Abstract

An important step to improve outcomes for patients with schizophrenia is to understand treatment patterns in routine practice. The aim of the current study was to describe the long-term management of patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics (APs) in real-world practice. This population-based study included adults with schizophrenia and who had received ≥3 deliveries of an AP from 2012–2017, identified using a National Health Data System. Primary endpoints were real-life prescription patterns, patient characteristics, healthcare utilization, comorbidities and mortality. Of the 456,003 patients included, 96% received oral APs, 17.5% first-generation long-acting injectable APs (LAIs), and 16.1% second generation LAIs. Persistence rates at 24 months after treatment initiation were 23.9% (oral APs), 11.5% (first-generation LAIs) and 20.8% (second-generation LAIs). Median persistence of oral APs, first-generation LAIs and second-generation LAIs was 5.0, 3.3, and 6.1 months, respectively. Overall, 62.1% of patients were administered anxiolytics, 45.7% antidepressants and 28.5% anticonvulsants, these treatments being more frequently prescribed in women and patients aged ≥50 years. Dyslipidemia was the most frequent metabolic comorbidity (16.2%) but lipid monitoring was insufficient (median of one occasion). Metabolic comorbidities were more frequent in women. Standardized patient mortality remained consistently high between 2013 and 2015 (3.3–3.7 times higher than the general French population) with a loss of life expectancy of 17 years for men and 8 years for women. Cancer (20.2%) and cardiovascular diseases (17.2%) were the main causes of mortality, and suicide was responsible for 25.4% of deaths among 18–34-year-olds. These results highlight future priorities for care of schizophrenia patients. The global persistence of APs used in this population was low, whereas rates of psychiatric hospitalization remain high. More focus on specific populations is needed, such as patients aged >50 years to prevent metabolic disturbances and 18–34-year-olds to reduce suicide rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization reports that 20 million people worldwide have schizophrenia [1]. There is a need to improve the care of individuals with schizophrenia, but there is a paucity of recent objective real-world data required to aid the development of concrete strategies for advances in schizophrenia care.

There have been concerted efforts to shift care from the hospital to the outpatient setting to reduce the burden on patients, their relatives and on hospitals [2]. Therefore, it is important to know the proportion of patients with schizophrenia who require psychiatric hospitalization versus adequate ambulatory care. The absence or delay of antipsychotic drugs (APs) treatment and AP withdrawal are primary causes for psychiatric hospitalization [3,4,5,6,7]. Medication observance/compliance is a major issue in all chronic illnesses [8, 9] but is particularly problematic in schizophrenia for various reasons, including poor patient insight into their illness, mental stigma, treatment refusal, lack of effectiveness and adverse events with APs [10, 11]. Systematic reviews have suggested highly variable compliance to APs of 24–90% [12, 13]. Long-acting injectable APs (LAIs) have demonstrated treatment benefits over oral APs in clinical trials and real-world studies of patients with schizophrenia, including reducing relapse or hospitalization risk (by 8–56%) and fewer all-cause discontinuations and withdrawals due to adverse events or lack of efficacy [14,15,16].

Increased suicide risk and comorbid major depressive disorders (MDD) are common in schizophrenia and are frequent causes of hospitalizations [17]. Comorbid MDD (the most common cause of suicide) is present in nearly 50% of patients with schizophrenia, but is poorly screened and treated due to confusion with the negative symptoms of schizophrenia [18].

The long-term use of APs is associated with adverse events, including increased cardiometabolic risk through an unknown mechanism [19]. Cardiovascular disease and cancer are among the most significant drivers of mortality in patients with schizophrenia [20,21,22,23]. Lifestyle and genetic factors may contribute to the increased risk of cardiovascular mortality and there is also growing evidence of cardiometabolic disturbances early in schizophrenic disease [20, 24, 25]. People with schizophrenia may also receive sub-optimal support for metabolic conditions, which could worsen cardiovascular disease outcomes [26]. To address this, many strategies have been proposed, such as regular cardiometabolic follow-up of patients treated with APs and promoting lifestyle interventions [27, 28]. It is important to collect real-world data to assess the occurrence of cardiometabolic complications and to determine if the aforementioned strategies are providing an effect.

An important step to identifying unmet needs and treatment gaps, and to subsequently provide guidance on improving management and outcomes for patients with schizophrenia, is to understand treatment patterns and outcomes in routine clinical practice. We conducted a review of data from the French National Health Data System (Système National des Données de Santé; SNDS) to study pharmaceutical treatment of schizophrenia over a period of 6 years in real-world practice. The SNDS is composed of several databases that collect and collate homogenous information on diagnoses, medical claims, and cause of death for the majority of the population in France. The objectives of this analysis were to describe AP prescription patterns, healthcare utilization, metabolic disturbances and mortality in patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This was an observational study of a cohort of patients with schizophrenia using data from the SNDS between 1st January 2012 and 31st December 2017 (timelines of study summarized in Fig. S1). The study adheres to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [29]. The STROBE checklist is shown in Table S1.

SNDS [30] consolidates data from multiple databases including: the French Health Insurance Database (SNIIRAM) [31]; the Programme for the Medicalisation of Information System (PMSI) [32]; and the Epidemiological Center on the Medical Causes of Death (Center d’épidémiologie sur les causes médicales de décès; CépiDc) [33].

SNIIRAM is a computerized system that collates individual anonymized data regarding all reimbursements for healthcare costs issued to members of one of the compulsory health insurance schemes, which constitutes approximately 99% of all French residents (~65 million individuals) [34]. It is composed of the Inter-scheme Consumption Data (Données de Consommation Inter-Régimes; DCIR), which records reimbursement and treatment data, and the registry of long-term diseases (LTD; Affection de Longue Durée; ALD), which lists the 30 chronic diseases which are exempt from payment.

PMSI is a French hospital discharge database that facilitates medical-economic analysis of information on the diagnosis and hospitalization of patients. PMSI is divided into medicine-surgery-obstetrics-dentistry, psychiatry, after care services and home hospital care. Only data from the medicine-surgery-obstetrics and psychiatry were used in this study.

CépiDc, which is a part of the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM), produces annual statistics on the cause of death in French territories (both mainland and overseas, with the exception of the Department of Mayotte, Africa). Data are based on the death certificate, and this information is sent to INSERM, who records the causes of death. At the time of this analysis, CépiDc data were available for 2013–2015 in the SNDS, and so reported data on mortality are limited by data availability within this timescale.

Patients

Eligible patients were identified in a multi-stage selection process (Fig. S2). In the initial selection stage, patients with schizophrenia were identified in the database from 2010 to 2017 (2 years before the dates for the second stage of the selection process to identify additional information on comorbidities and comedications in the period before inclusion in this analysis) based on the criteria of an active long-term disease during the study with an international classification of diseases—10th revision (ICD-10) diagnostic code of F2.X for schizophrenia (and related disorders) (Table S2) and/or at least one hospital stay in the medicine-surgery-obstetric sector with a main diagnosis or related diagnosis indicative of schizophrenia, and/or at least one hospital stay with a main diagnosis or associated diagnosis indicative of schizophrenia in psychiatry (classified as part-time, full-time or outpatient status).

In the second stage, in which AP users were identified, patients who had at least 3 deliveries (on different dates) of Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical class N05A AP agents (except lithium) between 2012 and 2017 were included (Table S3). Key exclusion criteria are detailed in Fig. S2.

Study endpoints

The co-study endpoints measured prescription patterns, healthcare utilization, metabolic disturbances and mortality in patients with schizophrenia in France. Other endpoints such as the impact of switching from oral APs to LAIs will be reported elsewhere.

Data extraction

Sociodemographic data

Data extracted from SNDS included patient characteristics on the index date, including age group (18–34 years, 35–49 years or ≥50 years [age categories were selected based on previously published data from the QUALIFY study [35] and lack of evidence in elderly patients]), sex and supplementary French Universal Health Cover (Couverture Maladie Universelle Complémentaire). The supplementary French Universal Health Cover is a complementary social security program concerning healthcare for patients whose income is below a set amount [36] and is awarded to people who are not covered under the more general Social Security Insurance (SHI; assurance maladie) system [37]. Receipt of supplementary French Universal Health Cover is a proxy for individuals with very low economic status [38,39,40].

Prescription patterns

AP treatments between 2012 and 2017, including details of the specific AP delivered, exposure and persistence, were collated according to the following subgroups: all APs, oral APs, first-generation LAIs and second-generation LAIs (Table S2). The measure of AP exposure was started as soon as an AP was reimbursed in the SNDS database. An AP exposure period was defined by a succession of AP deliveries, the delay between two deliveries of which does not mark an interruption, a stop or a treatment switch. Persistence to AP treatments was estimated by survival method in patients from exposure periods. AP persistence was defined as the time between starting and discontinuing an AP treatment without any gaps in deliveries. AP persistence is presented as median duration of exposure and as percentage of patients still exposed at 6, 12 and 24 months. The delivery of antidepressants, anxiolytics, anticonvulsants and opiate substitutes were also collated. Treatment patterns of different classes of APs (oral, first- and second-generation) were also assessed over time.

Healthcare utilization

Data were collected on healthcare utilization between 2012 and 2017, including psychiatric hospitalizations (part-time and full-time), related outpatient procedures (i.e., admission to, and care in, mental health outpatient center, part-time therapy center or other care settings), medical consultations with a psychiatrist, general practitioner or other specialists.

Metabolic disturbances

Comorbidities including dyslipidemia, diabetes and hypertensive disease were collated at inclusion and during the entire monitoring period. Comorbidities were identified at index date using algorithms including chronic disease status of patients (Affection de Longue Durée) (Table S3), specific drug dispensations used as proxy (Table S3), and details of hospitalizations for specific conditions. Biological metabolic monitoring procedures of lipid balance, glucose levels, urine tests and blood counts were collated. Cardiovascular medication deliveries were collated (Table S3).

Mortality

For every death, ICD-10 code, sex, date of birth, date of death, and cause of death were recorded on the certificate. If the information on the death certificate was ambiguous, the clinician could state more than one cause of death.

Statistical analysis

No formal sample size estimation was necessary, but with approximately 86% of the adult French population included in the SNDS, a sample size of between 400,000 and 450,000 schizophrenia patients was expected. Based on the premise that summarizing data without drawing probability-based inferences is a key aspect of observational study objectives [41, 42], descriptive statistics were initially used to describe demographic and clinical characteristics, prescribing patterns, mortality rates and healthcare resource utilization, with results presented as means (standard deviation [SD]) and medians (95% confidence interval [CI]) for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. AP persistence was assessed using log-rank methods, according to sex, age group and specific AP delivery.

The standardized mortality ratio was estimated as the ratio of deaths observed in the study population to those expected based on the mortality rates of the French population. Age- and sex-specific death rates per 1000 inhabitants in the French general population were obtained from national statistical data (INSEE) [43]. Age- and sex-standardized mortality rates were adjusted for differences in the age distribution of the population by applying the observed age- and sex-specific mortality rates for the study population to the French population distribution. Analyses were performed using the software SAS® Enterprise Guide v7.4 (SAS Institute North Carolina, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

From the SNDS, 585,718 patients were identified who had at least one diagnosis of schizophrenia during the period 2010–2017. Of these, 585,458 (99.96%) patients had at least three deliveries of an AP, identified between 2012 and 2017. 456,003 of these patients were eligible for the current analysis because they were enrolled in the régime général (RG) or a local mutual association (section locale mutualiste (SLM)), and had validated sociodemographic data on the index date (Fig. S2).

There were slightly more men (n = 244,984; 53.7%) than women (211,019; 46.3%) in the sample and those ≥50 years of age were the largest age category (Table 1). Almost 1 in 5 patients with schizophrenia were of lower socio-economic status (i.e., beneficiaries of supplementary French Universal Health Cover [Couverture Maladie Universelle Complémentaire]) and this was most pronounced in younger age groups with almost 1 in 3 receiving supplementary French Universal Health Cover (Table 1).

Prescription patterns

Patients were followed-up for a mean (SD) of 61 (18) months and, during this period, 96% of patients received oral APs, 17.5% first-generation LAIs, and 16.1% second-generation LAIs (Table 1). Mean (SD) exposure to APs was 38.7 (23.2) months over the entire study period. Women received LAIs less frequently than men, and younger patients received second-generation LAIs more frequently than older patients (Table 1). The more frequently prescribed LAIs were haloperidol decanoate (10.7%), risperidone microspheres (9.5%), paliperidone palmitate 1 monthly (9.0%), zuclopenthixol (4.1%) and aripiprazole monohydrate (2.7%) (Table 1).

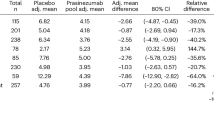

Median persistence of all APs, oral APs, first-generation LAIs and second-generation LAIs was, respectively, 5.4 months (95% CI: 5.4, 5.4), 5.0 months (95% CI: 5.0, 5.0), 3.3 months (95% CI: 3.2, 3.3), and 6.1 months (95% CI: 6.0, 6.1). Persistence rates at 24 months after initiation of treatment were 23.9% for oral APs, 11.5% for first-generation LAIs and 20.8% for second-generation LAIs. Persistence rates at 24 months were slightly higher for men than women for oral APs (25.1% and 22.4%, respectively), first-generation LAIs (11.8% and 11.1%, respectively), and second-generation LAIs (21.2% and 20.0%, respectively). The youngest age group (18–34 years of age) had the lowest persistence rate with all classes of APs (19.9%, 9.3% and 17.8% for oral APs, first-generation LAIs and second-generation LAIs, respectively) compared with the 35–49 years or ≥50 years age groups (26.1%, 12.4% and 22.8%, and 24.3%, 11.6% and 23.0%, respectively). Generally, there was a trend suggesting that second-generation LAIs were gradually increasing in use between 2012 and 2017 while first-generation LAIs were decreasing (Fig. 1).

Among other psychotropic drugs, 62.1% of the patients had at least one delivery of anxiolytics, 45.7% antidepressants and 28.5% anticonvulsants during the study period. Women were more frequently administered these treatments than men: anxiolytics were administered in 66.9% and 58.1%, antidepressants in 52.6% and 39.8%, and mood stabilizers in 30.2% and 27.0%, respectively. There were also differences in the frequency of these treatments according to age group, with a general trend towards an increase in the numbers of patients requiring treatment with age.

Healthcare resource utilization

During the time-period of this study, 52.4% of patients with schizophrenia were hospitalized in psychiatric departments (Table 1); 49.2% were hospitalized full-time and 16.8% were hospitalized part-time for psychiatric-related issues. A total of 229,951 (50.4%) patients were hospitalized in medicine-surgery-obstetrics departments. Less than 50% of patients received treatment from an outpatient psychiatrist. There were no gender differences in healthcare resource utilization (Table 1).

Metabolic disturbances

Overall, 16.2% of patients were diagnosed with dyslipidemia, 9.4% with diabetes, 3.5% with hypertension (Table 1). These rates were higher in women than in men (Table 1). Likewise, the use of cardiovascular medications was more frequent in women than in men (Table 1). Over the course of the study, blood glucose levels were monitored on a median of four occasions, but lipids were measured on a median of one occasion only.

Mortality

Follow-up data between 2013 and 2015 from CépiDc were available for 438,024 patients, where 16,652 deaths were reported (4741, 5582 and 6329 occurred in 2013, 2014 and 2015, respectively). The standardized mortality rate per 1000 patients in 2013, 2014 and 2015, when compared with the general French population, was 27.0 versus 8.1, 30.9 versus 8.5 and 33.7 versus 9.0, respectively. The ratio of mortality rates was similar across the 3 years (3.3 in 2013; 3.6 in 2014 and 3.7 in 2015). The main causes of death were cancer (20.2%) and cardiovascular disease (17.2%; Table 2). Suicide was responsible for 5.9% of all deaths and mental and behavioral disorders for 9.1% (Table 2). The proportion of patients committing suicide was 25.4% among 18–34-year-olds, which was the most frequent cause of death in this age group (Table 2).

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, one of the largest and most comprehensive real-world assessments of patients with schizophrenia treated with APs, conducted in a homogeneous national health system over a period of six years, with individuals derived from a broad spectrum of care settings (hospital and outpatient).

Our results suggest that during the studied period, more than half of the patients with schizophrenia were referred to full-time or day-time hospitalization, highlighting how complex this illness is to manage in outpatient settings. Furthermore, over half of the patients were not seen in outpatient psychiatric settings. Strikingly, while almost all patients had at least one contact with a general practitioner in the study period, less than half had contact with a psychiatrist. Schizophrenia spectrum disorders require a specialist follow-up, and these findings may illustrate patients’ reluctance to consult psychiatrists, due to forced hospitalizations and resulting post-traumatic consequences [44]. Measuring and improving patient-reported experience of psychiatric care is needed to increase compliance to psychiatric follow-up [45, 46]. Hospitalization was much more frequent in 18–34-year-old patients, who have more substance addiction-related comorbidities and lower insight into their illness [47]. This population should be targeted as a priority to improve compliance to psychiatric care. This is the aim of developing initiatives and programs targeting first episode psychosis in many countries, including France, which has more than 30 regional early intervention programs in operation or underway for 15–35-year-old patients [48, 49]. These programs also include suicide prevention, which is of note given that suicide represented the primary cause of mortality among 18–34-year-old patients in our study.

The first striking result is the very low AP persistence, but these values should be interpreted with caution. Oral APs and first-generation LAIs were first marketed long before the study period, whereas some of the second-generation LAIs were launched during the study period (2012–2017). Therefore, second-generation LAI persistence may be underestimated due to the recent addition of these drugs to the market. Over the study period, patients taking first-generation LAIs may have been switched to second-generation LAIs, and our results do show a trend for increasing second-generation and decreasing first-generation LAIs. However, consistent with previous studies, second-generation LAIs appear to have better persistence than oral APs [50,51,52]. This study should be replicated in 5 years, when more data for second generation antipsychotics will be available and there will be longer-acting formulations, which are expected to have a better persistence due to reduced injection frequency [53,54,55].

Considering the very high hospitalization rates in the 18–34 year olds (>68%), it remains to be discussed what the optimal LAI prescription rate should be in this population. Second-generation LAI prescriptions are much higher in this younger population (29%), possibly suggesting that prescribers use LAIs to prevent psychiatric hospitalizations specifically in this population. This may also reflect the recommendation to use second-generation LAIs that were published in 2013 (i.e., during the period of this study) [56]. However, most patients refuse LAIs for multiple reasons [57]. Current recommendations also encourage shared-decision making to increase adherence to treatment [57].

This study also reveals that a considerable proportion of patients who are taking APs also get prescribed antidepressant and/or anxiolytic drugs and/or anticonvulsants. This confirms the complexity of the management of schizophrenia, and emphasizes the importance of adequate screening and monitoring of comorbid symptoms [58]. Such prescriptions were observed to be more frequent in women, contrary to results published in a cohort of younger patients with schizophrenia (mean age 32 years; 74% men) [18]. This discrepancy is therefore probably due to greater representation of older women in the present cohort. Given the known association between anxiety or depression and cardiovascular disease [59, 60], the increased rates of these psychiatric conditions in this study are also explained by higher rates of cardiovascular comorbidities among women in our study. There was a high proportion of patients receiving cardiovascular drugs in this population (higher than the French national average of 5.2% of the population receiving pharmacological treatment for diabetes or 12.5% under 60 years of age receiving lipid-lowering drugs in 2019 [61, 62]) and as expected, many comorbidities, especially cardiometabolic conditions, were more frequent in older age-groups and in women. Moreover, cardiometabolic complications appeared early in a proportion of this population; 10% of the 35–49-year-old patients were diagnosed with dyslipidemia and 12% were prescribed cardiovascular drugs. It is also possible that cardiometabolic conditions are underestimated using the SNDS data, and indeed these conditions are generally under-diagnosed in patients with schizophrenia [63]. The rate of dyslipidemia may also be underestimated as patients had lipid assessments a median of only once during the whole study period of 6 years. However, this is in line with the recommendations of the French Drug Safety Agency (ANSM), i.e., one lipid test every 5 years on maintenance [64]. These results suggest that this frequency could potentially be shortened.

Strategies are clearly needed to prevent cardiometabolic dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia, which contributes to high mortality rates and is predictive of relapse [20, 65]. Lifestyle interventions may be effective, but pose a barrier to patients with motivational deficits [66, 67]. As different APs have different effects on weight gain [68,69,70] and metabolic function [71], another strategy to tackle cardiometabolic dysfunction is to seek alternative treatments that lack metabolic adverse events. However, updated international guidelines to help psychiatrists and general practitioners manage metabolic disturbances in schizophrenia are needed.

The higher standardized mortality rates for patients with schizophrenia than for the general population in France is consistent with data from other countries [17, 72, 73]. Schizophrenia was associated with a loss of life expectancy of around 17 years for men and 8 years for women compared with French national data from Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (INSEE) [43]. The finding that cancer and cardiovascular disease were the most frequent causes of death among older patients is in agreement with evidence supporting a significant association between schizophrenia and both cancer and cardiovascular mortality [74]. The same pattern of occurrence has been observed in other countries, including the USA and Sweden [72, 75]. In the current analysis, deaths in patients with schizophrenia were 3.3 to 3.7 times higher than in the general French population [17]. These data further highlight the need to tackle comorbidities among patients with schizophrenia.

Almost 1 in 5 patients in this study were deemed to be of very low socio-economic status, as they required supplementary French Universal Health Cover (compared with 9% of the general population [76]), and this reflects the difficulty experienced by patients in finding employment [77, 78]. This should alert public authorities to the need for implementation of procedures and collective strategies aimed at promoting recovery and healthy attitudes in this population [79]. Such patients are often under-represented in observational studies, which is a strength of the current analysis.

Study limitations are inherent to an observational study design and specific limitations in relation to this analysis include: as the source of the data was a claims database, it is not possible to determine if APs were administered optimally; diagnosis was based on hospital data and therefore some individuals may have been misclassified due to the lack of a hospital-based diagnosis [80]; because long-acting olanzapine injections are reserved for hospital delivery, information on this agent was not included; and similarly, other medications dispensed during a full-time hospital stay were not recorded. Future analyses could also extract more detailed data on the use of mood stabilizers such as lamotrigine, which is recommended when there is an insufficient response to APs. Likewise, the impact of antidepressants on outcomes would be interesting to assess, and because clozapine is frequently prescribed for more severe schizophrenia, then a separate analysis of clozapine use could be useful. Further analyses could also encompass mortality by cancer type in order to examine the potential association between APs and lung cancer attributed to smoking, for example, given the reported differential effects of first- and second-generation APs on smoking behavior [81]. The use of CMU-C as a proxy measure of low socioeconomic status may be considered an indirect approach but has demonstrated utility in studies evaluating the French population [38,39,40]. Other limitations stemming from the retrospective and claims-based design include the potential for missing data and cases that are not enrolled in the French healthcare system. Notably, our identified sample population of 585,718 with at least one diagnosis of schizophrenia and 456,003 of these patients meeting eligibility criteria was slightly larger than planned and likely reflects a higher than estimated prevalence of patients with schizophrenia and/or a greater proportion seeking care within the healthcare system. Nevertheless, our larger sample population falls within the reported range of 400,000 to 600,000 affected by schizophrenia in France [82], thus supporting the validity and sensitivity of our multi-step selection process and providing increased power for both descriptive and inferential interpretation of the obtained results.

Conclusions

These results provide a roadmap of the priorities in the care of schizophrenia for the coming years. APs alone seem to be insufficient to manage schizophrenia in most cases. AP persistence remains low and rates of psychiatric hospitalization high. Women and patients aged >50 years appear particularly vulnerable to depressive/anxiety disorders and metabolic disturbances beginning as early as 35 years of age. Current health authority recommendations for screening lipid disturbances appear insufficient to prevent metabolic disturbances and their consequences, including cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Suicide prevention remains a priority in 18–34-year-old patients.

References

WHO. Schizophrenia 2019 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia.

Marcus SC, Olfson M. Outpatient antipsychotic treatment and inpatient costs of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:173–80.

Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, Locklear J. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:886–91.

Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK. Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:805–11.

Kozma CM, Weiden PJ. Partial compliance with antipsychotics increases mental health hospitalizations in schizophrenic patients: analysis of a national managed care database. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2009;2:31–8.

Vega D, Acosta FJ, Saavedra P. Nonadherence after hospital discharge in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: A six-month naturalistic follow-up study. Compr Psychiatry. 2021;108:152240.

Haas GL, Garratt LS, Sweeney JA. Delay to first antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: impact on symptomatology and clinical course of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:151–9.

Fernandez-Lazaro CI, Garcia-Gonzalez JM, Adams DP, Fernandez-Lazaro D, Mielgo-Ayuso J, Caballero-Garcia A, et al. Adherence to treatment and related factors among patients with chronic conditions in primary care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pr. 2019;20:132.

Kvarnstrom K, Westerholm A, Airaksinen M, Liira H. Factors contributing to medication adherence in patients with a chronic condition: a scoping review of qualitative research. Pharmaceutics 2021;13:1100.

Pilon D, Alcusky M, Xiao Y, Thompson-Leduc P, Lafeuille MH, Lefebvre P, et al. Adherence, persistence, and inpatient utilization among adult schizophrenia patients using once-monthly versus twice-monthly long-acting atypical antipsychotics. J Med Econ. 2018;21:135–43.

Medic G, Higashi K, Littlewood KJ, Diez T, Granstrom O, Kahn RS. Dosing frequency and adherence in chronic psychiatric disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:119–31.

Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:196–201.

Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, Leckband SG, Jeste DV. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892–909.

Kane JM, McEvoy JP, Correll CU, Llorca PM. Controversies surrounding the use of long‑acting injectable antipsychotic medications for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-021-00861-6.

Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, Kane JM, Correll CU. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:387–404.

Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Nitta M, Leucht S, Olfson M, Kane JM, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:603–19.

Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1123–31.

Fond G, Boyer L, Berna F, Godin O, Bulzacka E, Andrianarisoa M, et al. Remission of depression in patients with schizophrenia and comorbid major depressive disorder: results from the FACE-SZ cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:464–70.

Friedrich ME, Winkler D, Konstantinidis A, Huf W, Engel R, Toto S, et al. Cardiovascular adverse reactions during antipsychotic treatment: results of AMSP, a drug surveillance program between 1993 and 2013. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;23:67–75.

Onwordi E, Howes O. Trends in mortality in schizophrenia and their implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138:489–91.

Hoang U, Stewart R, Goldacre MJ. Mortality after hospital discharge for people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: retrospective study of linked English hospital episode statistics, 1999-2006. BMJ 2011;343:d5422.

Correll CU, Solmi M, Croatto G, Schneider LK, Rohani-Montez SC, Fairley L, et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry. 2022;21:248–71.

Spooner C, Afrazi S, de Oliveira Costa J, Harris MF. Demographic and health profiles of people with severe mental illness in general practice in Australia: a cross-sectional study. Aust J Prim Health. 2022;28:408–16.

Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, Donocik JG, Jauhar S, Howes OD. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:261–9.

Pillinger T, D’Ambrosio E, McCutcheon R, Howes OD. Is psychosis a multisystem disorder? A meta-review of central nervous system, immune, cardiometabolic, and endocrine alterations in first-episode psychosis and perspective on potential models. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:776–94.

Kisely S, Campbell LA, Wang Y. Treatment of ischaemic heart disease and stroke in individuals with psychosis under universal healthcare. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:545–50.

Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, Benjamin S, Lyness JM, Mojtabai R, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:868–72.

Fond G, Godin O, Schurhoff F, Berna F, Andre M, Aouizerate B, et al. Confirmations, advances and recommendations for the daily care of schizophrenia based on the French national FACE-SZ cohort. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;101:109927.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1495–9.

CERTARA. The French Healthcare database SNDS: Access, Analysis, and Study Design France2022 [Available from: https://www.certara.com/evidence-access/real-world-evidence/snds/].

Bezin J, Duong M, Lassalle R, Droz C, Pariente A, Blin P, et al. The national healthcare system claims databases in France, SNIIRAM and EGB: Powerful tools for pharmacoepidemiology. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:954–62.

Boudemaghe T, Belhadj I. Data resource profile: The French national uniform hospital discharge data set database (PMSI). Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:392–d.

Inserm. Centre d’épidémiologie sur les causes médicales de décès 2022 [Available from: https://www.cepidc.inserm.fr/].

CERTARA. The French Healthcare database SNDS: Access, Analysis, and Study Design France2022 https://www.certara.com/evidence-access/real-world-evidence/snds/.

Naber D, Hansen K, Forray C, Baker RA, Sapin C, Beillat M, et al. Qualify: a randomized head-to-head study of aripiprazole once-monthly and paliperidone palmitate in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;168:498–504.

Annuaire s. Couverture maladie universelle complementaire. 2015.

Tikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, Wharton GA International health care system profiles. France 2020 [Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/france#:~:text=Enrollment%20in%20France’s%20statutory%20health,charges%20that%20exceed%20covered%20fees].

de Lagasnerie G, Aguade AS, Denis P, Fagot-Campagna A, Gastaldi-Menager C. The economic burden of diabetes to French national health insurance: a new cost-of-illness method based on a combined medicalized and incremental approach. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19:189–201.

Taha MK, Weil-Olivier C, Bouee S, Emery C, Nachbaur G, Pribil C, et al. Risk factors for invasive meningococcal disease: a retrospective analysis of the French national public health insurance database. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:1858–66.

Chan Chee C, Chin F, Ha C, Beltzer N, Bonaldi C. Use of medical administrative data for the surveillance of psychotic disorders in France. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:386.

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies. Perspect Clin Res. 2019;10:34–6.

Kaliyadan F, Kulkarni V. Types of variables, descriptive statistics, and sample size. Indian Dermatol Online J 2019;10:82–6.

INSEE. Estimations de population et statistiques de l’etat civil. 2018.

Compton MT, Rudisch BE, Craw J, Thompson T, Owens DA. Predictors of missed first appointments at community mental health centers after psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:531–7.

Fernandes S, Fond G, Zendjidjian X, Michel P, Baumstarck K, Lancon C, et al. The Patient-Reported Experience Measure for Improving qUality of care in Mental health (PREMIUM) project in France: study protocol for the development and implementation strategy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:165–77.

Fernandes S, Fond G, Zendjidjian X, Michel P, Lancon C, Berna F, et al. A conceptual framework to develop a patient-reported experience measure of the quality of mental health care: a qualitative study of the PREMIUM project in France. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2021;9:1885789.

Gerretsen P, Plitman E, Rajji TK, Graff-Guerrero A. The effects of aging on insight into illness in schizophrenia: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:1145–61.

Kane JM, Zhao C, Johnson BR, Baker RA, Eramo A, McQuade RD, et al. Hospitalization rates in patients switched from oral anti-psychotics to aripiprazole once-monthly: final efficacy analysis. J Med Econ. 2015;18:145–54.

Meunier-Cussac S, Gozlan G, Lecardeur L, Duburcq C, Courouve L. T33. Early Intervention of Early Psychosis in France, mapping of programs. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:S125–S6.

Verdoux H, Pambrun E, Tournier M, Bezin J, Pariente A. Risk of discontinuation of antipsychotic long-acting injections vs. oral antipsychotics in real-life prescribing practice: a community-based study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135:429–38.

Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, Stoddard J, Doshi JA. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21:754–68.

Kirson NY, Weiden PJ, Yermakov S, Huang W, Samuelson T, Offord SJ, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of depot versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: synthesizing results across different research designs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:568–75.

El Khoury AC, Patel C, Mavros P, Huang A, Wang L, Bashyal R. Transitioning from once-monthly to once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate among veterans with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:3159–70.

Li G, Keenan A, Daskiran M, Mathews M, Nuamah I, Orman C, et al. Relapse and treatment adherence in patients with schizophrenia switching from paliperidone palmitate once-monthly to three-monthly formulation: a retrospective health claims database analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:2239–48.

Mathews M, Gopal S, Nuamah I, Hargarter L, Savitz AJ, Kim E, et al. Clinical relevance of paliperidone palmitate 3-monthly in treating schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:1365–79.

Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, Guillaume S, Lancrenon S, Samalin L. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340.

Becher S, Holzhuter F, Heres S, Hamann J. Barriers and facilitators of shared decision making in acutely ill inpatients with schizophrenia-Qualitative findings from the intervention group of a randomised-controlled trial. Health Expect. 2021;24:1737–46.

Chakos MH, Glick ID, Miller AL, Hamner MB, Miller DD, Patel JK, et al. Baseline use of concomitant psychotropic medications to treat schizophrenia in the CATIE trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1094–101.

Shao M, Lin X, Jiang D, Tian H, Xu Y, Wang L, et al. Depression and cardiovascular disease: Shared molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Psychiatry Res. 2020;285:112802.

Emdin CA, Odutayo A, Wong CX, Tran J, Hsiao AJ, Hunn BH. Meta-analysis of anxiety as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:511–9.

L’Assurance Maladie. Personnes traitées par hypolipémiants (hors pathologies) en 2019. 2019.

Haute Autorite De Sante. Risque cardiovasculaire global en prévention primaire et secondaire: évaluation et prise en charge en médecine de premier recours. 2020.

Oud MJ, Meyboom-de Jong B. Somatic diseases in patients with schizophrenia in general practice: their prevalence and health care. BMC Fam Pr. 2009;10:32.

Agence Francaise de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé. Suivi cardio-métabolique des patients traités par antipsychotiques. 2010.

Talaslahti T, Alanen HM, Hakko H, Isohanni M, Hakkinen U, Leinonen E. Change in antipsychotic usage pattern and risk of relapse in older patients with schizophrenia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:1305–11.

Rastad C, Martin C, Asenlof P. Barriers, benefits, and strategies for physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1467–79.

Sunhary De Verville PL, Stubbs B, Etchecopar-Etchart D, Godin O, Andrieu-Haller C, Berna F, et al. Recommendations of the Schizophrenia Expert Center network for adequate physical activity in real-world schizophrenia (FACE-SZ). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022;272:1273–82.

Abou-Setta AM, Mousavi SS, Spooner C, Schouten JR, Pasichnyk D, Armijo-Olivo S, et al. First-generation versus second-generation antipsychotics in adults: comparative effectiveness. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville (MD)2012.

Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, Lauriello J, Olfson M, Calloway SM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:1–24.

Remington G. Schizophrenia, antipsychotics, and the metabolic syndrome: is there a silver lining? Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1132–4.

Pillinger T, McCutcheon RA, Vano L, Mizuno Y, Arumuham A, Hindley G, et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:64–77.

Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, Stroup TS. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1172–81.

Oakley P, Kisely S, Baxter A, Harris M, Desoe J, Dziouba A, et al. Increased mortality among people with schizophrenia and other non-affective psychotic disorders in the community: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;102:245–53.

Dragioti E, Radua J, Solmi M, Gosling CJ, Oliver D, Lascialfari F, et al. Impact of mental disorders on clinical outcomes of physical diseases: an umbrella review assessing population attributable fraction and generalized impact fraction. World Psychiatry. 2023;22:86–104.

Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, Alexanderson K, Tanskanen A. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:600–6.

Annuaire statistique. Couverture maladie universelle complementaire. 2015.

Sher L, Kahn RS. Suicide in schizophrenia: an educational overview. Med (Kaunas). 2019;55:361.

INSERM. Schizophrenia 2020 [updated 05032020. Available from: https://www.inserm.fr/dossier/schizophrenie/].

Gardien E, Laval C. The institutionalisation of peer support in France: development of a social role and roll out of public policies. Alter. 2019;13:69–82.

Quantin C, Collin C, Frerot M, Besson J, Cottenet J, Corneloup M, et al. [Study of algorithms to identify schizophrenia in the SNIIRAM database conducted by the REDSIAM network]. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2017;65:S226–S35.

Hamdan HF, Zaini S. Effect of nicotine on schizophrenia and antipsychotic medications: a systematic review. Malays J Psych. 2018;27:15.

Jablensky A. Epidemiology of schizophrenia: the global burden of disease and disability. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;250:274–85.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. and H. Lundbeck A/S. The sponsors were involved in the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing and reviewing of the article, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GF, BF, PN, PML and LB conceived and contributed to the design of this study and the analysis of the data. CC designed the data analysis methodology. CC and SD performed the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and all authors approved the final manuscript. The authors take full responsibility for the content of this paper. Writing support was provided by Martin Gilmour and Elisabeth Meredith of Empowering Strategic Performance (ESP) Ltd, Crowthorne, UK and funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. and H. Lundbeck, in accordance with Good Publication Practice 3 (GPP3) guidance. The authors thank the Caisse Nationale de l’Assurance Maladie (CNAM, Demex team) for SNDS data extraction and provision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

GF has received honoraria and has been a consultant for Lundbeck. BF has been a consultant for Abbvie, Actelion, Allergan, Almirall, Alnylam, Amgen, Astellas, Astrazeneca, Bayer, Biogen, Biopecs, Bioproject, Biotronik, BMS, Boehringer, Celgene, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ethypharm, Forestlab, Genevrier, Genzyme, Gilead, Grünenthal, GSK, Guerbet, HRA, IDM Pharma, Idorsia, IMS, Indivior, IQVIA, JNJ, Kephren, Lafon, Leo, Lilly, Lundbeck, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Novonordisk, Otsuka, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabre, Recordati, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Stallergene, Takeda, UCB, ViiV, and Wellmera. PN has received honoraria and has been an advisor to Lundbeck and Otsuka. CC and SD are employees of IQVIA, a contract research agency responsible for the operational management of the study, funded by Lundbeck. MR and IDC are full-time employees of H. Lundbeck A/S. IT is a full-time employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. PML has received personal fees from Janssen, Eisai, Ethypharm, Neuraxpharm, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Sanofi, support for meetings from Eisai, Lundbeck and Ethypharm, and fees for advisory boards from Janssen, Eisai, Ethypharm, Lundbeck, MSD, Neuraxpharm, Otsuka, Roche and Sanofi. LB has received honoraria and has been a consultant for Lundbeck.

Ethics approval

This study was submitted to the Institut National des Données de Santé (INDS) in November 2018, which was later replaced by the French Health Data Hub. In January 2019, a favorable opinion was obtained from CEREES (Scientific Committee for Research, Studies and Evaluation in Public Health; later replaced by CESREES [Ethical and Scientific Committee for Research, Studies and Evaluation in Public Health]). The study was approved by the French data protection agency (CNIL) in February 2019 (registration number: 919034; authorization number: DR-2019–065). No informed consent is required for accessing SNDS data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fond, G., Falissard, B., Nuss, P. et al. How can we improve the care of patients with schizophrenia in the real-world? A population-based cohort study of 456,003 patients. Mol Psychiatry 28, 5328–5336 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02154-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02154-4

This article is cited by

-

Evidence-based clinical care and policy making for schizophrenia

Nature Reviews Neurology (2023)