Abstract

Introduction

Brown-Séquard Syndrome (BSS) is one of the rarest incomplete spinal cord syndromes. The combination of injuries to peripheral nerves and the central nervous system result in an array of symptoms that can result in overlapping clinical presentations and delayed diagnosis. Early detection of spinal cord injury in patients with peripheral nerve injury has been observed to have a positive effect on outcomes.

Case presentation

This report discusses the case of a 29-year-old male patient with Brown-Sequard-Plus Syndrome (BSPS) and Brachial Plexopathy (BP) secondary to gunshot wound in the left inferior neck. The patient was found initially with left hemibody weakness. A chest CT Scan demonstrated a fracture of the left T2 transverse process. Imaging studies of the spinal cord were not performed in the acute setting. Evaluation in an outpatient setting 3 weeks later showed significant left upper extremity weakness with improvement of left lower extremity strength. Also present were loss of pain and temperature sensation on the right side below the T2 dermatome level. A cervico-thoracic MRI was requested and revealed a T2 level spinal cord contusion. Electrodiagnostic studies confirmed a lower trunk left BP.

Discussion

The patient was diagnosed with BSPS and associated left lower trunk BP. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a concomitant BSPS and BP secondary to a gunshot wound. Delayed diagnosis of BSPS may occur in a trauma setting underlying the importance of a detailed history and physical examination for favorable outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injuries (SCI) have a reported global annual incidence between 250,000–500,000 cases [1]. Spinal cord syndromes are organized based on their anatomical site of injury and subsequent clinical presentation. One of these syndromes is Brown-Séquard Syndrome (BSS) which accounts for 1–4% of all the SCI, making it one of the rarest [2, 3]. BSS is defined as damage to a hemisection of the spinal cord causing a characteristic pattern of symptoms consisting of 1) ipsilateral weakness (disruption of the corticospinal tract); 2) ipsilateral loss of fine touch, proprioception, and vibratory sensation (disruption of the dorsal columns); and 3) loss of pain, temperature, and crude touch on the contralateral side (disruption to the spinothalamic tract) [3]. However, it has also been described as Brown Séquard Plus Syndrome (BSPS) when the injury is incomplete and presents with loss of bladder, bowel, or eye control [4, 5].

BSPS is usually associated with other comorbidities, especially when the cause is trauma or gunshot wounds (GSWs). Specifically, GSW may present unique characteristics that depend on the entry and exit path of the projectile. The effect of its blast circumference may create a shockwave and damage adjacent structures. Cases of BSPS secondary to GSW have been reported [3, 6]. However, to our knowledge, this is the first case of a BSPS accompanied by a BP after GSW. The combination of peripheral nerve and central nerve injuries displays an array of symptoms that can possibly cause one pathology to mask the other [7]. This unusual overlap pattern of symptoms may cause a delay in the diagnosis of either injury. It is of therapeutic value to identify the coexistence of these lesions since early detection of SCI in patients with brachial plexus injury has been observed to have a positive effect on surgical and rehabilitation outcomes [8].

Therefore, due to the limited evidence available of the coexistence of BSPS and BP after a GSW and the high degree of therapeutic value that can come from successful clinical identification of this rare co-occurrence, this case report aims to provide understanding about the clinical presentation of concomitant BSPS and BP secondary to GSW.

Case presentation

A 29-year-old male patient with no past medical history suffered a GSW while driving. The reported GSW involved one single projectile with entry in the left antero-inferior neck region. The patient was taken to the Trauma Center Emergency Department with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 15/15 but later required mechanical ventilation secondary to respiratory distress. A CT of the neck and chest confirmed a small left lung anterior and apical pneumothorax with associated alveolar hemorrhage. A severely comminuted fracture of the left 1st rib posterior aspect and of the T2 left transverse process was also reported. A penetrating injury was identified with evidence of soft tissue swelling and subcutaneous emphysema tracking from the left anterior neck supraclavicular region (C6/C7 vertebral body level) into the left neck visceral space, carotid space, lung apex, and left posterior upper back. (Table 1) The patient was extubated 8 days after the event.

Ten days later, the patient was seen by the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) consultant for evaluation and further management. On evaluation the patient presented with left hemibody weakness more prominent in the distal upper limb (Table 2). Because the patient had evidence of lower motor signs with a negative head CT scan, the upper limb weakness was attributed to a probable peripheral nerve etiology secondary to GSW. Physical therapy and further evaluation at the PM&R outpatient clinic for an electrodiagnostic study was recommended.

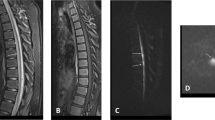

Three weeks after the GSW the patient showed significant left distal upper limb weakness with associated improvement of left lower limb strength. (Table 2) Physical examination revealed loss of pain and temperature sensation below the right T2 dermatome level with intact proprioceptive and vibratory sensation. Since the patient was not initially evaluated for spinal cord injury and presented with history of bladder incontinence and bowel constipation, a cervico-thoracic MRI was requested. Imaging revealed T2 level spinal cord edema compatible with a spinal cord contusion (Fig. 1). The diagnosis of an incomplete spinal cord injury ASIA D T2 Level consistent with BSPS was made. An electrodiagnostic study two months after the accident confirmed a left BP primarily affecting the lower trunk (Table 3). A timetable summarizing the evolution of the patient’s clinical condition is presented in Table 1.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first documented case of BSPS associated with a BP secondary to GSW. There are reports of combined Brown–Sequard Syndrome with BP but most are preganglionic lesions secondary to root avulsion and thus represent radiculopathies and not BPs [8,9,10]. This case demonstrates the difficulty of the acute evaluation of patients with trauma.

The presence of the two diagnoses were confirmed with specific diagnostic testing as follows. In a visit to the clinic after discharge, the patient reported left lower limb weakness. An MRI confirmed the presence of spinal cord edema compatible with contusion more focally at T2. On the other hand, the presence of a lower trunk brachial plexopathy was confirmed by electrodiagnostic studies. Evidence of subacute denervation (positive sharp waves) was found only in the muscles innervated by the lower trunk of the brachial plexus. The absence of motor unit actions potentials (MUAPS) also suggest neurotmesis. Finally, the presence of evidence of denervation in the extensor indicis muscle confirmed the location of the injury in the lower trunk and not the medial cord. (Table 2).

Some researchers describe concomitant injuries to the spinal cord and brachial plexus as very rare and others argue that this combination is under-reported although possible after high speed motor vehicle accidents [8, 9, 11, 12]. In the civilian population GSW injuries usually present with vertebral fracture and direct involvement of the spinal cord [13]. However, penetrating bullets traveling at high speed create a shockwave that can cause cord contusion without directly passing through the spinal canal [13]. In the absence of direct trauma to the spinal cord, several mechanical factors affect the severity of a GSW injury including the type of firearm weapon, path, speed, and size of the projectile, and distance between the firearm and the target [14]. It is safe to assume that, in our patient, the path of the bullet was near the spinal canal because of the presence of a T2 vertebral fracture. This may have resulted in a spinal cord contusion due to the shockwave created by the bullet. (Fig. 1)

Incomplete spinal cord injuries like BSS may not be easily identified [8]. The presence of lower motor neuron disease may mask an even more important diagnosis of SCI that may require a different approach to acute management possibly including surgery. Even though limited information is available, the frequency of a combined injury to the spinal cord with BP has been reported to be between 0.6% and 1.8% [8]. Poor surgical outcomes have been described in patient with BSS and BPs due to a delay in the diagnosis [8]. Early on, our patient was correctly diagnosed with a left BP secondary to the GSW. Although SCI must be part of the differential diagnosis in this setting, the weakness of the lower limb was difficult to identify because our patient was unconscious. Even on day 10 the consultant did not considered the BSPS because of the unusual combination of clinical findings. This case emphasizes the need for sequential and careful observation of patients at risk of combined injuries.

Prediction of the independence and functional outcomes of a spinal cord patient is important in the creation of rehabilitation goals [9]. Little is known about how a combination of SCI and BP brachial plexopathy affects the process of rehabilitation [9]. Although SCI functional outcomes depend on the level and severity of the injury, the presence of an injury to the BP may change standard predictions [9]. BSPS is usually associated with favorable functional recovery after rehabilitation, especially if the cord is merely contused and not transected [15, 16]. However, the presence of brachial plexopathy may impede faster recovery.

As summarized in Table 1, the patient was seen in clinic 30 and 81 days after the acute trauma. On both occasions he showed improvement in muscle strength of the left lower limb but no recovery of functional capacity of the left upper limb even though a very small change in strength at C8 and T1 was noted 81 days after injury. It is possible that the nature of the spinal cord injury (i.e.; a contusion and not a section) resulted in less impairment and better outcome. However, because the patient did not come back for further appointments, we do not have information about long-term rehabilitation outcomes.

Conclusion

Diagnosis of concomitant upper and lower motor lesions is difficult in the acute trauma unit after GSW. High suspicion is needed to diagnose a BSPS combined with brachial plexopathy after GSW to the cervical region because early diagnosis is essential to overall prognosis and functional outcomes. Careful neurological examination should be performed repeatedly after any type of brachial plexopathy due to trauma to the head, neck, or cervical region.

References

Bickenbach J, Boldt I, Brinkhof M, Chamberlain J, Cripps R, Fitzharris M, et al. A global picture of spinal cord injury. In: Bickenbach J. et al (eds.) International perspectives on spinal cord injury. (WorldHealth Organization, Geneva, 2013) pp13-41.

McKinley W, Santos K, Meade M, Brooke K. Incidence and outcomes of spinal cord injury clinical syndromes. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:215–24.

Leven D, Sadr A, Aibinder WR. Brown-Séquard syndrome after a gun shot wound to the cervical spine: a case report. Spine J. 2013;13:e1–5.

Issaivanan M, Nhlane NM, Rizvi F, Shukla M, Baldauf MC. Brown-Séquard-Plus syndrome because of penetrating trauma in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2010;43:57–60.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A, et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535–46.

Fassett DR, Harrop JS, Vaccaro AR. Evidence on magnetic resonance imaging of Brown–Séquard spinal cord injury suffered indirectly from a gunshot wound. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8:286–7.

Doherty JG, Burns AS, Oferrall DM, Ditunno JF. Prevalence Of upper motor neuron vs lower motor neuron lesions in complete lower thoracic and lumbar spinal cord injuries. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25:289–92.

Rhee PC, Pirola E, He ́bert-Blouin Marie-Noëlle, Kircher MF, Spinner RJ, Bishop AT, et al. Concomitant traumatic spinal cord and brachial plexus injuries in adult patients. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2011;93:2271–7.

Kim SY, Kim TU, Lee SJ, Hyun JK. Prognosis for patients with traumatic cervical spinal cord injury combined with cervical radiculopathy. Ann Rehabil Med. 2014;38:443–9.

Nordin L, Sinisi M. Brachial plexus-avulsion causing Brown-Sequard syndrome. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2009;91-B:88–90.

Grundy DJ, Silver JR. Problems in the management of combined brachial plexus and spinal cord injuries. Int Rehabil Med. 1981;3:57–70.

Akita S, Wada E, Kawai H. Combine injuries of the brachial plexus and spinal cord. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2006;38:637–41.

Patil R, Jaiswal G, Gupta T. Gunshot wound causing complete spinal cord injury without mechanical violation of spinal axis: Case report with review of literature. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2015;6:149–57.

Jaiswal M, Mittal RS. Concept of gunshot wound spine. Asian. Spine J. 2013;7:359–64.

Roth EJ, Park T, Pang T, Yarkony GM, Lee MY. Traumatic cervical Brown-Sequard and Brown-Sequard-plus syndromes: the spectrum of presentations and outcomes. Paraplegia. 1991;29:582–9.

Little JW, Halar E. Temporal course of motor recovery after Brown-Sequard spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1985;23:39–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosario-Concepción, R.A., Pérez, J.C., Jiménez, C. et al. Delayed diagnosis of traumatic gunshot wound Brown-Sequard-plus syndrome due to associated brachial plexopathy. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 4, 44 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0075-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0075-6