Abstract

Head and neck cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the UK. Management may include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or a combination of these. A multidisciplinary approach is required, with the dental team forming an integral part of the patient pathway. Prior to commencement of cancer therapy, patients should have a dental assessment and urgent treatment should be provided as necessary. This article presents the case of a 49-year-old male with previous T4N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the pharynx. Surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy had been provided four years prior to presentation. The patient had significant post-operative complications of cancer therapy which were significantly affecting his quality of life. The patient underwent dental treatment, including preventive care, periodontal therapy and restorative care, with the multidisciplinary dental team. This case illustrates that oral assessment and urgent dental treatment should start prior to cancer treatment. Post-operative regular dental follow-ups should be instigated for monitoring and maintenance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Describes the role of the dental team in the multidisciplinary head and neck cancer pathway.

-

Details the dental management of a patient with head and neck cancer.

-

Outlines the common orofacial complications of head and neck cancer therapy.

Introduction

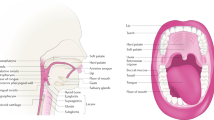

Head and neck cancer (HNC) can affect various structures including the upper aerodigestive tract (nasal cavity, oral cavity, pharynx and larynx), paranasal sinuses, and salivary and thyroid glands.1 It is the eighth most common cancer in the UK and accounts for 3% of all cancers.2 It is predicted that oral cancer incidence will continue to increase.3 Depending on the stage and site of the disease, patients may undergo surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.4,5 Management requires a multidisciplinary approach,4 with the dental team forming a vital component of the wider team.6 Dental professionals are increasingly likely to become involved in the management of this cohort.

There is no universally accepted pre-cancer therapy dental protocol due to lack of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of specific protocols. The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS Eng) and Restorative Dentistry-UK have produced guidelines for the oral management of oncology patients, including patients undergoing HNC therapy.7,8 It is recommended that patients undergo oral assessment before cancer therapy, and it is the responsibility of the medical team to instigate this. A preventive regime should be instigated and urgent dental treatment completed, including the removal of teeth with a poor prognosis. Although routine dental treatment should be avoided while the patient is undergoing cancer therapy, access to supportive oral care should be available to assist in the management of acute complications. As part of the oncology discharge protocol, plans should be in place for continued oral care. It is recommended that follow-up occurs at least biannually.

This is a case report of a patient who was diagnosed with HNC, where this dental pathway was not in place. The patient did not have a dental assessment pre-cancer therapy and presented several years after completing treatment. The case demonstrates the complications encountered if there is lack of a coordinated approach, the management of a HNC patient, and the importance of a clear dental pathway.

Case report

A 49-year-old male presented to the special care dentistry (SCD) department at a London-based teaching hospital. He was referred by the medical oncology team for dental management as reportedly the local dentist was having challenges providing treatment due to limited mouth opening.

Presenting oral complaint

The patient's main presenting complaint was that he was in constant pain and his teeth were 'breaking down', especially following radiotherapy. In addition, due to his limited mouth opening, he experienced difficulties receiving dental treatment of posterior teeth.

Medical history

The patient was diagnosed with T4N0M0, poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the parapharyngeal, oropharynx and nasopharynx, four years before presentation. He received two cycles of chemotherapy (cisplatin and fluorouracil), which were ceased due to the deterioration of his renal function. Therefore, radical radiotherapy was given at 65 Grays (Gy) in 30 fractions. Follow-up scans revealed treatment response with persistent local disease.

Later that year, the diagnosis was revised to a high-grade hyalinising clear cell carcinoma of the pharynx, for which he received four cycles of a different chemotherapy regime (carboplatin, fluorouracil and cetuximab), followed by maintenance chemotherapy (cetuximab). Although curative surgery was not possible, the patient underwent resection of the right parapharyngeal tumour to improve function.

A year and a half later, he was diagnosed with locally recurrent disease associated with lung and pleural metastasis. He received a further course of chemotherapy (carboplatin and paclitaxel), with six cycles in total. There was evidence of a small volume of recurrent mass in the right masseter space, which is under observation. The lung metastasis is also on surveillance. In addition, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was placed due to difficulties with chewing/swallowing.

The rest of his medical history was unremarkable. He took regular analgesia, namely ibuprofen and paracetamol, for pain control, largely due to discomfort from his teeth.

Dental history

Although the patient had not received a dental assessment before or during cancer therapy, he sought dental care when his teeth began to deteriorate and he was seen biannually. Dental treatment and attempts at stabilising the teeth were undertaken with local anaesthesia, with the additional adjunct of intravenous sedation for dental extractions. Toothbrushing was attempted three times per day with a fluoride toothpaste (1,450 ppm sodium fluoride). In addition, he used chlorhexidine 0.2% mouthwash four to five times per day, largely because he felt it was too uncomfortable to brush his teeth effectively. Although he was largely PEG-fed, he was able to have pureed food orally, in addition to drinks, with one litre of fruit juice consumed per day and coffee with sugar three times per day.

Social history

The patient lived alone and independently. He was an ex-smoker, having stopped one year after his cancer diagnosis. Prior to this he smoked approximately ten cigarettes per day for ten years. Average alcohol consumption was 1-2 units per week.

Clinical examination

Extraoral examination revealed tenderness of the right temporomandibular joint on palpation, and deviation to the left-hand side on opening. The right masseter and lateral neck muscles were fibrosed and firm. The maximum inter-incisal distance was 21 mm (Fig. 1).

Intraorally, saliva was thickened, viscous and frothy. The clinical oral dryness score was three out of ten, indicating mild xerostomia.9 Chronic oral mucosal atrophy was observed with sensitivity on contact; this was most prominent on the right buccal mucosa (Fig. 2) and palate. There was white coating on the dorsum of the tongue and keratosis of the right lateral border (Fig. 3). On the upper right edentulous alveolar ridge in the region of the 17, a pinpoint 2 mm probing depth through the mucosa was observed.

The gingiva was inflamed and tender to palpation and probing. Gross plaque and calculus deposits were evident, predominantly lingually and posteriorly. There was dental caries of 17 teeth (11, 12, 13, 14, 15; 21, 22, 23; 31, 32, 33, 37; and 41, 42, 43, 44, 45), four (14, 15, 37, 45) of which were unrestorable (Fig. 4).

Investigations

Radiographic investigations were undertaken, namely an orthopantomogram (Fig. 5) and full mouth periapicals. The extent of caries was confirmed, as well as presence of periapical radiolucency associated with the lower left second molar (37). In addition, a retained root of the upper right second molar (17) was confirmed. Bone loss around the remaining teeth was minimal.

Dental diagnoses

The following diagnoses were made:

- 1.

Objective mild-moderate xerostomia

- 2.

Chronic atrophy of the oral mucosa

- 3.

Chronic gingivitis

- 4.

Multiple carious lesions (11, 12, 13, 14, 15; 21, 22, 23; 31, 32, 33, 37; and 41, 42, 43, 44, 45)

- 5.

Chronic apical periodontitis of the 37

- 6.

Retained root of the 17.

Risk assessment and treatment modification

Prior to treatment planning, it was essential to complete a thorough risk assessment and plan treatment modifications, which are presented in Table 1.

Dental treatment

The following dental treatment was provided:

- 1.

Preventive advice

- 2.

Non-surgical periodontal therapy

- 3.

Restorations of restorable teeth

- 4.

Root canal treatment of unrestorable teeth

- 5.

Retained root of 17 left in situ.

A multidisciplinary approach was taken to deliver dental treatment. The patient was referred to the dental hygiene and therapy department, and a preventive regime for high caries and periodontal disease risk was initiated in accordance with Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention.10 This consisted of high fluoride toothpaste (sodium fluoride [NaF] 1.1% or 5,000 ppm) to be used twice daily with a soft toothbrush, and NaF 0.05% mouthwash to be used at an alternative time to toothbrushing. Interdental brushes were also recommended. The use of alcohol-free chlorhexidine 0.2% mouthwash was advised as an adjunct when there is increased pain preventing the patient from toothbrushing effectively. NaF 2.26% (22,600 ppm) varnish was applied to all teeth to further reduce the caries risk. At subsequent visits, the patient complained that he experienced mucosal pain with the high fluoride toothpaste. Sodium lauryl sulphate-free toothpaste was recommended to use periodically. The dental therapists undertook non-surgical periodontal therapy and completed restorations of restorable teeth.

As the patient was at a high risk of developing osteoradionecrosis, root canal treatment of teeth with gross caries and/or apical pathology was completed by the SCD team. Unrestorable teeth were subsequently decoronated, root canal treatment provided as required, and glass ionomer cement coverings placed on the retained roots. An oral surgery opinion was sought regarding the management of the 17 retained root, and a best interest decision was made to leave retained roots in situ (17), in view of the high osteoradionecrosis risk.

Follow-up

At subsequent visits, the patient presented with further dental disease. The lower right central incisor (41) had fractured and was tender on palpation. Diagnosis of acute periapical periodontitis was made. Further restorable caries was detected on eight teeth. The retained root of the 17 was causing mild discomfort. However, conservative management with the prescription of antibiotics in the first instance was advised by the oral surgery department. The patient expressed his preference in leaving the root in situ, avoiding a surgical procedure. He was aware of the potential risk of recurrent pain and infection associated with this.

Discussion

It has been recognised for many years that patients diagnosed with HNC should be assessed by the dental team pre-cancer therapy.6 The patient presented in this article attended the SCD department having already completed multiple courses of chemotherapy and high dose radiotherapy, in addition to surgery for HNC. Unfortunately, he had not received a comprehensive oral assessment before his cancer therapy, although this is recommended by national guidelines.6,7 A factor that could have contributed to this may be the lack of a clearly defined dental referral pathway and access to specialist dental care in the head and neck cancer unit where he received his cancer therapy. Urgency of cancer treatment should not preclude dental assessment. However, it is recognised that not all cancer pathways have an integrated dental component, with only 35% of patients receiving pre-treatment dental assessment.11

Although the patient reported that he had access to a primary care dentist and had previously attended yearly, a dental assessment focusing on the risks of cancer therapy had not been undertaken. This resulted in a lack of a coordinated dental intervention before cancer therapy. Additional preventive measures were also not put in place to mitigate the risk of deterioration of oral health due to factors such as xerostomia, reduced oral access and discomfort of the oral mucosa.

Due to the lack of lack of dental care being integrated within the cancer pathway, the patient presented with high dental treatment need, with multiple carious lesions, some of which were unrestorable. Increased caries and periodontal disease are recognised side effects of cancer treatment.12 Changes in saliva composition, lower pH level and xerostomia predispose individuals to caries.13,14 Only irradiated tissues are affected, and the risk of xerostomia is reduced with intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). This technique allows accurate targeting of tumour cells and the ability to spare salivary glands.15 In addition, taste disturbance and high calorie diet with changes in nutritional status may further increase the risk.16 The patient experienced difficulties eating and nutritional intake was supplemented by the use of a PEG. The patient drank high-cariogenic drinks. To reduce these risks, it is vital to have appropriate preventive measures in place, as discussed previously. This should include smoking and alcohol cessation advice to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence.7,10 Dental hygienists and therapists are integral in providing preventive care. The RCS oncology guideline advises that dental hygienists must be part of the wider oncology team and patients should have access to a hygienist during cancer therapy.7

Moreover, the patient had other post-operative complications of cancer therapy which are known to have a significant impact on quality of life.17 In general, there is an increased risk of complications with a higher dosage of cancer therapy,18 as this patient received. Mucosal changes are common, secondary to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.12,19 Mucositis is a short-term complication that resolves several weeks after completion of treatment. In this case, the patient presented with generalised painful atrophic mucosa which is a long-term complication.20 This may have rendered good oral hygiene practices a challenge. The patient attempted to manage this by frequent use of chlorhexidine 0.2% mouthwash; however, this alone was insufficient in controlling the plaque level and in turn dental disease.

Trismus is a common side effect of radiotherapy that may result in challenges in providing dental treatment, especially to posterior teeth.12 Treatment was provided in stages, which was more manageable for the patient. In this case, mouth props were not used to improve oral access, as the patient found them uncomfortable. Instead rolled up gauze swabs were used as required.

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) of the jaw can occur following radiotherapy. The higher the dose, dictated in the Gy, the higher the risk of ORN.12 The patient received 65 Gy in 30 fractions, which is a high dose rendering him more susceptible to ORN. When treatment planning this was taken into consideration and led to the decision of undertaking decoronation and root canal treatment of unrestorable teeth. Moreover, the patient expressed his wishes to monitor the 17, and he was fully aware of the risk of pain and infection. The risks and benefits of the treatment options were discussed at length with the patient to ensure that he made an informed decision.

This case describes some of the orofacial complications of cancer therapy. Earlier dental intervention, with integrated oral assessment at the outset before cancer treatment, may have reduced the extent of dental disease and improved this patient's quality of life. Unfortunately not all cancer pathways have an integrated dental component (restorative, special care, oral surgery, hygiene and therapy) and these patients may present to local general dental practitioners to access dental screening. The role of the general dental practitioner (GDP) is outlined in Table 2.7,21 An appropriate preventive regime should be adopted, with support from dental hygienists/therapists. Regular dental follow-up is essential in reducing further risk of dental disease as well as recognising potential early signs and symptoms of cancer recurrence.

Conclusions

Head and neck cancer incidence rates are increasing, and dental professionals are likely to be involved in managing this patient cohort. Cancer treatment increases the risk of oral diseases, which are mostly preventable. This case illustrates that oral assessment and urgent dental treatment should start before cancer treatment. Patients should have access to the dental team, including hygienists during cancer therapy, with prevention to minimise complications. Post-operative regular dental follow-up should be instigated for monitoring and maintenance. Care should be provided on shared care basis, with collaborative working between GDPs and dental specialists.

References

Mehanna H, Paleri V, West C M, Nutting C. Head and neck cancer - Part 1: Epidemiology, presentation and prevention. BMJ 2010; 341: c4684.

Cancer Research UK. Head and neck cancer statistics. Available at https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/head-and-neck-cancers (accessed June 2019).

Smittenaar C R, Petersen K A, Stewart K, Moitt N. Cancer incidence and mortality projections in the UK until 2035. Br J Cancer 2016; 115: 1147-1155.

Mehanna H, West C M, Nutting C, Paleri V. Head and neck cancer - Part 2: Treatment and prognostic factors. BMJ 2010; 341: c4690.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract: assessment and management in people aged 16 and over. 2016. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng36 (accessed June 2019).

British Association of Head & Neck Oncologists. BAHNO Standards 2009. Midhurst: BAHNO, 2009. Available at https://www.bahno.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/bahnostandardsdoc09.pdf (accessed June 2019).

Royal College of Surgeons. The Oral Management of Oncology Patients Requiring Radiotherapy, Chemotherapy and/or Bone Marrow Transplantation. London: Royal College of Surgeons,2018. Available at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/fds/publications/rcs-oncology-guideline-update--v36.pdf (accessed June 2019).

Restorative Dentistry-UK. Predicting and Managing Oral and Dental Complications of Surgical and non-Surgical Treatment for Head and Neck Cancer: A Clinical Guideline. London: Restorative Dentistry-UK, 2016. Available at https://www.restdent.org.uk/uploads/RD-UK%20H%20and%20N%20guideline.pdf (accessed June 2019).

Osailan S M, Pramanik R, Shirlaw P, Proctor G B, Challacombe S J. Clinical assessment of oral dryness: development of a scoring system related to salivary flow and mucosal wetness. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 114: 597-603.

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2017. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605266/Delivering_better_oral_health.pdf (accessed June 2019).

Health & Social Care Information Centre. National Head and Neck Cancer Audit 2014: Tenth Annual Report. 2015. Available at https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub18xxx/pub18081/clin-audi-supp-prog-head-neck-dahn-13-14.pdf (accessed June 2019).

Sroussi H Y, Epstein J B, Bensadoun R J et al. Common oral complications of head and neck cancer radiation therapy: mucositis, infections, saliva change, fibrosis, sensory dysfunctions, dental caries, periodontal disease, and osteoradionecrosis. Cancer Med 2017; 6: 2918-2931.

Jensen S B, Paedersen A M, Vissink A et al. A systematic review of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia induced by cancer therapies: prevalence, severity, and impact on quality of life. Support Care Cancer 2010; 18: 1039-1060.

Tolentino Ede S, Centurion B S, Ferreira L H, Souza A P, Damante J H, Rubira-Bullen I R. Oral adverse effects of head and neck radiotherapy: literature review and suggestion of a clinical oral care guideline for irradiated patients. J Appl Oral Sci 2011; 19: 448-454.

Butterworth C, McCaul L, Barclay C. Restorative dentistry and oral rehabilitation: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngology Otol 2016; 130 (Spec Iss): S41-S44.

Ray-Chaudhuri A, Shah K, Porter R J. The oral management of patients who have received radiotherapy to the head and neck region. Br Dent J 2013; 214: 387-393.

Carrillo J F, Carrillo L C, Ramirez-Ortega M C, Ochoa-Carrillo F J, Onate-Ocana L F. The impact of treatment on quality of life of patients with head and neck cancer and its association with prognosis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016; 42: 1614-1621.

Andrews N, Griffiths C. Dental complications of head and neck radiotherapy: Part 2. Aust Dent J 2001; 46: 174-182.

Chaveli-Lopez B. Oral toxicity produced by chemotherapy: A systematic review. J Clin Exp Dent 2014; 6: e81-e90.

Elad S, Zadik Y. Chronic oral mucositis after radiotherapy to the head and neck: a new insight. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24: 4825-4830.

Beacher N G, Sweeney M P. The dental management of a mouth cancer patient. Br Dent J 2018; 225: 855-864.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, H., Kumar, N. Dental management of a patient with head and neck cancer: a case report. Br Dent J 227, 25–29 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0464-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0464-7

This article is cited by

-

An audit of dental assessments including orthopantomography and timing of dental extractions before radiotherapy for head and neck cancer

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Effects of ionizing radiation on surface properties of current restorative dental materials

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine (2021)