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science 307, 538–544 (2005).

Medintz, I. L., Uyeda, H. T., Goldman, E. R. & Mattoussi, H. Quantum dot bioconjugates for imaging, labelling and sensing. Nat., Mater. 4, 435–446 (2005).

Díaz, S. A., Gillanders, F., Etchehon, M. H., Jovin, T. M. & Jares-Erijman, E. A. Photoswitchable water-soluble quantum dots: pcFRET based on amphiphilic photochromic polymer coating. ACS Nano 5, 2795–2805 (2011).

Díaz, S. A. et al. Water-soluble, thermostable, photomodulated color-switching quantum dots. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 263–267 (2017).

Zhou, J., Liu, Q., Feng, W., Sun, Y. & Li, F. Upconversion luminescent materials: advances and applications. Chem. Rev. 115, 395–465 (2015).

Boyer, J.-C., Carling, C.-J., Gates, B. D. & Branda, N. R. Two-way photoswitching using one type of near-infrared light, Upconverting nanoparticles, and changing only the light intensity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 15766–15772 (2010).

Boyer, J.-C. et al. Photomodulation of fluorescent upconverting nanoparticle marker in live organisms by using molecular switches. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 3122–3126 (2012).

Wu, T. et al. Two-colour fluorescent imaging in organisms using self-assembled nano-systems of upconverting nanoparticles and molecular switches. Nanoscale 7, 11263–11266 (2015).

Yang, T. et al. Photoswitchable upconversion nanophosphors for small animal imaging in vivo. RSC Adv. 4, 15613–15619 (2014).

Kim, Y. et al. High-contrast reversible fluorescence photoswitching of dye-crosslinked dendritic nanoclusters in living vertebrates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 2878–2882 (2012).

Hong, Y., Lam, J. W. Y. & Tang, B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 5361–5388 (2011).

An, B.-K., Gierschner, J. & Park, S. Y. π-Conjugated cyanostilbene derivatives: a unique self-assembly motif for molecular nanostructures with enhanced emission and transport. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 544–554 (2012).

Shi, J. et al. Solid state luminescence enhancement in π-conjugated materials: unraveling the mechanism beyond the framework of AIE/AIEE. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 23166–23183 (2017).

Lim, S.-J., An, B.-K., Jung, S. D., Chung, M.-A. & Park, S. Y. Photoswitchable organic nanoparticles and a polymer film employing multifunctional molecules with enhanced fluorescence emission and bistable photochromism. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 6346–6350 (2004).

Wu, C. & Chiu, D. T. Highly fluorescent semiconducting polymer dots for biology and medicine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 3086–3109 (2013).

Davis, C. M., Childress, E. S. & Harbron, E. J. Ensemble and single-particle fluorescence photomodulation in diarylethene-doped conjugated polymer nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 19065–19073 (2011).

Osakada, Y., Hanson, L. & Cui, B. Diarylethene doped biocompatible polymer dots for fluorescence switching. Chem. Commun. 48, 3285–3287 (2012).

Osakada, Y. et al. Live cell imaging using photoswitchable diarylethene-doped fluorescent polymer dots. Chem. Asian J. 12, 2660–2665 (2017).

Kuo, C.-T. et al. Optical painting and fluorescence activated sorting of single adherent cells labelled with photoswitchable Pdots. Nat. Commun. 7, 11468 (2016).

Su, J. et al. Giant amplification of photoswitching by a few photons in fluorescent photochromic organic nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 3662–3666 (2016).

Trofymchuk, K. et al. Exploiting fast excitation diffusion in dye-doped polymer nanoparticles to engineer efficient photoswitching. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 2259–2264 (2015).

Métivier, R. et al. Fluorescence photoswitching in polymer matrix: mutual influence between photochromic and fluorescence molecules by energy transfer processes. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 11916–11926 (2009).

Finden, J., Kunz, T. K., Branda, N. R. & Wolf, M. O. Reversible and amplified fluorescence quenching of a photochromic polythiophene. Adv. Mater. 20, 1998–2002 (2008).

Nakahama, T. et al. Fluorescence on/off switching in polymer bearing diarylethene and fluorene in their side chains. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 6272–6281 (2017).

Giepmans, B. N. G., Adams, S. R., Ellisman, M. H. & Tsien, R. Y. The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science 312, 217–224 (2006).

Tian, Z. & Li, A. D. Q. Photoswitching-enabled novel optical imaging: Innovative solutions for real-world challenges in fluorescence detections. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 269–279 (2013).

Soh, N. et al. A fluorescent photochromic compound for labeling biomolecules. Chem. Commun. 5206–5208 (2007).

Pang, S.-C. et al. Photoswitchable fluorescent diarylethene in a turn-on mode for live cell imaging. Chem. Commun. 48, 3745–3747 (2012).

Jeong, K. et al. Conjugated polymer/photochromophore binary nanococktails: Bistable photoswitching of near-infrared fluorescence for in vivo imaging. Adv. Mater. 25, 5574–5580 (2013).

Feng, G., Ding, D., Li, K., Liu, J. & Liu, B. Reversible photoswitching conjugated polymer nanoparticles for cell and ex vivo tumor imaging. Nanoscale 4, 4141–4147 (2014).

Hell, S. W. & Wichmann, J. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: Stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 19, 780–782 (1994).

Hell, S. W. Nobel Lecture: Nanoscopy with freely propagating light. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1169–1181 (2015).

Li, C. et al. Photoswitchable aggregation-induced emission of a dithienylethene-tetraphenylethene conjugate for optical memory and super-resolution imaging. RSC Adv. 3, 8967–8972 (2013).

Nevskyi, O., Sysoiev, D., Oppermann, A., Huhn, T. & Wöll, D. Nanoscopic visualization of soft matter using fluorescent diarylethene photo switches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12698–12702 (2016).

Roubinet, B. et al. Carboxylated photoswitchable diarylethenes for biolabeling and super-resolution RESOLFT microscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 15429–15433 (2016).

Roubinet, B. et al. Fluorescence photoswitchable diarylethenes for biolabeling and single-molecule localization microscopies with optical superresolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 6611–6620 (2017).

Arai, Y. et al. One-colour control of activation, excitation and deactivation of a fluorescent diarylethene derivative in super-resolution microscopy. Chem. Commun. 53, 4066–4069 (2017).

Kashihara, R., Morimoto, M., Ito, S., Miyasaka, H. & Irie, M. Fluorescence photoswitching of a diarylethene by irradiation with single-wavelength visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16498–16501 (2017).

Al-Atar, U., Fernandes, R., Johnsen, B., Baillie, D. & Branda, N. R. A photocontrolled molecular switch regulates paralysis in a living organism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 15966–15967 (2009).