Abstract

This paper forms part of a series of papers, seven in total, which have been requested by colleagues to help them as clinicians understand sustainability as it relates to dentistry. This paper focuses on biodiversity and how the dental team can become more sustainable. It is hoped that these series of papers stimulate interest, debate and discussion and, ultimately, influence dentistry to become more environmentally sustainable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Highlights how human wellbeing depends on the health of the biosphere of the planet.

-

Suggests many dental practices have outside areas that could be used to encourage biodiversity, provide benefits such as cleaner air and water, and create a more attractive property.

-

Provides tips on how to encourage biodiversity, such as creating wild areas and incorporating building structures like green roofs, green walls and roof eaves.

Introduction

Human wellbeing depends very much on the interacting web of living species; if healthcare providers are truly concerned about human health they also need to concern themselves with the health of the planet.1 Awareness of the links between quality of environment, climate change and human health is increasing. However, to date, much of the limited research on dentistry and environmental sustainability has focused on carbon dioxide emissions and the impact of amalgam.2,3,4 Papers two to five within this series on sustainability within the dental practice focus directly and/or indirectly on these emissions.5,6,7,8 Even though the link between dentistry and encouraging biodiversity seems weak, there is a significant amount the dental team can contribute to the health of the local environment and, in doing so, to the overall health of the people they care for.

Biodiversity means the variability among living organisms and the ecological communities of which they are part.9 In 2017, Ceballos et al. published a review highlighting the significant decline in populations of most global vertebrate species, predominately due to a reduction in their habitat, which ultimately effects the ecosystems human society depends on.10 Around 30% of land vertebrates (reptiles, birds and amphibians) are losing population and habitat.1 Within the UK, 15% of around 8,000 species assessed are facing extinction, with renowned naturalist David Attenborough suggesting that the UK has lost more nature long-term than the global average, making the UK one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world.11 Biodiversity declines are being recorded across all food chains. Between the 1950s and 2013, insect numbers in protected areas of Germany have plummeted 80%, likely due to the widespread use of insecticides and habitat loss in the surrounding countryside. Similar losses in bee- and insect-pollinated plant diversity are being recorded in the UK and the Netherlands.12,13,14,15

Scientists provide many reasons for the reduction in the world's insect populations, notably the use of pesticides, the spread of monoculture crops, urbanisation and habitat destruction. Because we rely on insects for a wide range of ecosystem services, the significant drop in insect populations we are seeing could be disastrous as it impacts on the pollination of crops and wild plants, control of pest species, decomposition of waste, and as food sources for other animals.14,16,17,18

Within the overall NHS, there is estate land surrounding NHS premises. The NHS Forest has over 150 sites across England coordinated by the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare to improve public health and wellbeing, encourage greater social cohesion, and help initiate projects to use new and existing woodland for food, crops, reflective and exercise space, and to encourage biodiversity.19 There is considerable evidence that green space can improve health across a number of different dimensions including mental and physical health (in particular obesity, cardiovascular and respiratory health). The evidence is weak but growing, and is reviewed in a recent paper by Markevych et al.20

There were 46,000 dental practitioners registered in the UK during the period 2010-2017.21 Although there is no official information on land associated with NHS dental practices, it is expected that a number of dental practices within the UK and Ireland have outside areas that can be used more effectively to encourage biodiversity. This paper is written mainly for dental practices with some external space, whether it be a large garden or a small lawn and provides advice on how to do this.

Importance of urban areas for biodiversity

Traditionally, urban spaces were considered significantly less important for maintaining the natural environment than rural areas. However, biodiversity can be high in urban areas too, providing opportunities for rich and varied plant and animal life to thrive.22,23 Ensuring there is high-quality green space and biodiversity within towns and cities also provides benefits such as cleaner air and water and more attractive properties.24 As urban areas expand and rural areas decline, the value of urban biodiversity is increasing.25,26 From a sustainability perspective and within the dental setting, urban environments are divided into green space, grey space and brownsites.24 Bearing in mind the relevance to dental practices, only green and grey spaces will be discussed in this paper.

Green space

Green space within a city describes everywhere vegetation grows. Within a dental setting, the term describes any green area surrounding a dental practice.24 Green infrastructure encompasses the entire working landscape and has a crucial role to play in improving air quality, providing protection against both floods and heat in the summer, and helping control pollution.27

Gardens are significant contributors to urban biodiversity and can reduce urban fragmentation (the loss of connection between green space).28,29,30 This connectivity increases the area of continuous habitat and diversity of natural or semi-natural habitats that support native plants and animals.24,31 There is also growing evidence of the psychological benefits of seeing and caring for plants.32

By contributing to the wider network of green space, gardens can help provide a habitat for a variety of wildlife including insects, birds and smaller mammals.28 Gardens also contribute to a number of beneficial processes including regulating water drainage via their porous surfaces and reducing the effects of strong winds.33 There are a number of types of green space such as lawns, plants, left-aside areas, water, and simple structures for insects.

Lawns

In reality, many gardens may be poorly equipped to perform these functions. In many countries there is still a tradition of having neat and tidy gardens, mown lawns and clean concrete areas, reliant on frequent weeding and application of insecticides. However, weed species such as clover and dandelion, are important sources of pollen for a wide range of beneficial insects, such as bees, that are also harmed by insecticides.34 A carefully manicured lawn is very poor from a biodiversity perspective. The invertebrate conservation trust Buglife suggest that mown lawns should at least have a wild corner to attract wild flowers and insects.35 The frequency of lawn cutting should be reduced to improve biodiversity. Wild lawns should only be cut occasionally and infrequently fertilised, as few herbaceous species can cope with the disturbance of grass mowing.36

Plant type

When choosing plant types for a sustainable garden, the dental team should consider the value of plants to optimise conditions and allow for the reproduction of species; for example, by providing resources for bees and other pollinating insects.34 There is not a list of plants per se that will provide this function, but a biodiverse garden is one that produces a diverse range of flowers that bloom at different times of the year.26,36

Native plants are the ideal. Depending on which country the dental practice is based in, herbs, fruits and vegetables may all produce valuable flowers. Fruit and herbs are all attractive to insects; for example, berries, melon, squash, cucumber, blossoming trees, mint, rosemary and sage.37 Non-scented commercial plant types, such as hybrid rose bushes, are not as attractive or beneficial to insects. Herbaceous communities, such as meadows and pastures, have very high diversity and can be successfully replicated in small urban areas.29

The use of pesticides should be avoided. A recent report by the United Nations highlights the dangers of pesticides and supports the use of other more biologically sustainable options.38 When there is a real need to resort to pesticides, they should be used in a specifically targeted manner, for example to control invasive plants.

Left-aside areas

This strategy can be combined with left-aside areas, which can include piles of fallen leaves, dry wood and branches. These can look more conventionally attractive with careful stacking and arrangement. Woodpiles and fallen leaves within a garden provide resources for fungi, lichen and moss to flourish and are ideal habitats for insects, such as ground beetles, which act as pest managers of slugs.33

A moderate level of management is needed to prevent these areas becoming totally overgrown by a species that reduces diversity but, for most of the year, the area would be very low maintenance. These areas provide nesting space for bumblebee colonies and overwintering shelter for a range of species, including hedgehogs.39,40,41 Set-aside areas can also double as a location for a compost heap. If there is sufficient external space within a dental practice, tree canopies dramatically increase the volume of habitat space for many bird, insect and reptile species.

Water

There are various other elements the dental team could introduce into an outside area to improve sustainability. Areas of standing water, such as containers filled with water or ponds, can help attract insects, birds and amphibians. Larger areas provide habitats for frogs, toads and newts to live and reproduce.42

Simple structures for insects and reptiles

Habitats for insects, including solitary bees, can be encouraged by making insect homes using bamboo canes tied together. If a box is used to hold the canes, it should be turned on its side and hung from a tree or a post at eye level, sheltered from the rain. Such 'bee hotels' provide valuable nesting space,43 but in some situations could lead to increased disease-spread or exploitation by invasive species (for more information check with your local insect conservation charity).44 Small reptiles and slowworms can be accommodated by placing strong canvas or other natural material, like compost heaps/piles of mown grass, in a corner of the garden.33 Piles of stones and bricks provide an ideal environment for reptiles. Practices could also place bird food in bird feeders during the winter months.

Grey space

Grey space within a town/city is the non-green elements, including buildings, footpaths and roads. There are a number of ways these areas can be adapted to reduce the impact of growing urban sprawl on our environment, including green roofs, green walls, balconies, roof eaves and living ground coverings.45

Green roof

A green roof, also known as a living roof, brown roof or biodiverse roof, is a relatively inexpensive option to improve the sustainability of a building. Green roofs are designed to allow growth of different vegetations.45 Creating a green roof can be as simple as rolling out matting or wildflower turf, or can be more specialised; websites such as Blackdown46 offer a full range of options. These roofs aim to replicate a natural growing environment for plants without being overly heavy and can also be used on smaller structures, such as sheds. By planting a diverse range of plants, they are beneficial to urban biodiversity.29 The roof structure can be quite low maintenance, especially if stress-tolerant plant species are used.47 Green roofs help mitigate the urban heat island effect (an urban area is significantly warmer than the surrounding countryside), and help with both energy conversation and storm water management.48,49

Green walls

Green walls are vertical systems of green foliage. They can be found on any type of vertical surface and attached directly to buildings or free-standing walls.50 Plants can have their roots in the ground, the wall itself or in an inert medium. These systems are suitable for small spaces and create unique ecosystems that enable underexploited vertical space to be used to grow plants and provide a habitat for insects and smaller animals.51

Balconies

Some dental practices may have balconies and this space can be used for pot plants including herbs, flowering plants or grasses. Where there is room, fruit and vegetables can be grown to provide locally-sourced food, further adding to the biodiversity and the overall network of green space.32,52

Roof eaves

Many bird species and bats are under threat, as their natural nesting sites are disappearing in urban areas.53 The eaves of a roof can be used to place artificial nest boxes for birds and bats and can be easily incorporated into new buildings or extensions. There are many types of ready-made nest boxes and the provision of different sized boxes for different bird species is recommended. Correct positioning of the boxes is vital to their success and factors such as the type of species to be supported, site height, direction of sunlight and prevailing wind, as well as proximity to fresh water for a bat box, should be considered.54

Ground covering

Dental practices should consider the type of ground covering they use within any outside area. Traditional road coverings such as concrete and tarmac do not provide any opportunity for plants and wildlife to live. Such ground covering also increases the risk of flooding, as the surface will not absorb any water. Dental practices could consider partially sealed surfaces, for example, gravel with grass coverage and/or non-sealed paving. Combining a useable surface with some vegetation provides greater potential for small plants and insects to exist.

Barriers and facilitators

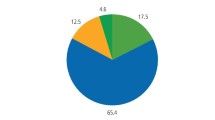

There are, however, a number of barriers and facilitators for the dental team to incorporate biodiversity changes in their open spaces. In a recent study by Harford et al., dental members who completed a questionnaire were very interested in becoming more environmentally sustainable, however there was a lack of awareness on how best to accomplish this.55 It is also clear from the latest NHS staff study that 98% of staff think it is important for the health and social system to work in a way that supports the environment. In ast udy in Ireland 69% of all dental team members responded that they were interested in environmental sustainability.55

A recent paper by Grose et al. highlighted some of the barriers to implementing sustainability changes within the dental practice.56 These included competing demands, personal motivation, the cost and time to implement such changes, and patients questioning the choice of the surgery to remove the lawn and replace it with something perhaps more wild and unkempt.57

From a biodiversity perspective, there are limited papers demonstrating the cost benefits of providing a biodiverse space. It is known that trees, by providing shelter and shade, can contribute to a reduction in a building's energy budget, through reduced air conditioning and improved solar gain.58 In an American study, it was demonstrated that once a native grassland was established, there was no mowing and no requirement for fertilisers, pesticides, herbicides or watering. This resulted in annual long-term cost reductions of around 80-90%, in comparison to the costs of traditional lawn mowing and maintenance.59

The practice also needs to consider the time constraints inherent in producing a biodiverse garden. These may be high in the short-term, but over the long-term it is more likely to be less time intensive than lawn mowing. The NHS Forest project works with volunteer organisations such as the British Trust for Conservation, who have developed the guidance pack for the organisation. It is possible that patient groups or local schools could help support the development and maintenance of the green space of a dental practice on a voluntary basis. Some patients may not have a garden of their own and may be grateful for the opportunity. Evidence from this comes from the experience of the Lambeth GP food co-op and the increasing waiting lists for allotments.60,61 Participants could share in any food produce produced by the garden.

The development of a green biodiverse space, like all sustainability initiatives would need to be led by a team member passionate about championing this change. As discussed in the seventh paper in this series, any sustainability initiative needs to have senior leadership with team members feeling incentivised and supported to make change. An example of existing practice, although not within dentistry, is the Lambeth food cooperative, an inclusive open project which is the result of a collaboration between 45 practices in Lambeth. Patients are supported by an experienced gardener to learn how to grow fruit and vegetables, and in the process interact with other people. Patients are encouraged to join, attending sessions run by practice nurses. The vision of Lambeth is to develop a vision of new environments for health and wellbeing, galvanising local communities, building the potential for greater resilience, and reducing social isolation and health inequalities.60

It may be possible for dental practices to seek charitable funding or work in partnership with health insurance companies. One example of this is the partnership between Bupa and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), which is transforming green spaces and encouraging wildlife into healthcare and residential environments.62 Alternatively, the practice could consider professional help to develop an eco-friendly space, using existing funds they currently spend on lawn installation and maintenance. There are a number of companies that specialise in ecological gardens.

The transition to an environmentally friendly dental practice environment need not be an all or nothing dichotomy. By incorporating measures that are logistically feasible into the day-to-day running of the practice, we can all take steps toward improving both ecological and human wellbeing.

References

Bridgewater P, Régnier M, Wang Z. Healthy Planet, Healthy People: A Guide to Human Health and Biodiversity. 2012. Available at https://www.cbd.int/health/doc/guidebiodiversityhealth-en.pdf (accessed April 2019).

Duane B, Hyland J, Rowan J S, Archibald B. Taking a bite out of Scotland's dental carbon emissions in the transition to a low carbon future. Public Health 2012; 126: 770-777.

Duane B, Berners Lee M, White S, Stancliffe R, Steinbach I. An estimated carbon footprint of NHS primary dental care within England. How can dentistry be more environmentally sustainable? Br Dent J 2017; 223: 589-593.

Duane B, Taylor T, Stahl-Timmins W, Hyland J, Mackie P, Pollard A. Carbon mitigation, patient choice and cost reduction - triple bottom line optimisation for health care planning. Public Health 2014; 128: 920-924.

Duane B, Harford S, Steinbach I et al. Environmentally sustainable dentistry: energy use within the dental practice. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 367-373.

Duane B, Ramasubbu D, Harford S et al. Environmental sustainability and procurement: purchasing products for the dental setting. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 453-458.

Duane B, Steinbach I, Ramasubbu D et al. Sustainability and travel within the dental practice. Br Dent J 2019; In press.

Duane B, Ramasubbu D, Harford S et al. Sustainability and waste within the dental practice. Br Dent J 2019; In press.

Hassan R, Scholes R, Ash N (eds). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Current State and Trends, Volume 1. London: Island Press, 2005.

Ceballos G, Ehrlich P R, Dirzo R. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signalled by vertebrate population losses and declines. PNAS 2017; 114: E6089-E6096.

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. State of Nature 2016. Available at https://www.rspb.org.uk/globalassets/downloads/documents/conservation-projects/state-of-nature/state-of-nature-uk-report-2016.pdf (accessed April 2019).

Hallman C A, Sorg M, Jongejans E et al. More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0185809.

Biesmeijer J C, Roberts S P, Reemer M et al. Parallel declines in pollinators and insectpollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science 2006; 313: 351-354.

Hallmann C A, Foppen R P, van Turnhout C A, de Kroon H, Jongejans E. Declines in insectivorous birds are associated with high neonicotinoid concentrations. Nature 2014; 511: 341-343.

Carrington D. Hedgehog numbers plummet by half in UK countryside since 2000. The Guardian (London). 2018 February 7.

Garibaldi L A, Carvalheiro L G, Leonhardt S D et al. From research to action: enhancing crop yield through wild pollinators. Front Ecol Environ 2014; 12: 439-447.

Fiedler A K, Landis D A, Wratten S D. Maximizing ecosystem services from conservation biological control: The role of habitat management. Biol Control 2008; 45: 254-271.

Poveda K, Steffan-Dewenter I, Scheu S, Tscharntke T. Effects of decomposers and herbivores on plant performance and aboveground plant-insect interactions. Oikos 2005; 108: 503-510.

Centre for Sustainable Healthcare. NHS Forest. Available at https://nhsforest.org/ (accessed April 2019).

Markevych I, Schoierer J, Hartig T et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ Res 2017; 158: 301-317.

Statista. Annual number of dental practitioners in the United Kingdom (UK) from 2010 to 2018 (in 1: 000). Available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/318885/numbersofdentalpractitionersintheuk/ (accessed April 2019).

Angold P G, Sadler J P, Hill M O et al. Biodiversity in urban habitat patches. Sci Total Environ 2006; 360: 196-204.

Samuelson A E, Gill R J, Brown M J, Leadbeater E. Lower bumblebee colony reproductive success in agriculture compared with urban environments. Proc Biol Sci 2018; 285: 20180807.

Urban Environment Project. Making space for biodiversity in urban areas. Available at http://www.uep.ie/pdfs/guidelines_CH2.pdf (accessed April 2019).

Jones E L, Leather S R. Invertebrates in urban areas: a review. Eur J Entomol 2012; 109: 463-478.

Olive A, Minichiello A. Wild things in urban places: America's largest cities and multi-scales of governance for endangered species conservation. Appl Geogr 2013; 43: 56-66.

Girling C L, Kellett R. Skinny Streets and Green Neighbourhoods: Design for Environment and Community. London: Island Press, 2005.

Goddard M A, Dougill A J, Benton T G. Scaling up from gardens: biodiversity conservation in urban environments. Trends Ecol Evol 2010; 25: 90-98.

Bretzel F, Vannucchi F, Romano D, Malorgio F, Benvenuti S, Pezzarossa B. Wildflowers: From conserving biodiversity to urban greeningA review. Urban For Urban Green 2016; 20: 428-436.

Baldock K C, Goddard M A, Hicks D M et al. Where is the UK's pollinator biodiversity? The importance of urban areas for flower visiting insects. Proc Biol Sci 2015; 282: 20142849.

Ratcliffe D (ed.). A Nature Conservation Review: Volume 1: The Selection of Biological Sites of National Importance to Nature Conservation in Britain: v.1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Johnston J, Newton J. Building Green: a Guide to Plants on Roofs, Walls and Pavements. London: Greater London Authority, 2004.

Pataki D E, Carreiro M M, Cherrier J et al. Coupling biogeochemical cycles in urban environments: ecosystem services, green solutions and misconceptions. Front Ecol Environ 2011; 9: 27-36.

Hicks D M, Ouvrard P, Baldock K C et al. Food for Pollinators: Quantifying the Nectar and Pollen Resources of Urban Flower Meadows. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0158117.

Buglife. Scottish Invertebrate Habitat Management: School grounds, parks and urban greenspace. 2011. Available at https://www.buglife.org.uk/sites/default/files/School%20grounds_0.pdf (accessed April 2019).

Garbuzov M, Ratnieks F L. Listmania: The strengths and weaknesses of lists of garden plants to help pollinators. BioScience 2014; 64: 1019-1026.

Lowenstein D M, Matteson K C, Minor E S. Diversity of wild bees supports pollination services in an urbanized landscape. Oecologia 2015; 179: 811-821.

United Nations Human Rights. Pesticides are 'global human rights concern', say UN experts urging new treaty. 2017. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21306&LangID=E (accessed April 2019).

Lye G C, Osborne J L, Park K J, Goulson D. Using citizen science to monitor Bombus populations in the UK: nesting ecology and relative abundance in the urban environment. J Insect Conserv 2012; 16: 697-707.

Rautio A, Valtonen A, Auttila M, Kunnasranta M. Nesting patterns of European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) under northern conditions. Acta Theriol 2013; 59: 173-181.

Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust. Hedgehog Way: Top Garden Tips. Available at https://www.gloucestershirewildlifetrust.co.uk/hedgehogwaytopgardentips (accessed April 2019).

Oertli B. Editorial: Freshwater biodiversity conservation: The role of artificial ponds in the 21st century. Aquat Conserv: Mar Freshw Ecosyst 2018; 28: 264-269.

Fortel L, Henry M, Guilbaud L, Mouret H, Vaissière B E. Use of human-made nesting structures by wild bees in an urban environment. J Insect Conserv 2016; 20: 239-253.

MacIvor J S, Packer L. 'Bee hotels' as tools for native pollinator conservation: a premature verdict? PLoS One 2015; 10: e0122126.

Francis R A, Lorimer J. Urban reconciliation ecology: the potential of living roofs and walls. J Environ Manage 2011; 92: 1429-1437.

Blackdown greenroofs. Available at https://blackdown.co.uk/ (accessed April 2019).

Oberndorfer E, Lundholm J, Bass B et al. Green Roofs as Ecosystems: Ecological Structures, Functions and Services. BioScience 2007; 57: 823-833.

Niachou A, Papakonstantinou K, Santamouris M, Tsangrassoulis A, Mihalakakou G. Analysis of the green roof thermal properties andinvestigation of its energy performance. Energ Buildings 2001; 33: 719-729.

Getter K L, Rowe D B. The role of extensive green roofs in sustainable development. HortScience 2006; 41: 1276-1285.

Perini K, Ottelé M, Haas E M, Raiteri R. Vertical greening systems, a process tree for green facades and living walls. Urban Ecosyst 2013; 16: 265-277.

Chiquet C. The animal biodiversity of green walls in the urban environment. StokeonTrent: Staffordshire University, 2014. PhD Thesis.

van den Berg M, Wendel-Vos W, van Poppel M, Kemper H, van Mechelen W, Maas J. Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban For Urban Green 2015; 14: 806-816.

Islington.gov.uk. Biodiversity in the Built Environment: Good Practice Guide 4. 2012. Available at https://www.islington.gov.uk//~/media/sharepoint-lists/public- records/planningandbuildingcontrol/publicity/publicconsultation/20122013/20121220 goodpracticeguide4biodiversity (accessed April 2019).

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Roofs for wildlife. Available at https://www.rspb.org.uk/makeahomeforwildlife/advice/helpingbirdstest/nestboxes/naturalnests/ (accessed April 2019).

Diffley M, Mohamed M, Birt R et al. How important is sustainability to the dental profession in Ireland? J Ir Dent Assoc 2019; 65: 39-43.

Grose J, Burns L, Mukonoweshuro R et al. Developing sustainability in a dental practice through an action research approach. Br Dent J 2018; 225: 409-413.

Richardson M. Our Lawns Are Killing Us. It's Time to Kick the Habit. 2017. Available at https://www.ecolandscaping.org/07/lawn-care/lawnskillingustimekick-habit/ (accessed April 2019).

HM Government. The UK Low Carbon Transition Plan: National Strategy for Climate and Energy. 2009. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228752/9780108508394.pdf (accessed April 2019).

American Society of Landscape Artists. Native Meadows and Grasslands: From Vision to Reality. 2015. Available at https://www.asla.org/uploadedFiles/CMS/Meetings_and_Events/2015_Annual_Meeting_Handouts/SUN-B06_Native%20Meadows%20and%20Grasslands.pdf (accessed April 2019).

Lambeth GP Food Co-op. What we do. 2018. Available at http://lambeth.gpfoodcoop.org.uk/Whatwedo (accessed April 2019).

Lewis W. Demand for allotments is growing. 2018. Available at https://www.propertyreporter.co.uk/household/demandforallotmentsisgrowing.html (accessed April 2019).

Smedly T. How green spaces can transform elderly care. The Guardian (London) 2012 November 12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duane, B., Ramasubbu, D., Harford, S. et al. Environmental sustainability and biodiversity within the dental practice. Br Dent J 226, 701–705 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0208-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0208-8

This article is cited by

-

Biodiversity preservation through sustainable dentistry: contextualising SDG 15

British Dental Journal (2024)

-

Environmental sustainability in endodontics. A life cycle assessment (LCA) of a root canal treatment procedure

BMC Oral Health (2020)

-

Environmental sustainability and travel within the dental practice

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Environmental sustainability: measuring and embedding sustainable practice into the dental practice

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Environmentally sustainable dentistry: energy use within the dental practice

British Dental Journal (2019)