Abstract

Depression is highly prevalent and easily relapses. Psychological interventions are effective for the prevention of depression relapse. This systematic review and network meta-analysis aimed to compare the efficacy at the same follow-up time points of psychological interventions in depression. We searched PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO via OVID, and the Cochrane Library published up to December 12, 2021, and PubMed up to July 1, 2022. The primary outcome was depression relapse, considering the same time points that were extracted on survival curves or relapse curves. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO, CRD42022343327. A total of 2,871 patients were included from 25 RCTs. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) was significantly better than placebo at the 3 months, the 6 months, and the 9 months at follow-up. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) was significantly better than treatment as usual at the 3 months, the 9 months, the 12 months, and the 15 months at follow-up. CBT was significantly better than placebo at the 21 months and the 24 months at follow-up. Behavioral activation therapy was significantly better than placebo at the 21 months and the 24 months at follow-up. Interpersonal psychotherapy was significantly better than placebo at the 24-month follow-up. All psychological interventions included in the study were significantly better than supportive counseling most of the time. The results were robust in various sensitivity and subgroup analyses. In conclusion, MBCT had a continuous effect in preventing relapse of depression. CBT had the longest but not continuous effect in preventing relapse of depression. The effects of behavioral activation therapy and interpersonal therapy for the prevention of depression appeared late. All psychological interventions included in the study were more effective than supportive counseling. More evidence is needed from large comparative trials that provide long-term follow-up data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a kind of mental disease with symptoms of low mood and lack of experience, interest, or pleasure, and it has the highest global burden in terms of disability years lost [1]. The prevalence of depression is high, with almost one in ten patients on average experiencing depressive symptoms [2, 3], increasing the risk of self-harm and suicide [4,5,6]. Depression is known to relapse at a high rate; evidence indicates that a total estimated 85% of those who recovered from depression will relapse [7]. About 50% of patients experience a relapse or recurrence after recovering from the first episode of depression [8], and patients with five previous episodes of depression are more than twice as likely to relapse compared to those with one-lifetime episodes [9]. Problems concentrating and remembering continue after the depressive episode has subsided and worsens with repeated episodes [10].

Many factors influence relapse, with the more highly recognized causes being residual depressive symptoms at the end of acute treatment and a history of previous relapse [11,12,13]. Increasing numbers of studies have identified lack of social support, age at first presentation, comorbid mental disorders, family history of depression, neurotic personality, and major life events [14,15,16,17,18] as possible risk factors for relapse of depression. Recurrent episodes of depression can have a significant impact on a person’s life. Most patients who experience a relapse of depression feel limited in their productivity and social activities.

Evidence indicates that pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and the combination of the two interventions can prevent relapse of depression [19,20,21]. Psychotherapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), interpersonal psychotherapy, etc., can effectively prevent the recurrence of depression in patients in remission [22,23,24,25,26]. MBCT was more effective than treatment as usual (TAU) for the prevention of relapse of depression and has an advantage over TAU and placebo for the time to relapse of depression [27]. In addition, for patients with three or more previous episodes, MBCT [24] is more effective in preventing relapse. Pharmacotherapy, whether continued or maintained, is a robust treatment for preventing relapse of depression [28].

Previous meta-analyses have analyzed the effectiveness of various interventions to prevent the recurrence of depression. The beneficial effects of CBT alone [29] in reducing the relapse of depression were equal to the beneficial effects of antidepressant medication alone. For short-term follow-up (12 months) [23], CBT was more efficacious than control in preventing depression relapse, however, MBCT and maintenance antidepressant (ADM) medication were not significantly different from each other after 2 years. Zhou et al. [30] showed that various psychological interventions were effective at preventing relapse, but they did not evaluate the effect of psychotherapies on preventing depression at different follow-up durations. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis to explore the long-term effects of different psychological interventions to prevent relapse of depression by extracting data from different follow-up time points.

Methods

Search strategy and selection

In this systematic review and network meta-analysis, we searched PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library databases, and PsycINFO via OVID from the date of their inception to December 12, 2021, and PubMed up to June 30, 2022, for studies that compared psychological interventions for depression relapse prevention. The search term included terms related to depression and depression-like disorders and a great variety of terms related to psychological interventions. The search strategy is shown in Supplementary Table 2. In addition, we examined references from the most current systematic reviews and meta-analyses [27, 30, 31]. Two researchers individually assessed all abstracts, then read full texts and chose relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Discussion and communication with a third author were used to work out any differences before a decision was made. Protocol changes are detailed and presented in Appendix 1. We used common clinical psychotherapy as defined by Cuijpers et al. [31] (detailed definitions in Supplementary Table 4), and all interventions included in the study were classified as CBT, behavioral active therapy, MBCT, interpersonal therapy, supportive counseling, and others, regardless of the delivery format (e.g., individual or group) or treatment medium (face-to-face or online). There were also three groups (treatment as usual, placebo, and antidepression) included for comparison, whose detailed definitions were presented in Supplementary Table 4.

The inclusion criteria were: an RCT in which one arm included a psychological intervention combined with ADM or not; adults (≥18 years) with a diagnosis of depression but not at the acute phase at the time of randomization; survival curves or relapse curves were available for at least 6 months. We excluded studies in which the patient sample included some proportion of patients with bipolar disorder, those in which the participants were elderly individuals only, and those in which participants were male or female only.

Data synthesis and data extraction

We extracted information about publication year; age; sex; total number of participants randomly assigned; number of episodes; follow-up duration; criteria of diagnosis and relapse; all psychological interventions such as CBT, MBCT, interpersonal therapy, behavioral active therapy or supportive counseling, and control interventions including antidepressants, placebo or treatment as usual (definitions in Supplementary Table 4). We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool [32], which assesses potential sources of bias in randomized controlled trials. Two independent researchers extracted the outcome data and assessed the risk of bias, with differences of opinion resolved by consensus after discussion with another author.

The primary outcome was relapse. We extracted data for relapse at eight different time points separately (3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months, 15 months, 18 months, 21 months, and 24 months). We used GetData Graph Digitizer software (version 2.26.0.20) [33] to extract data from relapse curves or survival curves.

Statistical analysis

We performed random-effects network meta-analysis in the frequentist framework (mvmeta and network package) in Stata software (version 15.0) [34]. We used a strict intention-to-treat (ITT) approach to calculate odds ratios (ORs) for binary outcomes and standardized mean differences (SMDs) for continuous outcomes. Both results have been presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Using the method described by Tierney et al. [35], the OR with 95% CI has been estimated using survival plots. The surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) and the probabilities of being the best were estimated to rank the probabilities of each treatment. Better efficacy means a better SUCRA value. A matrix analysis was carried out to test whether the difference in the effectiveness of each pair of psychological interventions with a different SUCRA reached significance. We analyzed the distribution of clinical and methodological characteristics (such as age, sex, sample size, and year of publication) that might serve as impact modifiers across treatment comparisons to evaluate transitivity. Two methods were used to assess network consistency, the extent to which the included studies are statistically and substantively comparable. Using a loop-specific approach, we estimated the inconsistency factor in each loop as the absolute difference between the direct and indirect estimates and truncated the CIs to 0. We used a Z-test to decide whether the inconsistency was significant [36] (i.e., the lower limit of the 95% CI of the inconsistency factor touches 0). Furthermore, the estimated direct and indirect treatment effects and their difference were reported using the side-split method [37], with consistency inferred on the basis of the p-values of the difference. We undertook five prespecified sensitivity analyses for primary outcomes by limiting the analysis to studies reporting the narrowly defined diagnosis of major depression, limiting to studies reporting the narrowly defined relapse of major depression, limiting to studies in which the population was in remission at the time of grouping, and limiting to studies in which the patients were not suffering the first episode of depression, excluding arms that included placebo. To evaluate publication bias, we employed comparison-adjusted funnel plots. We evaluated the confidence in the relative treatment effect estimated in the network meta-analysis for the primary outcome using the confidence in network meta-analysis (CINeMA) [38], implemented in the web application CINeMA [39]. For network meta-analysis, we adhered to the PRISMA guidelines. The systematic review and network meta-analysis were already registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022343327).

Results

Study characteristics

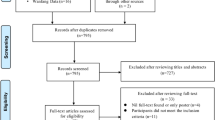

After examining 12,544 abstracts (4192 after removal of duplicates), 56 full-text studies were retrieved for further scrutiny. From these studies, 25 randomized controlled trials with 2871 patients were included in the network meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The aggregated characteristics of the 25 included studies are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Searches identified a total of 2871 publications, with sample sizes ranging from 34 to 424. Study durations ranged from 7 months to 144 months. Thirteen of the 25 studies employed a follow-up period of at least 24 months. All studies had a follow-up duration of at least 12 months except Morokuma 2013 [40] and Perlis 2002 [41]. Twenty-three studies included diagnostic criteria for people with depression from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) or DSM-III. For the majority of studies, the diagnostic criteria for depressive relapse were based on DSM-III or DSM-IV diagnosis of MDD during follow-up.

Details of the risk of bias assessment for the included RCTs are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1 in the Supplement. All studies were judged to have low or unclear risk of bias for the domains random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, or selective reporting. Participant blinding is not possible with group-delivered psychotherapies, therefore, all studies were judged to have a high risk of bias for the blinding of participants and personnel. Three studies were judged to have a high risk of bias for the other biases because participants preferred psychotherapy interventions. Two studies were judged to have a high risk of bias for the incomplete outcome data domain, as only data from participants who completed the trial were included in the analysis.

Network meta-analysis

The network plot at the 9-month follow-up is shown in Fig. 2. It indicated that CBT was the best therapy of those examined and was connected to the nodes of all other monotherapy psychological interventions (except MBCT). Five types of psychotherapy (CBT, MBCT, behavioral activation therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, and supportive counseling) and one combined therapy (CBT plus ADM) were included in all durations of follow-up. The follow-up duration of all kinds of combined therapies was no longer than 18 months, except for CBT plus ADM and supportive counseling plus ADM (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The lines link treatments with direct comparisons in trials. The thickness of the lines corresponds to the number of trials evaluating the comparison. The size of the nodes corresponds to the number of trials investigating the intervention. ADM antidepressant, BA behavioral active therapy, CBT cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT + ADM cognitive behavioral therapy combined with antidepressant, IPT interpersonal therapy, MBCT mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, MBCT + ADM mindfulness-based cognitive therapy combined with antidepressant, PLA placebo, SUP supportive counseling, SUP + ADM supportive counseling combined with antidepressant, TAU treatment as usual.

Twenty-three studies were included at the 3 months follow-up. MBCT (OR, 4.33; 95% CI, 1.06–17.76) and supportive counseling plus ADM (OR, 37.80; 95% CI, 2.66–536.24) showed a significant advantage over placebo. In addition, CBT (OR, 5.45; 95% CI, 1.08–27.49), MBCT (OR, 8.87; 95% CI, 1.08–73.16), MCBT plus ADM (OR, 26.56; 95% CI, 1.31–536.52) and supportive counseling plus ADM (OR,75.99; 95% CI, 2.00–2892.65) showed significant advantage over supportive counseling. However, no psychological intervention showed a significant advantage over ADM (Figs. 3–6; Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Twenty-three studies were included at the 6 months follow-up. MBCT (OR, 4.33; 95% CI, 1.06–17.76) and supportive counseling plus ADM (OR, 37.80; 95% CI, 2.66–536.24) showed a significant advantage over placebo. CBT (OR, 8.00; 95% CI, 1.52–42.23), behavioral activation therapy (OR, 9.50; 95% CI, 1.19–76.09), MBCT (OR, 12.98; 95% CI, 1.52–110.60) and supportive counseling plus ADM (OR, 113.38; 95% CI, 5.09–2525.53) were also significantly better than supportive counseling. No significant difference was found between psychological interventions and ADM (Figs. 3–6; Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Twenty-four studies were included at the 9-month follow-up. MBCT (OR, 3.71; 95% CI, 1.11–12.39) and supportive counseling (OR, 32.45; 95% CI, 2.58–407.80) showed a significant advantage over placebo. All psychological interventions showed a significant advantage over supportive counseling. However, network meta-analysis found that ADM was significantly better than CBT (OR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.01–0.84) (Figs. 3–6; Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Twenty-three studies were included at 12 months follow-up. No significant difference was found between placebo and other interventions. CBT plus ADM (OR, 7.14; 95% CI; 1.03-49.48), CBT (OR, 4.50, 95% CI; 2.03-10.00) and MBCT (OR, 4.01, 95% CI; 1.02-15.80) showed significant advantage over supportive counseling. However, no interventions except CBT plus placebo showed a significant advantage over placebo. Meanwhile, all psychological interventions showed no significant difference from ADM except CBT (OR, 0.12, 95% CI; 0.02-0.73) (Figs. 3–6; eFigure 3 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Twenty studies were included at the 15-month follow-up. No significant difference was found between placebo and other interventions. CBT (OR, 3.81; 95% CI, 1.86–7.80) showed a significant advantage over supportive counseling. Behavioral activation therapy (OR, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.02–9.55), MBCT (OR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.25–11.24) and MBCT plus ADM (OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.32–2.73) showed significant advantage over ADM; however, ADM was found to be significantly better than CBT (OR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.02–0.64). No psychological intervention showed a significant advantage over supportive counseling except CBT (OR, 3.81; 95% CI, 1.86–7.80) (Figs. 3–6; Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Seventeen studies were included at the 18 months follow-up. No psychological intervention showed a significant advantage over placebo; however, placebo showed a significant advantage over ADM (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.38–0.77). Meanwhile, no psychological intervention showed a significant advantage over supportive counseling except CBT (OR, 3.59; 95% CI, 1.78–7.27). Behavioral activation therapy (OR, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.03–10.11) and MBCT (OR, 3.92; 95% CI, 1.28–12.01) showed a significant advantage over ADM, but ADM was significantly better than CBT (OR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.03–0.69) (Figs. 3–6; Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Fourteen studies were included at the 21-month follow-up. CBT (OR, 7.32; 95% CI, 1.72–31.04) and behavioral activation therapy (OR, 4.48; 95% CI, 1.04–19.36) showed a significant advantage over placebo. Behavioral activation therapy (OR, 4.80; 95% CI, 1.30–17.64), MBCT (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.22–2.42), and interpersonal therapy (OR, 7.84; 95% CI, 2.18–28.22) showed significant advantage over ADM; however, ADM was found to be significantly better than CBT (OR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.01–0.48) and CBT plus ADM (OR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.02–0.41) (Figs. 3–6; Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Thirteen studies were included at the 24-month follow-up. Behavioral activation therapy, interpersonal therapy, and CBT plus ADM showed a significant advantage over ADM, however, ADM was found to be significantly better than CBT. Only CBT (OR, 9.84; 95% CI, 1.79–54.15) and behavioral activation therapy (OR, 6.89; 95% CI, 1.23–38.62) showed a significant advantage over placebo. No psychological intervention showed a significant advantage over supportive counseling except CBT (OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.35–7.62) (Figs. 3–6; Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

The funnel plot indicated that there was no publication bias (Supplementary Fig. 4). The transitivity assumption was not violated for any of the potential effect modifiers that were analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 5). Tests of local incoherence at 9-month follow-up time points showed that the percentages for inconsistent loops were within the expected ranges based on the empirical data (three of 15 loops; Supplementary Table 6). The test of incoherence from the node-splitting model showed significant differences between some comparisons in efficacy and acceptability (Supplementary Table 6). The sensitivity analyses did not materially affect the relative treatment effects (Supplementary Tables 7–11). According to CINeMA, confidence in estimates was low to very low for most primary outcomes at 9-month follow-up, meaning that further research is very likely to affect our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate (eCINeMA in the Supplement).

Discussion

To our knowledge, we have undertaken the first network meta-analysis investigating psychological interventions for the prevention of depression relapse at the same follow-up time point. We analyzed psychological interventions reported in 25 randomized controlled trials with patients. MBCT was better than placebo at the 3 months, the 6 months, and the 9 months at follow-up, was better than ADM at the 15 months, the 18 months, and the 21 months at follow-up. CBT was better than treatment as usual at the 3 months, the 9 months, the 12 months, and the 15 months at follow-up. CBT was significantly better than placebo at the 21 months and the 24 months at follow-up, CBT was less effective than ADM at the 9 months, the 12 months, the 15 months, the 18 months, the 21 months, and the 24 months at follow-up. Behavioral activation therapy was better than ADM at the 15 months, the 18 months, the 21 months, and the 24 months at follow-up, was better than placebo at the 21 months and the 24 months at follow-up. Interpersonal psychotherapy was better than placebo at the 24-month follow-up. All psychological interventions included in the study were significantly better than supportive counseling most of the time.

We found that MBCT demonstrated a sustained and stable effect over placebo in preventing relapse of depression early in follow-up (up to 9-month follow-up). Previous meta-analysis has found the same result [24, 27, 42,43,44]. Most randomized trials of manualized MBCT were followed up for less than 15 months, and the only two papers included in our study that reported more than 15 months of follow-up showed no significant difference from the control. More studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of long-term follow-up of MBCT.

CBT is more effective than other psychotherapies for preventing relapse of depression, but the effect is not stable. Prior reviews suggest that CBT may reduce relapse of depression [45]. For short-term follow-up (a 12-week period), no significant advantage was found for CBT over antidepressants [46]. However, other studies have found that CBT was significantly better than antidepressants [47,48,49]. At 1-year follow-up, some studies demonstrated no significant advantage for CBT over other interventions (e.g., continuation of medication and treatment as usual) [50, 51], but other studies found that CBT showed a significant advance over antidepressants [52]. In addition, among patients with five or more previous episodes of depression, CBT was significantly better than treatment as usual [50] and manualized psychoeducation [53]. Antidepressants were found to be significantly better than CBT, it was different from the previous review [30, 45]. The finding that antidepressants were significantly better than CBT differed from previous reviews [54] may explain this result.

The effects of behavioral activation therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy appeared later. This result was similar to those of previous reports [25, 55, 56]. Furthermore, those who continued their study for at least 2 years noted that the majority of recurrences (79%) occurred during the first year of maintenance treatment [55, 57]. It was found shortly after initial recovery is a high-risk time period for relapse [58]. This may explain the late onset of interpersonal psychotherapy and behavioral activation.

Previously, one network meta-analysis by Zhou et al. [30] had been performed to demonstrate the effect of psychotherapy in preventing relapse of depression. They found that most psychotherapeutic interventions, except interpersonal psychotherapy, were significantly better than ADM. We found similar results at an 18-month follow-up and that all psychotherapeutic interventions except MBCT and supportive counseling showed a significant advantage over ADM at a 24-month follow-up. Our results for MBCT were similar to those of a network meta-analysis by McCartney et al. [27] that showed that MBCT was not statistically different from m-ADM, active control condition, and cognitive therapy. The meta-analysis by Zhang et al. [23] showed that MBCT, compared with m-ADM, did not show a significant relapse prevention effect at 24-month follow-up, but for this comparison, only one study was included. This inconsistency might have occurred because we used a different outcome measure and included studies with survival curves or relapse curves. Therefore, the evidence we included was insufficient, and relevant trials need to be repeated to confirm or overturn our findings.

At the 24-month time point, only one psychological intervention (CBT plus antidepressants) was included that showed a significant effect over antidepressants. This was similar to the findings of meta-analyses by Breedvelt et al. [20] and Guidi et al. [59], who demonstrated that psychological interventions added to antidepressants significantly reduced the risk of relapse when compared with antidepressants alone. Another meta-analysis [60] that reviewed studies of time to relapse over 15 months found that the sequential delivery of a psychological intervention during and/or after tapering may be an effective relapse prevention strategy. Our study was based on full follow-up to assess the effectiveness of preventing depression relapse and used data extracted from survival curves or relapse curves for depression relapse to explore the effectiveness of different psychological interventions in preventing depression relapse at the same time points and the change in the effectiveness of psychological interventions in preventing depression relapse during the follow-up period, excluding the interference at the follow-up time.

This study had some limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting our findings. First, the number of studies for some comparisons was too low. In our network meta-analysis, some interventions (e.g., behavioral activation therapy) only included one study, and only two studies of interpersonal psychotherapy were included, leading to thinly connected networks. Second, the study evaluating the psychological intervention of behavioral activation therapy versus cognitive therapy and ADM was conducted in the setting where behavioral activation therapy was first developed, and it is possible that the investigator introduced bias into the study in favor of that modality. Therefore, considering acceptance, there were fewer withdrawals from the psychological intervention groups than from the control group, which may have caused inflated results. Third, we included all patients with depression, no matter how many episodes of depression they had suffered, which may have influenced the results for the effectiveness of MCBT in preventing depression relapse. Finally, because we used a different outcome measure than previous studies, fewer studies were included in this network meta-analysis. Therefore, we could not compare the effects of different antidepressant type, dose, and duration on patient outcomes.

In conclusion, MBCT had a continuous effect in preventing relapse of depression. CBT had the longest but not continuous effect in preventing relapse of depression. The effects of behavioral activation therapy and interpersonal therapy for the prevention of depression appeared late. All psychological interventions included in the study were more effective than supportive counseling. More evidence is needed from large comparative trials that provide long-term follow-up data.

References

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137–50.

Bromet E, Andrade LH, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, de Girolamo G, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 2011;9:90.

Ferrari AJ, Somerville AJ, Baxter AJ, Norman R, Patten SB, Vos T, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and incidence of major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Psychol Med. 2013;43:471–81.

Reppermund S, Ising M, Lucae S, Zihl J. Cognitive impairment in unipolar depression is persistent and non-specific: further evidence for the final common pathway disorder hypothesis. Psychol. Med. 2009;39:603–14.

Bethell J, Rhodes AE. Adolescent depression and emergency department use: the roles of suicidality and deliberate self-harm. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10:53–9.

Hantouche E, Angst J, Azorin JM. Explained factors of suicide attempts in major depression. J Affect Disord. 2010;127:305–8.

Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Endicott J, Coryell W, et al. Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1000–6.

Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:959–85.

Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Lavori PW, Shea MT, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229–33.

Semkovska M, Quinlivan L, O’Grady T, Johnson R, Collins A, O’Connor J, et al. Cognitive function following a major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:851–61.

McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM, Chen Y, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, et al. Predictors of relapse in a prospective study of fluoxetine treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1542–8.

Bech P, Lönn SL, Overø KF. Relapse prevention and residual symptoms: a closer analysis of placebo-controlled continuation studies with escitalopram in major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:121–9.

Pintor L, Gastó C, Navarro V, Torres X, Fañanas L. Relapse of major depression after complete and partial remission during a 2-year follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:237–44.

Hasin D, Liu X, Nunes E, McCloud S, Samet S, Endicott J. Effects of major depression on remission and relapse of substance dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:375–80.

Okasha A, el Akabawi AS, Snyder KS, Wilson AK, Youssef I, el Dawla AS. Expressed emotion, perceived criticism, and relapse in depression: a replication in an Egyptian community. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1001–5.

van Loo HM, Aggen SH, Gardner CO, Kendler KS. Sex similarities and differences in risk factors for recurrence of major depression. Psychol Med. 2018;48:1685–93.

Nöbbelin L, Bogren M, Mattisson C, Brådvik L. Risk factors for recurrence in depression in the Lundby population, 1947-1997. J Affect Disord. 2018;228:125–31.

Wojnarowski C, Firth N, Finegan M, Delgadillo J. Predictors of depression relapse and recurrence after cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Cogn Psychother. 2019;47:514–29.

Guidi J, Fava GA. Sequential combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:261–9.

Breedvelt JJF, Brouwer ME, Harrer M, Semkovska M, Ebert DD, Cuijpers P, et al. Psychological interventions as an alternative and add-on to antidepressant medication to prevent depressive relapse: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2021;219:538–45.

Clarke K, Mayo-Wilson E, Kenny J, Pilling S. Can non-pharmacological interventions prevent relapse in adults who have recovered from depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;39:58–70.

Bockting CL, Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Kuyken W, Dobson K. A lifetime approach to major depressive disorder: the contributions of psychological interventions in preventing relapse and recurrence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;41:16–26.

Zhang Z, Zhang L, Zhang G, Jin J, Zheng Z. The effect of CBT and its modifications for relapse prevention in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:50.

Piet J, Hougaard E. The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1032–40.

Cuijpers P, Geraedts AS, van Oppen P, Andersson G, Markowitz JC, van Straten A. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:581–92.

Brouwer ME, Williams AD, Kennis M, Fu Z, Klein NS, Cuijpers P, et al. Psychological theories of depressive relapse and recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;74:101773.

McCartney M, Nevitt S, Lloyd A, Hill R, White R, Duarte R. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention and time to depressive relapse: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;143:6–21.

Machmutow K, Meister R, Jansen A, Kriston L, Watzke B, Härter MC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of continuation and maintenance treatments for persistent depressive disorder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;5:Cd012855.

Chen H, He Q, Wang M, Wang X, Pu C, Li S, et al. Effectiveness of CBT and its modifications for prevention of relapse/recurrence in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2022;319:469–81.

Zhou D, Zhou X, Lin Q, Wang W, Lv Z, Chen X, et al. Nonpharmacological interventions for relapse prevention in unipolar depression: a network meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:1255–62.

Cuijpers P, Quero S, Noma H, Ciharova M, Miguel C, Karyotaki E, et al. Psychotherapies for depression: a network meta-analysis covering efficacy, acceptability and long-term outcomes of all main treatment types. World Psychiatry. 2021;20:283–93.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. 2011;343:d5928.

Zein H, Tran V, Abdelmotaleb Ghazy A, Mohammed AT, Ahmed A, Iraqi A, et al. How to Extract Data from Graphs using Plot Digitizer or Getdata Graph Digitizer. 2015. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279285765_How_to_Extract_Data_from_Graphs_using_Plot_Digitizer_or_Getdata_Graph_Digitizer.

Chaimani A, Higgins JP, Mavridis D, Spyridonos P, Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PloS ONE. 2013;8:e76654.

Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16.

Veroniki AA, Vasiliadis HS, Higgins JP, Salanti G. Evaluation of inconsistency in networks of interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:332–45.

Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, Ades AE. Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2010;29:932–44.

Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, Papakonstantinou T, Chaimani A, Del Giovane C, Egger M, et al. CINeMA: An approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003082.

Papakonstantinou T, Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, Egger M, Salanti G. CINeMA: Software for semiautomated assessment of the confidence in the results of network meta-analysis. Campbell Syst Rev. 2020;16:e1080.

Morokuma I, Shimodera S, Fujita H, Hashizume H, Kamimura N, Kawamura A, et al. Psychoeducation for major depressive disorders: a randomised controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:134–9.

Perlis RH, Nierenberg AA, Alpert JE, Pava J, Matthews JD, Buchin J, et al. Effects of adding cognitive therapy to fluoxetine dose increase on risk of relapse and residual depressive symptoms in continuation treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22:474–80.

Kenny MA, Williams JM. Treatment-resistant depressed patients show a good response to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:617–25.

Manicavasgar V, Parker G, Perich T. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs cognitive behaviour therapy as a treatment for non-melancholic depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;130:138–44.

Kuyken W, Warren FC, Taylor RS, Whalley B, Crane C, Bondolfi G, et al. Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: an individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:565–74.

Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Dunn TW, Jarrett RB. Reducing relapse and recurrence in unipolar depression: a comparative meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy’s effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:475–88.

Beck AT, Hollon SD, Young JE, Bedrosian RC, Budenz D. Treatment of depression with cognitive therapy and amitriptyline. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:142–8.

Kovacs M, Rush AJ, Beck AT, Hollon SD. Depressed outpatients treated with cognitive therapy or pharmacotherapy. A one-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:33–9.

Simons AD, Murphy GE, Levine JL, Wetzel RD. Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Sustained improvement over one year. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:43–8.

Miller IW, Norman WH, Keitner GI. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of depressed inpatients: six- and twelve-month follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:1274–9.

Bockting CL, Schene AH, Spinhoven P, Koeter MW, Wouters LF, Huyser J, et al. Preventing relapse/recurrence in recurrent depression with cognitive therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:647–57.

Evans MD, Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Piasecki JM, Grove WM, Garvey MJ, et al. Differential relapse following cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:802–8.

Blackburn IM, Eunson KM, Bishop S. A two-year naturalistic follow-up of depressed patients treated with cognitive therapy, pharmacotherapy and a combination of both. J Affect Disord. 1986;10:67–75.

Stangier U, Hilling C, Heidenreich T, Risch AK, Barocka A, Schlösser R, et al. Maintenance cognitive-behavioral therapy and manualized psychoeducation in the treatment of recurrent depression: a multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:624–32.

Mergl R, Allgaier AK, Hautzinger M, Coyne JC, Hegerl U, Henkel V. One-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of sertraline and cognitive behavior group therapy in depressed primary care patients (MIND study). J Affect Disord. 2018;230:15–21.

Reynolds CF 3rd, Frank E, Perel JM, Imber SD, Cornes C, Miller MD, et al. Nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression: a randomized controlled trial in patients older than 59 years. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;281:39–45.

Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, Cornes C, Jarrett DB, Mallinger AG, et al. Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:1093–9.

Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Buysse DJ, Swartz HA, Pilkonis PA, Houck PR, et al. Randomized trial of weekly, twice-monthly, and monthly interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance treatment for women with recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:761–7.

Keller MB, Shapiro RW, Lavori PW, Wolfe N. Relapse in major depressive disorder: analysis with the life table. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:911–5.

Guidi J, Tomba E, Fava GA. The sequential integration of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of the sequential model and a critical review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:128–37.

Breedvelt JJF, Warren FC, Segal Z, Kuyken W, Bockting CL. Continuation of antidepressants vs sequential psychological interventions to prevent relapse in depression: an individual participant data meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:868–75.

Funding

This work was supported by grants awarded by the Major Project of the Department of Science & Technology, Liaoning Province (2019JH8/10300019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GZ and YZ had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: GZ, YZ, and DZ. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: YZ, DZ, XZ, JX, YZ, YY, RG, LJ, and XS. Drafting of the paper: GZ, YZ, and DZ. Critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content: GZ, LL, MM, XZ, and XS. Statistical analysis: YZ, LL, MM, and XZ. Administrative, technical, or material support: GZ. Supervision: GZ and YZ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Zhao, D., Zhu, X. et al. Psychological interventions for the prevention of depression relapse: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry 13, 300 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02604-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02604-1