Abstract

Leaf microbiomes play crucial roles in plant health, making it important to understand the origins and functional relevance of their diversity. High strain-level leaf bacterial genetic diversity is known to be relevant for interactions with hosts, but little is known about its relevance for interactions with the multitude of diverse co-colonizing microorganisms. In leaves, nutrients like amino acids are major regulators of microbial growth and activity. Using metabolomics of leaf apoplast fluid, we found that different species of the plant genus Flaveria considerably differ in the concentrations of high-cost amino acids. We investigated how these differences affect bacterial community diversity and assembly by enriching leaf bacteria in vitro with only sucrose or sucrose + amino acids as possible carbon sources. Enrichments from F. robusta were dominated by Pantoea sp. and Pseudomonas sp., regardless of carbon source. The latter was unable to grow on sucrose alone but persisted in the sucrose-only enrichment thanks to exchange of diverse metabolites from Pantoea sp. Individual Pseudomonas strains in the enrichments had high genetic similarity but still displayed clear niche partitioning, enabling distinct strains to cross-feed in parallel. Pantoea strains were also closely related, but individuals enriched from F. trinervia fed Pseudomonas more poorly than those from F. robusta. This can be explained in part by the plant environment, since some cross-feeding interactions were selected for, when experimentally evolved in a poor (sucrose-only) environment but selected against in a rich (sucrose + amino acids) one. Together, our work shows that leaf bacterial diversity is functionally relevant in cross-feeding interactions and strongly suggests that the leaf resource environment can shape these interactions and thereby indirectly drive bacterial diversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In nature, plants are colonized by diverse communities of microorganisms. A balanced microbial community can work as a barrier against biotic and abiotic stress, helping to sustain plant health. On the other hand, failing to establish a normal microbiota can have devasting effects [1]. In-depth descriptive studies have shown that the composition of the plant microbiome depends on many factors [2,3,4], but a significant part of these differences can be attributed to networks of interactions among microorganisms [5, 6]. Besides shaping the microbiome, these interactions play critical roles in maintaining their stability, for example to invaders [6, 7] and could help explain the astounding genetic diversity found among leaf bacteria, even in single plant populations [8]. Given the importance of these interactions, increasing the understanding of how they arise and how diversity influences them, may help develop better strategies to increase plant resilience.

Microbial taxonomic diversity in plant tissues generally follows a gradient from high in roots to lower in leaves, with relatively few taxa that further colonize the leaf apoplastic space as endophytes [1, 9, 10]. This limitation is due to strong constraints on microbial life in the apoplast, including the tight regulation of nutrient resources imposed by plants, presumably in part to limit microbial growth [11,12,13]. Bacterial survival requires at least basic nutrients like carbon and nitrogen. Both sucrose, the primary sugar produced in leaves and amino acids are found in the apoplast [14, 15] and can play important roles in bacterial nutrition and virulence [16,17,18]. However, their availability is unstable and varies both between plant species and within plant species, for example due to diurnal fluctuations [19].

The lack of resources in plant apoplasts is evident when it is considered that an apparently fundamental trait of bacterial leaf pathogens is the ability to mobilize resources with the help of batteries of secreted effector proteins [20, 21]. Non-pathogenic strains (i.e., commensals), however, have fewer adaptations to manipulate plant nutrient availability and therefore are probably more directly reliant on scavenging nutrients [22]. For example, commensal Burkholderia and Agrobacterium express diverse transporters for ribose, xylose, arabinose and urea upon injection into Arabidopsis thaliana leaves [12]. For colonizers like these, metabolic interactions with co-colonizers are likely to play important roles helping them gain nutrition. Specifically, resource limitation increases the likelihood that cooperative or even mutualistic interactions arise, including metabolic cross-feeding [23,24,25]. Such cooperative interactions can also be beneficial by making communities more resilient to fluctuating nutrient availability [26]. Although it is speculated that microbe-microbe interactions in leaves involves nutrient exchange, it is not yet clear how widespread this is and whether cooperation may impact the diversity and establishment of the leaf community [27].

Here, we investigated how the apoplast nutrient environment may influence the arisal of metabolic interactions among bacteria. As a model system, we compared plant species in the genus Flaveria that use different photosynthesis strategies (C3: F. robusta, C4: F. trinervia). Although they are closely related, the evolution of C4 photosynthesis has had direct and indirect effects on traits like leaf metabolism [28, 29] and leaf structure [30]. Thus, we hypothesized that these differences would be likely to affect the arisal of metabolic interactions. To address this question, we used an in vitro community enrichment approach and dissected inter-bacterial interactions at the strain level using metabolomics, genomics and molecular tools. Diverse leaf bacteria have the potential to cross-feed and we found that cross-feeding potential correlated with a more nutrient-poor apoplast environment where survival of individuals is limited. Additionally, we found that metabolic interactions sustain taxonomic diversity across vastly different nutrient regimes and that partitioning of cross-feeding niches can sustain strain-level genetic diversity. Thus, our results suggest that metabolic interactions help bacteria cope with nutrient limitation in host plants and that leaf traits have the potential to shape leaf microbiomes.

Methods

Recovery and metabolomic analysis of leaf apoplast fluid from lab plants

Flaveria robusta, F. linearis and F. trinervia plants were generated from cuttings and grown under controlled conditions at an average day/night temperature of 25 °C/22 °C and a photoperiod of 16 h. Leaf samples were collected over the course of two years: F. linearis was sampled in March 2020 and July 2020; F. robusta was sampled in March 2020, June 2020 and April 2021 and F. trinervia was sampled in March 2020. Each time 2 samples were taken from 2–4 plants of each species. Apoplast fluid was extracted from fully developed leaves by infiltrating them with sodium phosphate (100 mM, pH 6.5) under vacuum in a syringe and recovering it by centrifugation, similar to Gentzel et al. [31]. An infiltration ratio, used later to correct the metabolite peak areas for the dilution that occurred during infiltration, was calculated by dividing the mass of buffer that went into the leaf over the initial leaf weight (Winf − Wini) / Wini. After storage at −20 °C, the samples were subjected to metabolomic profiling via untargeted UHPLC-HRMS. Full details on the apoplast recovery as well as UHPLC-HRMS parameters and data analysis can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

In vitro enrichment and characterization of leaf microbiomes under different nutrient regimes

Enrichment of leaf microbiomes from Flaveria trinervia and Flaveria robusta

Cuttings from F. robusta and F. trinervia were grown in an outdoor garden for two months (Jena, Germany) to allow natural colonization by microorganisms. From each species, fully developed leaves from different plants were collected and pooled together into single samples. Leaves were weighed and washed three times in sterile water to remove dirt and insects. Leaf microbial extracts were prepared by macerating the washed leaves in 1 X PBS + 0.02% Silwet and adding 20% glycerol before storing at −80 °C. About 1000 CFUs (estimated by plating) were pre-cultured in M9 broth with trace elements, vitamins, 11 mM sucrose, 0.2% w/v casamino acids (Difco), 200 mM NH4Cl and 200 µg/mL of cycloheximide to limit eukaryotic growth. After washing cells and standardizing to an OD600nm of 0.3, the pre-culture was used to inoculate three replicates of the two enrichment M9 media supplemented with NH4Cl (33 mM) and either no casamino acids (S-CA) or 0.2% m/v casamino acids (S + CA). For each 48-h passage of the enrichment, the OD600nm was recorded and 5 µL of homogenized enrichment were transferred to a new plate with fresh media. At the last passage, cells were collected for DNA extraction and to prepare glycerol stocks stored at −80 °C. Details of the entire procedure can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Characterization of bacteria in original leaf extracts and in enrichments

To isolate and identify bacteria in the communities, 25 isolates were recovered from the initial leaf extract glycerol stocks and from the glycerol stocks from the twelfth enrichment passage of each condition (150 total – the number of strains were chosen based on feasibility to handle and characterize them). Isolates enriched from F. robusta are named FrLE, Fr-CA or Fr+CA (from leaf extracts or from enrichments without or with casamino acids, respectively) and similarly from F. trinervia, FtLE, Ft-CA or Ft+CA. All isolates were identified by Sanger sequencing of the 16 S rRNA gene. Additionally, bacterial communities in the twelfth enrichment passage were characterized by 16 S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing of the V3-V4 region similar to the two-step approach outlined in Mayer et al. [32] and explained in detail in the Supplementary Methods. Raw data was analyzed in R (version 4.0.4, [33]) using the package dada2 (version 1.18.0: [34] and ordination analyses and figures were created with phyloseq (version 1.34.0; [35]) and vegan (version 2.5-7; [36]). Further details are given in the Supplementary Methods.

Whole genome sequencing was performed on three Pseudomonas sp. (hereafter Pseudomonas) isolates (Fr-CA_5, Fr+CA_3 and Fr+CA_18) and four Pantoea sp. (hereafter Pantoea) isolates (Fr-CA_6, Fr+CA_20, Ft-CA_14 and Ft+CA_17). For this, DNA was extracted, purified and sent to Microbial Genome Sequencing Center (Pittsburgh, USA) for sequencing on the NextSeq 2000 (Illumina) platform at a depth of 300 MBp (~50x for Pseudomonas strains and ~60x for Pantoea strains). The genomes were each assembled using SPADES (3.14.1) and average nucleotide identity (ANI) between the different isolates of each genera was calculated in Kbase [37]. Sequence variants (SNPs and indels) compared to the Pseudomonas siliginis D26 reference genome (assembly accession GCF_001605965.1) were called by mapping the raw sequencing reads from each P. siliginis strain using SNIPPY (version 4.6.0). Further details are given in the Supplementary Methods.

Assessment of the isolates carbon preferences and cross-feeding potential

Production of spent media and evaluation of cross-feeding interactions

After testing all isolates for their growth patterns in the media they were enriched in, for potential auxotrophies and sucrose utilization in presence of other nutrients (see Supplementary Methods for full details on evaluation of the isolates carbon preference) we concluded Pseudomonas strains must have cross-fed from Pantoea and this was investigated in-depth. Pantoea isolates were grown in S-CA (sucrose-only) media and after 48 h, the supernatant was collected by centrifugation and profiled by UHPLC-HRMS. Pseudomonas strains were first precultured in R2A broth and then inoculated in the Pantoea spent media. Growth (OD600nm) and metabolite consumption were recorded after 48 h. The same procedure was followed to assess the cross-feeding potential of several leaf-extract isolates (FrLE and FtLE) towards Pseudomonas.

Competition between Pseudomonas strains while cross-feeding

To evaluate whether fast growing Pseudomonas would outcompete slow-growing strains while cross-feeding from Pantoea, we tagged the isolates Pseudomonas Fr-CA_5 (fast grower) and Pseudomonas Fr+CA_3 (slow grower) with the fluorophores mTagBFP2 and mOrange2, respectively, making them clearly distinguishable for colony counting. We used the delivery plasmid systems pMRE-Tn7-140 and pMRE-Tn7-144 developed by Schlechter et al. [38] (see Supplementary Methods for details). Next, we set three different experiments: in the first one, the tagged strains were combined individually with Pantoea Fr-CA_6 or together in a full mix (both Pseudomonas strains and Pantoea) and inoculated in black 96-well plates containing S-CA media. The fast-growing Pseudomonas isolate was added at half the density of the slow-growing isolate. The plate was incubated in a BioLector I (m2p-labs Beasweiler, Germany) at 500 rpm, 30 °C with humidity control. The controls (each Pseudomonas alone with Pantoea and Pantoea alone) were passaged every 24 h eight times, while the full community was also passaged four times every 48 h. After each passage, samples were taken for CFU counts. Growth of Pseudomonas Fr+CA_3 was monitored by normalizing the red filter channel signal to the biomass signal (more details are given in the Supplementary Methods).

In the second experiment, the two tagged Pseudomonas strains were grown either in monoculture or in co-culture in S + CA over four 24-h passages. This experiment was carried out in clear 96-well plates and incubated in an orbital shaker at 28 °C and 220 rpm. The OD600nm and the fluorescence of the mTagBFP2 and mOrange2 were read in a Tecan Plate Reader at the time of passaging (more details in Supplementary Methods).

For the third experiment, the fast growing strains (Pseudomonas Fr-CA_5:mTagBFP2 and Pseudomonas Fr+CA_18) and the slow growing strains (Pseudomonas Fr+CA_2 and Pseudomonas Fr+CA_3:mOrange2) were combined in all possible pairs and passaged six times on Pantoea Fr-CA_6 spent media. Each strain was also inoculated in monoculture. The incubation conditions, as well as the monitoring parameters for OD600nm and fluorescence, were the same as in the previous experiment. The used media from the 1st passage was centrifuged (5000 rpm for 5 min) and 40 µL of the supernatant were collected for UHPLC-HRMS analysis. The last passage was plated out in LB agar to count CFUs of each strain.

Evaluating link of cross-feeding efficiency and colonization to host species

In-planta testing of Pseudomonas colonization

We tested the ability of two Pseudomonas strains: Fr-CA_5 and Fr+CA_3 to persist in leaves of F. robusta or F. trinervia. For this we inoculated three-week old cuttings grown in potting soil with a washed cell suspension of either Pseudomonas alone or in combination with Pantoea (OD600nm 0.002 of each). The plants were kept in a growth chamber. After 10 days, the leaves which had been inoculated were harvested, surface sterilized first with 2% bleach + 0.02% Triton, followed by 70% ethanol to remove surface bacteria and then washed three times with sterile water. They were then processed to obtain CFU counts/g of leaf. The inoculation was repeated in two fully independent experiments for each species. See Supplementary Methods for full details.

Assessing cross-feeding potential of Pantoea isolates

Following the same procedure as before, Pantoea isolates from all enrichments (Fr + CA, Ft -CA and Ft +CA) were tested for their potential to cross-feed Pseudomonas. Samples of the supernatant were taken after 48 h and subjected to UHPLC-HRMS. To test for inhibitory effects, the spent media of the isolates Pantoea Ft-CA_14 and Pantoea Ft+CA_17 were diluted 1:2 with spent media of Pantoea Fr-CA_6 before growth of Pseudomonas. Full details of these experiments are specified in the Supplementary Methods.

Pantoea and Pseudomonas experimental adaptation

To address whether the nutrient environment affects the cross-feeding interactions, we passaged the two tagged Pseudomonas (Fr-CA_5:mBFP2 and Fr+CA_3:mOrange2) together with either Pantoea Fr-CA_6 or Pantoea Fr+CA_20 on the two different media: S-CA or S + CA. The precultures were prepared and diluted as before, but in this case, 10 µL of the Pantoea suspension (OD600nm = 0.2) were mixed with 5 µL of each Pseudomonas strain (OD600nm = 0.2) and inoculated into 180 µL of the corresponding media. Each community had four replicates. The communities were passaged every 24 h for 25 days. At passage 22, the communities that had been growing in S-CA were transferred to S + CA and vice versa. The OD600nm and fluorescence were measured as before (See also Supplementary Methods).

Results

Leaf apoplasts have plant species-specific availability of potential nutrient resources

To get a first idea of the nutrient environment that leaf colonizing bacteria are exposed to upon entering the apoplast, we extracted apoplastic fluid from three species of Flaveria that each use distinct photosynthesis pathways (Fig. 1A). F. robusta utilizes C3 photosynthesis, F. trinervia utilizes C4 photosynthesis and F. linearis uses an “intermediate” photosynthesis strategy. Compounds were identified as distinct peaks in the untargeted UHPLC-HRMS profiles. Constrained analysis of principal coordinates based on all detected compounds showed an overall clear separation of the plant species (Fig. 1B, PERMANOVA p value = 9.999e-05). Using a targeted approach in parallel, we could quantify amino acids in the extracted apoplastic fluid. Among all detected amino acids, there were significant differences between plant species (Kruskal Wallis p value < 0.05) in all except Glu and Trp. Among the seven amino acids with highest metabolic costs (56) the aromatics (Tyr, Trp and Phe) were significantly more abundant in F. trinervia than in F. linearis and tended to be higher in F. robusta (Fig. 1C). Three of the other four could also be detected (Met, Ile, Lys, not His) and all were significantly higher abundance in F. trinervia than the other two species (Fig. 1C). Thus, the nutrient landscape for potential leaf apoplast colonizers differs between plant species, with some like F. trinervia potentially offering higher amino acid availability.

A Infiltration of leaves and recovery of apoplast fluid wash. B Principle coordinate analysis on Euclidean distances, constrained by plant species and based on all UHPLC-HRMS peaks (area > 1.0E4) in untargeted metabolomics of the extracted leaf apoplast. Points represent replicate sampling at a given time point, ellipses show 95% confidence intervals, numbers indicate the sampling event: N = 20 F. linearis, N = 18 F. robusta, N = 8 F. trinervia. A generalized logarithm transformation (Parsons et al. 2007) was applied to the data. C Amino acids concentrations in the apoplast of F. trinervia, F. robusta and F. linearis. Concentrations were calculated based on an internal standard. Significance values are based on Kruskal Wallis test comparing concentrations between species (ns: p value > 0.05, *p < = 0.05, **p < = 0.01, ***p < = 0.001).

Nutrient and taxonomic diversity shapes microbiome function in Flaveria leaf enrichments

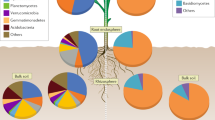

We tested whether and how the nutrient landscape can influence assembly of leaf bacterial communities (Fig. 2A). We enriched bacteria derived from leaves of F. trinervia and F. robusta (Fig. 2B) in a base minimal media with sucrose as the only carbon source and either no amino acids (S-CA) or addition of casamino acids (S + CA) at low levels similar to those previously reported in the apoplast [39]. The final OD600nm was used as a measure of productivity (function) of the enrichments (Fig. 2C). In the S-CA condition where sucrose was the only carbon source, the F. robusta enrichment was slightly more productive than the F. trinervia enrichment. Additionally, enrichments from F. robusta tended to increase their productivity when the potential carbon and nitrogen sources were richer (S + CA), but those from F. trinervia did not.

A Enrichment of leaf bacterial communities in two different minimal media. B Culturable diversity in the leaf extracts used for enrichment from Flaveria robusta and F. trinervia, based on 16 S rRNA Sanger sequencing; n = 25 isolates. C Productivity (final optical density at OD600nm) of the enrichments from each species. Different letters indicate significantly different values (Kruskal Wallis test with FDR adjustment < 0.05, N = 3) (D) Diversity obtained in each enrichment replicate after 12 passages based on amplicon sequencing of 16 S rRNA gene. E Culturable diversity obtained in each enrichment after 12 passages based on Sanger sequencing of 16 S rRNA gene (Three replicates were combined for isolation; n = 25 isolates). The taxonomy color legend corresponds to panels (B, D and E).

To have a broader picture of their taxonomic composition, we conducted amplicon sequencing on the enriched communities (Fig. 2D). Despite diverse bacteria in the original leaves (Fig. 2D), enrichments selected very few taxa, which was not affected by additional resource availability in the form of amino acids. F. trinervia enrichments were fully dominated by Pantoea sp. (Fig. 2D). F. robusta enrichments also contained a high prevalence of Pantoea, but in combination with Pseudomonas (Fig. 2D). To investigate why the productivity differed between the enrichments, we collected 25 random bacterial isolates from the F. robusta and F. trinervia S-CA and S + CA communities (isolates designated as Fr-CA_X, Fr+CA_X, Ft-CA_X or Ft+CA_X, where X is a unique isolate number), identified them taxonomically (Fig. 2E) and tested the growth of each in S-CA and S + CA (Supplementary Table 2). The isolates included multiple individuals of both Pseudomonas and Pantoea, the only genera that were found using 16 S data. In the S-CA community, the fraction of Pantoea was higher than in S + CA (67% vs. 16%, respectively, Fig. 2E). All tested Pantoea isolates could grow on sucrose or amino acids as a sole carbon source (Supplementary Table 2). The fact that productivity did not increase in F. trinervia enrichments with casamino acid addition suggests that another resource must have limited additional growth. All tested Pseudomonas isolates could use amino acids as a sole carbon source (Supplementary Table 2). Thus, the increased productivity in the F. robusta S + CA enrichment suggests that they could make use of the additional resources. Pseudomonas isolates did not use sucrose as a sole carbon source even though they were present in the S-CA (sucrose-only) enrichment (Supplementary Table 2). Therefore, Pseudomonas in this enrichment may have been somehow dependent on Pantoea, which could explain the higher productivity in F. robusta enrichments compared to F. trinervia when sucrose was the only carbon source.

Cross-feeding on diverse metabolites sustains Pseudomonas in the absence of a primary carbon source

We then asked how Pseudomonas isolates survived in the S-CA enrichment if they could not utilize sucrose directly. One possibility is they were auxotrophs and could only grow when amino acids were available in the environment (either in S + CA or provided from Pantoea in S-CA). However, all tested Pseudomonas isolates could grow on glucose without amino acid supplementation (Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that they were not strict auxotrophs.

We tested whether Pantoea produced other metabolic by-products that Pseudomonas could grow on (Fig. 3A). Indeed, all Pseudomonas isolates from the sucrose-only enrichment (Pseudomonas Fr-CA) could grow on spent media of a Pantoea isolated from the same enrichment (Pantoea Fr−CA_6, Fig. 3B). To determine what Pseudomonas consumed, we performed untargeted metabolomics on the spent media before and after growth of three Pseudomonas isolates and considered metabolite peaks to be consumed if their area was strongly reduced (log2FC < −2, FDR < 0.05). With this strict cutoff, we detected uptake of between 23–25 metabolites by each strain, including 2-hydroxybutyric acid, hypoxanthine, spermidine and, in one of the isolates, alanine (Supplementary Table 3). This indicates a complex metabolic dependency of Pseudomonas on Pantoea in the sucrose-only enrichments. We did detect trace levels of glucose and/or fructose in the Pantoea spent medium (hexoses are indistinguishable with this method), but they were not significantly taken up (log2FC = −0.85, p value = 0.36 on average, not shown).

A Procedure to obtain Pantoea (Pa) spent media and evaluate its potential to support Pseudomonas (Ps) growth. B Growth of Ps isolates from the Fr-CA enrichment on Pa Fr-CA_6 spent medium. Significance values are based on a t-test comparing growth in S-CA and in Pa Fr-CA_6 spent medium (ns: p value > 0.05, *p < = 0.05, **p < = 0.01, ***p < = 0.001, N = 3). C Growth curves of two Pseudomonas isolates (Ps Fr-CA_5 and Ps Fr+CA_3) over the course of 24 h on Pa Fr-CA_6 spent medium. Each data point shows the mean of three replicates and the corresponding standard error. OD600nm refers to optical density measured at 600 nm.

Several isolates from the original leaf extracts (FrLE and FtLE) could also feed Pseudomonas. The growth on Bacillus FrLE_12 spent medium, for example, was especially high, even compared to growth on Pantoea spent medium (Supplementary Fig. 1). Metabolomic analyses suggested that Pseudomonas may utilize a diverse array of metabolites from this isolate (log2FC < −2, FDR < 0.05) with little or no overlap with compounds utilized from Pantoea spent media (Supplementary Table 4). None of the taxa with potential to cross-feed Pseudomonas were found in the enrichments, probably due to their lower growth rate in sucrose, when compared to Pantoea (Supplementary Fig. 1). Overall, these results suggest that when competition for sucrose dominates dynamics, Pseudomonas will be limited in cross-feeding partners but otherwise may be able to persist by feeding on exudates of diverse leaf bacteria.

Diverse plant-derived Pseudomonas strains cross-feed in parallel from Pantoea

In the S-CA enrichment, Pseudomonas survived exclusively by cross-feeding on diverse resources from Pantoea exudates, but in the S + CA enrichment, it would have been able to either cross-feed or utilize amino acids or both. Therefore, we hypothesized that multiple Pseudomonas strains may exist to optimally utilize this niche diversity. Indeed, we observed that two Pseudomonas isolates displayed distinct growth phenotypes on Pantoea spent medium. Pseudomonas Fr-CA_5 grew earlier and reached maximum OD600nm faster compared to Pseudomonas Fr+CA_3 (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 2a). A correlated phenotype was observed in R2A medium, where only the slower cross-feeder switched to more rapid growth when supplemented with vitamins that were present in the enrichment medium (Supplementary Fig. 2b). We predicted that in the S-CA enrichment where cross-feeding was required, faster cross-feeders would outcompete slower ones to dominate the mix, while the more diverse nutrient conditions in the S + CA enrichment would result in a more balanced mix. However, when we checked the phenotype across all Pseudomonas isolates, we found that the strains were in similar ratios in both enrichments (Supplementary Fig. 2c, X2 p = 1).

To test whether faster and slower-growing strains could simultaneously cross-feed from Pantoea, we labeled the slow and fast cross-feeder (Pseudomonas Fr+CA_3 and Pseudomonas Fr-CA_5) with fluorescent tags, which did not alter their growth patterns on Pantoea spent media (Supplementary Fig. 3a). We then combined the strains and grew them directly with Pantoea Fr-CA_6 in sucrose-only media (Fig. 4A). Although the fast cross-feeder was inoculated with only half the cells as the slow cross-feeder (see Supplementary Methods), they were approximately equivalent within 48 h (Supplementary Fig. 3B). However, neither strain overtook the other after four 48 h or eight 24 h passages (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c, raw signals provided in Supplementary Fig. 4). In the 24 h passages, the slow grower did reach higher levels with Pantoea alone than it did together with the fast grower (Fig. 4B), consistent with a hypothesis of partially overlapping niches. Total biomass was higher when Pantoea was with Pseudomonas than alone, similar to productivity observations in the original enrichments (Supplementary Fig. 4). Interestingly, the strains could also persist together in the more complex S + CA media without Pantoea (Supplementary Fig. 5).

A Passaging of tagged Ps strains along with Pa Fr-CA_6 on S-CA medium. B Signal of Ps Fr+CA_3:mOrange2 fluorescence normalized by the biomass signal in either co-culture with Pa Fr-CA_6 or in the full community with Pa Fr-CA_6 and Ps Fr-CA_5:mTagBFP2. C Each Pseudomonas strain was passaged either alone or in pairs with each other on Pa Fr-CA_6 spent medium. D, E Taken up metabolites from Pa Fr-CA_6 spent media by each Ps strain when grown in monoculture. Only metabolites with significant uptake are shown (log2 FC < −2, FDR < 0.05). In the heatmap, each column represents a different repetition (N = 6 for each strain). The strains and peaks have been clustered by Euclidean distance. The yellow bars on the right indicate the area (log10) of the peak in the spent media of Pantoea Fr-CA_6 before growth of the Ps. The information of each peak ionization mode, retention time, m/z value and putative annotation) is given in Supplementary Table 6. The order of the peaks shown in the heatmap matches exactly the order of the peaks in the Table.

Differential niches is also supported in genetic analysis of two fast-growing and one slow-growing strain. All were identified as P. siliginis and shared 99.98 to 99.99% ANI (Supplementary Table 5). Aligned to the closest reference Pseudomonas genome, they shared about 97,000 sequence variants with only a few hundred unique to any one genome (Supplementary Fig. 6). Among unique and potentially disruptive variants in each strain, many were in genes likely to influence nutrient acquisition, including porins and carboxylate, sugar and peptide transport proteins (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Methods). Thus, we reasoned that the strains must have unique nutrient niches whereby fast-growing strains can dominate only some resources, reducing the growth of the slow-growers when they are together, but the slow-growers can persist because they also use unique resources.

Niche differentiation among distinct Pseudomonas strains maintains diversity during cross-feeding

To test whether and how Pseudomonas strains exploit complementary niches, we cultured the two labeled Pseudomonas (Fr-CA_5 and Fr+CA_3) and two additional fast and slow growing isolates (Pseudomonas Fr+CA_18 and Pseudomonas Fr+CA_2, respectively) individually and in all possible pairs in Pantoea spent media (Fig. 4C) and evaluated metabolite uptake (niches) and growth patterns. The pattern of metabolite uptake by the strains growing alone was consistent with partially overlapping niches. Several significantly taken up metabolite peaks were shared by all four isolates (common niches) and each also significantly depleted unique sets of metabolite peaks (unique niches) (Fig. 4D, E and Supplementary Table 6). When grown in pairs (Supplementary Figs. 7–12), most of the common niches and some of the unique niches were maintained, further supporting partially overlapping niches. However, new compounds were also taken up, suggesting some cooperative niche exploration. Similar to previous results (Supplementary Table 3), the annotated peaks matched to purines and pyrimidines and to amino acids Trp and Ile/Leu in some combinations (Supplementary Table 6). Over 6 24-hr growth cycles, growth of individual tagged strains was reduced in co-cultures compared to monocultures (based on both fluorescence signal and CFU counts, Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14) but both strains in co-cultures successfully persisted, further supporting a lack of competitive exclusion. Notably, Pseudomonas Fr+CA_2 alone or in co-culture had lower total growth (CFUs) than other combinations (Supplementary Fig. 14). This was apparently not because of inhibition, since growth of other strains with Fr+CA_2 spent media was rather promoted (Supplementary Fig. 15). A likely explanation is that Fr+CA_2 inefficiently used some limiting resource thereby reducing growth of itself and co-colonizers. Regardless, this further highlights the extent of Pseudomonas commensal strain diversity.

Cross-feeding is selected for in a leaf nutrient-dependent manner

Two additional lines of evidence suggested that the plant nutrient landscape could actively select on cross-feeding interactions. First, F. robusta and F. trinervia leaves were inoculated with a slow- or a fast-growing Pseudomonas with or without a partner Pantoea strain and endophytic growth was measured (Supplementary Fig. 16a). Alone, each of the two Pseudomonas strains successfully colonized F. robusta leaves only occasionally, but consistently colonized F. trinervia leaves at high levels (2-sided t-test, p value = 0.06 and 0.05, respectively). We did not observe differences in Pseudomonas colonization when it was inoculated together with Pantoea, but this is likely due to very variable colonization success (Supplementary Fig. 16a). The inability of a commensal to colonize the relatively less nutrient-rich F. robusta alone could increase possible dependence on partners. Second, we found among four characterized Pantoea isolates (one from each enrichment) a gradient in their ability to feed Pseudomonas corresponding to the richness of the origin plant and the enrichment condition. Pantoea from F. robusta fed Pseudomonas best (Fr-CA better than Fr+CA) while Pantoea from F. trinervia supported Pseudomonas hardly or not at all (Supplementary Fig. 16b). Additional analyses suggest that differences are likely due to specific exudates, not antagonistic traits (Supplementary Note). The cross-feeding differences between the Pantoea strains do not correlate to their genetic relatedness: The two Pantoea Fr strains that best support Pseudomonas growth shared only ~81% ANI, but Pantoea Fr-CA_6 and the poor cross-feeding Pantoea Ft isolates share ~98.6% ANI (Supplementary Table 7), consistent with good cross-feeding emerging as a convergent trait in Pantoea in F. robusta.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that the cross-feeding interaction can be selected on by the nutrient environment by evolving two communities across 25 24-hr passages (the tagged P. siliginis Fr-CA:5mBFP2 and P. siliginis Fr+CA_3:mOrange2 both together with either Pantoea Fr-CA_6 or Pantoea Fr+CA_20) in two contrasting nutrient environments (S-CA where cross feeding is required or S + CA where it is not necessarily needed) (Fig. 5). At the 22nd passage, the evolved communities were switched to the opposite environment for 4 cycles. Thus, we obtained two outputs: (1) How growth of the Pseudomonas strains with Pantoea changed (based on fluorescence over the 25 cycles) and (2) How changes affected growth in the other environment (based on fluorescence after switching). (Fig. 5 and see additional details in Supplementary Notes and raw growth data in Supplementary Fig. 19). Pseudomonas growth could change due to adaptation of either Pantoea or Pseudomonas or both, so here we refer just to interaction fitness.

A Passaging of the two tagged Pseudomonas (Ps) strains with either Pantoea (Pa) Fr-CA_6 or Pa Fr+CA_20 on S-CA or S + CA medium. The red vertical line marks passage 22, when the communities were switched to the opposite media to evaluate the effects of their adaptation. B Fluorescence signals of PsFr-CA_5:mTagBFP2 and Ps Fr+CA_3:mOrange2 detected in the communities. Passage 1 naïve strain: Fluorescence intensity of the strain at the beginning of the experimental adaptation, Passage 22 evolved strain: Fluorescence intensity after 22 passages in the experimental adaptation right before switching media. Comparison of Passage 1 naïve and Passage 22 evolved, show changes in strain fitness over the experimental adaptation. Evolved strain after the switch of media: Fluorescence intensity after the evolved community was switched to the other nutrient condition and allowed to equilibrate for 4 passages. Naïve strain: Fluorescence intensity of the naïve strain in the media that the evolved strain was switched to. Comparison of evolved strain after the switch and the naïve strain shows how adaptation in one nutrient condition affected fitness in the other one. Significance values are based on t-tests comparing the fluorescence intensity between Passage 1 and Passage 22 (evolving media) and the evolved and naïve strains in the switch media. ns: p value > 0.05, *p < = 0.05, **p < = 0.01, ***p < = 0.001, N = 4.

Although each Pantoea was always simultaneously evolved together with two Pseudomonas strains, each interaction clearly followed distinct paths (Fig. 5B). The Pseudomonas Fr-CA:5mBFP2 interaction generally fit our hypothesis for how environment should select on cross-feeding. When evolved in the -CA environment, the cross-feeding interaction exhibited either no change or increased (with Pantoea Fr-CA_6 and Fr+CA_20, respectively) and this came at a cost to fitness in the +CA environment. When evolved in the richer +CA environment, fitness did not change or decreased only slightly (with Pantoea Fr-CA_6) over 25 cycles, but the cross-feeding interaction significantly degraded (evidenced by lower growth of the evolved strain after the switch compared to the naive strain). The Pseudomonas Fr+CA_3:mOrange2 interaction, on the other hand, evolved in a way that was very dependent on the Pantoea isolate. With Pantoea Fr-CA_6, fitness increased over the experiment in both environments (3/4 replicates in −CA and 4/4 replicates in +CA) apparently because fitness was coupled across the environments (evolved replicates that grew better in one environment also grew better in the other environment after switching). With Pantoea Fr+CA_20, fitness decreased over the course of the experiment (3/4 replicates in −CA and 4/4 replicates in +CA) with evolved fitness in each environment again strongly correlated to fitness after the switch between environments. Together, these results demonstrate a more complex but consistent story of selection: Selection for cross-feeding depends on amino acid richness for some strains, while for others it is independent of richness but highly dependent on the cross-feeding partner.

Discussion

Leaf bacteria play important roles in protecting plants from pathogens and stress via a variety of different mechanisms, so there is broad interest in understanding the factors that shape their diversity and abundance [40]. It is increasingly clear that interactions between microbial colonizers play major roles in community structuring, whereby the presence of specific microorganisms can drastically alter leaf communities [5]. However, the complications of studying microbe-microbe interactions in-vivo in leaves severely limits our understanding of the types of interactions that are important. To overcome this, we used in vitro enrichment of leaf bacteria under defined nutrient regimes and could demonstrate that leaf bacteria interact with one another via metabolic cross-feeding. This supports previous work that showed that pervasive cross-feeding is possible between leaf-derived bacteria [41] and that it can explain how a surprising diversity can subsist on single carbon sources. Our work additionally showed that cross-feeding can support bacterial taxa who have no direct utilizable carbon source and that in this case, they can survive by utilizing only secreted or leaked metabolites from diverse bacteria. We also showed that environmental conditions relevant in plants can exert selection pressures on cross-feeding interactions in bacterial strain-dependent ways.

The cross-feeders in our enrichments consistently were only Pantoea and Pseudomonas. This was surprising to us, since in previous studies, the diversity of cross-feeding taxa enriched on single carbon sources was high due to promiscuous cross-feeding interactions [41, 42] and because of our finding that multiple other bacterial taxa that we isolated from leaves could have fed Pseudomonas. The most likely explanation is simple resource competition. Pantoea grew much faster than other leaf isolates on sucrose, allowing it to become the sole feeder of Pseudomonas. Pseudomonas also grew rapidly on Pantoea spent medium and could have thereby outcompeted others for key resources. Our results do not necessarily mean that cross-feeding partners would be this restricted in leaves. In contrast to the well-mixed and homogeneous in vitro enrichment environment where competition would dominate dynamics, the leaf apoplast is highly compartmentalized and heterogeneous [43]. Additionally, most endophytic commensal bacteria in leaves reach only low colonization density [44]. These factors would decrease the importance of resource competition and thereby diverse taxa would be able to establish a niche consuming primary plant-derived resources and Pseudomonas or others could establish to take up leaked metabolites. Therefore, cross-feeding interactions in leaves can potentially arise between taxonomically much more diverse members than what we observed in enrichments.

It is important to note that our findings that bacterial diversity is relevant for metabolic interactions among very common leaf bacteria is based on a culture-dependent approach and a limited set of isolates. While such culture-dependent work is critical especially given technological barriers that limit our ability to directly observe metabolic interactions in leaves, it also means that we cannot yet fully weigh the relative importance of metabolic or other (e.g., competitive) interactions among our isolates or especially uncultivated microbes. On the other hand, culture independent techniques and modeling can help provide some insight into the relevance of such interactions. Generally, inference of inter-bacterial interactions in leaves based on culture-independent taxa correlations has suggested extensive negative interactions, but recent improvements that utilize abundance information suggests that positive interactions have probably been underestimated [44]. Similarly, experimental results suggest frequent positive interactions among co-colonizing leaf bacteria [45, 46]. This might seem unlikely, since ecological models have predicted that cooperative interactions can destabilize microbial communities and that competition should therefore benefit hosts [47]. However, the instability in these models is caused by strong species dependencies that can easily be interrupted. In contrast, cross-feeding among leaf bacteria seems to involve weak coupling and high promiscuity.

This type of cross-feeding involving promiscuous interactions could even benefit host plants by stabilizing microbiomes to invasion if cross-feeding networks are redundant enough to leave few resources for invaders [48]. Additionally, apoplast nutrients are important regulators of pathogen virulence, so full occupation of resources by cross-feeding could directly limit damage caused by them even if they successfully invade [49]. This could explain, for example, how Pantoea protects crops from pathogenic P. syringae by decreasing its virulence without eliminating it from the leaf microbiome [50]. Additionally, cross-feeding would be beneficial if it allows bacteria to establish who can, upon invasion, switch to competitive behaviors that protect plants, such as antibiotic production [51]. Therefore, more thorough investigations into the role of cross-feeding in interactions between leaf bacteria and pathogens and its general role in shaping and stabilizing co-colonizing leaf microbiota are needed, including dissection of how metabolic networks arise from host resources through the microbiome.

The three Pseudomonas siliginis isolates we sequenced were genetically similar with ANI of ~99.98% to 99.99% and ~97,000 shared SNPs against the most similar P. siliginis reference genome. While more study is needed to understand this diversity, it appears to be functionally relevant. The sequenced strains had distinct cross-feeding niches with only partially overlapping metabolite uptake profiles, making it possible to cross-feed in parallel despite different growth rates. In addition, two of the strains each showed clearly distinct patterns of adaptation when evolved with Pantoea in two nutrient environments. This diversity must have originated in the original leaf communities since the phenotypes appeared both in sucrose-only enrichments where cross-feeding was required and in enrichments with amino acids as additional resources. Similar levels of diversity were previously found in leaf-associated Pseudomonas viridiflava, where a single OTU (99% 16 S rRNA gene sequence similarity) harbored at least 82 distinct strains (99.9% genome identity), with clearly different host interaction phenotypes [8]. Commensal Sphingomonas bacteria were also shown to exhibit extensive diversity in the presence of secretion systems likely relevant for microbe-microbe interactions [52]. Given that diverse leaf bacteria from multiple plant species have been shown to readily engage in cross-feeding [41], our results strongly suggest that leaf bacterial genetic diversity has important functional relevance for inter-bacterial metabolic interactions in leaves and probably wherever they persist. Since nutrition plays key roles in virulence [53, 54], it also raises the intriguing question of whether interactions like cross-feeding may ultimately influence interactions with hosts.

Pantoea isolates also exhibited interesting and surprising functional diversity. Those from F. robusta enrichments, where cross-feeding occurred, fed Pseudomonas better than those from F. trinervia enrichments, probably by producing more of key metabolites. However, two “good” cross-feeders enriched from F. robusta were only distantly related (81% ANI), consistent with inter-species differences [55] compared to 98–99% ANI between good and bad cross-feeders. This result is consistent with the F. robusta environment selecting for Pantoea with increased metabolite secretion, benefitting cross-feeders. This agrees with in-planta data, where individual bacteria persisted in F. trinervia leaves alone at higher levels than in F. robusta, possibly due to relatively lower levels of key nutrients like amino acids methionine, isoleucine, lysine and valine. Except for the aromatic amino acids, methionine, isoleucine and lysine are three of the four biosynthetically highest-cost amino acids (together with histidine, [56]. The availability of these amino acids could also directly affect exchange of the diverse metabolites we observed here. For example, cross-fed purines guanine and hypoxanthine are connected to methionine via the THF cycle. Thus, differences in the apoplast metabolite landscape could alter selection for traits underlying cross-feeding. Indeed, experimental evolution of cross-feeding interactions in contrasting nutrient environments confirmed that the nutrient environment and the specific cross-feeding interaction determine the adaptive path followed by the strains.

In extreme cases, increased metabolite secretion could result from evolution of reciprocal cross-feeding between Pantoea and Pseudomonas specifically, which can in turn lead to strong co-adaptation [23]. However, this seems unlikely in leaves since conditions including compartmentalization, low bacterial density and high bacterial diversity are likely to make interactions between specific taxa transient, decreasing the likelihood that reciprocal cross-feeding will arise [57]. Thus, if more metabolite secretion is a beneficial adaptation in the F. robusta apoplast environment, it is more likely because Pantoea derives benefits from cross-feeding with diverse taxa rather than Pseudomonas alone.

It is important to note that our results were based on a single set of enrichments from Flaveria plants and therefore represent only a sliver of the interactions that probably happen in a more diverse leaf microbiome and across more diverse host plants. However, given the clear evidence that microorganisms influence one another’s colonization patterns in leaves [5, 6] and the promiscuity of cross-feeding among leaf bacteria, it seems highly unlikely that the vast genetic diversity and stable phenotypes known to exist among leaf bacteria [8] only developed in response to interactions with hosts. Whether the most important interactions shaping this diversity are cooperative metabolic interactions or some other interactions type remain to be seen and this will be an important future avenue of research. However, our results that nutrient differences that are relevant in host plants can drive divergent adaptive cross-feeding responses in closely related bacterial strains add weight to the argument that metabolic interactions may plant important roles.

The apoplast is together with the roots a critical site of host interaction with microbes. While it is not yet clear why some amino acids and other metabolites differ strongly between Flaveria species, one possibility is their different photosynthesis mechanisms. Evolution of C4 photosynthesis in Flaveria has had diverse effects. For example, higher glutathione turnover in sulfate assimilation [28] has led to higher cysteine levels in F. trinervia leaves. While we could not reliably quantify cysteine, it is the direct precursor to methionine, which was significantly elevated in F. trinervia apoplast. Thus, links between photosynthesis and apoplast metabolites are plausible. This is reminiscent of roots, where the exudate nutrient landscape is key to shaping microbial communities [58, 59] and differs between different plant species [60, 61]. Our results strongly suggest that apoplast exudates influence the arisal of microbial interactions, which in turn help shape leaf microbiomes [5]. If so, this is an exciting prospect because it could offer targets for manipulation by plant breeders.

Data availability

Supplementary methods, figures and tables are provided in the files Supplementary Information and Supplementary Tables 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 11. Scripts and data used to recreate all figures and supplementary tables are publicly available via Figshare: https://figshare.com/projects/Niche_separation_in_cross-feeding_sustains_bacterial_strain_diversity_across_nutrient_environments_and_may_increase_chances_for_survival_in_nutrient-limited_leaf_apoplasts/125920. Raw sequencing data has been made publicly available in the NCBI BioProject PRJNA778092 and raw metabolomic data is being made publicly available in MetaboLights under the study MTBLS3719.

References

Chen T, Nomura K, Wang X, Sohrabi R, Xu J, Yao L, et al. A plant genetic network for preventing dysbiosis in the phyllosphere. Nature.2020;580:653–7.

Chaparro JM, Badri DV, Vivanco JM. Rhizosphere microbiome assemblage is affected by plant development. ISME J. 2014;8:790–803.

Manching HC, Carlson K, Kosowsky S, Smitherman CT, Stapleton AE. Maize phyllosphere microbial community niche development across stages of host leaf growth. F1000Research. 2017;6:1698.

Wagner MR, Lundberg DS, Del Rio TG, Tringe SG, Dangl JL, Mitchell-Olds T. Host genotype and age shape the leaf and root microbiomes of a wild perennial plant. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12151.

Agler MT, Ruhe J, Kroll S, Morhenn C, Kim ST, Weigel D, et al. Microbial hub taxa link host and abiotic factors to plant microbiome variation. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002352.

Durán P, Thiergart T, Garrido-Oter R, Agler M, Kemen E, Schulze-Lefert P, et al. Microbial interkingdom interactions in roots promote Arabidopsis survival. Cell. 2018;175:973–83. e14

Carrión VJ, Perez-Jaramillo J, Cordovez V, Tracanna V, de Hollander M, Ruiz-Buck D, et al. Pathogen-induced activation of disease-suppressive functions in the endophytic root microbiome. Science. 2019;366:606–12.

Karasov TL, Almario J, Friedemann C, Ding W, Giolai M, Heavens D, et al. Arabidopsis thaliana and Pseudomonas pathogens exhibit stable associations over evolutionary timescales. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:168–79.

Coleman-Derr D, Desgarennes D, Fonseca-Garcia C, Gross S, Clingenpeel S, Woyke T, et al. Plant compartment and biogeography affect microbiome composition in cultivated and native Agave species. N. Phytol. 2016;209:798–811.

Xiong C, Zhu YG, Wang JT, Singh B, Han LL, Shen JP, et al. Host selection shapes crop microbiome assembly and network complexity. N. Phytol. 2021;229:1091–104.

Lemonnier P, Gaillard C, Veillet F, Verbeke J, Lemoine R, Coutos-Thévenot P, et al. Expression of Arabidopsis sugar transport protein STP13 differentially affects glucose transport activity and basal resistance to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;85:473–84.

Nobori T, Cao Y, Entila F, Dahms E, Tsuda Y, Garrido-Oter R, et al. Dissecting the co-transcriptome landscape of plants and microbiota members. bioRxiv; 2022. p. 2021.04.25.440543.

Yamada K, Saijo Y, Nakagami H, Takano Y. Regulation of sugar transporter activity for antibacterial defense in Arabidopsis. Science. 2016;354:1427–30.

Baker RF, Leach KA, Braun DM. SWEET as sugar: new sucrose effluxers in plants. Mol Plant. 2012;5:766–8.

Tegeder M, Hammes UZ. The way out and in: phloem loading and unloading of amino acids. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2018;43:16–21.

O’Leary BM, Neale HC, Geilfus CM, Jackson RW, Arnold DL, Preston GM. Early changes in apoplast composition associated with defence and disease in interactions between Phaseolus vulgaris and the halo blight pathogen Pseudomonas syringae Pv. phaseolicola. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39:2172–84.

Rico A, Preston GM. Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 uses constitutive and apoplast-induced nutrient assimilation pathways to catabolize nutrients that are abundant in the tomato apoplast. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. MPMI. 2008;21:269–82.

Yu X, Lund SP, Scott RA, Greenwald JW, Records AH, Nettleton D, et al. Transcriptional responses of Pseudomonas syringae to growth in epiphytic versus apoplastic leaf sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E425.

Lohaus G, Winter H, Riens B, Heldt HW. Further studies of the phloem loading process in leaves of barley and spinach. The comparison of metabolite concentrations in the apoplastic compartment with those in the cytosolic compartment and in the sieve tubes. Bot Acta. 1995;108:270–5.

Chen LQ, Hou BH, Lalonde S, Takanaga H, Hartung ML, Qu XQ, et al. Sugar transporters for intercellular exchange and nutrition of pathogens. Nature. 2010;468:527–32.

Xin XF, Nomura K, Aung K, Velásquez AC, Yao J, Boutrot F, et al. Bacteria establish an aqueous living space in plants crucial for virulence. Nature. 2016;539:524–9.

Paulsen IT, Press CM, Ravel J, Kobayashi DY, Myers GSA, Mavrodi DV, et al. Complete genome sequence of the plant commensal Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:873–8.

D’Souza G, Shitut S, Preussger D, Yousif G, Waschina S, Kost C. Ecology and evolution of metabolic cross-feeding interactions in bacteria. Nat Prod Rep. 2018;35:455–88.

Hoek TA, Axelrod K, Biancalani T, Yurtsev EA, Liu J, Gore J. Resource availability modulates the cooperative and competitive nature of a microbial cross-feeding mutualism. PLOS Biol. 2016;14:e1002540.

Zimmermann J, Obeng N, Yang W, Pees B, Petersen C, Waschina S, et al. The functional repertoire contained within the native microbiota of the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. ISME J. 2020;14:26–38.

Machado D, Maistrenko OM, Andrejev S, Kim Y, Bork P, Patil KR, et al. Polarization of microbial communities between competitive and cooperative metabolism. Nat Ecol Evol. 2021;5:195–203.

Hassani MA, Durán P, Hacquard S. Microbial interactions within the plant holobiont. Microbiome. 2018;6:1–17.

Gerlich SC, Walker BJ, Krueger S, Kopriva S. Sulfate metabolism in C4 Flaveria species is controlled by the root and connected to serine biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2018;178:565–82.

Gowik U, Bräutigam A, Weber KL, Weber APM, Westhoff P. Evolution of C4 photosynthesis in the genus Flaveria: How many and which genes does it take to make C4? Plant Cell. 2011;23:2087–105.

McKown AD, Dengler NG. Vein patterning and evolution in C4 plants. Botany. 2010;88:775–86.

Gentzel I, Giese L, Zhao W, Alonso AP, Mackey D. A simple method for measuring apoplast hydration and collecting apoplast contents. Plant Physiol. 2019;179:1265–72.

Mayer T, Mari A, Almario J, Murillo-Roos M, Syed M, Abdullah H, et al. Obtaining deeper insights into microbiome diversity using a simple method to block host and nontargets in amplicon sequencing. Mol Ecol Resour. 2021;21:1952–65.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

Callahan B, McMurdie PJ, Rosen M, Han A, Johnson A, Holmes S. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–3.

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:61217.

Oksanen J, Blanchet GF, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Arkin AP, Cottingham RW, Henry CS, Harris NL, Stevens RL, Maslov S, et al. KBase: The United States Department of Energy Systems Biology Knowledgebase. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:566–9.

Schlechter RO, Jun H, Bernach M, Oso S, Boyd E, Muñoz-Lintz DA, et al. Chromatic bacteria – A broad host-range plasmid and chromosomal insertion toolbox for fluorescent protein expression in bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:3052.

Lohaus G, Pennewiss K, Sattelmacher B, Hussmann M, Hermann Muehling K. Is the infiltration-centrifugation technique appropriate for the isolation of apoplastic fluid? A critical evaluation with different plant species. Physiol Plant. 2001;111:457–65.

Trivedi P, Leach JE, Tringe SG, Sa T, Singh BK. Plant–microbiome interactions: from community assembly to plant health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:607–21.

Goldford JE, Lu N, Bajić D, Estrela S, Tikhonov M, Sanchez-Gorostiaga A, et al. Emergent simplicity in microbial community assembly. Science. 2018;361:469–74.

Dal Bello M, Lee H, Goyal A, Gore J. Resource-diversity relationships in bacterial communities reflect the network structure of microbial metabolism. Nat Ecol Evol. 2021;5:1424–34.

Sattelmacher B. The apoplast and its significance for plant mineral nutrition. N. Phytol. 2001;149:167–92.

Regalado J, Lundberg DS, Deusch O, Kersten S, Karasov T, Poersch K, et al. Combining whole-genome shotgun sequencing and rRNA gene amplicon analyses to improve detection of microbe–microbe interaction networks in plant leaves. ISME J. 2020;14:2116–30.

Morella NM, Weng FCH, Joubert PM, Metcalf CJE, Lindow S, Koskella B. Successive passaging of a plant-associated microbiome reveals robust habitat and host genotype-dependent selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:1148–59.

Remus-Emsermann MNP, Lücker S, Müller DB, Potthoff E, Daims H, Vorholt JA. Spatial distribution analyses of natural phyllosphere-colonizing bacteria on Arabidopsis thaliana revealed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:2329–40.

Coyte KZ, Schluter J, Foster KR. The ecology of the microbiome: Networks, competition, and stability. Science. 2015;350:663–6.

Herren CM. Disruption of cross-feeding interactions by invading taxa can cause invasional meltdown in microbial communities. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2020;287:20192945.

Rahme LG, Mindrinos MN, Panopoulos NJ. Plant and environmental sensory signals control the expression of hrp genes in Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3499–507.

Morella NM, Zhang X, Koskella B. Tomato seed-associated bacteria confer protection of seedlings against foliar disease caused by Pseudomonas syringae. Phytobiomes J. 2019;3:177–90.

Cha JY, Han S, Hong HJ, Cho H, Kim D, Kwon Y, et al. Microbial and biochemical basis of a Fusarium wilt-suppressive soil. ISME J. 2016;10:119–29.

Lundberg DS, Jové R de P, Ayutthaya PPN, Karasov TL, Shalev O, Poersch K, et al. Contrasting patterns of microbial dominance in the Arabidopsis thaliana phyllosphere. bioRxiv. 2021;2021.04.06.438366.

Ikawa Y, Tsuge S. The quantitative regulation of the hrp regulator HrpX is involved in sugar-source-dependent hrp gene expression in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363:fnw071.

Wei ZM, Sneath BJ, Beer SV. Expression of Erwinia amylovora hrp genes in response to environmental stimuli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1875–82.

Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5114.

Akashi H, Gojobori T. Metabolic efficiency and amino acid composition in the proteomes of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3695–700.

Oña L, Kost C. Cooperation increases robustness to ecological disturbance in microbial cross-feeding networks. Ecol Lett. 2022;25:1410–20.

Cadot S, Guan H, Bigalke M, Walser JC, Jander G, Erb M, et al. Specific and conserved patterns of microbiota-structuring by maize benzoxazinoids in the field. Microbiome. 2021;9:103.

Voges MJEEE, Bai Y, Schulze-Lefert P, Sattely ES. Plant-derived coumarins shape the composition of an Arabidopsis synthetic root microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:12558–65.

Aulakh MS, Wassmann R, Bueno C, Kreuzwieser J, Rennenberg H. Characterization of root exudates at different growth stages of ten rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. Plant Biol. 2001;3:139–48.

Dietz S, Herz K, Gorzolka K, Jandt U, Bruelheide H, Scheel D. Root exudate composition of grass and forb species in natural grasslands. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10691.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Carl-Eric Wegner, Stefan Riedel and Professor Kirsten Küsel for making their sequencing equipment and knowledge available to us. We gratefully acknowledge the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft CRC 1127 “ChemBioSys” who funded the UHPLC-HRMS system used for metabolomics experiments.

Funding

MTA is supported by the Carl Zeiss Stiftung via the Jena School for Microbial Communication and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2051 – Project-ID 390713860. MMR is supported by the International Leibniz Research School. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMR and MTA conceived of and initiated the project. HSMA performed enrichments from plant material and isolation and characterization of enriched bacteria. MD performed plant colonization assays. All other experiments were conducted by MMR and NU carried out metabolomics runs. MMR analyzed the data with help from HSMA and MD. MMR and MTA wrote the manuscript, with contributions and approval from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murillo-Roos, M., Abdullah, H.S.M., Debbar, M. et al. Cross-feeding niches among commensal leaf bacteria are shaped by the interaction of strain-level diversity and resource availability. ISME J 16, 2280–2289 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-022-01271-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-022-01271-2

This article is cited by

-

Metabolic resource overlap impacts competition among phyllosphere bacteria

The ISME Journal (2023)