Abstract

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) and primary headaches are common pain conditions and often co-exist. TMD classification includes the term ‘headache secondary to TMD' but this term does not acknowledge the likelihood that primary headache pathophysiology underpins headache causing painful TMD signs and symptoms in many patients. The two disorders have a complex link and we do not fully understand their interrelationship. However, growing evidence shows a significant association between the two disorders. This article reviews the possible connection between temporomandibular disorders and primary headaches, specifically migraine, both anatomically and pathogenetically.

Key points

-

The co-existence of temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) and primary headaches implies a potential connection in their underlying mechanisms.

-

Diagnosis and treatment can be challenging due to the complex interrelationship between TMD and primary headaches, particularly migraines, underscoring the need for comprehensive pain history.

-

Some individuals might experience painful TMD signs and symptoms as a result of an underlying headache disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) is an umbrella term for a heterogeneous condition of musculoskeletal disorders involving pain and/or functional limitations in the masticatory muscles, temporomandibular joints (TMJ) and associated structures in orofacial region.1 The condition is considered as the most common cause of non-dental orofacial pain and as the second most commonly occurring musculoskeletal condition.2 Approximately 40-70% of the general population experience some symptoms and signs of TMD.3,4,5 These conditions are found more often in women and commonly appears between the ages of 20-50 years.6,7A number of pain conditions has been associated with TMD, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, headaches, irritable bowel syndrome and chronic back pain.8,9 The diagnosis and classification of TMD have improved following the publication of the comprehensive and newly recommended Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD)10 and the International Classification of Orofacial Pain (ICOP).11

The two classification systems broadly classify TMD as muscle-related (or myogenous pain, including temporalis and masseter muscle pain) and joint-related problems that may cause pain (disc-displacement with and without reduction, subluxation and inflammatory change of the joint). TMDs, by definition, do not include other pathology, for example, neoplasia, infection or trauma. These classifications are outlined in Appendix 1.

Migraine is a subtype of primary headache condition manifested by a familial paroxysmal neurological disorder characterised by spontaneous or triggered headache attacks variably associated with autonomic disturbances, such as nausea, increased sensitivity to external stimuli (photophobia, phonophobia), and, less commonly, hemiparesis or aphasia.12 Migraine attacks usually last 4-72 hours.12 Migraine has a significant impact on the individual's quality of life and is ranked by the World Health Organisation as one of the 20 most debilitating diseases in the world.13 The best recognised diagnostic criteria for migraine is the third edition of International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3)12 (Appendix 2).

TMD and migraine are both characterised by pain in the head and/or face, and both conditions are more common in women, especially those of childbearing age.14,15,16 Although they are two completely different disorders, overlap is common, often leading to misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of one or other condition. Several studies have explored prevalence of the comorbidity and relationship between migraine and TMD (Table 1).17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 From these previous studies, it is sensible to suggest that TMD and migraine may have bidirectional association. TMD may be the original cause of headaches and may exacerbate and worsen existing headaches. Migraine headache may well trigger and aggravate TMD, or these two conditions may be comorbid. This review aims to explore the relationship between TMD and migraine, focusing on anatomical and pathophysiological aspects.

Epidemiology

TMD pain was observed in patients with primary headache; a population study reported 27% of headache people (any primary headaches) experienced TMD pain, while only 15% of the non-headache group suffered from TMD pain. Also, the prevalence of headache was noticeably higher for the TMD group (72%) than the control group (31%).34 Migraine, particularly, is the most prevalent headache in TMD population (55%), followed by tension-type headache (30%).20 The odds ratio for migraine in those with TMD was 2.76, which represents that individuals with TMD are two times more likely to develop migraine greater than those without TMD condition.20 Moreover, an increased number of TMD symptoms was associated with higher prevalence of migraine headache and chronic daily headaches.18

The OPPERA study revealed that migraine and frequent headaches are a significant risk factor for the development of first-onset TMD symptoms.35 The headache prevalence and frequency elevated during the observation period among patients who developed TMD. Interestingly, the most outstanding change is that the prevalence of definite migraine episodes increased ten-fold in the TMD group. The result of this study suggested another aspect of relationship between TMD and migraine in that migraine per se might also be an exacerbating factor for TMD.35

From the published studies, the evidence on the influence of TMD on migraine progression or chronicity is limited and inconclusive. A previous study explored the role of TMD in the development of migraine and reported that frequent symptoms of TMD and frequent headache were strongly associated (odd ratio = 4.1), suggesting that TMD might be a potential factor to induce chronic migraine.36 Furthermore, Bevilaqua et al. has reported that migraine patients with TMD are 2-3 times more likely to experience cutaneous allodynia (pain occurs due to non-painful stimuli).37,38 Migraine pain, however, can cause not only pain in maxillary (V2) and mandibular (V3) nerve areas, but also allodynia, a source of accompanying discomfort and pain that is probably misdiagnosed as TMD.39

Relationship between TMD and migraine

A growing body of research has established several biopsychosocial factors associated with increased risk for the development and persisting TMDand migraine.40,41,42,43,44 It is therefore important to recognise that various biopsychosocial factors, including shared physiology, psychological behaviours and environmental factors, may as well contribute to the relationship between them. While this review primarily focuses on the anatomical and physiological aspects of the relationship between TMD and migraine, it is essential to acknowledge the potential influence of other comorbid pain conditions and psychological variables during the diagnostic process.

Anatomical and clinical perspectives

Migraine pain commonly occurs in the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (V1) and occasionally radiates to the V2 and V3 branch.45,46,47 Isolated facial pain in migraine, that is, pain occurring only in the V2 or V3 region, is rare48 and is recently classified by the ICOP as isolated orofacial migraine.11 During the onset or attack of migraine, many patients experience spontaneous pain in the teeth, cheek, masticatory muscles and periauricular region. Such these presentations of migraine can understandably be misdiagnosed as odontogenic pain, sinusitis or TMD.25,49,50 This misdiagnosis also led to inappropriate treatment as evidenced by case reports of migraine patients being mistakenly treated as toothaches, resulting in tooth extractions, which unsurprisingly do not improve the pain.51,52

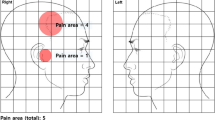

Similar to the distribution of migraine pain, TMD pain can radiate widely in the orofacial and cranial regions.53 A cross-sectional study found that the incidence of undiagnosed TMD in headache patients was 25%.54 Among primary headaches, the incidence of TMD was highest in migraine patients compared with the other diagnoses.54 This could possibly suggest that TMD pain could be the cause of pain in some patients with headaches, given the close anatomical relationship between the muscles of mastication, TMJ and the head.

Pathophysiological perspectives

In addition to the anatomical overlap between TMD and migraine, a growing number of studies have demonstrated the relatedness of these disorders in terms of pathophysiological mechanism.

Peripheral and central sensitisation

One of the possible links between migraine and TMD is peripheral and central sensitisation.34 When peripheral injury triggers pain signals in the trigeminal nerve, local tissue inflammation releases cytokines and pro-inflammatory mediators that stimulate and amplify the pain response. Peripheral sensitisation decreases the depolarisation threshold so that normal stimuli are perceived as painful. The persistence of peripheral pain input can lead to central sensitisation, resulting in increased excitability of central pain pathways. Central sensitisation is the physiological hallmark of persistent pain syndromes and is responsible for the clinical symptoms of hyperalgesia and allodynia.46 Therefore, normal or sub-threshold stimulators from TMJ and associated structures may become migraine-inducing factors or vice versa.

A prominent example of peripheral input from both conditions might be the occurrence of myofascial pain. The involvement of myofascial mechanisms in migraines have been reported.55,56,57,58,59,60 However, the exact pathophysiological relationship between myofascial pain and migraines remains unclear. Myofascial trigger points (MTP) can be classified into active and latent trigger points.61 Active trigger points cause constant pain, while latent trigger points only elicit pain when manually palpated.61 It has been hypothesised that sustained muscle contraction in MTP leads to hypoxia and ischemia, resulting in increased concentrations of inflammatory mediators, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P.58 It seems that MTP in the muscle of mastication is common in both conditions, myofascial TMD and migraine. Although these studies have examined MTP in multiple muscles of the head and neck, it is still uncertain which specific muscles are most affected.62

Several studies have showed a high occurrence of active and latent MTP in individuals with migraine, both during and after a migraine attack.56,57,59 Additionally, palpating these MTP can even induce a migraine attack in some migraineurs.56,63 This indicates that individuals with migraines may experience ongoing myalgia even after their migraine attacks have subsided. Consequently, there is a possibility of misdiagnosing muscle-related TMD in migraineurs who are currently not exhibiting symptoms of migraines at the time.

The myofascial mechanism in migraines can potentially be explained by both a bottom-up and a top-down model.62,64 In the bottom-up model, peripheral nociceptive transmission sensitises the central nervous system, resulting in a lower pain threshold. On the other hand, central sensitisation may contribute to the development of myofascial trigger points. These models may help explain the constant myalgia in migraineurs after a migraine attacks. Although the myofascial trigger points are common in both myofascial TMD and migraine patients, it should not be yet assumed that the presence of masticatory myalgia is directly and solely related to the comorbidity of both conditions.

Cross-excitation in the trigeminal ganglion

TMD and migraine might trigger each other because of excitation of one trigeminal branch activates the other branch. Although the dura mater is innervated mainly by V1 branch, it is also supplied by the meningeal fibres of branches V2 and V3.51,65 Therefore, the anatomical connection of these fibres may play a role in cross-excitation and explain why migraine pain may occur in the V2 and V3 regions. The peripheral afferents from both meningeal tissues, where migraine attacks occur, and the TMJ apparatus project towards the trigeminal ganglion. Nociceptive input from both intracranial and extracranial tissues converges in the nucleus caudalis and then projects to the thalamus, cortex and limbic system.66 Therefore, it can be hypothesised that the nociceptive inputs from the periphery (TMJ and masticatory muscles) could trigger the migraine-associated neurons at the level of the trigeminal nuclei.

Neuromusculoskeletal dysfunction of the cervical spine (C2, C3) has been found to contribute to both TMD and migraine via the trigeminocervical complex (TCC).67,68 TCC is a key pathway that elucidates the relationship between the upper neck, TMJ and trigeminal nerve, which can be associated with a variety of disorders of the neck, face and head. The convergence of the nociceptive pathways of the upper cervical spine and the trigeminal system allows pain signals from the neck to be referred to the trigeminal sensory receptive fields in the face and head. Thus, not only is migraine a comorbidity of TMD, but neck pain and cervicogenic headache may be a non-skippable disorder that should be considered in TMD treatment.

Molecular link

The release of proinflammatory molecules could play a role in the sensitisation and association between TMD and migraine. In particular, the level of CGRP are significantly higher in TMD patients when compared to healthy controls, and the magnitude of CGRP levels correlates positively with pain intensity.68 CGRP is released from trigeminal fibres and is the most potent known peptidergic dilator of peripheral and cerebral blood vessels and an important factor in the development of neurogenic inflammation and migraine.69 CGRP receptors are widely expressed in the trigeminal system. Therefore, it is possible to hypothesise that the expression of CGRP in the trigeminal ganglion because of TMD pathology could stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and then cause activation of the intra-trigeminal ganglion, leading to excitation of peripheral and meningeal afferents and the development of migraine. However, the relationship between the two diseases is potentially dynamic. We can suggest that the increase in CGRP levels during migraine attacks can also trigger and worsen TMD symptoms.

Differentiation of TMD and migraine

The aim of the assessment is to determine the underlying cause of TMD pain, distinguishing between cases in which TMD is comorbid with migraine and cases in which migraine pain mimics TMD. One of the key features of migraine presentation (within or without an actual attack) is sensitivity to light, noise and other sensory stimuli (Table 2). When patients present with TMD symptoms, apart from investigation by following the TMD diagnostic criteria, assessment of headache history is essential for clinician to avoid overlooking underlying migraine.

Migrainous symptoms can be assessed by using a self-answer questionnaire: the ID-migraine item.70 The questionnaire facilitates rapid detection of migraine in primary care setting and it consists of three screening questions that inquire about headache-related disability, nausea and sensitivity to light in the past three months (Appendix 2). The ID-migraine indicates the presence of migraine if a patient answered ‘yes' to at least two of the three questions. Diagnostic accuracy revealed a sensitivity of 0.81, a specificity of 0.75, and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.93. The three-item ID migraine questionnaire then also proved beneficial for detecting migraine in patients with TMD and orofacial pain.71 The diagnostic values showed a sensitivity of 0.58, a specificity of 0.98, and a PPV of 0.93. Interestingly, Kim's study showed the same PPV (93%) as the original study. Hence, the ID-migraine questionnaire can be a quick, applicable and valuable tool for dentists to screen patients with headache symptoms in their clinical setting. For more generic headache screening and monitoring, the HIT-6 is advised to assess the impact of headache but would not act as a diagnostic aid specific to migraine.72,73

Regarding the clinical examination for diagnosing TMD, the International Network for Orofacial Pain and Related Disorders Methodology has provided comprehensive tools.74 While the reproducible pain on TMJ and masticatory muscle palpation plays a crucial role in diagnosing TMD, it is important to be cautious of myofascial pain among individuals with migraines, as mentioned previously. It is worth noting that even if migraine symptoms are not observed, there is still a possibility of misdiagnosing painful TMD based on muscle palpation. Thus, a comprehensive approach that includes a thorough history interview and assessment of clinical findings becomes imperative in identifying the potential cause of symptoms. We suggest a simple consideration to exclude migraine in patients with positive TMD symptoms (Fig. 1). This approach would benefit those patients with either atypical TMD symptoms or those who have failed multiple TMD treatments. If migraine is the fundamental drive behind the patient's presentation with TMD signs and remains unaddressed, then treatment will inevitably fail. Once the optimal diagnosis is made, there are helpful treatment guidelines for clinicians to ensure that proper treatment is appropriately provided, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline for headache management75 and the clinical pathway for adults with headache and facial pain by the National Neurosciences Advisory Group.76

Headache or migraine attributed to TMD

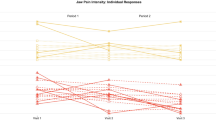

This review earlier outlines that migraine sometimes behaves similarly to TMD pain; on the contrary, TMD can also induce headache and it is recognised as headache attributed to TMD (HATMD) according to the classification of DC/TMD10 and ICHD-312 (Appendix 3). The confirmation of familiar headache when jaw movement or muscle palpation during clinical examination is key for identifying HATMD. Individuals with migraine pain who are found to have TMD pain as the original source of migraine should be diagnosed as having migraine attributed to TMD, and solo TMD treatment, not additional headache treatment, may be sufficient to improve the headache. Published evidence of this is found in one study of patients with HATMD who underwent TMD treatment only. The result showed a significant correlation between a reduction in TMD symptoms and decrease in the frequency and intensity of headaches.77 On the other hand, if the TMD symptoms originate from migraine, as described above, a single TMD treatment will not benefit these patients. Therefore, treatment response may be a hint to helping the physician determine the true cause of the pain condition.

HATMD is common among patients with chronic myogenous TMD.77 Headaches often present as migraine77 and are associated with higher headache frequency and familiar masticatory muscle pain responses on examination.78 The study has shown that evoked pain on clinical examination was a crucial diagnostic component of HATMD, already included in the diagnostic criteria for HATMD.78 Headaches originating from TMD may have several causes: pain in the temporalis muscle (the muscle located in the temple area) or pain in other masticatory muscles or in the TMJ radiating to the temporal region. To ensure appropriate and comprehensive management, it is necessary to determine the underlying condition, such as primary headache, cooccurring with TMD. The ambiguity between HATMD, especially tension-typed headache and myalgia of the masseter muscles, has been discussed.79 The site of pain (temporal region) between the two diagnoses largely overlapped. Most people were diagnosed with HATMD along with myalgia of the temporalis muscle. Therefore, they suggested that HATMD and myalgia of the temporalis muscle could be considered as a single clinical entity. As migraine can be initiated by the onset of any pain within the trigeminal system (for example toothache), this may further undermine HATMD being a single clinical entity.80

Conclusion

TMD and migraine are prevalent and highly inter-related. Distinguishing TMD and migraine can be challenging, especially when both disorders co-exist in a single individual. Understanding the relationship between TMD and migraine is essential and using a simple structured pain history, including headache, would improve the recognition of pain comorbidity and determine whether the patient has migraine mimicking TMD or whether it is TMD in isolation. The crucial message is that it is essential to exclude migraine and other primary headaches that can potentially cause or exacerbate TMD symptoms, thus ensuring that the patient receives appropriate treatment. In addition, it is essential to recognise when TMD may precipitate or worsen ongoing headaches, which requires a dual approach to patient care by optimising TMD care and headache management. Moreover, the need for specific studies on the relationship between the two conditions may encourage clinical researchers to conduct further studies to prove the link between TMD and migraine headaches and provide more effective treatment.

References

De Leeuw R, Klasser G D. Orofacial Pain: Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis, and Management. 6th ed. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing, 2018.

Magnusson T, Egermark I, Carlsson G E. A longitudinal epidemiologic study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders from 15 to 35 years of age. J Orofac Pain 2000; 14: 310-319.

Gesch D, Bernhardt O, Alte D et al. Prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in an urban and rural German population: results of a population-based Study of Health in Pomerania. Quintessence Int 2004; 35: 143-150.

Progiante P, Pattussi M, Lawrence H, Goya S, Grossi P K, Grossi M L. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in an Adult Brazilian Community Population Using the Research Diagnostic Criteria (Axes I and II) for Temporomandibular Disorders (The Maringá Study). Int J Prosthodont 2015; 28: 600-609.

Salonen L, Helldén L, Carlsson G E. Prevalence of signs and symptoms of dysfunction in the masticatory system: an epidemiologic study in an adult Swedish population. J Craniomandib Disord 1990; 4: 241-250.

Ferreira C L, da Silva M A, de Felício C M. Signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in women and men. Codas 2016; 28: 17-21.

Fricton J. Myogenous temporomandibular disorders: diagnostic and management considerations. Dent Clin North Am 2007; 51: 61-83.

Maixner W, Fillingim R B, Williams D A, Smith S B, Slade G D. Overlapping Chronic Pain Conditions: Implications for Diagnosis and Classification. J Pain 2016; 17: 93-107.

Kleykamp B A, Ferguson M C, McNicol E et al. The prevalence of comorbid chronic pain conditions among patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Am Dent Assoc 2022; 153: 241-250.

Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014; 28: 6-27.

Anonymous. International Classification of Orofacial Pain, 1st edition (ICOP). Cephalalgia 2020; 40: 129-221.

Anonymous. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1-211.

Steiner T J, Stovner L J, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z. Migraine remains second among the world's causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain 2020; 21: 137.

Scott S, De Rossi S, Eric T, Stoopler T P. Temporomandibular Disorders And Migraine Headache: Comorbid Conditions? Internet J Dent Sci 2005.

Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 2007; 27: 193-210.

Silberstein S, Loder E, Diamond S e al. Probable migraine in the United States: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Cephalalgia 2007; 27: 220-229.

Ballegaard V, Thede-Schmidt-Hansen P, Svensson P, Jensen R. Are headache and temporomandibular disorders related? A blinded study. Cephalalgia 2008; 28: 832-841.

Gonçalves D A, Speciali J G, Jales L C, Camparis C M, Bigal M E. Temporomandibular symptoms, migraine, and chronic daily headaches in the population. Neurology 2009; 73: 645-646.

Stuginski-Barbosa J, Macedo H R, Bigal M E, Speciali J G. Signs of temporomandibular disorders in migraine patients: a prospective, controlled study. Clin J Pain 2010; 26: 418-421.

Franco A L, Gonçalves D A, Castanharo S M, Speciali J G, Bigal M E, Camparis C M. Migraine is the most prevalent primary headache in individuals with temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain 2010; 24: 287-292.

Gonçalves D A, Bigal M E, Jales L C, Camparis C M, Speciali J G. Headache and symptoms of temporomandibular disorder: an epidemiological study. Headache 2010; 50: 231-241.

Gonçalves D A, Camparis C M, Speciali J G, Franco A L, Castanharo S M, Bigal M E. Temporomandibular disorders are differentially associated with headache diagnoses: a controlled study. Clin J Pain 2011; 27: 611-615.

Hoffmann R G, Kotchen J M, Kotchen T A, Cowley T, Dasgupta M, Cowley A W. Temporomandibular disorders and associated clinical comorbidities. Clin J Pain 2011; 27: 268-274.

Gonçalves M C, Florencio L L, Chaves T C, Speciali J G, Bigal M E, Bevilaqua-Grossi D. Do women with migraine have higher prevalence of temporomandibular disorders? Braz J Phys Ther 2013; 17: 64-68.

Tomaz-Morais J F, de Sousa Lucena LB, Mota I A et al. Temporomandibular disorder is more prevalent among patients with primary headaches in a tertiary outpatient clinic. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2015; 73: 913-917.

Dahan H, Shir Y, Nicolau B, Keith D, Allison P. Self-Reported Migraine and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Are More Prevalent in People with Myofascial vs Nonmyofascial Temporomandibular Disorders. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2016; 30: 7-13.

Florencio L L, de Oliveira A S, Carvalho G F et al. Association Between Severity of Temporomandibular Disorders and the Frequency of Headache Attacks in Women With Migraine: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2017; 40: 250-254.

Di Paolo C, D'Urso A, Papi P et al. Temporomandibular Disorders and Headache: A Retrospective Analysis of 1198 Patients. Pain Res Manag 2017; 2017: 3203027.

Contreras E F, Fernandes G, Ongaro P C, Campi L B, Gonçalves D A. Systemic diseases and other painful conditions in patients with temporomandibular disorders and migraine. Braz Oral Res 2018; 32: 77.

Nazeri M, Ghahrechahi H-R, Pourzare A et al. Role of anxiety and depression in association with migraine and myofascial pain temporomandibular disorder. Indian J Dent Res 2018; 29: 583.

Ashraf J, Zaproudina N, Suominen A, Sipilä K, Närhi M, Saxlin T. Association Between Temporomandibular Disorders Pain and Migraine: Results of the Health 2000 Survey. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2019; 33: 399-407.

Fernandes G, Arruda M A, Bigal M E, Camparis C M, Gonçalves D A. Painful Temporomandibular Disorder Is Associated With Migraine in Adolescents: A Case-Control Study. J Pain 2019; 20: 1155-1163.

Wieckiewicz M, Grychowska N, Nahajowski M et al. Prevalence and Overlaps of Headaches and Pain-Related Temporomandibular Disorders Among the Polish Urban Population. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2020; 34: 31-39.

Mitrirattanakul S, Merrill R L. Headache impact in patients with orofacial pain. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137: 1267-1274.

Tchivileva I E, Ohrbach R, Fillingim R B, Greenspan J D, Maixner W, Slade G D. Temporal change in headache and its contribution to the risk of developing first-onset temporomandibular disorder in the Orofacial Pain: Prospective Evaluation and Risk Assessment (OPPERA) study. Pain 2017; 158: 120-129.

Storm C, Wänman A. Temporomandibular disorders, headaches, and cervical pain among females in a Sami population. Acta Odontol Scand 2006; 64: 319-325.

Bevilaqua-Grossi D, Lipton R B, Napchan U, Grosberg B, Ashina S, Bigal M E. Temporomandibular disorders and cutaneous allodynia are associated in individuals with migraine. Cephalalgia 2010; 30: 425-432.

Grossi D B, Lipton R B, Bigal M E. Temporomandibular disorders and migraine chronification. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2009; 13: 314-318.

Gonçalves D A, Camparis C M, Franco A L, Fernandes G, Speciali J G, Vigal M E. How to investigate and treat: migraine in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012; 16: 359-364.

Rosignoli C, Ornello R, Onofri A et al. Applying a biopsychosocial model to migraine: rationale and clinical implications. J Headache Pain 2022; 23: 100.

Dresler T, Caratozzolo S, Guldolf K et al. Understanding the nature of psychiatric comorbidity in migraine: a systematic review focused on interactions and treatment implications. J Headache Pain 2019; 20: 51.

Fillingim R B, Slade G D, Greenspan J D et al. Long-term changes in biopsychosocial characteristics related to temporomandibular disorder: findings from the OPPERA study. Pain 2018; 159: 2403-2413.

Ohrbach R, Dworkin S F. The Evolution of TMD Diagnosis: Past, Present, Future. J Dent Res 2016; 95: 1093-1101.

Aggarwal V R, Macfarlane G J, Farragher T M, McBeth J. Risk factors for onset of chronic oro-facial pain - results of the North Cheshire oro-facial pain prospective population study. Pain 2010; 149: 354-359.

Peng K-P, Benoliel R, May A. A Review of Current Perspectives on Facial Presentations of Primary Headaches. J Pain Res 2022; 15: 1613-1621.

Yoon M-S, Mueller D, Hansen N et al. Prevalence of Facial pain in migraine: a population-based study. Cephalalgia 2010; 30: 92-96.

Ziegeler C, May A. Facial presentations of migraine, TACs, and other paroxysmal facial pain syndromes. Neurology 2019; 93: 1138-1147.

Lambru G, Elias L-A, Yakkaphan P, Renton T. Migraine presenting as isolated facial pain: A prospective clinical analysis of 58 cases. Cephalalgia 2020; 40: 1250-1254.

Renton T. Tooth-Related Pain or Not? Headache 2020; 60: 235-246.

Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The Sinus, Allergy and Migraine Study (SAMS). Headache 2007; 47: 213-224.

Nixdorf D R, Velly A M, Alonso A A. Neurovascular pains: implications of migraine for the oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2008; 20: 221-235.

Noma N, Shimizu K, Watanabe K, Young A, Imamura Y, Khan J. Cracked tooth syndrome mimicking trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia: A report of four cases. Quintessence Int 2017; 48: 329-337.

Wright E F. Referred craniofacial pain patterns in patients with temporomandibular disorder. J Am Dent Assoc 2000; 131: 1307-1315.

Memmedova F, Emre U, Yalın O Ö, Doğan O C. Evaluation of temporomandibular joint disorder in headache patients. Neurol Sci 2021; 42: 4503-4509.

Olesen J. Clinical and pathophysiological observations in migraine and tension-type headache explained by integration of vascular, supraspinal and myofascial inputs. Pain 1991; 46: 125-132.

Calandre E P, Hidalgo J, Garcia-Leiva J M, Rico-Villademoros F. Trigger point evaluation in migraine patients: an indication of peripheral sensitization linked to migraine predisposition? Eur J Neurol 2006; 13: 244-249.

Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Cuadrado M L, Pareja J A. Myofascial trigger points, neck mobility and forward head posture in unilateral migraine. Cephalalgia 2006; 26: 1061-1070.

Ferracini G N, Chaves T C, Dach F, Bevilaqua-Grossi D, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Speciali J G. Relationship Between Active Trigger Points and Head/Neck Posture in Patients with Migraine. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2016; 95: 831-839.

Giamberardino M A, Tafuri E, Savini A et al. Contribution of myofascial trigger points to migraine symptoms. J Pain 2007; 8: 869-878.

Simons D G, Travell J G. Travell & Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: Trigger Point Manual. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Dommerholt J. Myofascial trigger points: peripheral or central phenomenon? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014; 16: 395.

Do T P, Heldarskard G F, Kolding L T, Hvedstrup J, Schytz H W. Myofascial trigger points in migraine and tension-type headache. J Headache Pain 2018; 19: 84.

Landgraf M N, Biebl J T, Langhagen T et al. Children with migraine: Provocation of headache via pressure to myofascial trigger points in the trapezius muscle? - A prospective controlled observational study. Eur J Pain 2018; 22: 385-392.

Eller-Smith O C, Nicol A L, Christianson J A. Potential Mechanisms Underlying Centralized Pain and Emerging Therapeutic Interventions. Front Cell Neurosci 2018; 23: 35.

Obermann M, Mueller D, Yoon M-S, Pageler L, Diener H, Katsarava Z. Migraine With isolated facial pain: a diagnostic challenge. Cephalalgia 2007; 27: 1278-1282.

Körtési T, Tuka B, Nyári A, Vécsei L, Tajti J. The effect of orofacial complete Freund's adjuvant treatment on the expression of migraine-related molecules. J Headache Pain 2019; 20: 43.

Von Piekartz H, Lüdtke K. Effect of treatment of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) in patients with cervicogenic headache: a single-blind, randomized controlled study. Cranio 2011; 29: 43-56.

Sato J, Segami N, Kaneyama K, Yoshimura H, Fujimura K, Yoshitake Y. Relationship of calcitonin gene-related peptide in synovial tissues and temporomandibular joint pain in humans. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004; 98: 533-540.

Durham P L. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and migraine. Headache 2006; 46: 3-8.

Lipton R B, Dodick D, Sadovsky R et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care. Neurology 2003; 61: 375-382.

Kim S T, Kim C-Y. Use of the ID Migraine questionnaire for migraine in TMJ and Orofacial Pain Clinic. Headache 2006; 46: 253-258.

Kosinski M, Bayliss M S, Bjorner J B et al. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 963-974.

Bayliss M S, Dewey J E, Dunlap I et al. A study of the feasibility of Internet administration of a computerized health survey: the headache impact test (HIT). Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 953-961.

The International Network for Orofacial Pain and Related Disorders Methodology. TMD Assessment/Diagnosis. Available at https://ubwp.buffalo.edu/rdc-tmdinternational/tmd-assessmentdiagnosis/rdc-tmd/ (accessed January 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Headaches in over 12s: diagnosis and management. 2021. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg150 (accessed January 2023).

National Neuroscience Advisory Group. Optimum clinical pathway for adults with headache and facial pain. 2021. Available at https://www.nnag.org.uk/optimal-clinical-pathway-for-adults-with-headache-facial-pain (accessed January 2023).

Hara K, Shinozaki T, Okada-Ogawa A et al. Headache attributed to temporomandibular disorders and masticatory myofascial pain. J Oral Sci 2016; 58: 195-204.

Tchivileva I E, Ohrbach R, Fillingim R B et al. Clinical, psychological, and sensory characteristics associated with headache attributed to temporomandibular disorder in people with chronic myogenous temporomandibular disorder and primary headaches. J Headache Pain 2021; 22: 42.

Exposto F G, Renner N, Bendixen K H, Svensson P. Pain in the temple? Headache, muscle pain or both: A retrospective analysis. Cephalalgia 2021; 41: 1486-1491.

Reyes A J, Ramcharan K, Maharaj R. Chronic migraine headache and multiple dental pathologies causing cranial pain for 35 years: the neurodental nexus. BMJ Case Rep 2019; 12: 230248.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pankaew Yakkaphan conceived original idea and drafted the work. Leigh-Ann Elias, Priya Thimma Ravindranath and Tara Renton revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2024.

About this article

Cite this article

Yakkaphan, P., Elias, LA., Ravindranath, P. et al. Is painful temporomandibular disorder a real headache for many patients?. Br Dent J 236, 475–482 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7178-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7178-1