Abstract

Backgrounds

Japanese studies on the association between maternal alcohol consumption and fetal growth are few. This study assessed the effect of maternal alcohol consumption on fetal growth.

Methods

This prospective birth cohort included 95,761 participants enrolled between January 2011 and March 2014 in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Adjusted multiple linear and logistic regression models were used to assess the association between prenatal alcohol consumption and infant birth size.

Results

Consumption of a weekly dose of alcohol in the second/third trimester showed a significant negative correlation with standard deviation (SD; Z) scores for body weight, body length, and head circumference at birth, respectively. Consumption of a weekly dose of alcohol during the second/third trimester had a significant positive correlation with incidences of Z-score ≤ −1.5 for birth head circumference. Associations between alcohol consumption in the second/third trimester and Z-score ≤ −1.5 for birth weight or birth length were not significant. Maternal alcohol consumption in the second/third trimester above 5, 20, and 100 g/week affected body weight, body length, and head circumference at birth, respectively.

Conclusion

Low-to-moderate alcohol consumption during pregnancy might affect fetal growth. Public health policies for pregnant women are needed to stop alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

Impact

-

This study examined the association between maternal alcohol consumption and fetal growth restriction in 95,761 pregnant Japanese women using the prospective birth cohort.

-

Maternal alcohol consumption in the second/third trimester more than 5, 20, and 100 g/week might affect fetal growth in body weight, body length, and head circumference, respectively.

-

The findings are relevant and important for educating pregnant women on the adverse health effects that prenatal alcohol consumptions have on infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol consumption among young women is a habit that may continue after conception. In Japanese data on alcohol consumption during pregnancy, planned pregnancies were not considered; this may have altered the rate of alcohol consumption at conception. However, a cross-sectional study of pregnant Japanese women who were receiving antiepileptic drugs reported a planned pregnancy rate of 35.9%1. In 2002, 76.9% of pregnant Japanese women abstained from alcohol after the confirmation of pregnancy2. In a survey by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, the rate of alcohol consumption among pregnant women who knew that they were pregnant was 8.7%3. In the birth cohort study, the Japan Environmental and Children’s Study (JECS), the rate of alcohol consumption among pregnant women before and after awareness of pregnancy was 50.0% and 2.8%, respectively4. In the JECS, the median (inter-quartile range) quantity of alcohol consumed before and after awareness of pregnancy was reported as 27.1 (11.6–74.5) and 10.6 (4.6–21.5) g/week, respectively4. Women of childbearing age consume more alcohol than those of non-childbearing age. This increasing rate of alcohol consumption among young women remains a potential problem in future. Therefore, it is important to examine the association between maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and birth outcomes among pregnant women in Japan.

In addition, the effect of maternal alcohol exposure on fetal growth remains controversial, even according to the result of the most recent meta-analysis5. Some retrospective studies reported a negative effect of maternal alcohol consumption on birth weight6,7, while some prospective or case–control studies showed no such effect8,9. Potential confounders of alcohol consumption, such as smoking, maternal physical and socioeconomic status, and premature birth affect birth weight significantly. Some reports mentioned that patterns of prenatal alcohol use influence fetal growth outcomes10.

Five reports have assessed the relationship between prenatal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and birth weight or small-for-gestational-age (SGA) status in Japan11,12,13,14,15. In a prospective birth-cohort study of the Hokkaido Study on Environment and Children’s Health, alcohol consumption during pregnancy was a risk factor for SGA among full-term infants (term-SGA) born to 18,509 pregnant Japanese women15. However, the other four studies revealed no association among 189–23,132 participants. The discrepancy in the five previous reports from the Japanese population may be due to the limited sample size and varied levels of alcohol consumption. Studies on the association between the threshold of prenatal alcohol consumption and SGA and birth weight in Japan are limited. Thus, there is a need to re-examine the relationship between prenatal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and birth size or SGA among Japanese women, whose alcohol consumption habits differ from that of Europeans and Americans by conducting a prospective birth cohort study with a sample size of ≥20,000 participants. Based on previous knowledge, we hypothesized that (i) alcohol consumption among pregnant Japanese women would reduce birth weight and increase the risk of SGA among their infants and (ii) a low-to-moderate alcohol consumption habits during pregnancy would increase the risk of small birth sizes and SGA.

Maternal alcohol consumption is assessed using the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Ethanol is the main component of alcohol; it is oxidized to acetaldehyde by the enzyme, alcohol dehydrogenase, and much of the acetaldehyde is oxidized to acetate by the enzyme, aldehyde dehydrogenase. A large amount of acetate leaves the liver and circulates to the peripheral tissues16. Alcohol and acetaldehyde, which is a more toxic metabolite of ethanol, has adverse effects on birth size, preterm birth, and SGA17,18,19. The half-lives of ethanol and acetaldehyde in humans are about 1.5–2.5 and 1.5–3 h, respectively20,21. The short half-lives of ethanol and acetaldehyde imply that a single measurement of maternal ethanol and acetaldehyde levels at a specific time point may not be suitable to evaluate alcohol consumption during pregnancy. The FFQ quantifies alcohol consumption and offers an accurate estimation of alcohol consumption.

The aim of this study was to assess the effect of maternal alcohol consumption on fetal growth after adjusting for the effect of confounding factors using a nationwide birth cohort.

Methods

Study participants

The JECS is an ongoing prospective birth cohort study in Japan. Details of the JECS have been described elsewhere22,23. Pregnant women were recruited between January 2011 and March 2014. Pregnant women who lived in the study area at the time of recruitment, had an expected date of delivery after August 2011, understood Japanese, and were able to complete the self-administered questionnaire were eligible for the study. Pregnant women residing outside the study area who sought antenatal care at participating health care facilities within the study area were excluded. In total, 104,102 birth records were included in the cohort, including records of multiple births. The present study used the dataset jecs-ag-20160424 which was released in June 2016 and revised in October 2016.

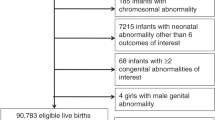

The exclusion criteria included stillbirth and miscarriage (n = 3954); multiple birth (n = 1889); severe anomalies (n = 327); infants with gestational ages <34 weeks (n = 956); infants with gestational ages ≥42 weeks (n = 224); and incomplete data on parity (n = 917), birth weight (n = 68), and infant sex (n = 6). Among the 104,102 fetal records included in the cohort, data of singleton live births without severe anomalies and any exclusion criterion were available for 95,761 fetal records. The participant selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Ethical statement

The JECS protocol was approved by the Ministry of the Environment’s Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological Studies and by the ethics review committees of each participating institution (Appendix 1). All the participants provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Questionnaires including FFQ

Maternal age, maternal pre-pregnancy body weight and height, and hard work status were assessed via a self-administered questionnaire during the first trimester (10–16 weeks of gestation). Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the pre-pregnancy weight (kg) by the square of the pre-pregnancy height (m2). Information on the highest maternal education level, family income, maternal active and passive smoking status, and psychological problems (slightly anxious, depression, or frustration) was obtained via a self-administered questionnaire during the second/third trimester (20–28 weeks of gestation). The self-administered FFQ was used to obtain information on consumption of alcoholic beverages during both the first (10–16 weeks of gestation) and second/third (20–28 weeks of gestation) trimesters. Details of the self-administered FFQs used in this study have been described previously24. Details of mild or severe hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), birth size, gestational age, and infant sex were obtained via the questionnaire, which was written by medical doctors and was based on birth medical records.

Calculations of weekly alcohol consumption

The FFQ was used to estimate alcohol consumption. We calculated the average daily alcohol consumption (in grams) for regular drinkers based on the beverage type, frequency of alcoholic beverage consumption, and the quantity consumed per occasion using the previously reported alcohol conversion chart18.

The questionnaire contained queries on the consumption of popular alcoholic beverages in Japan, including Japanese sake (rice wine), shochu (distilled spirit), and awamori (strong Okinawan liquor distilled from rice or millet), beer, whiskey, and wine. The frequency of alcohol consumption during pregnancy was classified into six categories: rarely/never, once to thrice per month, once to twice per week, three to four times per week, five to six times per week, and once per day. The quantity of Japanese sake and shochu/awamori consumed per occasion was classified into eight categories: never, <0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5–6, or ≥7 go (in Japan, the go is the most commonly used measurement of Japanese sake and shochu/awamori consumption; they contain approximately 23 and 36 g of alcohol, respectively. One go of Japanese sake is equivalent to 180 mL). The quantity of beer consumed per occasion was classified into eight categories: never, <0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5–6, and ≥7 bottles. One bottle of beer is approximately 633 mL and contains approximately 23 g of alcohol. The quantity of whiskey consumed per occasion was classified into eight categories: never, <0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5–6, and ≥7 shots. One shot of whiskey contains approximately 30 mL and 10 g of alcohol. The quantity of wine consumed per occasion was classified into eight categories: never, <0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5–6, and ≥7 glasses. One glass of wine contains approximately 60 mL and 9 g of alcohol. We calculated the amount of alcohol consumed per week by multiplying the amount consumed per occasion for each beverage type by the frequency consumed per day and multiplying the result by 7 (days).

Women in the first trimester of pregnancy who answered, “I don’t take alcoholic beverages innately” or “I have quitted alcohol” were considered non-alcohol drinkers, and those who answered, “I take alcoholic beverages” were considered alcohol drinkers. Women in the second/third trimester who answered, “I don’t take alcoholic beverages innately” or “I quitted alcohol before or after being aware of the pregnancy” were considered non-alcohol drinkers, and those who answered, “I take alcoholic beverages” were considered alcohol drinkers.

Outcome definitions

The weight, length, and head circumference of each infant measured at birth were defined as birth weight, birth length, and birth head circumference, respectively. Each birth weight, birth length, or birth head circumference Z-score was defined as the respective standard deviation (SD) for gestational age in the normal distribution, accounting for infant sex, maternal parity, and gestational age according to the guidelines of the Japan Pediatric Society25,26. SGA was defined as a Z-score of birth weight below −1.5 SD. A Z-score of birth length <−1.5 was defined as a Z-score of birth length below −1.5 SD. A Z-score of birth head circumference <−1.5 was defined as a Z-score of birth head circumference below −1.5 SD.

Statistical analyses

First, we assessed the maternal characteristics and alcohol drinking status in the first and second/third trimesters. Second, we compared the characteristics between mothers of SGA infants and those of non-SGA infants using the chi-square test and independent t-test. The chi-square test was used to test the difference in frequency between the SGA and non-SGA groups. An independent t-test was used to compare the mean difference between the SGA and non-SGA groups. Third, we assessed the association between alcohol drinking in the second/third trimester and each Z-score of birth weight, birth length, or birth head circumference using multiple linear regression models adjusted for maternal age (≥35/<35 years), education level (≤high school/>high school), annual household income (<4/≥4 million Japanese yen), pre-pregnancy BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 (yes/no), pre-pregnancy BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (yes/no), hard work in the first trimester (yes/no), maternal active and passive smoking in the second/third trimester (yes/no), psychological problems in the second/third trimester (yes/no), and mild or severe HDP (yes/no). A multiple regression analysis was used to quantify the associated factors (explanatory variables) in the form of functions, and to predict the results (objective variables [continuous variables of the Z-score for birth size]) based on the associated factors. Fourth, we assessed the association between alcohol consumption in the second/third trimester and SGA, Z-score of birth length < −1.5, or Z-score of birth head circumference < −1.5 using logistic regression models adjusted for the above-mentioned confounding factors. A logistic regression analysis was used to quantify the associated factors (explanatory variables) in the form of functions and to predict the results (objective variables [binary variables of whether Z-score for birth size < −1.5 or not]) based on the associated factors. Finally, we assessed the association between each Z-score of birth weight, birth length, or birth head circumference of infants born to alcohol drinkers and non-alcohol drinkers using the independent t-test to assess the effect of threshold alcohol levels on the reduction in birth size;. that is, the independent t-test was used to test the difference in the mean birth size of infants born to non-alcohol drinkers and alcohol drinkers with more than a certain amount of alcohol. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The maternal characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The proportions of mothers aged ≥35 years, those with a high school educational level, those with family incomes of 4–8 million Japanese yen, those with maternal pre-pregnancy BMIs <18.5 kg/m2, those with pre-pregnancy BMIs ≥25 kg/m2, those who engaged in hard work during the first trimester, those who smoked in the second/third trimester, those with maternal passive smoking in the second/third trimester, those who had psychological problems in the second/third trimester, those with mild HDP, and those with severe HDP were 26.88%, 35.57%, 44.76%, 16.16%, 10.59%, 13.71%, 4.48%, 59.40%, 76.45%, 2.23%, and 0.81%, respectively.

The participants’ alcohol consumption statuses in the first and second/third trimesters are shown in Table 2. The number of alcohol drinkers in the first and second/third trimesters was 9,375 (9.79%) and 2,642 (2.76%), respectively. In the first trimester, the number of women who drank alcohol less than once/week, every day, less than 10 g per occasion, ≥200 g per occasion, less than 5 g per week, and ≥100 g per week was 4,074 (43.46%), 1,110 (11.84%), 5,173 (55.18%), 43 (0.46%), 4,833 (51.55%), and 1,170 (12.68%), respectively. In the second/third trimester, the number of women who drank alcohol less than once/week, every day, less than 10 g per occasion, ≥200 g per occasion, less than 5 g per week, and ≥100 g per week was 1,692 (64.04%), 75 (2.84%), 504 (19.08%), 4 (0.15%), 872 (33.01%), and 133 (5.03%), respectively.

Table 3 shows the differences between SGA and non-SGA infants. Compared with mothers of non-SGA infants, a higher proportion of mothers of SGA infants had education levels up to high school (38.4% vs. 36.3%; p = 0.003), engaged in hard work in the first trimester (15.5% vs. 14.0%; p = 0.005), smoked in the first trimester (21.7% vs. 17.8%; p < 0.001), smoked in the second/third trimester (8.4% vs. 4.4%; p < 0.001), had psychological problems in the second/third trimester (79.5% vs. 77.9%; p = 0.010), mild HDP (4.7% vs. 2.1%, p < 0.001), severe HDP (3.0% vs. 0.7%; p < 0.001), and drank alcohol in the second/third trimester (3.6% vs. 2.8%; p = 0.001). In the second/third trimester, compared with mothers of non-SGA infants who drank alcohol, mothers of SGA infants drank alcohol more frequently (0.040 vs. 0.026 times/week; p = 0.019), and had a higher alcohol consumption dose per occasion (0.771 vs. 0.502 g; p = 0.005).

Table 4 shows the association between maternal alcohol consumption dose (10 g) per week in the second/third trimester and Z-score and incidence of Z-score < −1.5 for body size. Ten grams of maternal alcohol consumption per week decreased 0.005 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.001, 0.009; p = 0.021), 0.006 (0.002, 0.010; p = 0.008), and 0.005 (0.001, 0.009; p = 0.026) Z-score for birth weight, birth length, and birth head circumference, respectively. Ten grams of alcohol consumption per week increased the risk of Z-score for birth head circumference < −1.5 by 1.015 (1.004, 1.026; p = 0.009). Ten grams of alcohol consumption dose per week in the second/third trimester did not significantly influenced the incidence of Z-score < −1.5 for birth weight and birth length.

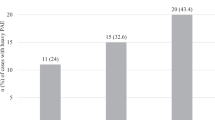

Table 5 shows the association between ≥ threshold levels of alcohol consumption in the second/third trimester and no alcohol consumption for birth outcomes. Compared to infants of mothers with non-alcohol drinkers, those of alcohol drinkers who consumed ≥5 g/week had significantly lower Z-scores for birth weight (0.072 ± 0.965 vs. 0.141 ± 0.960; p = 0.022); those of alcohol drinkers who consumed ≥20 g/week had significantly lower Z-scores for birth length (0.751 ± 0.977 vs. −0.045 ± 1.021; p = 0.005); and those of alcohol drinkers who consumed ≥100 g/week had significantly lower Z-scores for birth head circumference (−0.004 ± 1.013 vs. −0.235 ± 1.049; p = 0.009), respectively.

Discussion

This study showed that maternal alcohol consumption during the second/third trimester was significantly associated with lower Z-scores for birth weight, birth length, and birth head circumference, and with a higher incidence of Z-scores < −1.5 SD for birth head circumference. In our previous study, alcohol consumption during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of a birth weight < the 10th percentile of infants at term.15 In the present study, SGA was defined as a birth weight <−1.5 SD which is equivalent to < the 6.7th percentile. Low birth weight is correlated with prematurity, sex, and SGA. In this study, we converted birth weight, birth length, and birth head circumference to Z-scores.

In a previous large study, heavy and low-to-moderate maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy was associated with lower birth weights, and higher risks of low birth weight and SGA27,28. In this study, we also observed that mothers with a low dose of alcohol consumption (≥5 g ethanol or ≥1/2 shot of whisky per week) in the second/third trimester had infants with lower birth weights. These findings are similar to those of previous studies27,28. Even if the pregnant women had consumed low levels of alcohol during pregnancy, the infants born to the women would have being at risk of a reduction in birth weight.

The present study showed that maternal consumption of ≥20 g alcohol/week and ≥100 g alcohol/week in the second/third trimester might decrease the birth length and birth head circumference, respectively. A small birth head circumference has been strongly associated with low cognitive ability in adolescents29. A small birth head circumference may reflect the correlation between maternal alcohol consumption and impaired cognitive ability in the offspring30.

Mothers with heavy alcohol consumption habits but not low-to-moderate consumption habits during the first, second, and third trimesters had a higher risk of SGA infants than non-alcohol drinkers17,31. In this study, we observed that maternal alcohol consumption in the second/third but not the first trimester decreased the Z-score for birth weight, birth length, and birth head circumference. The increased risk of SGA reported in previous studies might not be due to the timing but the great quantity of alcohol consumed.

Infants with SGA often overlap with those born prematurely32,33. Mothers who consumed alcohol above low levels during the first trimester but abstained in the second and third trimesters had a 1.8-fold increased risk of preterm birth compared to pregnant women who did not consume alcohol during the first trimester34. In a previous study conducted using the JECS data, a J-shaped association was observed between alcohol consumption in the second and third trimesters and risk of preterm birth while there was no association in the first trimester18.

The mechanism of the association between alcohol consumption and the high risk of SGA is unknown. Oxidative stress and DNA damage are mechanisms of underlying fetal alcohol spectrum disorders35. Alcohol and/or acetaldehyde might directly affect fetal growth or indirectly suppress fetal growth via placental dysfunction.

This study had some strengths. First, this prospective birth cohort study had a large sample size of 95,761 participants. Second, the relatively homogeneous cohort of participants comprised pregnant Japanese women who were exposed to alcohol, allowing for a heterogeneous and broad distribution of alcohol consumption in a relatively large sample.

However, this study also has several limitations. First, alcohol consumption in pregnancy assessed using the FFQ might result in an underestimation of consumption levels since they were self-administered by the pregnant women. People who describe themselves as less frequent drinkers tend to under-report their drinking frequency substantially36. We relied on maternal recall of alcohol consumption. These may have resulted in biased estimates. Second, potential genetic, placental, physiologic, and nutritional factors may all affect both exposure and outcomes. Not many potential covariates were collected or assessed for the variation with fetal growth during the entire pregnancy; these factors could be confounders.

Although SGA infants who do not catch up their growth have a risk of short stature, those who catch up their growth early have an increased risk of obesity37. However, it is unknown whether SGA children born to mothers who drink alcohol during pregnancy catch up their growth and become obese during childhood. Future studies involving this birth cohort will assess the associations between SGA children born to mothers with low-to-moderate levels of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and catch-up growth trajectory after birth or increased risk of childhood obesity.

Conclusions

We found that low-to-moderate alcohol consumption during pregnancy lowers birth weight, birth length, and birth head circumference among Japanese women. In addition, alcohol consumption during pregnancy affects the risk of Z-score for head circumference <−1.5 SD. Due to insufficient adjustment for potential confounding factors, the generalizability of these findings is limited. Public health policies for pregnant women should encourage no alcohol consumption throughout pregnancy due to the increased risk of adverse health effects with low-to-moderate alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

References

Ikeda-Sakai, Y. et al. Inadequate folic acid intake among women taking antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy in Japan: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 9, 13497 (2019).

Yamamoto, Y. et al. Alcohol consumption and abstention among pregnant Japanese women. J. Epidemiol. 18, 173–182 (2008).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Japan 2010 e-health net (in Japanese; cited 2019.10.11); https://www.e-healthnet.mhlw.go.jp/information/alcohol/a-06-002.html.

Ishitsuka, K. et al. Determinants of alcohol consumption in women before and after awareness of conception. Matern. Child Health J. 24, 165–176 (2020).

Pereira, P. P. D. S., Mata, F. A. F. D., Figueiredo, A. C. M. G., Silva, R. B. & Pereira, M. G. Maternal exposure to alcohol and low birthweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 41, 333–347 (2019).

Oster, R. T. & Toth, E. L. Longitudinal rates and risk factors for adverse birth weight among first nations pregnancies in Alberta. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 38, 29–34 (2016).

Silva, I. D., Quevedo Lde, A., Silva, R. A., Oliveira, S. S. & Pinheiro, R. T. Association between alcohol abuse during pregnancy and birth weight. Rev. Saude Publ. 45, 864–869 (2011).

Witt, W. P. et al. Infant birthweight in the US: the role of preconception stressful life events and substance use. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 19, 529–542 (2016).

Mariscal, M. et al. Pattern of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and risk for low birth weight. Ann. Epidemiol. 16, 432–438 (2006).

Bandoli, G. et al. Patterns of prenatal alcohol use that predict infant growth and development. Pediatrics 143, e20182399 (2019).

Maruoka, K. et al. Risk factors for low birthweight in Japanese infants. Acta Paediatr. 87, 304–309 (1998).

Ogawa, H. et al. Passive smoking by pregnant women and fetal growth. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 45, 164–168 (1991).

Nagata, C., Iwasa, S., Shiraki, M., Sahashi, Y. & Shimizu, H. Association of maternal fat and alcohol intake with maternal and umbilical hormone levels and birth weight. Cancer Sci. 98, 869–873 (2007).

Miyake, Y., Tanaka, K., Okubo, H., Sasaki, S. & Arakawa, M. Alcohol consumption during pregnancy and birth outcomes: the Kyushu Okinawa maternal and child health study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14, 79 (2014).

Tamura, N. et al. Different risk factors for very low birth weight, term-small-for-gestational-age, or preterm birth in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, E369 (2018).

Cederbaum, A. I. Alcohol metabolism. Clin. Liver Dis. 16, 667–685 (2012).

Cooper, D. L., Petherick, E. S. & Wright, J. The association between binge drinking and birth outcomes: results from the born in Bradford cohort study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 67, 821–828 (2013).

Ikehara, S. et al. Association between maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and risk of preterm delivery: the Japan environment and children’s study. BJOG 126, 1448–1454 (2019).

Feldman, H. S. et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure patterns and alcohol-related birth defects and growth deficiencies: a prospective study. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 36, 670–676 (2012).

Auty, R. M. & Branch, R. A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ethanol, whiskey, and ethanol with n-propyl, n-butyl, and iso-amyl alcohols. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 22, 242–249 (1977).

Ohlin, H., Brattström, L., Israelsson, B., Bergqvist, D. & Jerntorp, P. Atherosclerosis and acetaldehyde metabolism in blood. Biochem. Med. Metab. Biol. 46, 317–328 (1991).

Kawamoto, T. et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). BMC Public Health 14, 25 (2014).

Michikawa, T. et al. Baseline profile of participants in the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). J. Epidemiol. 28, 99–104 (2018).

Yokoyama, Y. et al. Validity of short and long self-administered food frequency questionnaires in ranking dietary intake in middle-aged and elderly Japanese in the Japan public health center-based prospective study for the next generation (JPHC-NEXT) protocol area. J. Epidemiol. 26, 420–432 (2016).

Itabashi, K., Miura, F., Uehara, R. & Nakamura, Y. New Japanese neonatal anthropometric charts for gestational age at birth. Pediatr. Int. 56, 702–708 (2014).

Itabashi, K. et al. Introduction of the new standard for birth size by gestational ages. (in Japanese). J. Jpn Pediatr. Soc. 114, 1271–1293 (2010).

Patra, J. et al. Dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of low birthweight, preterm birth and small for gestational age (SGA)—a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG 118, 1411–1421 (2011).

Strandberg-Larsen, K. et al. Association of light-to-moderate alcohol drinking in pregnancy with preterm birth and birth weight: elucidating bias by pooling data from nine European cohorts. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 32, 751–764 (2017).

Jensen, R. B., Juul, A., Larsen, T., Mortensen, E. L. & Greisen, G. Cognitive ability in adolescents born small for gestational age: associations with fetal growth velocity, head circumference and postnatal growth. Early Hum. Dev. 91, 755–760 (2015).

Sanou, A. S. et al. Maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and child’s cognitive performance at 6-8 years of age in rural Burkina Faso: an observational study. PeerJ 5, e3507 (2017).

Chiaffarino, F. et al. Alcohol drinking and risk of small for gestational age birth. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 60, 1062–1066 (2006).

Kobayashi, S. et al. Dose-dependent associations between prenatal caffeine consumption and small for gestational age, preterm birth, and reduced birthweight in the Japan environment and children’s study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 33, 185–194 (2019).

Kobayashi, S. et al. Association of blood mercury levels during pregnancy with infant birth size by blood selenium levels in the Japan environment and children’s study: a prospective birth cohort. Environ. Int. 125, 418–429 (2019).

O’Leary, C. M., Nassar, N., Kurinczuk, J. J. & Bower, C. The effect of maternal alcohol consumption on fetal growth and preterm birth. BJOG 116, 390–400 (2009).

Bhatia, S., Drake, D. M., Miller, L. & Wells, P. G. Oxidative stress and DNA damage in the mechanism of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Birth Defects Res. 111, 714–748 (2019).

Stockwell, T. et al. Estimating under- and over-reporting of drinking in national surveys of alcohol consumption: identification of consistent biases across four English-speaking countries. Addiction 111, 1203–1213 (2016).

Nam, H. K. & Lee, K. H. Small for gestational age and obesity: epidemiology and general risks. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 23, 9–13 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the individuals who participated in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. We express our sincere appreciation to the collaborating hospitals and clinics. We also express our gratitude to the members of staff of the Hokkaido, Miyagi, Fukushima, Chiba, Kanagawa, Koshin, Toyama, Aichi, Kyoto, Osaka, Hyogo, Tottori, Kochi, Fukuoka, and Minami-Kyushu and Okinawa Regional Centers, Program Office, and Medical Support Center for the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (Appendix 1). The Japan Environment and Children’s Study is funded by the operating budget of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Ministry of the Environment of the Japanese government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

K.C., S.K., A.A., S.I., H.M., and R.K. conceived and designed the study. K.C., S.K., A.A., C.M., S.I., Y.S., Y.I., K.S., T.B., H.M., and R.K. performed the data collection. K.C., S.K., A.A., S.I., and R.K. performed the statistical analysis and contributed the manuscript preparation and literature search. S.K., A.A., S.I., H.M., and R.K. interpreted the data. S.K., A.A., C.M., S.I., Y.S., Y.I., Y.N., and R.K. contributed the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Y.S., Y.I., K.S., and R.K. contributed the funds collection and was supervisor of the study. All authors approved the version of the manuscript to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Patient consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants (patients).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, K., Kobayashi, S., Araki, A. et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure and adverse fetal growth restriction: findings from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Pediatr Res 92, 291–298 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01595-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01595-3