Abstract

Introduction Literature surrounding the definition, portrayal and teaching of professionalism in dentistry is widespread. However, there has been substantially less focus on the boundaries of professionalism and what constitutes unprofessional or a lapse in professionalism.

Aims What about a dentist's conduct calls their professionalism into question? In exploring this, we shed light on where the boundary between professional and unprofessional conduct is blurred.

Methods Drawing on data from a larger study, we conducted a thematic analysis on a series of statements surrounding professionalism and 772 open-text online survey responses from dental professionals and the public.

Results Professionalism in dentistry and the circumstances where it is brought into question appears to centre around patient trust. Blurriness occurs when we consider how trust is established. Two lines of argument were constructed: patients' trust in the professionalism of their dentist is founded on any behaviour bearing a direct influence on clinical care or that challenges the law; and patients' trust also extends to aspects that reveal the inherent character of the dentist and that can threaten their integrity.

Conclusion We recommend an approach to professionalism that mirrors a dentist's approach to clinical practice: learned and tailored interactions, and judgement and reflection.

Key points

-

Blurriness enters professionalism when we consider how trust is established.

-

Clinical standards are of central importance; however, some view professionalism as a core attribute of an individual's character and thus the boundary between a dentist's life inside and outside the workplace is blurred.

-

A lapse in professionalism is distinct from characteristically unprofessional behaviour.

-

Recommendations are made for implementing learned and tailored interactions with patients and executing judgement and reflection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Professionalism stands as a central component of the education and training of dental professionals.1,2 In the UK for example, the General Dental Council (GDC) places professionalism at the forefront of their regulation with nine key standards they prescribe to govern dental professionals' conduct, performance and ethics.3,4 Given such importance, a shared understanding of the construct is crucial. In recent years, dental education literature has reported endeavours to determine both a clear definition of professionalism and an effective approach to its assessment.1,5,6,7,8

The term professionalism is rarely unaccompanied by other nomenclature, such as integrity, trust, accountability, self-awareness, altruism and communication.4,5,7,9,10 It is apparent that much of the literature has explored what it means to be professional and how professionalism is manifested and expressed,1,2,4,6,7,8,10 while there has been substantially less focus on the boundaries of professionalism and what constitutes unprofessional behaviour or a lapse in professionalism. Many studies also recommend support and guidance to assist dentists in how to learn from their mistakes and to encourage reflective practice;2,8,11 however, the lack of clarity around what constitutes a lapse in professionalism hinders such recommendations. For example, does one unprofessional action or isolated behaviour deem a dentist to be characteristically unprofessional?

Studies that have enhanced our understanding of unprofessional conduct or a lapse in professionalism highlight reports from patients with poor dental experiences: a lack of insight and conscientiousness, an ambivalent attitude, and failure to treat patients with dignity or respect.9,12 Such findings are a valuable contribution but tend either to be limited by their focus on dental students or lack of explicit focus on professionalism, instead centring on negative dental experiences among the public and reasons for dental phobia. These studies also offer little description of the surrounding circumstances and context of patients' experiences. Zilstra-Shaw and colleagues posit that professionalism encompasses not only overt dimensions, such as responsibility and accountability, but also tacit dimensions, such as trustworthiness and self-awareness.2 Similarly, Trathen and Gallagher maintain that professionalism is a concept in which we all have a level of ‘intuitive understanding'.4 Professionalism is a multifaceted, sociological construct,13 comprising individual, interpersonal and societal dimensions;6 consequently, everyone will present their unique interpretation of the expression of professionalism. These societal biases, tacit dimensions and context-dependent features are arguably what has caused professionalism to evade a consensus definition.

This study delves into the views expressed by dental professionals and members of the public on the boundaries between professional and unprofessional conduct and the implications for maintaining professionalism in dentistry. We address the question: what about a dentist's conduct calls their professionalism into question? In exploring this question, we shed light on where the boundary between professional and unprofessional conduct is blurred.

Method

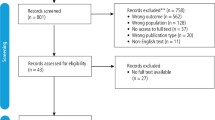

This paper analyses data from a Delphi online survey that was part of a larger mixed-methods study on professionalism in dentistry.14 Invitations to participate in the survey were distributed by key gatekeepers through their relevant networks. Gatekeepers included all the deans of dental schools across the UK, representatives of the Royal Colleges in England, Edinburgh and Glasgow, and a representative at the Committee of Postgraduate Dental Deans and Directors who circulated to all postgraduate deans and directors across the UK. Social media platforms were used to reach a public audience. The survey comprised a series of closed questions where respondents were asked to indicate how professional or unprofessional they regarded various actions or behaviours of dental professionals. Respondents were also invited to provide open-text commentary for explanation or elaboration on their closed responses. This paper focuses primarily on the aggregate results from the closed statements and the open-text responses. The numeric analysis of the two rounds in the survey are described in detail in the full report.14 Respondents were provided with information on the study and indicated agreement to participate by completion and submission of the survey. No individuals were named or identifiable in any data reported. Ethical approval was obtained from the School of Social Sciences at Cardiff University (SREC/3390).

Responses were collected between 13 November and 30 November 2019. All open-text responses were transferred into NVivo (v12) for analysis. Analysis followed a latent thematic approach15 to explore where ambiguity and uncertainty about professionalism occurs and the underlying conditions that lead to a dentist's professionalism to be questioned. Thematic analysis is a method involving the organisation and detailed interpretation of data. The approach involves six steps15 to identifying, analysing and reporting patterns and themes within the dataset: data familiarisation; generation of initial codes; collating codes into potential themes; defining and naming a theme; and producing the report. A latent approach was considered appropriate as the authors sought to go beyond the identification of patterns within the data (semantic thematic analysis) and instead examined the underlying ideas and conceptualisations expressed in the responses.15 Codes were generated by authors SB and ER and discussed and agreed with AB. Final themes were generated by SB and ER and discussed and agreed with authors AB, DC and JC.

Results

Round one of the survey returned 1,069 responses, and round two yielded 665 responses. Respondents represented members of the public and various dental roles, including dentists, dental care professionals (DCPs), dental educators, dental students and dental policymakers/regulators (a breakdown of respondent demographics is provided in the full report).14 Of the respondents, 64% were female, ages spanned from 18-65+ and many reported multiple dental roles. A total of 772 open-text responses, comprising 33,976 words of data, were yielded in response to three questions inviting commentary on professional behaviours (216 responses), unprofessional behaviours (312 responses) and further reflections on professionalism in dentistry (244 responses).

The results demonstrated a higher level of consensus among dental professionals and the public for aspects regarded as professional attributes (consensus for 17/26 relevant statements), than those deemed unprofessional (consensus for 10/27 relevant statements).

All 53 statements were grouped into eight themes, comprising between three and ten statements. The Venn diagram in Figure 1 presents these themes according to themes comprising of only statements that reached consensus (left), only statements that did not reach consensus (right) and statements that both did and did not reach consensus (middle). See the online Supplementary Information for a full breakdown of themes and relevant statements.

Review of these eight groupings of the closed statements (Fig. 1), as well as our latent thematic analysis of open-text survey responses, offered explanation for the placement of these themes within the diagram and where the ambiguity laid. A common overarching explanation for the ambiguity was related to patient trust: professionalism in dentistry and the circumstances where it was brought into question centred around patient trust. The blurriness occurred when respondents described how trust is established. Two lines of argument were constructed: patients' trust in the professionalism of their dentist is founded on any action or behaviour that bears a direct influence on their clinical care or that challenges the law (left side of Venn diagram); and patients' trust in the professionalism of their dentist also extends to aspects that generally do not directly influence their clinical care but reveal the inherent character of the dentist and may pose a threat to the dentist's integrity (left side, but also centre and right side of Venn diagram).

These arguments are presented in turn, followed by a review of processes that build and foster patient trust and thereby maintain professionalism.

Patients' clinical care

One line of argument was that one's professionalism should only constitute actions or behaviours that bear a direct influence on patients' clinical care or that challenge societal law. This argument was built around the themes of ensuring transparency with patients, (not engaging in) discriminatory or illegal behaviour, staying up to date in professional training and development, and treating patients and colleagues with respect and dignity. Participants making this argument urged that professionalism applies exclusively to the workplace setting and a dentist's capacity to fulfil their work duties and provide clinical care, specifically their ‘clinical standards' and ‘clinical skills'. If such standards are adhered to, a dentist's professionalism is maintained:

-

‘The only criteria for deciding if any particular behaviour can be considered as “unprofessional” is whether patient care has been compromised' (dentist)

-

‘What should really matter are the clinical standards. Are dentists treating patients well and giving the right treatment to the patient?' (dental administrator)

Those posing this argument were explicit that dentistry is an occupation, not a lifestyle, arguing that dentists are entitled to a private life, without risk of their professional capacity as a dentist being called into question. One public member expressed ‘I want my dentist to do good dentistry, not to be a paragon of virtue'. Others commented:

-

‘Anything done outside of workplace has nothing to do with do with your “professionalism” at work if you can carry out your job effectively…no one is “professional” 24 hours a day' (dentist)

-

‘The important thing is being able to do the job to the highest technical standards. Other “peripheral” aspects are of no relevance if this simple, primary pre-condition is met' (public).

Some respondents were of the view that the careers of some had been impaired due to factors of no relevance to their role as a dentist and saw this as damaging not only to the dentist, but also to their patients:

-

‘Dentists are often penalised for offences that have very tenuous links to the care that they provide to patients. This is ultimately a disservice to patients as many excellent clinicians are suspended or leave the profession for reasons that should never have entered their work life' (dentist).

Dentists' inherent character and integrity

Those who posed the second line of argument concurred that clinical skills are of central importance, but in contrast, contended that patients' trust in the professionalism of their dentists extends beyond clinical skills and relies also on the inherent character and integrity of the dentist.

These respondents thus adopted a broader interpretation of patients' trust in professionalism and emphasised the importance of wider attributes. This argument was constructed around these themes: presenting as a respectable member of the public; personal appearances; workplace etiquette; and personal life (centre and right side of Venn diagram).

Comments from respondents posing this argument concurred with the paramount importance of maintaining the reputation of dentistry as a ‘profession' (an occupation that involves substantial training and accreditation); however, they believed that upholding this reputation extended beyond clinical duties and required dentists to exhibit ‘integrity and pride in their chosen profession' (public) in all arenas. They posed a wider paradigm of behaviours and attributes not solely confined to the left side of the Venn diagram:

-

‘We have to be extremely aware of our conduct in all fields so the profession is maintained' (dentist)

-

‘Dentists are expected to be respected and trusted individuals' (public).

These respondents emphasised the nature of the dentist-patient relationship as one involving matters of confidentiality and personal information. One dental student stressed that dentists are in a ‘position of trust and power' and patients require confidence their dentist will uphold their integrity. Others remarked:

-

‘It's about trust and trustworthiness' (policymaker/regulator)

-

‘We are dealing with real people of all ages and backgrounds and have access to their personal details. This has to be taken into account' (dentist)

-

‘Patient dignity, beliefs and confidentiality are always of paramount importance' (DCP and dental educator).

The requisites of a dentist's role beyond purely clinical standards consequently led some respondents to a view that workplace and lifestyle were not distinct entities but overlapping settings that influence and blur one another. The two themes ‘presenting as a respectable member of the public' and ‘personal life' constitute behaviours beyond the four walls of the workplace and begin to blur the lines of where professionalism physically starts and ends:

-

‘Individuals should aim to keep a professional manner in both their work and home lives to ensure public confidence in them and in the role they provide' (dentist)

-

‘Being professional should, in my opinion, be more than a 9-5 job. Dentistry can be easily brought into disrepute and hard to regain any lost trust, so how we project ourselves both in and outside of the workplace is very important' (DCP).

Such respondents argued that regardless of the setting, if a dentist's actions or behaviours cloud patient trust, their professionalism is compromised. Such a view is suggestive that professionalism is not an attribute to be switched on and off but is a fundamental component of an individual's character:

-

‘Behaviour is behaviour, whether it is in the surgery, in a public place, or at home. It relates to our personal characteristics, therefore cannot be viewed as location-specific. If you exhibit unprofessional behaviour, it doesn't matter where you are, it speaks to your intrinsic character' (dentist)

-

‘As a healthcare professional, you are never really “off duty”. You have a responsibility to not only your patients and yourself, but your profession, to ensure your patient's trust is preserved at all times' (dentist).

Maintaining integrity and building patient trust

Despite the two distinct arguments, both maintain that professionalism is founded on patient trust. The point at which a dentist's professionalism is called into question appears to be rooted in the ambiguity surrounding how patient trust is established and circumstances that risk a loss in patient trust. We therefore turn to why patient trust presents such ambiguity and how dentists can look to gain and preserve it.

Many comments depicted respondents' views of the influences on patient trust and how patients' experiences and expectations are constructed. Responses were suggestive that which of these two groups a patient falls into is dependent on a myriad of factors, such as ‘age', ‘culture', ‘personal sensitivities' and ‘professional groups':

-

‘Separate individual members of the public may have a completely different perception of what is acceptable or what isn't' (dentist)

-

‘There exists such a full and wide range of personal, individual, professional and social circumstances that impact upon what may be considered “professional” or otherwise' (dentist and dental educator)

-

‘Some people are more open-minded and relaxed than others. It's about using judgement and being respectful, while building a relationship that is based on trust' (DCP).

Good dentistry requires professional judgement and some regarded that this judgement should extend to the dentist's conduct and behaviour surrounding patient interactions:

-

‘Part of professionalism is…accepting that we may need to be different things to different people depending on their own attitudes and pre-conceptions' (dentist and dental educator).

Nonetheless, some respondents emphasised that this professional duty did not need to be sacrificial and personal life did not need to suffer by consequence of chosen career. Instead, it was about applying a level of common sense and judgement:

-

‘There are ways to enjoy life that don't impact on dentistry's reputation' (DCP)

-

‘Being professional is doing what is right by the patient, in their best interest, and having some level of common sense when in a public arena' (dentist).

Some respondents also stressed the importance of the ‘bigger picture', urging that one's professionalism is rarely confined to a single, isolated event. These respondents stressed the importance of dentists' responses to mistakes. A dentist who upon making a mistake, acknowledges the mistake and learns and improves from it, is very different to a dentist who makes a mistake and does not take accountability. These respondents encouraged dentists to adopt a mindful and reflective practice:

-

‘People at all levels make mistakes - it's what we do about/after those mistakes that matters' (dentist/dental educator)

-

‘A reflective professional attitude goes a long way to making choices that show the right intention' (DCP).

Discussion

Much of the literature surrounding professionalism in dentistry has focused on its definition, portrayal and teaching. This study has shifted the focus to the circumstances that lead to a dentist's professionalism to be called into question. Such findings not only complement existing definitions, but further our understanding of the boundaries of professionalism, the breadth of behaviours and actions that influence a judgement of professionalism, and if and how professionalism extends into life beyond the workplace. The limited focus on the role of the dentist is acknowledged and we recommended further research into the implications of these findings on the wider dental team.

The core distinction between the two lines of argument presented here lies in how patient trust is constructed and threatened. Respondents demonstrated key differences in their perceptions of how far professionalism carries, both in terms of skill set (clinical and non-clinical) and location (workplace and public).

We are reliant on individual interpretation that is guided by unique inherent values, morals and perspectives. What is considered ‘unprofessional' will vary from person to person. Some will form their basis of trust purely on the clinical care they receive and the assurance that their dentist complies with societal laws. These components are sufficient to establish and maintain trust. Others will employ a wider definition of trust that extends to the integrity and inherent character of their dentist. This second group will be concerned with dentists' general etiquette in the workplace and how they present themselves as a member of society. They believe that any action or behaviour in any arena has the potential to threaten patient trust and bring a dentist's professionalism into question.

The views presented in this paper also echo the importance of context that has been emphasised elsewhere.1,2,6 It is likely that we do not have an agreed definition of professionalism that can inform day-to-day practice because of inherent variation in personal values: it is not a case of ‘one-size-fits-all' and judgements involve elements of ‘tacit understanding'.2 Professionalism is a sociological construct14 and in dentistry, many definitions employ the word ‘patient'. Brosky and colleagues define professionalism as ‘an image that will promote a successful relationship with the patient'.16 In the medical world, the UK Royal College of Physicians specify character traits for professionalism that ‘underpins the trust the public has'.17 Barrow et al.11 emphasise that one of several justifications for the high standards of professionalism in dentistry is its dependence on trust in the dentist-patient relationship. Different countries and cultures will have different norms and expectations for professional relationships that will influence expectations of professionalism. Both medical and dental reports of professionalism have emphasised that where clinical traits are universal, professional traits are determined by culture, location and organisation of services.18,19 A definition of professionalism therefore can never be prescriptive because, by its very nature and its reliance on patient relationships and trust, it is necessarily subjective.

Our results also indicate that professionalism rarely concerns a single event but relies on the dentist's response to the event and whether they treat it as a learning opportunity. This distinction is supported by results elsewhere that emphasise the importance of reflection on professional conduct.2,7,8,11 We are by no means the first to raise reflection in relation to professionalism but we emphasise the importance of its application beyond purely clinical scenarios. Where this paper has approached professionalism from the perspective of the boundary between professional and unprofessional, we become clearer on the key considerations that should underpin a dentist's professional conduct. Our findings point towards an approach to professionalism that mirrors a dentist's approach to clinical practice. We suggest the following considerations:

-

Learned and tailored interactions - in the UK, for example, continuing professional development is a requirement of all GDC registrants to ensure ongoing development. Such development should also be applied to patient relationships. Each interaction with a patient offers a learning experience that can contribute to the development of that relationship and inform future interactions. Where dental treatments are tailored to the patient's oral needs, interactions should be tailored to their personal needs (for example, social and cultural)

-

Judgement and reflection - reflection is perceived as an aid to development: helping dental professionals learn from experiences in practice. Our results indicate the value in expanding reflective practice, to some extent, beyond the work environment. We encourage dentists to apply judgement to their persona and demeanour and how they wish to portray the image of the dental profession. We suggest the application of a ‘common sense' approach to all activities. To ‘think before acting' provides a simple way to maintain professional behaviour while not feeling the need to be a ‘paragon of virtue'.

Conclusion

We conclude that the focus should be on ‘circumstances' that lead to a dentist's professionalism being called into question. This complements existing definitions and furthers our understanding of the boundaries of professionalism. The transition from professional to unprofessional, and if and how professionalism extends into life beyond the workplace, is a never-ending question. The authors acknowledge the limitation of this paper with the particular focus on the role of the dentist and recommend further research on the wider dental team. The concept of patient trust appears to be where the ambiguity arises and blurs the boundaries between a dentist's life inside and outside the workplace. The results suggest that a ‘lapse' in professionalism and being ‘unprofessional' are not the same. Professionalism rarely concerns a single event but relies on the dentist's response to the event and whether it is treated as a learning opportunity. Educational components of professionalism should be strengthened by applying a similar approach to the oral needs of a patient, namely how a dental professional should interact in a positive way with their patients - a holistic approach to patient-centred care.

References

Zilstra-Shaw S, Robinson P G, Roberts T. Assessing professionalism within dental education; the need for a definition. Eur J Dent Educ 2012; 16: 128-136.

Zilstra-Shaw S, Roberts T E, Robinson P G. Perceptions of professionalism in dentistry - a qualitative study. Br Dent J 2013; 215: e18.

General Dental Council. Standards for the dental team. 2019. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/standards-guidance/standards-and-guidance/standards-for-the-dental-team (accessed February 2023).

Trathen A, Scambler S, Gallagher J E. Professionalism in dentistry: deconstructing common terminology. BDJ Open 2022; 8: 21.

Massella R S. Renewing professionalism in dental education: overcoming the market environment. J Dent Educ 2007; 71: 205-216.

McLoughlin J, Zilstra-Shaw S, Davies J R, Field J C. The Graduating European Dentist - Domain I: Professionalism. Eur J Dent Educ 2017; DOI: 10.1111/eje.12308.

Zilstra-Shaw S, Gorter R C. Dental Professionalism and Professional Behaviour in Practice and Education. In Willumsen T, Lein A P, Gorter R C, Myran L (eds) Oral Health Psychology. pp 305-313. Switzerland: Springer, 2022.

Cserző D, Bullock A, Cowpe J, Bartlett S. Professionalism in the dental practice: perspectives from members of the public, dentists and dental care professionals. Br Dent J 2022; 232: 504-544.

Taylor C L, Grey N J. Professional behaviours demonstrated by undergraduate dental students using an incident reporting system. Br Dent J 2015; 218: 591-596.

Chandarana P V, Hill K B. What makes a good dentist? A pilot study. Dent Update 2014: 41: 156-160.

Barrow H, Bartlett S, Bullock A, Cowpe J. Are the standards of professionalism expected in dentistry justified? Views of dental professionals and the public. Br Dent J 2023; 234: 329-333.

General Dental Council. Professionalism: A Mixed-Methods Research Study. 2020. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/docs/default-source/research/professionalism---a-mixed-methods-research-study.pdf?sfvrsn=3327e7e2_1 (accessed February 2023).

Cope A L, Wood F, Francis N A, Chestnutt I G. Patients' reasons for consulting a GP when experiencing a dental problem: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2018; 68: 877-883.

Irvine D. The performance of doctors. I: professionalism and self-regulation in a changing world. BMJ 1998; 314: 1540-1542.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77-101.

Brosky M E, Keefer O A, Hodges J S, Pesun I J, Cook G. Patient perceptions of professionalism in dentistry. J Dent Educ 2003; 67: 909-915.

Royal College of Physicians. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. Report of a Working Party of the Royal College of Physicians of London. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2005.

Taylor C, Grey N J, Checkland K. Professionalism…it depends where you're standing. Br Dent J 2017; 222: 889-892.

Cruess S R, Cruess R L. Professionalism as a Social Construct: The Evolution of a Concept. J Grad Med Educ 2016; 8: 265-267.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the General Dental Council for commissioning the ADEE project team to undertake the wider review of professionalism in dentistry. We wish to acknowledge the wider ADEE team: Professor Alan Gilmour, Dr Ilona Johnson, Dr Argyro Kavadella, Dr Emma Barnes, Ms Rhiannon Jones and Mr Denis Murphy. We would like to thank the individuals who kindly gave up their time to participate in the online survey for this study. We would also like to extend our thanks to the reviewers who gave their time to provide valuable feedback and recommendations on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sophie Bartlett: methodology; data curation; formal analysis; validation; writing - original draft; and writing - review and editing. Elaine Russ: data curation; formal analysis; validation; writing - reviewing and editing. Alison Bullock: conceptualisation; funding acquisition; methodology; writing - review and editing. Dorottya Czerző: investigation; validation; and writing - review and editing. Jonathan Cowpe: conceptualisation; funding acquisition; methodology; and writing - review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This research was funded by the General Dental Council; however, they were removed from the data collection and analysis procedures. The results reported here do not necessarily reflect the views of the General Dental Council.

Ethical approval was obtained from the School of Social Sciences at Cardiff University (SREC/3390). Respondents were provided with information on the study and indicated agreement to participate by completion and submission of the survey.

No raw data are available. The authors gained ethics approval on the premise that no data would be shared outside the core research team.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2023

About this article

Cite this article

Bartlett, S., Russ, E., Bullock, A. et al. The blurred lines of professionalism in dentistry. Br Dent J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-6592-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-6592-0