Abstract

Introduction Oral disease in very young children is far more common among children in deprived and vulnerable families than among their peer group. Such children are at the highest risk of requiring a general anaesthetic for removal of decayed primary teeth.

Aim This study aimed to create new knowledge about how best to promote oral health among a target population, about who very little is established with regard to how to successfully intervene to improve long-term oral health.

Method Phase one of the study developed a logic model, and phase two delivered an oral health-promoting intervention by working with the Family Nurse Partnership. The social and empirical acceptability of the intervention was explored, and the attributes needed by people delivering such an intervention were investigated in-depth.

Results The thematic analysis of phase one data produced seven key themes which appeared to influence parents' ability and willingness to accept an oral health intervention aimed at their infants. These were: their personal experiences, current oral health knowledge, desire for dental care for their child, the timing of an intervention, their perception of difficulties, family norms and the level of trust developed.

Conclusion It is possible to motivate the most vulnerable families to establish behaviours which are conducive to good oral health, and that intervention is feasible and appropriate if a trusting relationship is adopted by the deliverer of the intervention. Families were successful in adopting oral health behaviours and visiting dental services when such circumstances were established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

With a real understanding of the context of a family's life, oral health promotion in very early life can be highly effective.

-

Suggests building confidence in young parents and supporting their autonomy, rather than 'telling them what to do' is much more likely to be effective in producing positive health behaviours.

-

Argues the availability of supportive, non-judgmental professional dental services is highly valued, even by the most vulnerable families.

-

Suggests if such dental services are run by the appropriate personnel, they are utilised and appreciated.

Introduction

Oral health promotion should occur in the early years of a child's life and tailored interventions should be delivered to groups at high risk of poor oral health.1 Dental disease is the commonest reason for children being admitted to hospital,2 and there is an eightfold difference between the levels of decay in five-year-olds in the most and least deprived areas.3 In addition, socially-deprived children who are at the highest risk of dental disease are the most common users of general anaesthetic (GA) services for tooth extraction.2 Loss of teeth early in life affects quality of life, life chances, and long-term oral health.4,5,6,7,8 Therefore, focusing on eradicating, or at least reducing childhood caries, offers a mean of reducing the gross inequalities in oral health which exist.

Effective health promotion and disease prevention in early life can produce measurable benefits in health, and these benefits extend to future educational achievement, economic productivity and responsible citizenship. An initiative which is designed to ensure the future wellbeing of vulnerable infants is the Family Nurse Partnership (FNP) which offers support to infants considered to be at high risk of many chronic diseases and social problems.9 FNP provides intensive support for vulnerable first-time young mothers and their families, including those from highly disadvantaged areas and backgrounds (for example, looked after children who are young parents). Young parents are paired with a specially-trained family nurse (FN) who visits them regularly, from the early stages of pregnancy until their child is two years old.

Through a psycho-educational approach and a focus on positive behaviour change, FNP enables young parents to:

- 1.

Build positive relationships with their baby and understand their baby's needs

- 2.

Make positive lifestyle choices that will give their child the best possible start in life

- 3.

Build their self-efficacy

- 4.

Build positive relationships with others, modelled by building a positive relationship with the family nurse.

This organisation's model underpinned the study described below and, by attaching an oral health worker to a family's FNP nurse, access to these 'hard to reach' families was achieved. The aim was to create new knowledge about how best to motivate a target population known to be at very high risk of oral disease and about whom very little is established with regard to how to successfully intervene to change the behaviours which are conducive to long-term oral health.

This two-phase qualitative study was informed by: i) Bandura's self-efficacy theory;10 ii) motivational interviewing;11 and iii) a 'strengths-based' approach.12 It used an action-research, client-driven methodology13 to delineate the facilitators and barriers to success and devise an appropriate intervention, which would promote the behaviours which are known to support good oral health.14 Ethical approval was given by the South-West Central Bristol Research Ethics Committee (REC Ref. 16/SW/0165) and all participants were assured that there was no detriment to them if they did not join or complete the study.15

Methods

Phase one was an exploratory phase, which developed and refined a logic model (Fig. 1) for promoting positive oral health behaviours in families with social difficulties. In phase two, the proposed intervention was delivered and an embedded process evaluation examined its ethical, social and empirical acceptability, and identified the competencies and capabilities needed to maximise the effectiveness of the intervention.

After these initial exploratory phases, if the results indicated that the intervention had had a positive effect on the children and families, a third phase of research, examining the effectiveness and efficacy of the intervention, would be implemented.

Phase one

An initial logic model was developed to inform the data collection in phase one, in which eligible clients were identified by their family nurse and ten parents were purposively sampled. The participants were aged between 18-21, with babies aged between 21 days and 23 months. Participants undertook the semi-structured interviews in their own homes with a researcher (JE). The interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data were analysed using thematic analysis, which allowed commonalities and divergences across interviews to be explored, silences identified, and themes which had not formed part of the initial thinking to emerge. Data collection and analysis were carried out contiguously to allow for insights from the ongoing analysis to identify themes to explore in future interviews. Codes were built into cross-cutting themes in order to summarise the data and these were used to develop an understanding of how the intervention would work and how it would best be delivered.

Intervention delivery

In phase two, an intervention was delivered to 15 FNP mothers by a researcher acting as, and exploring the role of, an oral health worker. Parents who had infants of an appropriate age were visited up to three times (additional support was available if desired and required). The first visit was intended to take place before the eruption of the first tooth, so contact was made when the infants were four months old. The oral health worker/researcher was introduced by the family nurse and prioritised building a supportive relationship with the family. A motivational interviewing, non-directive, style was adopted to build participants' sense of competence, control and connectedness. Visits occurred when the participant families requested one, at a time and place which they chose, although the research oral health worker (AG) kept in regular contact with the family throughout.

Phase two: data collection and analysis

An embedded formative process evaluation of the intervention delivery consisted of reflective field notes made after each visit with participants and semi-structured interviews with ten of the intervention participants (JE). These explored their experience of a visit, what was thought useful, and if anything different was needed. Interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Framework analysis explored how the components of the intervention worked. The final framework and summaries were reviewed and their meaning discussed by the study team.15

Results

Phase one

The analysis produced seven key themes which influenced parents' ability and willingness to accept and interact with an oral health intervention aimed at their infants. There were some overlaps between themes which reflected how these issues interacted within the participants' lives.

Personal experiences

The young parents spoke about their own experiences of oral health when talking about whether good oral health was important for their infants and their ability to achieve that. These experiences included peoples' reaction to those with poor oral health, previous visits to dentists, and their own parents' approaches to oral health.

It was important to participants that their teeth were healthy, looked good and did not cause any pain. Participants believed that people ridicule and make negative judgements about those with 'bad' teeth. Participants spoke about their own and friends' experiences of the way bad teeth affected self-confidence, happiness and social life. They were motivated to protect their infants from this:

'To me they're really important because I used to have really wonky teeth that used to really knock down my self-confidence cos [sic] I never used to smile because I used to feel that some people would pick on you and some people did. And it's just… I think a smile can make you more confident so I think teeth are actually really important in how someone feels about themselves and their confidence and everything' (P1:2);

'Yeah yeah my mum, my partner's friend's girlfriend she ended up losing all her teeth quite young and she, this year she's had them all replaced and had false teeth put in. She's very happy with it now and she's very confident with herself now because before she had all the gaps and stuff and it was all in the front as well so, so it's not like it was hidden. And she was quite self-conscious about it and obviously it would get her down a lot but she's had it all sorted now and she's, she's out quite a lot more and she's a lot happier now' (P1:1).

Participants' descriptions of their own teeth ranged from 'good' to 'awful' and their experiences with dentists were mixed. For some the experience had been fine and even 'fun'. For others it had been very negative and had had a lasting effect on their attitudes towards dental care. It was acknowledged that early negative experiences could set up a negative cycle:

'Yeah I think it's a giant circle isn't it… once you um, start not to like it [the dentist], once you've had one thing done you start to not to like it and then because you don't like it you start to miss it and then you get having to have more done and it's just like a big terrible circle' (P1:5);

'So when I was going to the dentist it was always bad, it was always fillings or numb [sic] and you know, just set up for a bad vibe' (P1:4).

Participants acknowledged the important role which their own parents played in establishing good dental care when they were children. They recognised the long-term effects of their parents' behaviours on their own attitudes towards tooth care and dental professionals. Participants spoke about the importance of seeing their own parents being role models for toothbrushing, and participants who had had problems with their teeth blamed their parents for not insisting on them brushing their teeth and for not being persistent in their efforts to get their children to care for their teeth.

'No umm, yeah obviously they brought toothbrushes and whatnot, we always had it there but it was never, like with [the baby] at the moment it needs to be a game for him to enjoy it and it was never introduced at a young age for us to enjoy it when we got older and it never become a routine whereas I really want it to be a routine for [the baby] so he gets used to it' (P1:4).

Oral health knowledge

The level of knowledge about how to maintain oral health in their baby varied widely and was not high in the participants' priorities. There was some awareness about the importance of avoiding sugared drinks in bottles and not putting their baby to bed with a bottle. Similarly, there was a general awareness of the need for their baby to progress from bottle to cup, but there was a lack of clarity over when, why and which type of cup to use. Mothers knew that they should brush their baby's teeth but they were very unclear at what age to start, knew very little about the benefits of fluoride toothpaste and were worried that the toothpaste would be 'too strong' for their baby's sensitive mouth. There were interesting attitudes and opinions about which foods were good or bad for their baby's teeth:

'Yeah no [sic] I'd rather her have little sweets like that than something like chocolate because I think chocolate… chocolate makes her constipated for some reason and I think chocolate there's more like sugar and crap in that than like something that's got a like little coated bit of sugar on like fruit pastilles or something like that' (partner of P1:9).

Visiting dental services

All the participants expressed the desire for their children to have a positive experience when seeing a dentist and the choice of dentist was important to them. Most of the participants emphasised the importance of having a kind, child-friendly dentist and of their baby going to see the dentist while they were still very young. They suggested ways in which the dentist could make the experience positive for their child; for example, allowing the baby to accompany the mother to a dentist visit so that it could share the experience of a check-up:

'No umm, I need to go for a check-up soon so I'm going to take him with me and just like even if he just sits in the chair or something just to like ease him into it even if they don't like look at it just to get him familiar with where it is and what it is… so yeah but I'm awful with the dentist I need to man up and do it anyway' (P1:6).

Timing

There was a range of views on when an oral health promotion intervention should begin. Some felt weaning was the most appropriate time and some thought 2-3 months of age was the time when support would be most acceptable and most appreciated. But the strongest feelings were in the participants who felt the best time for the intervention to start was around the time when their baby started teething. Teething was considered to be an exciting developmental milestone when parents started to think about dental health:

'Yeah, umm, it was a bit of a, it was a milestone wasn't it, I took a couple of pictures of his teeth but he, umm, he's always dealt well with his teething so I was just happy that he had them' (P1:5).

Teething was also described as being the cause of some anxiety and of people drawing comparisons with other children. It was also thought to be a time when they would have questions which they would like to be answered (was the tooth coming through normally? Are the teeth developing correctly? What is the normal growing pattern? Why is my baby taking longer than other babies?).

What was wanted?

Participants actively wanted support and advice with brushing and how to establish it as routine early on with their children. They were also interested in receiving advice on their child's dental development and most participants also said they would welcome support in finding a 'good' child-friendly NHS dentist with whom they felt confident and comfortable.

Changing established behaviours was perceived as more difficult than starting new ones and some changes were considered to be particularly challenging for parents. For example, stopping putting the baby to bed with a bottle was considered to be extremely difficult. This was an established behaviour which mothers believed was necessary for the baby to sleep and they believed that stopping this would mean that the baby would not settle, leading to lost sleep for the parent(s) and other members of the household:

'Yeah she always has her bottle when she goes to bed cos [sic] she can't get off without it. [The FNP nurse] has said about not giving her a bottle in bed but if she don't [sic], if she don't have it then she makes a right fuss. [The FNP nurse] said just water down her milk bit by bit but I...' (P1:3).

Family norms

The difficulty of changing established behaviours also related to whether these new behaviours challenged the norms of family and peers. Toothbrushing was a behaviour that was accepted as a social norm. Having a clean healthy mouth was universally seen as a desirable thing and establishing good dental hygiene was unequivocally accepted as the 'right thing to do'. In contrast, attitudes towards sugar were much more ambiguous and variable. There was an awareness among participants that too much sugar is bad for teeth and that sweet drinks and sugary foods should be avoided. A number of participants also explicitly attributed their own poor dental health to their consumption of sweets and sugary foods. However, some parents felt it was that it was acceptable and even necessary to give babies sweet things. Some parents gave their babies juice, due to their belief that sugar was a necessity in the baby's diet:

'He's still having sugar, he's still having juice, you can't avoid sugar completely cos else [sic] they won't eat would they?' (P1:6).

Attitudes towards sugar were complex and sugary foods were linked with celebration, treats and nurturing. Indeed, one participant spoke explicitly of how her mother tried to 'buy' her baby's love with sugar:

'Maybe they think he'll love them more if they give him sugary sweets. But no, it's not the case it just makes him poorly' (P1:1).

The importance of a trusted relationship

Universally, the participants spoke positively about their relationships with their family nurse. They found the relationship with her profoundly helpful and held it in very high regard. Typifying this are the following quotes:

'It was mainly [FNP nurses] I turned to and then things were… Like my experiences I just I didn't want them to be similar to what [the baby] gets, do you know what I mean… She stands by me and she will guide me through until I feel confident to be able take that next step umm cos [sic] I'm always thinking that I don't do good enough for [the baby]. When you're a young parent and you're sort of on your own and been through a harsh time like I have, having someone that helps you to make sure that the child walks, not the same path but further than what you could ever walk is like nice to know… It's been a lifesaver really' (P1:4);

'An' no she's so good with [the baby] and she she's just really umm what's the word, I'm not very good with words today [J laughs] she like she she [sic] just eggs you on like she always makes you feel like you're doing a good job. Even when you feel like you're not, even when you in the deepest darkest moment of motherhood she feels like you're doing an amazing job so yeah she is amazing and I love her' (P1:6).

Participants particularly valued the one-to-one personalised support that they received. They spoke particularly about the non-judgemental nature of the relationship and the fact that the family nurses were usually mothers themselves. The FNs helped participants with all aspects of their lives including accommodation, finance, work and relationships. The trust that the participants felt for the FNs was very apparent and clearly a powerful factor in their making informed choices.

The parents (who were all female) who participated in the phase one interviews were keen to care for their babies' teeth in the best ways they could. They were very positive about the proposed oral health intervention, particularly about the possibility of having a dedicated one-to-one worker who would support them to care for their babies' teeth and, although their trust was primarily in their family nurse, they felt someone specifically dedicated to supporting oral health would be a good thing and they were happy for the support worker to visit them in their homes.

Participants spoke explicitly about the depth of the relationship with the FNP nurse being at the centre of their trust in the advice given. They suggested that the building of a trusted, open relationship between an oral health worker and the participants should be a key aim of the intervention.

Phase two

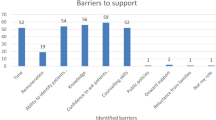

The framework analysis of phase two data produced two crosscutting themes:

- 1.

Barriers and facilitators relating to the five target behaviours

- 2.

Issues concerning the delivery of the intervention.

These deductively-derived themes were informed by inductively emergent codes and columns which included the support and influence of participants' own parents, their confidence in their ability to parent, the stability of living arrangements, the degree of power which they were able to enact in controlling their living environments, and their desire to put their infants' needs first. The intervention was welcomed by most of the participants and many commented about and were pleased and proud of the changes in their behaviours which it had stimulated:

'It's gone from having breakfast to now sitting down having breakfast, brush her teeth, carry on her day, bedtime milk, brush teeth and then bed so obviously the routine changed' (P2:5).

Even participants whose baby's teeth had not erupted within the project reported a perception that they would be able to establish a routine when the teeth did erupt.

The provision of toothbrushes, toothpaste and timers was greatly appreciated by participants. These items were also helpful because they gave the opportunity for discussions and demonstration. Interestingly and importantly, participants found that the information about looking after their babies' teeth influenced how they took care of their own mouths:

'Before when I was brushing my teeth every morning and every night I would just give them a quick flash over, I didn't really scrub them. Then [the oral health worker] gave me a timer. Now… I use it myself every morning and every evening, actually stand at the sink for two minutes… yeah I was literally, I must have been spending about 30 seconds brushing my teeth' (P2:10).

Toothbrushing with an appropriate fluoride toothpaste seemed to be the easiest of the target behaviours to achieve.

Participants perceived that diet control required parental strength, as it required the rejection of marketing and societal pressures to give babies and children sweet treats and drinks. For some, this induced a feeling of guilt when they denied their babies sweet treats. Furthermore, some felt that sweet treats were a way of showing kindness and love and making sure their babies did not 'miss out'. Certain sweets were seen as more suitable for babies and as potentially causing less harm. White chocolate was believed to be less unhealthy than milk or dark chocolate. Not putting infants to bed with a bottle was particularly challenging, particularly for those who did not have much control over the noise levels in their living environments. Participants generally did not know that free-flow cups were desirable when progressing from a bottle, and were grateful for advice about which types complied with health advice.

The opportunity to be referred to a child-friendly dentist was a highly valued element of the intervention, particularly to those participants who had specific needs. Feedback from attendees was very positive:

'I was expecting her to go away and say "oh they said no". But to be referred to the dentists and that was really good and she was just genuinely really friendly' (P2:13).

A number of participants moved home during the course of the study, some from living with their parents to living independently and vice versa. A move in location usually led to disruption of any of the above behaviours which had previously been established and often resulted in new barriers to implementing them.

These post-intervention interviews provided important insights into the challenges participants faced. Autonomy and their degree of control over the stability of their environment were issues that were particularly problematic. These were significant barriers to achieving behaviour changes, particularly those relating to foods and feeding. The parents were motivated to do their best for their infants, including their oral health, even though they did not always prioritise this. Lack of knowledge and conflicting information (particularly that coming from other family members) was problematic. The FNP nurse, and potentially an oral health worker, were recognised as trustworthy sources of knowledge.

A motivational interviewing style, person-centred approach, and establishing a supportive relationship before starting to give advice is clearly essential to any intervention with vulnerable participants. Giving advice, as and when the participant requested it, rather than giving advice that the oral health worker thought they needed to hear, enhanced the effectiveness of the intervention. Working in this way required thorough initial training and ongoing reflective support and development.

The initial introduction of the project by the family nurses, who the participants trusted, was vital. The best form of initial contact was found to be when the oral health worker visited with the family nurse. Participants also valued flexibility in ongoing contact. Some participants felt that they had all the information they needed at the first visit. Others, particularly those facing more challenging social situations, required several visits and ongoing telephone support. Proactive and ongoing contact was particularly valued. Participants said that being visited in their own homes was very important and made them much more likely to take part. Flexibility in the content of what was delivered, based on the parents' information needs was also highly valued, as was being able to concentrate on oral health rather than the wider issues that they discussed with their family nurses.

Conclusions

Given the 'Dental Check by One' initiative, the results of this study are important. It is possible to motivate the most vulnerable families to establish behaviours which are conducive to the family's oral health.16 However, it is important to recognise that intervention is feasible, acceptable and appropriate only if the following are taken into careful consideration:

- 1.

The approach taken is one of equality and acceptance of the families' norms by the oral health worker

- 2.

Development of trust between those people supporting vulnerable families and the families themselves is an essential component of efforts to promote positive behaviour change. The deep trust in which the participants in this study had in their family nurse was axiomatic to the acceptability and feasibility of this intervention

- 3.

Giving participants control and autonomy influenced the acceptability of, and receptivity to, the intervention. In particular, families controlling the timing of the visits, rather than the intervention being imposed on them, promoted the feasibility of the intervention

- 4.

The nature of the relationship between oral health worker and client is more important to the success of an intervention that the oral health worker's knowledge levels. Therefore, the selection of staff is as important to its success as the content

- 5.

Although it is day-to-day behaviours in the home which dictate oral health, rather than dental visiting, the provision of access to dental personnel who are experienced and well trained in working with vulnerable families is considered hugely beneficial and was greatly appreciated

- 6.

Dietary practices were much more dictated by family and peer norms than brushing. Because brushing is a social norm it is much easier to establish than diet control

- 7.

Times of heightened stress and disruption in the families, such as a change in living quarters, were times when support was particularly needed in order to maintain positive behaviours.

The limitations of this research are the relatively short time period over which data was collected, and the consequent fact that it was not possible to measure the intervention's effect on long-term health and wellbeing outcomes. However, having established that it is feasible to deliver an acceptable intervention and to collect research data from participants, future stages of this work will include delivery of the intervention at more than one site and evaluation of its efficacy in a trial of sufficient size and over a time period which would allow evaluation of the interventions effect on extraction rates and quality of life.

Very few previous studies have identified appropriate methodologies for improving oral health behaviours within vulnerable families from the start of a baby's life; the majority of interventions having focused on prevention of decay when the child has reached school years.16 As both habitual behaviours and the primary dentition are established long before this time, despite its limitations, the findings of this study are of significance.

References

National institute for Health and Care Excellence. Oral health: local authorities and partners. 2014. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph55/chapter/About-this-guideline (accessed July 2019).

NHS Digital. Tooth extractions for children admitted as inpatients to hospital, aged 10 years and under. 2019. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/clinical-indicators/nhs-outcomes-framework/current/domain-3-helping-people-to-recover-from-episodes-of-ill-health-or-following-injury-nof/3-7-ii-tooth-extractions-due-to-decay-for-children-admitted-as-inpatients-to-hospital-aged-10-years-and-under (accessed July 2019).

Public Health England. National Dental Epidemiology Programme for England: Oral health survey of five-year-old children 2012: A report on the prevalence and severity of dental decay. London: Public Health England, 2013. Available at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160603145410/http://www.nwph.net/dentalhealth/Oral%20Health%205yr%20old%20children%202012%20final%20report%20gateway%20approved.pdf (accessed July 2019).

Ronnerman A. The effect of early loss of primary molars on tooth eruption and space conditions. A longitudinal study. Acta Odontol Scand 1977; 35: 229-239.

Locker D. Concepts of oral health disease and the quality of life. In Slade G D (ed) Measuring oral health and quality of life. pp 11-25. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1997.

Malek Mohamaddi T, Wright C M, Kay E J. Childhood growth and dental caries. Community Dent Health 2009; 26: 38-42.

Alalunsua S, Kleemola-Kujala E, Nystrom M, Evalaht M, Groonroos L. Caries in the primary teeth and salivary streptococcus mutans and lacto bacillus levels as indicators of caries in permanent teeth. Paediatr Dent 1987; 9: 126-130.

Tickle M, Kay E J, Bearn D. Socio-economic status and orthodontic treatment need. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1999; 27: 413-418.

Wu J, Dean K S, Rosen Z, Muennig P A. The cost-effectiveness analysis of nurse family partnership in the United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2017; 28: 1578-1579.

Bandura A. The anatomy of stages of change. Am J Health Promot 1997; 12: 8-10.

Miller W R, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press, 2002.

Rath T, Clifton D O. How full is your bucket? Positive strategies for work and life. London: Gallup Press, 2004.

Hart E, Bond M. Action research for health and social care: a guide to practice. London: Open University Press, 1995.

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 3rd ed. London: Public Health England, 2017. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605266/Delivering_better_oral_health.pdf (accessed July 2019).

Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative analysis for applied policy research. London: Sage Publications, 2002.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Oral health: local authority oral health improvement strategies. Evidence review 1: review of evidence of the effectiveness of community based oral health improvement programmes and interventions. 2014.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Medical Research Council Public Health Intervention Development. Fund Grant No MR/N011449/1. The study was undertaken with the understanding and written consent of each participant and was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kay, E., Quinn, C., Gude, A. et al. A qualitative exploration of promoting oral health for infants in vulnerable families. Br Dent J 227, 137–142 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0528-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0528-8