Abstract

Cysteinyl leukotrienes (cysLTs) facilitate eosinophilic mucosal type 2 immunopathology, especially in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), by incompletely understood mechanisms. We now demonstrate that platelets, activated through the type 2 cysLT receptor (CysLT2R), cause IL-33-dependent immunopathology through a rapidly inducible mechanism requiring the actions of high mobility box 1 (HMGB1) and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). Leukotriene C4 (LTC4) induces surface HMGB1 expression by mouse platelets in a CysLT2R-dependent manner. Blockade of RAGE and neutralization of HMGB1 prevent LTC4-induced platelet activation. Challenges of AERD-like Ptges−/− mice with inhaled lysine aspirin (Lys-ASA) elicit LTC4 synthesis and cause rapid intrapulmonary recruitment of platelets with adherent granulocytes, along with platelet- and CysLT2R-mediated increases in lung IL-33, IL-5, IL-13, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid HMGB1. The intrapulmonary administration of exogenous LTC4 mimics these effects. Platelet depletion, HMGB1 neutralization, and pharmacologic blockade of RAGE eliminate all manifestations of Lys-ASA challenges, including increase in IL-33, mast cell activation, and changes in airway resistance. Thus, CysLT2R signaling on platelets prominently utilizes RAGE/HMGB1 as a link to downstream type 2 respiratory immunopathology and IL-33-dependent mast cell activation typical of AERD. Antagonists of HMGB1 or RAGE may be useful to treat AERD and other disorders associated with type 2 immunopathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 immunity is beneficial for mucosal defense against helminths,1 epithelial repair following parasitic or respiratory viral infections,2,3 and metabolic homeostasis.4 It also drives eosinophil-rich (type 2) immunopathology that contributes substantially to the pathogenesis of asthma,5 chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS),6 and allergic esophagitis.7 Pathogens and allergens that carry danger signals (e.g., glycans, endotoxin, fungal, or helminthic proteases) initiate type 2 immunity by activating or damaging barrier cells at mucosal surfaces. Barrier cells generate and release the cytokines IL-33, IL-25, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)8 that directly stimulate innate resident tissue effector cells bearing their receptors (e.g., mast cells (MCs), macrophages, group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s)). These effector cells then release IL-5, IL-13, and other products that promote the recruitment and activation of eosinophils and basophils and induce mucous production,9,10,11 as well as amphiregulin that facilitates barrier repair.3 Barrier-derived cytokines also facilitate durable type 2 adaptive immune responses through their effects on dendritic cells (DCs)12 and conventional T helper cells11,13 to sustain eosinophilic inflammation and induce IgE production.8 Whether innate or adaptive type 2 responses benefit the host or cause disease depends on the duration and nature (e.g., infectious vs. non-infectious) of the initiating stimulus, as well as the extent to which these responses are sustained and amplified by endogenous danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), some of which are provided by infiltrating hematopoietic cells.

High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a chromatin-binding protein that functions as a DAMP when released from damaged epithelial cells,14 or by activated macrophages.15 HMGB1 is a promiscuous ligand, acting at several toll-like receptors (TLRs)16 and at the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE).17,18 HMGB1 amplifies the sterile inflammation associated with thrombosis,19 acute lung injury, and sepsis.20 RAGE mediates most effects of HMGB1 on lung tissue,14,21 neutrophils,18 and endothelial cells.17 Platelets store HMGB1, mobilize it to the cell surface when activated, and then release it into microparticles.22 Platelets can also bind HMGB1 through both RAGE23 and TLR4,24 consistent with potential autocrine actions.25 Recent studies demonstrate that HMGB1 and RAGE play major roles in mouse models of type 2 lung immunopathology.14 HMGB1 signaling through both TLR4 and RAGE is essential for immunologic sensitization of mice to inhale dust mite allergens.14 RAGE expression by resident lung tissue cells is critical for induced airway eosinophilia, upregulation of IL-33 expression, expansion of ILC2s, and production of IL-5 and IL-13 in a model of eosinophilic airway inflammation induced by repetitive intrapulmonary administrations of dust mite allergens or Alternaria.21 HMGB1 levels in the sputum from patients with severe asthma26 and the expressions of HMGB1 and RAGE in nasal tissue from patients with eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP)27,28 exceed those from controls with less severe disease, suggesting relevance of HMGB1 and RAGE to human respiratory diseases driven by type 2 immunopathology. However, the relevant cell sources and mechanisms responsible are incompletely characterized.

Cysteinyl leukotrienes (cysLTs) are potent lipid inflammatory mediators generated from arachidonic acid by eosinophils, MCs, basophils, and myeloid DCs through the sequential actions of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) and leukotriene C4 synthase (LTC4S). Platelets lack 5-LO, but express LTC4S and convert LTA4 from adherent granulocytes to the parent cysLT, LTC4.29 LTC4 is released and converted extracellularly to the potent bronchoconstrictor LTD4, and then to the stable, abundant metabolite LTE4. All three cysLTs are active in vivo, binding to the types 1, 2, and 3 cysLT receptors (termed CysLT1R, CysLT2R, and CysLT3R/GPR99, respectively).30,31,32 The short-lived nature of LTC4 suggests that it may function in a rapid and autocrine manner in vivo. CysLTs are strongly associated with asthma and CRSwNP.33 In humans, this association is best exemplified by aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), in which idiosyncratic cysLT- and MC-driven reactions to aspirin and other nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors are pathognomonic. AERD involves severe CRSwNP, eosinophilic asthma, dysregulated steady-state cysLT production, and aberrant platelet activation.34,35 In a model of AERD using mice lacking the inducible form of prostaglandin E2 synthase (Ptges−/− mice), inhaled lysine aspirin (Lys-ASA) induces a surge in LTC4 synthesis, lung MC activation, and resultant changes in lung function. All of these features require platelets and adherent granulocytes, but the responsible platelet-associated functions are unclear.36 We now demonstrate that CysLT2R-dependent release of HMGB1 from platelets during such aspirin challenges elicits RAGE-dependent autocrine platelet activation and the release of platelet-associated IL-33. These platelet-dependent increases in IL-33 drive MC activation and changes in lung function, as well as rapid increases in the productions of IL-5 and IL-13. Thus, platelet IL-33 is a rapidly inducible and physiologically relevant effector of a CysLT2R/HMGB1/RAGE-dependent pathway that could be a target for therapy of AERD, asthma, and CRS.

Results

HMGB1 amplifies LTC4-induced platelet activation by RAGE-mediated autocrine mechanism

LTC4 elicits expression of surface CD62P, the release of chemokines, and synthesis of TXA2 by murine platelets exclusively through CysLT2R.37 To determine whether CysLT2R-mediated activation also mobilizes HMGB1 to the platelet surface (a prerequisite for its release into microparticles22), we monitored surface expression of HMGB1 by flow cytometry on CD41+ platelets in platelet-rich plasma (PRP) stimulated ex vivo. We compared the activity of cysLTs (250 nM each) with that of thrombin (0.5 U/ml), a classical agonist for platelet aggregation. WT platelets stimulated in PRP with LTC4, but not with LTD4 or LTE4, displayed membrane-bound HMGB1 in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1a, left).22 LTC4-mediated induction of surface CD62P expression followed a similar time course (Fig. 1a, right). Stimulation of the PRP with thrombin elicited platelet surface HMGB1 and CD62P expression more rapidly than LTC4 (peaking by 10 min) (Fig. 1b) followed by the anticipated clot formation. LTC4-stimulated PRP did not clot, even with prolonged (1 h) incubation. LTC4 failed to induce the surface expression of either HMGB1 or CD62P on platelets lacking CysLT2R (Fig. 1c). LTC4 also induced modest surface expression of HMGB1 by platelets from healthy human volunteers in a dose-dependent manner, peaking at 1 nM LTC4 (increased from 7.4 ± 3.1% to 13.8 ± 3.4% HMGB1+ platelets, n = 6, P = 0.04, data not shown).

Induction of HMGB1 surface expression by platelets in response to exogenous and endogenous LTC4. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was obtained from the indicated mouse strains and stimulated with various agonists. The CD41+ platelet gate was analyzed by flow cytometry with Abs specific for HMGB1 (left panels) or CD62P (right panels) along with corresponding isotype controls. a Time-dependent inductions of surface HMGB1 and CD62P by LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4 at the indicated concentrations. b Comparison of LTC4 versus thrombin stimulation for surface expressions of HMGB1 and CD62P. c Effect of Cysltr2 deletion on LTC4-induced HMGB1 and CD62P expression by platelets. d Induction of HMGB1 and CD62P expression by platelet-derived LTC4 converted from exogenous LTA4. Results in a–d are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments that included a minimum of three mice per group

Platelets adhere avidly to granulocytes in asthma and AERD.34,35,38 When adherent to granulocytes, platelets can convert granulocyte 5-LO-derived LTA4 to LTC4 via platelet-intrinsic LTC4S.39 To determine whether LTC4 generated by platelet-intrinsic LTC4S, like exogenous LTC4, could elicit CysLT2R-dependent HMGB1 release, we provided platelets in PRP from WT, Ltc4s−/−, and Cysltr2−/− mice with exogenous LTA4. LTA4 induced surface expressions of both CD62P and HMGB1 by WT platelets, both of which were abolished in platelets lacking LTC4S and platelets lacking CysLT2R. In contrast, exogenous LTC4 induced HMGB1 and CD62P surface expressions by Ltc4s−/− platelets, but not by Cysltr2−/− platelets (Fig. 1d).

To determine whether platelet-derived HMGB1 amplified LTC4-induced platelet activation by signaling in an autocrine manner, we monitored surface expressions of CD62P (and HMGB1) on WT platelets that were pre-treated for 15 min with the selective RAGE antagonist FPS-ZM140 or with the selective TLR4 antagonist LPS-RS41 prior to stimulation with LTC4 across a range of doses. FPS-ZM-1 (1 µM) potently inhibited the expressions of both CD62P and HMGB1 induced by all active doses of LTC4 (Fig. 2a), and also inhibited these responses to the lowest active LTC4 dose tested (50 nM) when provided at 0.1 µM. LPS-RS (10 µg/ml) failed to alter expressions of either CD62P or HMGB1 induced by any dose of LTC4 tested. In contrast, treatment with LPS-RS, but not with FPS-ZM1, suppressed thrombin-induced expressions of CD62P and HMGB1 (Fig. 2b). LTC4 also induced the release of CXCL7 and the production of thromboxane (TX)A2 (as reflected by detection of the stable metabolite TXB2) by platelets. These responses were blocked by FPS-ZM-1 (1 µM), but not by LPS-RS (Fig. 2c). Conversely, thrombin-induced release of CXCL7 and TXA2 production were blocked by LPS-RS, but not by FPS-ZM-1. Additionally, LTA4-induced expressions of CD62P and HMGB1 (reflecting the effects of platelet-converted LTC4) were blocked by the FPS-ZM-1 (1 µM), but not by LPS-RS (Fig. 2d). Pre-treatment of WT platelets with a neutralizing anti-HMGB1 antibody blocked the expression of CD62P (Supplementary Fig. 1A) and the release of mediators (Supplementary Fig. 1B) induced by LTC4 or LTA4, but did not alter thrombin-induced platelet activation.

Effects of RAGE or TLR4 blockade on LTC4-induced platelet activation. Platelet- rich plasma (PRP) was obtained from the indicated mouse strains and stimulated with LTC4 at the indicated concentrations or with thrombin (0.5 U/ml). Some samples were treated with the selective RAGE antagonist FPS-ZM1, and others with the TLR4 antagonist LPS-RS at the indicated doses prior to stimulation. a Effects of RAGE blockade on LTC4-induced surface expression of HMGB1 (left) and CD62P (right) by CD41+ platelets stimulated for 30 min. b Effects of RAGE and TLR4 blockade on expression of HMGB1 (left) and CD62P (right) by platelets in PRP stimulated for 30 min by LTC4 or thrombin. c Concentrations of CXCL7 (left) and TXB2 (right) detected by ELISA in the supernatants from PRP stimulated as in b. d Effects of RAGE and TLR4 antagonists on surface expression of HMGB1 (left) and CD62P (right) by platelets in PRP stimulated by LTA4 (to elicit conversion by platelet LTC4S) or LTC4 at the indicated doses. Results in a–d are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments that included a minimum of three mice per group

Murine aspirin sensitivity involves a platelet and cysLT-driven autocrine loop that depends on CysLT2R, HMGB1, and RAGE

To determine whether cysLT-elicited HMGB1 and RAGE signaling were important for a platelet-dependent pulmonary physiologic response in vivo, we performed Lys-ASA-challenges in AERD-like Ptges−/− mice using a standard protocol and measured airway resistance (RL).36 Due to their inability to maintain bronchoprotecitve levels of PGE2, Ptges−/− mice exhibit sharp increases in airway resistance (RL) in response to Lys-ASA inhalation challenges that are accompanied by activation of lung MCs and that depend on endogenous cysLTs and platelet-adherent granulocytes.36 After six doses of intranasal Df to establish airway inflammation, Ptges−/− mice were mechanically ventilated and challenged with aerosolized Lys-ASA. Changes in RL and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid mediators were monitored. On the day prior to challenge, some mice received a single intraperitoneal dose of a neutralizing anti-HMGB1 antibody or an IgG control. Other mice were treated with FPS-ZM1 to block RAGE, with HAMI-3379, a CysLT2R selective antagonist,42 or with corresponding vehicle controls. As expected, inhalation challenges with Lys-ASA sharply increased RL in Df-primed Ptges−/− mice (Fig. 3a), accompanied by significant increases in BAL fluid levels of HMGB1 (Fig. 3b) and cysLTs (Fig. 3c). Additionally, the levels of the platelet activation marker CXCL7 (Fig. 3d) and the MC activation markers mouse MC protease 1 (mMCP-1) (Fig. 3e), histamine (Fig. 3f), and PGD2 (Fig. 3g) all increased in response to Lys-ASA. Neutralization of HMGB1, RAGE blockade with FPS-ZM1, and CysLT2R blockade with HAMI-3379 all prevented the increase in RL, while preventing the increase in all BAL fluid mediators, including CXCL7 and HMGB1 (Fig. 3a–g) compared with corresponding isotype or vehicle controls.

Effects of RAGE blockade, HMGB1 neutralization, and CysLT2R antagonism on physiologic response of AERD-like Ptges−/− mice to Lys-ASA inhalation challenge. Df-primed Ptges−/− mice were treated with the indicated Abs, antagonists, or corresponding isotype and vehicle controls. Twenty-four hours later, mice were anaesthetized, sedated, mechanically ventilated, and challenged by aerosoled Lys-ASA or PBS control. a Maximum change in RL for the indicate groups of mice monitored for 45 min after Lys-ASA challenge. b Levels of HMGB1 collected in BAL fluids from the same mice as in a. c Levels of cysLTs in the BAL fluids. d Levels of CXCL7 in BAL fluids. e Levels of MMCP-1, f histamine and g PGD2 in the BAL fluids from the same mice as in a–d. Results are mean ± SEM from two independent experiments using a total of 10 mice in each group

Platelets activated via CysLT2R and HMGB1/RAGE control rapid increases in lung IL-33

We next sought to identify potential mechanisms by which CysLT2R/HMGB1/RAGE-dependent platelet activation drive physiologic changes in the lung. To determine whether platelets were recruited to the lung during Lys-ASA challenge, we performed immunohistochemistry for CD41 on the lungs of Df-primed Ptges−/− mice collected 45 min after the administration of PBS or Lys-ASA. We also monitored the quantity of CD41 and CD61 proteins in lung lysates as a surrogate for infiltrating platelets. Lungs of Df-primed, PBS-challenged Ptges−/− mice contained few CD41+ free platelets scattered in the alveolar septae (Fig. 4a, second panel). Compared with the PBS-challenged controls, CD41+ platelets, some of which appeared in aggregates with leukocytes, increased markedly in lungs of Lys-ASA challenged mice, particularly around bronchovascular bundles with leukocyte accumulation (Fig. 4a, third panel). The increase in airway-associated platelets in response to Lys-ASA inhalation challenge was paralleled by an increase in immunoreactive CD41 (not shown) and CD61 identified in western blots of whole lung lysates (Fig. 4b). Depletion of platelets prevented the increase in BAL fluid HMGB1 observed in the Lys-ASA-challenged mice without altering the baseline observed in the PBS-challenged controls (Fig. 4c). Immunohistology for CD41 and western blotting for CD61 verified successful platelet depletion (Fig. 4a, b). Depletion of platelets with anti-CD41 prevented the Lys-ASA induced increase in RL (Supplementary Fig. 2A) and BAL fluid cysLTs and MC activation markers (Supplementary Fig. 2B) as in our previous study36 and eliminated the increase in BAL fluid CXCL7 (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Blood platelet counts were unaffected by HAMI-3379 and FPS-ZM1, whereas anti-HMGB1 decreased blood platelets by ~70% (not shown).

Recruited platelets account for the Lys-ASA-induced increment in HMGB1. Lungs were collected from PBS- or Lys-ASA-challenged Ptges−/− mice treated with a platelet-depleting anti-CD41 Ab or isotype control. a The lung sections were stained with anti-CD41 mAb or an isotype control. Infiltrating platelets are identified by the red staining. b Western blotting of lung lysates from Ptges−/− mice of the indicated treatment groups for CD61 as a surrogate marker for recuited platelets. A blot from a representative individual experiment (top) and quantitative densitometry from two separate experiments (bottom) are shown. c BAL fluid levels of HMGB1 from mice challenged with Lys-ASA or PBS after treatment with anti-CD41 or isotype. Results in a are from single mice representative of at least five per group in three different experiments. Results in c are mean ± SEM from at least 10 mice per group from two separate experiments

Because IL-33 is a proximal inducer of MC activation and MC-dependent changes in RL in Lys-ASA-challenged Ptges−/− mice,43 we sought to determine whether recruited platelets were an important source of IL-33 in this model, and if so, whether platelet-derived IL-33 required the cysLT-driven activation circuit involving HMGB1 and RAGE. We examined lysates of lungs from saline and Lys-ASA-challenged mice for total IL-33 protein. Remarkably, Lys-ASA challenge of the Ptges−/− mice increased total lung levels of IL-33 by ~2.5-fold compared with vehicle-challenged controls 45 min after the challenges (Fig. 5a). Depletion of platelets eliminated the rapid Lys-ASA-induced increases in lung IL-33 protein (Fig. 5a). Treatment of the mice with HAMI-3379 to block CysLT2R, with FPS-ZM1 to block RAGE, or with anti-HMGB1 also all prevented the rapid Lys-ASA-induced increases in total lung IL-33 (Fig. 5b). None of the interventions altered the baseline levels of IL-33 observed in PBS-challenged controls. To determine whether the platelet-dependent increment in IL-33 induced the production of downstream type 2 cytokines, we examined the lung lysates for the presence of IL-5 and IL-13. Both cytokines rapidly increased in parallel with IL-33 (Fig. 5a). The increases in IL-5 and IL-13 were eliminated by platelet depletion (Fig. 5a) and by blockade of the CysLT2R/HMGB1/RAGE pathway (Fig. 5b). Western blotting identified full-length IL-33 protein in platelets (Fig. 5c). Stimulation of washed platelets ex vivo with LTC4 or calcium ionophore for 30 min induced their release of IL-33 protein into the supernatants while decreasing the content of platelet-associated IL-33, as did sodium azide to induce necrosis (Fig. 5c, left panel). Blockades of RAGE or CysLT2R prevented the release of IL-33 in response to LTC4 (Fig. 5c, right panel). Similar results were obtained with platelets from Ptges−/− mice (not shown).

Rapid platelet-dependent increase in lung IL-33 induced by Lys-ASA challenge. Df-primed Ptges−/− mice were treated with the indicated Abs, antagonists, or corresponding isotype and vehicle controls. a Levels of IL-33 (left), IL-5 (middle), and IL-13 (right) proteins detected in homogenates of lungs from the indicated groups of Ptges−/− mice with and without platelet depletion collected 45 min after PBS- or Lys-ASA challenge. b Effects of treatment with the indicated Abs and antagonists on Lys-ASA-induced increases in IL-33, IL-5, and IL-13 detected in lysates of lungs from Ptges−/− mice. c Western blotting for IL-33 protein in supernatants and pellets of washed platelets from naive WT mice subjected to the indicated stimuli for 1 h. Results in a and b are mean ± SEM from at least 10 mice per group from two separate experiments. Results in c are representative of three different experiments. Results from experiments using Ptges−/− platelets yielded similar results

Exogenous LTC4 rapidly induces platelet-dependent increases in IL-33 and lung type 2 cytokine generation

Intranasal administration of LTC4 to ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized WT mice prior to inhalation challenge with low dose OVA markedly increases the numbers of eosinophils in the lung 24 h after last challenge.37 This increase requires CysLT2R-dependent platelet activation,44 and is also associated a CysLT2R-mediated increase in lung IL-33 that localizes primarily to AT2 cells.45 We sought to determine whether platelets also contributed to the CysLT2R-dependent IL-33 expression and downstream immunopathology in this model. We administered intranasal LTC4 to OVA-sensitized WT mice 12 h prior to each of three low dose OVA challenges on successive days. These mice were euthanized 24 h after the final dose of OVA (and 36 h after the final dose of LTC4). Due to the short half-lives of platelets, we examined some mice 1 h after a fourth dose of LTC4 compared with a vehicle control. Compared with the mice treated with OVA alone, mice treated with three doses of LTC4 exhibited sharp increases in BAL fluid total cells and eosinophils as anticipated (Fig. 6a). Three doses of LTC4 also increased the BAL fluid levels of HMGB1, CXCL7, and TXB2(Fig. 6b), as well as levels of IL-33 (Fig. 6c), IL-5, and IL-13 (Fig. 6d) in lung homogenates, and the numbers of lung ILC2s (Fig. 6e) compared with buffer control-treated mice as reported previously. The administration of an additional dose of LTC4 induced modest but significant additional increases in total cells, total eosinophils, platelet activation markers, HMGB1, IL-33, IL-5, and IL-13 within 1 h. Depletion of platelets immediately before the additional dose of LTC4 eliminated these increases (Fig. 6a–d), without altering the increments induced by the first three LTC4 doses or altering the numbers of ILC2s (Fig. 6e). Western blots of whole lung lysates revealed a significant increment in lung CD61 levels induced by the additional dose of LTC4 and confirmed successful platelet depletion using anti-CD41 (Fig. 6f).

Exogenously administered LTC4 induces a rapid platelet-dependent increase in lung IL-33 and type 2 cytokine production. OVA-sensitized WT mice received three aerosol challenges with 0.1% OVA. Some mice received intranasal administration of LTC4 (2.2 nmol) preceding each OVA challenge by 12 h. The indicated mice were then treated with a platelet-depleting anti-CD41 Ab or isotype one day before receiving either an additional intranasal dose of LTC4 or PBS control 1 h before euthanasia. a BAL fluid total cells (left) and eosinophils (right). b BAL fluid levels of HMGB1 (top row), CXCL7 and TXB2 (middle row) from the same mice as in a. c Levels of IL-33 protein detected in homogenates from the lungs of mice in the indicated groups. d Levels of IL-5 and IL-13 from the same homogenates as in c. e Numbers of ILC2s detected in single cell suspensions from the same mice. f Western blots of whole lung lysates showing changes in CD61 as a surrogate for platelet recruitment. Results in a–e are from 10 mice per group from two independent experiments. Results in f are from a representative blot (left), with quantitative densitometry (right) from five mice per group

LTC4 elicits IL-33 release from nasal polyp tissue

To determine whether cysLTs can elicit IL-33 release in inflamed human respiratory tissue, we subjected surgically excised human nasal polyp tissue to ex vivo stimulation with LTC4. Tissue was divided into fragments of equivalent weight and incubated in the presence of LTC4 or an equal volume of buffer control (ethanol diluted in PBS) for 1 h. The quantities of IL-33 was measured in the supernatants. LTC4 induced significant release of IL-33 from the polyp tissue above the buffer control (Supplementary Fig. 3). LTC4 also tended to increase the release of HMGB1 from the same tissue samples (from 1250 ± 325 to 1446 ± 302 pg/ml, mean ± SEM, n = 7, not shown), although this did not reach significance (P = 0.20).

Discussion

In addition to their essential role in hemostasis, platelets can amplify type 2 respiratory immunopathology.46 Blood and sinonasal tissues of patients with AERD contain especially large numbers of platelet-adherent eosinophils and activated free platelets.35 Both platelet-adherent eosinophils38 and activated free platelets are rapidly recruited to the lungs of atopic asthmatic human subjects in response to allergen inhalation challenge.47 Extravasated platelets are found in bronchial tissues of patients with asthma.48 In allergen-sensitized mice, free platelets and platelet-adherent leukocytes are recruited to the lungs in response to inhalation challenges,49 and depletion of platelets markedly suppresses the induction of type 2 immunopathology in the lung.44 Implicated mechanisms for the role of platelets in lung type 2 inflammation include CD62P-dependent priming of eosinophil integrin avidity,38 TXA2-dependent priming of endothelial adhesion pathways,44 transcellular synthesis of LTC4 by platelet-intrinsic LTC4S,35 and induction of Th2 cytokine production by CD4+ T cells through the Wnt pathway inhibitor Dickkopf-1.50 Activated platelets can mobilize HMGB1 from cytosolic stores to the plasma membrane and subsequently release it into microparticles.22,51 HMGB1/RAGE signaling promotes induced lung expression of IL-33 and expansion of ILC2s in allergen-challenged mice,14 and has been linked to severe CRS,52 asthma26,53, and AERD28 in humans, but has never been attributed specifically to platelets in type 2 immunopathology. Platelets, cysLTs, and IL-33 are all implicated in AERD,35,44 and all are essential to the AERD-like responses of Ptges−/− mice to Lys-ASA challenge.36,43,45 Given that platelets are potential sources of both HMGB1 and cysLTs, as well as effectors of cysLT functions, we sought to determine whether HMGB1 and RAGE served as intermediaries of platelet functions in models of AERD and type 2 immunopathology.

We first determined that stimulation with LTC4 upregulates surface expression of HMGB1 by WT platelets ex vivo, in parallel with CD62P (Fig. 1a, b).29 As with CD62P, the LTC4-induced expression of surface HMGB1 depended on CysLT2R (Fig. 1c). The fact that exogenous LTA4 induced platelet CD62P and HMGB1 membrane expression that was absent in both Ltc4s−/− and Cysltr2−/− platelets confirms that platelet-derived LTC4 can activate an autocrine circuit that leads to HMGB1 surface expression (Fig. 1d). The fact that blockade of RAGE (Fig. 2) or neutralization of HMGB1 (Supplementary Fig. 1) suppressed LTA4- and LTC4-induced CD62P and HMGB1 surface expression, as well as TXA2 synthesis and CXCL7 release, implies that HMGB1 can signal through RAGE to amplify CysLT2R-mediated platelet activation in response to either exogenous or endogenous LTC4. Although it is possible that the neutralizing antibodies may block epitopes of HMGB1 needed for cell surface or ELISA detection, all of the effects of antibody blockade are mirrored by FPS-ZM1, strongly supporting the thesis. Notably, granulocytes that are capable of generating LTC4 without platelet “help” due to their endogenous LTC4S expression (eosinophils and basophils) show substantially higher frequencies of adherent platelets in the blood of subjects with AERD than do neutrophils in the same samples.34,35 Thus, eosinophil or basophil-derived LTC4 may also elicit CysLT2R-dependent platelet activation and HMGB1 release that does not require transcellular LTC4 synthesis. Although RAGE can bind ligands other than HMGB1, our findings with blocking antibodies suggest that platelet HMGB1 can elicit cellular responses in an autocrine (RAGE-dependent) manner and likely a paracrine manner on adjacent cells.

We used an AERD model to determine the potential physiologic relevance of HMGB1 and RAGE as effectors of platelet-driven physiologic responses in the respiratory tract. Compared with PGE2-sufficient WT controls, Ptges−/− mice display dysregulated steady-state cysLT production, marked type 2 immunopathology, and sharp increases in platelet-adherent granulocytes in the blood and lung tissue after priming with Df.36 After establishing inflammation, Ptges−/− mice also display a rapid increase in RL and release of mediators (including large quantities of cysLTs) reflecting MC activation in response to challenges with nonselective COX inhibitors. In this model, steady-state CysLT2R signaling promotes alveolar type 2 cell IL-33 expression during priming with Df, and CysLT1R expands ILC2s and facilitates their cytokine generation.54 During Lys-ASA-induced reactions, CysLT3R/GPR99 and CysLT1R facilitate changes in airway resistance directly induced by their cognate ligands (LTE4 and LTD4, respectively) generated by MCs after their activation.36 The fact that all features of responses to Lys-ASA are abolished when by platelet and granulocyte depletions or CysLT2R blockade36,43,45 are performed immediately prior to Lys-ASA (and after inflammation is established), however, implies an additional proximal step requiring platelet-adherent granulocytes and a CysLT2R signaling event to promote the downstream processes. Our studies clearly implicate HMGB1/RAGE in the physiological and biochemical responses to aspirin in this model (Fig. 3a–g), including the release of mediators from both platelets (Fig. 3d) and MCs (Fig. 3e–g). These observations prompted us to seek an effector that might link upstream platelet LTC4/HMGB1/RAGE to downstream MC activation in this model.

IL-33, a potent inducer of innate type 2 immunity and MC activation, abounds in nasal polyp tissue, especially from patients with AERD.43 IL-33 is necessary for the cysLT-driven MC activation induced by Lys-ASA challenge of Ptges−/− mice based on experiments using blocking antibodies and a recombinant soluble receptor.43 Although both Df-primed Ptges−/− mice and LTC4-treated OVA-challenged WT mice display substantial CysLT2R-dependent IL-33 expression in the nuclei of AT2 cells, several lines of evidence indicate that platelets activated through CysLT2R/HMGB1/RAGE signaling provide an increment in IL-33 required to elicit the physiologic response to Lys-ASA, as well as the eosinophilic pathology elicited by exogenous LTC4. First, Lys-ASA challenges rapidly recruited platelets to the lung (Fig. 4a, b). Second, Lys-ASA challenges rapidly increase total lung IL-33 protein and the downstream ILC2/Th2-derived cytokines IL-5 and IL-13, all of which were ablated by depletion of platelets (Fig. 5a) or blockades of CysLT2R, HMGB1 and RAGE (Fig. 5b). Third, direct challenges of mice with exogenous LTC4 also produce rapid, platelet-dependent increases in total lung IL-33 (Fig. 6c), IL-5, and IL-13 (Fig. 6d), which also depend on platelets, CysLT2R, HMGB1, and RAGE. Fourth, platelets express full-length IL-33 protein, as previously reported55 and released it in response to stimulation with LTC4 or with calcium ionophore (Fig. 5c), as well as sodium azide to elicit necrosis. The ex vivo release of IL-33 in response to LTC4 was also abolished by blockade of CysLT2R or RAGE. In contrast to barrier cells, where full-length IL-33 is tightly bound to chromatin and released principally during necrosis,56 megakaryocytes and platelets store IL-33 in their cytosol.55 The absence of chromatin in platelets may facilitate compartmentalized IL-33 release from these cytosolic stores when they are activated. CysLT2R-driven platelet activation on the surface of eosinophils and other granulocytes in the endovascular space, amplified by HMGB1/RAGE, may facilitate TXA2-dependent endothelial VCAM-1 induction that permits recruitment of the platelet-adherent granulocyte pool to the lung.44 This cell population may provide a dynamic, abundant CysLT2R-driven pool of IL-33 that can be rapidly mobilized to the lung. This may explain why the physiologic responses to Lys-ASA and MC activation in this model depend on platelets, granulocytes, cysLTs, and IL-33. The fact that LTC4 can drive release of IL-33 from nasal polyp tissue (Supplementary Fig. 3) suggests that the putative pathway is relevant to human disease, although the specific cells responsible for IL-33 (and HMGB1) release in this complex tissue may include both platelet and non-platelet (e.g., epithelial and endothelial) sources.57

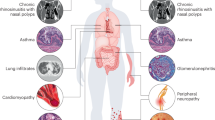

Combined with previous studies, our findings reveal that the three receptors for cysLTs act at temporally and spatially distinct steps in type 2 immunity and reactions to aspirin. “Unbraking” of granulocyte 5-LO by aspirin-induced depletion of PGE2 may promote LTA4 synthesis in the intravascular compartment.35,36 After conversion, the resultant LTC4 triggers an “alarm” through CysLT2R, inducing HMGB1/RAGE signaling, endothelial activation, and rapid recruitment of platelet-adherent granulocytes to the airway tissue. The recruitment of platelet-adherent granulocytes mobilizes a pool of IL-33 to the lung that serves as a requisite ligand to activate MCs, resulting in a “surge” of LTC4 generation within the airway along with release of histamine, proteases, PGD2 and other potent mediators.43 The conversion of MC-derived LTC4 to LTD4 and LTE4 leads to additional cysLT-driven events that require CysLT1R (airway smooth muscle constriction (in humans),58 resident ILC2 activation59) and CysLT3R/GPR99 (mucous secretion60 and IL-25 release from brush cells61) (Fig. 7). This hypothetical sequence potentially reconciles several clinical observations in AERD, including the aberrantly high numbers of platelet-adherent granulocytes in the blood and tissue,34,35 the high levels of baseline tissue cysLTs and IL-33,43 and the demonstration that MC activation in AERD both requires62 and induces63 synthesis of cysLTs. The proximal nature of CysLT2R signaling in this sequence suggests that drugs targeting CysLT2R could have broad effects in contexts where type 2 immunopathology and cysLT production are prominent.

Schematic showing putative initiating (CysLT2R-dependent) and downstream (CysLT1R and CysLT3R) dependent effects of cysLTs in driving the mechanism responsible for reactions to aspirin. Platelet CysLT2R is essential to initiate HMGB1/RAGE signaling that permits platelet activation and conjugation to granulocytes. Platelets adherent to granulocytes and activated via CysLT2R/HMGB1/RAGE provide a pool of IL-33 that drives MC activation and a secondary surge of cysLTs to act at cognate receptors, and also activates ILC2s to promote additional type 2 immunopathology

Methods

Reagents

Df was obtained from Greer Laboratories (XPB81D3A25; Lenoir, NC, USA). Ovalbumin and PBS were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The mMCP-1 EIA kit was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Thrombin, FPS-ZM1, HAMI-3379, puromycin, LTA4, LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4 were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Histamine, TXB2, PGD2, and cysLT EIA kits were from Cayman. IL-5, IL-13, IL-33, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 EIA kits were from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). CXCL7 EIA kit was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). The HMGB1 EIA kit was from LifeSpan (Providence, RI, USA). The following antibody reagents were purchased from the indicated vendors: endotoxin-free monoclonal rat anti-mouse CD41 (Biolegend), monoclonal rat anti-mouse IL-33, monoclonal rat anti-mouse CD41 (R&D), and polyclonal goat anti-mouse/human/rat GAPDH (R&D systems) donkey anti-goat IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor® 488 (Invitrogen), donkey anti-rabbit IgG(H + L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor® 594 (Invitrogen), DAKO serum-free protein block (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), DAKO target retrieval (Agilent). FITC anti-mouse CD11c, FITC anti-mouse/human CD11b, FITC anti-mouse IgE, FITC anti-mouse CD3ε, FITC anti-mouse CD19, FITC anti-mouse CD8a, FITC anti-mouse NK-1.1, FITC anti-mouse Ly-6G/Ly-6C (Gr-1), APC anti-mouse CD45, APC/Cy7 anti-mouse/human CD44, PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD90.2, PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse IL-33Rα (IL1RL1, ST2), PE anti-mouse CD278 (ICOS), APC anti-mouse CD41, PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD62P, PE anti-HMGB1, anti-HMGB1, and anti-mouse CD16/32 were all from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Rabbit anti-mouse CD41 mAb ab225896 and the Promark rabbit-on-mouse biopolymer detection system were obtained from Abcam and Biocare Medical, respectively. Rabbit anti-mouse CD61 for western blotting was purchased from Abcam.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice lacking mPGES-1 (Ptges−/− mice) were from Dr. Shizuo Akira (Osaka University, Japan).64 Ltc4s−/− mice65 and Cysltr2−/−66 mice were generated in our insitution. All the mice and wild-type C57BL/6 controls were housed at Center of Comparative Medicine of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA, USA). Six- to 8-week-old male were used. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Protocols 2016N000294 and 2016N000295).

Immunization and challenge

To study potentiation of airway inflammation by exogenous cysLTs, mice were sensitized i.p. on days 0 and 5 with alum-precipitated chicken egg OVA (10 µg). On days 16–18, the mice received intranasal challenge of 2.2 nmol LTC4 or vehicle. On days 17–19, mice were challenged by inhalation of 0.1% OVA. Twenty-four hours after the final OVA aerosol challenge, the mice were euthanized and exsanguinated. The lungs were lavaged three times with 0.7 ml of PBS/5 mM EDTA. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid cells were cytocentrifuged onto slides, stained with Diff-Quick (Fisher Diagnostics, Middletown, VA, USA), and differentially counted.

To study the effect of endogenous cysLTs, airway inflammation was induced in various genotypes by intranasal administration of Df (Greer, 3 µg) as described elsewhere.36 Mice were studied 24 h after the last treatment.

Flow cytometry

Mouse lungs (right lobes) were transferred into six-well dish and tease tissue apart with forceps. Then the tissues were digested at RT for 45 min in 2 ml of dispase (2 U/ml), followed by adding 0.5 mg of DNAse/mouse to the mixture and incubated for 10 min at RT with gently rocking on a shaker to 200 rpm. Cells were filtered through 70-µm nylon meshes and pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 350g at 4 °C. RBC lysis was performed by resuspending the pellet in 2 ml 1x RBC lysis buffer (Biolegend) and incubating on ice for 4 min, terminated by addition of 13 ml of DMEM. Cells were centrifuged for 10 min 350g at 4 °C, and then washed twice with FACS buffer (0.5% BSA in PBS). In total, 1 × 106 cells were stained with antibodies in 100 µl of FACS buffer for 20 min on ice in the dark. The cells were washed and resuspended in 300 µl of 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS prior to analysis on a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). ILC2s were quantitated as Lin-, CD45+ , CD44+ , CD278+ , CD90.2+ cells in the lymphocyte gate. Platelets in PRP were identified based on size and the presence of CD41. The CD62P and HMGB1 + baselines of the CD41+ events were set at 5% for the vehicle control treatment and compared with the agonist treatment (gating strategy for HMGB1 shown in Supplementary Fig. 4). For human samples, healthy volunteer subjects were recruited from the BWH primary care practice for blood donations. The local Institutional Review Board approved the study and all subjects provided written informed consent. PRP was stimulated with LTC4 or an equal volume of ethanol (vehicle control) and processed for flow cytometry for surface HMGB1 on the CD61+ gate using PE-tagged anti-human HMGB1 (Biolegend).

Immunohistochemical staining for CD41

Lungs were fixed in 4% PFA (wt/vol) and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections (5 µm) were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in a graded alcohol series. The sections were then washed in deionized water and boiled in a steamer in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 for 30 min for epitope retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase was inhibited using 0.03% H2O2 in methanol, and slides were equilibrated in PBS. Slides were incubated in either rabbit anti-mouse CD41 mAb (2.5 µg/ml; Abcam ab225896) or isotype control overnight at 4°C. mAb binding was visualized with the Promark micropolymer detection kit (rabbit on mouse-HRP; Biocare Medical) using AEC as the chromogen. Sections were counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin #2 and mounted with VectaMount AQ Aqueous Mounting Medium. Photomicrographs were taken at room temperature on a Leica DM LB2 microscope (Leica 40x objective #506144) fitted with a Nikon DXM 1200 digital camera (0.6 × ). Images were acquired using Nikon ACT-1 version 2.70 software. Images were processed with Origin (OriginLab, Wellesley, MA, USA).

Measurement of airway resistance

Airway resistance (RL) in response to Lys-ASA was assessed with an Invasive Pulmonary Function Device (Buxco, Sharon, CT, USA). Briefly, mice were anesthetized 24 h after the last Df challenge, and a tracheotomy was performed. After allowing for RL to reach a stable baseline, Lys-ASA (12 µl of 100 mg/ml) was delivered to the lung via nebulizer, and RL was recorded for 45 min. The results were expressed as percentage change of RL from baseline.

Cell depletions, antibody blockade, and CysLT2R antagonism

Mice were given i.p. injections with anti-HMGB1 (25 µg/mouse), or endotoxin-free rat anti-mouse CD41 (50 µg/mouse), or equivalent doses of isotype controls on day 18 of the OVA protocol. In the Lys-ASA challenge experiments, mice were given i.p. injections of anti-CD41 (50 µg/mouse), anti-HMGB1 (25 µg/mouse), or FPS-ZM1 (1 mg/kg of body weight) 1 day before the challenge. HAMI-3379 (0.2 mg/kg) or buffer control (ethanol) were given i.p. on 1 and 2 days before the challenge. In some experiments, lung tissue was processed for western blotting as previously described and stained for CD61 to confirm the recruitment of platelets and their depletion from the lung tissue by anti-CD41.

Whole lung cytokine measurements

The lung was harvested and homogenized in tissue protein extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific) with protease inhibitors (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein concentrations of the lysates were measured with BCA protein assay reagent (Thermo Scientific), and lung IL-5/IL-13/IL-33 were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems). The concentration was expressed as pg/mg protein.

Nasal polyp whole tissue stimulation and blood platelet stimulation

Subjects with CRS with nasal polyposis (three with AERD) were recruited from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA, USA) Allergy and Immunology clinics and Otolaryngology clinics. The local Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all subjects provided written informed consent. Subjects with known cystic fibrosis, allergic fungal rhinosinusitis, and unilateral polyps were excluded from the study. Nasal tissue was excised at the time of surgery, and it was placed in RPMI (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin for transport to the laboratory. Within 2 h of surgery, the tissue was removed from RPMI, weighed, and coarsely chopped between two scalpel blades. The tissue fragments were equally divided by weight (10 mg/fragment) and incubated with media alone or 500 nM LTC4 (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) for 60 min, with each condition performed in duplicate. The tissue supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. Data were expressed as the averages for the replicates in each experiment.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as ± SEM from at least 10 mice from at least two experiments, except where otherwise indicated. Analyses were performed with SASTM software. Data were normally distributed, and differences between two treatment groups were assessed using Student's t test, and differences among multiple groups were assessed using one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

References

Fallon, P. G. et al. Identification of an interleukin (IL)-25-dependent cell population that provides IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 at the onset of helminth expulsion. J. Exp. Med 203, 1105–1116 (2006).

Chiaramonte, M. G., Donaldson, D. D., Cheever, A. W. & Wynn, T. A. An IL-13 inhibitor blocks the development of hepatic fibrosis during a T-helper type 2-dominated inflammatory response. J. Clin. Invest 104, 777–785 (1999).

Monticelli, L. A. et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat. Immunol. 12, 1045–1054 (2011).

Dalmas, E. et al. Interleukin-33-activated Islet-resident innate lymphoid cells promote insulin secretion through myeloid cell retinoic acid production. Immunity 47, 928–942 e927 (2017).

Bousquet, J. et al. Eosinophilic inflammation in asthma. N. Engl. J. Med 323, 1033–1039 (1990).

Baba, S. et al. Expression of IL-33 and its receptor ST2 in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Laryngoscope 124, E115–E122 (2014).

Hsu Blatman, K. S., Gonsalves, N., Hirano, I. & Bryce, P. J. Expression of mast cell-associated genes is upregulated in adult eosinophilic esophagitis and responds to steroid or dietary therapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127, 1307–1308 (2011).

Iwasaki, A. & Medzhitov, R. Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat. Immunol. 16, 343–353 (2015).

Neill, D. R. et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2immunity. Nature 464, 1367–1370 (2010).

Huang, Y. et al. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential ‘inflammatory’ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 16, 161–169 (2015).

Guo, L. et al. Innate immunological function of TH2 cells in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 16, 1051–1059 (2015).

Ito, T. et al. TSLP-activated dendritic cells induce an inflammatory T helper type 2 cell response through OX40 ligand. J. Exp. Med 202, 1213–1223 (2005).

Wambre, E. et al. A phenotypically and functionally distinct human TH2 cell subpopulation is associated with allergic disorders. Sci Transl Med 9, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aam9171 (2017).

Ullah, M. A. et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and its ligand high-mobility group box-1 mediate allergic airway sensitization and airway inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134, 440–450 (2014).

Gardella, S. et al. The nuclear protein HMGB1 is secreted by monocytes via a non-classical, vesicle-mediated secretory pathway. EMBO Rep. 3, 995–1001 (2002).

Park, J. S. et al. High mobility group box 1 protein interacts with multiple Toll-like receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C917–C924 (2006).

Treutiger, C. J. et al. High mobility group 1 B-box mediates activation of human endothelium. J. Intern. Med 254, 375–385 (2003).

Huebener, P. et al. The HMGB1/RAGE axis triggers neutrophil-mediated injury amplification following necrosis. J. Clin. Invest 125, 539–550 (2015).

Stark, K. et al. Disulfide HMGB1 derived from platelets coordinates venous thrombosis in mice. Blood 128, 2435–2449 (2016).

Yu, Y., Tang, D. & Kang, R. Oxidative stress-mediated HMGB1 biology. Front Physiol. 6, 93 (2015).

Oczypok, E. A. et al. Pulmonary receptor for advanced glycation end-products promotes asthma pathogenesis through IL-33 and accumulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 136, 747–756 (2015).

Maugeri, N. et al. Circulating platelets as a source of the damage-associated molecular pattern HMGB1 in patients with systemic sclerosis. Autoimmunity 45, 584–587 (2012).

Ahrens, I. et al. HMGB1 binds to activated platelets via the receptor for advanced glycation end products and is present in platelet rich human coronary artery thrombi. Thromb. Haemost. 114, 994–1003 (2015).

Yang, X. et al. HMGB1: a novel protein that induced platelets active and aggregation via Toll-like receptor-4, NF-kappaB and cGMP dependent mechanisms. Diagn. Pathol. 10, 134 (2015).

Vogel, S. et al. Platelet-derived HMGB1 is a critical mediator of thrombosis. J. Clin. Invest 125, 4638–4654 (2015).

Watanabe, T. et al. Increased levels of HMGB-1 and endogenous secretory RAGE in induced sputum from asthmatic patients. Respir. Med 105, 519–525 (2011).

Hong, S. M. et al. Increased expression of high-mobility group protein B1 in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 27, 278–282 (2013).

Dzaman, K., Szczepanski, M. J., Molinska-Glura, M., Krzeski, A. & Zagor, M. Expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products, a target for high mobility group box 1 protein, and its role in chronic recalcitrant rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz.) 63, 223–230 (2015).

Maugeri, N. et al. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte-platelet interaction: role of P-selectin in thromboxane B2 and leukotriene C4 cooperative synthesis. Thromb. Haemost. 72, 450–456 (1994).

Lynch, K. R. et al. Characterization of the human cysteinyl leukotriene CysLT1 receptor. Nature 399, 789–793 (1999).

Heise, C. E. et al. Characterization of the human cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30531–30536 (2000).

Kanaoka, Y., Maekawa, A. & Austen, K. F. Identification of GPR99 protein as a potential third cysteinyl leukotriene receptor with a preference for leukotriene E4 ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10967–10972 (2013).

Kanaoka, Y. & Boyce, J. A. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and their receptors; emerging concepts. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res 6, 288–295 (2014).

Mitsui, C. et al. Platelet activation markers overexpressed specifically in patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., 137, 400–411 (2016).

Laidlaw, T. M. et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene overproduction in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease is driven by platelet-adherent leukocytes. Blood 119, 3790–3798 (2012).

Liu, T., Laidlaw, T. M., Katz, H. R. & Boyce, J. A. Prostaglandin E2 deficiency causes a phenotype of aspirin sensitivity that depends on platelets and cysteinyl leukotrienes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 110, 16987–16992 (2013).

Cummings, H. E. et al. Cutting edge: Leukotriene C4 activates mouse platelets in plasma exclusively through the type 2 cysteinyl leukotriene receptor. J. Immunol. 191, 5807–5810 (2013).

Johansson, M. W. et al. Platelet activation, P-selectin, and eosinophil beta1-integrin activation in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 185, 498–507 (2012).

Murphy, R. C., Maclouf, J. & Henson, P. M. Interaction of platelets and neutrophils in the generation of sulfidopeptide leukotrienes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 314, 91–101 (1991).

Deane, R. et al. A multimodal RAGE-specific inhibitor reduces amyloid beta-mediated brain disorder in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest 122, 1377–1392 (2012).

Tang, A. T. et al. Endothelial TLR4 and the microbiome drive cerebral cavernous malformations. Nature 545, 305–310 (2017).

Yan, D. et al. Differential signaling of cysteinyl leukotrienes and a novel cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 (CysLT(2)) agonist, N-methyl-leukotriene C(4), in calcium reporter and beta arrestin assays. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 270–278 (2011).

Liu, T. et al. Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease involves a cysteinyl leukotriene-driven IL-33-mediated mast cell activation pathway. J. Immunol. 195, 3537–3545 (2015).

Liu, T. et al. Platelet-driven leukotriene C4-mediated airway inflammation in mice is aspirin-sensitive and depends on T prostanoid receptors. J. Immunol. 194, 5061–5068 (2015).

Liu, T. et al. Type 2 cysteinyl leukotriene receptors drive IL-33-dependent type 2 immunopathology and aspirin sensitivity. J. Immunol. 200, 915–927 (2018).

Pitchford, S. C. et al. Platelets are essential for leukocyte recruitment in allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 112, 109–118 (2003).

Averill, F. J., Hubbard, W. C., Proud, D., Gleich, G. J. & Liu, M. C. Platelet activation in the lung after antigen challenge in a model of allergic asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 145, 571–576 (1992).

Beasley, R., Roche, W. R., Roberts, J. A. & Holgate, S. T. Cellular events in the bronchi in mild asthma and after bronchial provocation. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 139, 806–817 (1989).

Pitchford, S. C. et al. Platelet P-selectin is required for pulmonary eosinophil and lymphocyte recruitment in a murine model of allergic inflammation. Blood 105, 2074–2081 (2005).

Chae, W. J. et al. The Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1 promotes pathological type 2 cell-mediated inflammation. Immunity 44, 246–258 (2016).

Rouhiainen, A., Imai, S., Rauvala, H. & Parkkinen, J. Occurrence of amphoterin (HMG1) as an endogenous protein of human platelets that is exported to the cell surface upon platelet activation. Thromb. Haemost. 84, 1087–1094 (2000).

Min, H. J. et al. Level of secreted HMGB1 correlates with severity of inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 125, E225–E230 (2015).

Cuppari, C. et al. Sputum high mobility group box-1 in asthmatic children: a noninvasive sensitive biomarker reflecting disease status. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 115, 103–107 (2015).

Liu, T. et al. Type 2 cysteinyl leukotriene receptors drive IL-33-dependent type 2 immunopathology and aspirin sensitivity. J. Immunol. (Baltim., Md. : 1950) 200, 915–927 (2018).

Takeda, T. et al. Platelets constitutively express IL-33 protein and modulate eosinophilic airway inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., S0091-6749(16)00304-3 [pii];10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.032 (2016).

Lefrancais, E. & Cayrol, C. Mechanisms of IL-33 processing and secretion: differences and similarities between IL-1 family members. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 23, 120–127 (2012).

Ordovas-Montanes, J. et al. Allergic inflammatory memory in human respiratory epithelial progenitor cells. Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0449-8 (2018).

Hamilton, A., Faiferman, I., Stober, P., Watson, R. M. & O’Byrne, P. M. Pranlukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonist, attenuates allergen-induced early- and late-phase bronchoconstriction and airway hyperresponsiveness in asthmatic subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 102, 177–183 (1998).

Doherty, T. A. et al. Lung type 2 innate lymphoid cells express cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1, which regulates TH2 cytokine production. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 132, 205–213 (2013).

Bankova, L. G. et al. Leukotriene E4 elicits respiratory epithelial cell mucin release through the G-protein-coupled receptor, GPR99. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 1605957113 [pii];10.1073/pnas.1605957113 (2016).

Bankova, L. G. et al. The cysteinyl leukotriene 3 receptor regulates expansion of IL-25-producing airway brush cells leading to type 2inflammation. Sci Immunol. 3, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aat9453 (2018).

Fischer, A. R. et al. Direct evidence for a role of the mast cell in the nasal response to aspirin in aspirin-sensitive asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 94, 1046–1056 (1994).

Yoshida, S. et al. Cromolyn sodium prevents bronchoconstriction and urinary LTE4 excretion in aspirin-induced asthma. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 80, 171–176 (1998).

Uematsu, S., Matsumoto, M., Takeda, K. & Akira, S. Lipopolysaccharide-dependent prostaglandin E(2) production is regulated by the glutathione-dependent prostaglandin E(2) synthase gene induced by the Toll-like receptor 4/MyD88/NF-IL6 pathway. J. Immunol. 168, 5811–5816 (2002).

Kanaoka, Y., Maekawa, A., Penrose, J. F., Austen, K. F. & Lam, B. K. Attenuated zymosan-induced peritoneal vascular permeability and IgE-dependent passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in mice lacking leukotriene C4 synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 22608–22613 (2001).

Beller, T. C., Maekawa, A., Friend, D. S., Austen, K. F. & Kanaoka, Y. Targeted gene disruption reveals the role of the cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor in increased vascular permeability and in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46129–46134 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Cirka and H. Raff for technical contributions, and K. Perera and members of the Boyce lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by generous contributions from the Vinik Family, the Kaye Family, and National Institutes of Health Grants AI078908, HL111113, HL117945, R37AI052353, R01AI136041, R01HL136209, R01AI130109, and U19AI095219.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L. designed the experiments and performed them with C.F. and D.G., and analyzed the results with J.A.B. Y.K. developed the compound KO mouse strains. H.R.K. and J.L. did the immunohistochemistry for CD41. J.B. conceived of the study and composed the paper with N.B. and T.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, T., Barrett, N.A., Kanaoka, Y. et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 drives lung immunopathology through a platelet and high mobility box 1-dependent mechanism. Mucosal Immunol 12, 679–690 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41385-019-0134-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41385-019-0134-8

This article is cited by

-

Metabolic alterations upon SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential therapeutic targets against coronavirus infection

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2023)

-

Aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD): molecular and cellular diagnostic & prognostic approaches

Molecular Biology Reports (2021)

-

NSAID-ERD Syndrome: the New Hope from Prevention, Early Diagnosis, and New Therapeutic Targets

Current Allergy and Asthma Reports (2020)