Abstract

Introduction Supervised toothbrushing programmes (STPs) are a cost-effective public health intervention, reducing tooth decay and health inequalities in children. However, the uptake of STPs in England is unknown. This study aimed to establish the current provision of STPs across England and summarise the barriers and facilitators to their implementation.

Methods An online survey was sent to dental public health consultants, local authority (LA) oral health leads, and public health practitioners across England. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics. Barriers and facilitators were analysed using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Results Information was received for 141 LAs across England. Approximately half implemented an STP (n = 68/141). Most STPs were commissioned by LAs (n = 44/68) and adopted a targeted approach (n = 54/68). Barriers to implementation were: 1) acquiring funding; 2) poor communication and engagement between LAs, oral health providers and settings; 3) oral health not a priority; 4) logistically challenging to implement; and 5) lack of capacity. Facilitators were: 1) an integrated and mandated public health approach; 2) collaboration and ongoing support between LAs, oral health providers, and settings; 3) clarity of guidance; 4) flexible approach to delivery; 5) adequate available resources; and 6) ownership and empowerment of setting staff.

Conclusion The current provision of STPs is varied, and although there are challenges to their implementation, there are also areas of good practice where these challenges have been overcome.

Key points

-

Identifies the variation in the current provision of supervised toothbrushing programmes across England.

-

Summarises the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of supervised toothbrushing programmes.

-

Provides evidence to support the need for further exploration on the implementation of supervised toothbrushing programmes and the development of efforts to improve their uptake and sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Supervised toothbrushing programmes (STPs) have demonstrated improvements in children's oral health, are cost-effective, and reduce health inequalities.1,2 An STP involves children brushing their teeth supervised by nursery/teaching staff at a convenient timepoint during the day. Programmes in nurseries (children aged 2-4 years old) and schools (Reception and Year 1, age range of 4-6 years old) have been rolled out as part of national oral health promotion programmes in Scotland (ChildSmile)3,4 and Wales (Designed to Smile).5 Evidence from Scotland has shown that STPs cost approximately £15-17 per child per annum and pay for themselves within three years through improvements in children's oral health and reduced need for dental treatment or the need for dental care under general anaesthetic.1 Moreover, for children living in the 20% most deprived areas, there was a significant reduction in dental caries within one year of being enrolled within the programme, while all children showed significant improvements after three years of enrolment.2

In England, health improvement, including oral health improvement, is a statutory responsibility of local authorities (LAs) rather than the NHS.6 In 2017, Public Health England (PHE) conducted a 'stocktake' of LA oral health improvement programmes and found 74 LAs reported having an STP, with most taking place in early years settings, such as nurseries or pre-schools, with children under five years old. However, little information was available about the numbers of children involved in each LA.7 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Department of Health and Social Care proposed that STPs should reach 3-5-year-olds living in the 30% most deprived areas across England by 2022.8 Integrated care systems (ICSs) were established in July 2022; these systems involve partnerships of organisations to deliver integrated health and care services across local areas.9 STPs have been suggested as an intervention that ICSs should consider as part of a targeted oral health prevention programme for children living in the 20% most deprived areas. Moreover, oral health promotion activities are now mandatory in early years settings10 and there are ongoing efforts to see oral health inequalities addressed and STPs implemented nationally, with support from the Office of Health Improvement and Disparities, and NHS England.11,12

Therefore, at present, responsibility for delivering oral health improvement, including toothbrushing programmes, remains with LAs, but uptake and maintenance of these programmes is fragmented, and anecdotally, STPs are also delivered and/or funded by other organisations, including charities and NHS organisations. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on these programmes,12 with not only the closure of schools and nurseries in the first lockdown and then revised guidance issued with amended infection control procedures, but also pressure in these settings owing to staffing issues. So, while there is support to expand STPs across England and potentially opportunities to do so (following changes to the way health and care services are integrated locally), there are also barriers to implementation.

The aim of this survey was to establish the current provision of STPs across England and to summarise the barriers and facilitators to their implementation from the perspective of those involved in commissioning the programmes.

Methods

Ethical approval was provided by the University of Leeds Dental Research Ethics Committee (301121/KGB/338). A survey was developed consisting of 14 closed and open-ended questions, was reviewed by experts in dental public health and oral health promotion and was based on methods used by PHE in their earlier publication.7 The survey included questions about: commissioning organisation of the STP; number of nurseries/schools/childminders and children involved; how the STPs are supported and funded; their longevity; the impact of COVID-19; barriers and facilitators to implementation; and where STPs are targeted to specific areas/groups, the methods used to inform these decisions.

The survey was distributed within an email, accompanied by an information sheet. Upon clicking the link, participants completed the survey on the Online Surveys webpage (https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/). The survey was sent to consultants in dental public health, LA oral health leads, and public health practitioners, identified through professional networks. Consent to participate was implied by completion of the survey.

The survey was opened in January 2022, with three email reminders sent out, and all surveys completed by June 2022.

Data analysis

The quantitative component of the survey was analysed using descriptive statistics. The analysis of the open questions was guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR),13 which is one of the most cited implementation frameworks. This allowed the most prevalent barriers and facilitators to implementation to be identified.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Information was received for 141 LAs across England, with approximately half implementing a STP (n = 68/141; 48%) in their locality (Table 1). The quality and completeness of data were limited. Most of these programmes were commissioned by LAs (n = 44/68) and adopted a targeted approach (n = 54/68). Toothbrushing programmes were primarily targeted by deprivation level, namely the 20-30% most deprived areas, with deprivation level being determined by measures including: the Index of Multiple Deprivation; the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index; eligibility for free school meals; free early learning child spaces; and pupil premium targets. Another key factor determining a targeted approach was the prevalence and severity of dental caries (for example, number of decayed, missing or filled teeth [dmft] and number of hospital admissions for tooth extractions). Other factors influencing targeting of these programmes included specific age groups, special education schools and obesity rates. However, several participants reported the preference to provide a universal offer.

STPs were reported to be delivered in a range of settings, including LA nurseries, private/voluntary/independent (PVI) nurseries, childminders, mainstream primary schools and special education schools. Uptake of STPs across LAs was variable, with the total number of settings delivering supervised toothbrushing per LA ranging between 11-201, covering an age range of 0-19 years old, and being active from one month to 20 years (Table 1). Many participants reported how COVID-19 had impacted on the delivery of STPs, with programmes having to be stopped during the pandemic. As such, at the time of the survey, several areas had not yet re-started implementation of their toothbrushing programmes or were not yet operating at pre-COVID levels. In addition, several participants reported that they had just started to implement an STP with the aspiration to expand or implement in the near future.

Barriers and facilitators to implementation

From the responses to the open questions, data were collected on barriers and facilitators to the implementation of STPs. Guided by the CFIR, these were categorised into overarching themes (Table 2), which are described below.

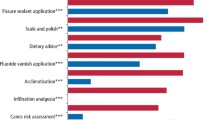

Barriers

Five key barriers to implementation were identified. Barriers to implementation were: 1) acquiring funding; 2) poor communication and engagement between LAs, oral health providers and settings; 3) oral health not a priority; 4) logistically challenging to implement; and 5) lack of capacity. Financial issues were a key barrier with the delivery and storage costs of resources, as well as the difficulty of estimating costs depending on the longevity of the programme, with many expressing the need for external funding. It was reported that there was a lack of engagement from settings, with schools being seen as more difficult to engage with than nurseries. Schools were reported to struggle to prioritise oral health among the multiple demands on them. This was further compounded by the perception of some settings that oral health was not the responsibility of schools. Furthermore, there are logistical issues in relation to the initial set-up and maintenance of the programme, including gaining parental consent. Many settings were said to face physical barriers, such that the layout and facilities were not always able to deliver the programme according to the protocol. Finally, capacity of both the oral health promotion and setting teams to deliver the programme was said to be challenging, given the time required for organisation and training when settings are already stretched.

In addition, almost all the responding LAs reported on how the COVID-19 pandemic had been a significant barrier, with many still not yet operating at pre-COVID levels. There were several reasons reported for the delay, particularly relating to child and staff absences due to illness, a lack of confidence regarding the handling of toothbrushes and assisting the children in a safe way to reduce infection transmission, and difficulties visiting settings to undertake training and quality assurance due to restrictions.

Facilitators

Six key facilitators to implementation were identified: 1) an integrated and mandated public health approach; 2) collaboration and ongoing support between LAs, oral health providers and settings; 3) clarity of guidance; 4) flexible approach to delivery; 5) adequate available resources; and 6) ownership and empowerment of setting staff. The integration of oral health with other health promotion programmes (for example, healthy schools/healthy eating) was felt to be beneficial to the programme's promotion. In addition, many participants felt STPs should be included in the mandated school curriculum and pointed to the recent Ofsted recommendations that settings must ensure the good health of children, including oral health. A key facilitator to the successful implementation of an STP was working in collaboration by adopting a partnership approach between settings, providers, LAs and NHS England. It was stated as important to build collaborations by fostering good communication and relationships, with providers maintaining ongoing support with settings to ensure the long-term continuation of the programme, including providing regular monitoring and feedback. In terms of knowing how to implement the programme, the need for clarity was emphasised, with any protocols being simple, easy to understand and providing a clear plan to follow. Nevertheless, another facilitator was adopting a flexible approach to accommodate the local needs of the setting, including providing robust yet flexible training that fit with the setting's schedule and preferences. In terms of resources, there needs to be the availability of consistent financial, human and physical resources to deliver the programme successfully. It was also posited that a high-quality package of oral health resources for the setting and to send home with the children, as well as the possibility of free resources, would benefit the programme's implementation and impact. Finally, empowering staff to take ownership of the programme and having a key lead in each setting for the overall scheme to drive implementation was seen as key to success. It was reported that it was important that staff were motivated and informed, which could be achieved by emphasising the benefit and ease of the programme.

In addition, many participants were willing to share good practice and their STP resources, including training materials, protocols, quality assurance checklists and local evaluations for the benefit of implementation of STPs in other areas.

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the current provision of STPs across England. Across England, there are different types of LAs, with upper- and lower-tier LAs, with a combined total of 333. During this study, information was received for 141 of the 333 LAs, with approximately half of these implementing an STP. Barriers and facilitators to their implementation were summarised from the perspective of those commissioning the programmes.

Compared to the 'stocktake' undertaken by PHE in 2017, the number of LAs reporting to implement STPs has remained broadly similar (68 LAs in 2022, 74 LAs in 2017), although the responses to the survey suggest the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact in the intervening period. The current survey provides further details for individual LAs of the number of settings and children taking part in the STPs, with wide variation between LAs. For example, the number of settings involved per LA ranged from 11-201, and the number of children involved ranged from 254-8,689. Similar variation was also seen in provision in special education schools. This suggests room for expansion, although the potential for expansion needs to be considered within the remit of government recommendations for STPs to be targeted to children living in the most deprived areas across England. Currently, most of the STPs adopted a targeted approach (n = 54/68), targeting mainly by deprivation level (namely the 20-30% most deprived areas). However, several participants reported the preference to provide a universal offer, particularly in deprived areas of the North of England.

From the responses to the open questions, it was possible to summarise the barriers and facilitators. Some of the themes identified may have been predicted, for example the importance of funding, engagement from settings, staff capacity and hygiene concerns (that is, cross-infection risk and safe handling of toothbrushes). However, other themes, such as priority placed on oral health and the need for resources to facilitate implementing an STP within a LA (or indeed within an individual setting), require further discussion. For example, oral health promotion activities are now mandatory in early years settings,10 which should lend priority to activities such as supervised toothbrushing, although it would appear that some settings are not aware of this standard or choose to achieve it in a different way. In terms of resources, it appears that different LAs have developed their own resources and are willing to share these to facilitate other LAs establishing STPs, and that such resources would be welcomed to overcome barriers around staff training, gaining parental consent, and availability of appropriate quality assurance and infection control protocols. These resources go beyond what is currently available in the Improving oral health toolkit published by PHE in 2016.14 Further research is needed to explore further the barriers and facilitators, not just those experienced by commissioners of STPs, but also those experienced by settings, parents and children, and where possible, to consider solutions to overcome the barriers.

The main limitation of the study was the quality of the data. Issues were noted in terms of the age of children reported to be involved. STPs mainly involved children three years and older, although some LAs reported data using broader age categories, for example 0-5 years. This was due to either piloting new initiatives with younger children in specific settings, or provision being extended due to additional needs. It was also noted by participants that the data provided were an estimate and that numbers of settings and children involved varied, with many noting expressions of interest in expanding STPs back to pre-COVID levels, or had plans for further expansion. This suggests the need for a mechanism to allow data to be updated regularly to monitor the size and reach of STPs and whether any plans for expansion are realised, as currently, there is no unified system for collecting such data. Moreover, it is important to be mindful that the number of LAs a public health consultant has oversight over can vary, with some only having one and others having up to four, thus may only have access to overall estimates rather than LA-specific data. In addition, it is possible that those not operating a toothbrushing programme were reticent to complete the survey. However, we took extensive measures to emphasise that we equally wanted information from LAs that did not or did not currently, being mindful of the impact COVID-19 had on halting STPs, implement toothbrushing programmes. Indeed, several LAs reported that their programmes had temporarily stopped and others reported about their plans to implement in the future. Furthermore, we plan to undertake another survey in the future to capture the changing landscape of implementation and commissioning (for example, ICSs).

Conclusion

In summary, just under half of the LAs that responded currently implement an STP, with the majority being LA-commissioned and targeted by deprivation level. STPs were provided through a variety of delivery models and the number of settings and children participating in STPs ranged from a very small scale to in the thousands. Several barriers to implementation were reported and the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly had a substantial impact on STPs. However, several facilitators to implementation were also reported, with LAs keen to share good practice and resources. Work is currently being undertaken to explore the implementation of STPs further, with the intention of developing efforts to improve their uptake and sustainability.

References

Anopa Y, McMahon A D, Conway D I, Ball G E, McIntosh E, Macpherson L M. Improving Child Oral Health: Cost Analysis of a National Nursery Toothbrushing Programme. PloS One 2015; DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136211.

Kidd J B, McMahon A D, Sherriff A et al. Evaluation of a national complex oral health improvement programme: a population data linkage cohort study in Scotland. BMJ Open 2020; DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038116.

Macpherson L M, Rodgers J, Conway D I. Childsmile after 10 years part 1: background, theory and principles. Dent Update 2019; 46: 113-116.

Macpherson L M, Rodgers J, Conway D I. Childsmile after 10 years part 2: programme development, implementation and evaluation. Dent Update 2019; 46: 238-246.

Iomhair N A, Wilson M, Morgan M. Ten years of Designed to Smile in Wales. BDJ Team 2020; 7: 12-15.

UK Government. Public Health in Local Government. The new public health role of local authorities. 2011. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216708/dh_131904.pdf (accessed July 2023).

UK Government. Oral health improvement programmes commissioned by local authorities. 2017. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/707180/Oral_health_improvement_programmes_commissioned_by_local_authorities.pdf (accessed July 2023).

UK Government. Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s. 2019. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s (accessed July 2023).

NHS England. What are integrated care systems? 2023. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/integratedcare/what-is-integrated-care (accessed July 2023).

UK Government. Statutory framework for the early years foundation stage. Setting the standards for learning, development and care for children from birth to five. 2021. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/974907/EYFS_framework_-_March_2021.pdf (accessed July 2023).

NHS England. Core20PLUS5 - An approach to reducing health inequalities for children and young people. 2023. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/core20plus5/core20plus5-cyp/ (accessed July 2023).

UK Government. COVID-19: guidance for supervised toothbrushing programmes in early years and school settings. 2020. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-supervised-toothbrushing-programmes/covid-19-guidance-for-supervised-toothbrushing-programmes-in-early-years-and-school-settings (accessed July 2023).

Damschroder L J, Aron D C, Keith R E, Kirsh S R, Alexander J A, Lowery J C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009; 4: 50.

UK Government. Improving oral health: A toolkit to support commissioning of supervised toothbrushing programmes in early years and school settings. 2016. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/574835/PHE_supervised_toothbrushing_toolkit.pdf (accessed July 2023).

Acknowledgements

Four of the authors of this paper (Kara Gray-Burrows, Zoe Marshman, Peter F. Day, Kristian Hudson) are supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaborations Yorkshire and Humber (NIHR ARC YH) NIHR200166 (www.arc-yh. nihr.ac.uk). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Thank you to all the local authorities who kindly provided information for this survey.

Funding

This report is independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaborations South West Peninsula and Yorkshire and Humber through the Children's Health and Maternity National Priority Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kara Gray-Burrows, Zoe Marshman and Peter F. Day contributed to the conception and design of the study. All authors contributed to data acquisition. Kara Gray-Burrows, Ellen Lloyd, Kristian Hudson and Sarab El-Yousfi contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the study. Kara Gray-Burrows, Sarab El-Yousfi, Peter F. Day, Zoe Marshman and Kristian Hudson drafted the manuscript, which was critically revised by Kara Gray-Burrows, Zoe Marshman and Peter F. Day. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval was provided by the University of Leeds Dental Research Ethics Committee (301121/KGB/338).

Consent to participate was implied by completion of the survey.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2023

About this article

Cite this article

Gray-Burrows, K., Day, P., El-Yousfi, S. et al. A national survey of supervised toothbrushing programmes in England. Br Dent J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-6182-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-6182-1

This article is cited by

-

BSPD and FDS welcome supervised toothbrushing plan

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

BSPD welcomes supervised toothbrushing plan

BDJ Team (2023)