Abstract

Introduction Despite evidence that public pressure can promote sustainability in various domains (for example, retail and travel), no research has considered the public's attitudes towards sustainability in dentistry.

Methods A questionnaire was developed to measure attitudes towards sustainable dentistry among adults living in the UK and their willingness to make compromises to reduce the impact of their dental treatment on the environment. In total, 344 adults completed the questionnaire that also measured pro-environmental identity and concern, general willingness to make compromises for the environment, and the tendency to engage in ecological behaviours.

Results Participants reported positive attitudes towards sustainable dentistry, and were willing to compromise their time, convenience and durability of their dental treatment, as well as pay more, to reduce the impact of their dental work on the environment. Participants were not willing to compromise their health or the aesthetics of their teeth. There was also evidence that participants' current oral health shaped their attitudes towards sustainable dentistry, such that better oral health was associated with more positive attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry.

Conclusions Given that public pressure can be a significant driver of change, these findings provide valuable insight into the kind of compromises that may be accepted by the public in order to improve the sustainability of dental services.

Key points

-

This is the first study to consider the public's attitudes towards sustainability in dentistry and their willingness to make compromises in order to reduce the impact of their dental treatments on the environment.

-

The findings suggest that people have relatively positive attitudes towards sustainability in dentistry and are willing to make some compromises in order to reduce the impact of their dental treatments on the environment (eg time, convenience, financial) but not others (eg health and aesthetics).

-

The findings also suggest that people's current oral health shapes their attitudes towards sustainable dentistry and their willingness to make compromises, such that better oral health was associated with more positive attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dentistry is a resource-intensive field that has a significant impact on the environment.1 Each year, dental clinics generate significant quantities of plastic waste,2 use gallons of water3 and use substantial amounts of electricity.4 Furthermore, in 2013 to 2014, dental services in England operated by the National Health Service (NHS) produced approximately 675 kilotonnes of greenhouse gas emissions.5 As a result of the Climate Change Act (2008), the NHS is legally required to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050 (a target that has recently been revised to net zero),6 and sustainability is now an important consideration for all healthcare services.

To achieve significant and long-term improvements in the sustainability of dental services, engagement with multiple stakeholders is needed to drive change and reduce the risk of unintended consequences.7,8 For example, if dental services are to significantly reduce their carbon emissions, then policy and legislation are required to set goals and enforce standards (for example, an 80% reduction by 2050),6 manufacturing and supply of dental products and devices must be carried out as sustainably as possible (using data and environmental analysis to guide decision-making),9 and patients and healthcare professionals must be educated in sustainable choices (for example, encourage active travel or use of public transport).10

However, previous research exploring sustainability in dentistry has focused on the role of healthcare providers,11 and no research to date has considered the role of the public in meeting these challenges. This omission is important because research in other contexts has demonstrated that public pressure can be a significant driver of change.12,13 Thus, evaluating the public's attitudes towards sustainability in dentistry may help to understand where changes to practice would be accepted and supported by the public, as well as identifying the potential for public pressure to prompt governments, companies and organisations into action.

However, acting more sustainably often requires that people compromise their time or money, and/or exert more effort to obtain the desired outcome. Furthermore, while research has suggested that people tend to view pro-environmental goals as important, research has also shown that people consider their health as more important.14,15 A key question, therefore, is whether people are still willing to make compromises for the environment when the trade-offs involve factors related to their health and/or the benefits of their dental treatment (for example, the costs, quality, or aesthetics of their treatment).

The present research

The aim of the present research was to explore attitudes towards sustainable dentistry among adults living in the UK and their willingness to make compromises in order to reduce the impact of their dental treatments on the environment. A number of different trade-offs were considered relating to time and convenience, money, functionality, aesthetics and health. These trade-offs were hypothetical in nature such that they aimed to assess what compromises people would be willing to make if given the option. For example, if an environmental assessment revealed that having a longer appointment could reduce the number of single-use plastics used (for example, by allowing the use of reusable instruments that could be sterilised between uses), then would patients be willing to compromise their time to reduce the waste generated from their treatment? Similarly, some of the questions asked participants if they would be willing to compromise their health in order to achieve more sustainable dentistry. Although in practice, a patient's health would never be compromised (and indeed, we did not expect participants to indicate that they would be willing to make this compromise), measuring a range of different trade-offs allowed us to compare people's willingness to make different compromises and empirically test the hypothesis that people prioritise their health.14,15

The research also sought to identify factors that were associated with participants' attitudes and willingness to make compromises for more sustainable dentistry (for example, sample demographics, use of dental services, individual differences in pro-environmental attitudes). Thus, there were two overarching research questions for the present research:

-

1.

To what extent do people have positive attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry and to what extent are they willing to make compromises to achieve it?

-

2.

What factors are associated with peoples' attitudes towards, and willingness to make compromises for, more sustainable dentistry?

Materials and methods

Study design

An online questionnaire, distributed via the survey software Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com/), was used to measure participants' attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry and their willingness to make compromises to reduce the impact of their dentistry on the environment, along with potentially related constructs - such as pro-environmental identity and concern, willingness to make sacrifices for the environment more generally, and the tendency to engage in pro-environmental behaviour in other domains. There were two versions of the questionnaire: i) a short version consisting of only the measures of demographics and attitudes towards, and willingness to make compromises for, sustainable dentistry; and ii) a full version comprising all measures. Participants recruited in private dental practices were asked to complete the short version of the questionnaire so that they had time to complete the questionnaire before or shortly after their appointment. Participants recruited via other means completed the full questionnaire. Data were collected over six months between August 2020 and February 2021, and ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee in the Department of Psychology at The University of Sheffield (March 2020, #033450).

Recruitment and participant characteristics

Three strategies were used to recruit participants: i) staff and dentists at four private dental practices in the UK asked patients who were attending their dental appointment whether they would be interested in taking part in a research study and (if so) sent them a link to the online questionnaire; ii) an advert was placed on Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/), an online participant recruitment platform for scientific research; and iii) adverts were placed on the social media accounts (for example, Facebook and Twitter) of members of the research team. Participants recruited via Prolific received £2.50 for completion of the questionnaire, whereas participants recruited in dental practices or via social media had the option to enter a prize draw to win a £20 Amazon voucher. To be eligible to participate, individuals needed to be aged 18 or over and be currently living in the UK.

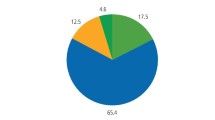

Table 1 displays the demographic and dental characteristics of the 344 participants who were recruited. Participants were aged between 18 and 77 years (M = 33.0; SD = 12.1) and were predominantly female (70%) and White British (84%). Most participants described themselves as registered with a dental practice (82%), had visited a dentist within the last 12 months (69%) and attended the dentist regularly for routine check-ups (59%). On average, participants rated their oral health as good (M = 3.7 out of 5; SD = 0.8) and the participants who said that they were currently experiencing pain with their teeth (11%) rated that pain as mild (M = 3.8 out of 10; SD = 2.1).

Measures and procedure

Participants were invited to take part in a study exploring people's views towards sustainable dentistry. If participants were interested in taking part, then they were asked to click on a link to the online questionnaire, which first presented information about the study, followed by a consent form. Participants were then asked to provide demographic information, including their age, gender and ethnicity, along with questions regarding how frequently they visited the dentist, when their last visit to the dentist was and how they paid for their dental treatment. Participants were also asked to indicate whether their teeth were currently causing them pain (and if so, how they would rate the pain on a ten-point scale, where ten is the worst pain imaginable) and how they would rate their general oral health (on a five-point scale ranging from 'very poor' to 'very good'). Following this, participants were asked to complete measures of pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours. Table 2 provides an overview of the measures used in the present research. The measures were presented in a random order and, unless stated otherwise, all items were assessed on five-point Likert scales ranging from 'strongly disagree' to 'strongly agree'. A list of the questionnaire items that have not been used in previous research (that is, items to assess participants' attitudes towards sustainable dentistry, and willingness to make compromises to reduce the impact of their dental treatment on the environment) are provided in Appendix 1.

Approach to analyses

The data were analysed in two stages. First, descriptive statistics were used to explore participants' attitudes towards sustainable dentistry and their willingness to make compromises to achieve it. Second, the relationships between the demographic variables (for example, age, gender), use of dental services (for example, frequency of dental visits), and individual differences (for example, pro-environmental identity and concern) and participants' attitudes and willingness to make compromises for more sustainable dentistry were explored using correlations, t-tests, and (M)ANOVAs as appropriate. The analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 25), and the anonymised data and syntax relating to the analyses can be found online (https://tinyurl.com/attdentistry) The full statistics (for example, p values, effect sizes) from all analyses can be found in Appendix 2.

Results

To what extent do participants have positive attitudes towards sustainable dentistry and are willing to make compromises to achieve it?

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for each study variable. Overall, participants reported relatively positive attitudes towards sustainability in dentistry (M = 3.8, 95% CI [3.7, 3.9]) and were moderately willing to compromise time and convenience (M = 3.7, 95% CI [3.6, 3.8]), the durability of their dental treatments (M = 3.2, 95% CI [3.1, 3.3]) and to pay more (M = 3.1, 95% CI [3.1, 3.3]) for more sustainable dentistry. However, it was less clear whether participants were willing to compromise the appearance of their teeth (M = 2.8, 95% CI [2.7, 2.9] or their oral health (M = 2.2, 95% CI [2.2, 2.3]).

There was a significant difference in the extent to which participants were willing to make different compromises for more sustainable dentistry, F(3.43, 1165.68) = 240.14, p <0.001, ηp2 = 0.41. Participants were significantly more willing to compromise their time and convenience than they were to pay more or compromise the durability of their dental treatments. Participants were least willing to accept compromises related to the appearance or health of their teeth. All comparisons were significant at p <0.001, except for the comparison between participants' willingness to pay more and their willingness to compromise the durability of their dental treatments (p = 1.00).

Factors associated with participants' attitudes towards, and willingness to make compromises for, sustainable dentistry

Demographics

Participants' ethnicity, level of education and employment status were not found to be associated with their attitudes towards, or willingness to make compromises for, sustainable dentistry (p values >0.05). There were, however, significant differences according to age and gender, such that older participants were less willing to compromise their time and convenience than younger participants (r = -0.12, p = 0.029), and women had more positive attitudes towards sustainable dentistry (M = 3.9, 95% CI [3.8, 3.9]) compared to men (M = 3.6, 95% CI [3.5, 3.8]; t(169.75) = -2.08, p = 0.039, d = 0.26). Men and women did not differ in their willingness to make compromises for more sustainable dentistry (p values >0.05).

Given that our sample was recruited using three different methods (that is, Prolific, social media, or approached in a dental clinic), we explored whether participants' attitudes and willingness to make compromises varied according to how participants were recruited. There were significant differences between the methods of recruitment in participants' attitudes towards sustainable dentistry (F[2,338] = 6.78, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04) and willingness to pay more for more sustainable dentistry (F[2,338] = 10.76, p <0.001, ηp2 = 0.06). Pairwise comparisons (with Bonferroni adjustment) revealed that participants who were recruited via dental practices had more positive attitudes towards sustainable dentistry (M = 4.3, 95% CI [4.0, 4.5]) than participants who were recruited via Prolific (M = 3.7, 95% CI [3.6, 3.8]; p = 0.006). Participants who were recruited via dental practices were also more willing to pay more to reduce the impact of their dentistry on the environment (M = 3.8; 95% CI [3.5, 4.1]) than participants who were recruited from Prolific (M = 3.1; 95% CI [3.0, 3.2]; p = 0.001).

Use of dental services

Participants who were registered with a dentist had more positive attitudes towards sustainable dentistry (M = 3.8, 95% CI [3.7, 3.9]) than participants who were not registered with a dentist (M = 3.6, 95% CI [3.4, 3.8]; t(342) = 2.00, p = 0.046, d = -0.28). Registration status was not associated with the extent to which participants were willing to make compromises to reduce the impact of their dentistry on the environment (p values >0.05). However, the frequency with which participants visited the dentist was found to be associated with the extent to which participants were willing to pay more to reduce the impact of their dentistry on the environment (t[339] = -3.04, p = 0.003, d = 0.34). Participants who visited the dentist regularly for routine check-ups were more willing to pay more to reduce the impact of their dentistry (M = 3.3, 95% CI [3.2, 3.4]) than participants who only visited the dentist when they had a dental problem (M = 3.0, 95% CI [2.8, 3.1]). Given that only two participants reported that they never went to the dentist (see Table 2), this group was omitted from the analyses. The frequency with which participants visited the dentist was not associated with their attitudes towards sustainable dentistry, nor their willingness to compromise their time and convenience nor the health and aesthetics of their teeth (p values >0.05). There was no difference in participants' attitudes nor willingness to make compromises for more sustainable dentistry according to whether participants receive their dental treatments via the NHS or through a private provider (p values >0.05).

Correlation analyses indicated that participants' self-rated oral health was positively associated with their attitudes towards sustainable dentistry, such that better oral health was associated with more positive attitudes (r = 0.11, p = 0.042). Participants' oral health was not associated with their willingness to make compromises for more sustainable dentistry (p values >0.05). There was no difference in participants' attitudes towards sustainable dentistry nor their willingness to make compromises to reduce the impact of their dentistry according to whether or not participants were experiencing pain or discomfort with their teeth (p values >0.05)

Individual differences

Table 4 presents the bivariate correlations between the study variables. The correlations were all significant, except for the correlation between participants' ecological worldview (that is, scores on the NEP) and their willingness to compromise the health of their teeth for more sustainable dentistry (r = -0.03, p = 0.571). Attitudes towards sustainable dentistry were positively associated with participants' willingness to compromise their time and convenience (r = 0.68), money (r = 0.53) and the durability of their dental treatments (r = 0.52). Attitudes towards sustainable dentistry were also positively associated with participants' willingness to compromise the aesthetics (r = 0.40) and health of their teeth (r = 0.29), although the size of these relationships were smaller. Together, these findings suggest that (as expected) more positive attitudes are associated with greater willingness to make compromises to reduce the impact of dentistry on the environment.

Attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry were also positively associated with measures of pro-environmental identity and concern (r = 0.64 and 0.68, respectively). Similarly, willingness to make sacrifices for the environment more generally was also associated with participants' willingness to make compromises for more sustainable dentistry, although the correlation with willingness to compromise health (r = 0.49) was smaller than the correlations with other trade-offs (r values range from 0.56 to 0.69). Lastly, whether participants engaged in pro-environmental behaviour in other domains (for example, when buying groceries) was also positively associated with participants' attitudes towards sustainable dentistry and participants' willingness to make compromises for more sustainable dentistry (r values range from 0.26 to 0.56).

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to explore attitudes towards sustainable dentistry among adults living in the UK and their willingness to make compromises in order to reduce the impact of their dental treatments on the environment. Participants in the present study reported positive attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry and were willing to compromise their time, convenience and the durability of their dental treatment in order to reduce the impact of their dental treatments on the environment. They were also willing to pay more if it meant that their dentistry was more sustainable. However, participants were less willing to compromise the appearance or health of their teeth, which is consistent with previous research indicating that, while people consider environmental goals important, they consider their health as more important.14,15

We also found that more positive attitudes towards sustainable dentistry were associated with greater willingness to make compromises in order to reduce the impact of dental treatments on the environment, with the size of these correlations ranging from medium to large. This is consistent with previous research and models of behaviour (for example, Theory of Planned Behaviour,24 Prototype Willingness Model)25 which suggest that people's attitudes are a key (albeit indirect) predictor of subsequent behaviour and suggest that interventions which focus on increasing positive attitudes may subsequently prompt people to be more willing to make greater compromises for the environment. In particular, research has shown that promoting specific attitudes (for example, towards sustainable dentistry) is the strongest predictor of subsequent behaviour (termed the principle of compatibility),26 so interventions might want to focus on promoting positive attitudes towards sustainable dentistry, rather than sustainability more generally.

The present study also explored factors that may be associated with (and thus help to understand) participants' attitudes towards, and willingness to make compromises for, more sustainable dentistry. Of the sample demographics, age and gender were found to be associated with participants' attitudes and willingness to make compromises. Specifically, younger participants were more willing to compromise their time and convenience in order to reduce the impact of their dental treatment on the environment, and women had more positive attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry. These findings are consistent with previous research that found that younger generations are more pro-environmentally driven27 and research that has pointed towards an 'eco gender gap', where men report being less committed to maintaining an eco-friendly lifestyle than women.28

In terms of participants' use of dental services, we found that participants who were registered with a dentist had more positive attitudes towards sustainable dentistry than participants who were not registered with a dentist, and participants who visited the dentist regularly for routine check-ups were more willing to pay more to reduce the impact of their dental treatments than participants who only visited the dentist when they had a dental problem. Similarly, participants who were recruited in a dental clinic had more positive attitudes and were more willing to pay more to reduce the impact of their dental treatments on the environment than participants who were recruited online. There are a number of possible explanations for these findings. It could be that people who are more engaged with dental services (that is, are registered with a dentist and visit the dentist more frequently) are more aware of the impact of dentistry on the environment (for example, because they have recently seen the high quantities of single-use plastics used during their appointment). However, it would be interesting to explore whether - and to what extent - people are aware of the materials that are used in their treatment.

Alternatively, it could be that people who are registered with a dentist and attend regularly for check-ups have better oral health and are therefore more willing to engage in sustainability efforts because doing so is likely to be less costly for them personally. In support of this explanation, we also found that better oral health was associated with more positive attitudes towards sustainable dentistry, and further exploratory analyses of our data confirmed that people who were registered with a dentist and attended the dentist more regularly also had better oral health. Taken together, these findings may suggest that if people have good (oral) health, then they are more willing to engage in sustainability efforts. However, if people have poor (oral) health, then they prioritise their health and are less willing to engage in sustainability efforts. Although these hypotheses would need to be empirically tested, they would support other arguments that good oral health can act as a driver towards more sustainable dentistry. For example, better oral health would lead to fewer appointments, fewer patient journeys, and less need for materials and intervention.29

Finally, whether participants engaged in pro-environmental behaviour in other domains (for example, recycling at home) was also positively associated with participants' attitudes towards sustainable dentistry and their willingness to make compromises for more sustainable dentistry. These findings support psychological theories which suggest that people need consistency in their attitudes, beliefs and behaviours (for example, Theory of Cognitive Dissonance)30 and supports research which has shown that pro-environmental behaviours tend to 'spill over' into other pro-environmental behaviours (for example, buying organic produce in the supermarket can lead to using less water at home).31

Limitations and future directions

This is the first study to assess the public's attitudes towards sustainability in dentistry in the UK and provides useful insights into the types of compromises that people may be willing to make in order to reduce the impact of their dental treatments on the environment. However, the study is not without some limitations. For example, although we sampled the views of around 350 individuals, the composition of the sample may limit the generalisability of the findings. For example, the majority of the sample were female, White British and currently living in the UK. We only recruited adults who were currently living in the UK because previous research has indicated that there are cross-cultural differences in people's pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours,32 and the aim of the present research was to examine the attitudes and opinions of adults in the UK. However, the methods and tools used in the present research could be used to investigate and compare attitudes towards sustainable dentistry in other contexts and cultures. It is also worth noting that the present study did not measure household income nor socioeconomic status. These variables are potentially important, particularly as we are asking people whether or not they may be willing to make financial compromises to reduce the impact of their dental treatments on the environment.

The present study also assessed participants' willingness to make compromises, as opposed to actual behaviour; in part, because there is currently little choice for the public when it comes to reducing the impact of their dental treatments on the environment. However, understanding willingness is important as it can point to what people are likely to do if given the option - indeed, research has shown that willingness is a key predictor of behaviour in the future.33 Furthermore, given that the trade-offs that were examined in the present research were largely hypothetical in nature, future research may want to use environmental assessment (for example, Life Cycle Assessment),34 in order to inform which types of compromises would have a beneficial impact on the sustainability of dental services. Such research would inform what changes should be made, while our research can inform whether such changes would likely be accepted by the public.

Finally, the timing of the data collection for this study also situates the findings in a unique context. The data were collected in August 2020, approximately five months after the UK initiated a national lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. During this time, public health was prioritised, along with the economic and social impacts of COVID-19, and concerns regarding the environment were largely sidelined.35 As a result, the UK saw a significant increase in single-use plastics in both healthcare and beyond (for example, face masks and shields in retail)36 and many efforts to promote sustainability in other domains were abandoned (for example, Starbucks refused reusable coffee cups).37 In this context, it is promising that participants' attitudes towards improving the sustainability of dental services was largely positive in the present study; however, future research may want to consider whether and how participants' attitudes towards sustainable dentistry change over time.

Conclusion

This is the first study to assess the public's attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry in the UK, and assess the extent to which people are willing to make personal compromises in order to reduce the impact of their dental treatments on the environment. Overall, we found that people have positive attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry and that people are willing to make certain compromises (for example, time, convenience and paying more), but not others (for example, health and aesthetics). The findings also suggest that people's current health may play an important role in their attitudes towards sustainable dentistry and their willingness to make compromises, such that only people who are in good health are willing to engage in sustainability efforts.

References

Mulimani P. Green dentistry: the art and science of sustainable practice. Br Dent J 2017; 222: 954-961.

Martin N, Mulligan S, Fuzesi P et al. Waste plastics in clinical environments: a multi-disciplinary challenge. In Plastics Research and Innovation Fund Conference. pp 86-91. Sheffield: University of Sheffield, 2020. Available at https://www.ukcpn.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/PRIF-Conference-Brochure-Final-1.pdf (accessed December 2021).

Eco Dentistry Association. Dental office waste and pollution. Available at https://ecodentistry.org/green-dentistry/what-is-green-dentistry/save-water/conventional-suction-systems/ (accessed December 2021).

Duane B, Harford S, Steinbach I et al. Environmentally sustainable dentistry: energy use within the dental practice. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 367-373.

Public Health England and Centre for Sustainable Healthcare. Carbon modelling within dentistry: Towards a sustainable future. 2018. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/724777/Carbon_modelling_within_dentistry.pdf (accessed December 2021).

NHS England and NHS Improvement. Delivering a 'net zero' national health service. 2020. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2020/10/delivering-a-net-zero-national-health-service.pdf (accessed December 2021).

Duane B, Stancliffe R, Miller F A, Sherman J, Pasdeki-Clewer E. Sustainability in dentistry: a multifaceted approach needed. J Dent Res 2020; 99: 998-1003.

Ryan-Fogarty Y, O'Regan B, Moles R. Greening healthcare: systematic implementation of environmental programmes in a university teaching hospital. J Clean Prod 2016; 126: 248-259.

Duane B, Ramasubbu D, Harford S et al. Environmental sustainability and procurement: purchasing products for the dental setting. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 453-458.

Duane B, Steinbach I, Ramasubbu D et al. Environmental sustainability and travel within the dental practice. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 525-530.

Khanna S S, Dhaimade P A. Green dentistry: a systematic review of ecological dental practices. Environ Dev Sustain 2019; 21: 2599-2618.

Baron D P, Harjoto M A, Jo H. The economics and politics of corporate social performance. Bus Polit 2011; 13: 1-46.

Dauvergne P. The power of environmental norms: marine plastic pollution and the politics of microbeads. Environ Polit 2018; 27: 579-597.

YouGov UK. The environment is once again a top three priority for the British public. 2021. Available at https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2021/06/04/environment-once-again-top-three-priority-british- (accessed July 2021).

Lorenzoni I, Nicholson-Cole S, Whitmarsh L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob Environ Change 2007; 17: 445-459.

Whitmarsh L, O'Neill S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J Environ Psychol 2010; 30: 305-314.

Ellen P S. Do we know what we need to know? Objective and subjective knowledge effects on pro-ecological behaviours. J Bus Res 1994; 30: 43-52.

Dunlap R E, Van Liere K D. The "new environmental paradigm". J Environ Educ 1978; 9: 10-19.

Dunlap R E, Liere K V, Mertig A, Jones R E. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J Soc Issue 2000; 56: 425-442.

Davis J L, Le B, Coy A E. Building a model of commitment to the natural environment to predict ecological behaviour and willingness to sacrifice. J Environ Psychol 2011; 31: 257-265.

World Values Survey (WVS). World Values Survey: the World's Most Comprehensive Investigation of Political and Sociocultural Change. 2009. Available at https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp (accessed December 2021).

Vesely S, Klöckner C A, Brick C. Pro-environmental behaviour as a signal of cooperativeness: Evidence from a social dilemma experiment. J Environ Psychol 2020; 67: 101362.

Peng I-C. The DECIDE scale: development of a dentistry-related environmental concern scale. Sheffield: University of Sheffield, 2020. Dissertation.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991; 50: 179-211.

Gibbons F X, Stock M L, Gerrard M. The prototype-willingness model. Wiley Encyclop Health Psychol 2020; DOI: 10.1002/9781119057840.ch102.

Siegel J T, Navarro M A, Tan C N, Hyde M K. Attitude-behaviour consistency, the principle of compatibility, and organ donation: A classic innovation. Health Psychol 2014; 33: 1084-1091.

Yamane T, Kaneko S. Is the younger generation a driving force toward achieving the sustainable development goals? Survey experiments. J Clean Prod 2021; 10: 125932.

Mintel. The Eco Gender Gap: 71% of Women Try to Live More Ethically, Compared to 59% of Men. 2018. Available at https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/socialand-lifestyle/the-eco-gender-gap-71-of-women-try-to-live-more-ethically-compared-to-59-of-men (accessed December 2021).

Martin N, Mulligan S. Environmental sustainability through good-quality oral healthcare. Int Dent J 2021; 72: 26-30.

Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1957.

Truelove H B, Carrico A R, Weber E U, Raimi K T, Vandenbergh M P. Positive and negative spillover of pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and theoretical framework. Glob Environ Change 2014; 29: 127-138.

European Union. Special Eurobarometer 501: Attitudes of European Citizens towards the Environment. 2020. Available at https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/9a97b30e-15cb-11ec-b4fe-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed December 2021).

Hukkelberg S S, Dykstra J L. Using the Prototype/Willingness model to predict smoking behaviour among Norwegian adolescents. Addict Behav 2009; 34: 270-276.

Borglin L, Pekarski S, Saget S, Duane B. The life cycle analysis of a dental examination: Quantifying the environmental burden of an examination in a hypothetical dental practice. Community Dent Oral 2021; 49: 581-593.

Saadat S, Rawtani D, Hussain C M. Environmental perspective of COVID-19. Sci Tot Environ 2020; 728: 138870.

Silva A L, Prata J C, Walker T R et al. Increased plastic pollution due to COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and recommendations. Chem Eng Sci 2021; 405: 126683.

Evans A. Coronavirus: Starbucks bans reusable cups to help tackle spread. 2020. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-51767092 (accessed December 2021).

Funding

This research was funded by the Plastics Research and Innovation Fund (PRIF), delivered via the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC; EP/S025278/1), and the Smart Sustainable Plastics Packaging Challenge (SSPP), delivered via the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC; NE/V010638/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed towards the design of the study. H. M. Baird and S. Mulligan collected the data, which was analysed by H. M. Baird. All authors contributed to writing up the research and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2022

About this article

Cite this article

Baird, H., Mulligan, S., Webb, T. et al. Exploring attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry among adults living in the UK. Br Dent J 233, 333–342 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4910-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4910-6

This article is cited by

-

Is cloud-based software as sustainable as we think?

BDJ In Practice (2023)

-

Powerful disinfectant properties

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

The ECODENT Model for Enhancing Pro-environmental Behaviors in Dentists

Circular Economy and Sustainability (2023)