Abstract

Introduction

Subependymomas are slow growing WHO grade 1 tumours, typically attached to the ventricular wall of the fourth or lateral ventricles. Spinal subependymomas are rarer still and experience of their biological characteristics remains limited.

Case presentation

A 29-year-old lady presented with chronic attacks of itchy dysaesthesia involving the left hand, neck and trunk, and associated with ipsilateral leg spasms. Recent symptomatic change involved occasional limping and left sided facial numbness but no pain. MRI showed an intradural mass surrounding most of the cervical spinal cord, which appeared scalloped extrinsically, rather than diffusely expanded, by a seemingly extramedullary lesion. At operation, the cord appeared expanded, with no clear margin or distinction between tumour and cord tissue; and the tumour was found to be intramedullary with an exophytic component, rather than extramedullary. Moderate reduction of the left abductor pollicis brevis evoked potential led to a pause in surgery. There was transient hand weakness postoperatively with full recovery, and no radiological change in the tumour morphology for a further 6 years.

Discussion

An intramedullary tumour such as a spinal cord subependymoma can be mistaken radiologically for an extramedullary tumour, such as an epidermoid. If a subependymoma is suspected, given its indolent course and long-term survival, caution in the extent of surgical resection is advisable in order to avoid surgical morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Subependymomas are slow growing WHO grade 1 tumours, typically attached to a ventricular wall, and occur mostly in the fourth ventricle (50–60%), followed by the lateral ventricle (30–40%) [1]. They were first recognised in 1945 and the first spinal cord case was reported in 1954; the second case report of a spinal subependymoma was not until 25 years later [2, 3]. Experience of their biological characteristics remains limited owing to their rarity. Radiological diagnosis can be challenging, but a heterogenous intramedullary lesion with little or no enhancement and eccentric location with slow clinical progression of symptoms is suggestive.

Case presentation

Informed consent was obtained from the patient. A 29-year-old female presented with repeated attacks of itchy dysaesthesia spanning a period of 13 years. The sensation would start in the left hand, spreading up into the neck and trunk. The sensation would often last for over 10 min. When this occasionally lasted for over 30 min, she would then experience jumping spasms of the left leg. Infrequently, the symptoms would last for up to one day. Over the last 3 years her gait was starting to get affected, as the family noted an occasional limp. There was also a 3-month history of left sided facial numbness but no pain. This involved all three divisions of the trigeminal nerve territory but was not associated with any pain.

Clinical examination revealed a tardy left fine finger movement; weakness (4/5) in left elbow extension, fingers extension and abduction; left sided hyperreflexia with left ankle clonus; and dysaesthesia of the left foot. Cranial nerve examination was normal and in particular revealed no objective loss of sensation (to pain, touch and temperature) in the trigeminal distribution. Corneal reflex and sensation were intact.

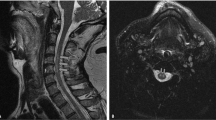

Radiology: MRI of the brain, including the pons and Meckel’s cave, was normal. MRI of the spine showed an intradural mass surrounding the cord from C2 to C7. The cervical cord appeared scalloped extrinsically, rather than diffusely expanded, by an extramedullary process seen to be insinuating around the left side of the cord. The lesion was T1 isointense to hypointense and T2 hyperintense, with no contrast enhancement. It appeared extramedullary and there was a normal signal in the immediately adjacent cord. The appearances were suggestive of an epidermoid tumour (see Fig. 1). The radiological findings were consistent with the symptoms. The subjective sensory loss in the trigeminal territory was believed to be trigeminal sensory neuropathy due to potential involvement of the spinal trigeminal tract [4, 5].

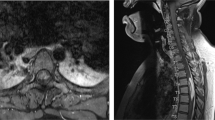

Surgery: Via a C2/3 to C7/T1 laminoplasty, the spinal cord appeared expanded with no clear margin or distinction between tumour and spinal cord tissue (see Fig. 2). The tumour was debulked in the left-sided intradural gutter and in between the nerve roots at C3 and C4 levels. There was no obvious demarcation between tumour and cord, and intraoperatively the tumour felt to be intramedullary with an exophytic component, rather than extramedullary. There was initial SSEP improvement from baseline with debulking; however, a moderate reduction in the evoked potential of the left abductor pollicis brevis led to a pause in surgery. Samples were sent for frozen section histopathology; there was no evidence of an epidermoid cyst as suspected radiologically, but instead a sparsely cellular glioma with tumour cells embedded in a dense glial matrix. Further debulking was aborted in view of the pathology results suggestive of an intrinsic glioma, a fluctuation in the SSEPs and MEPs and the lack of any distinctive plane between the tumour and surrounding spinal cord tissue. Final histology confirmed typical features of a subependymoma (see Figs. 3A, B, C).

No mitotic figures were identified and necrosis was absent. No ependymal canaliculi or pseudorosettes were observed and microcytic degeneration was absent. The glial matrix around the tumour cells stained intensely with an antibody to glial fibrillary acidic protein (Fig. 3B). Antibodies to epithelial membrane antigen and isocitrate dehydrogenase gave no staining, but the MIB-1 antibodies revealed a low rate of cellular proliferation (Fig. 3C). (A)Small uniform tumour cell nuclei occur in scattered groups within a glial matrix. Haematoxylin and eosin stain, X 100. (B)The glial matrix stains intensely with the antibody to glial fibrillary acidic protein (brown). Haematoxylin counterstain, x 100. (c)The MIB-1 antibody reveals a low rate of cellular proliferation within the tumour (proliferating nuclei are labelled brown). Haematoxylin counterstain, x 200.

Following surgery, the patient experienced worsening neuropathic pain with mild weakness in her left hand. However, by 7 months after surgery her left-hand grip had returned to normal power, and the pain sensation had improved. At the latest follow up 7 years post operation, she has normal power although she still gets occasional burning dysaesthesia. Radiological surveillance over this period has shown no change in the residual tumour.

Discussion

The incidence of spinal tumours is difficult to quantify and is usually presented from case series rather than epidemiological studies. The incidence of rarer tumours- like a spinal subependymoma- is even more difficult to report and is estimated at approximately 1% of all intramedullary tumours, and 15% of all CNS subependymomas. In a fairly recent systematic review of the literature, we synthesised evidence from a little over 100 cases reported, with close to half of these being reported in the last 5 years. The length of time with symptoms at presentation can vary from a month to 17 years, and sensory symptoms- like in our case- seem to be the most frequent at 80% [1].

Not all radiologically reported “extramedullary” cases are truly that. A spinal cord subependymoma can be mistaken preoperatively for an extramedullary tumour, such as an epidermoid.

Our case had global improvement with debulking, but reduction in the abductor pollicis brevis evoked potentials of the non-dominant hand; and initial hand weakness, which improved on post-operative follow up.

Some reported cases recommend complete resection for a cure. An important lesson of the reviewed cases was that a reporting rate of 75% total resection came at the expense of 53% worsening of postoperative function. Importantly, the literature suggests that long-term survival is expected, while there were no reports of malignant transformation [1, 6]. Therefore, where there is minimal symptom progression surgical caution should be exercised.

The pause during surgery due to a slight reduction in evoked potentials was wise and lends further support to the use of intraoperative neuromonitoring is a major intraoperative adjunct in the modern treatment of spinal cord tumours [7,8,9,10].

Conclusion

Our case demonstrates that an intramedullary tumour such as a spinal cord subependymoma can be mistaken radiologically for an extramedullary tumour, such as an epidermoid. If a subependymoma is suspected, given its indolent course and long-term survival, caution in the extent of surgical resection is advisable in order to avoid surgical morbidity.

Change history

17 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-021-00469-4

References

Soleiman HA, Ironside J, Kealey S, Demetriades AK. Spinal subependymoma surgery: do no harm. Little may be more! Neurosurg Rev 2020;43:1047–53. Epub 2019 Jun 18. PMID: 31214945

Scheiker JM. Subependymoma: Newly recognized tumour of subependymal derivation. J Neurosurg. 1945;49:232–40.

Boykin FC, Cowen D, Iannucci CA, Wolf A. Subependymal glomerate astrocytomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1954;13:30–49. PMID: 13118373

Barakos JA, D’Amour PG, Dillon WP, Newton TH. Trigeminal sensory neuropathy caused by cervical disk herniation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1990;11:609. PMID: 2112329

Sellin JN, Al-Hafez B, Duckworth EA. Microvascular decompression of a C-2 segmental-type vertebral artery producing trigeminal hypesthesia. J Neurosurg 2014;121:919–23. Epub 2014 Jun 27. PMID: 24972125

Wu L, Yang T, Deng X, Yang C, Zhao L, Fang J, et al. Surgical outcomes in spinal cord subependymomas: an institutional experience. J Neurooncol 2014;116:99–106. Epub 2013 Sep 24. PMID: 24062139

Westphal M, Mende KC, Eicker SO. Refining the treatment of spinal cord lesions: experience from 500 cases. Neurosurg Focus. 2021;50(May):E22. PMID: 33932931

Scibilia A, Terranova C, Rizzo V, Raffa G, Morelli A, Esposito F, et al. Intraoperative neurophysiological mapping and monitoring in spinal tumor surgery: sirens or indispensable tools? Neurosurg Focus. 2016;41(Aug):E18. PMID: 27476842

Ghadirpour R, Nasi D, Iaccarino C, Romano A, Motti L, Sabadini R, et al. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring for intradural extramedullary spinal tumors: predictive value and relevance of D-wave amplitude on surgical outcome during a 10-year experience. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;30(Nov):259–67. PMID: 30497134

Ghadirpour R, Nasi D, Iaccarino C, Giraldi D, Sabadini R, Motti L, et al. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring for intradural extramedullary tumors: why not? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2015;130:140–9. Epub 2015 Jan 12. PMID: 25618840

Acknowledgements

The input of Professor James Ironside, Consultant Neuropathologist, is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were responsible for the planning, conduct, and reporting of the work described in the article; AKD is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Demetriades, A.K., Soleiman, H.A. & Kealey, S. A case of chronic dysaesthesia in the torso and upper limbs: lessons from a cervical spinal cord subependymoma. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 7, 52 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-021-00416-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-021-00416-3