Abstract

Background

Hypothesis: neuromotor development correlates to body composition over the first year of life in prematurely born infants and can be influenced by enhancing motor activity.

Methods

Forty-six female and 53 male infants [27 ± 1.8 (sd) weeks] randomized to comparison or exercise group (caregiver provided 15–20 min daily of developmentally appropriate motor activities) completed the year-long study. Body composition [lean body and fat mass (LBM, FM)], growth/inflammation predictive biomarkers, and Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) were assessed.

Results

AIMS at 1 year correlated with LBM (r = 0.32, p < 0.001) in the whole cohort. However, there was no effect of the intervention. LBM increased by ~3685 g (p < 0.001)); insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) was correlated with LBM (r = 0.36, p = 0.002). IL-1RA (an inflammatory biomarker) decreased (−75%, p < 0.0125). LBM and bone mineral density were significantly lower and IGF-1 higher in the females at 1 year.

Conclusions

We found an association between neuromotor development and LBM suggesting that motor activity may influence LBM. Our particular intervention was ineffective. Whether activities provided largely by caregivers to enhance motor activity in prematurely born infants can affect the interrelated (1) balance of growth and inflammation mediators, (2) neuromotor development, (3) sexual dimorphism, and/or (4) body composition early in life remains unknown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Project BEGIN (Body Composition, Exercise, and Growth in Preterm Newborns) was designed to (1) fill gaps in our understanding of the relationship between body composition, neuromotor development, and sex in infants born prematurely during the first year of life and (2) determine whether these relationships could be altered by a parent/caregiver administered program to increase motor and physical activity in these infants. We hypothesized that in prematurely born infants during the first year of life following discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (1) neuromotor development would be correlated to body composition; (2) these interactions would be influenced by sex; and (3) a caregiver-administered intervention to increase motor activity would lead to more rapid increases in the development of fat free mass and neuromotor responsiveness. Although there is some evidence that physical activity interventions early in life can benefit body composition,1 the effect of the energy-expenditure side of energy balance (namely, motor or physical activity) on neuromotor development remains inadequately understood.

Extreme, moderate, and late premature birth are associated with adverse effects across the life span, in particular impairment in neuromotor function.2 Remarkable progress has been made over the past several decades in improving the NICU care of prematurely born infants. Far less is known about how to optimize neuromotor development in these infants following NICU discharge, and the transition from NICU to home can be profoundly challenging for the caregivers.3 Both body composition and neuromotor performance rapidly evolve (and often in an abnormal manner) early in the lives of prematurely born children. Consequently, physical rehabilitative interventions administered by caregivers following NICU discharge are compelling, minimally invasive, and potentially modifiable approaches for mitigating long-term health consequences of prematurity.4

Neuromotor performance and body composition components [i.e., lean body mass (LBM), bone mineral content and density (BMC and BMD, respectively), and fat mass (FM)] are linked across the life span both in young children5 and adults,6 and in studies performed in animal models, increasing motor activity in the immediate postnatal period led to increased muscle mass later in life.7 Circulating osteocalcin is an early indicator of bone mass development in preterm infants.8 The development of LBM is mediated by growth factors like insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and inhibited by inflammatory mediators.9 The clinical relevance of IGF-1 in particular is highlighted by its therapeutic use in preterm infants to attenuate retinopathy of prematurity and bronchopulmonary dysplasia.10

Consequently, we measured IGF-1 and osteocalcin and, as indicators of inflammation, interleukin-6 (IL-6)11 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA). IL-1RA is elevated in inflammatory states, and there is mounting preclinical data indicating that therapeutic IL-1 antagonism may reduce inflammation-induced injury in prematurity.12 Equally important are data highlighting the need to address sexual dimorphism. For example, sex-associated differences in motor performance can be observed in children as young as 3 years13 and in neuromotor function in adolescents exposed prenatally or in early childhood to environmental toxins.14

Methods

Study overview

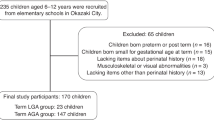

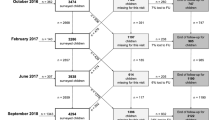

The overall study strategy is shown in Fig. 1. Prematurely born infants were randomly assigned to either (1) a parent/caregiver-implemented assisted-exercise and enhanced social interaction program (E) or (2) an enhanced social interaction alone comparison group (C). At NICU discharge and 1 year following discharge, enrolled infants were studied for body composition [by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)], circulating mediators of growth and inflammation, and neurodevelopment by the progression of standardized tests [Test of Infant Motor Performance (TIMP), which was specifically designed to test neuromotor performance in the first months of postnatal life15]. The TIMP was performed at hospital discharge and again at 3 months corrected age, and the Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS)—an observational assessment scale constructed to measure gross motor maturation in infants from birth through independent walking16—was performed at 3 months and 1 year corrected age.

Both the assisted-exercise and comparison groups received structured social interaction approaches developed by Spittle and colleagues.17 Social interaction activities were designed to enhance the engagement of caregivers with their infants through singing, speaking, and storytelling, activities which have been shown to improve postnatal development in prematurely born newborns.4 We purposefully chose to provide the social interaction instruction to the comparison group, rather than randomize to a more traditional “routine care” control group because we reached the conclusion that it would be ethically appropriate to offer potentially beneficial programs to both groups. This study was approved by the UCI Institutional Review Board.

Target population

The target population for this study was relatively healthy developing preterm infants nearing discharge from the NICU and their primary care givers (most likely a parent). Infants were enrolled from NICUs in our region, predominantly, UCI, Children’s Hospital of Orange County, and Miller Children’s Hospital. These institutions are part of the regional Clinical Trials Ecosystem, a collaboration sponsored by the UCI Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (ICTS). The study population consisted of all preterm infant–caregiver dyads who meet the inclusion criteria (see Table 1). We also relied on the attending neonatologist’s general impression of whether the infant–caregiver dyad would be likely to complete the study if enrolled.

Instruction for caregivers

Caregivers were taught to perform guided infant exercises by specially trained occupational and physical therapists and shown how to differentiate between appropriate and unsafe handling of infants during the exercises. Training occurred predominantly in the 2 weeks prior to discharge. The families were visited in the home 2 weeks post discharge and the training personnel determined the necessary number of sessions for an individual caregiver/infant dyad based on the trainer’s assessment of how well the caregiver understood and implemented the exercises and how the infants responded. Each parent/caregiver received about 40 min of instruction. No formal assessment of parent/caregiver skill was undertaken. Additional training of the parent/caregiver occurred at the participants’ home at 3, 6, and 9 months. As the infants grew and motorically progressed, the intervention protocol was adapted to include exercises neurodevelopmentally appropriate for the infants’ abilities.

Caregivers were asked to conduct the exercises for at least 15–20 min every day for 1 year. The exercise activities in the intervention group were based in part on the principles of Neurodevelopmental Treatment (NDT).18 NDT-based interventions have been successful in improving gross motor performance in a group of high-risk preterm infants in the NICU19 and in group of 4–12-month-old infants receiving therapy for posture and movement dysfunction.20 We modified the NDT-based activities every 2 months to address anticipated changes in motor performance over the first year of life. At each home visit, the exercises were observed by a physical or occupational therapist and parents were provided direction and training in the new exercises to use for the following 3-month period. In addition, caregivers were provided with a printed, updated list of exercises, which many placed in a prominent place (like a refrigerator) to remind them of the daily regimen. Study staff contacted each family 2–3 times per month to touch base and field questions and concerns.

Body composition

Standardized measures of length and weight were made at discharge and at 1 year of age. The change in LBM from discharge to 1 year was the primary outcome. LBM was measured using DXA in the ICTS core facility. DXA has been increasingly used for these assessments in children and in infants and preterm infants.21 DXA scans were done in unanesthetized participants using a whole-body fan-beam scanner (Hologic QDR Discovery-A Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA). Large-scale studies of DXA repeatability in infants are challenging; however, Shepherd and coworkers22 reported 18 repeated studies from 9 full term infants and found relatively low coefficients of variation in LBM (2.2%) and fat mass (8.4%). To optimize DXA comparability, the studies were scheduled to coincide with each infant’s pattern of napping, and all scans were performed while the infants slept. In addition, all participants were scanned in the same research-dedicated scanner guided by the same single technician (who had substantial experience in working with infants).

Circulating mediators of growth and inflammation

IGF-1, osteocalcin, IL-6, and IL-1RA were measured with high-precision enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using standard techniques at discharge and repeated at the end of the 1-year study period (EOS).

Neuromotor assessment

Because the period of birth to 1 year of age is developmentally dynamic, no single test can be used to assess the change in neuromotor status. We assessed the gross motor function changes that occurred over the first year of life using the TIMP at discharge from the NICU and at 3 months post discharge. AIMS was administered at 3 months post discharge and again at 1 year of life. This approach has been validated by a number of studies.16

Statistical analysis

The original study sample size calculations were performed for a range of possible magnitude differences in body composition outcomes in the initial study protocol submitted to the National Institutes of Health. According to those analyses, the required sample size to detect differences with a minimum of 80% power was determined to be 40 for effects of ≥1.0, 70 for effect size = 0.70, 120 for effect sizes of 0.55, and 140 for effect size = 0.44.

Chi-square analyses and t tests were performed to evaluate differences between (1) the randomized groups and (2) completers vs. non-completers on key baseline variables including sex, gestational age, and birth weight. For each primary outcome (AIMS z-score, TIMP z-score, DXA measures, and serum growth and inflammation factor measures) repeated-measures mixed-models analysis were used to evaluate the effect of intervention, time, and time × intervention interaction. Main effect of sex, sex × time interactions, and sex × intervention interactions were also evaluated. The mixed-models analyses satisfy intent-to-treat conditions in that all subjects and available data were utilized in calculation of estimated effects (regardless of completion status). Sensitivity analyses were performed restricting analyses to completers. In addition, change scores were calculated and Pearson correlations were performed to determine inter-relationship between the neuromotor assessments and level of change in DXA and growth and inflammation factor measures across the study period.

Results

Participant randomization and retention

A total of 163 infants were enrolled equally divided by sex and randomization to the E and C groups. In all, 99 (61%) completed all required assessments at EOS consisting of 24 females and 27 males in the comparison group and 22 females and 26 males in the assisted-exercise group (NS). Among the participants who did not complete the study but were willing to inform us of their discontinuation, the most common explanation was that the study burden (need to keep track of interaction with their infants and/or to perform the prescribed exercises) was too great in the context of busy family life. There were no significant differences between the assisted-exercise and comparison groups in terms of mean gestational age (E, 27 weeks; C, 27 weeks) or birth weight (E, 933 g; C, 930 g). Small-for-gestational age infants (SGA) comprised 9% of the E group infants and 13% of the C group infants (NS). In addition, participants lost to follow-up did not statistically differ from those completing the 12-month visit on these baseline factors (Fig. 2).

Body composition

As expected, body weight increased over the 1-year period of study. No differences were observed between the intervention and comparison groups. There were significant increases in almost all DXA-measured indices of body composition (Table 2). There was no effect of the assisted motor activity intervention on the DXA results (Figs. 3 and 4). No substantial effects of SGA status on growth parameters were noted, but only 11% of the enrolled infants were SGA. Gestational age was not correlated with the degree of change in DXA or growth factor measures.

Circulating mediators of growth and inflammation

As shown in Table 3, there were significant changes in IGF-1, IL-1RA, and osteocalcin over the 1-year period of observation. IGF-I significantly increased, and both IL-1RA and osteocalcin decreased. IL-6 did not change. We found no effect of the exercise intervention. As shown in Fig. 5, the change in IGF-1 was correlated to the change in LBM over the course of the study (all participants). We also found significant relationships between metrics of body fat and circulating predictive biomarkers [n.b., we used the Food and Drug Administration Biomarkers, Endpoints, and other Tools criteria23] related to inflammation suggesting that the greater the degree of inflammation, the smaller the accrual of body fat over the course of the study (Table 4). Finally, we found a significant inverse correlation between the change in IL-1RA and IGF-1 (r = −0.31, p = 0.0087).

Neurodevelopment

We found small but unexpected changes in the TIMP and AIMS assessments of neurodevelopment (Table 5). Gestational age (birth week) was positively correlated with the TIMP scores at 3 months (r = 0.3172, p = 0.002) as well as the degree of TIMP change between 0 and 3 months (r = 0.21, p = 0.039). SGA status was also correlated with the degree of TIMP change. Those in the SGA group exhibited larger decrease in TIMP z-score across the 3 months compared to the non-SGA group (mean change SGA was −1.15; mean change non-SGA was −0.522, p = 0.034). No additional effect of SGA status on TIMP or AIMS was observed.

Relationship between body composition and neurodevelopment

We found significant correlations between the AIMS assessment of neuromotor function and LBM determined by DXA over the course of the study (Table 6 and Fig. 6).

Sex differences

As shown in Table 7, we found a number of sexual dimorphisms over the course of the study.

Discussion

Gauging the effect of physical and motor activity on the development of body composition in premature infants is challenging due to factors such as achieving an adequate study sample size, distinguishing specific effects of motor activity on body composition when rapid changes in growth and growth mediators are occurring naturally, and the limited methodologies capable of precise measurements of muscle, fat, and bone. The longitudinal data that we observed over a roughly 1-year period in a cohort of prematurely born infants provide novel insights into the patterns of body composition growth in this at-risk population. Sexual dimorphisms were observed in key metrics, thus sex must be accounted for in studies of growth and development from very early in life. We did not demonstrate that our specific caregiver-implemented exercise intervention altered the trajectory of growth and development, perhaps because we underestimated the degree of training and support necessary for a caregiver-administered program to succeed. Nonetheless, we speculate that the association between LBM and neuromotor assessment over the study duration suggests that levels of physical and motor activity may play a role in the broader development of body composition.

An intriguing observation from the study was that neuromotor assessment at the end of the study was significantly correlated with DXA measures of LBM (Table 6 and Fig. 6), in support of a key study hypothesis. The TIMP and AIMS rely on the baby’s motor response to various external stimuli and scale functional capacities and the quality of movement. Muscle function and size, in turn, depend in large measure on the repetitive use of the nerves and muscles involved in physical activity. This is the basis of the training effect known to occur later in life, but the connection between muscle utilization and muscle size and function can be observed early in life as well. Brachial plexus injury at birth leads to reduced muscle mass in the first year of life.24 Our earlier study in postnatal rats cited above showed that increasing motor activity in the immediate postnatal period could lead to increased muscle mass later in life.7 We speculate that higher levels of motor activity in some infants (for whatever reasons, environmental or innate behavior) were ultimately reflected in both better standardized tests of neuromotor function and increased LBM.

An additional major goal of the study was to determine whether growth and neuromotor trajectories in prematurely born infants could be influenced by a caregiver-implemented intervention designed to increase physical and motor activity. The intervention appeared to have no effect on DXA measures of body composition or on neuromotor function. A few previous studies conducted before discharge from the NICU have shown that a variety of interventions involving assisted exercise (recently reviewed by Eliakim et al.25) and massage (recently reviewed by Álvarez et al.26) may positively influence growth indices and hospital stay. These previous studies were short term in duration and the intervention was conducted by trained personnel in the NICU.

In contrast, our study attempted to train caregivers/parents to provide assisted exercise in the participants’ homes. A major limitation of this approach was the difficulty in quantifying the exercise “dose,” the actual amount of interaction time between the caregiver and the baby, amount of increased physical and motor activity, and performance that resulted from the interaction. While we did visit the participants’ home every 3 months to teach the parents developmentally appropriate exercises and attempted to contact the care providers up to three times on the months that they were not visited, we recognize that these are not optimal metrics of dose fidelity. Studies designed to improve neuromotor development in premature infants in the post NICU discharge period have been successful, but have also demonstrated that the beneficial effects of regular neuromotor and physical activity can disappear upon cessation of active intervention and supervision by trained professionals.27 It is possible that we underestimated the amount of training and support needed by often-busy and stressed caregivers28 to consistently administer a motor activity program capable of altering neurodevelopment and/or body composition. This burden may have contributed to the 39% dropout rate we observed over the course of the year-long observation period.

There was a small but significant reduction in the TIMP z-score between baseline and 3 months. The AIMS z-scores were lower at 3 months and remained lower at EOS (Table 5). Emerging data in premature infants suggests that sustained improvement in neuromotor function depends on continuous, regular intervention by caregivers or providers.19 One possible explanation for our data is that, despite our efforts, the level of direct intervention to enhance neuromotor function in premature infants in our region remains suboptimal. Although the SGA infants demonstrated reduced TIMP over the first 3 months after discharge, we observed no further effect of SGA on the AIMS at EOS.

We gained insight into some possible biological mechanisms that play a role in the control of body composition early in life in prematurely born infants. IGF-1 increased substantially in our cohort, and there was a positive correlation between the increase in IGF-1 and the increase in LBM over the study duration (Fig. 5). Circulating levels of IGF-1 and its related binding proteins are associated with muscle mass, exercise training, and disuse across the life span.29,30 An inverse correlation between IGF-1 and circulating indicators of inflammation have been observed early in postnatal life in prematurity.9,11 In the present study, we noted increases in IGF-1 and decreases in IL-1RA (as well as a significant inverse correlation) suggesting that the inverse relationship between growth factors and inflammation can be observed during the first year of postnatal life in infants born prematurely.

In recent years, the observation of increased rates of obesity later in life in infants born prematurely (whether SGA or appropriate weight for gestational age) has formed the hypothesis that abnormal “catch-up fat” accumulation in early postnatal life may play a role.31 A novel observation from our study was the inverse correlation between body fat accumulation and circulating indicators of inflammation (Table 4). Murine models show that IL-6 inhibits growth in postnatal life.32 In adults, circulating IL-6 is associated with sarcopenia and cachexia,33 and IL-6 stimulates lipolysis in adipocytes,34 indicating, possibly, a direct inhibitory effect of inflammatory mediators on fat tissue accumulation in postnatal life. Our data suggest that the balance between growth factors and antagonistic proinflammatory mediators influence fat and lean tissue accumulation early in life in prematurely born infants.

We found a significant decrease in osteocalcin over the study period. This was observed despite the increase in BMD and BMC. Osteocalcin is higher in children compared to adults, peaking in both boys and girls at the age of the pubertal growth spurt.35,36 The decline in osteocalcin suggests that serum levels may reflect growth velocity rather than growth in absolute terms. Data from premature infants reveals that linear growth velocity is as high as 1.4–1.6 cm/week at 30–34 weeks post gestational age and declines to about 0.7 cm/week at 50 weeks post gestational.37,38 Most likely, bone growth and mineralization continued over the duration of the study, but the declining rate of bone growth was reflected by the declining osteocalcin levels.

Little is known regarding sexual dimorphism in growth and development in the first year of postnatal life in infants born prematurely. We found evidence for sex effects in body composition and growth mediators. BMD was lower at EOS in the females. Reduced peak bone mass has been observed in the third decade of life of individuals with a history of premature birth and low birth weight, but no sex differences were observed.39 We also found greater lean body mass at EOS in the male infants. Fields et al.40 noted greater lean tissue in full term male compared with female infants at 1 month of age, estimated using whole-body plethysmography. In the Fields’ study, sex differences disappeared by 6 months of age, leading the authors to conjecture that the lean mass differences paralleled the higher levels of androgen levels at birth in male infants, which dissipates roughly by 6 months. Despite the lower LBM levels in the females at EOS, their IGF-1 circulating levels were higher.

Conclusion

This study reports potentially useful information about changes in body composition and associated circulating growth biomarkers over the first year of life following NICU discharge in infants born prematurely. Our attempts to increase muscle mass and neuromotor development through a parent-provided assisted-exercise intervention was, however, not successful. We found a significant association between indices of neuromotor development and body composition, but whether increased neuromotor development and/or motor activity stimulated LBM growth or vice versa could not be determined from our data. These observations form the basis for studies that can optimize the enhanced physical activity “dose” over the long term and provides insights/considerations for how to support parent compliance for busy caregivers and families of prematurely born infants.

References

Eliakim, A., Litmanovitz, I. & Nemet, D. The role of exercise in prevention and treatment of osteopenia of prematurity: an update. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 29, 450–455 (2017).

Stewart, D. L. & Barfield, W. D. Updates on an at-risk population: late-preterm and early-term infants. Pediatrics 144, e20192760 (2019).

Premji, S. S. et al. A qualitative study: mothers of late preterm infants relate their experiences of community-based care. PLoS ONE 12, e0174419 (2017).

Spittle, A., Orton, J., Anderson, P. J., Boyd, R. & Doyle, L. W. Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD005495 (2015)

Kakebeeke, T. H. et al. Association between body composition and motor performance in preschool children. Obes. Facts 10, 420–431 (2017).

Gianoudis, J., Bailey, C. A. & Daly, R. M. Associations between sedentary behaviour and body composition, muscle function and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. Osteoporos. Int. 26, 571–579 (2015).

Buchowicz, B. et al. Increased rat neonatal activity influences adult cytokine levels and relative muscle mass. Pediatr. Res. 68, 399–404 (2010).

Czech-Kowalska, J. et al. The clinical and biochemical predictors of bone mass in preterm infants. PLoS ONE [Internet] 11, e0165727 (2016).

Ahmad, I. et al. Inflammatory and growth mediators in growing preterm infants. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 20, 387–396 (2007).

Ley, D. et al. rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 in preterm infants: a phase 2 randomized controlled trial. J. Pediatr. 206, 56.e8–65.e8 (2019).

Hellgren, G. et al. Increased postnatal concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines are associated with reduced IGF-I levels and retinopathy of prematurity. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 39, 19–24 (2018).

Royce, S. G. et al. Airway remodeling and hyperreactivity in a model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and their modulation by IL-1 receptor antagonist. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 55, 858–868 (2016).

Kakebeeke, T. H. et al. Neuromotor development in children. Part 4: New norms from 3 to 18 years. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 60, 810–819 (2018).

Chiu, Y.-H. M. et al. Sex differences in sensitivity to prenatal and early childhood manganese exposure on neuromotor function in adolescents. Environ. Res. 159, 458–465 (2017).

Peyton, C., Schreiber, M. D. & Msall, M. E. The Test of Infant Motor Performance at 3 months predicts language, cognitive, and motor outcomes in infants born preterm at 2 years of age. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 60, 1239–1243 (2018).

Song, Y. H. et al. The validity of two neuromotor assessments for predicting motor performance at 12 months in preterm infants. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 42, 296 (2018).

Spittle, A. J. et al. Preventive care at home for very preterm infants improves infant and caregiver outcomes at 2 years. Pediatrics 126, e171–e178 (2010).

Howle, J. M. Neuro-Developmental Treatmant Approach: Theoretical Foundations and Principles of Clinical Practice (Neuro-Developmental Treatment Association, Laguna Beach, CA, 2003).

Ustad, T. et al. Early parent-administered physical therapy for preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 138, e20160271 (2016).

Arndt, S. W., Chandler, L. S., Sweeney, J. K., Sharkey, M. A. & McElroy, J. J. Effects of a neurodevelopmental treatment-based trunk protocol for infants with posture and movement dysfunction. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 20, 11–22 (2008).

Tremblay, G. et al. Body composition in very preterm infants: role of neonatal characteristics and nutrition in achieving growth similar to term infants. Neonatology 111, 214–221 (2017).

Shepherd, J. A. et al. Advanced analysis techniques improve infant bone and body composition measures by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. J. Pediatr. 181, 248.e3–253.e3 (2017).

FDA-NIH Biomarker Working Group. BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools) Resource (Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD and National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (joint sponsors), 2016).

Zaidman, C. M., Holland, M. R., Noetzel, M. J., Park, T. S. & Pestronk, A. Newborn brachial plexus palsy: evaluation of severity using quantitative ultrasound of muscle. Muscle Nerve 47, 246–254 (2013).

Eliakim, A., Litmanovitz, I. & Nemet, D. The role of exercise in prevention and treatment of osteopenia of prematurity: an update. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 29, 450–455 (2017).

Álvarez, M. J. et al. The effects of massage therapy in hospitalized preterm neonates: a systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 69, 119–136 (2017).

Oberg, G. K. et al. Effects at 3 months corrected age of a parent-administered exercise program in the neonatal intensive care unit: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Phys. Ther. J. (2020, in press).

McGowan, E. C. et al. Maternal mental health and neonatal intensive care unit discharge readiness in mothers of preterm infants. J. Pediatr. 184, 68–74 (2017).

Bucci, L. et al. Circulating levels of adipokines and IGF-1 are associated with skeletal muscle strength of young and old healthy subjects. Biogerontology 14, 261–272 (2013).

Eliakim, A., Scheett, T. P., Newcomb, R., Mohan, S. & Cooper, D. M. Fitness, training, and the growth hormone→insulin-like growth factor I axis in prepubertal girls. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 2797–2802 (2001).

Okada, T. et al. Early postnatal alteration of body composition in preterm and small-for-gestational-age infants: implications of catch-up fat. Pediatr. Res. 77, 136–142 (2015).

Denson, L. et al. Early elevation in interleukin-6 is associated with reduced growth in extremely low birth weight infants. Am. J. Perinatol. 34, 240–247 (2016).

Li, C. et al. Circulating factors associated with sarcopenia during ageing and after intensive lifestyle intervention. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 10, 586–600 (2019).

Yang, Y., Ju, D., Zhang, M. & Yang, G. Interleukin-6 stimulates lipolysis in porcine adipocytes. Endocrine. 33, 261–269 (2008).

Cole, D. E., Carpenter, T. O. & Gundberg, C. M. Serum osteocalcin concentrations in children with metabolic bone disease. J. Pediatr. 106, 770–776 (1985).

Tarallo, P., Henny, J., Fournier, B. & Siest, G. Plasma osteocalcin: biological variations and reference limits. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 50, 649–655 (1990).

Villar, J. et al. Postnatal growth standards for preterm infants: the Preterm Postnatal Follow-up Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet Glob. Health 3, e681–e691 (2015).

Fenton, T. R. et al. An attempt to standardize the calculation of growth velocity of preterm infants-evaluation of practical bedside methods. J. Pediatr. 196, 77–83 (2018).

Balasuriya, C. N. D. et al. Peak bone mass and bone microarchitecture in adults born with low birth weight preterm or at term: a cohort study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 102, 2491–2500 (2017).

Fields, D. A., Krishnan, S. & Wisniewski, A. B. Sex differences in body composition early in life. Gend. Med. 6, 369–375 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Julia Rich for her dedication to the enrollees in her capacity as clinical study coordinator. This study was financially supported by NIH NHLBI R01HL110163, NCATS UL1 TR001414, and The NIH Office of Women’s Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.C., G.L.G., S.R.-A., N.D., C.T.L., and B.K. conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. F.H. and F.Z. supervised biomarker mediator laboratory analysis and reviewed and revised the manuscript. A.S. was responsible for the statistical design and analysis. I.A. and A.S. coordinated study participant selection and recruitment and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.L.G. is a co-author of the TIMP and a partner in Infant Motor Performance Scales, LLC, publisher of the TIMP. The other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, D.M., Girolami, G.L., Kepes, B. et al. Body composition and neuromotor development in the year after NICU discharge in premature infants. Pediatr Res 88, 459–465 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-0756-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-0756-2