Abstract

The purpose of this scoping review is to determine trends in racial and ethnic representation, identify barriers and facilitators to greater diversity, and assess strategies and interventions to advance diversity among those in the pediatric research workforce in the U.S. We conducted a scoping review of PubMed supplemented with the authors’ personal library of papers published from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2021. To be eligible, papers had to provide original data, be published in English, report information from a U.S. healthcare institution, and report on outcomes of interest relevant to the child health field. The diversity of faculty has modestly increased over the past decade but reflects a worsening representation compared to overall population trends. This slow increase reflects a loss of diverse faculty and has been referred to as a “leaky pipeline.” Strategies to plug the “leaky pipeline” include greater investments in pipeline programs, implementation of holistic review and implicit bias training, development of mentoring and faculty programs targeted to diverse faculty and trainees, alleviation of burdensome administrative tasks, and creation of more inclusive institutional environments. Modest improvements in the racial and ethnic diversity of the pediatric research workforce were identified. However, this reflects worsening overall representation given changing U.S. population demographics.

Impact

-

Racial and ethnic diversity in the pediatric research workforce has shown modest increases but worsening overall representation.

-

This review identified barriers and facilitators at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and institutional levels that impact BIPOC trainees and faculty career advancement.

-

Strategies to improve the pathway for BIPOC individuals include greater investments in pipeline and educational programs, implementation of holistic review admissions and bias training, institution of mentoring and sponsorship, alleviation of burdensome administrative responsibilities, and creation of inclusive institutional climates.

-

Future studies should rigorously test the effects of interventions and strategies designed to improve diversity in the pediatric research workforce.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The twin forces of the COVID-19 pandemic and publicized racially motivated police brutality and killings have brought into sharp focus the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the pediatric research workforce.1 As in many affected areas of society, these forces have generated renewed interest in rooting out systemic racism and promoting DEI. Research-intensive institutions, where the majority of the pediatric scientific workforce resides, have promulgated a culture of discrimination that has impeded the advancement of scientists of color.2,3 This has negatively impacted the well-being of black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) in pediatric science and hindered their productivity, retention, and promotion.

Beyond the calls for social justice, greater racial and ethnic diversity in the pediatric scientific workforce can reap well-defined benefits. Scientific teams that are composed of diverse individuals with diverse perspectives, backgrounds, and mental models are better positioned to solve complex problems among children and their families.4 In addition, students and scientific trainees who experience greater student diversity in their learning environments show greater engagement and motivation in learning and growth in intellectual and academic skills.5 Moreover, scientists from underrepresented backgrounds are more likely to engage in research with diverse groups and communities.6 This is critically important given that BIPOC children comprised 48% of the U.S. child and adolescent population in 2019 and are projected to become the majority minority in the near future.7

The purpose of this scoping review is to provide (1) a better understanding of the latest prevalence and trends in workforce representation among those conducting research in the field of pediatrics, (2) identify barriers and facilitators to greater diversity, and (3) discuss strategies and interventions which have been employed to advance diversity that can be applied to the field of child health research. This is of particular importance in pediatrics, as children and youth are generally more diverse than the overall population and are the primary driver of increasing diversity in the U.S.8

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of the Medline literature from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2021.9 To be eligible for inclusion, papers had to be (1) published in an English language peer-review journal during the study time period, (2) report information from the U.S. healthcare system, and (3) report on original research on trends, barriers and facilitators, or strategies and interventions in racial and ethnic minority representation in the pediatric scientific workforce or pipeline. Papers were excluded if they reported on a clinical or scientific specialty that did not care for children or adolescents. This scoping review was not registered.

We undertook a literature search using PubMed and searched the personal library of the authors to identify potentially eligible papers published from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2021. We chose to supplement the literature search with a search of our personal library, as we recognize that literature searches may miss potentially eligible papers due to differences in the assignment of MESH terms to published papers. For the PubMed search, we utilized the following search strategy consisting of syntax along with Boolean operators and limited the search to English:

(((“cultural diversity”[MeSH Terms] OR “diverse”[tw] OR “diversely”[tw] OR “diversities”[tw] OR “diversity”[tw]) OR (“minority groups”[MeSH Terms] OR (“minority”[tw] AND “groups”[tw]) OR “minority groups”[tw] OR (“minority”[tw] AND “group”[tw]) OR “minority group”[tw])) AND ((“Schools, Medical”[Mesh] OR medical school [tw] OR medical schools [tw]) OR (“Faculty, Medical”[Mesh] OR medical faculty [tw] OR medical faculties [tw]))) AND (“paediatrics”[All Fields] OR “pediatrics”[MeSH Terms] OR “pediatrics”[All Fields] OR “paediatric”[All Fields] OR “pediatric”[All Fields]) Filters: English, from 2010/1/1 – present

One author (J.P.G.) screened the titles and abstracts of all papers identified from the literature search and personal library to determine those that were potentially eligible. The full texts of all potentially eligible papers were pulled, and two authors (J.P.G., B.N.) independently reviewed the papers to determine eligibility. Differences in the eligibility of papers were settled by consensus in which both reviewers sought agreement on whether a disputed paper met the strict eligibility criteria described above (percent agreement 93%). Those papers for which consensus on eligibility could not be reached were excluded (n = 4).

We developed and pilot-tested a standardized abstraction form for eligible papers. We abstracted information on the citation, clinical and scientific specialties involved, level of trainees (medical students, residents, fellows), level of faculty (assistant professor, associate professor, full professor), prevalence and trends in racial and ethnic minority representation, representation metrics if applicable, facilitators and/or barriers, strategies and/or interventions, and study conclusions. Specifically, we abstracted information on the following BIPOC racial and ethnic groups if reported separately: African-American or Black, Latinx or Hispanic, Native American or Alaskan, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and Asian. We utilized additional terms including “underrepresented in medicine (URIM)” or “underrepresented minorities (URM)” to describe the results from eligible papers if these terms were specifically used in those papers, but we focused on the term BIPOC to represent all non-White individuals. Due to the variability in the reporting of results, data were not synthesized but were reported qualitatively by the study.

Results

We identified 180 potentially eligible papers from the PubMed search and an additional 86 from the library of study authors (Fig. 1). After review of the titles and abstracts, we selected 62 papers from the PubMed search and 60 papers from the study author libraries for full-text review. After a full-text review, we included a total of 52 eligible papers: 30 from the PubMed search and 22 from the library of study authors. For full-text review, potentially eligible papers were excluded for the following reasons: not reporting original research (N = 21), reporting outcomes not relevant to this review (N = 26), not U.S.-based (N = 2), and not relevant to a pediatric or child and adolescent specialty (N = 11). After the removal of 6 duplicates, we included 46 original research publications.

Prevalence, trends, and representation in pediatric research workforce diversity

We identified 13 papers reporting original data on the prevalence, population trends, and overall representation of the pediatric and child specialty workforce: 10 papers reported on the prevalence and trends in the general and pediatric workforce, while 3 papers reported on the overall representativeness of the general and pediatric research workforce.8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21

Ten of the 13 papers reported on the prevalence of diversity in the overall research workforce (Table 1). All papers showed a low prevalence of BIPOC trainees and faculty. This was consistent across pediatric and child specialties and across faculty ranks. For example, Kassam et al. reported that of surgical specialties, only trauma surgery had over 10% of division chiefs and program directors who were underrepresented minority physicians.15 The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) publishes annual figures on faculty diversity on their website.10 Their most recent data reported that the annual prevalence of underrepresented minority faculty across all departments was 9.4% and that of Asian faculty was 19.2% compared to white faculty at 63.9% in 2019. Five of the 10 papers reported specifically on pediatric faculty and trainees and found similar results with estimates ranging from 5.1 to 11.5%.8,18,19,20,21

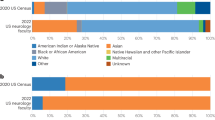

Five of the ten papers reported prevalence estimates from at least two time points. These papers uniformly reported modest increases over time in the proportions of BIPOC trainees and faculty. For example, Guevara et al. reported that the proportion of URM faculty increased only 1.2% from 6.8% in 2000 to 8.0% in 2010.13 This increase was modest among Black (3.2–3.4%) and Hispanic (3.6–4.3%) faculty but was greatest among Asian (11.2–15.0%) faculty. They also found that male sex, senior faculty rank, non-MD degree, and tenure track designation were associated with lower minority representation. Three of the five papers reported specifically on pediatric faculty and trainees, and the results were similar.18,19,21 For example, Montez et al. reported little to no increase in the proportion of pediatric trainees who were underrepresented minorities from 2007 to 2019.19 Xierali et al. reported an increase of 6.5% in the diversity of pediatric faculty, mostly among non-URM women.21

Three of the 13 papers reported on the representativeness of BIPOC trainees and faculty (Table 2). These papers used different measures of representation, yet, they were fairly consistent in their findings. Lett et al. used the S-score, a measure of the deviance of the proportion of a population subgroup from its overall proportion in the general population, and reported worsening underrepresentation of Black (–25 in 1990 to –38 in 2015) and Hispanic (–10 in 1990 to –35 in 2015) pediatric professors over time.17 Fassiotto et al. utilized the Rank Equity Index, a measure that examines population subgroups from a higher rank compared to a lower rank, and found higher levels of underrepresentation at higher faculty ranks compared to lower ranks among Black (REI 0.31 in 2007 to 0.42 in 2017) and Hispanic pediatric faculty (REI 0.57 in 2007 to 0.72 in 2017) that has changed little over time.12 Finally, Lett et al. utilized the Representation Quota, a ratio of a population subgroup’s proportion in the medical school to that in the general population, and found persistent underrepresentation of medical students over time (RQ –1.25 in 2001 to –1.45 in 2017).16

Barriers and facilitators

Nineteen papers reported on barriers and facilitators to the recruitment, promotion, and retention of BIPOC trainees and faculty (Table 3).22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 These papers used a variety of methods to report their findings including qualitative and quantitative study designs. Most were national in scope (80%) and focused on issues germane to faculty (80%). However, only five of the papers (27%) reported specifically on pediatric and child/adolescent workforce issues.27,28,29,32,37

Five of the 19 papers reported on the likelihood of recruitment and promotion of BIPOC trainees and faculty. Andriole et al. reported that among MD-PhD students, underrepresented minority and Asian students were less likely (adjusted odds ratios 0.68, 95% CI 0.48–0.98, and 0.74, 95% CI 0.60–0.93, respectively) to hold faculty positions following completion of training.23 Once they obtained faculty positions, Kaplan et al., Liu et al., and Xieraldi et al. all reported that BIPOC faculty were less likely to be promoted than white faculty.34,36,40 Associated factors included lower rates of major grant funding and publications among underrepresented minority faculty compared to white faculty.30,34 None of these five papers reported specifically on the recruitment and promotion of pediatric faculty and trainees.

Ten of the 19 papers reported on barriers to the recruitment and retention of BIPOC trainees and faculty. Barriers included intrapersonal factors such as lack of knowledge of academic requirements, educational debt and wealth differences, pressures to conform, and imposter syndrome. Interpersonal barriers were most commonly cited and included racism and discrimination, microaggressions, “angry woman characterization,” and perceptions of exclusion and isolation. Among pediatric-specific papers, Johnson et al. identified a strong pro-White anti-Black racial bias among pediatric faculty and leaders attending a diversity workshop using the Implicit Association Test.32 Similarly, Nfonoyim et al. identified microaggressions and angry characterizations of URM faculty as barriers.37 Institutional barriers were less commonly identified and included lack of adequate mentorship, a lack of minority leaders, excessive administrative responsibilities (“minority tax”), a lack of support for work–life balance, a lack of funding, and overreliance on standardized testing. For example, Williams et al. reported that USMLE Step 1 scores were lower for underrepresented minority students than for majority students, and the overweighting of these scores in residency recruitment could lead to decreased residency class diversity.39 Among pediatric-specific papers, Nfonoyim et al. and Dixon et al. identified similar institutional barriers.27,37

Eight of the 19 papers investigated potential facilitators of diversity in the pediatric and overall research workforce. Five papers reported that improved mentorship, peer and family support, minority role models, persistence, prolific writing, non-traditional funding, survival strategies, sufficient resources, and availability of pipeline programs have the potential to enhance the recruitment, retention, and promotion of BIPOC faculty.27,28,29,31,37 One paper reported on 40 medical schools with research and social missions and concluded that having an institutional mission statement that includes improving representation was associated with a higher proportion of underrepresented medical students.26 Another paper reported on URM students’ preferences in residency program matching.22 In addition, a separate paper conducted an economic evaluation and estimated that had an additional five historically black medical schools not closed following the 1910 Flexner Report, there would have been a 29% increase in black physicians in 2019.25 Results were similar among pediatric-specific papers.

Intervention strategies

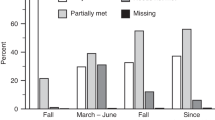

Fifteen papers reported on interventions and/or strategies to address the lack of diversity in the research workforce (Table 4).13,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54 One of these papers also reported on prevalence and trends in the section above. Four of these papers were specific to pediatrics,42,43,48,50 while the remainder were non-specific but included pediatrics. Two-thirds of the papers were national in scope, and the remainder were reports of local institutional efforts. Eight (53%) concerned interventions directed to faculty and the remainder were directed to trainees at various levels.

Two of the 15 papers concerned strategies to ameliorate unconscious bias in the recruitment and selection of applicants using holistic review.44,48 The AAMC defines holistic review as “a flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities where balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, and academic metrics to determine how the individual might contribute value as a medical student and physician.”55 These strategies are aimed at shifting an interviewer’s focus away from a candidate’s resume or board scores and toward candidate qualities that may better evaluate success within training programs have not been successful to date.56 Both papers reported the beneficial effects of holistic review on medical student and resident diversity. In pediatric-specific papers, Marbin et al. reported that a holistic review of medical student applicants increased the proportion of underrepresented minority residents.48

Four of the 15 papers examined pipeline programs aimed at undergraduates, medical students, or residents to enhance interest in future academic careers. At the level of undergraduate students, Holsti et al. write that a summer internship program targeted to American Indian and Alaskan Native college students improved the participation of these students in medical school and biomedical science research.46 At the level of medical students, Escalante et al. describe a minority scholarship program targeted to senior medical students, which improved the proportion of URM residents at a large pediatric teaching hospital.42 Similarly, Ognibene et al. report that a year-long research training program for medical students led to increased research participation and funding in their future careers.49 At the level of pediatric residents, Pachter et al. describe the impact of the New Century Scholars Program, a mentoring program targeted to URM pediatric residents, on increasing the proportion who enter academic careers.50

Eight of the 15 papers reported on intervention strategies targeted to early career faculty to enhance their career development. These programs employed a variety of strategies including mentoring, research skill development, grant funding, and leadership development. For example, the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, seeks to provide mentoring, research training, and grant support to physicians, dentists, and nurses from historically disadvantaged backgrounds early in their academic careers. An evaluation of the program found that program participants were more likely to attain leadership positions than non-participants.45 In pediatrics, the Research in Pediatrics Initiative on Diversity (RAPID), a national program of the Academic Pediatrics Association, seeks to provide mentoring, research training, and career development for URM junior pediatrics faculty. A report on RAPID reported beneficial results on graduates including increased grant productivity and promotion.43 Despite these program successes, most faculty development programs (FDP) targeted to BIPOC faculty have not been associated with improvements in minority recruitment, promotion, or overall representation.13,51 Some of the difficulties that FDPs were reported to face included a reliance on external funding, lack of sufficient mentoring time, inadequate program evaluations, and institutional challenges that limit success.41

Only a single paper focused on institutional change using the implementation of routine demographic data collection, changes in policies and procedures, and faculty development activities.54 This program reported modest improvements in URM representation (5–8%), decreases in inappropriate faculty behavior, increases in faculty job satisfaction, and improved knowledge of mentoring and university resources.

Discussion

In their 2002 report on healthcare disparities, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, the Institute of Medicine, now the National Academy of Medicine, recommended increasing the racial and ethnic diversity of the healthcare workforce.57 As such, a diverse, equitable, and inclusive pediatric research workforce is necessary to ensure success for pediatricians, academic leaders, and child health researchers.58 Over the past decade, our review has demonstrated only small incremental increases in the percentage of pediatric and other faculty who are Black, Hispanic, Native American/Alaskan Native/Native Hawaiian but larger increases for Asian faculty. Among research-oriented faculty, minority representation appears to be worse. When accounting for growth among racial and ethnic groups in the overall U.S. population, our review found that these modest increases actually reflect the increasing underrepresentation of many BIPOC groups.17 Moreover, our review found that the representativeness of medical school applicants and matriculants has changed little over time,59 which may make it difficult, if not impossible, to achieve appropriate representativeness in the pediatric workforce without substantial changes to the pipeline.

When one examines diversity along the academic pathway from trainee to early career faculty to senior career faculty and pediatric leadership positions, our review found worsening diversity.12 The paucity of diversity at the highest levels of academics is rooted in generations of racism and socioeconomic and educational inequality and has been referred to as a “leaky pipeline.” The “leaky pipeline” has been defined as “the departure of students from the path to a medical or dental career who have previously declared this intention.”60 While this definition is fitting for many experiences of BIPOC students, the academic pipeline is leaky at many critical junctures.

Our review found that BIPOC medical students report significant financial barriers that may limit their career choices in academic pediatrics. These barriers include educational debt and an overreliance on the use of standardized testing such as the USML Step 1, both of which limit their ability to pursue academic careers and grow the pipeline.28,39 This finding is consistent with education research which has found that beginning as early as high school, disparities in educational outcomes for underrepresented groups are observed on the SAT, a standardized exam often required for college entrance in the U.S. Socioeconomic status correlates with success on the SAT more than it correlates with high school grades.61,62 Another important marker of academic success, wealth, is inherently tied to one’s race when one considers the vast proportion of BIPOC children living in poverty in the United States: 30% of Native American, 31% of Black, 23% of Hispanic, and 10% of Asian children compared to 10% White non-Hispanic children.63

As one moves along in the academic pipeline, the negative influence of racial segregation becomes apparent. Racial segregation in this context refers to those factors that lead to racial exclusion in the pediatric research workforce. According to Boyd, there are four processes that lead to racial exclusion, discrimination, and segregation in the healthcare workforce: (1) white hegemony, in which decision-making power is nearly exclusively held by White people; (2) white normativity, which poses power differentials between White and non-white people as meritocratic; (3) white privilege, which preferentially allocates resources related to social and economic mobility to White people; and (4) white supremacy, which maintains the racial dominance of Whites through the ordering of humans and resources.64 Indeed, our review found that BIPOC pediatric and other faculty are recruited and promoted at lower rates than White faculty.34,36,40 Among the barriers noted, racism, discrimination, microaggressions, exclusion, and isolation were frequently identified in the studies including pediatric-specific studies.

Pipeline initiatives designed to provide educational or career support to BIPOC students have been highlighted as a mechanism to improve physician workforce diversity.65 Our review of interventions and strategies identified pipeline programs as important to achieving diversity. The programs we identified focused on trainees from undergraduates and medical students to residents and sought to stimulate interest in academic careers, develop research skills, and provide mentoring. We found that outcomes reported from pediatric-specific and more general programs have generally been favorable. For example, in a longitudinal study of career trajectories following the completion of NIH’s Clinical Research Training Program, researchers found that nearly two-thirds of participants were conducting research and over one-quarter of the participants were receiving NIH funding support.49 The importance of mentored research experiences during medical school cannot be overstated as current studies highlight the importance of “early capture” prior to completion of professional school in developing an interest in a research career.

Our review of the literature identified recruitment strategies to improve research workforce diversity. These strategies involve how we interview, rank, and match candidates into pediatric training programs. One such strategy, holistic review, has been shown to increase medical school and pediatric residency matriculant diversity while also increasing average matriculant test scores and grades.44,48 Thus, the use of a more holistic approach to select applicants for pediatric training program interviews within graduate medical education may be a better alternative.66 In applying holistic review, Guh et al. urge pediatric training programs to examine the racial/ethnic structural biases intrinsic to the processes and standards of how they recruit and select candidates.67

An additional potential recruitment strategy we identified to diversify the pediatric research workforce is antibias training. Although our review did not identify papers that evaluated the effects of antibias training in pediatrics, implicit bias and discrimination were prominently identified in our review of barriers to diversifying the pediatric research workforce. Rigorous research demonstrating the effects of antibias training in academic pediatrics is urgently needed. For example, which types of programs, platforms, and program lengths are most effective?

Our review examined strategies that seek to retain and promote BIPOC pediatric faculty.68 Included studies identified factors such as mentoring, faculty career development, research skill development, and leadership training that can advance the academic careers of BIPOC faculty. Although broad, general evaluations of FDP did not show effectiveness, we found a report that many were plagued by insecure funding streams, overtaxed faculty mentors, inadequate evaluations of their impact, and institutional challenges.41 For successful programs that were able to overcome these challenges, evaluations showed beneficial effects on program participants including enhanced scholarly productivity and leadership attainment.43,45 This was particularly true for RAPID, a pediatric program targeted to pediatric junior faculty. In addition, we found evidence that federal funding agencies like the National Institutes of Health have committed funding to diversify the research workforce, which may have a substantial impact on BIPOC trainees and faculty.52

At the same time, our review identified administrative responsibilities faced by BIPOC pediatric faculty that may interfere with their advancement. These additional responsibilities are widely known as the “minority tax.”69,70 The “minority tax” leads to BIPOC faculty disproportionately taking on roles in the diversity and other efforts that are often undervalued by institutions. This additional burden can take time away from scholarly endeavors and lead to decreased promotion rates and the departure of BIPOC faculty from academic medicine.41,71

Our review identified only a single paper on institutional approaches to enhancing faculty diversity. Institutional approaches include change in the climate and culture of an institution to promote a welcoming and inclusive environment. This paper found modest incremental improvements in the diversity of faculty. Strategic diversity interventions such as this must begin with understanding the role culture and climate play in presenting unequal opportunities for sponsorship, mentorship, and advancement of diverse faculty. Our review of barriers demonstrates that BIPOC individuals regardless of their position or stage in their career are significantly less likely to report that their learning/work environments are inclusive.72 This is consistent with prior studies that reveal that BIPOC faculty, trainees, and students report greater scrutiny over their performance and professional behavior.24,73 This paper originated from a single institution and employed a multi-tiered intervention to address faculty diversity.54 Future studies should address the impact of institutional strategies to address diversity in the pediatric and overall research workforce.

There are limitations to this scoping review. First, we relied on only a single electronic database, PubMed, to search for relevant papers. We may have missed eligible papers from a search of additional electronic databases. However, given our focus on the U.S. pediatric academic healthcare system, this restriction seemed appropriate. Second, we may have missed relevant eligible papers in our PubMed database search. Therefore, we also undertook a search of our personal libraries to identify additional eligible papers.

Conclusions

In this paper, we conducted a scoping review of the literature to understand (1) the prevalence, trends, and representativeness of the pediatric and general research workforce over the past decade; (2) barriers and facilitators to greater diversity in the pediatric and general research workforce; and (3) interventions and strategies employed to enhance diversity. While overall data suggest modest improvements in the proportion of pediatric faculty who are BIPOC, our findings suggest a worsening overall representation compared to the overall U.S. population. Given the potential benefits of a more diverse and inclusive pediatric faculty, we believe this highlights a significant and longstanding problem that limits the research, educational, and clinical mission of academic pediatrics and leads to loss of future diverse faculty.

To understand the factors that led to this underrepresentation, our scoping review has identified the metaphor of a “leaky pipeline” to describe future pediatric faculty diverting from a professed career trajectory toward a pediatric faculty position. The literature is replete with barriers that account for the “leaky pipeline” in pediatric research that reflect discrimination, segregation, and unequal opportunity as well as facilitators that can be employed to address the loss of diverse trainees and faculty. Our review of the literature suggests interventions and strategies along with data on their potential effects. These interventions and strategies address known barriers and facilitators at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and institutional levels. Future research should seek to rigorously test and understand the effects of interventions and strategies to improve diversity, especially antibias training, and institutional climate interventions, which have received little attention to date in the published literature.

References

Stolberg, S. G. Pandemic within a pandemic: coronavirus and police brutality roil black communities. New York Times (2020).

Conrad, S. S., Addams, A. N. & Young, G. H. Holistic review in medical school admission and selection: a strategic, mission-driven response to shifting societal needs. Acad. Med. 91, 1472–1474 (2016).

Witzburg, R. A. & Sondheimer, H. M. Holistic review—shaping the medical profession one applicant at a time. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1565 (2013).

Page, S. The Difference: How the Power of Diversity creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2007).

The compelling need for diversity in higher education. Mich. J. Race Law 5, 241–263 http://www.vpcomm.umich.edu/admissions/research/#um (1999).

Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine (Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington, DC, 2019).

U.S. Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. 2019 (accessed 1 December 2020); https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/00.

Walker, L. R. & Stapleton, F. B. Pediatric faculty diversity: a new landscape for academic pediatrics in the 21st century. JAMA Pediatr. 167, 989–990 (2013).

Tricco, A. C. et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473 (2018).

Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019 (accessed 31 December 2021); https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019.

Esparaz, J. R. et al. Trending diversity: reviewing four-decades of graduating fellows and the current leadership in pediatric surgery. J. Pediatr. Surg. 56, 1294–1298 (2021).

Fassiotto, M. et al. Rank Equity Index: measuring parity in the advancement of underrepresented populations in academic medicine. Acad. Med. 95, 1844–1852 (2020).

Guevara, J. P., Adanga, E., Avakame, E. & Brooks Carthon, M. Minority faculty development programs and underrepresented minority faculty representation at U.S. medical schools. JAMA 310, 2297–2304 (2013).

Higgins, M. C. et al. Underrepresentation of women and minorities in the United States IR Academic Physician Workforce. J. Vasc. Inter. Radio. 27, 1837–1844.e1832 (2016).

Kassam, A.-F., Taylor, M., Cortez, A. R., Winer, L. K. & Quillin, R. C. Gender and ethnic diversity in academic general surgery department leadership. Am. J. Surg. 221, 363–368 (2021).

Lett, E., Murdock, H. M., Orji, W. U., Aysola, J. & Sebro, R. Trends in racial/ethnic representation among US medical students. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1910490 (2019).

Lett, L. A., Orji, W. U. & Sebro, R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 U.S. medical specialties. PLoS One 13, e0207274 (2018).

Mehta, L. S. et al. Current demographic status of cardiologists in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 4, 1029–1033 (2019).

Montez, K. et al. Trends in race/ethnicity of pediatric residents and fellows: 2007-2019. Pediatrics 148, 1 (2021).

Warner, E. T., Carapinha, R., Weber, G. M., Hill, E. V. & Reede, J. Y. Considering context in academic medicine: differences in demographic and professional characteristics and in research productivity and advancement metrics across seven clinical departments. Acad. Med. 90, 1077–1083 (2015).

Xierali, I. M., Nivet, M. A. & Rayburn, W. F. Full-time faculty in clinical and basic science departments by sex and underrepresented in medicine status: a 40-year review. Acad. Med. 96, 568–575 (2021).

Agawu, A. et al. The influence of gender and underrepresented minority status on medical student ranking of residency programs. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 111, 665–673 (2019).

Andriole, D. A. & Jeffe, D. B. Predictors of full-time faculty appointment among MD-PhD program graduates: a national cohort study. Med Educ. Online 21, 30941 (2016).

Aysola, J. et al. Perceptions of factors associated with inclusive work and learning environments in health care organizations: a qualitative narrative analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 1, e181003 (2018).

Campbell, K. M., Corral, I., Infante Linares, J. L. & Tumin, D. Projected estimates of african american medical graduates of closed historically black medical schools. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2015220 (2020).

Campbell, K. M. & Tumin, D. Mission matters: association between a medical school’s mission and minority student representation. PLoS One 16, e0247154 (2021).

Dixon, G. et al. Factors that influence the choice of academic pediatrics by underrepresented minorities. Pediatrics 144, 2 (2019).

Dixon, G. et al. Factors that influence underrepresented in medicine (UIM) medical students to pursue a career in academic pediatrics. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 113, 95–101 (2021).

Flores, G. et al. Keys to academic success for under-represented minority young investigators: recommendations from the Research in Academic Pediatrics Initiative on Diversity (RAPID) National Advisory Committee. Int. J. Equity Health 18, 93 (2019).

Ginther, D. K. et al. Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science 333, 1015–1019 (2011).

Hassouneh, D., Lutz, K. F., Beckett, A. K., Junkins, E. P. & Horton, L. L. The experiences of underrepresented minority faculty in schools of medicine. Med. Educ. Online 19, 24768 (2014).

Johnson, T. J. et al. Implicit bias in pediatric academic medicine. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 109, 156–163 (2017).

Kalet, A. et al. Mentoring underrepresented minority physician-scientists to success. Acad. Med. 97, 497–502 (2022).

Kaplan, S. E. et al. Race/ethnicity and success in academic medicine: findings from a longitudinal multi-institutional study. Acad. Med. 93, 616–622 (2018).

Konuthula, D. et al. Perspectives on anti-black racism and mitigation strategies among faculty experts at academic medical centers. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e228534 (2022).

Liu, C. & Hershel, A. Promotion rates for first-time assistant and associate professors appointed from 1967 to 1997. AAMC, The Association of American Medical Colleges. 2010 (accessed 21 July 2022); http://www.lifescitrc.org/resource.cfm?submissionID=3931.

Nfonoyim, B., Martin, A., Ellison, A., Wright, J. L. & Johnson, T. J. Experiences of underrepresented faculty in pediatric emergency medicine. Acad. Emerg. Med. 28, 982–992 (2021).

Rodríguez, J., Campbell, K. & Mouratidis, R. Where are the rest of us? Improving representation of minority faculty in academic medicine. South. Med. J. 107, 739–744 (2014).

Williams, M. et al. The impact of United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) step 1 cutoff scores on recruitment of underrepresented minorities in medicine: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Health Sci. Rep. 3, e2161 (2020).

Xierali, I. M., Nivet, M. A., Syed, Z. A., Shakil, A. & Schneider, F. D. Recent trends in faculty promotion in U.S. medical schools: implications for recruitment, retention, and diversity and inclusion. Acad. Med. 96, 1441–1448 (2021).

Beech, B. M. et al. Mentoring programs for underrepresented minority faculty in academic medical centers: a systematic review of the literature. Acad. Med. 88, 541–549 (2013).

Escalante, E. et al. Increasing pediatric residency class diversity to improve patient outcomes and address structural racism. Acad. Med. 97, 850–854 (2022).

Flores, G., Mendoza, F., Brimacombe, M. B. & Frazier, W. Program Evaluation of the Research in Academic Pediatrics Initiative on Diversity (RAPID): impact on career development and professional society diversity. Acad. Med. 96, 549–556 (2021).

Grbic, D., Morrison, E., Sondheimer, H. M., Conrad, S. S. & Milem, J. F. The association between a holistic review in admissions workshop and the diversity of accepted applicants and students matriculating to medical school. Acad. Med. 94, 396–403 (2019).

Guevara, J. P., Wright, M., Fishman, N. W., Krol, D. M. & Johnson, J. The Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program: evaluation of a national program to promote faculty diversity and health equity. Health Equity 2, 7–14 (2018).

Holsti, M. et al. Lessons from the first decade of the native American summer research internship at the University of Utah. Acad. Med. 96, 522–528 (2021).

Lewis, V. et al. A randomized controlled trial of mentoring interventions for underrepresented minorities. Acad. Med. 91, 994–1001 (2016).

Marbin, J. et al. Improving diversity in pediatric residency selection: using an equity framework to implement holistic review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 13, 195–200 (2021).

Ognibene, F. P., Gallin, J. I., Baum, B. J., Wyatt, R. G. & Gottesman, M. M. Outcomes from the NIH clinical research training program: a mentored research experience to enhance career development of clinician-scientists. Acad. Med. 91, 1684–1690 (2016).

Pachter, L. M. & Kodjo, C. New century scholars: a mentorship program to increase workforce diversity in academic pediatrics. Acad. Med. 90, 881–887 (2015).

Page, K. R., Castillo-Page, L. & Wright, S. M. Faculty diversity programs in U.S. medical schools and characteristics associated with higher faculty diversity. Acad. Med. 86, 1221–1228 (2011).

Rice, T. K. et al. Mentored training to increase diversity among faculty in the biomedical sciences: the NHLBI Summer Institute Programs to Increase Diversity (SIPID) and the Programs to Increase Diversity among Individuals Engaged in Health-related Research (PRIDE). Ethn. Dis. 27, 249–256 (2017).

Tsoh, J. Y. et al. Developing faculty leadership from ‘within’: a 12-year reflection from an internal faculty leadership development program of an academic health sciences center. Med. Educ. Online 24, 1567239 (2019).

Wingard, D., Trejo, J., Gudea, M., Goodman, S. & Reznik, V. Faculty equity, diversity, culture and climate change in academic medicine: a longitudinal study. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 111, 46–53 (2019).

Anonymous. Holistic Review. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2021 (accessed 23 April 2021); https://www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review#top.

Gordon, E. K. B. et al. The role of the interview in residency selection: a mixed methods study. Med. Educ. 54, 1029–1039 (2020).

Smedley, B. D., Stith, A. Y., Nelson, A. R. eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. (Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 2002).

Mendoza, F. S., Fuentes-Afflick, E. & Walker-Harding, L. R. Diversity and inclusion in pediatrics: imperative, not optional. Pediatr. Res. 86, 558–559 (2019).

Lett, L. A., Murdock, H. M., Orji, W. U., Aysola, J. & Sebro, R. Trends in racial/ethnic representaton among U.S. medical students. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1910490 (2019).

Barr, D. A. et al. The leaky pipeline: factors associated with early decline in interest in premedical studies among underrepresented minority undergraduate students. Acad. Med. 83, 503–511 (2008).

Sackett, P. R., Kuncel, N. R., Ameson, J. J., Cooper, S. R. & Waters, S. D. Socioeconomic Status and the Relationship between the SAT and Freshman GPA: An Analysis of Data from 41 Colleges and Universities. Research Report 2009-1 (The College Board, New York, 2009).

Geiser, S. The Growing Correlation between Race and SAT Scores: New Findings from California (Center for Studies in Higher Education, Berkeley, CA, 2015).

Kids Count Data Center. Children in Poverty by Race and Ethnicity in the United States, 2010-2019. Annie E Casey Foundation (accessed 2020); https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/44-children-in-poverty-by-race-and-ethnicity#detailed/1/any/false/1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133/10,11,9,12,1,185,13/324,323.

Boyd, R. W. The case for desegregation. Lancet 393, 2484–2485 (2019).

Sullivan Commission. Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions—A Report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce (Sullivan Commission, Washington, DC, 2004).

Williams, C. et al. A call to improve conditions for conducting holistic review in graduate medical education recruitment. Mededpublish 8, 6 (2019).

Guh, J., Harris, C. R., Martinez, P., Chen, F. M. & Gianutsos, L. P. Antiracism in residency: a multimethod intervention to increase racial diversity in a community-based residency program. Fam. Med. 51, 37–40 (2019).

Adanga, E., Avakame, E., Brooks Carthon, M. & Guevara, J. P. An environmental scan of faculty diversity programs at U.S. medical schools. Acad. Med. 87, 1540–1547 (2012).

Campbell, K. M. et al. Releasing the net to promote minority faculty success in academic medicine. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disp. 7, 202–206 (2020).

Rodriguez, J. E. et al. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med. Educ. 15, 6 (2015).

Blackstock, U. Why black doctors like me are leaving academic medicine. STAT (16 January 2020).

Aysola, J., Harris, D., Huo, H., Wright, C. S. & Higginbotham, E. Measuring organizational cultural competence to promote diversity in academic healthcare organizations. Health Equity 2, 316–320 (2018).

Alexis, D. A. et al. Assessment of perceptions of professionalism among faculty, trainees, staff, and students in a large university-based health system. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2021452 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Michael Luethke for his assistance in pulling the full text of potentially eligible papers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.G., J.A., R.W., B.N., and K.N.C. conceptualized the study. M.Q. conducted the literature search. M.R. pulled the full text of the papers and abstracted the data. All authors participated in drafting and editing of the manuscript, and approved the final version submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Guevara, J.P., Aysola, J., Wade, R. et al. Diversity in the pediatric research workforce: a scoping review of the literature. Pediatr Res 94, 904–914 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02603-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02603-4