Abstract

The quantity and quality of child-directed speech—language nutrition—provided to typically-developing children is associated with language outcomes—language health. Limited information is available about child-directed speech to children at biological risk of language impairments. We conducted a scoping review on caregiver child-directed speech for children with three clinical conditions associated with language impairments—preterm birth, intellectual disability, and autism—addressing three questions: (1) How does child-directed speech to these children differ from speech to typically-developing children? (2) What are the associations between child-directed speech and child language outcomes? (3) How convincing are intervention studies that aim to improve child-directed speech and thereby facilitate children’s language development? We identified 635 potential studies and reviewed 57 meeting study criteria. Child-directed speech to children with all conditions was comparable to speech to language-matched children; caregivers were more directive toward children with disorders. Most associations between child-directed speech and outcomes were positive. However, several interventions had minimal effects on child language. Trials with large samples, intensive interventions, and multiple data sources are needed to evaluate child-directed speech as a means to prevent language impairment. Clinicians should counsel caregivers to use high quality child-directed speech and responsive communication styles with children with these conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the 21st century, language skills have become linked to long-term academic, occupational, financial, and social success.1,2 Success in school and work rely on higher-level cognitive and social abilities, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaboration, all shaped by language skills. The roots of language are established early in infancy and throughout the preschool period. Individual differences in language skills when children reach school-age typically persist throughout childhood.3 Delays in language development are associated with disorders of reading, spelling, writing4, and with mental health problems.5 Because of life-long implications, monitoring children’s language, their “language health”, through surveillance and screening in the preschool period, is fundamental to health supervision.6

“Child-directed speech” or “language nutrition”7 refers to verbal speech input and accompanying nonverbal gestures directed to the child within social interactions. In this review, we restrict child-directed speech to input from parents, relatives, or caregivers in the home. “Language nutrition” is characterized in terms of quantity and quality of linguistic and nonlinguistic input and the nature of caregiver–child verbal interactions (Fig. 1).7,8 Among typically-developing children, language nutrition has been associated with individual differences in child language skills,8,9 though the associations vary as a function of the child’s age or stage of language development.8 Disparities in child language outcomes as a function of socioeconomic status have been attributed, in large part, to differences in language nutrition.10,11,12 Interventions that increase child-directed speech to children from lower socioeconomic status backgrounds have been shown to successfully increase language nutrition and improve at least some child language outcomes.13,14,15,16,17 Evidence that language nutrition improves language health in children at risk for language impairments due to low socioeconomic status is accumulating.15,16,17 When these interventions are delivered to typically-developing children before children have experienced language delays, they qualify as primary prevention.18,19

“Language impairments” refer to delays or disorders in language skills relative to age expectations. Children with persistent language impairments struggle with social relationships, literacy, employment, and mental health in adulthood.20 Limited information is available about the role of language nutrition in children with clinical conditions that constitute biological risk for language impairments. Investigating their ability to learn from child-directed speech would provide insights about mechanisms of language learning in diverse populations. If studies find that child-directed speech leads to favorable outcomes in these children, the results could lead to public health, education, and clinical programs to improve language nutrition for these children. Language nutrition programs would then qualify as secondary or tertiary prevention for language health.18 Secondary prevention implies that, in the case of a clinical condition, improved child-directed speech results in less severe manifestations of language impairments than would have occurred without the intervention. Tertiary prevention implies that improved child-directed speech does not change language impairments, but, nonetheless, leads to better functional outcomes than would have occurred without the intervention.

We undertook a scoping review in order to assess the breadth, nature, and types of research studies available to address the role of language nutrition in children with clinical conditions associated with language impairments. A scoping review was more appropriate than a systematic review because our interests went beyond consideration of a specific treatment or narrow question that would have been addressed with a systematic review. We sought to conduct a general survey of a diverse literature to identify similarities and differences across conditions and to expose gaps in the literature to guide future research.21 The three populations chosen were preterm birth (PT), intellectual disability (ID), and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). PT children, on average, function below peers born full term (FT) in language skills, though many perform in the normal range.22,23 Children with ID, including those with a diagnosis of Down Syndrome (DS)24 or Fragile X (FXS),25 score substantially below the expected range in language skills, and lower in verbal than nonverbal skills. Children with ASD often present with speech and language impairments in addition to the defining social communication deficit; they show a range of language abilities over development.26,27 Recognizing that these conditions vary in age of identification, presentation, and severity of language impairments, we wanted to consider similarities and differences in nature and impact of language nutrition across them for theoretical and clinical reasons. We asked three questions about the current state of the literature and the gaps in the empirical base regarding language nutrition for these populations:

Question 1. How does child-directed speech addressed to children at biological risk of language impairments differ from child-directed speech addressed to typically-developing (TD) children?

Question 2. What are the associations between child-directed speech and subsequent language development in children at biological risk for language impairments?

Question 3. How convincing are intervention studies designed to increase child-directed speech and, as a result, improve children’s language development in these populations of children?

Methods

Study selection

Following Arksey and O’Malley’s framework,21 we conducted an electronic database search of PubMed for English-language literature for 2000–2019. We began in 2000 because since 2000, care of PT children has stabilized. That year also marked publication of the DSM-IV TR,28 adjusting diagnostic criteria for ASD. Keywords were combined using Boolean logic and included the criteria to focus on child-directed speech within the three clinical conditions (Table 1). Children with ID were defined as having an IQ below 70 on standardized assessments and included children with developmental delay (DD) and genetic/chromosomal conditions, such as DS and FXS. Studies of children diagnosed with ASD who also scored in the range of ID were classified as ASD.

Studies were reviewed by at least two raters. Inclusion criteria were generated based on categories of caregiver–child interactions29 (Fig. 1). We limited the review to empirical studies (no reviews or case reports) in which caregiver behaviors were assessed objectively, using laboratory or home observations of caregiver–child interaction, family-collected home videos, or day-long home audio recordings.30,31 These methods provided quantitative assessments on interval scales (e.g., adult word count/hour, average sentence complexity) or ordinal scales (e.g., rating of responsiveness, intrusiveness). We excluded studies which explored caregiver speech in the following ways: (1) caregivers provided self-reports of child-directed speech; (2) socioeconomic status, caregiver education, or other demographic variables served as a proxy for features of child-directed speech; (3) the focus was on teacher or therapist language, unless caregiver behavior was also evaluated; (4) fidelity to an intervention was assessed without explicit discussion of features of child-directed speech; (5) measures included only nonverbal input, such as touch or massage; and (6) evaluations focused on developmental domains other than speech, language, communication, or verbal cognition/intelligence (IQ). Studies also met the following criteria: (1) mean age of the children was less than 6 years at initial observation, though longitudinal studies could follow the child to older ages; (2) descriptive studies had a comparison group of caregivers of TD children; and (3) association and intervention studies described or intervened on child-directed speech. Studies of siblings of children with ASD were included if those children who developed ASD were described separately from the siblings who did not. If two papers evaluated the same cohort but one reported on associations and the other on interventions, we included the intervention study. If two studies included the same children, but reported on child outcomes at a later time point, then the latter was chosen. If the same sample was used in two studies but analyzed different aspects of child-directed speech or different outcomes, we included all studies.

For Question 1, the study designs compared the children with biological conditions to TD children matched either on chronological age or on language ability. For Question 2, a comparison group of TD children was not required. However, we restricted the review to studies that considered the association of child-directed speech at a younger age to child language skills at an older age. For Question 3, we considered intervention studies that were either single subject multiple baseline designs or clinical trials with random assignment.

Results

Search results

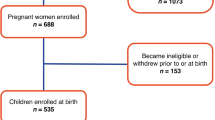

A summary of the database search and selection process is shown in Fig. 2. The electronic database search identified 635 studies. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 491 studies were excluded. Researchers then conducted full-text review of the resulting 144 studies and 87 were rejected because they did not meet established criteria. A total of 57 manuscripts were extracted for analyses. Of these, 15 addressed children born PT, 13 addressed children with ID, 32 addressed children with ASD. Three of these studies included children from two different clinical populations. Supplementary Table S1 includes all of the studies reviewed.

Child-directed speech for children with biological conditions vs. TD children

Preterm birth (PT)

Eight studies compared child-directed speech to PT and FT children, matched on age corrected for the degree of prematurity.32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 Metrics were diverse but assessed similar behavioral constructs. One study of home audio-recordings found no differences in the adult word count between PT and FT groups.32 Seven studies evaluated linguistic or verbal interaction quality from home or laboratory observations.33,34,35,36,37,38,39 Caregivers of PT children used less complex verbal scaffolding (i.e., less elaboration on the child’s output) than caregivers of FT children.38 Studies found no differences in responsiveness or engagement between caregivers of PT vs. FT children.34,35,36,39 However, intrusiveness and demandingness, tendencies to lead the child rather than follow the child’s communication, was higher among caregivers of PT children in two34,37 of three studies.36 Infant–caregiver synchrony was comparable in PT and FT dyads in one study,34 but lower in another.37 In summary, though studies found that child-directed speech to PT vs. FT children was more intrusive and composed of less complex scaffolding, similarities were noted in the quantity of words and verbal interaction measures of responsiveness or engagement.

Intellectual disability (ID)

Seven studies compared child-directed speech to children with ID vs. TD.40,41,42,43,44,45,46 Two studies of home audio recordings reported that adult word counts were lower for groups with DS42 and FXS43 than a chronological age-matched TD group, but similar for children with FXS and a developmentally-matched TD group.43 These studies used a comparison group from a large normative sample of TD children; the methods for age- and developmental-age matching were not well described, potentially introducing bias. Studies comparing linguistic quality used diverse methods. One study of DS vs. language-matched TD children found no differences in information-salient speech (e.g., descriptions), but greater affect-salient speech (e.g., encouragement) to children with DS.45 Two studies evaluated teaching of new words. One found no differences in how caregivers taught novel words to DS and language-matched children;44 the other reported subtle differences in quantity of talk when introducing nouns in different contexts and sentence complexity when introducing novel verbs.40 In verbal interactions, one home observation study reported that mothers of DS vs. age-matched TD children used fewer facilitating behaviors. While overall directive behaviors did not differ between groups, mothers of children with DS used directive behaviors at older child ages than mothers of TD children.41 Caregivers of DS and TD children spent similar amounts of time in caregiver–child joint engagement when groups were language-matched.46 Though few studies were found, these findings indicated that favorable aspects of language nutrition did not differ dramatically between ID and developmental- or language-matched TD groups. Subtle differences were restricted to qualitative features, such as how caregivers used specific nouns and verbs, and affect-salient speech.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

Fourteen studies compared child-directed speech with ASD and TD children.44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57 Studies comparing language-matched groups found no differences in the quantity of child-directed speech during laboratory sessions, home observations, and day-long audio recordings.49,51,52 Similarities between groups were noted in qualitative linguistic features, including number of different words,49,51 wh-questions (e.g,. questions about object and location),50 gestures,56 affect-salient speech, and information-salient speech.45 However, in comparison to caregivers of TD children, caregivers of ASD children showed reduced total number of wh-questions45,50 and increased information-salient speech via directive statements.45 One study did not find differences in sentence complexity51 while another study that examined caregivers across multiple timepoints found reduced sentence complexity in caregivers of children with ASD.49

Findings were mixed in studies of verbal interactions.44,46,47,48,52,53,54,55,56,57 Studies matching on chronological age or language age reported reduced conversational turns or engagement in dyads with ASD vs. TD children.46,52 In contrast, studies matching on language abilities noted similar verbal interactions between ASD and TD groups.46,48,55,57 One study, where matching was unspecified, evaluated 13,000 recorded hours from day-long recordings in a large sample53 and found that though adult responses to child vocalizations occurred less frequently for ASD vs. TD children, the same social feedback loop was present in both groups: adults responded to children and children responded to adults. Studies that examined how caregivers of children with ASD teach novel words found similar teaching strategies for ASD and language-matched TD children.44,54 Studies also compared infants at high familial risk who were later diagnosed with ASD vs. infants at high or low familial risk who never received the diagnosis. These studies indicated no differences between groups in the quantity and quality of child-directed speech.47,56 Overall, the majority of studies indicated many similarities and few differences in the quantity, quality, and reciprocal verbal interaction of child-directed speech to children with ASD vs. TD children. A few studies documented that caregivers of children with ASD vs. language-matched TD children demonstrated modest reductions in favorable features, such as number of questions and sentence complexity.

Associations between child-directed speech and subsequent child language skills

PT birth

Twelve studies examined the relation between child-directed speech and later language outcomes in PT children.32,33,34,35,36,58,59,60,61,62,63,64 Quantity, quality, and verbal interaction of child-directed speech were associated with later language skills in children born PT. Mean adult word counts in the neonatal intensive care unit correlated with developmental assessments at 7 and 18 months of age.61 Adult word counts at 18 months showed positive associations with language scores and parent ratings later in the toddler years.32 Quality metrics of number of different words, sentence complexity,60 mind-mindedness,33 and gestures paired with relevant descriptive speech62 were also associated positively with different language outcomes. Multiple studies found that more responsive caregivers had children with better receptive and expressive language outcomes.34,35,63,64 However, minimal maternal responsiveness negatively affected outcomes in PT children.58 Caregiver directiveness at 2 years was found to be positively related to skills 1 year later, while directiveness at 3.5 years was negatively related to skills in the next year.36 Together, studies demonstrated consistent evidence of positive associations between numerous favorable features of child-directed speech and children’s outcomes in children born PT.

Intellectual disability (ID)

Three studies examined longitudinal associations between child-directed speech and later language outcomes in children with FXS.65,66,67 One study examined children with DS46 and one study examined children with low scores on developmental testing.68 Caregivers’ gestures were positively associated with receptive and expressive language 3 years later in children with FXS,66 although early child variables were not accounted for in the analyses. Caregiver responsiveness was positively associated with children’s language outcomes, after controlling for children’s developmental level and caregiver education.65,67 Caregivers’ use of linguistic mapping (i.e., providing language for children’s communication acts) was found to mediate the relation between children’s early babbling and children’s later language.68 Symbol-infused joint engagement, interactions using words and other symbols, was also positively related to children’s receptive and expressive language 1 year later.46 Though the literature is very limited, the results were consistent with studies of PT children; features of child-directed speech were positively associated with children’s language outcomes.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

Fourteen studies examined the relation between child-directed speech and later language and social communication outcomes in children with ASD.46,47,49,50,51,56,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76 Consistently, after accounting for children’s initial language abilities, studies found greater caregiver sentence complexity was positively associated with children’s later language outcomes.49,51 Positive associations were also seen in the number of caregivers’ wh-questions and children’s subsequent comprehension of wh-questions.50 Multiple studies found that following into children’s focus of attention with directive language or commenting was associated with positive language outcomes assessed after 6 months - 1 year,69,70,71,72 1.5 years,74 and 3 years.73 Expansions of children’s language, another example of responsiveness, was positively related to language outcomes.72 By contrast, redirecting children’s attention was found to be negatively associated with later language development.73 Studies measuring caregiver–child engagement demonstrated that more time in symbol-infused joint engagement was associated with better child language outcomes.46 Studies of younger siblings of children with ASD who later met criteria for ASD found mixed results. One found positive associations of maternal sensitivity and children’s later expressive language;47 another reported null relations.56 In summary, greater sentence complexity, more responsive child-directed speech, and higher quality engagement were generally associated with better language skills in ASD children.

Interventions to increase or improve child-directed speech

PT birth

The search identified only one intervention study, a randomized clinical trial, with children born PT.58 Mothers who were trained to increase seven interactive behaviors showed greater warmth and responsiveness than mothers receiving a control intervention. PT children in the treatment vs. control group showed greater gains in child initiations to the caregiver and cognitive test scores.

Intellectual disability (ID)

Two interventions focused on child-directed speech to children with mixed etiologies of ID.77,78 These randomized trials compared a therapist-administered training with or without additional caregiver responsivity training,77,78 In both, caregivers in the treatment group showed greater responsivity after training than caregivers in the control group. One found no effect in children’s language outcomes.77 An exploration of moderators77 revealed that children with low initial language abilities and children who did not have DS in the treatment group performed better after treatment than did the other participants. The other study found positive language outcomes in the children that were maintained 6 and 12 months post intervention.78

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

The search identified ten interventions of child-directed speech with children with ASD76,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87 and one intervention with younger siblings of children with ASD.88 Six studies used randomized clinical trials.79,80,81,82,83,88 In five, the primary outcome was a metric of language or child communication,79,80,82,83,88 and in one, the primary outcome was autism symptoms.81 While the specific interventions were diverse, all included a focus on improving parental responsivity or synchrony. The results of these trials showed that treatment effects on directly-observed spontaneous child language were minimal, with no statistically different improvements from baseline to post-intervention and small effect sizes.

The degree to which child-directed speech and child language outcomes improved or increased as a result of the intervention varied widely across studies. Two studies found no intervention effects on caregiver responsiveness or on general verbal interaction metrics;80,83 two other studies found improved caregiver responsiveness or synchrony.81,88 Minimal effects on child outcomes were seen in metrics from natural language samples, such as child intentional communication or spontaneous utterances80,82 or in standardized metrics of receptive or expressive language.79,81,88 Language outcomes assessed via parent report were mixed; one study found large intervention effects81 and another found no effects.83

Multiple potential moderators were identified that may have accounted for variation in study results. Children with lower levels of object interest made greater gains in their use of intentional communication than children with higher object interest.80 Children with expressive language scores below an age equivalent of 12 months made greater gains in their later expressive language than those with better language skills.79 Caregivers who showed greater insightfulness had children who made greater gains.79 Five studies used study designs other than clinical trials, including four with multiple baseline designs.76,84,85,86,87 Some of these studies reported varying degrees of improved child outcomes. However, the lack of a control group and small sample sizes makes results susceptible to bias.

Discussion

This scoping review assessed the breadth, nature, and types of research studies on child-directed speech as a secondary or tertiary prevention strategy for children with three biological conditions associated with language impairments: PT birth, ID, and ASD. Overall, the available literature was limited and highly diverse in terms of methods, metrics of child-directed speech, and child outcomes. The largest number of studies, including clinical trials of interventions, addressed ASD. The limited literature is unfortunate for both theoretical reasons, restricting our understanding of the mechanisms of learning in these children, and for clinical reasons, hindering our ability to provide caregivers with definitive evidence-based guidance about supporting their children.

Child-directed speech to children with biological conditions compared with TD children

The findings across conditions converged on the conclusion that caregivers of children with biological conditions, in the aggregate, showed many similar features of language nutrition as caregivers of TD children matched for language level, not chronological age. Consistent differences were higher levels of intrusiveness or directiveness to children with clinical conditions than to TD children. Although increased or enriched language nutrition may be considered to be beneficial for children with biological conditions, none of the studies found that caregivers as a group enriched their input to greater levels than that of language-matched peers. One likely explanation was that caregivers were sensitive to their child’s developmental levels in language and matched their input to that level. These findings imply that without training, caregivers of children with clinical conditions do not spontaneously increase the quantity or improve the quality of child-directed speech, possibly missing critical opportunities to improve children’s language outcomes.

Child-directed speech and subsequent child language skills

For all three conditions, many features of child-directed speech were consistently and positively associated with children’s later language outcomes. The exception was intrusiveness, or redirecting the child’s focus of attention, which was consistently negatively associated with outcomes. Many, but not all, studies controlled for the child’s language or other cognitive skills at baseline, a critical design feature required to conclude that child-directed speech contributed to children’s language outcomes over and above their initial abilities.8 In short, high quality language nutrition was positively associated with later language abilities, as has been demonstrated for TD children.

Interventions to increase or improve child-directed speech

The literature addressing the question of intervention effectiveness was extremely limited and diverse. Even among the clinical trials for children with ASD, the methods varied widely in terms of design, child-directed speech metrics, and child language outcomes. In general, impacts on child language outcomes when measured objectively were minimal.79,80,81,82,83,88 The exceptions suggested the importance of an intensive program. The randomized trial for PT children that was successful at improving caregivers’ child-directed speech and child outcomes of cognition and child initiations provided 12 weeks of in-home caregiver training.58 The successful trial for children with ID trained parents over 36 weeks, finding immediate and sustained positive effects on children’s language outcomes 12 months post intervention.78 A comparative effectiveness study for ASD found that 24 sessions of caregiver-mediated intervention with the child present was more effective than small-group caregiver education without the child present in increasing the child’s joint attention.89 Differences in interventions may explain variability in previous reviews. A recent meta-analysis,90 focusing on parent-mediated interventions in children with ASD, reported only modest effects for children’s language and communication outcomes, and no differences on outcomes based on dosage. However, another meta-analysis, focusing on caregiver-implemented language interventions to children with several different biological conditions, concluded positive effects on at least some language outcomes.29

Several factors may have limited the effectiveness of interventions on language nutrition in the clinical groups. Children were likely receiving additional intervention(s) while participating in studies; thus, interventions had to demonstrate substantial unique caregiver contributions to detect child improvements above other interventions. Interventions varied widely in the type of training; some used parent groups while others used one-on-one coaching with parents and children together. Interventions also varied in intensity, as indexed by number of sessions or hours of intervention. To make a substantial impact, the literature suggests that interventions must be sustained over time, and occur, at least in part, with caregivers and their children together.29 In this way, caregivers see role models in action and receive extensive practice and feedback on their child-directed speech. These features reduce the challenges of translating knowledge into practice or generalizing to new situations. Such caregiver-directed interventions can be integrated into child-focused early intervention or school programs to coordinate content, facilitate caregiver participation, and leverage the training directly impacting the child.

Intervention studies also varied in terms of what particular aspect(s) of language nutrition were targeted. The majority of studies focused on verbal interaction, such as improving responsivity. The study descriptions lacked detail on whether or how they addressed improving quantity and quality of child-directed speech. Given that caregivers did not tend to spontaneously enrich their input to children, explicit training on the quantity and quality of child-directed speech is likely an important ingredient to effectively boost children’s language. Studies on children at biological risk for language impairments may benefit from closer alignment to studies of children at psychosocial risk, though we recognize that explicit direct training of caregivers of TD children has not consistently resulted in large and sustained effects of child language.16

Agenda for research

Several areas of future research are critically necessary to optimize our understanding of secondary and tertiary prevention of language impairments via child-directed speech in clinical populations. Firstly, future work should continue to consider psychological and neurobiological mechanisms behind associations between language nutrition and language health.91,92 We have much to learn about the causal pathways for why language nutrition is linked to children’s language health for typically-developing children and we need to know whether or not the pathways are similar or different in children with biological conditions. Regarding intervention, randomized clinical trials are critical because they allow direct comparisons of intervention and control groups and can establish causality of the intervention. We recommend that interventions test targets of linguistic quantity and quality as well as verbal interactions.78 It is critical that future work also plan and test moderators of intervention effectiveness a priori, identifying which children and caregivers benefit most from intervention. Little is known about what aspects of language nutrition are the easiest for caregivers to generalize naturally to everyday interactions with their children. Combining methods, such as laboratory or home observations with day-long audio recordings, can help address generalizability.

Large studies performed by research networks may overcome the limitations of small studies using diverse methodologies.93 In terms of measuring outcomes, it is important to incorporate developmental and/or behavioral evaluations with standardized measures to assess a wide range of results across studies.93 By including children with PT, ID, ASD, or other language impairments in large studies aimed at improving language skills in children at psychosocial risk, effect sizes for children with biological conditions can be compared with those of children without clinical conditions. Future research is also needed to understand the best method, intensity, and dose of interventions required to affect children’s outcomes.29,90 Interventions may need to be customized to children’s level of language and social skills or to the characteristics of the caregivers’ child-directed speech.94 Future studies should enroll speakers of languages other than English, or speakers of multiple languages, and investigate the combined impact of psychosocial (e.g., socioeconomic status, stress, or depression in caregivers) and biological risk factors on children’s language nutrition and health.89

Clinical implications

Though the intervention studies were inconclusive, consistent positive associations between child-directed speech and children’s later language outcomes in all three conditions suggest that language nutrition may affect long-term child outcomes. It is important to inform caregivers of children of these findings. Caregivers should be encouraged to speak to their child often, use full sentences with diverse vocabulary, and to respond to children’s overtures. Caregivers should avoid overly simplified language, such as short phrases that lack grammatical markers,75 which has been shown to be negatively related to children’s language outcomes. The use of complete grammatical sentences may be particularly important for children with ASD, where greater sentence complexity is positively associated with children’s language outcomes.49,51,95 While these changes may not substantially reduce the severity of language impairments, exposing children to rich language nutrition may, at a minimum, subtly improve the trajectory of development and lead to improved functional outcomes in children with these clinical conditions.

Conclusion

Child-directed speech to children with PT birth, ASD, and ID was similar to child-directed speech to language-matched TD children. Quantity of talk, linguistic quality of utterances, and the proportion of supportive and responsive verbal interactions were positively associated with later child language outcomes, though intervention studies did not consistently find major improvements in outcomes. Additional intervention studies are required to determine if improved child-directed speech prevents or ameliorates language impairments in these populations. The failure of caregivers to spontaneously enrich child-directed speech warrants counseling with caregivers of children with biological disorders about their potential role in improving the language nutrition of their children, thereby, supporting language health.

References

Durham, R.E., Farkas, G., Hammer, C.S., Tomblin, J.B. and Catts, H.W. Kindergarten oral language skill: A key variable in the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 25, 294–305 (2007).

Carnevale, A. P., Smith, N., Strohl, J. Help wanted: projection of jobs and education requirements through 2018: Executive Summary [Internet]. (Georgetown University Center on Education and the Work Force, Washington DC, 2010). https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/HelpWanted.ExecutiveSummary.pdf.

Conti-Ramsden, G., Botting, N. & Faragher, B. Psycholinguistic markers for specific language impairment (SLI). J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 42, 741–748 (2001).

Schoon, I., Parsons, S., Rush, R. & Law, J. Childhood language skills and adult literacy: a 29-year follow-up study. Pediatrics 125, e459–e466 (2010).

Schoon, I., Parsons, S., Rush, R. & Law, J. Children’s language ability and psychosocial development: a 29-year follow-up study. Pediatrics 126, e73–e80 (2010).

Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics 118, 405–420 (2006).

Head Zauche, L. et al. The power of language nutrition for children’s brain development, health, and future academic achievement. J. Pediatr Health Care. 31, 493–503 (2017).

Rowe, M. L. A longitudinal investigation of the role of quantity and quality of child-directed speech in vocabulary development. Child Dev. 83, 1762–1774 (2012).

Weizman, Z. O. & Snow, C. E. Lexical output as related to children’s vocabulary acquisition: effects of sophisticated exposure and support for meaning. Dev. Psychol. 37, 265–279 (2001).

Hart B., Risley T. R. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young american children. (Brookes Publishing, Baltimore, MD, 1995). 308 https://products.brookespublishing.com/Meaningful-Differences-in-the-Everyday-Experience-of-Young-American-Children-P14.aspx.

Hoff, E. The specificity of environmental influence: socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child. Dev. 74, 1368–1378 (2003).

Daneri M. P., Blair C., Kuhn L. J. Maternal language and child vocabulary mediate relations between socioeconomic status and executive function during early childhood. Child. Dev. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13065 (2019).

Anthony, J. L., Williams, J. M., Zhang, Z., Landry, S. H. & Dunkelberger, M. J. Experimental evaluation of the value added by raising a reader and supplemental parent training in shared reading. Early Educ. Dev. 25, 493–514 (2014).

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R. & Guttentag, C. A responsive parenting intervention: the optimal timing across early childhood for impacting maternal behaviors and child outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 44, 1335–1353 (2008).

Leffel, K. & Suskind, D. Parent-directed approaches to enrich the early language environments of children living in poverty. Semin. Speech Lang. 34, 267–278 (2013).

Suskind, D. L. et al. A parent-directed language intervention for children of low socioeconomic status: a randomized controlled pilot study. J. Child Lang. 43, 366–406 (2016).

Burgoyne, K., Gardner, R., Whiteley, H., Snowling, M. J. & Hulme, C. Evaluation of a parent-delivered early language enrichment programme: evidence from a randomised controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59, 545–555 (2018).

Simeonsson, R. J. Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention in early intervention. J. Early Interv. 15, 124–134 (1991).

Caplan, G. & Grunebaum, H. Perspectives on primary prevention: a review. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 17, 331–346 (1967).

Levy, A. & Perry, A. Outcomes in adolescents and adults with autism: a review of the literature. Res Autism Spectr. Disord. 5, 1271–1282 (2011).

Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J. Soc. Res Methodol. 8, 19–32 (2005).

Barre, N., Morgan, A., Doyle, L. W. & Anderson, P. J. Language abilities in children who were very preterm and/or very low birth weight: a meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. 158, 766–774.e1 (2011).

van Noort-van der Spek, I. L., Franken, M.-C. J. P. & Weisglas-Kuperus, N. Language functions in preterm-born children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 129, 745–754 (2012).

Chapman, R. S. & Hesketh, L. J. Behavioral phenotype of individuals with Down syndrome. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 6, 84–95 (2000).

Philofsky, A., Hepburn, S. L., Hayes, A., Hagerman, R. & Rogers, S. J. Linguistic and cognitive functioning and autism symptoms in young children with fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 109, 208–218 (2004).

Kjelgaard, M. M. & Tager-Flusberg, H. An investigation of language impairment in autism: implications for genetic subgroups. Lang. Cogn. Process. 16(2–3), 287–308 (2001).

Wittke K., Mastergeorge A. M., Ozonoff S., Rogers S. J., Naigles L. R. Grammatical language impairment in autism spectrum disorder: exploring language phenotypes beyond standardized testing. Front Psychol. 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/ https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00532/full (2017).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th ed., Text Revision. (Washington DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Roberts, M. Y. & Kaiser, A. P. The effectiveness of parent-implemented language interventions: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 20, 180–199 (2011).

Greenwood, C. R., Thiemann-Bourque, K., Walker, D., Buzhardt, J. & Gilkerson, J. Assessing children’s home language environments using automatic speech recognition technology. Commun. Disord. Q. 32, 83–92 (2011).

Richards Jeffrey, A. et al. Automated assessment of child vocalization development using LENA. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 60, 2047–2063 (2017).

Adams, K. A. et al. Caregiver talk and medical risk as predictors of language outcomes in full term and preterm toddlers. Child Dev. 89, 1674–1690 (2018).

Costantini, A., Coppola, G., Fasolo, M. & Cassibba, R. Preterm birth enhances the contribution of mothers’ mind-mindedness to infants’ expressive language development: a longitudinal investigation. Infant Behav. Dev. 49, 322–329 (2017).

Loi, E. C. et al. Quality of caregiver-child play interactions with toddlers born preterm and full term: antecedents and language outcome. Early Hum. Dev. 115, 110–117 (2017).

McMahon, G. E. et al. Influence of fathers’ early parenting on the development of children born very preterm and full term. J. Pediatr. 205, 195–201 (2019).

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R. & Miller-Loncar, C. L. Early maternal and child influences on children’s later independent cognitive and social functioning. Child Dev. 71, 358–375 (2000).

Sansavini, A. et al. Dyadic co-regulation, affective intensity and infant’s development at 12 months: a comparison among extremely preterm and full-term dyads. Infant Behav. Dev. 40, 29–40 (2015).

Lowe, J. R., Erickson, S. J., Maclean, P., Schrader, R. & Fuller, J. Association of maternal scaffolding to maternal education and cognition in toddlers born preterm and full term. Acta Paediatr. 102, 72–77 (2013).

Neri, E. et al. Preterm infant development, maternal distress and sensitivity: the influence of severity of birth weight. Early Hum. Dev. 106–107, 19–24 (2017).

Kay-Raining Bird, E. & Cleave, P. Mothers’ talk to children with Down syndrome, language impairment, or typical development about familiar and unfamiliar nouns and verbs. J. Child Lang. 43, 1072–1102 (2016).

Sterling, A. & Warren, S. F. Maternal responsivity in mothers of young children with Down syndrome. Dev. Neurorehabilitation 17, 306–317 (2014).

Thiemann-Bourque, K. S., Warren, S. F., Brady, N., Gilkerson, J. & Richards, J. A. Vocal interaction between children with Down syndrome and their parents. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 23, 474–485 (2014).

Reisinger D. L., Shaffer R. C., Pedapati E. V., Dominick K. C., Erickson C. A. A pilot quantitative evaluation of early life language development in fragile X syndrome. Brain Sci. 9, 27–39 (2019).

Adamson, L. B., Bakeman, R. & Brandon, B. How parents introduce new words to young children: the influence of development and developmental disorders. Infant Behav. Dev. 39 148–158 (2015).

Venuti, P., de Falco, S., Esposito, G., Zaninelli, M. & Bornstein, M. H. Maternal functional speech to children: a comparison of autism spectrum disorder, Down syndrome, and typical development. Res Dev. Disabil. 33, 506–517 (2012).

Adamson, L. B., Bakeman, R., Deckner, D. F. & Romski, M. Joint engagement and the emergence of language in children with autism and Down syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 39, 84–96 (2009).

Baker, J. K., Messinger, D. S., Lyons, K. K. & Grantz, C. J. A pilot study of maternal sensitivity in the context of emergent autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 40, 988–999 (2010).

Fleury, V. P. & Hugh, M. L. Exploring engagement in shared reading activities between children with autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 3596–3607 (2018).

Fusaroli, R., Weed, E., Fein, D. & Naigles, L. Hearing me hearing you: reciprocal effects between child and parent language in autism and typical development. Cognition 183, 1–18 (2019).

Goodwin, A., Fein, D. & Naigles, L. The role of maternal input in the development of wh-question comprehension in autism and typical development. J Child Lang. 42, 32–63 (2015).

Bang, J. & Nadig, A. Learning language in autism: maternal linguistic input contributes to later vocabulary. Autism Res. J. Int Soc. Autism Res. 8, 214–223 (2015).

Warren, S. F. et al. What automated vocal analysis reveals about the vocal production and language learning environment of young children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 40, 555–569 (2010).

Warlaumont, A. S., Richards, J. A., Gilkerson, J. & Oller, D. K. A social feedback loop for speech development and its reduction in autism. Psychol. Sci. 25, 1314–1324 (2014).

Bani Hani, H., Gonzalez-Barrero, A. M. & Nadig, A. S. Children’s referential understanding of novel words and parent labeling behaviors: similarities across children with and without autism spectrum disorders. J. Child Lang. 40, 971–1002 (2013).

Strid, K., Heimann, M. & Tjus, T. Pretend play, deferred imitation and parent-child interaction in speaking and non-speaking children with autism. Scand. J. Psychol. 54, 26–32 (2013).

Talbott, M. R., Nelson, C. A. & Tager-Flusberg, H. Maternal gesture use and language development in infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 4–14 (2015).

Walton, K. M. & Ingersoll, B. R. The influence of maternal language responsiveness on the expressive speech production of children with autism spectrum disorders: a microanalysis of mother-child play interactions. Autism Int J. Res Pract. 19, 421–432 (2015).

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E. & Swank, P. R. The importance of parenting during early childhood for school-age development. Dev Neuropsychol. 24(2–3), 559–591 (2003).

Foster-Cohen, S. H., Friesen, M. D., Champion, P. R. & Woodward, L. J. High prevalence/low severity language delay in preschool children born very preterm. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 31, 658–667 (2010).

Suttora, C. & Salerni, N. Maternal speech to preterm infants during the first 2 years of life: stability and change. Int J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 46, 464–472 (2011).

Caskey, M., Stephens, B., Tucker, R., & Vohr, B. Adult talk in the NICU with preterm infants and developmental outcomes. Pediatrics 133, e578-584 (2014).

Schmidt, C. L. & Lawson, K. R. Caregiver attention-focusing and children’s attention-sharing behaviours as predictors of later verbal IQ in very low birthweight children. J. Child Lang. 29, 3–22 (2002).

Cusson, R. M. Factors influencing language development in preterm infants. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 32, 402–409 (2003).

Stolt, S. et al. Early relations between language development and the quality of mother-child interaction in very-low-birth-weight children. Early Hum. Dev. 90, 219–225 (2014).

Brady, N., Warren, S. F., Fleming, K., Keller, J. & Sterling, A. Effect of sustained maternal responsivity on later vocabulary development in children with fragile X syndrome. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 57, 212–226 (2014).

Hahn, L. J., Zimmer, B. J., Brady, N. C., Swinburne Romine, R. E. & Fleming, K. K. Role of maternal gesture use in speech use by children with fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 23, 146–159 (2014).

Warren, S. F., Brady, N., Sterling, A., Fleming, K. & Marquis, J. Maternal responsivity predicts language development in young children with fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 115, 54–75 (2010).

Woynaroski, T., Yoder, P. J., Fey, M. E. & Warren, S. F. A transactional model of spoken vocabulary variation in toddlers with intellectual disabilities. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 57, 1754–1763 (2014).

Woynaroski, T. et al. Early predictors of growth in diversity of key consonants used in communication in initially preverbal children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46, 1013–1024 (2016).

Bottema-Beutel, K., Yoder, P. J., Hochman, J. M. & Watson, L. R. The role of supported joint engagement and parent utterances in language and social communication development in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 2162–2174 (2014).

Yoder, P., Watson, L. R. & Lambert, W. Value-added predictors of expressive and receptive language growth in initially nonverbal preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 1254–1270 (2015).

McDuffie, A. & Yoder, P. Types of parent verbal responsiveness that predict language in young children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res Jslhr. 53, 1026–1039 (2010).

Haebig, E., McDuffie, A. & Ellis Weismer, S. Brief report: parent verbal responsiveness and language development in toddlers on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43, 2218–2227 (2013).

Siller, M. & Sigman, M. Modeling longitudinal change in the language abilities of children with autism: parent behaviors and child characteristics as predictors of change. Dev. Psychol. 44, 1691–1704 (2008).

Venker, C. E., Bolt, D. M., Meyer, A., Sindberg, H. Ellis Weismer, S., & Tager-FlusbergH. Parent telegraphic speech use and spoken language in preschoolers with ASD. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 58, 1733–1746 (2015).

Ingersoll, B. & Wainer, A. Initial efficacy of project ImPACT: a parent-mediated social communication intervention for young children with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43, 2943–2952 (2013).

Yoder, P. J. & Warren, S. F. Effects of prelinguistic milieu teaching and parent responsivity education on dyads involving children with intellectual disabilities. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 45, 1158–1174 (2002).

Kaiser, A. P. & Roberts, M. Y. Parent-implemented enhanced milieu teaching with preschool children who have intellectual disabilities. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 56, 295–309 (2013).

Siller, M., Hutman, T. & Sigman, M. A parent-mediated intervention to increase responsive parental behaviors and child communication in children with ASD: a randomized clinical trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43, 540–555 (2013).

Carter, A. S. et al. A randomized controlled trial of Hanen’s “More Than Words” in toddlers with early autism symptoms. J Child Psychol. Psychiatry 52, 741–752 (2011).

Green, J. et al. Parent-mediated communication-focused treatment in children with autism (PACT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 375(9732), 2152–2160 (2010).

Hardan, A. Y. et al. A randomized controlled trial of Pivotal Response Treatment Group for parents of children with autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 56, 884–892 (2015).

Oosterling, I. et al. Randomized controlled trial of the focus parent training for toddlers with autism: 1-year outcome. J Autism Dev. Disord. 40, 1447–1458 (2010).

Vismara, L. A., McCormick, C., Young, G. S., Nadhan, A. & Monlux, K. Preliminary findings of a telehealth approach to parent training in autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43, 2953–2969 (2013).

Jones, E. A., Carr, E. G. & Feeley, K. M. Multiple effects of joint attention intervention for children with autism. Behav Modif. 30, 782–834 (2006).

Seung H. K., Ashwell S., Elder J. H., Valcante G. Verbal communication outcomes in children with autism after in-home father training. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 50(Pt 2):139–150 (2006).

Venker, C. E., McDuffie, A., Ellis Weismer, S. & Abbeduto, L. Increasing verbal responsiveness in parents of children with autism:a pilot study. Autism Int J. Res Pract. 16, 568–585 (2012).

Kasari, C. et al. Randomized controlled trial of parental responsiveness intervention for toddlers at high risk for autism. Infant Behav. Dev. 37, 711–721 (2014).

Kasari, C. et al. Caregiver-mediated intervention for low-resourced preschoolers with autism: an RCT. Pediatrics. 134, e72–e79 (2014).

Nevill, R. E., Lecavalier, L. & Stratis, E. A. Meta-analysis of parent-mediated interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 22, 84–98 (2018).

Romeo R. R., et al. Beyond the 30-million-word gap: children’s conversational exposure is associated with language-related brain function. Psychol. Sci. 29, 700–710 (2018).

Weisleder, A. & Fernald, A. Talking to children matters: early language experience strengthens processing and builds vocabulary. Psychol. Sci. 24, 2143–2152 (2013).

Zwaigenbaum L., et al. Early intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder under 3 years of age: recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics 136(Supplement 1):S60–S81 (2015).

Ramírez, N. F., Lytle, S. R., Fish, M. & Kuhl, P. K. Parent coaching at 6 and 10 months improves language outcomes at 14 months: a randomized controlled trial. Dev. Sci. 22, e12762 (2019).

Sandbank, M. & Yoder, P. J. The association between parental mean length of utterance and language outcomes in children with disabilities: a correlational meta-analysis. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 25, 240–251 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Katherine E. Travis, Sarah E. Dubner, and Lisa Bruckert for their generous contributions to the discussions of the issues. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health RO1- HD069150 and a Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute Postdoctoral Support Award to Janet Bang.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the review. HF, AA, and JB reviewed all articles. HF and JB drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to revisions and approved the final version of the manuscript. Each author has met the Pediatric Research authorship requirements.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bang, J.Y., Adiao, A.S., Marchman, V.A. et al. Language nutrition for language health in children with disorders: a scoping review. Pediatr Res 87, 300–308 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0551-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0551-0