Abstract

Background

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) incidence in adolescents varies widely, but has increased globally in recent years. This study reports T1D burden among adolescents and young adults aged 10–24-year-old age group at global, regional, and national levels.

Methods

Based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, we described the burden of T1D in the 10–24-year-old age group. We further analyzed these trends by age, sex, and the Social Development Index. Joinpoint regression analysis was used to assess temporal trends.

Results

T1D incidence among adolescents and young adults increased from 7·78 per 100,000 population (95% UI, 5·27–10·60) in 1990 to 11·07 per 100,000 population (95% UI, 7·42–15·34) in 2019. T1D mortality increased from 5701·19 (95% UI, 4642·70–6444·08) in 1990 to 6,123·04 (95% UI, 5321·82–6887·08) in 2019, representing a 7·40% increase in mortality. The European region had the highest T1D incidence in 2019. Middle-SDI countries exhibited the largest increase in T1D incidence between 1990 and 2019.

Conclusion

T1D is a growing health concern globally, and T1D burden more heavily affects countries with low SDI. Specific measures and effective collaboration among countries with different SDIs are required to improve diabetes care in adolescents.

Impact

-

We assessed trends in T1D incidence and burden among youth in the 10–24-year-old age group by evaluating data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

-

Our results demonstrated that global T1D incidence in this age group increased over the past 30 years, with the European region having the highest T1D incidence.

-

Specific measures and effective collaboration among countries with different SDIs are required to improve diabetes care in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing burden of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in adolescents and young adults is a major healthcare concern worldwide.1 T1D incidence in childhood and adolescence is steadily rising and now stands at 22·9 new cases per year per 100,000 children up to the age of 15 years in Germany.2 T1D burden has been attributed to rapid economic development and urbanization. The cost of diabetes care is at least 3·2 times greater than the average per capita healthcare expenditure, rising to 9·4 times in the presence of complications.3 A multicenter study in the US showed that the overall unadjusted estimated incidence rates of T1D in youths increased by 1·4% annually from 2002 to 2012.4 Thus, understanding the global burden of T1D in adolescents is important for the optimal utilization of healthcare resources in different countries.

Children are more sensitive to a lack of insulin than adults and are at a higher risk of rapid development of diabetic ketoacidosis.5 Prior studies have indicated geographic differences in T1D trends. A multicenter prospective registration study conducted in 26 European centers reported significant increases in T1D incidence among adolescents between 1989 and 2013.6 A cross-sectional multicenter study of 3.47 million youths (aged 19 years or younger) in the US found a significant increase in the estimated prevalence of T1D, from 1·48 cases per 1000 youths to 2.15 cases per 1000 youths.7 The International Diabetes Federation Atlas 10th edition reported that T1D incidence in children and adolescents varies widely, and is increasing in many nations.8 In our study, we investigated the global burden and the most substantial changes in the trend of T1D in adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years. Many countries, particularly those with a low or middle social development index (SDI), lack high-quality information regarding T1D trends in adolescents. Thus, there is an urgent need to characterize T1D burden in adolescents and provide more information to local governments to ease this burden. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019 is an international collaboration that offers an opportunity to analyze disease trends on a global scale. In this study, we aimed to analyze global trends in T1D prevalence, incidence, disability-adjusted life-year (DALY), and mortality rates among adolescents across every decade since 1990, based on the latest data from GBD 2019.

Methods

GBD 2019 provides the most up-to-date estimation of the descriptive epidemiological data including incidence, prevalence, mortality, and disability adjusted life years (DALY) on a total of 369 diseases and injuries for 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019.9 All countries and territories were classified into 21 regions according to epidemiological similarities, and could be grouped into six regions (African region, Eastern Mediterranean region, European region, Region of the Americas, South-East Asia region, and Western Pacific region) by the WHO.10 The number of incident cases, prevalent cases, deaths, and DALYs were extracted from GBD 2019. All disease estimated from GBD contains 95% uncertainty intervals (UI) for each metric, which are based on the 25th and 97.5th values of 1000 draws of the posterior distribution. Rates in our study are shown per 100 000 population. Details of data inputs, processing, synthesis, and final model are available in the accompanying GBD 2019 publications.9 The GBD database had data on T1D for different age periods. The WHO defined adolescence is the phase of life between childhood and adulthood, from ages 10 to 19. It is a unique stage for adolescents to lay the foundations of good health.11 Thus, we defined younger adolescents ages 10-14years as age subgroups, ages 15–19 could be defined older adolescent, and 20 to 24 young adults.12 To comprehensively describe the global trend of T1D in the life phase of adolescents and young adults, we defined younger adolescent (aged 10–14 years), older adolescent (aged 15–19 years), and young adults (aged 20–24 years). Data were collected from the GBD 2019 database in three age groups (10–14 years, 15–19 years, and 20–24 years), and both sexes.

The GBD 2019 analyzed the Socio-demographic index (SDI) for each country, which is an indicator estimated as a compositive of income per capita, average years of schooling among adults aged 15 and older, and fertility rate in female under 25 years old. All countries and territories were grouped into five categories based on the SDI (low SDI, low-middle SDI, middle SDI, high-middle SDI, and High SDI).

Analysis

We conducted comparisons between the sexes, age groups (three intervals; 10–14, 15–19, and 20–24 years), SDI (five categories), and WHO regions (six regions). Incidence, prevalence, death, and DALYs were reported with 95% UI to eliminate the effects caused by differences in population structures. Then, we used the Joinpoint Regression Analysis to identify the substantial changes in trends of above indicators, and we used a maximum of 5 Joinpoints as the option of analysis. We evaluated the incidence, prevalence, DALYs, and mortality trends in various countries and regions based on average annual percent change (AAPC) by Joinpoint regression analysis.13 The Joinpoint regression model was used to subsection describe disease trends from 1990 to 2019, and found out if the junctions of different segments had statistically significant. Countries with missing or zero values in their decade data were excluded from the analysis because a Joinpoint regression could not be conducted in this circumstance. The value of the AAPC is computed as a weighted average of the annual percentage change (APC) values in the regression analysis. The approximate 95% CI for AAPC was calculated by the empirical quantile method. We calculated the AAPCs between 1990 and 1999, between 2000 and 2009, between 2010 and 2009, and between 1990 and 2019. All analyses were performed using RStudio software (version R-4.2.2), and Joinpoint Regression Program (version 4.9.1.0).

Results

Global burdens of T1D in adolescents and young adults

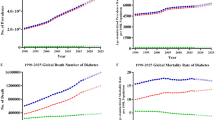

From 1990 to 2019, the incidence and prevalence of T1D in adolescents and young adults showed an overall increasing trend (Table 1). T1D incidence increased between 1990 and 1999 (AAPC, 0·88 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0·86–0·91]) and rose rapidly between 2000 and 2009 (AAPC, 1·41 [95% CI, 1·32–1·50]). The overall incidence rate in 1990 (7·78) cases per 100,000 population [95% uncertainty interval (UI), 5·27–10·60] increased to 2019 (11·07 cases per 100,000 population [95%] UI, 7·42–15·34; AAPC, 1·22 [95% CI, 1·18–1·27]). The overall global prevalence of T1D increased from 2,376,444 (95%UI 1,761,701–3,073,758) in 1990 to 364,4613 (95%UI, 2,655,059–4,756,336) in 2019, representing a 53·36% increase over the 30-year period (Table 2). Joinpoint regression analysis showed that the increasing trend of T1D incidence could be divided into six periods: 1990–1994, 1994–2001, 2001–2010, 2010–2014, 2014–2017, and 2017–2019 (Fig. 1).

From 1990 to 2019, T1D mortality and DALY rates initially exhibited an increasing trend (1990–1999), followed by a subsequent decline (Table 3). Joinpoint regression analysis identified a substantial change in both T1D mortality (in 2000, 2003, and 2014) and DALY (in 2000, 2003, and 2015) rates. T1D incidence and prevalence increased significantly during the 30-year period. The mortality rate in 2019 (0·33 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·29–0·37]) was lower than that in 1990 (0·37 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·30–0·42]; AAPC, –0·41 [95% CI, –0·60 to –0·22]). The global DALY rate significantly decreased after 2000, with the most notable decline observed between 2000 and 2003.

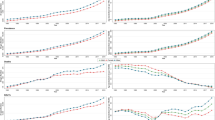

Global burdens of T1D in adolescents and young adults by sex

In the context of sex, among the 3,644,613 T1D cases among adolescents and young adults globally in 2019, 1,871,433 (53·91%) occurred in boys. Both sexes exhibited a significant increase in T1D prevalence and incidence over the 30-year period. T1D incidence in boys increased from 65,053·33 cases (95% UI, 44,514·79–87,999·81) in 1990 to 111,120·71 cases (95% UI, 75,271·16–153,830·34) in 2019, representing a 70·85% increase. T1 incidence in girls increased from 55,526·95 cases (95% UI, 37,333·90–75,781·23) in 1990 to 95,015·41 cases (95% UI, 63,469·04–132,623·84) in 2019, representing a 71·12% increase. In terms of T1D prevalence in boys, an increase from 1,206,677 cases (95% UI, 891,833·4–1,571,014) in 1990 to 1,871,433 cases (95% UI, 1,360,287·7–2,446,297) in 2019 was observed, representing a 55·09% increase. T1D prevalence in girls increased from 1,169,767 cases (95% UI, 865,724·6–1,507,234) in 1990 to 1,773,180 cases (95% UI, 1,288,764·3–2,325,674) in 2019, representing a 51·58% increase over the three decades. While the global DALY rate in boys increased (APCC, 0·28 [95% CI, 0·12–0·43]), both global mortality (APCC, -0·87 [95% CI, -1·00–-0·74]) and DALY (-0·43 [95% CI, -0·57–-0·28]) rates decreased among girls.

Global burdens of T1D in adolescents and young adults by age group

T1D trends among adolescents and young adults varied according to age. Globally, the most rapidly increasing in T1D incidence (AAPC, 1·78 [95% CI, 1·65–1·91]) and prevalence (AAPC, 0·96 [95% CI, 0·91–1·01]) over the past 30 years were observed in young adults aged 20–24 years. Despite the increase in T1D incidence and prevalence among all three age subgroups, mortality in all subgroups decreased. The largest decline in the T1D mortality rate between 1990 and 2019 was observed among older adolescents aged 15–19 years (from 0·34 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·26–0·40] to 0·29 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·24–0·33]; AAPC, -0·64 [95% CI, -0·88–-0·40]). While an increase in the DALY rate was observed among young adults aged 20–24 years (from 44·25 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 36·56–51·53] to 45·76 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 38·96–53·85]; AAPC, 0·14 [95% CI, 0·04–0·24]), a decrease was observed among those aged 10–14 years (from 25·44 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 18·23–31·77] to 23·82 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 19·36–29·81]; AAPC, -0·23 [95% CI, -0·48–0·03]) and 15–19 years (from 32·51 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 24·95–38·91] to 30·70 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 25·08–37·55]; AAPC, -0·22 [95% CI, -0·39–-0·04]) between 1990 and 2019.

Global burdens of T1D in adolescents and young adults by SDI

T1D burden among adolescents and young adults differed substantially according to the SDI. Countries with high SDI had the highest T1D prevalence (431·32 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 33·33–537·30]; AAPC, 0·70 [95% CI, 0·65–0·74]) and incidence (21·53 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 14·55–29·53]; AAPC, 1·25 [95% CI, 1·17–1·33]) rates in 2019, but the lowest mortality rate (0·16 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·14–0·16]; AAPC, -0·66 [95% CI, -0·93–-0·40]). Notably, countries with a middle SDI had the lowest T1D prevalence (151·29 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 108·62–201·91]; AAPC, 1·52 [95% CI, 1·48–1·55]) and incidence (8·58 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 5·73–11·95]; AAPC, 1·79 [95% CI, 1·74–1·84]) rates in 2019. Countries with a low SDI had the highest mortality (0·44 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·36–0·52]; AAPC, -0·41 [95% CI, -0·55–-0·28]) and DALY (39·73 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 32·90–47·47]; AAPC, -0·27 [95% CI, -0·38–-0·15]) rates in 2019. Over the past 30 years, both T1D prevalence and incidence increased across all SDI quintiles, whereas mortality rates decreased. All countries exhibited a reduction in the DALY rate from 1990 to 2019, with the exception of those countries categorized in the high SDI quintile group.

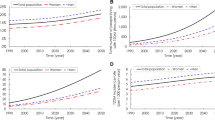

Regional and national burdens of T1D in adolescents and young adults

When classified according to World Health Organization (WHO) regions, the European region exhibited the most rapid increase in T1D incidence rate of T1D for adolescents and young adults between 1990 and 2019 (from 11·18 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 8·24–14·52] to 18·80 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 12·54–25·90]; AAPC, 1·81 [95% CI, 1·76–1·86]). The highest mortality rate in 2019 was observed in the Eastern Mediterranean region (0·43 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·34–0·53]), followed by the African region (0·40 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·33–0·48]). The Western Pacific region showed the lowest incidence (5·47 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 3·59–7·63]), prevalence (119·94 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 89·10–154·33]), mortality (0·18 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·16–0·20]), and DALY (24·61 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 20·83–28·77]) rates in 2019. The African region exhibited a modest increase in T1D incidence rate (from 10·05 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 6·73–13·93] to 10·60 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 7·07–14·87]; AAPC, 0·18 [95% CI, 0·17–0·20]) and prevalence (from 151·65 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 106·87–204·70] to 160·79 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 113·36–217·61]; AAPC, 0·20 [95% CI, 0·20–0·21]) rates between 1990 and 2019.

At the national level, Finland had the highest T1D incidence rate among adolescents and young adults in 2019 (32·56 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 22·41–44·59]; AAPC, -0·37 [95% CI, -0·78–0·04]), followed by Canada (31·89 cases per 100,000 population [95% UI, 21·83–44·01]; AAPC, 0·36 [95% CI, 0·20–0·53]) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 1–2). The Solomon Islands (1·20 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·77–1·73]; AAPC, 0·75 [95% CI, 0·47–1·03]) had the highest mortality rate in 2019, followed by Turkmenistan (1·15 deaths per 100,000 population [95% UI, 0·90–1·45]; AAPC, 2·12 [95% CI, 1·21–3·03]) (Supplementary Table 3). Despite the declining trend in the global DALY rate due to T1D, rates remained high in countries with a low SDI; Turkmenistan had the highest DALY rate in 2019 (AAPC, 1·95 [95% CI, 1·17–2·73]), followed by Haiti (87·44 per 100,000 population [95% UI, 57·16–119·46]) (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

This study provided an updated and comprehensive evaluation of global, regional, and national T1D burden among adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years old, based on data from the GBD Study 2019. Diabetes is the third most common disease in children and adolescents aged <18 years.14 Our study documented 206,136 new cases among young adult and adolescents worldwide in 2019, which led to 6123 deaths. In addition to systemic complications, T1D also has long-term effects on health-related quality of life and psychosocial functioning.15,16 Previous studies have shown that the global T1D mortality rate among adolescents has decreased with improvements in diagnosis and treatment planning.17 While we observed an overall decrease in global T1D mortality rate among adolescents between 1990 and 2019 (AAPC, –0·41 [95% CI, –0·60–-0·22]), there was also an increase between 1990 and 1999 (AAPC, 0·69 [95% CI, 0·56–0·82]). Our findings provide further insight into the global burden of the T1D epidemic among adolescents and young adults and highlight the need for government action to improve diabetes management for this age group.

Notably, our use of the SDI demonstrated a close association between T1D burden and socioeconomic development.18 Inadequate T1D diagnosis and treatment are likely to be major contributors to early mortality, especially in low-SDI countries.19 Our study showed that adolescents in countries with a greater SDI exhibited higher T1D incidence and prevalence rates in 2019, whereas middle-SDI countries had the lowest incidence and prevalence rates. Prior studies have shown that low socioeconomic status is associated with higher mortality and morbidity in adults with T1D, even in those who are capable of accessing a universal healthcare system.20 Similarly, our results indicated that the T1D mortality rate among individuals aged 10–24 years was highest in low-SDI countries. We also found that countries with a low SDI had the highest DALY rate, despite a global declining trend among adolescents between 1990 and 2019.

Previous studies have attributed geographic differences in T1D prevalence and clinical characteristics to inherent variations among ethnic groups and migration between countries.21 Our results showed that European countries had the highest T1D incidence among adolescents in 2019, whereas countries in the Western Pacific region had the lowest incidence. Prior studies have also found that T1D incidence among children aged 0–14 years differs between Nordic countries and their neighboring countries and that this may be related to differences in population density.22 A study that examined T1D incidence and trends in the 15–39-year-old age group between 1992 and 1996 in Finland concluded that the risk of T1D extended into young adulthood.23

Nonetheless, we observed that adolescents with T1D in low-SDI or developing countries tended to have higher mortality and DALY rates, which may have been due to a lack of financial support and poor diabetes management. Our results showed that the Solomon Islands had the highest T1D mortality rate in 2019, followed by Turkmenistan and Guyana. Diabetes is currently the fourth-leading cause of death in Guyana, South America.24 Multiple risk factors have been implicated in the increasing incidence of T1D among adolescents.25 Environmental factors, including childhood obesity, chronic viral infections, and maternal-child interactions, have been considered to be responsible for the current evolving pattern of T1D incidence.26 Previous studies have reported that adversities during childhood may increase the risk of T1D through hyperactivation of the stress response system, especially in individuals exposed to increasing annual rates of childhood adversities.27

There is strong evidence that sex plays an important role in T1D incidence among adolescents and young adults. Previous studies have shown that T1D incidence among children is higher in males than in females.28 A Finnish study that analyzed 3,277 children (<10 years old) diagnosed with T1D reported that boys more often had insulin autoantibody-initiated autoimmunity, whereas glutamic acid decarboxylase-initiated autoimmunity was observed more frequently in girls.29 In our study, the AAPC among females showed a declining trend compared to males, thus indicating that more attention should be paid to diabetes care for young males.

We found that age was an important factor affecting differences in the burden of T1D among adolescents and young adults. A US study estimating the total number of youth aged under 20 years with diabetes reported that T1D prevalence increased with age.30 Analysis of a national registry that included 505 hospitals in China found that the peak incidence per 100,000 person-years occurred in the 10–14-year-old age group.31 Consistent with previous studies, we observed that younger adolescents aged 10–14 years had the highest T1D incidence rate in 2019; the prevalence rate in young adults aged 20–24 years was 246·79 cases per 100,000 population, nearly twice that of younger adolescents aged 10–14 years (143·19 cases per 100,000 population). Notably, the mortality rate of T1D in 2019 among young adults was 0·49 deaths per 100,000 population, more than double that of those aged 10–14 years (0·22 deaths per 100,000 population). This is pertinent, as managing T1D in adolescents is challenging from both medical and psychosocial perspectives, due to the vulnerable period during which parental caretaking is normative and adolescent behavior is unpredictable.32

Compared with a previous GBD study that analyzed diabetes burden,33,34 we provided a more comprehensive and specific analysis of T1D among adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years and identified the most prominent changes in global trends by using Joinpoint regression analysis. Nevertheless, our study had several limitations. First, our results were based on the GBD Study 2019, which collected data from 1990 to 2019 and included countries with large boundaries. This may have been a source of significant variation in our results. Second, the determination of T1D burden in the GBD Study 2019 may have been affected by the detection method used, screening quality, and availability of local medical resources. Thus, T1D burden in countries with a low SDI tended to be underestimated, which could have introduced bias into our results. Third, while ethnic factors have been reported to affect the distribution of T1D among adolescents, these parameters were not evaluated in the GBD Study 2019.

Conclusion

T1D among adolescents and young adults is a growing global health problem, especially in countries with a low SDI and less well-developed economy. The global burden of T1D among adolescents is substantial, although mortality and DALY rates have declined over the past 30 years due to advances in healthcare. As the incidence and severity of T1D among adolescents and young adults are still increasing, there is an urgent need for the implementation of lifestyle modification programs in childhood.

Data availability

All data used in this study can be freely accessed at the GBD 2019 study (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results).

References

Henríquez-Tejo, R. & Cartes-Velásquez, R. [Psychosocial impact of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children, adolescents and their families. Literature review]. Rev. Chil. de. Pediatr. 89, 391–398 (2018).

Ziegler, R. & Neu, A. Diabetes in childhood and adolescence. Dtsch. Arzteblatt Int. 115, 146–156 (2018).

Al-Maskari, F., El-Sadig, M. & Nagelkerke, N. Assessment of the direct medical costs of diabetes mellitus and its complications in the United Arab Emirates. BMC public health 10, 679 (2010).

Mayer-Davis, E. J., Dabelea, D. & Lawrence, J. M. Incidence trends of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002–2012. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 301 (2017).

Ferguson, S. C. et al. Influence of an early-onset age of type 1 diabetes on cerebral structure and cognitive function. Diabetes care 28, 1431–1437 (2005).

Patterson, C. C. et al. Trends and cyclical variation in the incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes in 26 European centres in the 25 year period 1989-2013: a multicentre prospective registration study. Diabetologia 62, 408–417 (2019).

Lawrence, J. M. et al. Trends in prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents in the US, 2001–2017. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 326, 717–727 (2021).

Ogle, G. D. et al. Global estimates of incidence of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Atlas, 10th edition. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 183, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109083 (2022).

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (Lond., Engl.) 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

WHO. Regional officies, <https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/regional-offices> (assessed on June 2023).

WHO. Adolescent health, <https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1> (assessed on April 2023).

WHO. Older adolescent and young adukt mortality., <https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/levels-and-trends-in-older-adolescent-%2815-to-19-years%29-and-young-adult-%2820-to-24-years%29-mortality> (assessed on September 2022).

Kim, H. J., Fay, M. P., Feuer, E. J. & Midthune, D. N. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat. Med. 19, 335–351 (2000).

Crume, T. L. et al. Factors influencing time to case registration for youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Ann. Epidemiol. 26, 631–637 (2016).

Kalyva, E., Malakonaki, E., Eiser, C. & Mamoulakis, D. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM): self and parental perceptions. Pediatr. Diabetes 12, 34–40 (2011).

Monaghan, M., Bryant, B. L., Inverso, H., Moore, H. R. & Streisand, R. Young children with type 1 diabetes: Recent advances in behavioral research. Curr. diabetes Rep. 22, 247–256 (2022).

Neu, A. et al. Diagnosis, therapy and follow-up of diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes.: Off. J., Ger. Soc. Endocrinol. [] Ger. Diabetes. Assoc. 127, S39–s72 (2019).

GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950-2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (Lond., Engl.) 396, 1160–1203 (2020).

GBD 2019 Diabetes Mortality Collaborators. Diabetes mortality and trends before 25 years of age: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 10, 177–192 (2022).

Scott, A., Chambers, D., Goyder, E. & O’Cathain, A. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, morbidity and diabetes management for adults with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. PloS One 12, e0177210 (2017).

Siller, A. F. et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of diabetes type in pediatrics. Pediatr. Diabetes 21, 1064–1073 (2020).

Samuelsson, U. et al. Geographical variation in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in the Nordic countries: A study within NordicDiabKids. Pediatr. diabetes 21, 259–265 (2020).

Lammi, N. et al. A high incidence of type 1 diabetes and an alarming increase in the incidence of type 2 diabetes among young adults in Finland between 1992 and 1996. Diabetologia 50, 1393–1400 (2007).

Lowe, J. et al. The Guyana diabetes and foot care project: Improved diabetic foot evaluation reduces amputation rates by two-thirds in a lower middle income country. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 920124 (2015).

Stanescu, D. E., Lord, K. & Lipman, T. H. The epidemiology of type 1 diabetes in children. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 41, 679–694 (2012).

Xia, Y., Xie, Z., Huang, G. & Zhou, Z. Incidence and trend of type 1 diabetes and the underlying environmental determinants. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 35, e3075 (2019).

Bengtsson, J. et al. Trajectories of childhood adversity and type 1 diabetes: A nationwide study of one million children. Diabetes Care 44, 740–747 (2021).

Diaz-Valencia, P. A., Bougnères, P. & Valleron, A. J. Global epidemiology of type 1 diabetes in young adults and adults: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 15, 255 (2015).

Ilonen, J. et al. Associations between deduced first islet specific autoantibody with sex, age at diagnosis and genetic risk factors in young children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 23, 693–702 (2022).

Pettitt, D. J. et al. Prevalence of diabetes in US Youth in 2009: The SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care 37, 402–408 (2014).

Weng, J. et al. Incidence of type 1 diabetes in China, 2010–13: population based study. Br. Med. J. 360, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5295 (2018).

Pierce, J. S., Kozikowski, C., Lee, J. M. & Wysocki, T. Type 1 diabetes in very young children: a model of parent and child influences on management and outcomes. Pediatr. Diabetes 18, 17–25 (2017).

Ward, Z. J. et al. Estimating the total incidence of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents aged 0-19 years from 1990 to 2050: a global simulation-based analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 10, 848–858 (2022).

Xie, J. et al. Global burden of type 2 diabetes in adolescents and young adults, 1990-2019: systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ (Clin. Res. ed.) 379, e072385 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We appreciated the work of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 collaborators or personal relations that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China. (Grant number: 82300886), and Liaoning Revitalization Talents Program (No. XLYC2002084).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S.G. drafted and design the initial manuscript. W.Y.Y. reviewed the manuscript. Y.M.X. revised the manuscript. Z.Y.S. conceptualized, revised the manuscript. Y.X.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors have directly accessed and verified the underlying data mentioned in the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, B., Yang, W., Xing, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of type 1 diabetes in adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03107-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03107-5