Abstract

The emergence of genomic data in biobanks and health systems offers new ways to derive medically important phenotypes, including acute phenotypes occurring during inpatient clinical care. Here we study the genetic underpinnings of the rapid response to phenylephrine, an α1-adrenergic receptor agonist commonly used to treat hypotension during anesthesia and surgery. We quantified this response by extracting blood pressure (BP) measurements 5 min before and after the administration of phenylephrine. Based on this derived phenotype, we show that systematic differences exist between self-reported ancestry groups: European-Americans (EA; n = 1387) have a significantly higher systolic response to phenylephrine than African-Americans (AA; n = 1217) and Hispanic/Latinos (HA; n = 1713) (31.3% increase, p value < 6e−08 and 22.9% increase, p value < 5e−05 respectively), after adjusting for genetic ancestry, demographics, and relevant clinical covariates. We performed a genome-wide association study to investigate genetic factors underlying individual differences in this derived phenotype. We discovered genome-wide significant association signals in loci and genes previously associated with BP measured in ambulatory settings, and a general enrichment of association in these genes. Finally, we discovered two low frequency variants, present at ~1% in EAs and AAs, respectively, where patients carrying one copy of these variants show no phenylephrine response. This work demonstrates our ability to derive a quantitative phenotype suited for comparative statistics and genome-wide association studies from dense clinical and physiological measures captured for managing patients during surgery. We identify genetic variants underlying non response to phenylephrine, with implications for preemptive pharmacogenomic screening to improve safety during surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perioperative phenotypes, such as rapid response to drugs administered during surgery, constitute an integral part of medical practice, as the variation in drug response across individuals is a fundamental variable to consider before, during, and after surgery. One such perioperative phenotype is rapid physiologic responsiveness to short acting adrenergic agents administered to treat hypotension during surgery. Prolonged or recurrent episodes of hypotension during anesthesia and surgery are believed to be associated with increased morbidity and mortality [1,2,3,4,5,6,7], thus the use of these adrenergic agents is common. In the case of response to adrenergic agents, although anecdotal evidence has led clinicians to be aware of individual variation in response between patients, the lack of a rigorous replicable and quantitative phenotype prevents population-level comparisons, which may be linked to both genetic and environmental factors.

The past decades have seen tremendous growth in the use of clinical data from the Electronic Health Record (EHR) for the secondary purpose of research [8]. The establishment of EHR-linked biobanks of genomic data provide unprecedented opportunities for the types of translational and implementation research that drive precision medicine [9,10,11]. Much of biobank research has focused on longitudinal data captured at low temporal resolution (i.e., over months or years); for example, chronic disease conditions recorded in the EHR, or BP taken during routine annual outpatient office visits [12, 13]. Thus, most phenotypes observed in this manner are best suited for genomic discovery in the context of chronic (i.e., long-term) medical conditions. In contrast, pharmacogenomics has traditionally focused on the acute response to drugs administered in a controlled environment. There has been limited biobank-based research to date on the influence that genetics may have on the physiologic response to more acute clinical conditions, such as those experienced during surgery or during a hospital admission.

In this study, we focused our investigation on acute response to phenylephrine during the perioperative period. Phenylephrine, a selective α1-adrenergic receptor agonist, is one of the most commonly used agents for the treatment of intraoperative hypotension, with a very rapid onset when given intravenously and a short half-life of 15–20 min. Prior work focused on candidate genes had linked genetic variants in alpha-adrenergic receptors to differential phenylephrine response [14,15,16,17,18]. In addition, polymorphisms in NOS3 [19] and ACE [20, 21] have been linked to heightened vascular responsiveness to phenylephrine. We had previously developed a rich database of high temporal resolution perioperative data extracted from the Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) [22]. We used this database to generate robust phenotypic profiles of acute phenylephrine response during the perioperative period, and linked these phenotypes to genomic data from the multiethnic Mount Sinai BioMe biobank. We explored whether genetic factors could help explain both the individual variability as well as the variation in response seen between individuals of differing ancestry.

Materials and methods

Study population

The BioMe biobank is an EHR-linked biobank of over 60,000 participants, with ongoing enrollment since 2007, from the MSHS in New York City. Participants included in this analysis were recruited between 2007 and 2015, and consent to provide DNA and plasma samples linked to their de-identified EHRs. Participants provide additional information on self-reported ancestry through questionnaires administered upon enrollment. This study was approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s Institutional Review Board. The study population consisted of n = 30,223 consented BioMe participants aged 18 years or older (upon enrollment).

Genomic data generation and QC

All patients were genotyped on the Illumina Global Screening Array through a collaboration with Regeneron Genetics Center. Genotype quality control steps were performed for all BioMe participants and all genotyped variants as described in Belbin et al. [23]. Imputation was performed using the IMPUTE2 software and the 1000 genomes phase 3 reference panel [24, 25]. After QC filtering, a total of 42,246,687 SNPs were available for analysis.

Linking perioperative and clinical data with genomic data

The Department of Anesthesiology maintains a linked database called iGAS that combines procedure-level data, including intraoperative events, duration of surgery, physiologic data, and medication administration data, linked to individual-level data in the BioMe biobank, such as questionnaire, clinical, and genomic data. The architecture and content of iGAS have been previously described [22]. The resulting linked database is a rich resource of high resolution, high quality perioperative data that can be used to generate robust phenotype profiles. Further data parsing included categorization based on ICD-9 procedure codes, using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classification Software (HCUP CCS, REF https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs_svcsproc/ccssvcproc.jsp) to map individual procedures to high level procedure categories (e.g., Digestive System). ICD-9 codes were used as the majority of data were captured prior to October 2015, and further our health care system did not transition to ICD-10 until late 2016. The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was calculated for each patient using administrative ICD-9-CM discharge diagnosis codes and an ICD-9-CM to comorbidity map with revised diagnosis weights [26, 27]. Calculation of the CCI was done using the R package medicalrisk [28]. The initial cohort consisted of 19,685 BioMe participants linked to 55,104 procedures in iGAS. We filtered to include only patients of self-reported African American (AA, n = 4576), European American (EA, n = 5217), or Hispanic/Latino (HA, n = 6805) ancestries for downstream analysis.

Phenotypic modeling

Intraoperative blood pressure (BP) is typically measured either with a noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP) cuff at a frequency of once every 1–5 min, or continuously via invasive arterial line. Arterial line data are recorded as often as once every 15 s. BP measurements outside of normal physiological ranges (30–120 mmHg for diastolic BP, 30–130 mmHg for mean arterial pressure, 60–240 mmHg for systolic BP), as determined by validity flags in the electronic anesthesia record, were excluded as they likely represented measurement artifacts. To derive a phenotype suitable for further analysis, we defined a rapid drug response as the difference in the recorded minimum BP (systolic—SBP, diastolic—DBP, and mean—MAP) within a 5 min period before and the maximum BP in the 5 min period after a bolus of phenylephrine (Fig. 1A). Five-minute before- and after-windows were used to account for the fact that NIBP measurements and recordings are intermittent, as described above, and also that charting of bolus drug administration is often non-contemporaneous. For patients with an arterial line, this meant a measurement within as soon as 15 s before or after the drug dose was used. For patients with an NIBP, the closest reading could be as soon as within 1 min, if the NIBP cycle time was set to its shortest value. In either case (NIBP or invasive pressure monitoring), the longest delay between a bolus dose and a BP reading would be a maximum of 5 min. This ensured that the time relationship between drug administration and BP measurement was reasonably constant across all patients (Fig. 1). The final phenotypic measurement was thus the Δ SBP, DBP, and MAP response to a bolus of phenylephrine, within 5 min of administration.

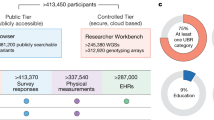

A Data capture schema. The raw phenotype is captured during surgery within a 10 min interval. Additional procedure-related information, as well as general patient-related variables, including genomic data, are combined through the analysis pipeline. B Inclusion/exclusion criteria. From an initial cohort of 19,685 iGAS patients matched to 55,104 procedures, the sequential exclusion criteria and filtering steps reduced the number of patients included in the study to 4317 comprising 1217 African Americans, 1387 European Americans, and 1713 Hispanic/Latinos.

Case inclusion/exclusion criteria

Initial inclusion criteria were all BioMe patients who had undergone anesthesia and received at least one bolus of phenylephrine intraoperatively. A diagram showing all exclusion steps is shown in Fig. 1B. Canceled cases or manually charted cases that had no automated recording of physiologic data were excluded. We also excluded all procedures of short duration and rapid turnover such as colonoscopies and endoscopies where drug bolus administration is known to often be significantly undercharted [29, 30]. Emergency procedures (~1%) were excluded, for several reasons: (1) these cases often involve blood loss and fluid shifts that may have profound effect on intravascular volume and responsiveness to phenylephrine, (2) emergency cases often receive blood products and fluid that are recorded with poor temporal resolution, and (3) charting of drug administration is often compromised and inaccurate during emergency situations. We also excluded procedures in which the patient received any blood transfusion, as blood is a potent vasoactive agent and intravascular volume expander. Additionally, we confirmed the statistical significance of the phenotypic difference between patients having received a blood transfusion and patients who did not receive a transfusion. We computed the correlation between the total amount of crystalloid administered and phenylephrine drug response, and excluded procedures with >5 L of fluid administration charted (~2%).

We performed a preliminary analysis to look for association between the intravenous anesthetic agent propofol and response to phenylephrine. Propofol is known to cause a predictable and often significant decrease in BP and has a similar onset (immediate) and duration (10 min) to that of phenylephrine. Based on the results of this preliminary analysis, we excluded phenylephrine bolus events within 10 min of a bolus dose of propofol. If that phenylephrine bolus was the only bolus the patient received during their procedure, the entire procedure was excluded. For patients with more than one anesthetic/procedure in the data set, only data from the first anesthetic was used. In order to be able to study the interindividual variability and to investigate the genetic basis of the phenotype, only one bolus-response was kept per patient. We kept the Δ SBP, DBP, and MAP associated with the first case and first bolus per patient.

Finally, we excluded BMI outliers (BMI > 100, likely due to data entry error) and procedures on critically ill patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status of 5 (not expected to survive without surgery, n = 9). Such patients usually present with severe organ system derangement and little to no sympathetic reserve. After all patients, procedures, and bolus-response exclusion steps, our cohort contained a total of 4317 patients (1217 AA, 1387 EA, and 1713 HA), among which 3699 were genotyped and passed QC metrics (1082 AA, 1112 EA, and 1505 HA).

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis was used to select covariates to include in the genome-wide association study, with the level of significance set at p value < 0.05. To account for population-level differences, a genetic relationship matrix was calculated and the first ten principal components were included as covariates in the model [31, 32]. The final list of covariates used in the model for the association analysis were age through the use of age-adjusted z-scores, sex, BMI, ASA status, depth of anesthesia, phenylephrine bolus amount, total volume of fluid administered, and the first ten principal components. A SNP genotype association test was performed for all >47 million SNPs either imputed or genotyped directly, with the use of the GENESIS software package: a mixed model with polygenic random effects specified by a genetic relationship matrix was fitted using the fitNullMM function, and said model was then used to perform association tests with the assocTestMM function [31].

Results

Validation of phenotype modeling

After all exclusion steps, our clinical cohort contained a total of 4317 patients (1217 AA, 1387 EA, and 1713 HA). Demographics for the clinical cohort are shown in Table 1. Three thousand, six hundred ninety-nine had genotype data available and passed QC metrics (1082 AA, 1112 EA, and 1505 HA) (Fig. 1B). The average values over the entire cohort for the three different BP response measures were Δ SBP = 17 mmHg (±25), Δ MAP = 14 mmHg (±18), and Δ DBP = 11 mmHg (±14). To validate our method of extraction, we compared the observed drug response in our cohort with published estimates from Schwinn et al. (Schwinn and Reves [18]). Schwinn performed a small clinical trial on phenylephrine drug response in Europeans and reported a Δ MAP of ~15 mmHg after 100 μg bolus of phenylephrine. Our results were similar with an observed Δ MAP of 15.8 mmHg in European Americans. Likewise, for the entire cohort (all ancestries) we observe an average Δ MAP of 13.9 mmHg (Table 2).

Phenotype covariates

We found the presence of blood transfusion to be highly associated with phenylephrine drug response (Supplementary Fig. 5, p value = 5.40e−10). The distribution of total crystalloid administered was skewed and found to be highly correlated with phenylephrine drug response (Supplementary Fig. 6, p value = 4.90e−06). Preliminary analysis demonstrated a large confounding effect of the intravenous anesthetic agent propofol on the phenylephrine signal (p value = 5.764e−05 for a linear regression between Δ SBP and propofol bolus time). There was a significant difference in Δ SBP between patients with a propofol bolus administered within 10 min of a phenylephrine bolus and patients with no propofol bolus or propofol administered within more than 10 min of phenylephrine (Mann–Whitney p value < 0.003). The distribution of total crystalloid administered remained correlated with phenylephrine drug response after exclusion of procedures with >5 L of fluid administered (Supplementary Fig. 6, p value = 4.90e−06). We observed a nominal association between BMI and drug response (p value = 0.03), even after exclusion of outliers likely due to data entry errors. Age and gender were normally distributed in iGAS. Age was associated with drug response (p value = 4.55e−14, Supplementary Fig. 7) so age-adjusted z-scores were used for further analysis. Sex was only nominally associated with drug response (p value = 0.07), thus no exclusions or adjustments were made. ASA status (p value = 3.58e−07), depth of general anesthesia as measured by the Minimal Alveolar Concentration (MAC, p value = 5.23e−10, Supplementary Fig. 8) were associated with drug response in the univariate analysis. CCI was not associated with drug response. We found that phenylephrine response was slightly different between cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and gastrointestinal surgeries, but the association was not statistically significant (p value = 0.6125). The bolus amount of phenylephrine given was not associated with the phenotype; however given the distribution of bolus amounts (Supplementary Fig. 9), the likely non-linearity of the dose–response relationship, and the absence of per patient dose–response curves, we kept phenylephrine bolus amount as a covariate in the model.

Ethnicity impacts BP measures of rapid response to phenylephrine

In a population-stratified analysis, we observed that EA participants demonstrated a significantly heightened rapid response to phenylephrine compared to non-EA patients for all three measures (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The largest difference between populations was observed for Δ SBP (EA Δ SBP = 20 mmHg ± 24; HA Δ SBP = 16 mmHg ± 25; AA Δ SBP = 15 mmHg ± 25), thus this phenotype was used for all downstream analysis. After adjusting for age, sex, BMI, ASA status, phenylephrine bolus amount, depth of anesthesia, total volume of fluid administered, and accounting for self-reported (via validated survey) ancestry, significant differences remained for all three measures between EA participants and HA (Δ SBP, p < 0.032; Δ MAP, p < 0.021; Δ DBP, p < 0.008), and between EA and AA participants (Δ SBP, p < 5.13e−5; Δ MAP, p < 2.1e−4; Δ DBP, p < 3.3e−4).

Genetic discovery

We performed genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for systolic BP response to phenylephrine (Δ SBP), as well as Δ MAP and Δ DBP, across >47 million SNPs either imputed from 1000 genomes project or genotyped directly in 3699 individuals (1082 AA, 1505 HA, 1112 EA) altogether, as well as for each of the three populations separately. Across the three phenotypes (Δ SBP, Δ MAP, and Δ DBP) and the four population groupings (the whole cohort, AA, EA, and HA) we observed genome-wide significant associations (p value < 5e−8) in five different genome regions. Additionally, we observed two genome regions with suggestive associations at p values < 6e−8 and <7e−8 in EAs. Among these seven regions, five of them overlap variants previously associated with routine BP measurements (Table 3, Figs. 3, 4, Supplementary Figs. 1–3). The analysis performed on the HA population with the Δ SBP phenotype identified five adjacent genome-wide significant SNPs which are common in all three studied populations (all MAF > 7%), yet these variants are only associated with a significantly decreased systolic response in the HA population, thereby asserting the importance of ancestry as a factor influencing common alleles’ effect size in the case where these variants are causative. However, as the association is only present in the HA population, an alternative explanation is that the aforementioned SNPs are not causative and tag a variant only present in HA. Notably, these five SNPs are located at 1.27 Mb upstream of rs2761436, a variant previously associated with SBP in a study conducted in a population of mostly non-Hispanic Whites [13] (Table 3, Figs. 3, 4).

A GWAS performed on Δ SBP with the whole cohort. The red horizontal line denotes the genome-wide significance threshold for p-values (5e−8) while the blue horizontal line denotes a p-value threshold of 1e−5. The top SNP is rs145337816, located on chromosome 5, at locus 117211218 (in hg19 coordinates). The minor allele frequency is 0.46%, the imputation info score is 0.909. The association p-value is 2.02e−8. Lambda-gc = 1.0059. B GWAS performed on Δ SBP with European Americans. The top SNP is rs188427942, located on chromosome 5, at locus 122900413 (in hg19 coordinates). The minor allele frequency is 1.16 % in EA (0.57% in the whole cohort), the imputation info score is 0.759. The association p-value is 5.26e−8. Lambda-gc = 0.9976. C performed on Δ SBP with Hispanic/Latinos. The top SNP is rs6657443, located on chromosome 1, at locus 209189265 (in hg19 coordinates). The minor allele frequency is 7.63 % in HA (8.83% in the whole cohort), the imputation info score is 0.948. The association p-value is 7.62e−9. Lambda-gc = 1.0027.

A Patterns of LD around the top SNP rs145337816 for the GWAS performed on Δ SBP with the whole cohort. B Patterns of LD around the top SNP rs188427942 for the GWAS performed on Δ SBP with European Americans. C Patterns of LD around SNP rs147664194 for the GWAS performed on Δ SBP with European Americans. D Patterns of LD around the top SNPs for the GWAS performed on Δ SBP with Hispanic/Latinos.

We performed a gene-based functional annotation analysis of the summary statistics of the GWAS using FUMA and MAGMA [33, 34]. Several genes share a high level of statistical significance across the gene-based analysis performed with the three different phenotypes, the three stratified populations and the joint population analysis. Six genes surpass a gene-based adjusted threshold for significance (Bonferroni adjusted p value < 1e−6) in all analyses: CNTNAP2, previously found to be associated with SBP and DBP in Mexican Americans [35]; MACROD2, associated with DBP in a multiethnic cohort [36]; CSMD1 and WWOX, associated with hypertension in Asian populations [37, 38]; DPP6, which contributes to transient outward current in Purkinje fibers [39]; SORCS2, associated with concentrations of IGFBP-3, a vasodilator [40, 41]. The complete results of the gene-based and gene set analysis are available in Supplementary Table 1.

We identified two subgroups in which the MAF was associated with an attenuated BP response: patients who either had no increase in BP in response to the bolus, or whose BP paradoxically declined after the bolus. The first group of non responders was identified through the analysis performed on the EA population, which identified two rare SNPs, rs188427942 (MAF EA: 1.16%) and rs147664194 (MAF EA: 1.01%) located in or near gene CSNK1G3 (Casein Kinase 1 Gamma 3), in regions previously associated with SBP, DBP, and PP (pulse pressure) [42,43,44,45]. CSNK1G3, which encodes a member of a family of serine/threonine protein kinases that phosphorylate caseins and other acidic proteins, is mostly expressed in fibroblasts [46] (Supplementary Fig. 4). On average, the 22 carriers of both SNPs have a Δ SBP of −9 mmHg (±32). In contrast the rest of the EA samples had an average Δ SBP of 20 mm Hg (±24). The second group of non responders was identified through the analysis performed on the AA population with the Δ DBP phenotype. Intergenic SNP rs146535276 (MAF AA: 0.99%) is located in a 1 Mb genomic region on chromosome 8 previously associated with SBP, DBP, and AT (arterial tonometry) [47,48,49]. On average, the 21 AA carriers of rs146535276 have a Δ SBP of −2 mmHg (±26) mmHg, while the rest of the AA cohort have a Δ SBP of 15 mmHg (±25) (Table 3, Figs. 3, 4, Supplementary Fig. 3). We also observed that carriers of rs145337816, a rare SNP only present in European Americans (MAF: 0.56%) and Hispanic/Latinos (MAF: 0.33%), constitute a small group of potential “super-responders”, i.e., patients with a significantly high response (Δ SBPEA = 37 mmHg (±29) and Δ SBPHA = 53 mmHg (±36)), with the caveat that results obtained on such a small number of individuals might not be reproducible.

We did not find genome-wide significant associations in ACE or NOS3, two genes harboring polymorphisms previously associated with response to phenylephrine, nor in adrenergic receptor genes. In particular, we report an absence of nominal association in our study of the NOS3 polymorphism G894T (p = 0.19−1), previously linked to heightened vascular response to phenylephrine. Another variant previously associated with phenylephrine response, the insertion/deletion polymorphism rs1799752 in the ACE gene did not pass QC filters, and is thus not included in this analysis. Finally, we did not observe significant association at any of the adrenergic receptor genes (ADRA1A, ADRA1B, ADRA1D, ADRA2A, ADRA2B, ADRA2C, ADRB1, ADRB2, and ADRB3), and there was no significant enrichment in association at any gene, when compared with random regions of the genome of the same size. The results of the statistical tests for the most significant locus for ACE, NOS3 and adrenergic receptor genes for each population and each phenotype tested are available in Supplementary Table 2.

Systolic blood pressure genes association

We observed nonrandom enrichment in association (significance threshold set at p < 0.001) with systolic drug response in 165 loci previously reported to be associated with systolic BP in the UK BioBank cohort [50]. These 165 loci are centered around single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) reported as being associated (p < 5e−8) with systolic BP in a genome-wide association study performed on 361,402 individuals of mostly European ancestry [50]. To explore whether the genetic loci underlying SBP as measured in routine clinical visits may impact the Δ SBP response to phenylephrine administration during surgery, we investigated whether these loci were enriched in the GWAS signals. First, we counted the number of times we observed a p value of association less than 10−3 in all 165 regions. Next, we counted the number of times we observed a p value of association <10−3 in 1000 random selections of 165 regions of similar genomic size, in order to generate a distribution of random signal across the genome (Fig. 5). Out of the 165 independent genome regions associated with SBP in the UK BioBank cohort, 150, 139, 99, and 132 regions were associated with Δ SBP in our complete cohort, and in AA, EA, and HA individuals respectively. Alternatively, when randomly selecting 165 regions of the genome, 141.9 (±5.69), 130.4 (±5.41), 87.4 (±8.95), and 120.9 (±7.34) regions are associated with Δ SBP in our complete cohort, and in AA, EA, and HA individuals respectively (1000 random selections were performed). Comparing these random distributions with the ratio of systolic BP regions associated with Δ SBP in the four cohorts allows us to establish p values of 0.096, 0.069, and 0.06 for EA, HA, and AA participants respectively and of 0.093 for the full cohort. These results, albeit not statistically significant, indicate a positive trend of potentially shared genetic architecture underlying both phenylephrine response and systolic BP.

The four plots show the distribution of the number of SNP associations with a p value lower than 1e−3, when randomly selecting 165 genome regions (1000 permutations) for the four different population groups (the whole cohort in black, European Americans in green, African Americans in red, Hispanic/Latinos in blue). The vertical bars correspond to the number of genes out of the 165 genes identified in the UKBB cohort to be associated with systolic blood pressure which obtain a p value lower than 1e−3 when looking for association with Δ SBP in our four cohorts. The 165 systolic blood pressure genes are nominally enriched in association with Δ SBP in European Americans (p value = 0.096), Hispanic/Latinos (p value = 0.069), African Americans (p value = 0.060), and in the whole cohort (p value = 0.083).

Discussion

In the present study, we successfully used extant clinical data recorded during surgery for the secondary purpose of exploring genomic factors underlying rapid response to phenylephrine, a therapeutic used to treat BP. We underscored the importance of defining a rigorous phenotype to represent the dose–response to phenylephrine during surgery. Reassuringly, the results of our derived phenotype closely matched the BP change observed by Schwinn and Reves 30 years ago [18]. This consistency validates both Schwinn’s original results obtained in a small cohort, as well as our contemporary results derived from routine clinical care. Our phenotypic modeling process allowed us to perform population-level comparisons, notably highlighting statistically significant differences across self-reported ancestries. We found that self-identified Europeans had a significantly heightened response to phenylephrine administered intraoperatively compared to other populations. We tested several hypotheses to explain this difference, including, age, gender, body mass index, level of anesthesia, concurrent medications, and co-morbidities (Table 1). None of the aforementioned variables explained the difference in phenylephrine response across populations. Differences in drug response between populations provide evidence that genetic ancestry and/or unmeasured environmental factors could account for the trait variability across populations, as is the case with other drug response or pharmacogenomics phenotypes [51, 52].

Using this derived trait in a GWAS allowed us to discover novel loci in the genome that could explain variability in drug response to phenylephrine. Notably, five out of the seven independent genomic regions harboring SNPs associated with the three derived phenotypes were previously associated with related BP phenotypes. In a gene-based functional annotation analysis of the GWAS results, we linked six genes in these regions to previously reported findings for SBP, DBP, and hypertension. We observed suggestive evidence to support the enrichment of genes previously associated with SBP. This evidence indicates a general shared genetic architecture between systolic drug response and SBP. Conversely, we did not find evidence of significant genetic association at any of the adrenergic receptor genes. While it had previously been observed in small cohorts of patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB that carriers of the G894T polymorphism of NOS3 have a significantly heightened vascular responsiveness to phenylephrine [19], we did not observe this effect in our cohort. We were not able to confirm a similar effect in carriers of the insertion/deletion polymorphism of ACE [20, 21], as this specific variant was not included in our analysis. Taken together, these findings suggest that, on average, the underlying etiology of BP has a larger effect than pharmacogenetic variation on an individual’s response to phenylephrine administered intravenously during surgery

However, our experimental design also allowed us to identify rare variants whose carriers are phenylephrine non responders. For example, there were 22 European American participants (2%) carrying 2 variants and 21 African American participants (2%) carrying a single variant in our study each associated with the absence of response to phenylephrine. Being able to predict non responders to a particular therapeutic prior to surgery based on a small number of variants has important clinical implications, especially in an era of personalized medicine, where the number of patients being genotyped or sequenced grows exponentially. Due to the novelty of the phenotype we developed in this study, we are not able to independently validate this finding in other cohorts, and future studies are needed to replicate this finding and evaluate medical utility. Finally, we observed 851 other non responders (23%) in our study who do not carry these variants, indicating that there could be other genetic and/or nongenetic factors at play.

Our study adds to the existing body of knowledge by significantly increasing the number of sampled individuals and assessing Δ MAP, Δ SBP, and Δ DBP in patients of diverse ancestries, as the extent to which African Americans and Hispanic/Latinos respond to intravenous phenylephrine administration was previously unknown. There are parallels between our study and a recent publication by Zhang et al. but with several important differences [53]. That study analyzed phenylephrine infusions rather than boluses, was limited to patients of European ancestry and did not identify genome-wide significant loci. Conversely, thanks to our study design and multiethnic cohort, we were able to highlight significant differences between the three populations for the derived phenotypes and detect population-specific genome-wide significant loci associated with phenotypes. These findings allow us to discriminate the roles of pharmacogenomics and vascular biology in a novel perioperative phenotype, and demonstrate that genetic determinants underlie individual-level response to phenylephrine administered during surgery.

Limitations

Our approach entails some caveats and should be considered as exploratory science rather than hypothesis-based. Even at the scale of hospital-wide biobanks, the application of stringent sample filtering and removal steps, which are paramount when studying a phenotype measured in the “real-world”, dynamic environment of an operating room, prevents us from reaching sample sizes large enough to replicate this method on less commonly used drugs or to extrapolate a polygenic risk score. It is important to highlight that using only a single response does not allow us to build a dose–response curve for each patient and it is possible that if we had chosen a different bolus to analyze, we would have seen somewhat different results. However, the majority of patients were given the same dose, which is a standard dose used to treat hypotension in the operating room. Furthermore, while we did include depth of anesthesia at the time of the phenylephrine bolus as a covariate, the BP response observed was likely also dependent on the degree of surgical stimulation (or lack thereof) and volume status at the time of the bolus. These variables were not captured and remain as potential unmeasured residual confounders.

Thanks to the diversity of our biobank, our multiethnic study was balanced enough to allow us to observe significant differences in drug response across self-reported population groups. However, given the expanse of our sample set and the inherent statistical limitations of the methods used, genomic signals recorded should be reckoned as potential association indications requiring further downstream analysis rather than definitive assessments of the functional role of genes mentioned, particularly for low frequency variants which have a susceptibility of being false positives. Cardiac output, which is not routinely measured outside of cardiac surgery operating rooms, is a significant residual confounder of the BP response to any pressor. The incidence of congestive heart failure (CHF), which is usually a low cardiac output state, was significantly higher among African Americans in our cohort. It is possible that this is partially responsible for the blunted SBP response we observed in this group, however, a multivariate analysis showed no significant association between CHF and SBP in our cohort. We were able to identify groups of nonresponders carrying rare variants, however given the small number of patients carrying these variants, several potential confounders might be at play, and these results should be considered preliminary until confirmed by further prospective studies.

As biobanks and genomic databases are constantly increasing in size, limitations in sample size will gradually disappear. Moreover, federated datasets and data-sharing across multiple institutions are paving the way toward sample sizes orders of magnitude larger than currently available ones, leading to significant increases in statistical power and precision [8, 54]. Approaches like the one used in this paper, leveraging the union of genomics and extensive clinical data capture, as well as statistical tools borrowed from the field of artificial intelligence to customize treatment, will lead to tailored dosage and anesthetic plans, thereby constituting a true paradigm change in the practice of surgery and making it the next field where patients can expect to benefit from precision medicine.

References

Bijker JB, van Klei WA, Vergouwe Y, Eleveld DJ, van Wolfswinkel L, Moons KGM, et al. Intraoperative hypotension and 1-year mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1217–26.

Charlson ME, MacKenzie CR, Gold JP, Ales KL, Topkins M, Shires GT. Intraoperative blood pressure. What patterns identify patients at risk for postoperative complications? Ann Surg. 1990;212:567–80.

Levin MA, Fischer GW, Lin H-M, McCormick PJ, Krol M, Reich DL. Intraoperative arterial blood pressure lability is associated with improved 30 day survival. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:716–26.

Monk TG, Saini V, Weldon BC, Sigl JC. Anesthetic management and one-year mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:4–10.

Sessler DI, Sigl JC, Kelley SD, Chamoun NG, Manberg PJ, Saager L, et al. Hospital stay and mortality are increased in patients having a ‘triple low’ of low blood pressure, low bispectral index, and low minimum alveolar concentration of volatile anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1195–203.

Vernooij LM, van Klei WA, Machina M, Pasma W, Beattie WS, Peelen LM. Different methods of modelling intraoperative hypotension and their association with postoperative complications in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:1080–9.

Walsh M, Devereaux PJ, Garg AX, Kurz A, Turan A, Rodseth RN, et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:507–15.

Abul-Husn NS, Kenny EE. Personalized medicine and the power of electronic health records. Cell. 2019;177:58–69.

Bowton E, Field JR, Wang S, Schildcrout JS, Van Driest SL, Delaney JT, et al. Biobanks and electronic medical records: enabling cost-effective research. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:234cm3.

Kohane IS. Using electronic health records to drive discovery in disease genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:417–28.

McCarty CA, Chisholm RL, Chute CG, Kullo IJ, Jarvik GP, Larson EB, et al. The eMERGE Network: a consortium of biorepositories linked to electronic medical records data for conducting genomic studies. BMC Med Genom. 2011;4:13.

Dumitrescu L, Ritchie MD, Denny JC, El Rouby NM, McDonough CW, Bradford Y, et al. Genome-wide study of resistant hypertension identified from electronic health records. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0171745.

Hoffmann TJ, Ehret GB, Nandakumar P, Ranatunga D, Schaefer C, Kwok P-Y, et al. Genome-wide association analyses using electronic health records identify new loci influencing blood pressure variation. Nat Genet. 2017;49:54–64.

Amory DW, Grigore A, Amory JK, Gerhardt MA, White WD, Smith PK, et al. Neuroprotection is associated with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists during cardiac surgery: evidence from 2,575 patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;16:270–7.

Flancbaum L, Dick M, Dasta J, Sinha R, Choban P. A dose-response study of phenylephrine in critically ill, septic surgical patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;51:461–5.

Kleine-Brueggeney M, Gradinaru I, Babaeva E, Schwinn DA, Oganesian A. Alpha1a-adrenoceptor genetic variant induces cardiomyoblast-to-fibroblast-like cell transition via distinct signaling pathways. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1985–97.

Oganesian A, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Parks WC, Schwinn DA. Constitutive coupling of a naturally occurring human alpha1a-adrenergic receptor genetic variant to EGFR transactivation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19796–801.

Schwinn DA, Reves JG. Time course and hemodynamic effects of alpha-1-adrenergic bolus administration in anesthetized patients with myocardial disease. Anesth Analg. 1989;68:571–8.

Philip I, Plantefeve G, Vuillaumier-Barrot S, Vicaut E, LeMarie C, Henrion D, et al. G894T polymorphism in the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with an enhanced vascular responsiveness to phenylephrine. Circulation. 1999;99:3096–8.

Henrion D, Benessiano J, Philip I, Vuillaumier-Barrot S, Iglarz M, Plantefève G, et al. The deletion genotype of the angiotensin I-converting enzyme is associated with an increased vascular reactivity in vivo and in vitro. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:830–6.

Lasocki S, Iglarz M, Seince P-F, Vuillaumier-Barrot S, Vicaut E, Henrion D, et al. Involvement of renin–angiotensin system in pressure–flow relationship. Anesthesiology 2002;96:271–5.

Levin MA, Joseph TT, Jeff JM, Nadukuru R, Ellis SB, Bottinger EP, et al. iGAS: a framework for using electronic intraoperative medical records for genomic discovery. J Biomed Inf. 2017;67:80–9.

Belbin GM, Wenric S, Cullina S, Glicksberg BS, Moscati A, Wojcik GL, et al. Towards a fine-scale population health monitoring system. bioRxiv. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1101/780668.

1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73.

van Leeuwen EM, Kanterakis A, Deelen P, Kattenberg MV, Genome of the Netherlands Consortium, Slagboom PE, et al. Population-specific genotype imputations using minimac or IMPUTE2. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:1285–96.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–9.

Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Improved comorbidity adjustment for predicting mortality in Medicare populations. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1103–20.

McCormick P. Medical risk and comorbidity tools for ICD-9-CM Data [R package medicalrisk version 1.2]. 2015. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/medicalrisk/. Accessed 16 May 2019.

Avidan A, Dotan K, Weissman C, Cohen MJ, Levin PD. Accuracy of manual entry of drug administration data into an anesthesia information management system. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61:979–85.

Wax DB, Feit JB. Accuracy of vasopressor documentation in anesthesia records. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30:656–8.

Conomos MP, Miller MB, Thornton TA. Robust inference of population structure for ancestry prediction and correction of stratification in the presence of relatedness. Genet Epidemiol. 2015;39:276–93.

Yang J, Zaitlen NA, Goddard ME, Visscher PM, Price AL. Advantages and pitfalls in the application of mixed-model association methods. Nat Genet. 2014;46:100–6.

Leeuw CA, de, de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, Posthuma D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLOS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004219.

Watanabe K, Taskesen E, van Bochoven A, Posthuma D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1826.

Song YE, Morris NJ, Stein CM. Structural equation modeling with latent variables for longitudinal blood pressure traits using general pedigrees. BMC Proc. 2016;10:303–7.

Kelly TN, Sun X, Brody JA, Gagliano SA, He KY, Hellwege JN, et al. Whole genome sequence analysis of blood pressure phenotypes in the trans-omics for precision medicine and centers for common disease genomics programs. Circulation. 2020;141:A46.

Hong K-W, Go MJ, Jin H-S, Lim J-E, Lee J-Y, Han BG, et al. Genetic variations in ATP2B1, CSK, ARSG and CSMD1 loci are related to blood pressure and/or hypertension in two Korean cohorts. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:367–72.

Yang H-C, Liang Y-J, Chen J-W, Chiang K-M, Chung C-M, Ho H-Y, et al. Identification of IGF1, SLC4A4, WWOX, and SFMBT1 as hypertension susceptibility genes in Han Chinese with a genome-wide gene-based association study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32907.

Xiao L, Koopmann TT, Ördög B, Postema PG, Verkerk AO, Iyer V, et al. Unique cardiac Purkinje fiber transient outward current β-subunit composition: a potential molecular link to idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Circ Res. 2013;112:1310–22.

Kaplan RC, Petersen A-K, Chen M-H, Teumer A, Glazer NL, Döring A, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel loci associated with circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1241–51.

Kielczewski JL, Jarajapu YPR, McFarland EL, Cai J, Afzal A, Li Calzi S, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 mediates vascular repair by enhancing nitric oxide generation. Circ Res. 2009;105:897–905.

Andreassen OA, McEvoy LK, Thompson WK, Wang Y, Reppe S, Schork AJ, et al. Identifying common genetic variants in blood pressure due to polygenic pleiotropy with associated phenotypes. Hypertension. 2014;63:819–26.

Ehret GB, Ferreira T, Chasman DI, Jackson AU, Schmidt EM, Johnson T, et al. The genetics of blood pressure regulation and its target organs from association studies in 342,415 individuals. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1171–84.

Giri A, Hellwege JN, Keaton JM, Park J, Qiu C, Warren HR, et al. Trans-ethnic association study of blood pressure determinants in over 750,000 individuals. Nat Genet. 2019;51:51–62.

Liu C, Kraja AT, Smith JA, Brody JA, Franceschini N, Bis JC, et al. Meta-analysis identifies common and rare variants influencing blood pressure and overlapping with metabolic trait loci. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1162–70.

GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–5.

Evangelou E, Warren HR, Mosen-Ansorena D, Mifsud B, Pazoki R, Gao H, et al. Genetic analysis of over 1 million people identifies 535 new loci associated with blood pressure traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1412–25.

Levy D, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Newton-Cheh C, Wang TJ, Hwang S-J, et al. Framingham Heart Study 100K Project: genome-wide associations for blood pressure and arterial stiffness. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8 Suppl 1:S3.

Salvi E, Wang Z, Rizzi F, Gong Y, McDonough CW, Padmanabhan S, et al. Genome-wide and gene-based meta-analyses identify novel loci influencing blood pressure response to hydrochlorothiazide. Hypertension. 2017;69:51–9.

Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779.

Ramos E, Doumatey A, Elkahloun AG, Shriner D, Huang H, Chen G, et al. Pharmacogenomics, ancestry and clinical decision making for global populations. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014;14:217–22.

Wright GEB, Carleton B, Hayden MR, Ross CJD. The global spectrum of protein-coding pharmacogenomic diversity. Pharmacogenomics J. 2016;18:187.

Zhang Y, Poler SM, Li J, Abedi V, Pendergrass SA, Williams MS, et al. Dissecting genetic factors affecting phenylephrine infusion rates during anesthesia: a genome-wide association study employing EHR data. BMC Med. 2019;17:168.

Stark Z, Dolman L, Manolio TA, Ozenberger B, Hill SL, Caulfied MJ, et al. Integrating genomics into healthcare: a global responsibility. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104:13–20.

Kichaev G, Bhatia G, Loh P-R, Gazal S, Burch K, Freund MK, et al. Leveraging polygenic functional enrichment to improve GWAS power. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104:65–75.

Nielsen JB, Thorolfsdottir RB, Fritsche LG, Zhou W, Skov MW, Graham SE, et al. Biobank-driven genomic discovery yields new insight into atrial fibrillation biology. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1234–9.

Roselli C, Chaffin MD, Weng L-C, Aeschbacher S, Ahlberg G, Albert CM, et al. Multi-ethnic genome-wide association study for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1225–33.

Taylor JY, Schwander K, Kardia SLR, Arnett D, Liang J, Hunt SC, et al. A Genome-wide study of blood pressure in African Americans accounting for gene-smoking interaction. Sci Rep. 2016;6:18812.

Acknowledgements

SW was supported by a Fellowship of the Belgian American Educational Foundation and a WBI. World Fellowship. AOO is also supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) 3U01HG008701-02S1 (eMERGE-PGx). EEK was supported by NHGRI: U01HG009080, U01HG109391, UM1HG0089001; NHGRI/NIMHD; U01HG009610; NHLBI: R01 HL104608; NIDDK: UM1HG0089001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SW, JMJ conceived and designed the experiments; performed the analyses and contributed to the writing of the paper. TJ derived the phenotype. TJ and MAL contributed to the data validation. MAL contributed to the database integration. TJ, MCY, GMB, AOO, SBE, EPB, and OG contributed to the writing of the paper. MAL, EEK conceived and designed the experiments; contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

EEK has received speaker honorariums from Illumina, Inc and Regeneron, Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wenric, S., Jeff, J.M., Joseph, T. et al. Rapid response to the alpha-1 adrenergic agent phenylephrine in the perioperative period is impacted by genomics and ancestry. Pharmacogenomics J 21, 174–189 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41397-020-00194-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41397-020-00194-5