Abstract

Aim To determine the prevalence and the epidemiology of the factors influencing endodontic complexities in general dental practice.

Method Eligible cases where endodontic treatment was indicated as a treatment option were collected by a total of 30 general dental practitioners based in the UK. Online-based Endodontic Complexity Assessment Tool (E-CAT) was used to determine the perceived complexity of each case. In total, 22 categories, including patient- and tooth-related factors, were recorded.

Results Collectively, 435 non-surgical root canal treatment cases were assessed. Overall, 72% of the root canal treatments encountered in general dental practice were found to be either uncomplicated (Class I) or moderately complicated (Class II) and can be considered within the remit of general dental practitioners. Despite the relatively equal distribution of the assessed teeth, the proportion of extraction as a proposed treatment for posterior teeth was more than double that of anterior teeth.

Conclusion The results obtained in this study provide a good resource and databank for researchers, educators, public health commissioners and academic institutions to access a wide range of information concerning the prevalence and distribution of endodontic complexity.

Key points

-

This is the first study of its kind to measure the epidemiology of root canal treatment complexity encountered by general dental practitioners in daily practice.

-

The distribution of endodontic complexity over Classes I, II and III (low, moderate and high) was 40%, 32% and 28%, respectively.

-

Teeth with existing extra-coronal restorations formed 18% of the cases encountered, while the history of trauma was recorded in 9% of cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The need for endodontic treatment in general dental care is well established, with several studies reporting a substantial need for non-surgical root canal treatment (NSRCT).1,2 A systematic review by Pak et al.3 revealed the prevalence of root canal-treated teeth to be around 10% of all teeth.

Endodontic treatments can vary significantly in their complexity. There appears to be a lack of good-quality epidemiological studies reporting the prevalence of complex root canal treatment or the factors behind such complexity. There is an extensive range of factors that are reported to affect the complexity of NSRCT.4,5,6,7 There are several cross-sectional studies describing the prevalence of periapical radiolucency in the population3,8 and other studies looking into the prevalence of root canal treatment within the population. Yet, possibly due to 'complexity' being a subjective matter, the literature review revealed no studies reporting the prevalence of complex endodontic cases in general dental practice.

There is currently no data on how endodontic complexities could affect the proposed treatment's decision-making to the case being assessed. Such information may help identify shortfalls within the health system and help guide future research to resolve such areas.

Aims

This study was designed to assess the epidemiology of non-surgical root canal treatment complexity in general dental practice. The aims were as follows:

-

1.

Determine the prevalence and distribution of the factors influencing endodontic complexities in general dental practice

-

2.

Assess the distribution of proposed dental treatment in relation to the complexity levels and factors.

Methods

Ethics approval for the study was sought and granted through the Integrated Research Application System (REC reference: 15/NE/0372).

The participating dentists were recruited through an announcement published on online dental forums and societies. The inclusion criteria were defined as general dental practitioners (GDPs) working solely in general dental practice in the UK. Cases treated by specialist endodontists or dentists with a special interest in endodontics were excluded from the study.

The participating GDPs' General Dental Council number, qualification year and practice address and nature (NHS or private) were recorded on a secure, password-protected database. Each GDP was provided with a personal identification number code to match their details when the data was recorded. Consent to take part in the study and use the data collected for research purposes was obtained from all participants.

The eligibility criteria were as follows: any patient presenting to their GDP with a pulpal/periapical disease in a restorable tooth where non-surgical root canal treatment was a viable treatment option. This included both emergency and routine appointments.

With a 95% confidence interval (CI = 95%), the sample size required was calculated to be 385 cases.

This study was incorporated within the Endodontic Complexity Assessment Tool (E-CAT).9 E-CAT is an interactive, online, digital tool that utilises an evidence-based approach to enable clinicians to assess the endodontic complexity of any non-surgical root canal therapy case. The criteria assessed include 22 categories analysing both patient and tooth-related factors. The tool is free to use and can be found online at www.e-cat.uk.

Each participating dentist was requested to record 10-15 consecutive cases using the E-CAT tool. All data was stored on an encrypted database with all responses anonymised; no patient data was required. The dentists had up to four months to complete their data collection.

Schneider, Weine, Lutein and Cunningham's methods of evaluating root curvature as summarised in Balani et al.10 were all considered for the study. As the Schneider technique was found to be the most commonly familiar and easiest to follow,11 it was selected for this research, despite the limitations associated with it.

Before starting the study, every participant was calibrated through a series of anonymised endodontic cases provided to them until 100% calibration was achieved. All eligible cases were included, regardless of whether patients chose to receive treatment or not. The participants were also asked to report on the outcome of the cases assessed.

Results

A total of three adverts were sent out. Overall, 44 dentists responded to the adverts, of which 30 were successfully enrolled onto the study. A total of three dentists were excluded due to working in a hospital environment, a further two were only accepting endodontic referrals, five did not complete the calibration exercise and the remaining four did not contribute with cases following their enrolment. The demographic distribution of the participants can be found in Table 1.

On average, the GDPs required 6.25 weeks (pro-rata; adjusted for annual leave or part-time work) to complete collecting ten cases; the range was as low as four weeks and up to eleven weeks. As a crude assumption, this study estimates that a full-time GDP working in the UK comes across an average of 1.6 (range = 0.9-2.5) potential root canal treatment cases a week, or 70.4 (39.6-100) annually.

Prevalence and distribution of complexity factors

Collectively, 437 non-surgical root canal treatment cases were assessed and recorded. Two dentists reported two separate erroneous entries. These were deleted, leaving a total of 435 cases.

Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5 show the distribution of the data recorded in endodontic cases in general dental practice.

The distribution of proposed treatment in relation to the complexity levels

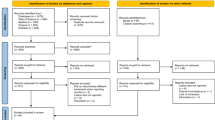

To further analyse the results and enable more meaningful interpretation, the study also investigated proposed treatment destination of each case encountered. The results are shown in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows the distribution of proposed treating clinicians in relation to the type of tooth (anterior or posterior) assessed for treatment. This includes cases with failed endodontic treatment (previously obturated cases).

Discussion

This cross-sectional epidemiological study was designed to explore the prevalence of the factors influencing the complexity of non-surgical root canal treatments in general dental practice.

An ideal epidemiological study would include a very large sample with as much detail of each category recorded as possible. Ideally, the data collection would be standardised through a series of examiners cross-checking the records to ensure minimal bias in recording the data. This is relatively easily achieved in the case of single item prevalence study (for example, periapical pathology). In contrast, the current study required a comprehensive root canal treatment complexity assessment consisting of numerous interdependent factors. Therefore, determining the prevalence of the root canal treatment complexity was found to be challenging and demanded that all relevant categories be recorded or accounted for in as much detail as possible. A thorough literature search to identify the factors affecting endodontic complexity was carried out to ensure most of the key categories are included in the surveying questions.9

To ensure an appropriate methodology is followed, only qualified dentists who passed the calibration process (including the Schneider technique tutorial for assessment of root curvature) were selected. However, it must be acknowledged that there are areas where clinicians' subjective opinion and recorded results still may vary (for example, radiographic canal visibility). To dilute the effect of the subjective variations, the number of dentists participating and the cases collected was aimed to be as high as possible. This is in line with the prevalence studies conducted in this field;3,12 a sample size of around 300-400 endodontic cases would be required. The nature of the study did not allow for cross-examination of the data to double-check the accuracy of the records, leading to a higher possibility of human error or bias during the data collection phase. Considering that this study exceeded the required sample size number for statistical significance (95% CI), this issue is less probable, but the data should still be analysed bearing this limitation in mind. On the other hand, the majority of the factors reported (for example, medical history or presence of previous endodontic treatment) were less subjective. The reliability of these results can be expected to be very good.

Although the results can provide us with an insight of the prevalence of reduced radiographic canal space and curved roots, the true prevalence of those values can vary due to the use of two-dimensional radiographs in the assessment of the endodontic cases. The observer variation in the assessment of root curvature, the angle of the radiograph and the method used to measure the curvature may also result in deviation from the true prevalence of anatomically curved canals to the results recorded here. It might be more accurate to state that the results concerning the prevalence of canal visibility and root curvature recorded in this study reflect their perceived prevalence by GDPs rather than the true value.

Overall, the majority (72%) of the root canal treatments encountered in general dental practice were found to be either uncomplicated (Class I) or moderately complicated (Class II) and can be considered within the remit of GDPs. This is based on the assumption that Class II complexity cases carry a moderate risk of complication but may still be within the remit of an experienced general dentist or dentists with further non-specialist training in endodontics. However, a relatively high proportion (28%) of the cases was found to be of higher complexity and carry a higher risk of complications and therefore ideally require specialist input. The boundary between what specialists and dentists with enhanced skills are expected to treat is a topic that was beyond the remit of this study.

Despite a relatively equal distribution of cases encountered with potential root canal treatment across anterior and posterior teeth, the proportion of extraction as a proposed treatment for posterior teeth is more than double that of anterior teeth. A relatively high percentage of previously root canal-treated teeth are either referred to secondary care or extracted in general practice. The proportion of teeth with Class III complexity and those with previous endodontic intervention being extracted was significantly higher than those previously unfilled. These can be due to patients' wishes, financial limitations, shortage of referral service, wish to accept a shortened dental arch13 or other factors.

Additionally, the results obtained in this research highlighted some public health queries. According to the latest registration report published by the General Dental Council in October 2021,14 the total number of registered specialists in endodontics was 322, which forms 0.75% of the dental workforce. Aside from the service provided by teaching hospitals, there is a large shortage of specialist endodontists to refer to within the NHS. This may explain the relatively high proportion (6%) of proposed referrals to dentists with special interest (DWSI) rather than to NHS secondary care or private specialists (5%) in endodontics. Many DWSI are now found in the UK and may indeed be helping to reduce the pressure on GDPs. With around 28% of the cases encountered requiring specialist input, it becomes immediately apparent that further research is required to utilise the results obtained here to assess the level of shortage of endodontic specialists within the UK health system. Further research is also needed to identify a more tangible system to recognise those dentists with a special interest in the field and the level of endodontic complexity that could be referred to them.

Conclusion

The results obtained in this study provide a good resource and databank for researchers, public health commissioners and academic institutions to access a wide range of information concerning the prevalence and distribution of endodontic complexity.

References

Saunders W P, Saunders E M, Sadiq J, Cruickshank E. Technical standard of root canal treatment in an adult Scottish sub-population. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 382-386.

De Moor R J, Hommez G M, de Boever J G, Delme K I, Martens G E. Periapical health related to the quality of root canal treatment in a Belgian population. Int Endod J 2000; 33: 113-120.

Pak J G, Fayazi S, White S N. Prevalence of periapical radiolucency and root canal treatment: a systematic review of cross-sectional studies. J Endod 2012; 38: 1170-1176.

Sjogren U, Hagglund B, Sundqvist G, Wing K. Factors affecting the long-term results of endodontic treatment. J Endod 1990; 16: 498-504.

Messer H H. Clinical judgement and decision making in endodontics. Aust Endod J 1999; 25: 124-132.

Ree M H, Timmerman M F, Wesselink P R. Factors influencing referral for specialist endodontic treatment among a group of Dutch general practitioners. Int Endod J 2003; 36: 129-134.

Kabir J, Mellor A C. Factors affecting fee setting for private treatment in general dental practice. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 200-203.

Hamedy R, Shakiba B, Pak J G, Barbizam J V, Ogawa R S, White S N. Prevalence of root canal treatment and periapical radiolucency in elders: a systematic review. Gerodontology 2016; 33: 116-127.

Essam O, Boyle E L, Whitworth J M, Jarad F D. The Endodontic Complexity Assessment Tool (E-CAT): A digital form for assessing root canal treatment case difficulty. Int Endod J 2021; 54: 1189-1199.

Balani P, Niazi F, Rashid H. A brief review of the methods used to determine the curvature of root canals. J Restor Dent 2015; 3: 57-63.

Günday M, Sazak H, Garip Y. A comparative study of three different root canal curvature measurement techniques and measuring the canal access angle in curved canals. J Endod 2005; 31: 796-798.

Hebling E, Coutinho L A, Ferraz C C R, Cunha F L, Queluz D de P. Periapical status and prevalence of endodontic treatment in institutionalised elderly. Braz Dent J 2014; 25: 123-128.

KäyserA F. Shortened dental arches and oral function. J Oral Rehabil 1981; 8: 457-462.

General Dental Council. Registration report October 2021. 2021. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/docs/default-source/registration-reports/10.-registration-report---october-2021.pdf?sfvrsn=5b907c7d_3 (accessed November 2021).

Acknowledgements

This journal article was based on a doctoral thesis submitted by the first author to the University of Liverpool, completed in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the DDSc degree.

Funding

The development of the Endodontic Complexity Assessment Tool (E-CAT) was awarded a grant from the European Society of Endodontology to assist in the development and programming of the tool and host it on a secure permanent server. The Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust sponsored the research throughout its conduct period.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Obyda Essam: conception and development of idea, data analysis, interpretation of results and editing of manuscript. Dariusz Kasperek: data analysis, interpretation of results and editing of manuscript. Edward L. Boyle and Fadi Jarad: conception and development of idea, editing of manuscript and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2022

About this article

Cite this article

Essam, O., Kasperek, D., Boyle, E. et al. The epidemiology of endodontic complexity in general dental practice: a prevalence study. Br Dent J (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4405-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4405-5