Abstract

Introduction

Congenital chloride diarrhea (CLD) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by watery diarrhea with a high level of fecal Cl−, metabolic alkalosis, and electrolyte alterations. Several intestinal and extraintestinal complications and even death can occur. An optimal knowledge of the clinical features and best therapeutic strategies is mandatory for an effective management.

Methods

Articles published between 1 January 1965 and 31 December 2019, reported in PUBMED and EMBASE, were evaluated for a systematic review analyzing four categories: anamnestic features, clinical features, management, and follow-up strategies.

Results

Fifty-seven papers reporting information on 193 CLD patients were included. The most common anamnestic features were positive family anamnesis for chronic diarrhea (44.4%), consanguinity (75%), polyhydramnios (98.3%), preterm delivery (78.6%), and failure to pass meconium (60.7%). Mean age at diarrhea onset was 6.63 days. Median diagnostic delay was 60 days. Prenatal diagnosis, based on molecular analysis, was described in 40/172 (23.3%). All patients received NaCl/KCl-substitutive therapy. An improvement of diarrhea during adulthood was reported in 91.3% of cases. Failure to thrive (21.6%) and chronic kidney disease (17.7%) were the most common complications.

Conclusions

This analysis of a large population suggests the necessity of better strategies for the management of CLD. A close follow-up and a multidisciplinary approach is mandatory to manage this condition characterized by heterogeneous and multisystemic complications.

Impact

-

In this systematic review, we describe data regarding anamnestic features, clinical features, management, and follow-up of CLD patients obtained from the largest population of patients ever described to date.

-

The results of our investigation could provide useful insights for the diagnostic approach and the management of this condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital chloride diarrhea (CLD) is an autosomal recessive disease characterized by lifelong watery diarrhea of prenatal onset with high fecal Cl− concentration caused by mutations in solute carrier family 26, Member 3 (SLC26A3) gene that encodes for the Cl−/HCO3− exchanger.1 The absence of SLC26A3 results in an acidification of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract fluids and in a reduction of fluid absorption that leads to a high volume of watery diarrhea with a Cl− content >90 mM and development of metabolic alkalosis with secondary hyper-reninemic hyperaldosteronism.2,3 The SLC26A3 is expressed in many parts of the human body and this could lead to the occurrence of many extraintestinal complications, especially when it remains untreated and undiagnosed for a long time.1

The incidence of CLD seems to be underestimated. While most cases arise from countries where there is a high rate of consanguinity (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait) or where there are high rates of carriers of the same mutation due to founder effect (Finland, Poland, and Japan), single cases could appear worldwide.4,5,6 Abnormal fluid transport may begin in utero manifesting with polyhydramnios and bowel dilatation.7 Then, soon after birth, patients usually present with severe diarrhea that typically, within a few days, leads to severe dehydration and serum electrolyte imbalance. In the vast majority of cases, patients require hospitalization and prompt rehydration.8 For all these reasons, an optimal knowledge of all CLD clinical features and best therapeutic strategies is mandatory for an effective management of these patients. We conducted a systemic review on these aspects, and reported data on CLD patients described so far.

Methods

Data source

We conducted a systematic review in PUBMED and EMBASE using the following keywords: congenital chloride diarrhea, congenital chloride-losing diarrhea, congenital chloridorrhea, congenital diarrheal disorders, intractable diarrhea, neonatal onset diarrhea, and SLC26A3.

All articles published between 1 January 1965 and 31 December 2019 were included without linguistic or geographical restriction.

We searched for papers describing CLD patients’ features; we excluded review articles. The inclusion criteria included patient’s description with a sure CLD diagnosis based on fecal Cl− >90 mmol/L and fecal cationic gap F-Na+ + K+ < Cl– and/or mutations of SLC26A3 gene.2

Cases from all included studies were evaluated and analyzed.

Data extraction, evaluation, and synthesis

Study selection followed PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). A total of 229 papers were evaluated. Three researchers independently judged the study eligibility. Data extraction from individual studies was performed in triplicate. All potential differences in data extraction were discussed between authors, and resolved. After reading titles, abstracts, and eliminating duplicates, 57 papers were selected and assessed by the authors.

Data extraction

We analyzed each of the retained studies to create our own database.

Four different categories were analyzed:

-

1.

The first included familial anamnestic features: the presence of consanguinity, positive familiar anamnesis for chronic diarrhea, prenatal ultrasound (US) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, gestational age at delivery, mode of delivery, birth weight, presence of abdominal distention, failure to pass meconium, and any additional perinatal/neonatal problem.

-

2.

The second category described clinical features of CLD patients: stool pattern, fecal electrolytes, serum Na+, K+, Cl−, pH, HCO3−, renin, and aldosterone levels.

-

3.

The third category described the CLD management: hospitalizations before diagnosis, referral diagnosis, age at CLD diagnosis, time between diarrhea onset and definitive CLD diagnosis, diagnostic tests, and therapeutic approaches adopted.

-

4.

The fourth category described the follow-up data: compliance to therapy, length of follow-up, change in the stool pattern, body growth, and the occurrence of complications.

Data collection and analysis

In each included paper, we evaluated all categories and variables. For each variable, we reported the total of cases in which that variable was available; when a variable was not described, it was considered as “not valuable”.

All data were collected in a dedicated database and analyzed by a statistician using SAS® for Windows release 9.4 (64-bit) or later (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) or SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc., version 23.0, Chicago, IL). Categorical data were presented with numbers and percentages, and continuous data were reported as mean/median and range, according to the statistical distribution.

Results

Fifty-seven papers reporting a total of 193 cases were included in the study.6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64 The main anamnestic features of CLD patients are depicted in Table 1. Consanguinity and positive family anamnesis for chronic diarrhea were observed in >40% of cases; in particular, in nine cases, a family history of fatal neonatal onset chronic diarrhea was reported,30,32,41,43,49,61 and in one of them, CLD was diagnosed postmortem.11 Prenatal evidence of bowel-loop dilatation and polyhydramnios was demonstrated in 69/84 (82.1%) and in 118/120 (98.3%) of cases at 29 weeks of gestation (ranged from 22 to 35) and at 30 weeks of gestation (ranged from 22 to 38), respectively, by the results of US and/or MRI.11,14,45,47,50

Prematurity and low birth weight were observed in the majority of cases. Failure to pass meconium was observed in 68/112 (60.7%) of the cases, and 122/145 (82.7%) presented abdominal distention at birth. Explorative laparotomy was performed in 12 cases,6,13,15,22,31,32,34,64 but in only 4 cases, they found obstruction due to malrotation13,15 or volvulus.32 Additional perinatal problems included meconium-stained amniotic fluid,10,58 atrio-ventricular septal defect,12 perinatal sepsis,13,22,64 lip and cleft palate,41 jaundice,41,42,43,64 inguinal hernia,43 deafness,43,62 transient tachypnea,47 respiratory distress syndrome,52,64 bilateral hydroceles,54 convulsion,64 and pregnancy complicated by chorioamnionitis.57

Regarding clinical features, the age at diarrhea onset was described in 108 patients, the median was 1 day (mean 6.63 days, ranged 1–90 days). Stool pattern prior to the start of therapy was described in 181 patients and was characterized by a median of 5.6 (mean 5.9, ranged 2–17) watery bowel movements/day. The abnormal Na+, K+, and Cl− serum level at diagnosis was reported in 99/113 (87.6%), 101/115 (87.8%), and 77/115 (66.9%) of cases, respectively. The abnormal serum renin and aldosterone levels at diagnosis were observed in 86/86 (100%) and metabolic alkalosis in >95% of cases (93/96).

Regarding the features of CLD management, the number of hospitalizations before diagnosis was described in 23 CLD patients with a median of 3 hospitalizations (mean 3.6). CLD was the referral diagnosis in 123/165 (74.6%) cases, whereas diarrhea of unknown origin, cystic fibrosis, Bartter’s syndrome, and food allergy were the referral diagnoses in 21/165 (12.7%), 1/165 (0.6%), 18/165 (11%), and 2/165 (1.2%), respectively. Median age at diagnosis was 60 days (mean 426.79 days, ranged from in utero diagnosis to 12 years). In 40/172 (23.3%), the diagnosis was obtained in utero (based on invasive molecular analysis), in 56/172 (32.5%) during the first 30 days of life, in 39/172 (22.7%) between 30 days and 6 months, and in 37/172 (21.5%) after the sixth month of age. Data from 172 patients revealed a median time between diarrhea onset and definitive CLD diagnosis of 60 days (mean 419 days, ranged from 2 days to 12 years). Molecular diagnosis was described in 102/193 cases. In Table 2, the genotypes reported are described. All patients received NaCl/KCl-based substitutive therapy, whereas in 51 patients, additional therapies were adopted (Table 3). At the time of diagnosis, failure to thrive was observed in 27/125 (21.6%) of cases, whereas psychomotor delay alone was appraised in 11/125 (8.8%) or in combination with failure to thrive in 5/125 (4%).

The median length of follow-up was 9 years (mean 11.15 years), and a good compliance to NaCl/KCl supplementation was reported in 137/150 (91.3%) cases.

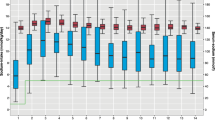

The main clinical features observed during the follow-up, after the start of therapy, are given in Table 4. Serum electrolyte balance and diarrhea improvement were reported in 105/115 (91.3%) and 166/177 (93.7%) of cases, respectively. During follow-up and after the start of therapy, weight and length below the third percentile were apprised in 13/125 (10.4%), while psychomotor delay was reported in 8/125 (6.4%). Renal problems were reported in about 33/181 (17.7%) of cases;6,21,28,31,35,38,43,46,62,64 in 10/181 (5.5%), the necessity of dialysis or transplant was described.21,35,46,55,61,62

During the follow-up, the following conditions were reported: GI disorders (celiac disease,31 volvulus,33,57 soiling,62,64 Giardia lamblia infection,44 megacolon,6 intussusception,55 inguinal hernia,62,64 and inflammatory bowel diseases62), neurological problems (migraine,62 epilepsy62), psychiatric disorders (Asperger syndrome,51 tic disorder,6 dysgraphia,6 eating disorders,62 attention- deficit hyperactivity disorder,6 and anxiety6), genital disorders (infertility,62 spermatocele62), and renal disorders (Bartter syndrome,43 enuresis,6,62,64 and uremia62). Additionally, cases of endocarditis,21 growth hormone deficiency,6 hypertension,6,62 hyperuricemia,61,62,64 allergic diseases,62 gouty arthritis,62 mild hearing defect,62 and enamel defect62,64 have been reported.

In eight women, 15 uneventful pregnancy events were described.59,62 Two male CLD patients had offspring, one with in vitro fertilization (IVF).62

Discussion

CLD is a challenging condition because of the severity of the clinical picture and the broad range of disorders in differential diagnosis.8 Early diagnosis is essential for an effective management.44 In fact, if untreated, the CLD-associated metabolic imbalance together with severe dehydration is usually lethal during the first few months of life.

Diagnosis

As supported by our findings, the main “red flags” could be positive familiar anamnesis for consanguinity and severe early-onset chronic diarrhea with prenatal evidence of dilated bowel loops even at the end of the second trimester, polyhydramnios, prematurity, and low birth weight. Up to 100% of CLD presented with ≥1 of such features, and 95% presented with ≥2. Altogether, the presence of such features should strongly suggest the necessity of a careful diagnostic workup and genotyping. Molecular analysis is an efficient diagnostic tool and should be considered as a means of early diagnosis of CLD, especially when the clinical diagnosis remains uncertain, and should be expanded to close relatives.65,66,67

A multigene next-generation sequencing panel to evaluate congenital diarrheal disorder-related genes is the best option and, in the case of novel mutation, should be supplemented by phylogenic studies and functional analysis.66

The knowledge of this disease has improved during the years; before 2000, the median diagnostic delay was of 309 days; from 2000 to nowadays, it is of 60 days. However, from our subanalysis, in high CLD-prevalence countries (Saudi Arabia, Poland, Japan, Korea, Finland, and Kuwait), the median diagnostic delay is 60 days; in the rest of the world, the disease is still misdiagnosed with a median diagnostic delay of 217 days.

A CLD case could be observed everywhere in the world. Our data further confirm the importance of better CLD knowledge among gynecologists, neonatologists, pediatricians, gastroenterologists, and nephrologists. Early-onset watery diarrhea with fecal Cl– content >90 mM, together with the previously reported anamnestic and perinatal features, should drive a fast and careful diagnostic workup including the genotyping. However, as suggested also by others,28,40,47 it could be preferable to repeat the measurement of the Cl− fecal level in patients with a strong suspect of CLD but with an unexpected low Cl− fecal level due to severe dehydration. In such cases, it could be preferable to repeat the measurement of fecal Cl− soon after the resolution of dehydration.

Management

Soon after diagnosis, life-saving NaCl/KCl salt-substitution therapy is able to protect the patient from dehydration, hypoelectrolytemia with activation of the renin–aldosterone system, and from other frequent complications of untreated CLD observed in our study, such as failure to thrive, chronic kidney disease, and psychomotor delay.68

Several additional treatments have been described in CLD patients, with butyrate and cholestyramine resulted effective in reducing the diarrhea severity in the majority of cases.

Butyrate may act efficiently on either fecal ion loss, or on the severity of diarrhea in CLD patients through the stimulation of Na+/H+ exchangers 2 (NHE2) and 3 (NHE3) activity, and the inhibition of Na–K–2Cl cotransporter on enterocyte.34,51 In addition, it has been demonstrated in CLD patients that butyrate is able to modulate the expression of the two main intestinal Cl− transporters: the downregulation in adenoma exchanger (DRA) and the putative anion transporter 1 (PAT-1).34,51 It has been suggested that the cholestyramine efficacy in CLD patients may be due to its ability to bind bile acids that reach the colon with increased ileal effluent and stimulation of additional Cl− secretory response.2 More studies are advocated to better elucidate the mechanisms of action and the long-term efficacy of such compounds in CLD management.

Physicians should pay attention to supplementation therapy. Salt substitution should be administered based on age and body weight, and adjusted based on urine Cl−, serum electrolyte level, and acid–base status.68 CLD patients should always be up to date with vaccination to avoid infections that may cause life-threatening dehydration.68 Auxological parameters and neuropsychological development should be evaluated regularly. We found a high rate of neuropsychomotor disorders in CLD patients. The origin of such conditions is still poorly understood.

As reported by others,44 we did not observe any relevant genotype/phenotype relationship.

The poor compliance to therapy and the diagnostic delays were the two most important negative prognostic factors; in these patients, high rates of failure to thrive, psychomotor delay, and renal impairment have been apprised.

In adult patients, an important aspect in the CLD clinical management is not only adequate substitutive therapy but also monitoring and treating intestinal and extraintestinal complications such as chronic kidney disease, hyperuricemia, spermatoceles, and inflammatory bowel diseases.62,68 These conditions could derive from dysfunctional SLC26A3-mediated anion transport in the different tissues. In addition, the absence of SLC26A3 has been associated with higher expression of tumor necrosis factor-α in intestinal mucosa,69 and SLC26A3 has been described as a susceptibility locus for ulcerative colitis.70 This primary evidence should be investigated in order to define the risk of IBD in this population that is still unclear.

Of note, chronic kidney disease, derived mainly from chronic blood-volume restriction,68 requesting dialysis and/or renal transplant, was described in >5% of cases. This suggests the importance of a careful assessment of renal function during the follow-up of CLD patients performed by a gastroenterologist and a nephrologist.68 In addition, physicians should pay attention including on psychological disorders that may appear later in adulthood; they could compromise the ability and safety of self-administering NaCl/KCl71 (Fig. 2).

In conclusion, we provided information on a large number of CLD patients with heterogeneous genotypes observed in different countries. Previous reviews were based on a smaller number of patients and limited to a specific geographic area.1,62,63,64

The results of our investigation could provide useful insights for the diagnostic approach and the management of this condition from prenatal life to adulthood.

References

Holmberg, C., Perheentupa, J., Launiala, K. & Hallman, N. Congenital chloride diarrhoea. Clinical analysis of 21 Finnish patients. Arch. Dis. Child. 52, 255–267 (1977).

Holmberg, C. Congenital chloride diarrhoea. Clin. Gastroenterol. 15, 583–602 (1986).

Xia, W. et al. The distinct roles of anion transporters Slc26a3 (DRA) and Slc26a6 (PAT-1) in fluid and electrolyte absorption in the murine small intestine. Pflug. Arch. 466, 1541–1556 (2014).

Höglund, P. et al. Genetic background of congenital chloride diarrhea in high-incidence populations: Finland, Poland, and Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 760–768 (1998).

Shawoosh, H. A. et al. Congenital chloride diarrhea from the west coast of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 21, 207–208 (2000).

Konishi, K. I. et al. Genetics, and long-term outcome in congenital chloride diarrhea: a nationwide study in Japan. J. Pediatr. 214, 151–157 (2019).

Alzahrani, A. K. Congenital chloride losing diarrhea. Pediatr. Ther. 4, 193–198 (2014).

Berni Canani, R., Castaldo, G., Bacchetta, R., Martín, M. G. & Goulet, O. Congenital diarrhoeal disorders: advances in this evolving web of inherited enteropathies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 293–302 (2015).

Wedenoja, S., Holmberg, C. & Hoglund, P. Oral butyrate in treatment of congenital chloride diarrhea. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103, 252–254 (2008).

Kawamura, T. & Nishiguchi, T. Congenital Chloride Diarrhea (CCD): a case report of CCD suspected by prenatal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). SIQI Am. J. Case Rep. 18, 707–713 (2017).

Siqi, W. U. et al. Novel solute carrier family 26, member 3 mutation in a prenatal recurrent case with congenital chloride diarrhea. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 45, 2280–2283 (2019).

Ben-David, Y., Halevy, R., Sakran, W., Zehavi, Y. & Spiegel, R. The utility of next generation sequencing in the correct diagnosis of congenital hypochloremic hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 62, 103728–103731 (2019).

Dávid, E. et al. Genetic investigation confirmed the clinical phenotype of congenital chloride diarrhea in a Hungarian patient: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 19, 16–19 (2019).

Chouikh, T., Mottet, N., Lenoir, M. & Chaussy, Y. Bowel dilation diagnosed prenatally. J. Pediatr. 190, 284–284 (2017).

Gils, C., Eckhardt, M. C., Nielsen, P. E. & Nybo, M. Congenital chloride diarrhea: diagnosis by easy-accessible chloride measurement in feces. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2016, 2519498–2519500 (2016).

Azzabi, O. et al. SLC26A3 gene mutations in Tunisian patients with congenital chloride diarrhea. Tunis. Med. 94, 83–84 (2016).

Mustafa, O. M. & Al-Aali, W. Y. Honeycomb fetal abdomen: characteristic sign of congenital chloride diarrhea. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 48, 797–799 (2016).

Hirakawa, M., Hidaka, N., Kido, S., Fukushima, K. & Kato, K. Congenital chloride diarrhea: accurate prenatal diagnosis using Color Doppler sonography to show the passage of diarrhea. J. Ultrasound Med. 34, 2113–2115 (2015).

Reimold, F. R. et al. Congenital chloride-losing diarrhea in a Mexican child with the novel homozygous SLC26A3 mutation G393W. Front. Physiol. 6, 179–189 (2015).

Bin Islam, S. et al. Captopril in congenital chloride diarrhoea: a case study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 33, 214–219 (2015).

Abou Ziki, M. D. & Verjee, M. A. Rare mutation in the SLC26A3 transporter causes life-long diarrhoea with metabolic alkalosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 206849–206853 (2015).

Krzemień, G., Szmigielska, A., Jankowska, K. & Roszkowska-Blaim, M. Congenital chloride diarrhea mimicking meconium ileus in newborn. Med Wieku Rozwoj. 17, 320–323 (2013).

Saneian, H. & Bahraminia, E. Congenital chloride diarrhea misdiagnosed as pseudo-Bartter syndrome. J. Res. Med. Sci. 18, 822–824 (2013).

Seo, K. A. et al. Congenital chloride diarrhea in dizygotic twins. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 16, 195–199 (2013).

Shamaly, H., Jamalia, J., Omari, H., Shalev, S. & Elias, N. Congenital chloride diarrhea presenting in newborn as a rare cause of meconium ileus. J. Perinatol. 33, 154–156 (2013).

Lee, E. S., Cho, A. R. & Ki, C. S. Identification of SLC26A3 mutations in a Korean patient with congenital chloride diarrhea. Ann. Lab Med. 32, 312–315 (2012).

Eğrıtaş, O., Dalgiç, B. & Wedenoja, S. Congenital chloride diarrhea misdiagnosed as Bartter syndrome. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 22, 321–323 (2011).

Özbay Hoşnut, F., Karadağ Öncel, E., Öncel, M. Y. & Özcay, F. A Turkish case of congenital chloride diarrhea with SLC26A3 gene (c.2025_2026insATC) mutation: diagnostic pitfalls. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 21, 443–447 (2010).

Rodríguez-Herrera, A., Navas-López, V. M., Redondo-Nevado, J. & Gutiérrez, G. Compound heterozygous mutations in the SLC26A3 gene in 2 Spanish siblings with congenital chloride diarrhea. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 52, 106–110 (2011).

Choi, M. et al. Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 19096–191101 (2009).

Grzenda-Adamek, Z. & Przybyszewska, K. Celiac disease in a girl with congenital chloride diarrhea: coincidence of 2 diarrheal disorders. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 47, 504–506 (2008).

Heinz-Erian, P. et al. A novel homozygous SLC26A3 nonsense mutation in a Tyrolean girl with congenital chloride diarrhea. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 47, 363–366 (2008).

Tsukimori, K., Nakanami, N., Wake, N., Masumoto, K. & Taguchi, T. Prenatal sonographic findings and biochemical assessment of amniotic fluid in a fetus with congenital chloride diarrhea. J. Ultrasound Med. 26, 1805–1807 (2007).

Berni Canani, R. et al. Butyrate as an effective treatment of congenital chloride diarrhea. Gastroenterolgy 127, 630–634 (2004).

Nadia, M., Al-Hamad, Amal, A. & Al-Eisa Renal abnormalities in congenital chloride diarrhea. Saudi Med J. 25, 651–655 (2004).

Kim, S. H. & Kim, S. H. Congenital chloride diarrhea: antenatal ultrasonographic findings in siblings. J. Utrasound Med. 20, 1133–1136 (2001).

Yoshikawa, H., Watanabe, T., Abe, T., Sato, M. & Oda, Y. Japanese siblings with congenital chloride diarrhea. Pediatr. Int. 42, 313–315 (2000).

Al-Abbad, A., Nazer, H., Sanjad, S. A. & Al-Sabban, E. Congenital chloride diarrhea: a single center experience with ten patients. Ann. Saudi Med. 15, 466–469 (1995).

Asano, T. et al. A girl having congenital chloride diarrhea treated withspironolactone for seven years. Acta Paediatr. Jpn 36, 416–418 (1994).

Breuer, J., Rebmann, H., Rosendahl, W. & Vochem, M. Chronic metabolic alkalosis in a newborn infant causedby congenital chloride diarrhea. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 141, 207–210 (1993).

Evanson, J. M. & Stanbury, S. W. Congenital chloridorrhoea or so-called congenital alkalosis with diarrhoea. Gut 6, 29–38 (1965).

Lee, Y. D., Lee, H. J. & Moon, H. R. Congenital chloridorrhea in Korean infants. J. Korean Med. Sci. 3, 123–129 (1988).

Sakallı, H. & Bucak, H. İ. Type IV neonatal Bartter syndrome complicated with congenital chloride diarrhea. Am. J. Case Rep. 13, 230–233 (2012).

Höglund, P., Holmberg, C., Sherman, P. & Kere, J. Distinct outcomes of chloride diarrhoea in two siblings with identical genetic background of the disease: implications for early diagnosis and treatment. Gut 48, 724–727 (2001).

Fuwa, K. et al. Japanese neonate with congenital chloride diarrhea caused by SLC26A3 mutation. Pediatr. Int. 57, 11–13 (2015).

Valavi, E., Javaherizadeh, H., Hakimzadeh, M. & Amoori, P. Improvement Of congenital chloride diarrhea with corticosteroids: an incidental finding. Pediatr. Health Med. Ther. 10, 153–156 (2019).

Pieroni, K. P. & Bass, D. Proton pump inhibitor treatment for congenital chloride diarrhea. Dig. Dis. Sci. 56, 673–676 (2011).

Sajid, A., Riaz, S., Riaz, A. & Safdar, B. Congenital chloride diarrhoea. BMJ Case Rep. 12, 229012–229014 (2019).

Gujrati, K., Rahman, A. J. & Gulsher Congenital chloride losing diarrhoea. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 64, 339–341 (2014).

Colombani, M., Ferry, M. & Toga, C. Magnetic resonance imaging in the prenatal diagnosis of congenital diarrhea. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 35, 560–565 (2010).

Berni Canani, R. et al. Genotype-dependency of butyrate efficacy in children with congenital chloride diarrhea. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 8, 194–201 (2013).

Bhardwaj, S. et al. Congenital chloride diarrhea – novel mutation in SLC26A3 gene. Indian J. Pediatr. 83, 859–861 (2016).

Lee, D. H. & Park, Y. K. Antenatal differential diagnosis of congenital chloride diarrhea: a case report. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 38, 957–961 (2012).

Dechant, M. J. et al. Follow-up of a child with congenital chloride diarrhoea caused by a novel mutation. Acta Paediatr. 101, 256–259 (2012).

Hosoyamada, T. Clinical studies of pediatric malabsorption syndromes. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi. 97, 322–350 (2006).

Guo, H., Zheng, B. X. & Jin, Y. A novel missense mutation Q495K of SLC26A3 gene identified in a Chinese child with congenital chloride-losing diarrhoea. Acta Paediatr. 106, 1004–1005 (2017).

Liaugaudiene, O., Stoniene, D., Kucinskiene, R., Buffat, C. & Asmoniene, V. Case report on a rare disease in Lithuania: congenital chloride diarrhea. J. Pediatr. Genet. 8, 24–26 (2019).

Imada, S. et al. Prenatal diagnosis and management of congenital chloride diarrhea: a case report of 2 siblings. J. Clin. Ultrasound 40, 239–242 (2012).

Iijima, S. & Ohzeki, T. A case of congenital chloride diarrhea: information obtained through long-term follow-up with reduced electrolyte substitution. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 1, 28–31 (2008).

Aichbichler, B. W., Zerr, C. H., Santa Ana, C. A., Porter, J. L. & Fordtran, J. S. Proton-pump inhibition of gastric chloride secretion in congenital chloridorrhea. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 106–109 (1997).

Hadhami Ben, Turkia et al. Congenital chloride diarrhea in two Yemeni siblings. Bahrain Med. Bull. 40, 178–180 (2018).

Hihnala, S. et al. Long-term clinical outcome in patients with congenital chloride diarrhea. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 42, 369–375 (2006).

Elrefae, F., Elhassanien, A. F. & Alghiaty, H. A. Congenital chloride diarrhea: a review of twelve Arabian children. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 6, 71–75 (2013).

Kamal, N. M., Khan, H. Y., El-Shabrawi, M. H. F. & Sherief, L. M. Congenital chloride losing diarrhea: a single center experience in a highly consanguineous population. Medicine (Baltimore) 98, 15928–25936 (2019).

Lechner, S. et al. Significance of molecular testing for congenital chloride diarrhea. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 53, 48–54 (2011).

Amato, F. et al. Twelve novel mutations in the SLC26A3 gene in 17 sporadic cases of congenital chloride diarrhea. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 65, 26–30 (2017).

Thain, E. et al. Prenatal and preconception genetic counseling for consanguinity: consanguineous couples’ expectations, experiences, and perspectives. J. Genet. Couns. 28, 982–992 (2019).

Wedenoja, S., Höglund, P. & Holmberg, C. Review article: the clinical management of congenital chloride diarrhoea. Aliment Pharm. Ther. 31, 477–485 (2010).

Ding, X. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α acts reciprocally with solute carrier family 26, member 3, (downregulated-in-adenoma) and reduces its expression, leading to intestinal inflammation. Int J. Mol. Med. 41, 1224–1232 (2018).

Asano, K. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies three new susceptibility loci for ulcerative colitis in the Japanese population. Nat. Genet. 41, 1325–1329 (2009).

Iijima, S. Suicide attempt using potassium tablets for congenital chloride diarrhea: a case report. World J. Clin. Cases 8, 1463–1470 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.D.M., G.C., and R.B.C. ideated the research, performed data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, and wrote the original draft. C.M. and A.P. participated in the data acquisition and in drafting the paper. G.C., M.G., and M.V.E. reviewed critically the paper and edited the final draft. All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Di Meglio, L., Castaldo, G., Mosca, C. et al. Congenital chloride diarrhea clinical features and management: a systematic review. Pediatr Res 90, 23–29 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01251-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01251-2

This article is cited by

-

Approach to Congenital Diarrhea and Enteropathies (CODEs)

Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2023)

-

Prenatal diagnosis of congenital chloride diarrhea by whole exome sequencing in four Chinese families and prenatal genotype–phenotype association study

World Journal of Pediatrics (2023)