Abstract

Introduction

Primary epidural Ewing’s sarcoma in the lumbar spinal canal is a rare condition and very few cases are reported in the literature.

Case report

A fifteen-year-old girl presented with low backache associated with sudden onset of weakness and radiculopathy of both lower limbs for 10 days, bowel and bladder involvement for 3 days. Physical examination revealed grade 0/5 power and absent sensations below L4 dermatomal level and perianal region (ASIA A). Plantar reflex was mute bilaterally. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed an extradural lesion within the spinal canal at the L3–L4 level. The patient underwent an emergency posterior decompression, extradural lesion excision and instrumented stabilization L3–L5. Based on histopathological examination of the tissue specimen, we diagnosed the lesion as Ewing sarcoma.

Discussion

Primary extra-skeletal Ewing’s sarcoma presenting as an epidural lesion in the lumbar spine is a rare clinical entity that should be considered as a differential for spinal epidural lesions. Treatment for such cases is almost always an early surgical intervention due to its rapid onset and compressive neurological symptoms. Wide decompression with instrumented fusion and excision of the lesion followed by chemo and radiotherapy are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

First described by James Ewing in 1921 [1], Ewing’s sarcoma of bone is the most common malignant bone tumor in the first decade of life and the second after osteosarcoma in the second decade of life [2]. Ewing sarcoma is now considered to be part of a larger group of malignancies called the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors that includes Ewing sarcoma, extraosseous Ewing sarcoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, and Askin tumor [3].

Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma was first described by Tefft et al. in 1969 [4]. It can arise in various locations like the chest wall, paravertebral muscles, extremities, pelvis, and retroperitoneal space [5].

Primary Ewing sarcoma in the lumbar epidural space causing cord or neural compression is a rare condition and very few cases are reported in the literature. Rapidly progressing paraplegia with bladder & bowel incontinence can be the presenting symptoms in a young patient which creates a diagnostic dilemma. A high index of suspicion is required to diagnose lumbar epidural Ewing’s sarcoma. This case report highlights such a rare presentation of the disease and successful recovery of the patient with proper surgical management.

Case report

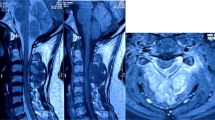

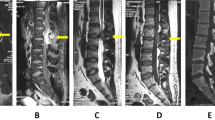

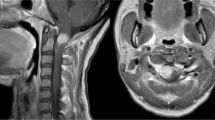

A 15-year-old bedridden girl with grade II gluteal bedsore presented with low backache associated with sudden onset of weakness and radiculopathy of both lower limbs for 10 days, bowel and bladder involvement for 3 days. Physical examination revealed a grade of 0/5 power in both lower limbs with no sensations below L4 level and also absent perianal sensation (ASIA A). Plantar reflex was mute bilaterally. Laboratory examinations were not significant. Radiographs of the spine revealed no abnormal bony destruction. Magnetic Resonance Imaging revealed a lesion within the spinal canal at L3–4 level measuring 1.3 × 1.2 × 5.3 cm, slightly towards the left of the midline. The lesion was hypointense on T1 and isointense on T2 with T2 hypointense focus in its superior aspect. The lesion was seen to be abutting the L3–4 neural foramen on the left. The filum terminale and cauda equina nerve roots were not seen separately at this level while they were displaced anteriorly (Figs. 1, 2).

Because of rapidly progressing paraplegia with bladder & bowel incontinence, urgent posterior spinal decompression L3–L4 and excision of the lesion was contemplated. Intra-operatively, an intra-spinal soft tissue lesion was noted compressing the thecal sac extradurally which was excised and sent for histopathology. Instrumented fusion from L3 to L5 was done as the facet joints needed to be compromised for adequate decompression of neural structures. Histopathological examination of the specimen showed atypical cells composed of small, round cells having a high nucleus to cytoplasmic ratio with moderate nuclear pleomorphism (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemistry was done for confirmation and subtyping, which were positive for CD99 (Fig. 4A), FLI-1 (Fig. 4B), NKX 2.2 (Fig. 4C), CK but negative for Desmin, Synaptophysin, CD45, SMA, LCA, S-100. MIB-1 labeling index was 80–85%. Based on these immunohistochemistry reports, a diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma was made. Post-operatively, the patient had sensory recovery in both lower limbs on the first postoperative day. Motor examination revealed an improvement in motor power by 1 grade in L4 & L5 myotomes. She was then planned for an adjuvant chemotherapy regimen which consisted of a combination of vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide and ifosfamide (VAC- IE regimen). Radiation therapy was initiated in the surgical site and continued in fractionated doses to a total of 45 Gy. At 2 years follow up, the patient had significant neurological recovery and was walking with support. Power was grade 3 in both lower limbs. Radiologically, there was no evidence of recurrence or metastasis.

Discussion

Ewing’s sarcoma is a small round cell tumor originating in bones and rarely, in soft tissues of young children [6]. Ewing’s family of tumors includes Ewing’s tumor of Bone, extraosseous Ewing tumors, primitive neuro-ectodermal tumors (PNET)/peripheral neuro-epithelioma, and Askin tumors (PNET of the chest wall). These are regarded as a single entity because of the common occurrence of pathognomonic translocation of chromosomes 22 & 11 [7,8,9].

Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma arising in the epidural space is a rare entity and very few cases are reported in the literature. The review of the literature on combined pediatric and adult spinal epidural Ewing sarcomas showed that the lumbar region is the most common site, followed by the thoracic and cervical spine, with the sacral region being the least common (5% of cases) [10, 11]. Bustoros et al, in their review of literature on adult epidural Ewing Sarcomas, found that the most common site was the thoracic spine followed by lumbar, cervical, and sacral segments [12].

Our literature review yielded 20 cases of primary Ewing sarcoma arising in the lumbar epidural space from 1969 to 2021 (summarized in Table 1). The occurrence was more common in males (55%) and the mean age at presentation was 15.26 years. All the patients presented with low back pain and 90% of the cases had acute onset of neurological deficits with or without bowel and bladder involvement at the time of presentation. The most common differential diagnosis on clinical examination may be intervertebral disc herniation [13, 14].

To accurately diagnose extraskeletal epidural Ewing sarcoma, it is important to rule out several other potential etiologies of an epidural mass. It includes tumors that histologically resemble an extraosseous Ewing sarcoma like lymphoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, and neuroblastoma [15]. MRI is the imaging modality of choice to diagnose such lesions. It also helps in the determination of the anatomic relationships with surrounding structures, and preoperative surgical planning [12]. The tumor is usually hypo-isointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2- weighted images and enhance homogenously or heterogeneously [16].

Although clinical and radiological findings are essential in the early diagnosis of primary epidural Ewing sarcoma, a definitive diagnosis can be made only based on histopathologic examination which includes immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis [16]. The classical histopathologic findings are sheets, lobules, and occasional rosettes of round cells with irregular nuclei and sparse cytoplasm [17].

At the molecular level, Ewings sarcoma is caused by a gene fusion involving a member of the FET family (usually EWSR1) and a member of the ETS family of transcription factors [18]. The t(11;22)(q24;q12) translocation, which is seen in >85% of cases, results in the formation of a chimeric gene (EWSR1- FLI1) and has been found to act as an oncogenic transcription factor in Ewings sarcoma and peripheral neuroectodermal tumors [19], another translocation t(21; 22)(q22; q12), resulting in EWSR1-ERG fusion, is also seen in ~10% of cases. 50 Other translocations can also occur, involving other ETS genes (FEV, ETV1, E1AF) [20]. These translocations can be detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) in the nuclei of neoplastic cells or by RT-PCR. According to the latest guidelines, the European society of medical oncology (ESMO) recommends molecular confirmation as mandatory for the distinction between Ewings sarcoma and other Round cell sarcomas. Assays that use EWSR1 break-apart probes detect only EWSR1 rearrangements and not their fusion partner and can be interpreted easily with an appropriate clinical and pathological background [21].

When deciding about the treatment of Ewing’s sarcoma of the spine, the most important determinant may be regarded as the presence of neurological deficits, which once present are often rapidly progressive. In such circumstances, only a prompt surgical decompression can provide a maximum chance of recovery [22]. Most of the cases of Ewing sarcoma of the epidural space are treated by marginal or intralesional resection to preserve the dura and the nerves and as an emergency procedure given rapid neurological deterioration even before a definitive pathological diagnosis is made. Therefore, resection with an insufficient tumor resection margin in Ewing sarcoma that is pathologically diagnosed after the surgery results in poor outcomes including high recurrence and low survival rate [23].

Postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy for control of micrometastases are warranted. Currently, the chemotherapy guidelines for the treatment of the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors consider VAC/IE regimen (vincristine, actinomycin, cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide or etoposide) as the preferred first-line drugs for localized disease, concurrently with radiotherapy (45 Gy in 25 fractions) [24]. The addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to the induction and maintenance phase of chemotherapy was found to improve the outcome in terms of histological response and overall survival of the patient [25]. Neoadjuvant therapy may be of limited use in spinal epidural EES, due to the need for emergency surgical decompression of the spinal cord.

Though controversial, the location may be one of the prognostic factors of the Ewing sarcoma [26]. In the review of literature by Chiang et al., cases with primary epidural Ewing sarcomas occurring in the lumbosacral spine had a lower survival rate and highly metastatic tendency compared to cases with cervicothoracic localization [27]. A possible explanation for the difference in prognosis may be due to the larger epidural space in the lower third of the spine which delays the presentation of symptoms and the diagnosis [27]. In our literature review of 19 cases of lumbar epidural Ewing sarcoma, 7 out of 20 patients (36.8%) died within 12 months of diagnosis and treatment due to metastasis to various vital organs while 11 cases had complete neurological recovery at follow up. There was no documentation regarding follow up or survival of the remaining 2 cases.

Because of the urgent nature of the presentation, a rare case of epidural Ewing’s sarcoma came to be diagnosed, with MRI playing a pivotal role in characterizing the lesion and surgical planning, followed by adequate decompression, excision of the lesion and instrumented fusion. After that, the patient was sent for a VAC-IE chemotherapy regimen. Therefore, for early diagnosis and treatment of epidural Ewing’s sarcoma of the lumbar spine, a high index of suspicion is required. Early presentation with neurological deficits or rapid deterioration might have a chance of earlier diagnosis due to the urgency of the situation, but for the patients who present with more benign symptoms, such cases might be misinterpreted as disc disease, or a more benign pathology, which might delay the diagnosis, and hence the further management.

Conclusion

Epidural Ewing’s sarcoma of the lumbar region is an important differential diagnosis to consider in cases with sudden onset neurological deficits in lower limbs or cauda equina syndrome with no significant past history or constitutional symptoms, especially in young patients. A multi-specialty approach is paramount in such cases, including radiological expertize in the identification of such lesions, and urgent surgical management in the form of decompression and tumor excision, followed by histopathological correlation. Co-management with an oncological team in form of chemo and radiotherapy is essential for adequate treatment.

References

Ewing J. Diffuse Endothelioma of Bone. Proc. New York Path. Soc. 1921;21:17–24.

Esiashvili N, Goodman M, Marcus RB. Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J Pediatr Hematol/Oncol. 2008;30:425–30.

Ries L, Percy C, Bunin G. Introduction—SEER pediatric monograph. Cancer Incid survival Child adolescents: US SEER Program. 1975;1995:1–15.

Tefft M, Vawter G, Mitus A. Paravertebral “round cell” tumors in children. Radiology. 1969;92:1501–9.

Raney RB, Asmar L, Newton WA, Bagwell C, Breneman JC, Crist W, et al. Ewing’s sarcoma of soft tissues in childhood: a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study, 1972 to 1991. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:574–82.

Tsokos M, Alaggio RD, Dehner LP, Dickman PS. Ewing sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor and related tumors. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2012;15:108–26.

Angervall L, Enzinger F. Extraskeletal neoplasm resembling Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;36:240–51.

Askin FB, Rosai J, Sibley RK, Dehner LP, McAlister WH. Malignant small cell tumor of the thoracopulmonary region in childhood. A distinctive clinicopathologic entity of uncertain histogenesis. Cancer. 1979;43:2438–51.

Jaffe R, Santamaria M, Yunis E, Tannery NH, Agostini R Jr, Medina J, et al. The neuroectodermal tumor of bone. Am J Surgical Pathol. 1984;8:885–98.

Kazanci A, Gurcan O, Gurcay AG, Senturk S, Yildirim AE, Kilicaslan A, et al. Primary ewing sarcoma in spinal epidural space: report of three cases and review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2015;32:250–61.

Saeedinia S, Nouri M, Alimohammadi M, Moradi H, Amirjamshidi A. Primary spinal extradural Ewing’s sarcoma (primitive neuroectodermal tumor): Report of a case and meta-analysis of the reported cases in the literature. Surg Neuro Int. 2012;3:55.

Bustoros M, Thomas C, Frenster J, Modrek AS, Bayin NS, Snuderl M, et al. Adult primary spinal epidural extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Case reports in neurological medicine. 2016;2016:1217428.

Fink LH, Meriwether MW. Primary epidural Ewing’s sarcoma presenting as a lumbar disc protrusion: Case report. J Neurosurg. 1979;51:120–3.

Ruelle A, Boccardo M. Epidural extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma simulating a herniated disk. Clinical case. Riv di Neurologia. 1986;56:183–8.

Shin JH, Lee HK, Rhim SC, Cho K-J, Choi CG, Suh DC. Spinal epidural extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma: MR findings in two cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:795–8.

Ozturk E, Mutlu H, Sonmez G, Aker FV, Basekim CC, Kizilkaya E. Spinal epidural extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma. J Neuroradiol. 2007;34:63–7.

Kennedy JG, Eustace S, Caulfield R, Fennelly DJ, Hurson B, O’Rourke KS. Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Spine. 2000;25:1996–9.

Choi JH, Ro JY. The 2020 WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue: selected changes and new entities. Adv Anat Pathol. 2021;28:44–58.

Machado I, López-Guerrero JA, Llombart-Bosch A. Biomarkers in the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors. Curr Biomark Find. 2014;4:81.

Riggi N, Suvà ML, Stamenkovic I. Ewing’s sarcoma. N. Engl J Med. 2021;384:154–64.

Strauss SJ, Frezza AM, Abecassis N, Bajpai J, Bauer S, Biagini R, et al. Bone sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS-ERNPaedCan Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1520–36.

Pizzo PA, Poplack DG. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;2:203–4.

Kobayashi S, Takahashi J, Sakashita K, Fukushima M, Kato H. Ewing sarcoma of the thoracic epidural space in a young child. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:373–9.

Palumbo R, Palmeri S, Gatti C, Villani G, Cesca A, Toma S. Combination chemotherapy using vincristine, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide (VAC) alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide (IE) for advanced soft tissue sarcomas: a phase II study. Oncol Rep. 1998;5:69–141.

Ferrari S, Mercuri M, Rosito P, Mancini A, Barbieri E, Longhi A, et al. Ifosfamide and actinomycin-D, added in the induction phase to vincristine, cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin, improve histologic response and prognosis in patients with non metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma of the extremity. J Chemother. 1998;10:484–91.

Harimaya K, Oda Y, Matsuda S, Tanaka K, Chuman H, Iwamoto Y. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor and extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma arising primarily around the spinal column: report of four cases and a review of the literature. Spine. 2003;28:E408–12.

Hsieh C-T, Chiang Y-H, Tsai W-C, Sheu L-F, Liu M-Y. Primary spinal epidural Ewing sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Turkish J Paediatrics. 2008;50:282.

Mahoney JP, Ballinger WE Jr, Alexander RW. So-called extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma: report of a case with ultrastructural analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;70:926–31.

Scheithauer BW, Egbert BM. Ewing’s sarcoma of the spinal epidural space: report of two cases. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1978;41:1031–5.

Simonati A, Vio M, Iannucci A, Bricolo A, Rizzuto N. Lumbar epidural Ewing sarcoma. J Neurol. 1981;225:67–72.

Spaziante R, de Divitiis E, Giamundo A, Gambardella A, Di Prisco B. Ewing’s sarcoma arising primarily in the spinal epidural space: Fifth case report. Neurosurgery.1983;12:337–4.

Valtueña MM, Garcia-Sagredo J, Villa AM, Giménez CL, Meix JA. 18q-syndrome and extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma. J Med Genet. 1987;24:426–8.

Kaspers GJJ, Veerman AJ, Kamphorst W, van de Graaff M, van Alphen HAM. Primary spinal epidural extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer.1991;68:648–54.

Allam K, Sze G. MR of primary extraosseous Ewing sarcoma. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:305–7.

Mukhopadhyay P, Gairola M, Sharma M, Thulkar S, Julka P, Rath G. Primary spinal epidural extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma: report of five cases and literature review. Australas Radiol. 2001;45:372–9.

Kadri PADS, Mello PMPD, Olivera JGD, Braga FM. Primary lumbar epidural Ewing’s sarcoma: case report. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria. 2002;60:145–9.

Weber D, Rutz H, Lomax A, Schneider U, Lombriser N, Zenhausern R, et al. First spinal axis segment irradiation with spot-scanning proton beam delivered in the treatment of a lumbar primitive neuroectodermal tumour: Case report and review of the literature. Clin Oncol. 2004;16:326–31.

Ozdemir N, Usta G, Minoglu M, Erbay AM, Bezircioglu H, Tunakan M. Primary primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the lumbar extradural space: Case report. J Neurosurg Pediatrics. 2008;2:215–21.

Giner J, Isla A, Cubedo R, Tejerina E. Primary epidural lumbar ewing sarcoma: Case report and review of the literature. Spine. 2016;41:E375–8.

Addesso L, Koenig D, Huq N. Lower extremity weakness in an adolescent female–a rare presentation of ewing sarcoma. Ochsner J. 2018;18:402–5.

Fletcher AN, Marasigan JAM, Hiatt SV, Anderson JT, Taboada EM, Schwend RM. Primary spinal epidural/extramedullary ewing sarcoma in young female patients. JAAOS Glob Res Rev. 2019;3:e19.00072.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soni, A., Kareem, S.A., Ramachandraiah, M.K. et al. Primary extra-skeletal Ewing’s sarcoma presenting as an epidural Soft Tissue Lesion causing cauda equina syndrome in an adolescent girl: a case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 8, 13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-021-00474-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-021-00474-7